Published online Jan 6, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i1.107

Peer-review started: October 27, 2023

First decision: November 21, 2023

Revised: November 30, 2023

Accepted: December 15, 2023

Article in press: December 15, 2023

Published online: January 6, 2024

Processing time: 67 Days and 4.4 Hours

Frailty is a common condition in elderly patients who receive percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). However, how frailty affects clinical outcomes in this group is unclear.

To assess the link between frailty and the outcomes, such as in-hospital complications, post-procedural complications, and mortality, in elderly patients post-PCI.

The PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science databases were screened for publications up to August 2023. The primary outcomes assessed were in-hospital and all-cause mortality, major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs), and major bleeding. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale was used for quality assessment.

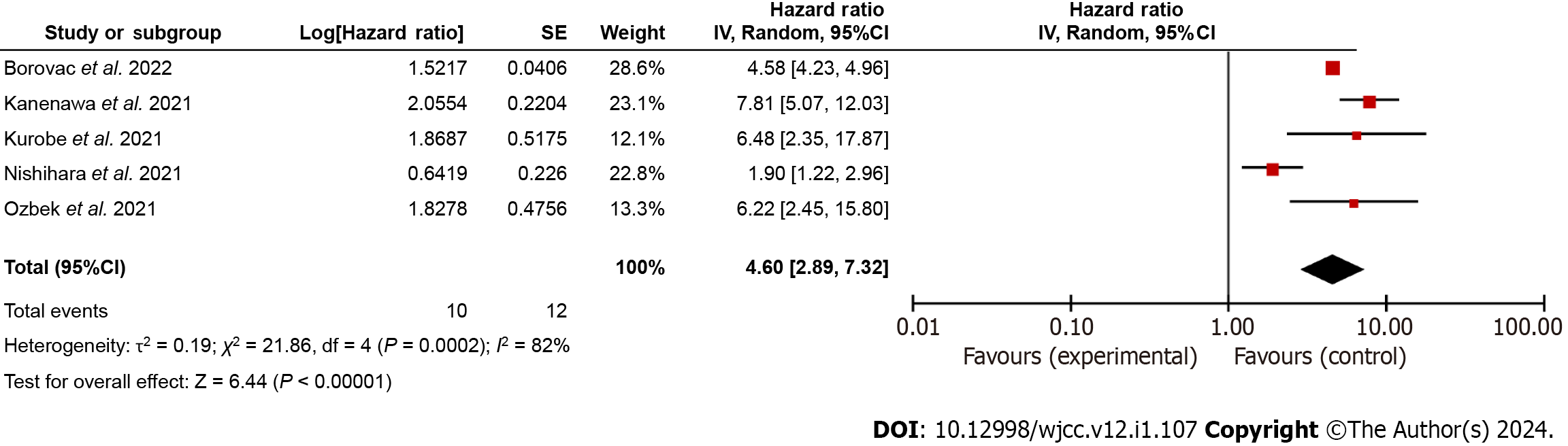

Twenty-one studies with 739693 elderly patients undergoing PCI were included. Frailty was consistently associated with adverse outcomes. Frail patients had significantly higher risks of in-hospital mortality [risk ratio: 3.45, 95% confidence interval (95%CI): 1.90-6.25], all-cause mortality [hazard ratio (HR): 2.08, 95%CI: 1.78-2.43], MACEs (HR: 2.92, 95%CI: 1.85-4.60), and major bleeding (HR: 4.60, 95%CI: 2.89-7.32) compared to non-frail patients.

Frailty is a pivotal determinant in the prediction of risk of mortality, development of MACEs, and major bleeding in elderly individuals undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention.

Core Tip: This comprehensive meta-analysis elucidates the significant impact of frailty on outcomes in elderly patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The study underscores the consistent association between frailty and heightened risks of in-hospital mortality, all-cause mortality, major adverse cardiovascular events, and major bleeding. The convergence of results across diverse study designs, patient populations, and methodological approaches underscores the robustness of these findings. Recognizing frailty as a potent predictor allows for tailored care plans, emphasizing the need for standardized frailty assessment in the pre-PCI evaluation of elderly patients.

- Citation: Wang SS, Liu WH. Impact of frailty on outcomes of elderly patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(1): 107-118

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i1/107.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i1.107

Gradual aging of the world population presents a significant challenge to healthcare systems globally[1]. Prolonged life expectancy correlates with an increased prevalence of cardiovascular diseases, which, in turn, requires complex interventions to effectively manage these conditions[2]. Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is an essential modality in contemporary cardiovascular care, especially in elderly patients, who often present with complex comorbidities[3,4].

Frailty is an important factor that impacts the outcomes of elderly patients undergoing PCI. It is characterized by diminished physiological reserves, reduced functional capacity, and elevated susceptibility to stressors[5-7]. Numerous studies show that frailty is a crucial determinant of healthcare outcomes in the elderly and has a profound influence on morbidity, mortality, and healthcare resource utilization[8,9].

The precise impact of frailty on post-PCI outcomes in the elderly remains a subject of ongoing scientific inquiry and discourse. Understanding the exact association between frailty and procedural outcomes, post-procedural complications, and long-term prognoses in this population is imperative for optimizing patient care and resource allocation[10,11].

This study aimed to assess the link between frailty and outcomes, such as in-hospital complications, post-procedural complications, and mortality, in elderly patients post-PCI.

The study was done per PRISMA guidelines[12].

The PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Library (CENTRAL), and Web of Science databases were searched for publications up to August 31, 2023. The search strategy was designed to identify studies exploring the link between frailty and outcomes in elderly PCI patients.

The study was registered with PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42023446018).

We combined appropriate Medical Subject Headings terms and keywords, including "frailty", "elderly", "percutaneous coronary intervention", and associated synonyms. Only studies in English were considered (Table 1).

| Database | Search string | No. of records |

| PubMed/MEDLINE | ("Frailty"[MeSH] OR "Frail Elderly"[MeSH] OR "Frailty, Psychological"[MeSH] OR "Physical Frailty"[MeSH] OR "Frailty Phenotype"[MeSH] OR "Frailty Scale"[MeSH] OR "Clinical Frailty Scale"[MeSH] OR "Frailty Index"[MeSH] OR "Fried Frailty Criteria" OR "Frailty assessment" OR "Frailty evaluation") AND ("Aged"[MeSH] OR "Elderly"[MeSH] OR "Geriatric"[MeSH] OR "Older Adults" OR "Seniors" OR "Aging" OR "Elderly population") AND ("Percutaneous Coronary Intervention"[MeSH] OR "Coronary Angioplasty"[MeSH] OR "PCI" OR "PTCA" OR "Coronary stenting") | 66 |

| EMBASE | ('frailty'/exp OR 'frail elderly'/exp OR 'psychological frailty'/exp OR 'physical frailty'/exp OR 'frailty phenotype'/exp OR 'frailty scale'/exp OR 'clinical frailty scale'/exp OR 'frailty index'/exp OR 'fried frailty criteria' OR 'frailty assessment' OR 'frailty evaluation') AND ('aged'/exp OR 'elderly'/exp OR 'geriatric'/exp OR 'older adults' OR 'seniors' OR 'aging' OR 'elderly population') AND ('percutaneous coronary intervention'/exp OR 'coronary angioplasty'/exp OR 'PCI' OR 'PTCA' OR 'coronary stenting') AND ('human'/exp AND 'english'/exp) | 158 |

| Cochrane Library (CENTRAL) | ("Frailty"[MeSH] OR "Frail Elderly"[MeSH] OR "Frailty, Psychological"[MeSH] OR "Physical Frailty"[MeSH] OR "Frailty Phenotype"[MeSH] OR "Frailty Scale"[MeSH] OR "Clinical Frailty Scale"[MeSH] OR "Frailty Index"[MeSH] OR "Fried Frailty Criteria" OR "Frailty assessment" OR "Frailty evaluation") AND ("Aged"[MeSH] OR "Elderly"[MeSH] OR "Geriatric"[MeSH] OR "Older Adults" OR "Seniors" OR "Aging" OR "Elderly population") AND ("Percutaneous Coronary Intervention"[MeSH] OR "Coronary Angioplasty"[MeSH] OR "PCI" OR "PTCA" OR "Coronary stenting") | 104 |

| Web of Science | TS=("frailty" OR "frail elderly" OR "physical frailty" OR "frailty phenotype" OR "clinical frailty scale" OR "fried frailty criteria" OR "frailty assessment" OR "frailty evaluation") AND TS=("aged" OR "elderly" OR "geriatric" OR "older adults" OR "seniors" OR "aging" OR "elderly population") AND TS=("percutaneous coronary intervention" OR "coronary angioplasty" OR "PCI" OR "PTCA" OR "coronary stenting") | 111 |

Additionally, a manual search was done, and the bibliography of the eligible studies was also thoroughly screened for any missed citations. No restrictions or filters were applied during the search.

Two authors screened titles and abstracts of identified articles independently for eligibility. Disputes were resolved by discussion. Full-texts of studies selected at the first stage were then assessed for eligibility.

Study design: Randomized controlled trials and cohort, case-control, and observational studies.

Population: Studies involving elderly coronary artery disease patients 65 years and older who underwent PCI.

Exposure variable: Frailty status was assessed using validated tools or criteria, such as the Fried Frailty Phenotype, Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS), or other recognized measures.

Outcome measures: Studies reporting on relevant clinical outcomes, including but not limited to procedural success rates, post-procedural complications (e.g., bleeding and vascular complications), in hospital and all-cause mortality, and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs).

Studies with insufficient data or outcomes that are not pertinent to the research question were excluded. Studies with a sample size of fewer than 30 participants and those with participants not undergoing PCI were also excluded. Conference abstracts, case reports, series, and blog spots, if found, were not included in this review and regarded as excluded.

A standardized data extraction form included the following information: (1) Study characteristics: Author(s), publication year, study design, and setting; (2) Participant characteristics: Demographics, including age, sex, and comorbidities; (3) Frailty assessment: Details of the frailty assessment tool used and the criteria for categorizing participants as frail or non-frail; (4) PCI details: Information on the type of PCI, procedural details, and any relevant interventions; and (5) Outcome measures: Data on primary and secondary outcomes, including post-procedural complications (e.g., bleeding and vascular complications), in hospital and all-cause mortality, and MACEs.

Study quality assessment was done using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for observational studies.

The qualitative analysis included the summary of the findings of the eligible studies. Quantitative synthesis or meta-analysis was performed if data were deemed suitable and sufficiently homogeneous, using a random-effects model to calculate pooled effect estimates. Risk ratios (RRs) and hazard ratios (HRs) were used for categorical outcomes like mortality, risk of developing MACEs, and major bleeding. The adjusted HRs provided were plotted using a generic inverse variance model to calculate the cumulative estimate. Heterogeneity was measured by the I2 statistic. Subgroup analyses were done based on factors such as the study design, frailty assessment tools, and other relevant variables like age and type of patients undergoing PCI. Publication bias was evaluated using visualization of funnel plots and statistical tests, including Egger's and Begg's tests, if required.

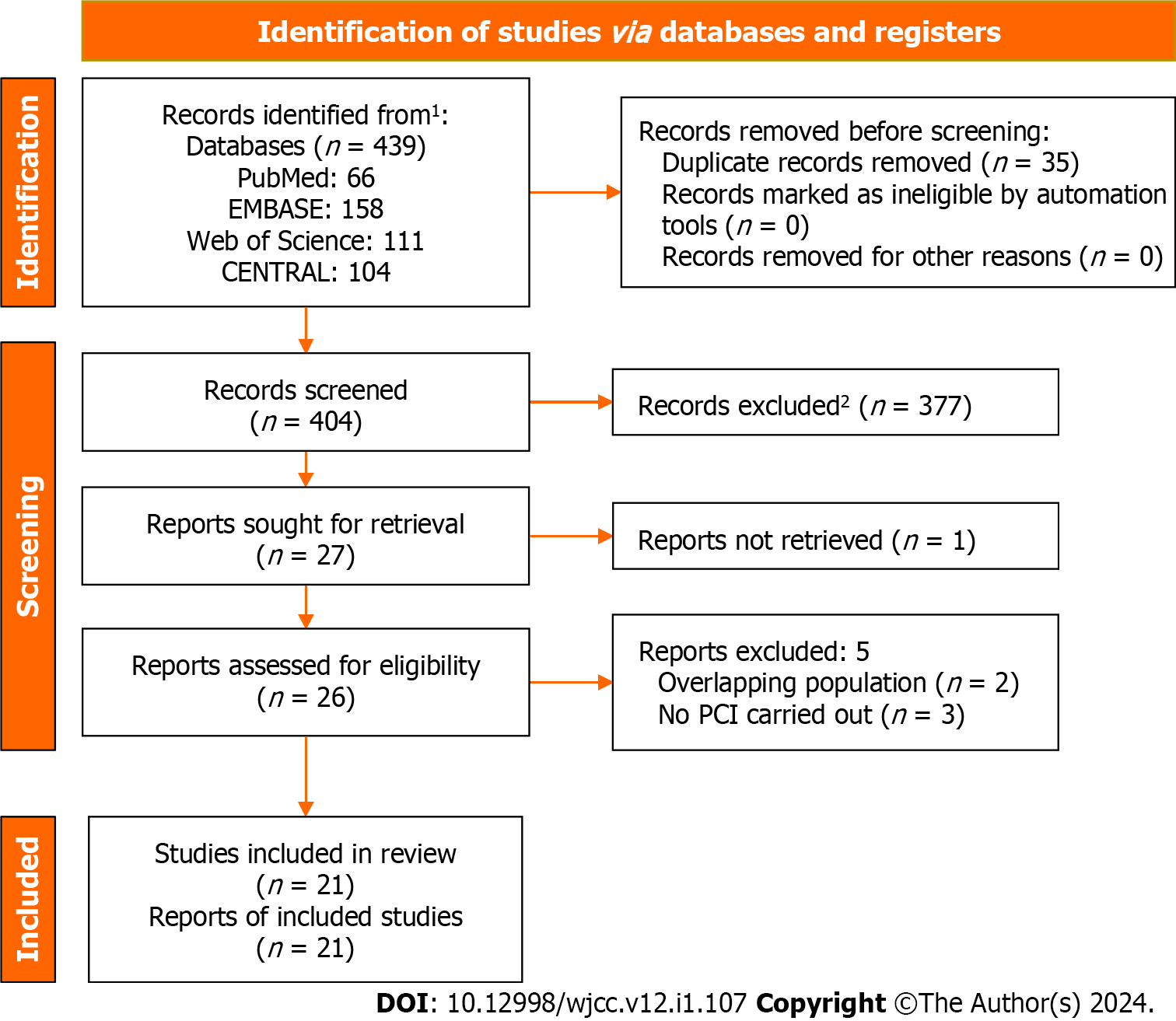

The literature search identified 439 records. Of them, 404 records remained after deduplication and underwent screening of title and abstract. Full-texts of 26 potentially eligible records were thoroughly assessed, and 21 studies[13-33] were deemed eligible for inclusion in the analysis (Figure 1). The details of the included studies are shown in Table 2. All studies were of moderate to high quality (NOS scores of 7-9) (Table 3).

| Ref. | Country | Study design | Frailty criteria | Population | Sample size | Age (yr) | Male (%) | Frail (%) | Follow-up period | Outcomes |

| Shimono et al[13], 2023 | Japan | RC | CFS | Stable coronary artery disease | 239 | 79.5 + 7.5 | 68.40% | 15.90% | 962 d | MACEs, major bleeding, all-cause death, ischaemic events |

| Özbek and Balun[14], 2023 | Turkey | RC | CFS | PCI | 244 | 84.6 + 3.4 | 53.70% | 46.30% | 1 yr | Major bleeding, all-cause death, revascularization, stroke |

| Mangale et al[15], 2023 | India | PC | Clinical frailty scale by Rockwood et al[43], AFN, DFI | STEMI | 402 | 75 + 6 | 64.70% | 32% | 28 d | MACEs |

| Noike et al[16], 2023 | Japan | RC | CFS | Stable angina pectoris | 608 | 77 + 9.2 | 66% | 23.19% | 529 d | MACEs, all-cause death, stroke, cardiac death |

| Heaton et al[17], 2023 | United States | RC | Gilbert’s hospital frailty score | STEMI | 584918 | 63.58 + 13.08 | 69.37% | all | 1 mo | 30-d readmission, mortality |

| Borovac et al[18], 2022 | United States | RC | Hospital Frailty Risk Score (HFRS) | STEMI | 64.6 + 13.7 | 66.80% | 28.40% | NA | Death, cerebrovascular event, and major bleeding | |

| Kanwar et al[19], 2021 | United States | PC | Fried criteria | CAD | 629 | 69 | 69% | 18.60% | 35 mo | All-cause mortality, MACEs |

| Kurobe et al[20], 2021 | Japan | RC | CFS | STEMI | 331 | 77.3 + 10.5 | 57.60% | 22.20% | 35.6 mo | MACEs, all-cause death, stroke |

| Kanenawa et al[21], 2021 | Japan | RC | CFS | PCI | 2439 | 71.9 + 10.1 | 72.70% | 28.30% | 1 yr | All-cause death, MI, stroke, major bleeding |

| Nishihara et al[22], 2021 | Japan | PC | Walking, cognition, and ADL | AMI | 546 | 84.5 (82–88) | 47.80% | 27.80% | 589 d | All-cause mortality, bleeding |

| Kwok et al[23], 2020 | United Kingdom | RC | Validated Hospital Frailty Risk Score | CAD | 73,06,007 | 66.1 + 12.3 | 65.30% | 1836 patients | In hospital | All-cause mortality, MACEs |

| Yoshioka et al[24], 2019 | Japan | RC | CSHA-CFS | STEMI | 273 | 84.6 + 3.8 | 46.20% | 12.50% | 565 d | All-cause mortality |

| Nguyen et al[25], 2019 | Vietman | CS | REFS | PCI | 163 | 73.5 + 8.3 | 60.80% | 41.70% | 30 d | 30-d mortality |

| Damluji et al[26], 2019 | United States | CS | Frail index | AMI | 140089 | > 75 | 46.80% | 9.90% | NA | In-hospital mortality |

| Herman et al[27], 2019 | Netherlands | RC | VMS | STEMI | 206 | 79 + 6.4 | 57.80% | 27.70% | 30 d | All-cause mortality |

| Calvo et al[28], 2019 | Spain | PC | CFS | STEMI | 259 | 82.6 + 6 | 57.90% | 19.70% | In hospital | In-hospital mortality |

| Batty et al[29], 2019 | United Kingdom | PC | Fried criteria | NSTEACS | 280 | 81.0 + 3.5 | 60.00% | 27.50% | 1 yr | MACEs |

| Dodson et al[30], 2018 | United States | CS | FPSS | NSTEMI | 100 | 75.3 + 7.7 | 60.20% | 19.80% | In-hospital | In-hospital bleeding |

| Patel et al[31], 2018 | Australia | CS | Frail index | STEMI | 1275 | > 65 | NA | 52.60% | NA | All-cause death, major bleeding |

| Sujino et al[32], 2015 | Japan | RC | CSHA-CFS | STEMI | 42 | 88.1 + 2.5 | 58.10% | 26.20% | In hospital | In-hospital mortality |

| Murali Krishnan et al[33], 2015 | United Kingdom | PC | CSHA-CFS | CAD | 746 | 62.2 + 7.4 | 70.10% | 10.85% | 1 yr | All-cause mortality |

| Ref. | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Total | |||||

| Representativeness of the exposed cohort | Selection of the nonexposed cohort | Ascertainment of exposure | Demonstration that outcome of interest | Basis of the design or analysis | Assessment of outcome | Follow-up long enough for outcomes | Adequate follow-up | ||

| Shimono et al[13], 2023 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Özbek and Balun[14], 2023 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Mangale et al[15], 2023 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Noike et al[16], 2023 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Heaton et al[17], 2023 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Borovac et al[18], 2022 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Kanwar et al[19], 2021 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Kurobe et al[20], 2021 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Kanenawa et al[21], 2021 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Nishihara et al[22], 2021 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Kwok et al[23], 2020 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Yoshioka et al[24], 2019 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Nguyen et al[25], 2019 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Damluji et al[26], 2019 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Herman et al[27], 2019 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Calvo et al[28], 2019 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Batty et al[29], 2019 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Dodson et al[30], 2018 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Patel et al[31], 2018 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Sujino et al[32], 2015 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Murali Krishnan et al[33], 2015 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

Eleven studies were retrospective cohorts[13,14,16-18,20,21,23,24,27,32], six were prospective cohorts[15,19,22,28,29,33], and four were cross-sectional studies[25,26,30,31]. Studies were conducted between 2015 and 2023, in various countries, and investigated the correlation between frailty and cardiovascular outcomes in different cardiac patient populations. The included studies employed a range of frailty assessment tools, including Gilbert's hospital frailty score, CFS, Fried criteria, Hospital Frailty Risk Score, and other validated measures. The sample sizes varied significantly, ranging from as low as 42 participants to massive cohorts with over 7 million patients. Patient ages also exhibited a considerable diversity, with mean ages ranging from approximately 62 to over 84 years.

In terms of gender distribution among participants, the included studies reported a range from 46.2% to 72.7% of male patients. Frailty prevalence among these populations varied from 9.9% to 66.8%.

The relevant outcomes included a wide array of cardiovascular events, such as MACEs, which encompassed outcomes such as myocardial infarction, stroke, major bleeding, and all-cause mortality. Additionally, revascularization procedures, 30-d readmission rates, and in-hospital mortality were assessed. The follow-up periods ranged from 28 to 962 d.

The presented meta-analysis results demonstrate a significant impact of frailty on various outcomes in the aged population of patients undergoing PCI. The analysis categorized patients into "frail" and "non-frail" groups, and the effect estimates (RR for in-hospital mortality and HR for all-cause mortality, MACEs, and major bleeding) were calculated.

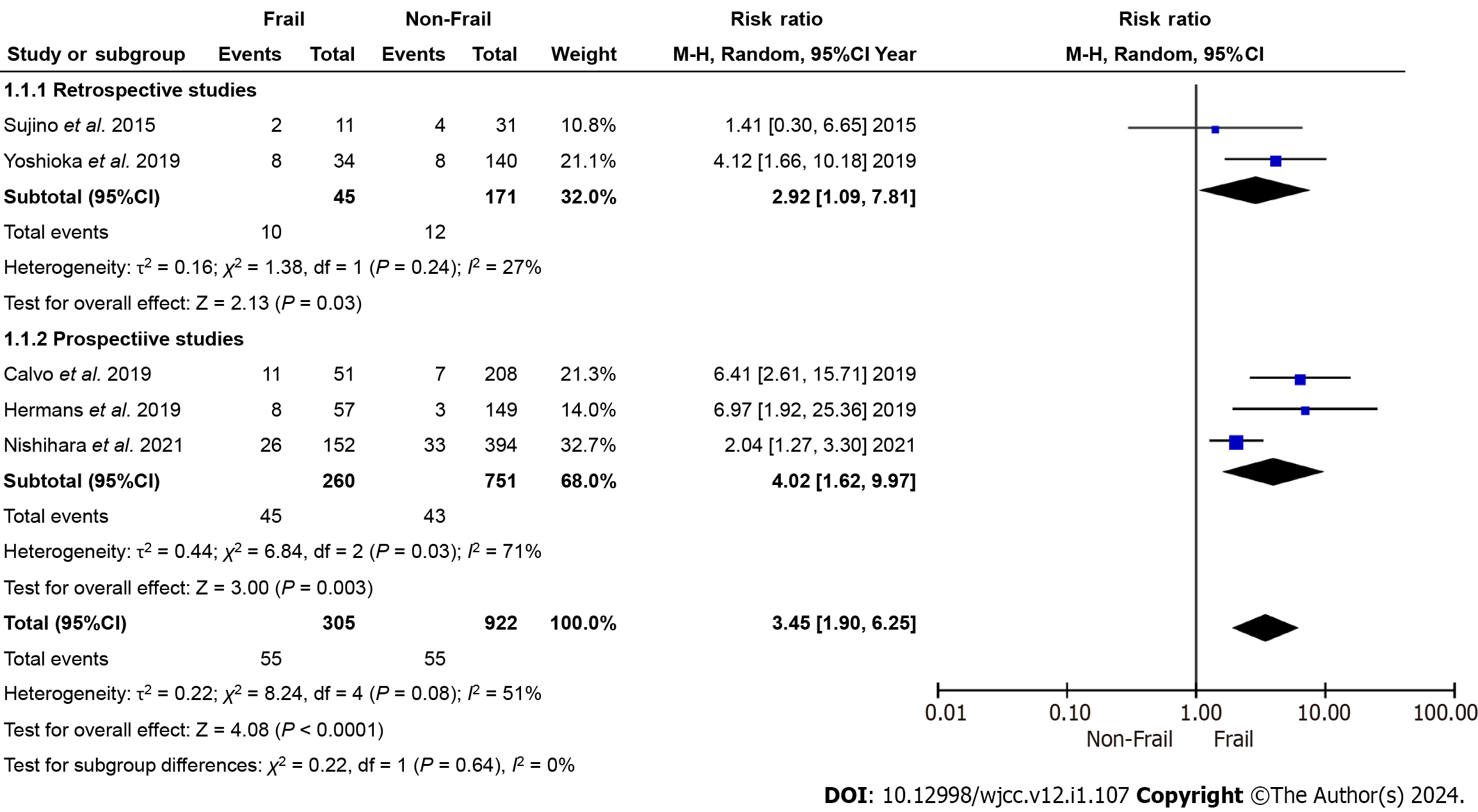

There was a substantial difference in in-hospital mortality between frail and non-frail patients. The overall RR was 3.45 [95% confidence interval (95%CI): 1.90-6.25], showing that frail patients have a significantly higher risk of in-hospital mortality after PCI.

As shown by the subgroup analyses, retrospective studies reported an RR of 2.92 (95%CI: 1.09-7.81), while prospective studies showed an even higher RR of 4.02 (95%CI: 1.62-9.97). These findings underscore the consistency and strength of the relationship between frailty and in-hospital mortality (Figure 2).

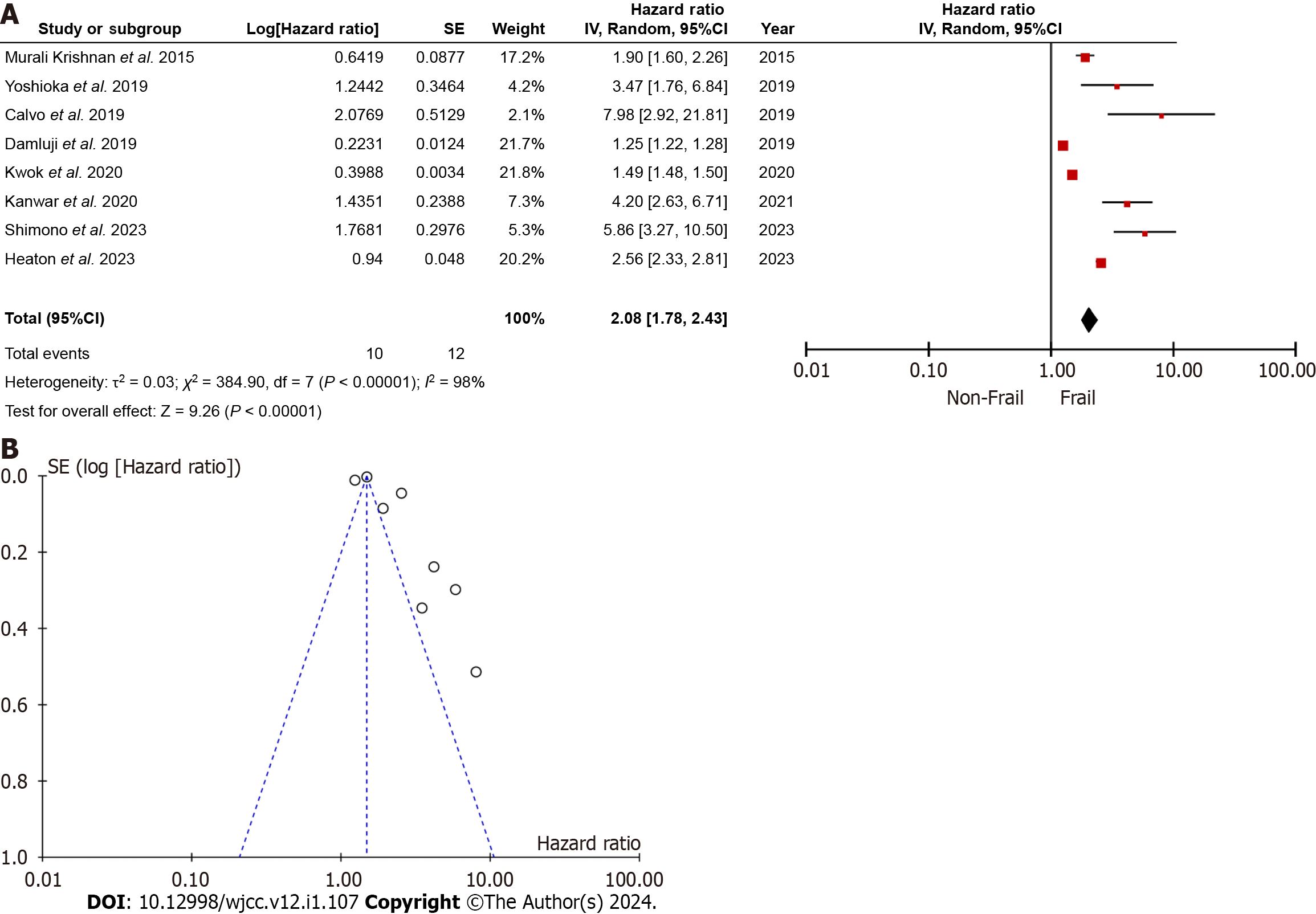

The meta-analysis demonstrated a substantial impact of frailty on all-cause mortality. The HR was 2.08 (95%CI: 1.78-2.43), indicating an over two-fold higher risk of all-cause mortality in frail than in non-frail patients after PCI (Figure 3). The subgroup analysis demonstrated that frailty consistently predicted all-cause mortality across various subgroups, including different study designs, age groups, and indications for PCI (Table 4). The funnel plot showed an evident skewness suggesting publication bias across the studies depicting the estimate of risk for all-cause mortality.

| Criteria | Subgroup | HR (95%CI) | P value | I2 (%) |

| Overall | 2.08 (1.78-2.43) | < 0.0001 | 98 | |

| Study design | Prospective | 2.70 (1.78-2.43) | < 0.0001 | 98 |

| Retrospective | 2.45 (1.51-3.98) | 0.0003 | 90 | |

| Age | < 75 yr | 2.24 (1.15-3.25) | < 0.0001 | 98 |

| > 75 yr | 3.58 (1.29-9.94) | 0.01 | 94 | |

| Frailty scale | CFS | 3.89 (1.88-8.05) | 0.0003 | 86 |

| Others | 1.82 (1.53-2.17) | < 0.0001 | 99 | |

| Patients for PCI | CAD | 1.74 (1.50-2.30) | < 0.0001 | 98 |

| STEMI | 3.48 (2.00-6.03) | < 0.0001 | 64 |

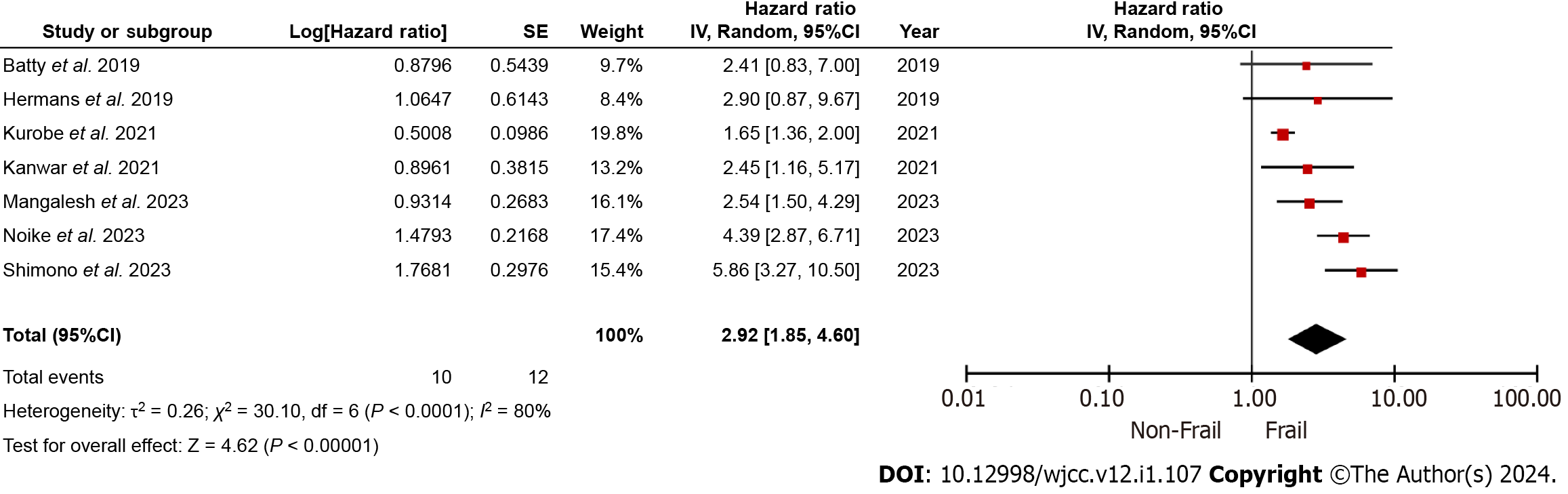

Frailty correlated with a significantly increased risk of MACEs following PCI, with an HR of 2.92 (95%CI: 1.85-4.60) (Figure 4).

Frail patients undergoing PCI were at a considerably higher risk of experiencing major bleeding events. The HR was 4.60 (95%CI: 2.89-7.32), indicating that frailty is a strong predictor of major bleeding complications (Figure 5).

Our results reported that frailty significantly correlates with higher mortality rates in elderly patients undergoing PCI. Frail individuals had a three-fold bigger risk of in-hospital mortality and a two-fold higher risk of all-cause mortality. Frailty was also consistently linked to a nearly three-fold increased risk of MACEs and a two-fold higher risk of major bleeding in elderly PCI patients.

The clinical implications of our findings are significant. Frailty has emerged as a significant factor affecting healthcare outcomes, particularly in cases of invasive procedures in the elderly population. Therefore, identifying frailty in elderly patients who require PCI should prompt a comprehensive evaluation of potential risks and benefits[34,35]. Frailty assessments can aid clinicians in tailoring treatment plans, optimizing post-procedural care, and providing realistic expectations to patients and their families[36,37]. Interventions aimed at mitigating frailty and optimizing overall health may be crucial in improving PCI outcomes in this population. Moreover, frailty assessment can inform shared decision-making processes and guide discussions regarding the suitability of PCI vs alternative treatment strategies.

The subgroup analysis of all-cause mortality in our study demonstrated that frailty consistently predicts all-cause mortality across various subgroups, including different study designs, age groups, and indications for PCI. Our results confirm that frailty assessment is a valuable tool for risk stratification in elderly PCI patients, regardless of study design or age. Moreover, frailty appears to be particularly influential in predicting mortality in older patients and those with acute conditions like ST elevated myocardial infarction[38,39]. However, the substantial heterogeneity within some subgroups suggests the need for further investigation into potential sources of variation in the effect of frailty on mortality in these specific contexts.

Our results are in agreement with previous observations highlighting the adverse impact of frailty on various healthcare outcomes. A meta-analysis by He et al[40] in 2022, with nine studies and a cohort of 2658 patients, showed that the occurrence of frailty was between 12.5% and 27.8% and correlated with higher in-hospital [odds ratio (OR) = 3.59, 95%CI: 2.01-6.42, I2 = 35%], short-term (OR = 6.61, 95%CI: 2.89-15.16, I2 = 0%), as well as long-term mortality (HR = 3.24, 95%CI: 2.04- 5.14, I2 = 70%) of PCI patients. A meta-analysis by Wang et al[41] in 2021 demonstrated an independent positive association of frailty and all-cause mortality (adjusted RR = 2.94, 95%CI: 1.90–4.56, I2 = 56%, P < 0.001) and MACEs (adjusted RR = 2.11, 95%CI: 1.32–3.66, I2 = 0%, P = 0.002). Similarly, a meta-analysis of six studies by Yu et al[42] in 2023 reported higher rates of all-cause mortality (HR= 2.29, 95%CI: 1.65–3.16, P = 0.285), rehospitalization (HR = 2.53, 95%CI: 1.38–4.63), and in-hospital major bleeding (HR = 1.93, 95%CI: 1.29–2.90, P = 0.825) in PCI cohort. Our findings corroborate and extend the understanding of frailty's role in predicting complications and mortality in this specific clinical scenario.

Heterogeneity among the included studies is an essential consideration. We observed variations in frailty assessment tools, study designs, and patient populations. Different frailty assessment methods may yield varying effect estimates, emphasizing the importance of standardized assessment tools in future research. Additionally, subgroup analyses by study design highlighted the robustness of the correlation of frailty with adverse PCI outcomes across different research methodologies.

While we detected certain variability in the quality of evidence across outcomes, it generally ranged from moderate to high. This suggests that further studies are needed to strengthen the certainty of the observed associations.

Our study has several limitations. First, the included studies exhibited substantial heterogeneity in frailty assessment methods, potentially influencing effect estimates. Second, our analysis relied on aggregate data rather than individual patient data, limiting our ability to control for confounders at the individual level. Third, we report a potential publication bias across the studies, as shown in the forest plot for all-cause mortality. Therefore, our results need to be interpreted with caution.

The observed slight differences in ORs between retrospective and prospective studies could be attributed to several factors despite the consistent association between frailty and in-hospital mortality. Retrospective studies rely on historical data and may be subject to inherent biases related to data collection and documentation practices. On the other hand, prospective studies, by their nature, involve real-time data collection and standardized protocols, potentially providing a more accurate reflection of the studied outcomes. Also, retrospective studies may include a broader range of patients over an extended period, leading to potential heterogeneity in patient characteristics, and prospective studies, with their predefined inclusion criteria, might exhibit a more homogeneous patient population.

Future research should focus on standardizing frailty assessment methods and exploring the impact of various interventions to improve frailty in the PCI setting. Longitudinal studies with larger sample sizes and more comprehensive patient data can enhance our understanding of the relationship between frailty and PCI outcomes. Additionally, more studies are needed to establish optimal timing and methods of frailty assessment during the pre-procedural evaluation.

In conclusion, our study provides compelling evidence that frailty is a pivotal determinant of outcomes in elderly individuals undergoing PCI. This underscores the importance of frailty assessment as an integral component of patient management in this population of patients. While our study contributes valuable insights, further research is needed to refine risk stratification, optimize interventions, and improve outcomes for frail elderly patients undergoing PCI.

In exploring the intricate relationship between frailty and outcomes in elderly patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), this study addressed existing gaps in understanding. The relevance of this issue is emphasized given the increasing prevalence of frailty in the aging population.

The motivation behind this research lies in recognizing the clinical significance of frailty in elderly PCI patients and its potential influence on short-term and long-term outcomes. The study aimed to inform clinical practices and enhance patient care by comprehensively exploring the impact of frailty.

The research objectives encompassed a thorough assessment of the association between frailty and key outcomes, including in-hospital mortality, all-cause mortality, major adverse cardiovascular events, and major bleeding. The investigation also sought to identify potential outcome variations based on different study designs, patient characteristics, and indications for PCI. Furthermore, it explored the implications of frailty assessment on personalized care plans and its integration into routine clinical practice.

Comprehensive search strategies were applied across the PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science databases. Statistical methods, including risk ratios and hazard ratios, ensured a robust and standardized approach. Subgroup analyses were conducted to explore variations in outcomes across different study characteristics.

The results of the study established a compelling association between frailty and adverse outcomes in elderly PCI patients. Specific risk increments, such as a three-fold higher risk of in-hospital mortality and a two-fold increase in all-cause mortality, underscored the comprehensive impact of frailty on cardiovascular health. The findings were consistent across retrospective and prospective study designs, affirming the robustness of the association.

In conclusion, the study emphasizes the clinical significance of frailty assessment in the pre-PCI evaluation of elderly patients. It underscores the need for tailored care plans, acknowledging frailty as a potent predictor of adverse events. The research contributes to the existing knowledge by synthesizing key findings and provides a foundation for future research endeavors.

Future research is encouraged to explore interventions targeting frailty and their potential to improve outcomes in elderly PCI patients, advocating for standardized frailty assessment tools and multidisciplinary approaches to enhance the holistic care of this vulnerable patient population.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Teragawa H, Japan S-Editor: Lin C L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Zhao S

| 1. | Christensen K, Doblhammer G, Rau R, Vaupel JW. Ageing populations: the challenges ahead. Lancet. 2009;374:1196-1208. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | Sharifi-Rad J, Rodrigues CF, Sharopov F, Docea AO, Can Karaca A, Sharifi-Rad M, Kahveci Karıncaoglu D, Gülseren G, Şenol E, Demircan E, Taheri Y, Suleria HAR, Özçelik B, Nur Kasapoğlu K, Gültekin-Özgüven M, Daşkaya-Dikmen C, Cho WC, Martins N, Calina D. Diet, Lifestyle and Cardiovascular Diseases: Linking Pathophysiology to Cardioprotective Effects of Natural Bioactive Compounds. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Shanmugasundaram M. Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Elderly Patients. Tex Heart Inst J. 2011;38:398-403. |

| 4. | Guo L, Lv HC, Huang RC. Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Elderly Patients with Coronary Chronic Total Occlusions: Current Evidence and Future Perspectives. Clin Interv Aging. 2020;15:771-781. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Marinus N, Vigorito C, Giallauria F, Haenen L, Jansegers T, Dendale P, Feys P, Meesen R, Timmermans A, Spildooren J, Hansen D. Frailty is highly prevalent in specific cardiovascular diseases and females, but significantly worsens prognosis in all affected patients: A systematic review. Ageing Res Rev. 2021;66:101233. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Singh M, Stewart R, White H. Importance of frailty in patients with cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:1726-1731. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Nguyen DD, Arnold SV. Impact of frailty on disease-specific health status in cardiovascular disease. Heart. 2023;109:977-983. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Xia F, Zhang J, Meng S, Qiu H, Guo F. Association of Frailty With the Risk of Mortality and Resource Utilization in Elderly Patients in Intensive Care Units: A Meta-Analysis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:637446. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | McIsaac DI, Beaulé PE, Bryson GL, Van Walraven C. The impact of frailty on outcomes and healthcare resource usage after total joint arthroplasty: a population-based cohort study. Bone Joint J. 2016;98-B:799-805. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Rowe R, Iqbal J, Murali-Krishnan R, Sultan A, Orme R, Briffa N, Denvir M, Gunn J. Role of frailty assessment in patients undergoing cardiac interventions. Open Heart. 2014;1:e000033. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Rostoft S, van Leeuwen B. Frailty assessment tools and geriatric assessment in older patients with hepatobiliary and pancreatic malignancies. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2021;47:514-518. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Shimono H, Tokushige A, Kanda D, Ohno A, Hayashi M, Fukuyado M, Akao M, Kawasoe M, Arikawa R, Otsuji H, Chaen H, Okui H, Oketani N, Ohishi M. Association of preoperative clinical frailty and clinical outcomes in elderly patients with stable coronary artery disease after percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart Vessels. 2023;38:1205-1217. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Özbek K, Balun A. Effect of frailty on major bleeding in octogenarian patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2023;27:5159-5166. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Mangalesh S, Daniel KV, Dudani S, Joshi A. Combined nutritional and frailty screening improves assessment of short-term prognosis in older adults following percutaneous coronary intervention. Coron Artery Dis. 2023;34:185-194. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Noike R, Amano H, Hirano S, Tsubono M, Kojima Y, Oka Y, Aikawa H, Matsumoto S, Yabe T, Ikeda T. Combined assessment of frailty and nutritional status can be a prognostic indicator after percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart Vessels. 2023;38:332-339. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Heaton J, Singh S, Nanavaty D, Okoh AK, Kesanakurthy S, Tayal R. Impact of frailty on outcomes in acute ST-elevated myocardial infarctions undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;101:773-786. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 18. | Borovac JA, Mohamed MO, Kontopantelis E, Alkhouli M, Alraies MC, Cheng RK, Elgendy IY, Velagapudi P, Paul TK, Van Spall HGC, Mamas MA. Frailty Among Patients With Acute ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction in the United States: The Impact of the Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention on In-Hospital Outcomes. J Invasive Cardiol. 2022;34:E55-E64. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Kanwar A, Roger VL, Lennon RJ, Gharacholou SM, Singh M. Poor quality of life in patients with and without frailty: co-prevalence and prognostic implications in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions and cardiac catheterization. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2021;7:591-600. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 20. | Kurobe M, Uchida Y, Ishii H, Yamashita D, Yonekawa J, Satake A, Makino Y, Hiramatsu T, Mizutani K, Mizutani Y, Ichimiya H, Amano T, Watanabe J, Kanashiro M, Matsubara T, Ichimiya S, Murohara T. Impact of the clinical frailty scale on clinical outcomes and bleeding events in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Heart Vessels. 2021;36:799-808. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 21. | Kanenawa K, Yamaji K, Tashiro H, Morimoto T, Hiromasa T, Hayashi M, Hiramori S, Tomoi Y, Kuramitsu S, Domei T, Hyodo M, Ando K, Kimura T. Frailty and Bleeding After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2021;148:22-29. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 22. | Nishihira K, Yoshioka G, Kuriyama N, Ogata K, Kimura T, Matsuura H, Furugen M, Koiwaya H, Watanabe N, Shibata Y. Impact of frailty on outcomes in elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction who undergo percutaneous coronary intervention. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2021;7:189-197. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 23. | Kwok CS, Achenbach S, Curzen N, Fischman DL, Savage M, Bagur R, Kontopantelis E, Martin GP, Steg PG, Mamas MA. Relation of Frailty to Outcomes in Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2020;21:811-818. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 24. | Yoshioka N, Takagi K, Morishima I, Morita Y, Uemura Y, Inoue Y, Umemoto N, Shibata N, Negishi Y, Yoshida R, Tanaka A, Ishii H, Murohara T; N-Registry Investigators. Influence of Preadmission Frailty on Short- and Mid-Term Prognoses in Octogenarians With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Circ J. 2019;84:109-118. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 25. | Nguyen TV, Le D, Tran KD, Bui KX, Nguyen TN. Frailty in Older Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome in Vietnam. Clin Interv Aging. 2019;14:2213-2222. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 26. | Damluji AA, Huang J, Bandeen-Roche K, Forman DE, Gerstenblith G, Moscucci M, Resar JR, Varadhan R, Walston JD, Segal JB. Frailty Among Older Adults With Acute Myocardial Infarction and Outcomes From Percutaneous Coronary Interventions. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e013686. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 27. | Hermans MPJ, Eindhoven DC, van Winden LAM, de Grooth GJ, Blauw GJ, Muller M, Schalij MJ. Frailty score for elderly patients is associated with short-term clinical outcomes in patients with ST-segment elevated myocardial infarction treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Neth Heart J. 2019;27:127-133. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 28. | Calvo E, Teruel L, Rosenfeld L, Guerrero C, Romero M, Romaguera R, Izquierdo S, Asensio S, Andreu-Periz L, Gómez-Hospital JA, Ariza-Solé A. Frailty in elderly patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2019;18:132-139. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 29. | Batty J, Qiu W, Gu S, Sinclair H, Veerasamy M, Beska B, Neely D, Ford G, Kunadian V; ICON-1 Study Investigators. One-year clinical outcomes in older patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome undergoing coronary angiography: An analysis of the ICON1 study. Int J Cardiol. 2019;274:45-51. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 30. | Dodson JA, Hochman JS, Roe MT, Chen AY, Chaudhry SI, Katz S, Zhong H, Radford MJ, Udell JA, Bagai A, Fonarow GC, Gulati M, Enriquez JR, Garratt KN, Alexander KP. The Association of Frailty With In-Hospital Bleeding Among Older Adults With Acute Myocardial Infarction: Insights From the ACTION Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:2287-2296. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 31. | Patel A, Goodman SG, Yan AT, Alexander KP, Wong CL, Cheema AN, Udell JA, Kaul P, D'Souza M, Hyun K, Adams M, Weaver J, Chew DP, Brieger D, Bagai A. Frailty and Outcomes After Myocardial Infarction: Insights From the CONCORDANCE Registry. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e009859. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 32. | Sujino Y, Tanno J, Nakano S, Funada S, Hosoi Y, Senbonmatsu T, Nishimura S. Impact of hypoalbuminemia, frailty, and body mass index on early prognosis in older patients (≥85 years) with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J Cardiol. 2015;66:263-268. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 33. | Murali-Krishnan R, Iqbal J, Rowe R, Hatem E, Parviz Y, Richardson J, Sultan A, Gunn J. Impact of frailty on outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention: a prospective cohort study. Open Heart. 2015;2:e000294. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 34. | Afilalo J, Alexander KP, Mack MJ, Maurer MS, Green P, Allen LA, Popma JJ, Ferrucci L, Forman DE. Frailty assessment in the cardiovascular care of older adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:747-762. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 35. | Giallauria F, Di Lorenzo A, Venturini E, Pacileo M, D'Andrea A, Garofalo U, De Lucia F, Testa C, Cuomo G, Iannuzzo G, Gentile M, Nugara C, Sarullo FM, Marinus N, Hansen D, Vigorito C. Frailty in Acute and Chronic Coronary Syndrome Patients Entering Cardiac Rehabilitation. J Clin Med. 2021;10. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 36. | Nidadavolu LS, Ehrlich AL, Sieber FE, Oh ES. Preoperative Evaluation of the Frail Patient. Anesth Analg. 2020;130:1493-1503. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 37. | Wilson S, Sutherland E, Razak A, O'Brien M, Ding C, Nguyen T, Rosenkranz P, Sanchez SE. Implementation of a Frailty Assessment and Targeted Care Interventions and Its Association with Reduced Postoperative Complications in Elderly Surgical Patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2021;233:764-775.e1. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 38. | Yoshioka N, Takagi K, Morita Y, Yoshida R, Nagai H, Kanzaki Y, Furui K, Yamauchi R, Komeyama S, Sugiyama H, Tsuboi H, Morishima I. Impact of the clinical frailty scale on mid-term mortality in patients with ST-elevated myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2019;22:192-198. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 39. | Putthapiban P, Vutthikraivit W, Rattanawong P, Sukhumthammarat W, Kanjanahattakij N, Kewcharoen J, Amanullah A. Association of frailty with all-cause mortality and bleeding among elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2020;17:270-278. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 40. | He YY, Chang J, Wang XJ. Frailty as a predictor of all-cause mortality in elderly patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2022;98:104544. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 41. | Wang P, Zhang S, Zhang K, Tian J. Frailty Predicts Poor Prognosis of Patients After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:696153. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 42. | Yu Q, Guo D, Peng J, Wu Q, Yao Y, Ding M, Wang J. Prevalence and adverse outcomes of frailty in older patients with acute myocardial infarction after percutaneous coronary interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Cardiol. 2023;46:5-12. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 43. | Rockwood K, Theou O. Using the Clinical Frailty Scale in Allocating Scarce Health Care Resources. Can Geriatr J. 2020;23:210-215. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |