Published online Nov 6, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i31.7712

Peer-review started: September 13, 2023

First decision: September 14, 2023

Revised: September 21, 2023

Accepted: October 26, 2023

Article in press: October 26, 2023

Published online: November 6, 2023

Processing time: 54 Days and 2.9 Hours

Intracranial fusiform aneurysms are rare, spindle-shaped, and nonsaccular arterial dilatations that may be caused by dissection.

A 48-year-old man complained of wake-up onset of dysarthria and left-sided weakness. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of the brain revealed an infarction in the territories of the right middle and posterior cerebral arteries. Computed tomography angiography showed fusiform aneurysms in the right vertebral artery and bilateral petrous segments of the internal carotid arteries (ICAs). Despite conservative management, malignant ischemic stroke recurred in the contralateral ICA territory within a day of the onset of the index stroke.

We report a rare case of successive malignant strokes in a patient with multiple fusiform aneurysms. Herein, we emphasize that clinicians should consider aggressive treatment for patients with ischemic stroke and multiple fusiform aneurysms.

Core Tip: Intracranial fusiform aneurysms are spindle-shaped and nonsaccular arterial dilatations. Dissection is the most common cause of fusiform aneurysms. Intracranial dissection is an important cause of ischemic stroke, especially in young patients at low risk for atherosclerosis. The treatment of intracranial fusiform aneurysms is still under debate; however, clinicians should consider aggressive treatment in patients with ischemic stroke with multiple fusiform aneurysms.

- Citation: Shin DS, Yeo DK, Choi EJ. Successive development of ischemic malignant strokes in a patient with multiple fusiform aneurysms: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(31): 7712-7717

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i31/7712.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i31.7712

Intracranial fusiform aneurysms are rare, spindle-shaped, and nonsaccular arterial dilatations, accounting for 3%-13% of intracranial aneurysms[1,2]. They may be caused by dissection, which refers to rupture and bleeding within the arterial wall layers[1]. These aneurysms are typically discovered in patients undergoing investigations for stroke; thrombosis is a known cause of ischemic stroke[2]. Multiple fusiform aneurysms in a patient are uncommon, as is the recurrence of stroke in different vascular territories within 1 day of the initial stroke[3,4]. We present an unusual case of successive malignant strokes in a patient with multiple fusiform aneurysms.

A 48-year-old man with a chronic history of smoking and alcohol use complained of wake-up onset dysarthria and left-sided weakness.

Seven hours after stroke onset, the patient visited the emergency department. He stated that he had recently suffered a traumatic head injury but did not complain of headaches.

He had no other past medical history.

He had no family history of cerebrovascular disease.

The patient was alert and oriented, and his vital signs were stable. A neurological examination revealed left-sided facial palsy and hemiparesis (Medical Research Council grade 4/5).

Laboratory examination demonstrated elevated white blood cell count (11.64 10³/μL; normal range 4.0-11.0) and homocysteine (27.42 µmol/L; normal range 5.08-15.39). His erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein level, chest X-ray, and electrocardiogram findings were unremarkable.

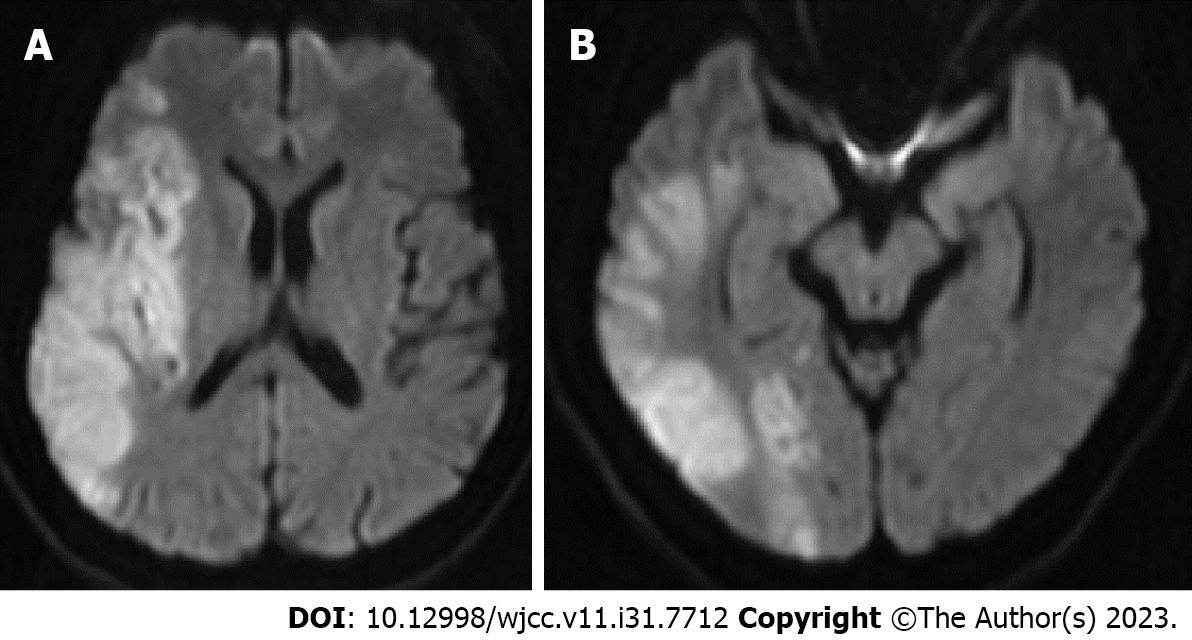

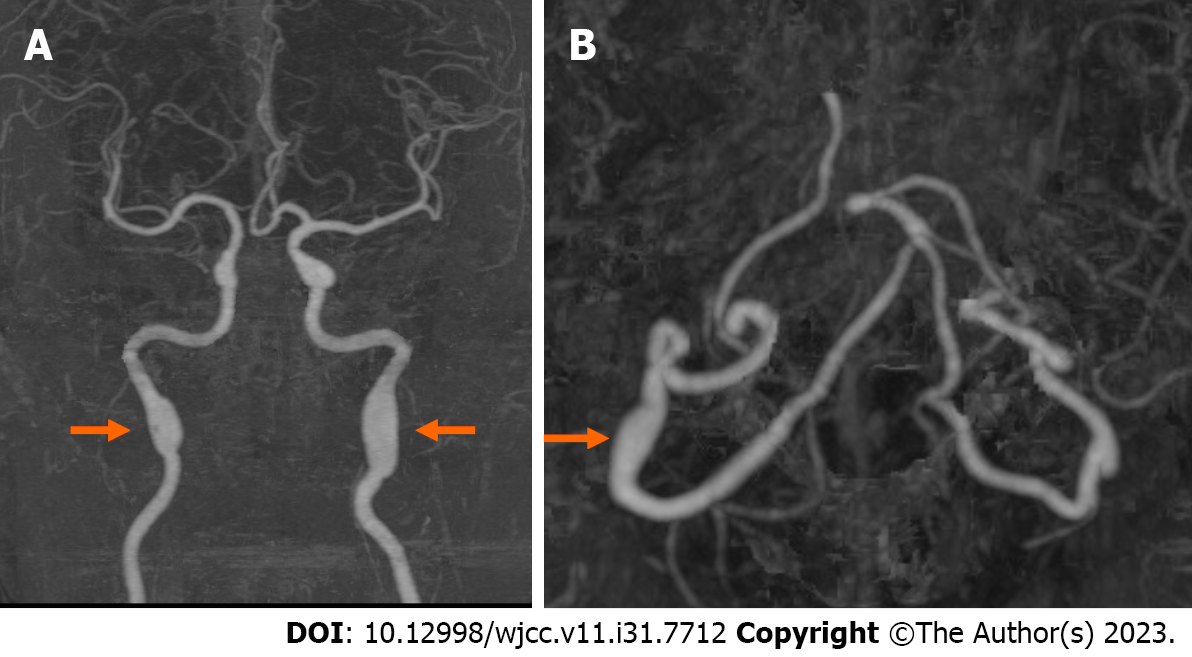

Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain revealed high-signal intensity lesions in the territories of the right middle cerebral artery (MCA) and some of the posterior cerebral arteries (Figure 1). Brain computed tomography angiography (CTA) revealed bilateral fusiform aneurysms in the petrous segment of the internal carotid artery (ICA) bilaterally and in the third segment of the right vertebral artery (Figure 2).

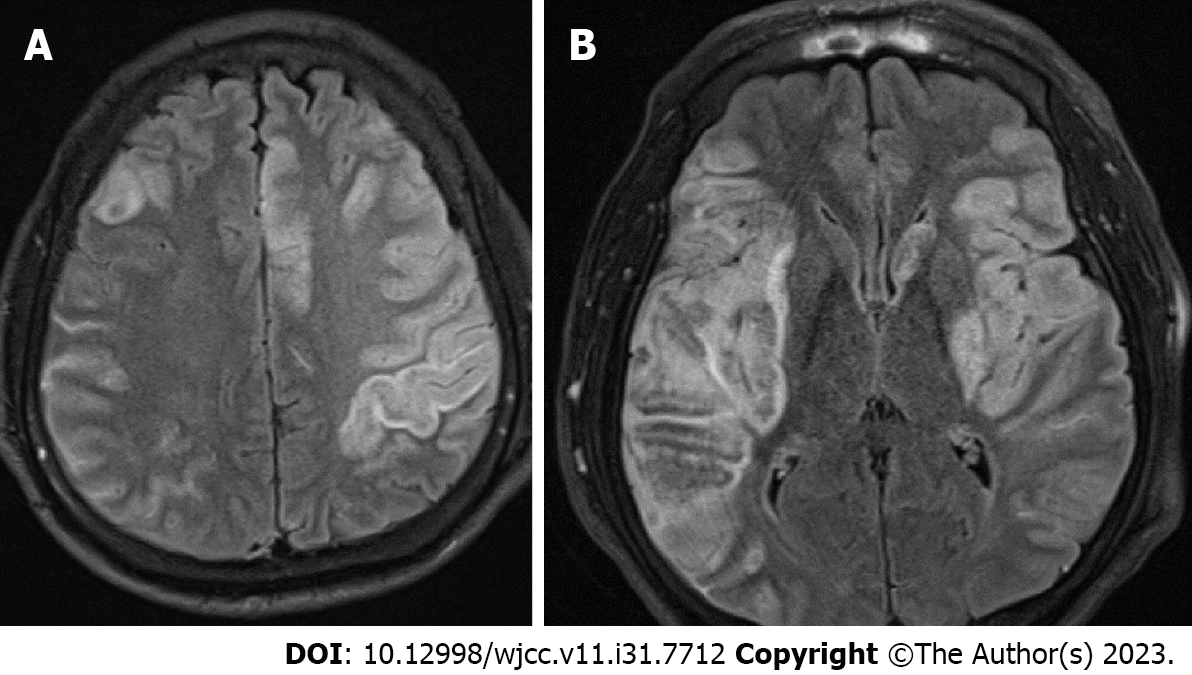

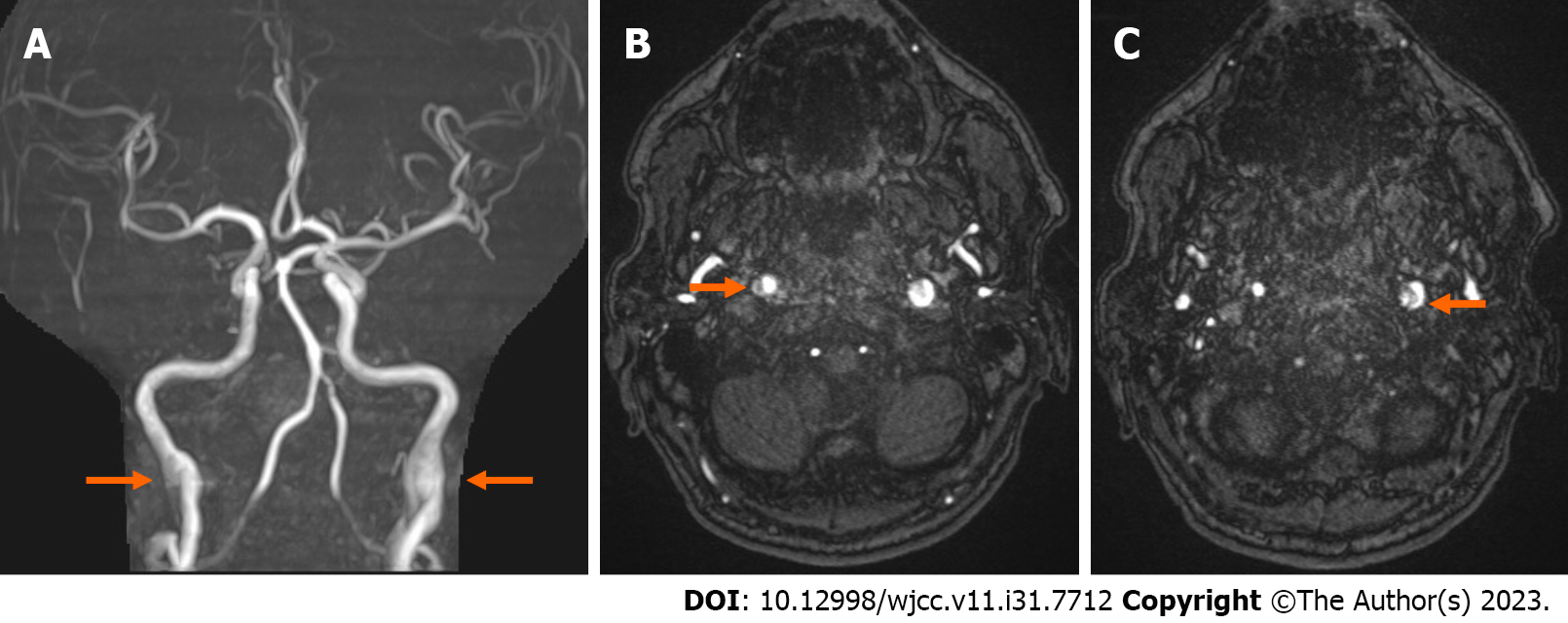

The patient was prescribed 300 mg aspirin and 40 mg atorvastatin and was admitted to the hospital. Approximately 5 h after presenting to the emergency department, he suffered from a generalized tonic-clonic seizure. His seizures resolved after the administration of intravenous lorazepam. He was semi-comatose and his right-sided extremity was weaker than his left extremity. Brain CT did not show signs of hemorrhage; MRI showed a new ischemic lesion in the territories of the left anterior cerebral artery and left MCA, in addition to the hemorrhagic transformed index right-sided lesions (Figure 3). Non-contrast magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) revealed fusiform aneurysms and a double-lumen appearance of the bilateral petrous ICAs (Figure 4). The proximal ICAs were unremarkable. Subsequent tests revealed elevated IgM anticardiolipin antibody (29.0 CU; normal range ≤ 20) and IgM anti-beta-2 glycoprotein I (23.5 CU; normal range < 20), and decreased antithrombin III (51%; normal range 75-125) and protein C (63%; normal range 73-142). The following investigations were unremarkable: transthoracic echocardiography, Holter monitoring, glycated hemoglobin, low-density lipoprotein, alpha-1 antitrypsin, protein S, and lupus anticoagulant.

The patient was diagnosed with malignant infarction in both cerebral hemispheres with multiple arterial dissections.

The patient received conservative treatment, including aspirin and statin.

A follow-up computed tomography showed cerebral edema. The patient died 5 d after symptom onset.

Fusiform is a morphological term that does not reflect the etiology of this type of aneurysm[1]. The known causes of fusiform aneurysms include dissection and atherosclerosis, the most common of which is dissection[1]. Arterial dissection involves the formation of an intramural hematoma caused by intimal tearing of intracranial vessels[5]. If the intramural hemorrhage extends into the subadventitial plane, a sac-like pouch, called a dissecting aneurysm, is formed[5]. Intracranial dissection is an important cause of ischemic stroke, especially in young patients with a low atherosclerosis risk[6]. An intramural hematoma is formed by an intimal tear in an intracranial vessel, which can narrow the vessel lumen[7]. A complete stroke occurs when the intramural clot expands enough to lead to vessel occlusion or if the vessel wall ruptures and releases the clot into the lumen, leading to distal embolization[7]. In this patient, the index ischemic malignant stroke resulted in hemorrhagic transformation, as revealed by the follow-up imaging results. The ICA appeared recanalized after an intramural clot initially occluded the lumen.

Although digital subtraction angiography is regarded as the gold standard for diagnosing dissection, noninvasive methods, such as CTA and MRA, are also widely used. An important diagnostic finding was the double-lumen appearance, showing the false and true lumens divided by an intimal flap, which was found in the ICA of this patient bilaterally[8]. This finding was not observed in the right VA, which showed a fusiform aneurysm on CTA, presumably due to the small caliber of the vertebral artery[8].

Multiple arterial dissections commonly involve the posterior circulation and rarely the bilateral ICAs[9]. Béjot et al[10] reported that multiple cervical artery dissections are likely to be associated with environmental triggers, such as recent infection, cervical manipulation, and head surgery. The patient had a history of recent head trauma, and his increased white blood cell suggested the possibility of a recent infection. Hyperhomocysteinemia has also been postulated as a risk factor for dissection[11]. Homocysteine causes the premature breakdown of arterial elastic fibers, and irreversible homocysteinylation leads to cumulative damage and neurological symptoms[11]. Hematological disorders are another commonly unrecognized cause of both acute stroke of unusual etiology and malignant ischemic stroke[12]. Iseki et al[13] reported cases of cerebral artery dissection secondary to antiphospholipid syndrome and suggested that the interaction between antiphospholipid antibodies and endothelial cells may contribute to dissection development. Persistently elevated titers of antiphospholipid antibodies, including anticardiolipin and anti-beta-2 glycoprotein I, at least 12 wk apart, are essential for the diagnosis of antiphospholipid syndrome; however, follow-up examinations were not available for our patient.

The treatment of intracranial fusiform aneurysms remains controversial. Day et al[7] recommended conservative management for most cases of small and for some cases of large asymptomatic focal dilatations. Additionally, conservative treatment has been advocated as effective for patients with stenotic or occlusive lesions and acute ischemic symptoms. However, poor outcomes after conservative treatment have been reported. Béjot et al[10] reported that 12.0% of 145 patients with multiple cervical artery dissections sustained moderate to severe disabilities. Guo et al[14] reported that large or symptomatic intracranial fusiform aneurysms are associated with increased mortality and suggested surgery and endovascular treatment as effective options for selected cases.

This case report had several limitations. First, a digital subtraction angiography was not performed. Second, the mechanisms of dissection, such as connective tissue disease, have not been sufficiently evaluated.

Here, we report a rare case of successive malignant strokes with multiple fusiform aneurysms. Our patient showed devastating outcomes despite conservative treatment. This case emphasizes that aggressive treatment should be considered for patients with ischemic stroke and multiple fusiform aneurysms. Future studies on treatment strategies based on the pathophysiology and risk profiles of multiple fusiform aneurysms are needed.

The authors thank Mr. Lee DG, majoring in family medicine at the University of British Columbia. He has contributed to improvements in the English writing.

| 1. | Park SH, Yim MB, Lee CY, Kim E, Son EI. Intracranial Fusiform Aneurysms: It's Pathogenesis, Clinical Characteristics and Managements. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2008;44:116-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | al-Yamany M, Ross IB. Giant fusiform aneurysm of the middle cerebral artery: successful Hunterian ligation without distal bypass. Br J Neurosurg. 1998;12:572-575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Matsushige T, Kiya K, Satoh H, Mizoue T, Kagawa K, Araki H. Multiple spontaneous dissecting aneurysms of the anterior cerebral and vertebral arteries. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2005;45:259-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Das S, Valyi-Nagy T. Multiple cerebral fusiform aneurysms involving the posterior and anterior circulation including the anterior cerebral artery: a case report. Folia Neuropathol. 2017;55:73-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Biondi A. Trunkal intracranial aneurysms: dissecting and fusiform aneurysms. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2006;16:453-465, viii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Debette S, Compter A, Labeyrie MA, Uyttenboogaart M, Metso TM, Majersik JJ, Goeggel-Simonetti B, Engelter ST, Pezzini A, Bijlenga P, Southerland AM, Naggara O, Béjot Y, Cole JW, Ducros A, Giacalone G, Schilling S, Reiner P, Sarikaya H, Welleweerd JC, Kappelle LJ, de Borst GJ, Bonati LH, Jung S, Thijs V, Martin JJ, Brandt T, Grond-Ginsbach C, Kloss M, Mizutani T, Minematsu K, Meschia JF, Pereira VM, Bersano A, Touzé E, Lyrer PA, Leys D, Chabriat H, Markus HS, Worrall BB, Chabrier S, Baumgartner R, Stapf C, Tatlisumak T, Arnold M, Bousser MG. Epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of intracranial artery dissection. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:640-654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 248] [Cited by in RCA: 322] [Article Influence: 29.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Day AL, Gaposchkin CG, Yu CJ, Rivet DJ, Dacey RG Jr. Spontaneous fusiform middle cerebral artery aneurysms: characteristics and a proposed mechanism of formation. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:228-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mehdi E, Aralasmak A, Toprak H, Yıldız S, Kurtcan S, Kolukisa M, Asıl T, Alkan A. Craniocervical Dissections: Radiologic Findings, Pitfalls, Mimicking Diseases: A Pictorial Review. Curr Med Imaging Rev. 2018;14:207-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hassan AE, Zacharatos H, Mohammad YM, Tariq N, Vazquez G, Rodriguez GJ, Suri MF, Qureshi AI. Comparison of single versus multiple spontaneous extra- and/or intracranial arterial dissection. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22:42-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Béjot Y, Aboa-Eboulé C, Debette S, Pezzini A, Tatlisumak T, Engelter S, Grond-Ginsbach C, Touzé E, Sessa M, Metso T, Metso A, Kloss M, Caso V, Dallongeville J, Lyrer P, Leys D, Giroud M, Pandolfo M, Abboud S; CADISP Group. Characteristics and outcomes of patients with multiple cervical artery dissection. Stroke. 2014;45:37-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Takagi H, Umemoto T. Homocysteinemia is a risk factor for aortic dissection. Med Hypotheses. 2005;64:1007-1010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Arboix A, Jiménez C, Massons J, Parra O, Besses C. Hematological disorders: a commonly unrecognized cause of acute stroke. Expert Rev Hematol. 2016;9:891-901. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Iseki T, Yamashita Y, Ueno Y, Hira K, Miyamoto N, Yamashiro K, Tsunemi T, Teranishi K, Yatomi K, Nakajima S, Kijima C, Oishi H, Hattori N. Cerebral artery dissection secondary to antiphospholipid syndrome: A report of two cases and a literature review. Lupus. 2021;30:118-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Guo Y, Song Y, Hou K, Yu J. Intracranial Fusiform and Circumferential Aneurysms of the Main Trunk: Therapeutic Dilemmas and Prospects. Front Neurol. 2021;12:679134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Clinical neurology

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Arboix A, Spain S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yan JP