Published online Feb 6, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i4.972

Peer-review started: December 7, 2022

First decision: December 19, 2022

Revised: December 28, 2022

Accepted: January 12, 2023

Article in press: January 12, 2023

Published online: February 6, 2023

Processing time: 60 Days and 8.1 Hours

Omental infarction (OI) is a surgical abdominal disease that is not common in adults and is very rare in children. Similar to various acute abdominal pain diseases including appendicitis, diagnosis was previously achieved by diagnostic laparotomy but more recently, ultrasonography or computed tomography (CT) examination has been used.

A 6-year-old healthy boy with no specific medical history visited the emergency room with right lower abdominal pain. He underwent abdominal ultrasonography by a radiologist to rule out acute appendicitis. He was discharged with no significant sonographic finding and symptom relief. However, the symptoms persisted for 2 more days and an outpatient visit was made. An outpatient abdominal CT was used to make a diagnosis of OI. After laparoscopic operation, his symptoms resolved.

In children’s acute abdominal pain, imaging studies should be performed for appendicitis and OI.

Core Tip: We report the case of a 6-year-old boy with omental infarction (OI) diagnosed by computed tomography (CT) and missed by ultrasonography. The patient who complained of right abdominal pain underwent a laboratory test and ultrasound examination in the emergency room. However, there were no specific findings, so he was discharged. However, the abdominal pain persisted, so a CT scan was performed at the outpatient clinic. Then, OI was diagnosed, and he underwent laparoscopic operation and was discharged after hospitalization. Even if there are no specific findings by ultrasonography, CT examination should be carefully considered.

- Citation: Hwang JK, Cho YJ, Kang BS, Min KW, Cho YS, Kim YJ, Lee KS. Omental infarction diagnosed by computed tomography, missed with ultrasonography: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(4): 972-978

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i4/972.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i4.972

Omental infarction (OI) is a rare disease of acute abdominal pain in children[1]. Abdominal pain is a common cause of emergency department visits and appendicitis is the most common cause of abdomen surgery in children[2]. OI was reported in about 0.1% to 0.5% of children undergoing surgery for appendicitis[3]. Therefore, it is common for many doctors to initially suspect OI as appendicitis or other diseases, and many cases have been diagnosed intraoperatively[2]. Currently, because of advances in imaging technologies, the number of cases diagnosed by abdominal ultrasound and computed tomography (CT), rather than surgery, is increasing[3-5]. Although abdominal ultrasound and CT have high accuracy, CT has higher sensitivity for OI diagnosis[6].

This case was suspected of appendicitis in the emergency department, and an ultrasound examination was performed, but no singularity was found. The patient was discharged but diagnosed by an outpatient CT scan two days later.

A 6-year-old healthy boy with no specific medical history visited the emergency room with right lower abdominal pain that started two days before the visit.

The day before the visit, he received a prescription from the local clinic, but there was no improvement, so he went to the emergency room.

A history of abdominal pain was not presented.

No family history of abdominal disease.

The patient’s height and weight were 115 cm and 29 kg, respectively. His vital signs in the emergency room were as follows: Body temperature, 37 °C; heart rate, 110 beats/min; and respiratory rate, 22 breaths/min. Tenderness of the right lower quadrant (RLQ) was observed, but rebound tenderness, muscle guarding, and rigid abdomen were not observed.

Not performed, because radiological findings were not significantly abnormal and the patient’s symptoms were relieved.

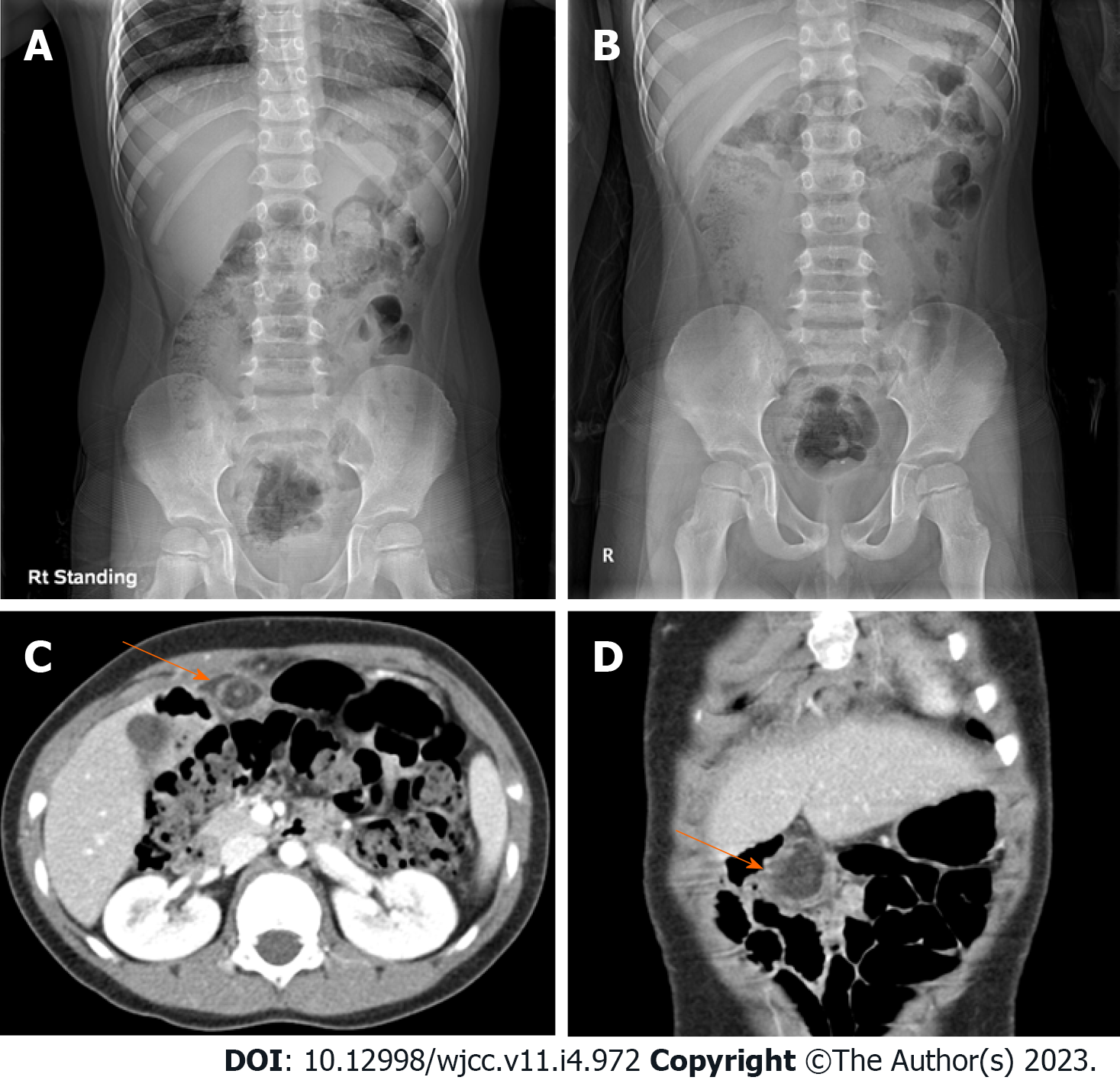

Abdominal X-ray examination was performed, and gaseous distension was observed (Figure 1A and B). Abdominal ultrasound was performed after being referred to a radiologist to rule out acute appendicitis. Ultrasonography showed the appendix had collapsed and tenderness was not present. In addition, there was no significant wall thickening or tenderness in the scanned bowel loop, and no abnormal fluid collection or enlarged lymph node was seen in the abdominal cavity. There were no abnormal findings on ultrasonography.

Gastrointestinal disease; abdominal pain, right lower quadrant.

The symptoms improved spontaneously and the patient was discharged.

The patient visited the pediatric outpatient department two days later due to aggravated abdominal pain. At the visit, he had a limp, severe pain around the periumbilical area, no fever, and no symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, or anorexia. On physical examination, tenderness of the RLQ remained. A glycerin enema was performed under the suspicion of fecal impaction on initial X-ray, but there were no feces and no palpable stool by digital rectal examination. An additional physical examination showed rebound tenderness and a laboratory exam was performed. Inflammatory findings were as follows: white blood cell (WBC) 13200/mm3, absolute neutrophil count (ANC) 9540/mm3, erythrocyte sedimentation rate 40 mm/hr, and C-reactive protein (CRP) 1.2 mg/dL, but no electrolyte imbalance was observed. The calculated pediatric appendicitis score was 7, which was likely appendicitis, and contrast enhanced abdomen CT scan was examined. The appendix was collapsed, and no evidence of acute appendicitis was found. Abdominal CT scan showed approximately 4 cm of fat lobule below the umbilical ligament of the liver left lobe. A hyperdense halo and surrounding fat stranding were detected in the periphery of the fat lobule. The vessel of the upper portion inside the fat lobule showed a whirling sign. These abdominal CT findings were consistent with OI, and surgery was performed on the same day in consultation with the pediatric surgeon.

The final diagnosis was OI.

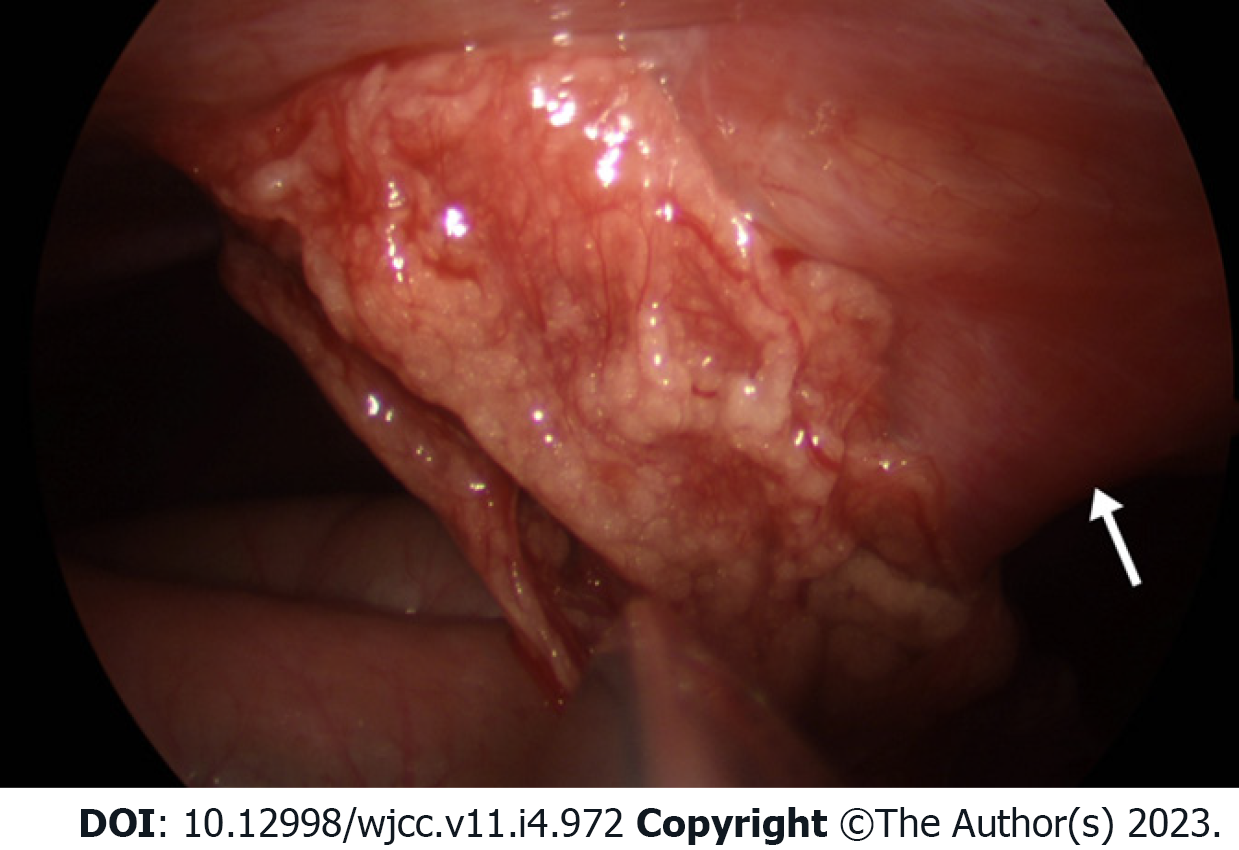

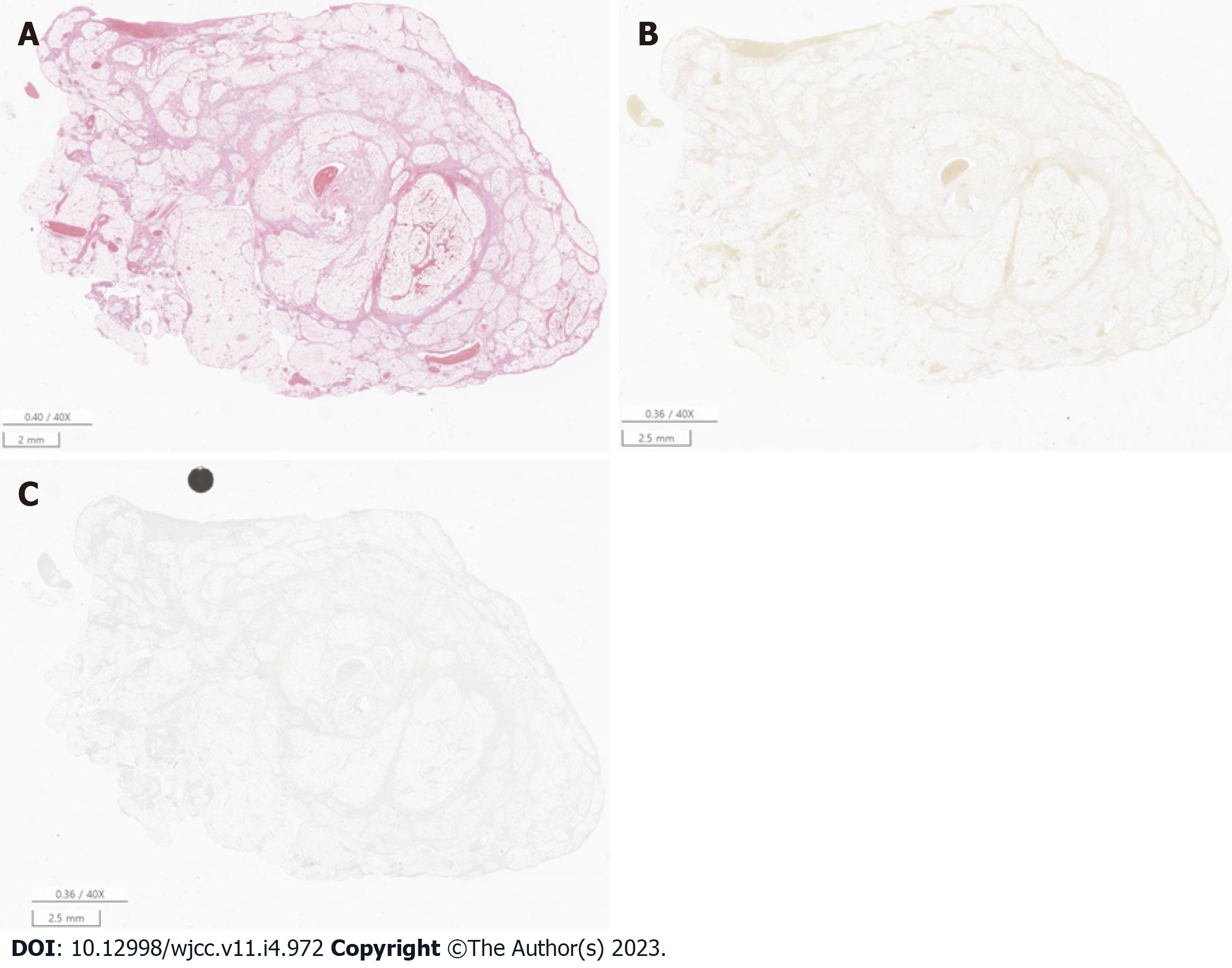

The patient underwent laparoscopic surgery (Figure 2) and OI was confirmed by histological examination (Figure 3).

After laparoscopic surgery, the patient's pain improved and he was discharged at POD 5 without any complications.

An OI usually affects only one part of the omentum and is commonly seen on the right side[7]. Therefore, it is often necessary to differentiate OI from appendicitis because the side of the abdominal pain is similar[2]. The cause of OI was unclear. Explanations might include abnormal arterial supply to the omentum, torsion around the omental pedicle, or venous torsion usually involving the right epiploic vessels[1,8]. There are several risk factors for OI such as obesity, trauma, coughing, and overeating and such factors can cause thrombosis or infarction[8]. The patient reported that he had recently gained weight rapidly and was obese with a Body Mass Index of 21.9 kg/m2 (99.5 percentile).

OI occurs in approximately 0.1% to 0.5% of children evaluated for acute appendicitis[3]. The male to female ratio is usually 2:1[9]. OI was reported in 15% of children and 85% of adults, so it is very rare in children and very difficult to diagnose at first examination[10]. Abdominal pain is common in children and most are non-surgical diseases such as constipation and enteritis. Appendicitis is the most common pediatric surgical abdominal disease in children, and it accounts for 20%-30% of children's colic[11,12]. Other surgical abdominal diseases of children are intussusception, Meckel’s diverticulum, and so on. Intussusception mainly occurs from 6 mo to 2 years old, and Meckel’s diverticulum represents an intestinal obstruction and/or painless gastrointestinal hemorrhage[11,13]. In our patient, considering his age and symptoms, the likelihood of intussusception and Meckel’s diverticulum was low, and appendicitis was evaluated. When the patient visited the emergency room, small bowel and appendix ultrasonography were performed by an expert radiologist. The patient, who had no significant abnormal findings by ultrasonography, was discharged.

When he came to the outpatient clinic two days later, an enema was administered first because constipation was suspected by simple abdomen X-ray examination. Because there were no abnormal findings by enema and rectal examination, it was necessary to differentiate other abdominal diseases. Therefore, we performed a laboratory study. Then, we calculated the pediatric appendicitis score as 7 points (likely appendicitis), so it was necessary to differentiate other abdominal diseases by CT[14,15]. Previous studies revealed that leukocytosis and fever are minor symptoms of OI[6]. A previous study compared OI and acute appendicitis in children and suggested that OI should be considered in patients with lower right abdominal pain with a neutrophil fraction < 77%[16]. The results showed that WBCs (11928 ± 1042 and 16207 ± 857; P value 0.024), neutrophils (8080 ± 832 and 14057 ± 781; P value 0.001), and CRP (3.349 ± 1.155 and 9.082 ± 1.659 mg/dL; P value 0.008) were significantly different between OI and acute appendicitis[16]. These findings were consistent with our case. Our patient had leukocytosis (WBC > 10000) and neutrophilia (ANC > 7500). In children and adolescents, ultrasonography is preferred over CT because of the risk of exposure to radiation[3]. On ultrasonography, OI shows increased echogenicity of noncompressible omental fat in a painful area[17,18]. In children, OI is difficult to diagnose via ultrasound when communication or symptoms are unclear. In this case, the patient was considered to have a negative ultrasound finding because the symptom was unclear and the presentation of abdominal pain was not localized. Clinically, OI is difficult to distinguish from acute appendicitis and often misdiagnosed as acute appendicitis, leading to surgery[19]. Although abdominal ultrasonography is a safe diagnostic method, CT is the gold standard for the diagnosis of OI due to its high specificity and sensitivity[3,20]. Therefore, CT may be considered if acute appendicitis is not clearly ruled out or if abdominal pain persists even after acute appendicitis is excluded. The CT findings of acute appendicitis, which is the most common cause requiring surgery for RLQ pain, include a distended appendix with a diameter of more than 6 mm, wall thickening of more than 3 mm, and secondary inflammatory periappendiceal chances. The sensitivity and specificity of CT for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis are within the range of 94%-98%[21]. However, because children are vulnerable to radiation, the same dose of radiation is more harmful to them than to adults. The abdominal CT scan was examined with a tube voltage of 100 kVp, and the dose length product was 166 mGycm, which was much lesser than the abdominal CT dose for adults. Nevertheless, additional efforts should be devoted to reducing the radiation dose as much as possible in the abdominal CT examination for children. Ultrasonography is more useful for follow-up to check whether OI has resolved after conservative treatment without radiation exposure[3].

As for OI treatment, it has not yet been precisely determined whether surgical or conservative treatment is better[6]. Some recommend conservative treatment because OI is a self-limiting disease that occurs over 10 to 15 days, whereas others insist on surgical treatment for quick recovery and prevention of a secondary abscess[22,23]. This patient complained of severe pain, and with the consent of his parents, the OI was treated with surgery.

In conclusion, if a case has right abdominal pain and no specific findings on ultrasonography, a CT examination should be carefully considered if symptoms do not improve by follow-up or other diseases are suspected. However, because there is a risk of radiation exposure, its implementation should be minimized.

| 1. | Arigliani M, Dolcemascolo V, Nocerino A, Pasqual E, Avellini C, Cogo P. A Rare Cause of Acute Abdomen: Omental Infarction. J Pediatr. 2016;176:216-216.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Di Nardo G, Di Serafino M, Gaglione G, Mercogliano C, Masoni L, Villa MP, Parisi P, Ziparo C, Vassallo F, Evangelisti M, Vallone G, Esposito F. Omental Infarction: An Underrecognized Cause of Right-Sided Acute Abdominal Pain in Children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2021;37:e1555-e1559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kozłowski M, Piotrowska O, Giżewska-Kacprzak K. Omental Infarction in a Child-Conservative Management as an Effective and Safe Strategy in Diagnosis and Treatment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tonerini M, Calcagni F, Lorenzi S, Scalise P, Grigolini A, Bemi P. Omental infarction and its mimics: imaging features of acute abdominal conditions presenting with fat stranding greater than the degree of bowel wall thickening. Emerg Radiol. 2015;22:431-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | McCusker R, Gent R, Goh DW. Diagnosis and management of omental infarction in children: Our 10 year experience with ultrasound. J Pediatr Surg. 2018;53:1360-1364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rimon A, Daneman A, Gerstle JT, Ratnapalan S. Omental infarction in children. J Pediatr. 2009;155:427-431.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | van Breda Vriesman AC, de Mol van Otterloo AJ, Puylaert JB. Epiploic appendagitis and omental infarction. Eur J Surg. 2001;167:723-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Bachar GN, Shafir G, Postnikov V, Belenky A, Benjaminov O. Sonographic diagnosis of right segmental omental infarction. J Clin Ultrasound. 2005;33:76-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Coulier B. Segmental omental infarction in childhood: a typical case diagnosed by CT allowing successful conservative treatment. Pediatr Radiol. 2006;36:141-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Esposito F, Ferrara D, Schillirò ML, Grillo A, Diplomatico M, Tomà P. "Tethered Fat Sign": The Sonographic Sign of Omental Infarction. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2020;46:1105-1110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nguyen PN, Petchers A, Choksi S, Edwards MJ. Common Conditions II: Acute Appendicitis, Intussusception, and Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Surg Clin North Am. 2022;102:797-808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Patterson KN, Deans KJ, Minneci PC. Shared decision-making in pediatric surgery: An overview of its application for the treatment of uncomplicated appendicitis. J Pediatr Surg. 2022;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hansen CC, Søreide K. Systematic review of epidemiology, presentation, and management of Meckel's diverticulum in the 21st century. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e12154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 24.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Goldman RD, Carter S, Stephens D, Antoon R, Mounstephen W, Langer JC. Prospective validation of the pediatric appendicitis score. J Pediatr. 2008;153:278-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Samuel M. Pediatric appendicitis score. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:877-881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 330] [Cited by in RCA: 341] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yang YL, Huang YH, Tiao MM, Tang KS, Huang FC, Lee SY. Comparison of clinical characteristics and neutrophil values in omental infarction and acute appendicitis in children. Pediatr Neonatol. 2010;51:155-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Grattan-Smith JD, Blews DE, Brand T. Omental infarction in pediatric patients: sonographic and CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178:1537-1539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Schlesinger AE, Dorfman SR, Braverman RM. Sonographic appearance of omental infarction in children. Pediatr Radiol. 1999;29:598-601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lim S, Hong HS, Kim YT, Lee HK, Lee MH. Computed Tomography and Ultrasound of Omental Infarction in Children: Differential Diagnoses of Right Lower Quadrant Pain. J Korean Soc Radiol. 2013;68:431-437. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 20. | Bianchi F, Leganés Villanueva C, Brun Lozano N, Goruppi I, Boronat Guerrero S. Epiploic Appendagitis and Omental Infarction as Rare Causes of Acute Abdominal Pain in Children. Pediatr Rep. 2021;13:76-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Moteki T, Horikoshi H. New CT criterion for acute appendicitis: maximum depth of intraluminal appendiceal fluid. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:1313-1319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Balthazar EJ, Lefkowitz RA. Left-sided omental infarction with associated omental abscess: CT diagnosis. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1993;17:379-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Loh MH, Chui HC, Yap TL, Sundfor A, Tan CE. Omental infarction--a mimicker of acute appendicitis in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:1224-1226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gao C, China; Yang L, China; Yao J, China; Fan L, China S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang LL