Published online Mar 16, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i8.1823

Peer-review started: December 13, 2022

First decision: January 17, 2023

Revised: February 1, 2023

Accepted: February 21, 2023

Article in press: February 21, 2023

Published online: March 16, 2023

Processing time: 83 Days and 18.8 Hours

Primary membranous nephrotic syndrome with chylothorax as the first manifestation is an unusual condition. To date, only a few cases have been reported in clinical practice.

The clinical data of a 48-year-old man with primary nephrotic syndrome combined with chylothorax admitted to the Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine of Shaanxi Provincial People's Hospital were retrospec

Primary membranous nephrotic syndrome combined with chylothorax is rare in clinical practice. We report a relevant case to provide case information for clinicians and to improve diagnosis and treatment.

Core Tip: Chylothorax is a white or milky pleural effusion, and primary membranous nephrotic syndrome is a rare cause of chylothorax. This article reports a case of primary membranous nephrotic syndrome combined with chylothorax and summarizes the relevant cases to raise awareness of chylothorax among clinicians.

- Citation: Feng LL, Du J, Wang C, Wang SL. Primary membranous nephrotic syndrome with chylothorax as first presentation: A case report and literature review. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(8): 1823-1829

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i8/1823.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i8.1823

Chylothorax is a white, milky or muddy fluid containing a high level of triglycerides and chylomicron emulsion that is present in the pleural cavity and is rarely seen clinically. It is mainly caused by trauma, malignant tumours, and autoimmune diseases. Adult primary membranous nephrotic syndrome, which is a rare cause of chylothorax, has been poorly reported in the national and international literature, with only isolated cases and no relevant epidemiological reports. Moreover, the related mechanism and clinical characteristics of primary membranous nephrotic syndrome combined with chylothorax are still unclear.

Here, we report a case of primary membranous nephrotic syndrome with chylothorax in an adult and review and summarize the related mechanisms, clinical characteristics, and treatment of primary membranous nephrotic syndrome with chylothorax to help clinicians improve the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of this disease.

A 48-year-old Chinese man presented to the hospital with a complaint of dyspnoea for 12 d.

The patient presented 12 d earlier with dyspnoea after activity, facial oedema, which was prominent in the morning, pitting oedema of both lower limbs that resolved after rest, occasional dry coughing, and no low-grade fever, chills, or night sweats.

The patient was previously healthy and free from any disease. And he denied hospitalizations. There was no history of recent surgery, catheter insertion, trauma, drug or food allergies, or chemical or toxic material exposure.

The patient denied any family history of the condition.

The vital signs were as follows: Body temperature, 36.3 ℃; blood pressure, 140/76 mmHg; heart rate, 70 beats per min; and respiratory rate, 30 breaths per min. The patient was tachypneic. Physical examination showed slightly weakened breath movements on the right side of the chest, with decreased breath sounds on both sides of the chest, but especially on the right side, and no rales or pleural friction sounds were heard. Cardiac and abdominal examinations were unremarkable.

Related pleural effusion tests showed a chyle-like fluid, total pleural effusion cholesterol of 1.0 mmol/L, pleural effusion triglycerides of 2.68 mmol/L, and a positive chyle test. Routine urinalysis showed leukocyturia and tubular proteinuria; liver function showed hypoproteinaemia; blood lipid profile showed total cholesterol of 11.68 mmol/L and triglycerides of 2.22 mmol/L; urine protein quantification showed a urine protein concentration of 8160 mg/L, urine volume of 2.65 L, and total urine protein of 21624 mg/24 h; urinary chyle qualitative testing was positive; erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 68 mm/h; and some of the tumour indicators, namely, glycoantigens CA-125 and CA19-9, were elevated. Autoimmune series, routine haematology, coagulation function, viral hepatitis, rheumatic series, thyroid function, T-cell test for tuberculosis infection, and renal function were normal. Repeated pleural effusion and bronchoalveolar lavage smears did not reveal tuberculosis, or bacterial or fungal infections.

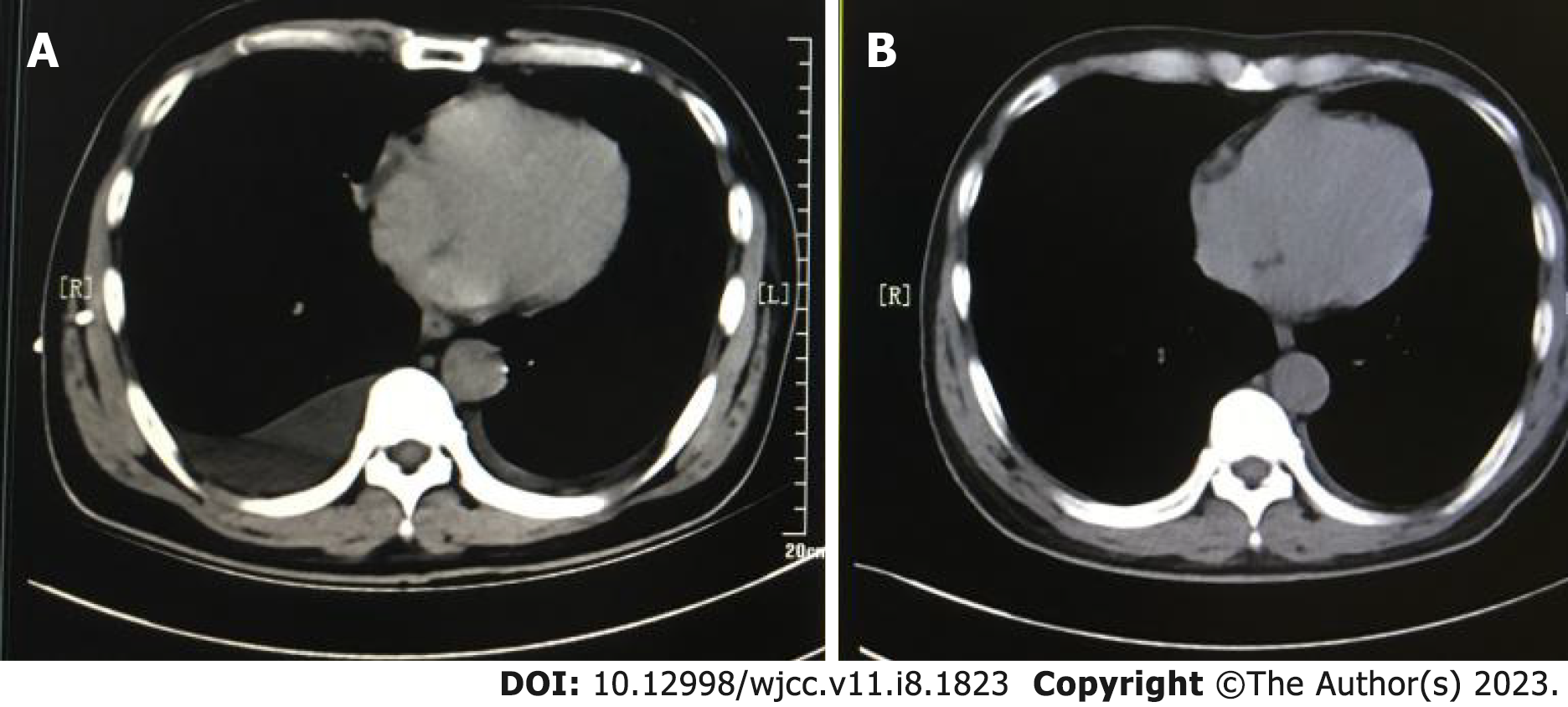

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest showed bilateral pleural effusion (moderate on the right and small on the left) (Figure 1A). Bronchoscopy, cardiac ultrasound, CT of the abdomen and pelvis, and whole-body positron emission tomography/CT were normal.

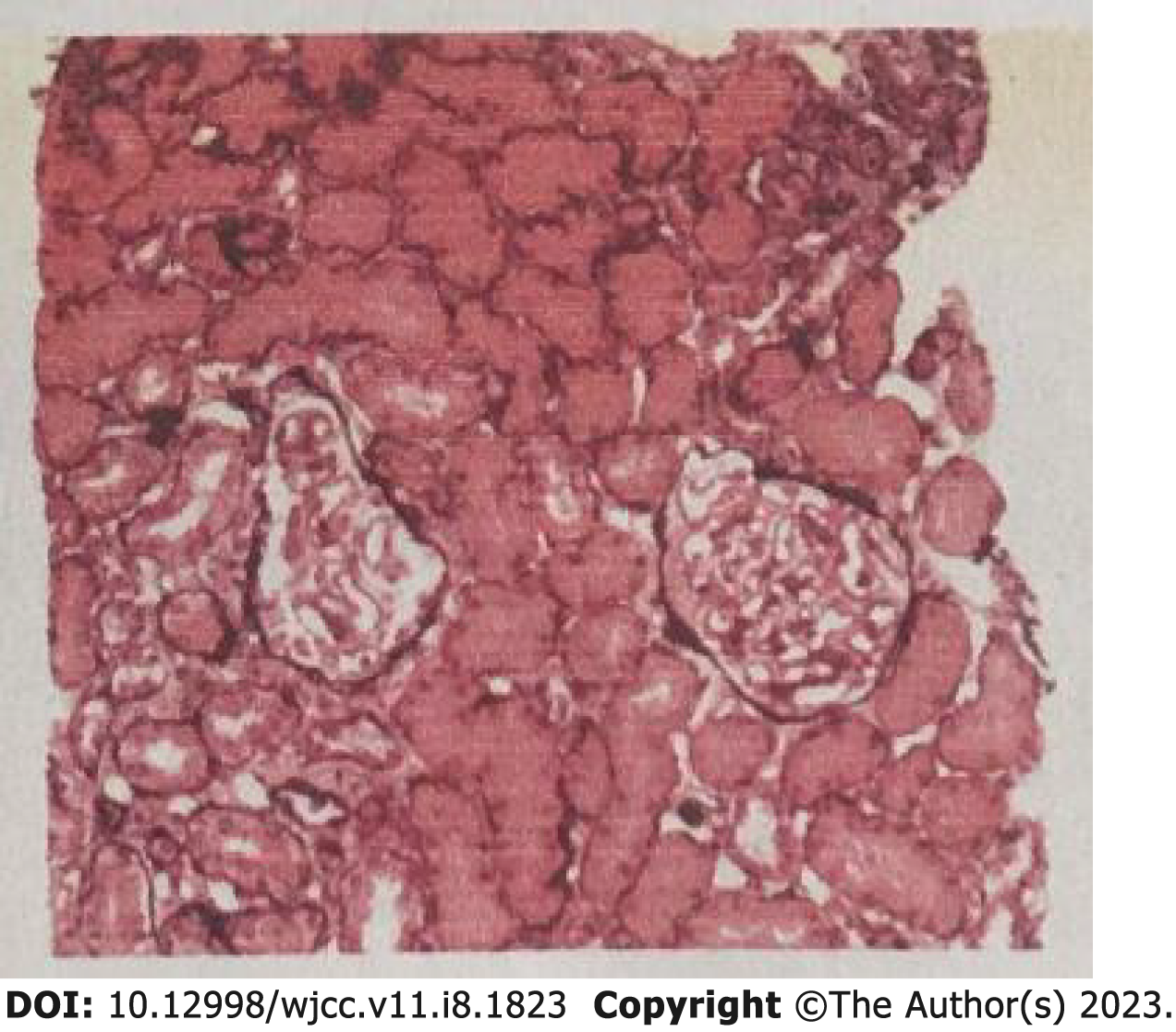

The patient underwent closed thoracic drainage after admission (Figure 2). In combination with the history, symptoms, signs and relevant laboratory tests, the patient was determined to be suffering from nephrotic syndrome after a consultation with nephrologists. To further clarify the diagnosis, a positive anti-phospholipase A2 receptor antibody (PLA2R) was detected (1:320). A percutaneous nephrectomy biopsy was performed under ultrasound guidance, and the postoperative pathology was consistent with stage I membranous nephropathy (Figure 3).

Combined with the patient’s medical history, the final diagnosis was primary membranous nephrotic syndrome with chylothorax and chylous urine.

Approximately 500 mL of fluid was drained per day via a closed chest drainage tube, and the patient was given a low-salt, low-fat, and low-protein diet, diuretic therapy, and other symptomatic supportive treatment. After the diagnosis was confirmed, he was treated with oral methylprednisolone and cyclosporine A.

After 1 wk, the patient's oedema had subsided, the pleural effusion had disappeared, and the dyspnoea had improved significantly (Figure 1B). A review of relevant laboratory tests showed blood total cholesterol of 10.04 mmol/L, blood triglycerides of 3.78 mmol/L, urine protein concentration of 4730 mg/L, and total urine protein of 9460 mg/24 h, and the urinary chyle qualitative test was negative. The patient was discharged in better condition and remains in follow-up.

Membranous nephropathy (MN) is a common pathological type of primary nephrotic syndrome in adults[1]. MN is an autoimmune disease caused by an autoantibody attack against podocyte antigens that results in the production of in situ immune complexes, mediated primarily by anti-PLA2R (85%), antibodies to the thrombospondin type 1 structural domain containing 7A (3%-5%), or other unknown mechanisms (10%)[2]. Most adults (80%) with primary membranous nephropathy present with nephrotic syndrome, with the remainder presenting with nephrotic proteinuria[2].

In contrast, chylothorax is a rare complication of primary nephrotic syndrome first reported in 1989 by Moss Retal[3]. Chylothorax is usually caused by injury to the thoracic duct and chyle leakage from the lymphatic system into the pleural cavity. Most chylothorax-inducing injuries are caused by medical trauma and surgery[4-6]. Apart from those main causes, tuberculous lymphadenitis, autoimmune diseases, malignancies, and congenital ductal abnormalities may also induce chylothorax[7-9].

A literature review was performed through April 2022; the Chinese Biomedical Literature Database, PubMed, and other national and international databases were searched using the term "nephrotic syndrome, chylothorax" without date or language restrictions. All the relevant literature and cross-references were checked to ensure that all eligible cases were included in the statistical analysis. Fourteen foreign papers were reviewed[2,10-22], and the majority of cases were individual case reports[23-30]. Four of the cases were diagnosed with microscopic nephrotic syndrome (3 foreign and 1 domestic); 3 with membranous nephrotic syndrome (3 foreign); 3 with focal segmental glomerulosclerotic nephrotic syndrome (all foreign); 3 with membranoproliferative nephrotic syndrome (2 foreign and 1 domestic); 1 with membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (all domestic); and 9 with undetermined pathology. Most of the patients, of which 10 were children, were admitted with facial and bilateral lower limb oedema; the youngest patient was 2.5 years old and the oldest was 66 years old. There were 15 males and 8 females. Pleural effusion was mostly bilateral, predominantly on the right side and with a smaller amount on the left. Ten of the patients had celiac effusion, and 6 had thrombosis (not available in detail).

The specific pathogenesis of primary nephrotic syndrome complicated by chylothorax remains unclear. An analysis of this case in combination with previous literature reports reveals that the pathogenesis may be related to the following mechanisms. First, nephrotic syndrome leads to hypoproteinaemia and severe systemic tissue oedema, and lymphatic vascular oedema increases the permeability of the intestinal mucosa and lymphatic vessels, causing celiac particle leakage and celiac pleural effusion. Second, severe tissue oedema increases the pressure in the capillaries and lymphatic vessels, leading to the rupture of lymphatic vessels and the leakage of celiac fluid. In addition, it has also been reported that in membranous nephropathy with chylous ascites, negative intrapleural pressure causes celiac ascites to enter the pleural cavity through the diaphragmatic defect. In the case of massive ascites, the intraperitoneal pressure increases, and the peritoneum thins and folds back upwards through the transverse septal fissure to form large vesicles. The continuous increase in pressure in the abdomen causes large vesicles to rupture and chylous ascites to enter the pleural cavity to form chylothorax[11,19,31]. Rathore et al[18] reported a case of chylothorax in an 8-year-old child and found that the hypercoagulable state of the blood in nephrotic syndrome could lead to venous thrombosis (superior vena cava and subclavian vein thrombosis), as it causes impaired lymphatic return and increased pressure in the lymphatic vessels. When the pressure in the lymphatic vessels exceeds the drainage capacity of the thoracic duct, the pleural lymphatic vessels dilate, stagnate, and rupture, resulting in the overflow of lymphatic fluid to form chylothorax. More research is needed to confirm whether there are other mechanisms involved in nephrotic syndrome and chylothorax, and whether they are related to the type of pathology.

Clinically, the diagnosis of primary nephrotic syndrome with chylothorax is based on past medical history, clinical symptoms and signs, and laboratory and imaging tests. The clinical symptoms of primary nephrotic syndrome with chylothorax are atypical. In addition to the manifestations of the primary disease, the symptoms mostly include dyspnoea, shortness of breath, and cough caused by pleural effusion, and the diagnosis is not specific. In contrast, thoracentesis and laboratory tests are often used as the preferred diagnostic methods for chylothorax. Laboratory tests for chylothorax often have the following characteristics for its diagnosis: (1) The fluid is white, milky or cloudy in appearance, and liquid stratification occurs after resting; (2) The fluid is rich in lymphocytes, often polyclonal T-cell populations, and is usually alkaline, with a pH value between 7.4 and 7.8; (3) Thoracic effusion triglyceride levels are specific for the diagnosis of chylothorax. Chylothorax is diagnosed when triglycerides are > 110 mg/dL, cholesterol is < 200 mg/dL and celiac particles are microscopically visible. Thoracic effusion with a triglyceride value < 50 mg/dL usually rules out chylothorax. Triglyceride levels between 55 and 110 mg/dL require lipoprotein electrophoresis analysis to detect chyle particles. In patients who are fasting or malnourished, lipoprotein electrophoresis analysis is recommended even if triglycerides are < 50 mg/dL; and (4) A thoracic effusion-to-serum triglyceride ratio > 1, a thoracic effusion-to-serum cholesterol ratio < 1, and a thoracic effusion triglyceride-to-cholesterol ratio > 1 may also aid in the diagnosis of chylothorax. X-rays, ultrasound, CT, magnetic resonance imaging, lymphography, and nuclear lymphography can also clarify the cause of chylothorax, and if necessary, histopathological biopsy or excision of the positive lesions on imaging may be performed as appropriate.

The treatment of nephrotic syndrome with chylothorax should be individualised and combined, i.e., with active treatment of the primary disease and simultaneous treatment of chylothorax to achieve a faster cure or remission. Therefore, the basic treatment of chylothorax lies in symptomatic supportive treatment.

The patient presented to the Shaanxi Provincial People's Hospital with a complaint of dyspnoea for the preceding 12 d. Laboratory tests suggested hypoproteinaemia, hyperlipidaemia, and massive proteinuria, consistent with nephrotic syndrome. The patient had no history of recent surgery, catheter insertion or trauma, recurrent respiratory infections, or chemical or toxic exposure, and laboratory and imaging tests ruled out chylothorax due to tuberculosis, a fungus, or a tumour. The patient had no history of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug abuse, and secondary membranous nephropathy was excluded. The diagnosis of primary membranous nephropathy syndrome with chylothorax was clear, taking into account the pathological findings of the renal biopsy, the clinical symptoms and signs, all test results, and the effectiveness of various drugs during the course of treatment.

For this patient, we administered conservative symptomatic supportive treatment, reduced cholesterol intake through a low-salt, low-fat and low-protein diet, and increased physical activity to reduce weight. Symptomatic treatment, such as diuresis and albumin supplementation, can relieve tissue oedema and pleural effusion, and growth inhibitors as well as omeprazole can reduce chylous fluid production. In this case, the pleural effusion was significantly reduced after aggressive treatment, and the patient’s shortness of breath was relieved.

Chylothorax is a rare complication of primary nephrotic syndrome, and a systematic differential diagnosis should be made clinically. Furthermore, a pathological biopsy should be performed when the diagnosis is unclear. By reporting this case, we hope that clinicians can improve their understanding of primary nephrotic syndrome and chylothorax, enriching their clinical knowledge, and provide new ideas for future clinical treatment.

| 1. | Ayalon R, Beck LH Jr. Membranous nephropathy: not just a disease for adults. Pediatr Nephrol. 2015;30:31-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Couser WG. Primary Membranous Nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12:983-997. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 548] [Cited by in RCA: 474] [Article Influence: 52.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 3. | Moss R, Hinds S, Fedullo AJ. Chylothorax: a complication of the nephrotic syndrome. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;140:1436-1437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Liu YM, Wei YJ, Lu XQ, Wang YF, Wang P, Liang XH. Catheter-related superior vena cava obstruction: A rare cause of chylothorax in maintenance hemodialysis patients. J Vasc Access. 2022;11297298211073425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ruggiero RP, Caruso G. Chylothorax--a complication of subclavian vein catheterization. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1985;9:750-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zheng XD, Li SC, Lu C, Zhang WM, Hou JB, Shi KF, Zhang P. Safety and efficacy of minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy in 1023 consecutive esophageal cancer patients: a single-center experience. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2022;17:36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kutlu O, Demirbas S, Sakin A. Chylothorax due to tuberculosis lymphadenitis. North Clin Istanb. 2016;3:225-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Takano H, Taoka K, Hayashida H, Tsushima T, Sugimura H, Yamazaki I, Hara H, Mihara M, Yamamoto M, Shimura A, Masamoto Y, Kurokawa M. [Successful treatment of refractory chylothorax associated with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by multidisciplinary care]. Rinsho Ketsueki. 2021;62:1623-1627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tang X, Chen Z, Shen X, Xie T, Wang X, Liu T, Ma X. Refractory thrombocytopenia could be a rare initial presentation of Noonan syndrome in newborn infants: a case report and literature review. BMC Pediatr. 2022;22:142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bonnin Vilaplana M, Pelegrí Santos A, Parra Ordaz O. [Chylotorax and chylose ascites: initial manifestation of a nephrotic syndrome]. Med Clin (Barc). 2006;127:718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chen YC, Kuo MC, Chen HC, Liu MQ, Hwang SJ. Chylous ascites and chylothorax due to the existence of transdiaphragmatic shunting in an adult with nephrotic syndrome. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:1501-1502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cogar BD, Groshong TD, Turpin BK, Guajardo JR. Chylothorax in Henoch-Schonlein purpura: a case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2005;39:563-567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hanna J, Truemper E, Burton E. Superior vena cava thrombosis and chylothorax: relationship in pediatric nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 1997;11:20-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kren L, Rotterova P, Hermanova M, Krenova Z, Sterba J, Dvorak K, Goncharuk V, Wilner GD, McKenna BJ. Chylothorax as a possible diagnostic pitfall: a report of 2 cases with cytologic findings. Acta Cytol. 2005;49:441-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lin SH, Lin YF, Shih YL. An unusual complication of nephrotic syndrome: chylothorax treated with hemodialysis. Nephron. 2001;87:188-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lin WY, Lin GM, Wu CC. Coexistence of non-communicated chylothorax and chylous ascites in nephrotic syndrome. Nephrology (Carlton). 2009;14:700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Poswal L, Dhyani A, Malik P, Ameta P. Bilateral Chylothorax due to Brachiocephalic Vein Thrombosis in Relapsing Nephrotic Syndrome. Indian J Pediatr. 2015;82:1181-1182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Rathore V, Bhattacharya D, Pandey J, Bhatia A, Dawman L, Tiewsoh K. Chylothorax in a Child with Nephrotic Syndrome. Indian J Nephrol. 2020;30:32-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Singh SK, Chauhan A, Swain B. A rare case of nephrotic syndrome with chylothorax. J Family Med Prim Care. 2021;10:3498-3501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Suri D, Gupta N, Morigeri C, Saxena A, Manoj R. Chylopericardial tamponade secondary to superior vena cava thrombosis in a child with nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2009;24:1243-1245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Voudiclari S, Sonikian M, Kallivretakis N, Pani I, Kakavas I, Papageorgiou K. Chylothorax and nephrotic syndrome. Nephron. 1994;68:388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Xu Y, Shi J, Xu S, Cui C. Primary nephrotic syndrome complicated by chylothorax: a case report. Ann Palliat Med. 2022;11:2523-2528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Dong JX. One1 case of nephrotic syndrome with chylothoracic ascites. Journal of Suzhou Medical College. 1995;648. |

| 24. | Fu Q, Fan JF, Zhou N, Chen Z, Liu XR. Childhood nephrotic syndrome and true chylothorax in one case. The Chinese Clinical Journal of Practical Pediatrics. 2020;469-471. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 25. | Li XM, Chen BW. Nnephrotic syndrome and large chylothorax ascites one case. Journal of Rare Diseases. 2003;51-52. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 26. | Wang P, Jun ZJ. One case with chylothoracic water was reported. Chinese and Foreign Medical Treatment. 2008;71. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 27. | Wu LR. Two cases with nephrotic syndrome and chylothorax. Guangdong Medicine. 1994;138-139. |

| 28. | Xu YY. Nephrotic syndrome complicated with chylothorax and ascites. Jiangsu Medicine. 1989;8. |

| 29. | Yang YJ, Zhang SP, Gao ZY. One case of chylous pleural effusion caused by primary nephrotic syndrome. Clinical meta-study. 2007;894. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 30. | Zhou LM, Zhu L, Wang P. Primary nephrotic syndrome complicated with chylothor ax in 1 case. Journal of Medical College of Qingdao University. 2008;98. |

| 31. | Liu X, Xu Y, Wu X, Liu Y, Wu Q, Wu J, Zhang H, Zhou M, Qu J. Soluble Immune-Related Proteins as New Candidate Serum Biomarkers for the Diagnosis and Progression of Lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Front Immunol. 2022;13:844914. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Arunachalam J, India; Ullah K, Pakistan S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Wang LL