Published online Mar 6, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i7.1434

Peer-review started: September 29, 2022

First decision: November 25, 2022

Revised: December 20, 2022

Accepted: February 13, 2023

Article in press: February 13, 2023

Published online: March 6, 2023

Processing time: 154 Days and 7.9 Hours

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has imposed a radical change in daily life and work routine. In this context, health systems have suffered important and serious repercussions in all fields. Among the changes brought about by the state of global health emergency, adjustments to guidelines, priorities, structures, professional teams, and epidemiological data stand out. In light of this, the oncological field has witnessed several changes in the approach to cancer, whether due to delay in diagnosis, screening deficit, personnel shortage or the psychological impact that the pandemic has had on cancer patients. This article focuses on the management of oral carcinoma and the surgical approaches that oral and maxillofacial specialists have had at their disposal during the health emergency. In this period, the oral and maxillofacial surgeons have faced many obstacles. The proximity of maxillofacial structures to the airways, the need of elective and punctual procedures in cancerous lesions, the aggressiveness of head and neck tumors, and the need for important healthcare costs to support such delicate surgeries are examples of some of the challenges imposed for this field. One of the possible surgical 'solutions' to the difficulties in managing surgical cases of oral carcinoma during the pandemic is locoregional flaps, which in the pre-COVID-19 era were less used than free flaps. However, during the health emergency, its use has been widely reassessed. This setback may represent a precedent for opening up new reflections. In the course of a long-term pandemic, a reassessment of the validity of different medical and surgical therapeutic approaches should be considered. Finally, given that the pandemic has high-lighted vulnerabilities and shortcomings in a number of ways, including the issues of essential resource shortages, underinvestment in public health services, lack of coordination and versatility among politicians, policymakers and health leaders, resulting in overloaded health systems, rapid case development, and high mortality, a more careful analysis of the changes needed in different health systems to satisfactorily face future emergencies is essential to be carried out. This should be directed especially towards improving the management of health systems, their coordination as well as reviewing related practices, even in the surgical field.

Core Tip: Reconstruction with a locoregional head and neck flap is a successful and reliable procedure, important in the treatment of head and neck cancer. Locoregional flaps have been reassessed during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, a period in which health care has been heavily impacted. The pandemic has been a trigger for reflection and learning in healthcare, as well as for accelerating scientific progress. However, many deficiencies in the healthcare provision have been exposed, which should redirect the goals in this field to optimize medical work as much as possible without negative repercussions on the outcomes.

- Citation: Lizambri D, Giacalone A, Shah PA, Tovani-Palone MR. Reconstruction surgery in head and neck cancer patients amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: Current practice and lessons for the future. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(7): 1434-1441

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i7/1434.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i7.1434

Healthcare facilities have been under tremendous pressure during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, which has led to the restructuring of services and rationalization of essential resources to reduce severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) transmission, as well as to empower and protect patients and staff. In this context, the vulnerabilities of health systems have had profound implications both for the care of patients and for society at large. If on the one hand the pandemic has caused unprecedented disruption in the way healthcare is provided and received, including delays in diagnosis and initiation of treatment, on the other this new scenario can be the basis for a sustainable healthcare environment in a post-pandemic world[1].

In light of these circumstances, the cancer patient’s surgery has been considerably adapted. Ensuring care to patients with surgical disease requires a unique and intimate relationship between the patient and surgeon, which corresponds to aspects that have been extremely compromised. Surgical workforce has faced different challenges, including the management of surgical workforce shortages, financial suffering due to the pandemic emergency, and an increasing number of more complex surgeries. Indeed, nonurgent and nonemergency surgeries have been rescheduled, due to lack of staff and unavailability of surgical rooms and supplies. In addition to the financial implications that have drastically impacted the field of surgery, in the United States of America, as in other regions of the world, there have also been pay cuts, furloughs, and layoffs. Many private surgical practices have been forced to shut down due to financial difficulties. The difficulties have been so pronounced, to the point of causing a considerable percentage of surgeons to retire early or even decide to leave the profession. All these issues further limit the surgical workforce at a time during which there is likely a greater need for these care[1].

Moreover, many patients with surgical diseases have avoided care due to the concern of acquiring COVID-19 in hospitals or doctors' offices[2]. As a result, surgical departments around the world have been forced to reschedule their activities, giving priority especially to urgent procedures[3]. In this connection, an important variation in epidemiological data has also been observed, with emphasis on the incidence of diagnoses of advanced stage cancers[4].

The COVID-19 pandemic has had important impacts on cancer screening, including delays in appointments for routine exams and limited diagnosis. Without adequate testing and decrease in the frequency of medical visits, there has been an overall reduction in treatment initiation. Treatment decisions have been influenced by the desire to minimize the risk of preventable infection. Therefore, healthcare professionals have experienced, in addition to greater vulnerability to SARS-CoV-2 infection, changes in their professional practice[1].

The oncology field has therefore suffered enormous repercussions. The pandemic control efforts have translated into a significant decline in the number of new cancer diagnoses, which may result in a large reduction in the record of the incidence of cases. Because of this, it is expected that new cancer incidence during the pandemic should have a worse prognosis than previously existing and already monitored cases, leading to a potential increase in advanced stage cancers and decreased survival[4,5]. In this context, head and neck cancer (HNC) patients may represent a priority given that in most cases both immediate treatment and an integrated strategy are required.

One of the most common HNC is squamous cell cancer, which corresponds to the seventh most common malignancy worldwide, with about 700000 new cases diagnosed annually. Its annual mortality rates exceed 50%, with an average of 375000 deaths. Current data suggest that a long interval between surgery and postoperative radiation therapy, as well as a delay in starting treatment may have a significant impact on prognosis, with worsening of overall survival[6]. Overall rates of T3-4 tumors were increased significantly in 2020 when compared to 2019[7].

However, this finding is not a consensus in the literature. A recent evaluation, carried out in one of the largest HNC centers in Germany, shows that there was no significant change in the number and severity of head and neck squamous cell cancer (HNSCC) diagnoses or in the time to initiation of therapy, in the period from April 1, 2020, to April 1, 2021. This study consisted of a single center and involved a retrospective review of 612 patients with newly diagnosed or recurrent HNSCC. The authors analyzed the diagnosis and treatment methods, considering the pre-COVID-19 period between March 1, 2019 and March 1, 2020 compared to the COVID-19 period from April 1, 2020 to April 1, 2021[8]. This divergence of results between studies may be due to the differences in impacts in the terri-tories/countries evaluated, since the pandemic resulted in impacts of different levels on health systems and population around the world. Moreover, given that there may even be excess hospital beds in some countries, the pandemic has turned this excess supply into an asset. Despite this, regions with fewer resources are expected to see cancer patient statistics vary enormously.

It is also worth noting that United States of America colleagues found in a retrospective cohort study that time-to-surgery may be an important independent predictor of survival for patients with HNSCC, with a significantly increased risk of death for delayed treatments[9]. Today, according to a multidisciplinary consensus statement on behalf of the Association of Anaesthetists, the Centre for Perioperative Care, the Federation of Surgical Specialty Associations, the Royal College of Anaesthetists and the Royal College of Surgeons of England, elective surgery should not be scheduled within 7 wk of a diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection unless the risks of deferring surgery outweigh the risk of postoperative morbidity or mortality associated with COVID-19[10].

In this period, head and neck surgery has been a challenge due to different factors, including the proximity of maxillofacial structures to the respiratory system and the need for intensive postoperative care related to potentially high comorbidity in patients undergoing high-risk procedures[11]. In light of this, safety management approaches are essential to provide surgical intervention to these patients during the pandemic.

Given that there are currently no uniform best-practice recommendations on surgical patient management, it is of great importance to discuss and propose new ideas for HNC case management[12]. This is critical for the HNC, since an indefinite delay may exacerbate treatment outcomes, resulting in cancer cases with a poor prognosis. The “Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza” Hospital published a review with instructions on “how to avoid delays in the diagnosis and treatment of head and neck tumors and to ensure a gradual return to elective procedures”. In particular, the Department of Head and Neck Research has reported, from its experience, how COVID-19 has crushed the management and outcomes of HNC patients, both out of fear of acquiring a nosocomial COVID-19 infection and inappropriate organization of services, which may delay diagnosis and worsen prognosis[13].

A further important point is that the psychological status of COVID-19 patients can also be a cause of delay in diagnosis or treatment in all medical fields[14]. However, related and well-designed prospective studies in the oncology field remain inconclusive. Many of the studies involving COVID-19 patients have presented publication bias due to heterogeneity, including those on COVID-19 biology, treatment protocols and targeted therapies. This was for example reported by some British colleagues while assessing the importance of immediate breast reconstruction (IBR) during the pandemic. IBR has been a common surgical dilemma facing the current period through the “the sooner the better “prerogative, given that it straddles both urgent and elective forms of surgery. Recent data suggest that surgery may have a negative impact on the outcome of COVID-19 positive patients who need IBR compared to HNSCC patients, when time to staging or time to treatment were analyzed. On the other hand, to date, there is very little published literature on perioperative risks and outcomes of COVID-19 patients after IBR, while there is little evidence of delays in staging and treatment time during the period of infection[15,16].

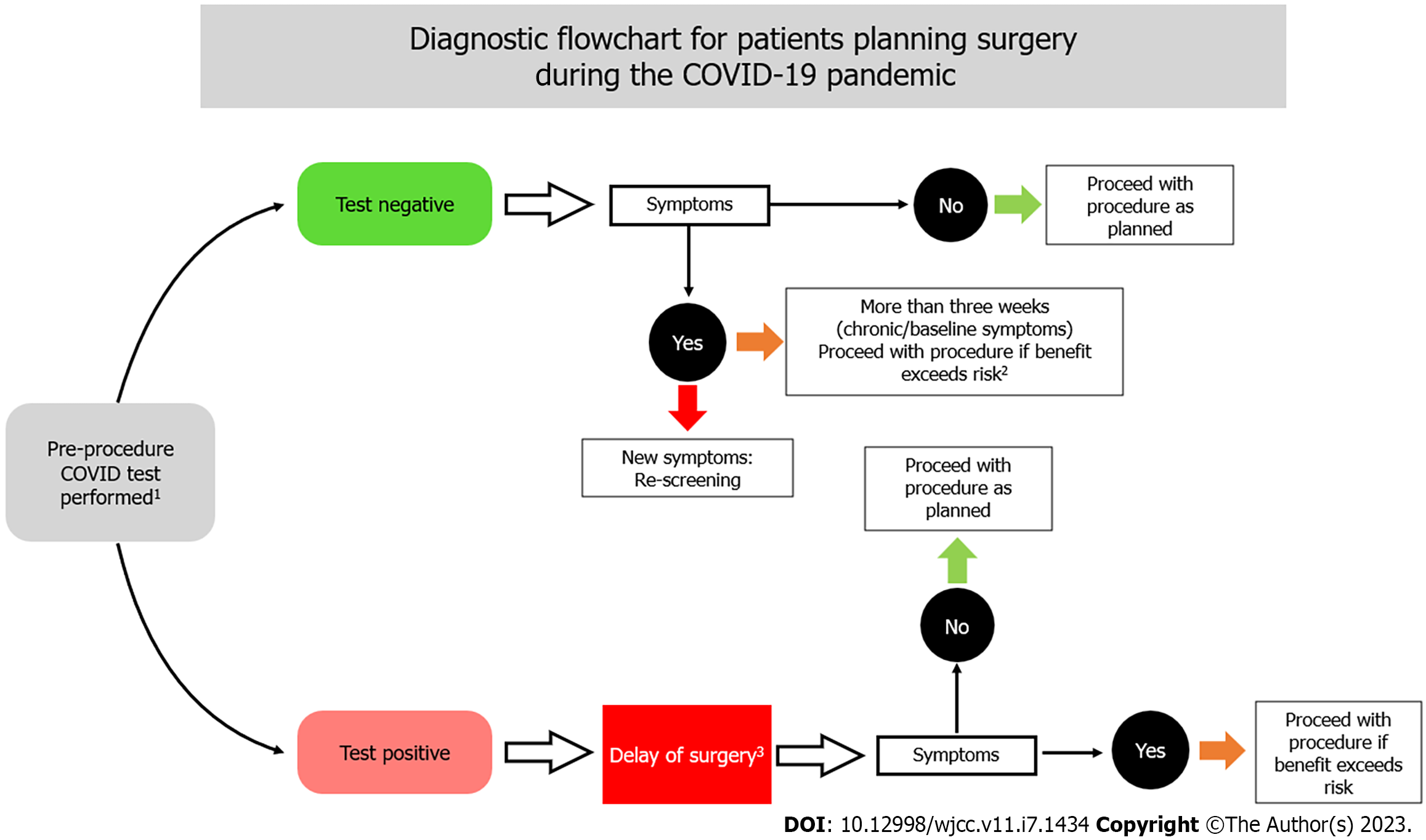

The diagnostic flowchart of HNC requires strict guidelines to reduce the risk of contagion, as well as to assess the patient's risk. “All known or suspected COVID-19-positive patients requiring surgical intervention must be treated as positive until proven otherwise” to minimize infection spread. When possible, all surgical procedures in suspected COVID-19 patients should be postponed until negative test results are obtained and symptoms disappear, while remembering the importance of early operation for prognosis benefit. A minimal staff should be involved when postponement is not possible. The risk of infection and the need of self-isolation have been relevant factors at different times, which should also impact experienced surgeons, leading to a dangerous shortage of senior specialists within surgical teams[17].

All staff must be properly trained to worn, remove and dispose of personal protection equipment, including masks (level 2 or 3 filtering facepiece depending on the aerosol-generating risk level), eye protection, gowns, socks, double non-sterile gloves, suites, and caps[17].

Furthermore, in order to reduce the time gap between cancer diagnosis and intervention in this period, tools that can quickly diagnose both COVID-19 patients and non-COVID-19 patients are needed. During the pandemic, attention has focused on the need for quick and simple diagnostic tools for infections caused by SARS-CoV-2 and its variants. In this case, the diagnosis is important to be achieved before an exacerbated immune response has taken place in COVID-19 positive patients. For asymptomatic cases, the justification is based on the already known impact that such people can have on the general epidemiology of the disease. Although nucleic acid testing, which detects RNA viral, is a viable and practical method in this context, fast and simple-to-operate test kits may also be highly effective. One such tool is the Loop-mediated isothermal amplification that detects SARS-CoV-2 with a simple colorimetric display. Colorimetric display of the test result is easy and without the need for expensive or complicated instruments[18].

The significant reduction in the time between the diagnosis of COVID-19 and the time for intervention thanks to these tools should considerably reduce the difficulties faced in managing hospitals, as well as provide safer surgeries in this period (Figure 1)[17,19-21].

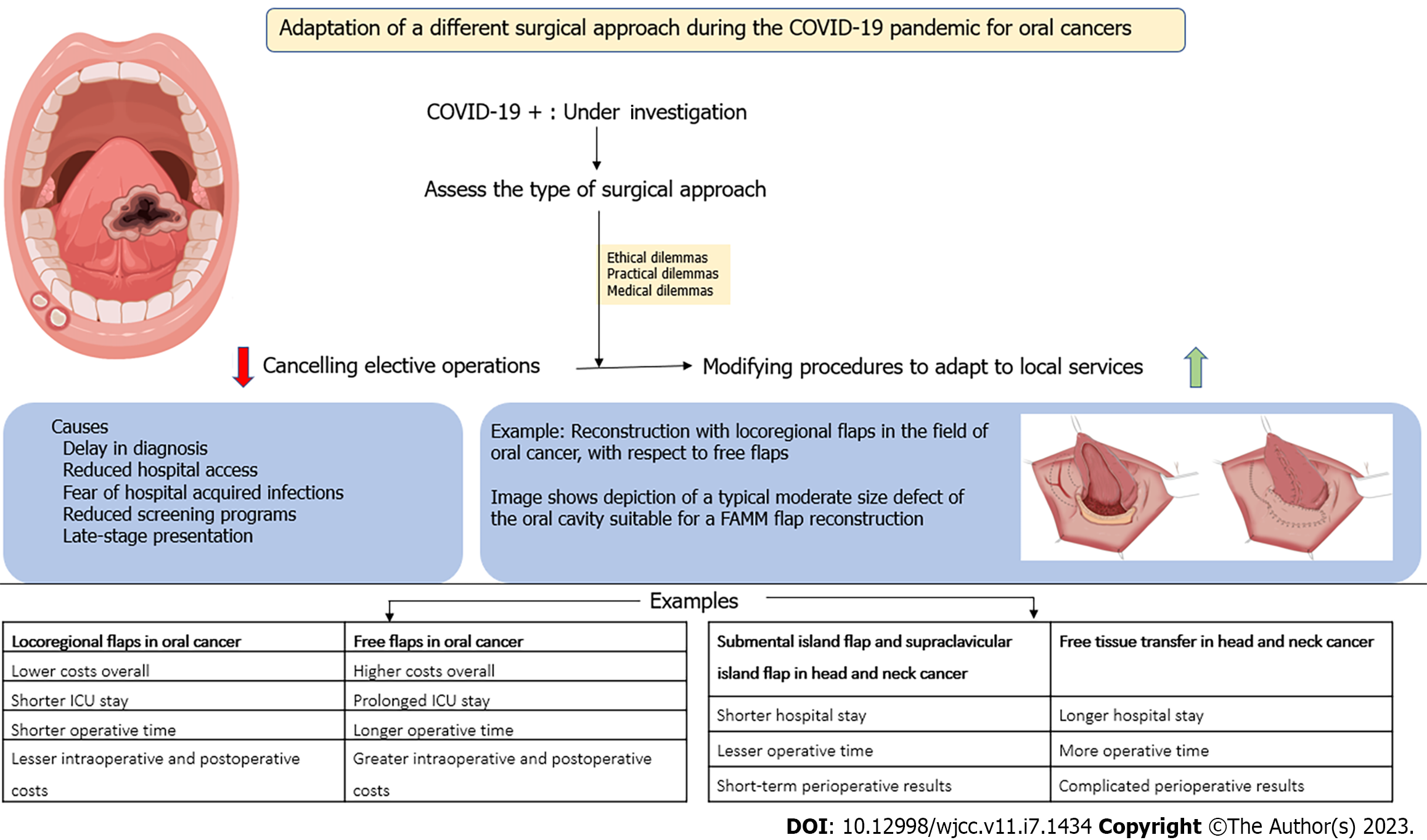

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the worldview of healthcare[22]. In some cases, a setback has been observed in relation to the most current guidelines, with the use of strategies different from the usual ones to respond to the difficulties of the health emergency. In this respect, approaches previously considered second choice or with limitations, such as locoregional flaps, began to be reconsidered[23]. Another important issue to be assessed in HNC patients in the operating room is the type of surgical approach. This is because the COVID-19 pandemic has reduced the ability to perform surgical procedures around the world, giving rise to a multitude of ethical, practical and medical dilemmas. Among the key challenges are canceling elective operations and modifying procedures to accommodate local services[24].

An interesting case of surgical technique adaptation in the field of oral cancer during the pandemic is the reconstruction with locoregional flaps, instead of free flaps. The high costs associated with prolonged intensive care unit stay, longer operative times, and greater intraoperative and postoperative costs of the free flap, in stark contrast with increased health care needs in this period, has led to a setback and reconsideration of the use of locoregional flaps[25]. Indeed, in this context, pedicled flaps such as the submental island flap (SMIF) and the supraclavicular island flap have become increasingly popular alternatives to free tissue transfer (FTT) for head and neck reconstruction[26]. The use of SMIF has increased considerably during the ongoing pandemic. Different studies report that SMIF requires “less operative time and hospital stay, as well as has comparable short-term perioperative outcomes to FTT” (Figure 2)[25-29].

In the review study conducted by Jørgensen et al[28], all included studies included SMIF or free flap alternative used for oral or lateral skull/parotidectomy defect reconstruction. The authors described varied aspects between 155 SMIFs vs 198 FTTs, such as operative time, in which the SMIF group had a statistically significantly shorter operative time than the FTT group; and length of stay, with evidence of shorter hospital admissions for SMIF. Another important finding was the lower number of wound complications in the donor area for the SMIF group compared to the FTT group. However, the indication to SMIF is more restricted, given that the SMIF can be used safely in selected patients with level I lymph node metastases, evidence underlined by Thai colleagues. These researchers studied patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity, who underwent surgical resection with reconstruction using a SMIF[30]. However, such an indication may be a problem for the future, in which there may be a higher incidence of late diagnosis of cancer cases.

If, on the one hand, many studies have focused on the effective superiority of free flaps compared to locoregional flaps, evaluating all related aspects, including preoperative assessment and consultation, intraoperative and postoperative pathology and pathologist costs, post-operative follow-up, and adjuvant therapy, on the other hand, current evidence highlights the preference for the use of locoregional flaps, largely due to re-evaluating of their use during the pandemic[25].

The COVID-19 pandemic has taught us a lot. We have learnt that the healthcare paradigm must be transformed after the pandemic[28]. This health emergency has highlighted vulnerabilities and deficiencies that resulted in overwhelmed health systems, rapid case development, and high mortality. Therefore, the healthcare paradigm needs to be transformed, adding new technological advancements in all branches of medical services, since local healthcare systems must be powerful to deal with this type of emergency, in this case mainly facilitating the implementation of new technological advances and methods of surgical research, surgical practice, and global scientific research. The need for faster coordination in the field of healthcare has also demonstrated the need for improvements in patient tracking, the use of computerized innovation for data management and sharing, reinforcing the importance of multidisciplinary and collective care to deal with follow-up and management of serious conditions[22].

Effective coordination between healthcare organizations is therefore essential to ensure a quick response to the challenges of this period. International organizations are expected to be the focus of this coordination[31]. On the other hand, although most countries adopted similar measures in the early months of the pandemic, responses have begun to vary as the pandemic has progressed. The results of a comparative study on decision-making regarding COVID-19 involving 16 countries on five continents suggest that the diversity of responses is associated with pre-existing weaknesses in these three spheres combined-public health, economy, and political system. Even countries with great availability of financial and technological resources have responded chaotically to the pandemic, mainly due to other pre-existing weaknesses, such as high levels of socioeconomic inequality and political polarization[32].

As far as HNC is concerned, we must be prepared for the worst. Given that an increase in patients with late clinical presentations is expected, specialized healthcare services need to be proactive in anticipating and preparing to satisfactorily manage all these cases[33].

The impact of the pandemic may lead to a delay in the diagnosis or treatment of non-COVID-19-related illnesses and this is unavoidable in all medical fields, whether the allocation of medical resources is effective or not[14]. Changes in the number of newly identified cancer patients before and during the pandemic have been analyzed in many countries: the Netherlands Cancer Registry reported a 40% decline in weekly cancer incidence, and the United Kingdom has experienced a 75% decline in referrals for suspected cancer since COVID-19 restrictions were implemented[34].

A seminal research by Luo et al[35] underscores these impacts on cancer incidence and mortality in Australia. The authors estimate that a 1-year interruption to health-care services and a 26-wk delay in treatment would lead to 1719 additional deaths in the country between 2020-44 among colorectal cancer patients. It is also important to highlight that important epidemiological changes have been observed to different types of cancer. In a study conducted in the United States of America, researchers found accelerated declines in lung cancer incidence rates, with a slowdown for breast cancer and stabilization for prostate cancer while the incidence continued to increase by about 1% annually for cancers of the oral cavity and pharynx, all of which are burdened by the lack of screening[36].

Finally and in short, regarding HCN reconstruction surgery, different studies, as analyzed by Jørgensen et al[28], suggest that SMIF reduces length of stay and operating time without compromising oncologic safety and donor site morbidity compared to FTT alternatives. Moreover, SMIF has been shown to be a viable, versatile, and reliable flap, which should be added to the surgical repertoire when there are circumstances that promote its indication, such as during a pandemic emergency.

| 1. | Bernacki K, Keister A, Sapiro N, Joo JS, Mattle L. Impact of COVID-19 on patient and healthcare professional attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors toward the healthcare system and on the dynamics of the healthcare pathway. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:1309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kibbe MR. Surgery and COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324:1151-1152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Moletta L, Pierobon ES, Capovilla G, Costantini M, Salvador R, Merigliano S, Valmasoni M. International guidelines and recommendations for surgery during Covid-19 pandemic: A Systematic Review. Int J Surg. 2020;79:180-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 32.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | London JW, Fazio-Eynullayeva E, Palchuk MB, Sankey P, McNair C. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Cancer-Related Patient Encounters. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2020;4:657-665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 38.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Maringe C, Spicer J, Morris M, Purushotham A, Nolte E, Sullivan R, Rachet B, Aggarwal A. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer deaths due to delays in diagnosis in England, UK: a national, population-based, modelling study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:1023-1034. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1142] [Cited by in RCA: 1189] [Article Influence: 198.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Schutte HW, Heutink F, Wellenstein DJ, van den Broek GB, van den Hoogen FJA, Marres HAM, van Herpen CML, Kaanders JHAM, Merkx TMAW, Takes RP. Impact of Time to Diagnosis and Treatment in Head and Neck Cancer: A Systematic Review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;162:446-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tevetoğlu F, Kara S, Aliyeva C, Yıldırım R, Yener HM. Delayed presentation of head and neck cancer patients during COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;278:5081-5085. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Balk M, Rupp R, Craveiro AV, Allner M, Grundtner P, Eckstein M, Hecht M, Iro H, Gostian AO. The COVID-19 pandemic and its consequences for the diagnosis and therapy of head and neck malignancies. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2022;26:284-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rygalski CJ, Zhao S, Eskander A, Zhan KY, Mroz EA, Brock G, Silverman DA, Blakaj D, Bonomi MR, Carrau RL, Old MO, Rocco JW, Seim NB, Puram SV, Kang SY. Time to Surgery and Survival in Head and Neck Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28:877-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | El-Boghdadly K, Cook TM, Goodacre T, Kua J, Blake L, Denmark S, McNally S, Mercer N, Moonesinghe SR, Summerton DJ. SARS-CoV-2 infection, COVID-19 and timing of elective surgery: A multidisciplinary consensus statement on behalf of the Association of Anaesthetists, the Centre for Peri-operative Care, the Federation of Surgical Specialty Associations, the Royal College of Anaesthetists and the Royal College of Surgeons of England. Anaesthesia. 2021;76:940-946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Thacoor A, Sofos SS, Miranda BH, Thiruchelvam J, Perera EHK, Randive N, Tzafetta K, Ahmad F. Outcomes of major head and neck reconstruction during the COVID-19 pandemic: The St. Andrew's centre experience. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2021;74:2133-2140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Morales-Perez MJ, Gallardo-Calero I, Rivas-Nicolls D, Gelabert Mestre S, Garcia Forcada I, Soldado F. Reconstruction of COVID-19 vasculitis-related thumb necrosis with a microsurgical free flap. Microsurgery. 2021;41:393-395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Longo F, Trecca EMC, D'Ecclesia A, Copelli C, Tewfik K, Manfuso A, Pederneschi N, Mastromatteo A, Russo MA, Pansini A, Lacerenza LM, Marano PG, Cassano L. Managing head and neck cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: the experience of a tertiary referral center in southern Italy. Infect Agent Cancer. 2021;16:9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Li Z, Jiang Y, Yu Y, Kang Q. Effect of COVID-19 Pandemic on Diagnosis and Treatment Delays in Urological Disease: Single-Institution Experience. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2021;14:895-900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jallali N, Hunter JE, Henry FP, Wood SH, Hogben K, Almufti R, Hadjiminas D, Dunne J, Thiruchelvam PTR, Leff DR. The feasibility and safety of immediate breast reconstruction in the COVID-19 era. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2020;73:1917-1923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yao P, Cooley V, Kuhel W, Tassler A, Banuchi V, Long S, Savenkov O, Kutler DI. Times to Diagnosis, Staging, and Treatment of Head and Neck Cancer Before and During COVID-19. OTO Open. 2021;5:2473974X211059429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Coccolini F, Perrone G, Chiarugi M, Di Marzo F, Ansaloni L, Scandroglio I, Marini P, Zago M, De Paolis P, Forfori F, Agresta F, Puzziello A, D'Ugo D, Bignami E, Bellini V, Vitali P, Petrini F, Pifferi B, Corradi F, Tarasconi A, Pattonieri V, Bonati E, Tritapepe L, Agnoletti V, Corbella D, Sartelli M, Catena F. Surgery in COVID-19 patients: operational directives. World J Emerg Surg. 2020;15:25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 274] [Cited by in RCA: 268] [Article Influence: 44.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Huang WE, Lim B, Hsu CC, Xiong D, Wu W, Yu Y, Jia H, Wang Y, Zeng Y, Ji M, Chang H, Zhang X, Wang H, Cui Z. RT-LAMP for rapid diagnosis of coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Microb Biotechnol. 2020;13:950-961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 393] [Cited by in RCA: 355] [Article Influence: 59.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation. Preoperative COVID testing: examples from around the U.S. November 11, 2020. In: Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation [Internet]. [cited 28 Dec 2022]. Available from: https://www.apsf.org/novel-coronavirus-covid-19-resource-center/preoperative-covid-testing-examples-from-around-the-u-s/. |

| 20. | COVIDSurg Collaborative; GlobalSurg Collaborative. Timing of surgery following SARS-CoV-2 infection: an international prospective cohort study. Anaesthesia. 2021;76:748-758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 419] [Cited by in RCA: 389] [Article Influence: 77.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | COVIDSurg Collaborative. Delaying surgery for patients with a previous SARS-CoV-2 infection. Br J Surg. 2020;107:e601-e602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 22. | Syed SA, Zahid H, Khan SJ. Changing the paradigm of healthcare after COVID-19 - a narrative review. Pak J Sci. 2021;73:313-324. |

| 23. | Gabrysz-Forget F, Tabet P, Rahal A, Bissada E, Christopoulos A, Ayad T. Free vs pedicled flaps for reconstruction of head and neck cancer defects: a systematic review. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;48:13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Macleod J, Mezher S, Hasan R. Surgery during COVID-19 crisis conditions: can we protect our ethical integrity against the odds? J Med Ethics. 2020;46:505-507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Forner D, Phillips T, Rigby M, Hart R, Taylor M, Trites J. Submental island flap reconstruction reduces cost in oral cancer reconstruction compared to radial forearm free flap reconstruction: a case series and cost analysis. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;45:11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sittitrai P, Reunmakkaew D, Srivanitchapoom C. Submental island flap vs radial forearm free flap for oral tongue reconstruction: a comparison of complications and functional outcomes. J Laryngol Otol. 2019;133:413-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Mooney SM, Sukato DC, Azoulay O, Rosenfeld RM. Systematic review of submental artery island flap vs free flap in head and neck reconstruction. Am J Otolaryngol. 2021;42:103142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Jørgensen MG, Tabatabaeifar S, Toyserkani NM, Sørensen JA. Submental Island Flap vs Free Flap Reconstruction for Complex Head and Neck Defects. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;161:946-953. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ibrahim B, Rahal A, Bissada E, Christopoulos A, Guertin L, Ayad T. Reconstruction of medium-size defects of the oral cavity: radial forearm free flap vs facial artery musculo-mucosal flap. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;50:67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Sittitrai P, Srivanitchapoom C, Reunmakkaew D, Yata K. Submental island flap reconstruction in oral cavity cancer patients with level I lymph node metastasis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;55:251-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Novelli G, Biancolella M, Mehrian-Shai R, Erickson C, Godri Pollitt KJ, Vasiliou V, Watt J, Reichardt JKV. COVID-19 update: the first 6 mo of the pandemic. Hum Genomics. 2020;14:48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Silva HPD, Lima LD. Politics, economy, and health: lessons from COVID-19. Cad Saude Publica. 2021;37:e00200221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Chone CT. Increased mortality from head and neck cancer due to SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;87:1-2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Kaufman HW, Chen Z, Niles J, Fesko Y. Changes in the Number of US Patients With Newly Identified Cancer Before and During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2017267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 285] [Article Influence: 47.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 35. | Luo Q, O'Connell DL, Yu XQ, Kahn C, Caruana M, Pesola F, Sasieni P, Grogan PB, Aranda S, Cabasag CJ, Soerjomataram I, Steinberg J, Canfell K. Cancer incidence and mortality in Australia from 2020 to 2044 and an exploratory analysis of the potential effect of treatment delays during the COVID-19 pandemic: a statistical modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2022;7:e537-e548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72:7-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4235] [Cited by in RCA: 11975] [Article Influence: 2993.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: India

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kadriyan H, Indonesia; Leowattana W, Thailand; Liu J, China; Pisani P, Italy S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: A P-Editor: Chen YX