Published online Nov 26, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i33.8071

Peer-review started: September 9, 2023

First decision: October 24, 2023

Revised: October 29, 2023

Accepted: November 14, 2023

Article in press: November 14, 2023

Published online: November 26, 2023

Processing time: 75 Days and 23 Hours

Cerebral proliferative angiopathy (CPA) is a rare subtype of arteriovenous malformation. It is extremely rare in pediatric patients and has serious implications for developing children. However, reports of these disorders worldwide are limited, and no uniform reference for diagnosis and treatment options exists. We report the case of a 6-year-old with CPA having predominantly neurological dysfunction and review the literature on pediatric CPA.

We report the case of a pediatric patient with CPA analyzed using digital sub

This report of rare pediatric CPA can inform and advance clinical research on congenital cerebrovascular diseases.

Core Tip: Cerebral proliferative angiopathy (CPA) is a type of ischemic cerebrovascular disease that is extremely rare in pediatric patients and has serious implications for developing children. However, reports of these disorders are limited, and no uniform reference for diagnosis and treatment options exists. This article reviews the literature on pediatric CPA from a case of CPA in a child with predominantly neurological dysfunction. We summarize the relevant clinical, diagnostic, therapeutic, and pathogenic explorations and provide suggestions for subsequent research on this disorder.

- Citation: Luo FR, Zhou Y, Wang Z, Liu QY. Cerebral proliferative angiopathy in pediatric age presenting as neurological disorders: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(33): 8071-8077

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i33/8071.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i33.8071

Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are diagnosed increasingly as cerebrovascular pathologies because of improved diagnostic techniques. Cerebral proliferative angiopathy (CPA) is a rare variant of AVM that has unique clinical and imaging characteristics; its vascular structures are smaller than the usual blood-supplying arteries and draining veins with the lesion characterized by diffuse proliferating vessels intermixed with the brain parenchyma. CPA lesions often exhibit an epidural blood supply. Patients with CPA commonly present with seizures accompanied by headaches and intracranial hemorrhage[1]; some experience neurological deficits. Unlike AVM, CPA is more likely to be caused by ischemia than hemorrhage. CPA affects young women primarily[1] and is extremely rare in pediatrics.

Based on the histological studies of Chin et al[2], CPA vessels have been hypothesized to proliferate in response to unknown signals derived from cortical ischemia. However, the pathogenesis of CPA remains unknown. This study reports the case of a 6-year-old with CPA who presented with predominantly neurological dysfunction. We also review the literature on pediatric CPA, summarize the relevant clinical, diagnostic, therapeutic, and pathogenic explorations, and provide suggestions for subsequent research on this disorder.

The patient was a 6-year-old girl who had experienced transient unsteadiness and slurred speech for 2 years.

The patient was diagnosed with Moyamoya disease using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) at another hospital, where she presented with transient unsteadiness and slurred speech lasting several minutes per episode. She complained of the symptoms after eating peppers.

The patient had no previous history of any disease.

The patient had no known exposure to epidemic areas/water, epidemics, industrial toxins, dust, or radioactive material. The child’s uncle had a history of Moyamoya disease; no other family hereditary diseases or tumors were reported.

The positive signs on physical examination included occasional slurred speech and incomplete right eyelid closure.

The patient’s liver function, renal function, electrolyte levels, blood coagulation, and urine test results were all negative; blood tests revealed no significant abnormalities.

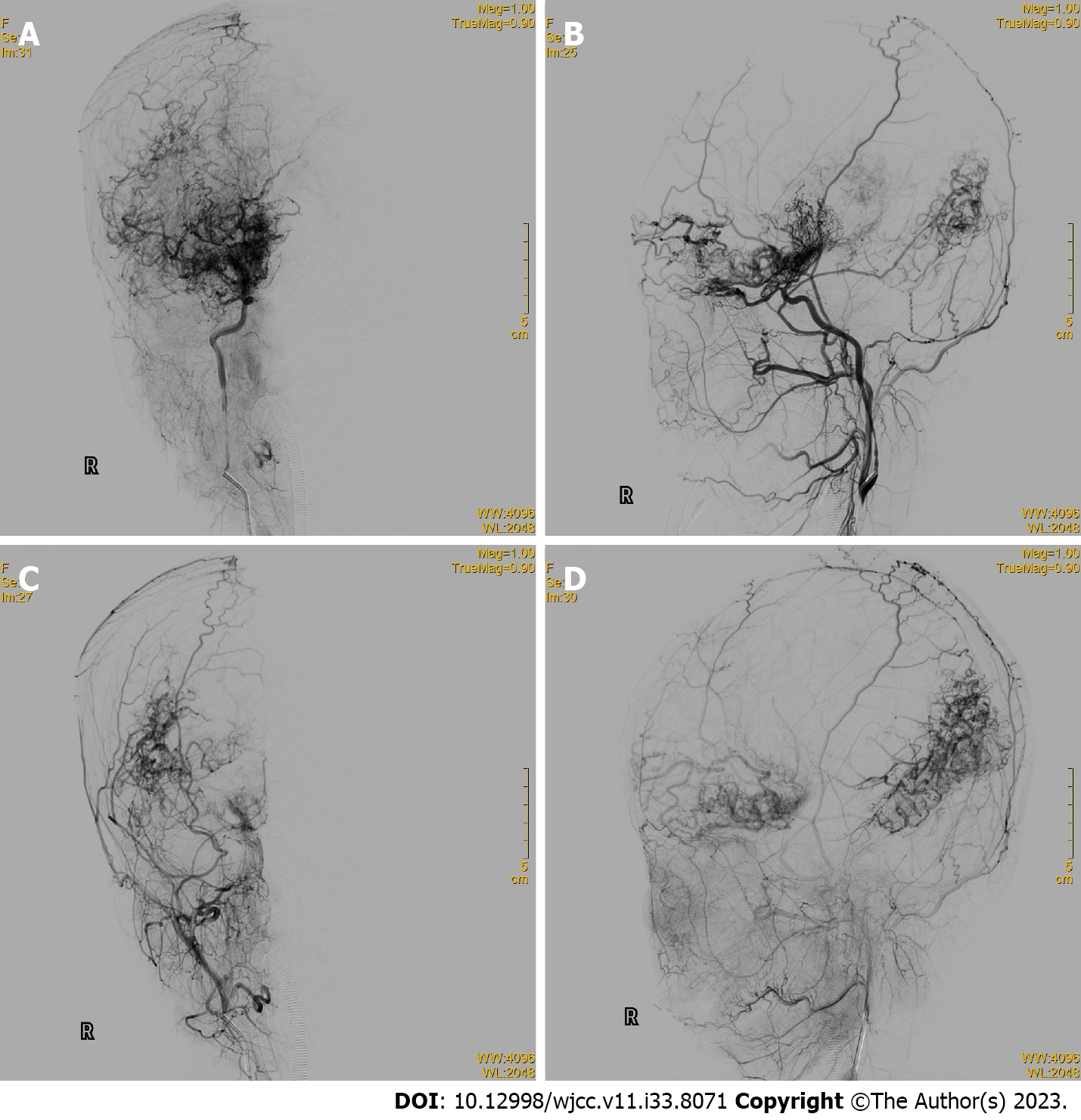

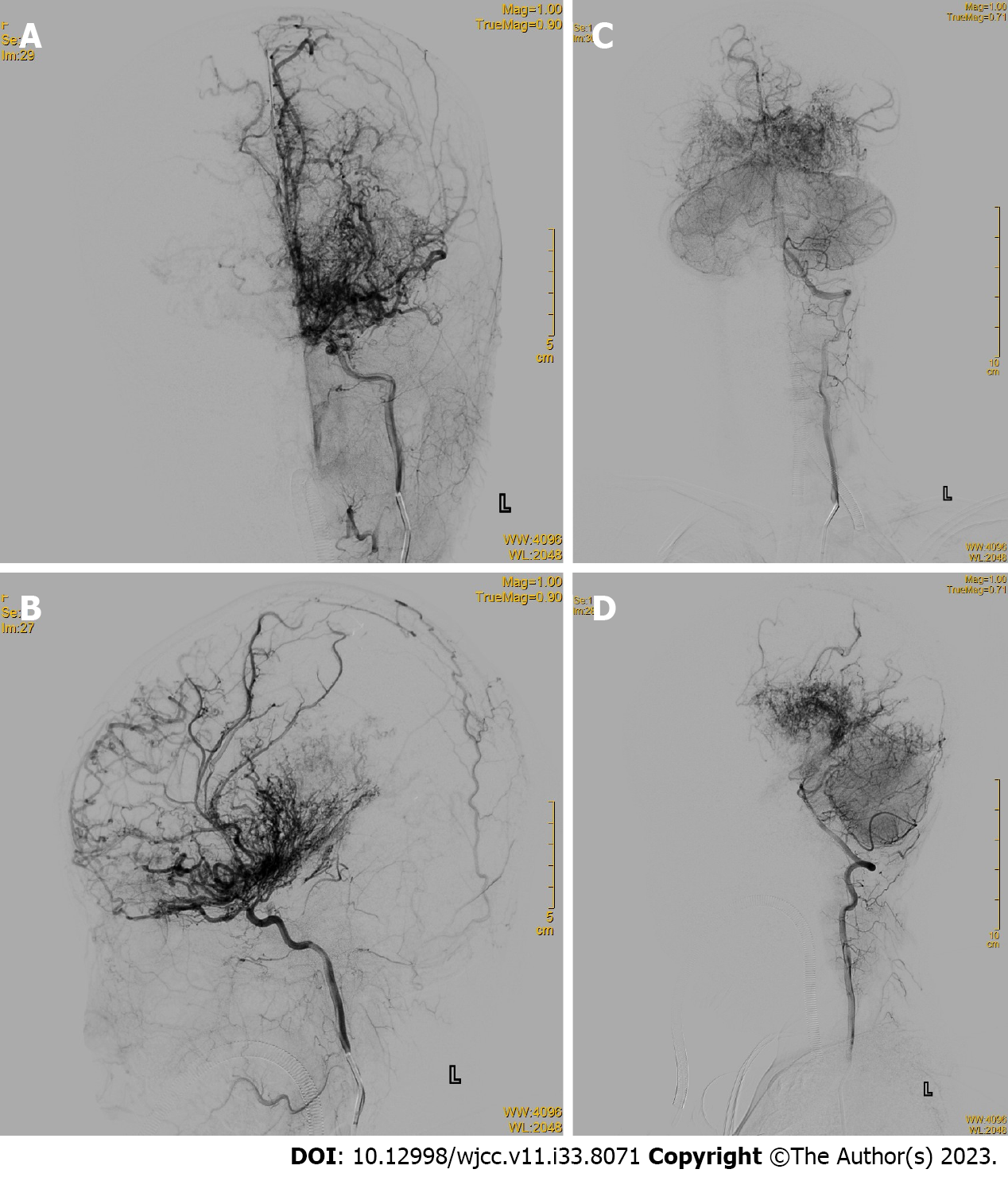

MRI and MRA examinations of the head detected softening foci in the left frontal and parietal lobes and the right parietal lobe. The examinations also revealed localized stenosis of the C2 segment of the left internal carotid artery; bilateral stenosis of the beginning of the middle cerebral artery; segmental stenosis of the M1 segment, small distal middle cerebral artery and branches; thickened and tortuous adjacent meningeal vessels; an unclear lumen at the beginning of the bilateral anterior cerebral artery; and multiple thickened and tortuous surrounding vascular networks (Figure 1).

Cerebral digital subtraction angiography (DSA) showed occlusions in the internal carotid arteries from the posterior communicating artery to the far side of the brain, numerous anomalous hyperplastic capillaries in the area supplied by the internal carotid arteries and the posterior cerebral arteries bilaterally, and several branches of the external carotid arteries and dural vessels supplying blood to the intracranial area (Figures 2 and 3).

The final diagnosis was pediatric CPA.

The child showed no obvious signs of intracranial hemorrhage or infarction on imaging examinations for mild neurological symptoms. Cerebral DSA showed clear CPA features. Because of this diagnosis and presentation, no specific treatment was provided; only conservative treatment with sedation, fluid replacement, and blood anticoagulation was administered after the cerebral DSA angiography procedure. The patient could not cooperate with the follow-up MRI examination because of her young age. The patient’s family declined further treatment and decided to discharge her because of the surgery’s high risk.

The child was followed up for 3 mo; no further worsening of symptoms was observed.

Lasjaunias et al[1] reported case data from 1434 patients with AVM; 49 (3.4%) were screened for CPA in a retrospective study. CPA episodes are predominant in young adult women[1]. This study collected and summarized the clinical, epidemiological, and prognostic follow-up data of pediatric CPA. Includes not only new cases within the last 5 years[3-8] but also older cases[9-18]. The review literature reported 21 pediatric CPA cases, with a mean patient age of 10.4 years and an age range of 2–18 years. Of these 21 children, excluding one case where the authors did not specify the sex, 11 (55%) were female, and 9 (45%) were male, consistent with Lasjaunias’s findings. Cerebral hemorrhage was usually the primary presentation in classic pediatric AVM (70%, n = 100)[19]; headache (57%), epilepsy (29%), and limb weakness (24%) were more common in pediatric CPA. Although hemorrhage is rare, the risk of rebleeding is high[20]. In our case, the patient did not experience significant headache or seizure symptoms and had only occasional slurred speech and limb weakness.

CPA is diagnosed based on typical imaging features. Its morphology differs from typical AVMs: MRI shows multiple large vessels entangled and interspersed with brain parenchyma; computed tomography shows a heterogeneous lesion with a densely enhanced vascular meshwork, frequently involving one or more lobes. MRI sequences showed a flowing void effect within the lesion and diffuse enhancement on T1 sequences. DSA imaging revealed a diffusely proliferating capillary network with rapid blood flow, frequent epidural blood supply, and multiple narrowing of the supplying arteries[15]. CPA is characterized by the absence of thick blood-supplying arteries and draining veins, interspersed with brain parenchyma, neurons in the vascular network, and aneurysms in the blood-supplying arteries[7,18]. Vascular lesions in the CPA are unstable; some patients have imaging findings that suggest continued lesion growth[18].

Traditional AVM treatments involve mostly resection, endovascular embolization, or radiation therapy[21]. Pediatric patients with CPA present with headache as the main manifestation; ischemic symptoms manifest more commonly than hemorrhages. Any surgical, interventional, or radiological treatment of pediatric CPA may worsen symptoms because of normal nerve tissue in the vascular network of CPA lesions. In pediatric patients with CPA, conservative treatment aimed at symptom control is preferred, including anticoagulation, antithrombotic, and antiepileptic medications. These treatments are effective in controlling the symptoms of most patients; however, some patients have subsequent cerebral hemorrhaging due to the continued lesion growth[3]. Gamma knife[22] and endovascular embolization[23] relieve headaches effectively in patients with CPA, which is difficult to control medically; however, these treatments are less effective for other symptoms of neurological dysfunction, including slurred speech and hemiparesis. Surgical resection has been an option for treating CPA since 2021, when Choi et al[6] reported the first successful surgical resection of a CPA lesion despite its extreme risks. Ochoa et al[4] in 2022 performed surgical resection on two patients with pediatric CPA. Patients were free of significant recurrence at 3–6 years of follow-up. Other surgical procedures, such as indirect revascularization, have also been proven effective. Kimiwada et al[8] and Ellis et al[16] used an indirect revascularization procedure to improve patients’ symptoms; no worsening of symptoms at a minimum 1-year follow-up was reported.

CPA’s pathophysiological type differs from AVM because of its specific vascular configuration. Vargas et al[15] demonstrated that patients with CPA have significantly longer mean capillary passage times and multiple segmental arterial stenoses, leading to reduced perfusion of the surrounding brain tissue. Marks et al[23] reported a patient with CPA having high levels of vascular endothelial growth factor, thrombin reactive protein, and fibroblast growth factor in the cerebrospinal fluid. This finding suggests CPA may be the body’s overreaction to unexplained ischemia, ultimately leading to the proliferation of vascular endothelial cells followed by uncontrolled vascular proliferation. Because CPA and Moyamoya disease have relatively similar pathophysiological mechanisms, they might be confused in clinical diagnosis. However, no direct comparison exists in the literature; further research is required.

CPA is a rare ischemic cerebrovascular disease with a much lower incidence in the pediatric population. Most pediatric cases have headaches as the main clinical manifestation; patients achieve good outcomes through medical treatment and observation. Since CPA was introduced as a separate disease category in 2008, research into its pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment has advanced; however, the treatment still has no definitive consensus. More high-quality research is required to support the existing studies in developing evidence-based treatment guidelines for CPA.

| 1. | Lasjaunias PL, Landrieu P, Rodesch G, Alvarez H, Ozanne A, Holmin S, Zhao WY, Geibprasert S, Ducreux D, Krings T. Cerebral proliferative angiopathy: clinical and angiographic description of an entity different from cerebral AVMs. Stroke. 2008;39:878-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chin LS, Raffel C, Gonzalez-Gomez I, Giannotta SL, McComb JG. Diffuse arteriovenous malformations: a clinical, radiological, and pathological description. Neurosurgery. 1992;31:863-8; discussion 868. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Saito T, Harada K, Kajihara M, Sanbongi C, Fukuyama K. Long-term hemodynamic changes in cerebral proliferative angiopathy presenting with intracranial hemorrhage: illustrative case. J Neurosurg Case Lessons. 2023;5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ochoa A, Mantese B, Requejo F. Hemorrhagic cerebral proliferative angiopathy in two pediatric patients: case reports. Childs Nerv Syst. 2022;38:789-794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rebello A, Ahuja CK, Aleti S, Singh R. Cerebral proliferative angiopathy: a rare cause of stroke and seizures in young. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Choi GY, Choi HJ, Jeon JP, Yang JS, Kang SH, Cho YJ. Removal of malformation in cerebral proliferative angiopathy: illustrative case. J Neurosurg Case Lessons. 2021;1:CASE2095. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Beniwal M, Kandregula S, Aravind, Rao KVLN, Vikas V, Srinivas D. Pediatric cerebral proliferative angiopathy presenting infratentorial hemorrhage. Childs Nerv Syst. 2020;36:429-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kimiwada T, Hayashi T, Takahashi M, Shirane R, Tominaga T. Progressive Cerebral Ischemia and Intracerebral Hemorrhage after Indirect Revascularization for a Patient with Cerebral Proliferative Angiopathy. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2019;28:853-858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Maekawa H, Terada A, Ishiguro T, Komiyama M, Lenck S, Renieri L, Krings T. Recurrent periventricular hemorrhage in cerebral proliferative angiopathy: Case report. Interv Neuroradiol. 2018;24:713-717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zheng WJ. [Experimental study on the treatment of spinal cord injury with transplantation of the greater omentum]. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 1989;27:93-95, 125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Srivastava T, Mathur T, Jain R, Sannegowda RB. Cerebral proliferative angiopathy: A rare clinical entity with peculiar angiographic features. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2013;16:674-675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kimiwada T, Hayashi T, Shirane R, Tominaga T. 123I-IMP-SPECT in a patient with cerebral proliferative angiopathy: a case report. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22:1432-1435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Khan A, Rattihalli R, Beri S, Dickinson F, Hussain N, Gosalakkal J. Cerebral proliferative angiopathy: a rare form of vascular malformation. J Paediatr Child Health. 2013;49:504-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gold JJ, Crawford JR. Acute hemiparesis in a child as a presenting symptom of hemispheric cerebral proliferative angiopathy. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2013;2013:920859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Vargas MC, Castillo M. Magnetic resonance perfusion imaging in proliferative cerebral angiopathy. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2011;35:33-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ellis MJ, Armstrong D, Dirks PB. Large vascular malformation in a child presenting with vascular steal phenomenon managed with pial synangiosis. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2011;7:15-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Fierstra J, Spieth S, Tran L, Conklin J, Tymianski M, ter Brugge KG, Fisher JA, Mikulis DJ, Krings T. Severely impaired cerebrovascular reserve in patients with cerebral proliferative angiopathy. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2011;8:310-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Liu P, Lv X, Lv M, Li Y. Cerebral proliferative angiopathy: Clinical, angiographic features and literature review. Interv Neuroradiol. 2016;22:101-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Nicolato A, Longhi M, Tommasi N, Ricciardi GK, Spinelli R, Foroni RI, Zivelonghi E, Zironi S, Dall'Oglio S, Beltramello A, Meglio M. Leksell Gamma Knife for pediatric and adolescent cerebral arteriovenous malformations: results of 100 cases followed up for at least 36 mo. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2015;16:736-747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Yamaki VN, Solla DJF, Telles JPM, Liem GLJ, da Silva SA, Caldas JGMP, Teixeira MJ, Paschoal EHA, Figueiredo EG. The current clinical picture of cerebral proliferative angiopathy: systematic review. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2020;162:1727-1733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zyck S, Davidson CL, Sampath R. Arteriovenous Malformations. 2022 Aug 15. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Hong KS, Lee JI, Hong SC. Neurological picture. Cerebral proliferative angiopathy associated with haemangioma of the face and tongue. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81:36-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Marks MP, Steinberg GK. Cerebral proliferative angiopathy. J Neurointerv Surg. 2012;4:e25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Neuroimaging

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Pavlovic M, Serbia S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH