Published online Sep 16, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i26.6274

Peer-review started: June 6, 2023

First decision: July 17, 2023

Revised: August 8, 2023

Accepted: August 17, 2023

Article in press: August 17, 2023

Published online: September 16, 2023

Processing time: 93 Days and 20.3 Hours

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is an acute autoimmune-mediated poly

A 68-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital with weakness of the limb for more than 3 d. Additional symptoms included neck pain, progressive numbness in the distal extremities, urinary and fecal retention, and reduced perception of temperature. She was diagnosed with an anti-sulfatide antibody-positive GBS variant and discharged after treatment with methylprednisolone and intravenous human immunoglobulin pulse therapy. Unlike common cases of anti-sulfatide antibody-positive GBS, this patient had atypical clinical symptoms of spinal cord involvement. No similar cases have previously been reported in China.

Although GBS is associated with a poor prognosis, a prompt diagnosis allows early administration of combined intravenous human immunoglobulin and methylprednisolone pulse therapy.

Core Tip: Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is an autoimmune-mediated acute polyneurogenic neuropathy. The clinical presentation of GBS is characterized by an acute onset, symmetric limb weakness, sensory disturbances, extraocular muscle paralysis, ataxia, diminished tendon reflexes, hypotonia, abdominal distention, constipation, and urinary retention following autonomic nerve damage. In recent years, anti-sulfatide antibody positivity has been increasingly noted in GBS cases, with varying clinical symptoms; thus, these antibodies have become crucial for the diagnosis of GBS. Here, we report the case of a patient who presented with signs and symptoms of spinal cord involvement and was diagnosed with anti-sulfatide antibody-positive GBS combined with spinal cord involvement, which is relatively rare in clinical practice; the symptoms improved after receiving combined treatment with intravenous human immunoglobulin and methylprednisolone pulse therapy.

- Citation: Liu H, Lv HG, Zhang R. Variant of Guillain-Barré syndrome with anti-sulfatide antibody positivity and spinal cord involvement: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(26): 6274-6279

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i26/6274.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i26.6274

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is an acute autoimmune-mediated polyneuropathy manifested by motor axonal neuropathy, motor sensory axonal neuropathy, Miller-Fisher syndrome, pan-autonomic neuropathy, and sensory neuropathy[1]. It is usually caused by an immune response after infection by Campylobacter jejuni, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, or the Influenza A virus. The antibodies from infection can cross-react with gangliosides on the surface of nerve cell membranes, leading to nerve damage and blocking of nerve conduction[1]. Recent evidence has revealed that infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 can also cause GBS[2]. Patients with GBS often present with acute onset of symmetric limb weakness, sensory disturbances, extraocular muscle paralysis, ataxia, weak tendon reflexes, low muscle tone, abdominal distention, constipation and urinary retention caused by autonomic nerve damage. Lesions are commonly observed in nerve roots, ganglia, peripheral nerves, and occasionally in the spinal cord. The main pathological changes include edema, congestion, varying degrees of lymphocyte and mononuclear macrophage infiltration, segmental demyelination, and axonal degeneration[3].

Anti-sulfatide antibodies may be associated with the pathogenesis of GBS and can be used for the early diagnosis of polyneuropathy[4,5]. Pestronk et al[6] first suggested in 1991 that anti-sulfatide antibodies were associated with polyneuropathy and inflammation. An increased level of anti-sulfatide antibodies can cause demyelination, possibly because they bind to myelin on the surface of Schwann cells and activate the complement cascade, which may be responsible for peripheral nerve injury[7]. A case report of a man with GBS and end-stage AIDS found with a high level of anti-thiolipid immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies and a reduced level of CD4+ T lymphocytes suggested that autoantibody abnormalities may contribute to the pathogenesis of GBS[8]. A retrospective analysis of 25 neuropathy patients showed that an elevated level of anti-sulfatide antibodies was associated with specific subtypes or variants of peripheral neuropathy, primarily due to damage to the sensory or sensorimotor axons and, to a lesser extent, damage to small or mixed fibers of the sensory component[9]. These findings provide a theoretical basis for the interpretation that the combination of spinal cord involvement and anti-sulfatide antibodies can contribute to the pathogenesis of GBS.

Anti-sulfatide antibodies can occur in many patients with GBS and other diseases[10]. The purpose of this case report was to present the co-occurrence of anti-sulfatide antibody positivity with spinal cord involvement in patients with GBS. Specifically, we describe a patient who presented with signs and symptoms of spinal cord pathology and was ultimately diagnosed with anti-sulfatide antibody-positive GBS. This clinical finding is relatively rare, and the case demonstrates the resolution of symptoms after treatment.

A 68-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital for weakness for more than 3 d.

Three days before admission, she first experienced weakness of the limb weakness with posterior neck pain, numbness in the distal extremities, and a feeling of electric shock when touched. On the day of admission, these symptoms were aggravated, and she could not stably hold things in either hand. She also had cold-related pain in the upper extremities, weakness in the lower extremities, an inability to ambulate, urinary and fecal retention, and increased posterior neck pain. A cranial computed tomography (CT) showed no obvious signs of hemorrhage. The patient did not experience chills or fever, cough or sputum production, headache, visual hallucination, choking and coughing when eating, dysarthria, chest pain, palpitations, abdominal distension, or diarrhea.

She had a history of hypertension for more than one year and was taking daily amlodipine tablets. She denied any history of upper respiratory tract infection, diarrhea, or abdominal pain before the onset of symptoms and reported no recent vaccinations. She had no history of diabetes mellitus or allergy to foods or drugs.

She had no history of diabetes mellitus or allergy to foods or drugs. Denial of family history.

Physical examination: At admission, her body temperature was 36.8 ℃, her pulse rate was 76 beats/min and rhythmical, and there were no pathological murmurs in the auscultation area of each heart valve. Her respiratory rate was 20 breaths/min, her blood pressure was 145/78 mmHg, and there was no neck stiffness or breathing resistance. There were clear breath sounds in both lungs and no dry rales. Her abdomen was soft, and she had no varices in the veins of the abdominal wall. No pressure tenderness or rebound pain was observed at McBurney's point. There was no shifting dullness to percussion, but slightly reduced bowel sounds (2–3/min) were observed. Her lower limbs had no edema.

Neurological examination: The patient had clear consciousness and no dysarthria. Her pupils were round, had the same diameter (3.0 mm), and were light-sensitive. She had adequate eye movement in all directions, no nystagmus, and symmetrical bilateral frontal lines. The muscle strength of both upper limbs was grade 4; the muscle strength of both lower limbs was grade 3; the muscle tone of the limbs was low; and the tendon reflexes had bilateral weakness. The Babinski sign was positive on both sides. Her sensations of bilateral distal pain and temperature were slightly reduced; the two-handed finger-nose test was stable and accurate; the bilateral heel-knee-shin test was unstable and inaccurate; and she had normal bilateral vibration sensation and joint position sensation. The meningeal stimulation sign was negative, and she exhibited no involuntary movements.

The complete blood count, liver and renal function tests, coagulation indicators, and tumor indicators indicated no significant abnormalities and cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) also did not show significant abnormalities. A lumbar puncture indicated an elevated cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure of 116 mmH20 and the presence of cytoalbuminologic dissociation. A peripheral neuropathy immunoblotting test (ganglioside antibody profile) was positive for anti-sulfatide antibody IgG. The markers of central nervous system demyelinating diseases, including oligoclonal bands, aquaporin 4, and anti-MOG antibodies, were all negative

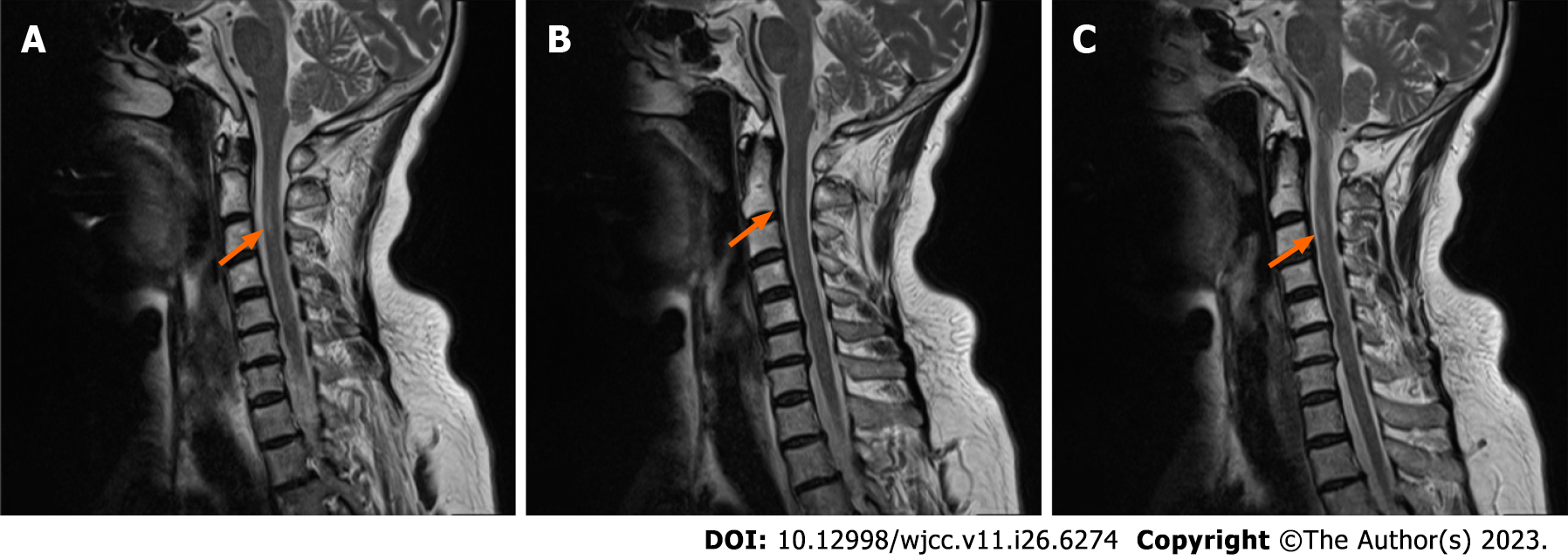

Electromyography revealed some motor nerves with conduction block but normal sensory nerve conduction velocity and wave amplitude, suggesting damage to multiple peripheral nerves. A cervical MRI revealed a high signal in the cervical spinal cord, suggesting inflammatory changes.However, a thoracic MRI revealed degeneration of certain thoracic discs, and a lumbar MRI revealed bulges of the L3/4, L4/5, and L5/S1 discs. A chest CT revealed two foci of lung fibrosis, but a whole abdominal CT did not reveal significant abnormalities

The final diagnosis was Variant of GBS with anti-sulfatide antibody positivity and spinal cord involvement.

The patient had a self-retaining urinary catheter to treat urinary retention, anal irrigation with glycerol to treat fecal retention, and mecobalamin tablets (0.5 mg, thrice daily) for treatment of GBS symptoms. She also received intravenous infusion therapy with human immunoglobulin (0.4 g/kg body weight/d) and methylprednisolone (500 mg/d dissolved in 500 mL of sodium chloride after static dosing). After three days, the methylprednisolone dose was reduced to 240 mg, and after another three days, it was reduced to 120 mg. Then, prednisone acetate tablets (60 mg/d) were administered, and the daily dose was reduced by 10 mg per week. Prednisone acetate was discontinued after one month, when potassium, calcium, and gastric protection were provided.

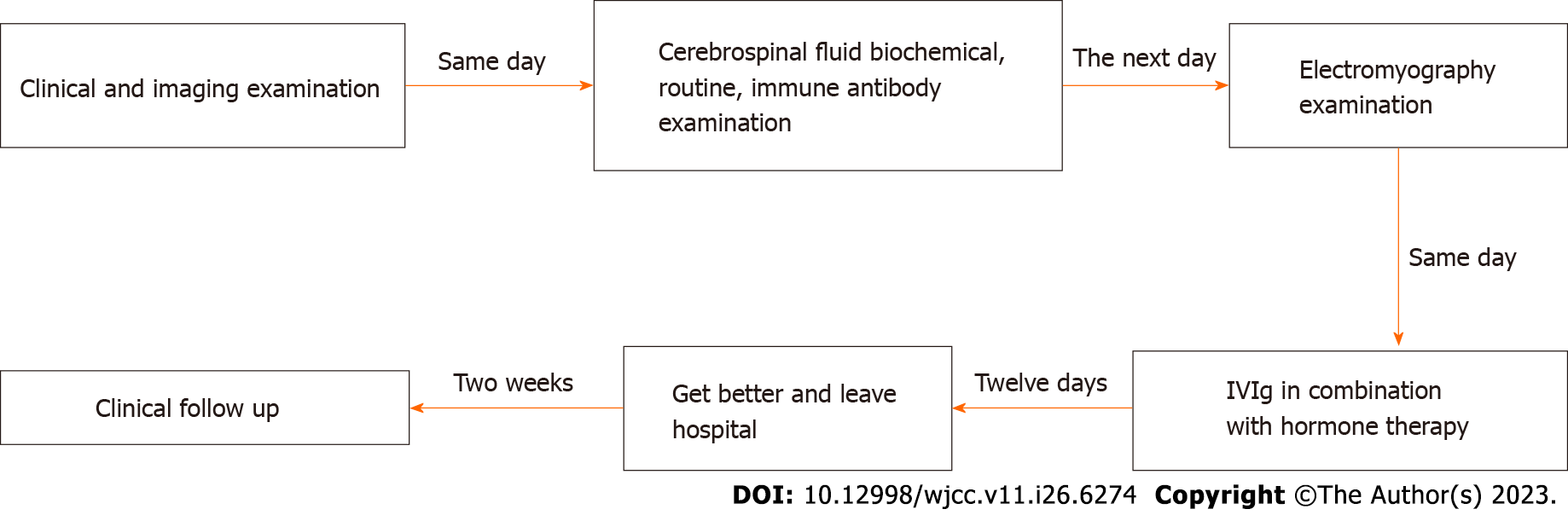

At the time of discharge, she was able to hold objects in each hand securely and could support herself while walking. The pain behind her neck and the numbness of her limbs had resolved significantly, her stool was normal, and she had no urinary incontinence. Two weeks later, the patient was stable (Figure 1).

Anti-sulfatide antibodies have been observed in 5.2% of all GBS cases, mainly in those without a history of prior or occult infection, suggesting that these antibodies may be related to a specific variant or variants of GBS[11]. In this case report, we present a patient with GBS positive for anti-sulfatide antibodies. The CSF showed cytoalbuminologic dissociation. Electromyography suggested multiple peripheral nerve damage. Immunoblotting of the CSF showed positivity for anti-sulfatide antibody. The patient also had symptoms of diaphoresis, positive bilateral pathological signs, normal bilateral deep sensation, and joint position sense. A cervical MRI showed a lamellar and slightly long T2 signal in the medulla at the level of the C2–C3 vertebrae, which we interpreted as evidence of spinal cord involvement (Figure 2).

GBS differs from multiple sclerosis (MS) and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD). MS lesions mainly involve the intracranial region and spinal cord and are characterized by temporal and spatial diversity[12]; GBS patients have no significant abnormalities in cranial MRI. NMOSD is characterized by transverse myelitis and acute optic neuritis, spinal cord lesions that are often larger than three spinal cord segments, and specific antibodies against aquaporin 4[13]; GBS patients usually have a limited extent of spinal cord lesions, and these patients do not have loss of vision or profound or superficial sensory impairment below the plane of a spinal cord injury. Furthermore, evidence of central nervous system demyelinating diseases and CSF-related antibody tests were negative in our patient, although clinical symptoms indicated spinal cord involvement. Our final diagnosis was anti-sulfatide antibody-positive GBS with spinal cord involvement, a novel variant of GBS.

Patients with anti-sulfatide antibody-positive GBS have more significant sensory impairment and less motor impairment than patients with classical GBS. Our patient's symmetrical limb weakness and distal limb sensory disturbances were similar to those of patients with classical GBS. In contrast to Miller-Fisher syndrome, GBS is not characterized by extraocular muscle palsy, although GBS patients often have bilateral hypotonic reflexes and bilateral heel-knee-tibial instability.

Patients with acute panautonomic neuropathy have symptoms of bladder dysfunction and constipation but no symptoms of symmetrical limb weakness. Our patient presented with urinary and fecal retention, bilateral positivity for Babinski’s sign, and MRI findings of intramedullary inflammatory changes at the C2–C3 vertebral body level. Spinal cord involvement is an atypical manifestation of GBS. Patients with atypical variants of anti-sulfatide antibody-positive GBS presenting with multiple cranial nerve involvement, acute bulbar palsy, and myocardial injury leading to transient cardiac insufficiency have previously been reported in China and other countries[10,14]. Spinal cord involvement is the feature unique to our case.

Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) and plasma replacement are effective therapeutic approaches for treating GBS[1]. IVIg inhibits the toxic effects of CD8+ T lymphocytes on the nerve myelin sheath in acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy, decreases the number of B lymphocytes, increases the number of T lymphocytes, and reduces inflammatory cell infiltration. IVIg, therefore, plays a vital role in treatment, especially by restoring the CD4+ T lymphocyte subpopulation[15]. Intravenous methylprednisolone or oral steroids alone are ineffective for treating GBS[16], although IVIg combined with methylprednisolone therapy can provide short-term benefits[17]. Our patient was discharged from the hospital after receiving IVIg with methylprednisolone pulse therapy.

Our report of this unique patient and a thorough literature review highlight the importance of conducting electromyography, analyzing spinal antibodies, and carefully assessing clinical symptoms when encountering atypical presentations of GBS involving spinal cord manifestations to minimize the risk of misdiagnosis. This case report provides a reference for the clinical diagnosis of GBS and its variants. Further studies involving more patients with this GBS variant will contribute to a better understanding of the clinical characteristics of anti-sulfatide antibody-positive GBS and offer valuable insights for diagnosing and treating this syndrome.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Clinical neurology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Tan JK, Malaysia; Viswanathan VK, United States S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | van den Berg B, Walgaard C, Drenthen J, Fokke C, Jacobs BC, van Doorn PA. Guillain-Barré syndrome: pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10:469-482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 525] [Cited by in RCA: 723] [Article Influence: 60.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Filosto M, Cotti Piccinelli S, Gazzina S, Foresti C, Frigeni B, Servalli MC, Sessa M, Cosentino G, Marchioni E, Ravaglia S, Briani C, Castellani F, Zara G, Bianchi F, Del Carro U, Fazio R, Filippi M, Magni E, Natalini G, Palmerini F, Perotti AM, Bellomo A, Osio M, Nascimbene C, Carpo M, Rasera A, Squintani G, Doneddu PE, Bertasi V, Cotelli MS, Bertolasi L, Fabrizi GM, Ferrari S, Ranieri F, Caprioli F, Grappa E, Manganotti P, Bellavita G, Furlanis G, De Maria G, Leggio U, Poli L, Rasulo F, Latronico N, Nobile-Orazio E, Beghi E, Padovani A, Uncini A. Guillain-Barré syndrome and COVID-19: A 1-year observational multicenter study. Eur J Neurol. 2022;29:3358-3367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ariga T, Yu RK. Antiglycolipid antibodies in Guillain-Barré syndrome and related diseases: review of clinical features and antibody specificities. J Neurosci Res. 2005;80:1-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Svennerholm L, Fredman P. Antibody detection in Guillain-Barré syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1990;27 Suppl:S36-S40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Xiao S, Finkielstein CV, Capelluto DG. The enigmatic role of sulfatides: new insights into cellular functions and mechanisms of protein recognition. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;991:27-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Pestronk A, Li F, Griffin J, Feldman EL, Cornblath D, Trotter J, Zhu S, Yee WC, Phillips D, Peeples DM. Polyneuropathy syndromes associated with serum antibodies to sulfatide and myelin-associated glycoprotein. Neurology. 1991;41:357-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wanschitz J, Maier H, Lassmann H, Budka H, Berger T. Distinct time pattern of complement activation and cytotoxic T cell response in Guillain-Barré syndrome. Brain. 2003;126:2034-2042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Souayah N, Mian NF, Gu Y, Ilyas AA. Elevated anti-sulfatide antibodies in Guillain-Barré syndrome in T cell depleted at end-stage AIDS. J Neuroimmunol. 2007;188:143-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dabby R, Weimer LH, Hays AP, Olarte M, Latov N. Antisulfatide antibodies in neuropathy: clinical and electrophysiologic correlates. Neurology. 2000;54:1448-1452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lee KP, Abdul Halim S, Sapiai NA. A Severe Pharyngeal-Sensory-Ataxic Variant of Guillain-Barré Syndrome With Transient Cardiac Dysfunction and a Positive Anti-sulfatide IgM. Cureus. 2022;14:e29261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Caudie C, Quittard Pinon A, Taravel D, Sivadon-Tardy V, Orlikowski D, Rozenberg F, Sharshar T, Raphaël JC, Gaillard JL. Preceding infections and anti-ganglioside antibody profiles assessed by a dot immunoassay in 306 French Guillain-Barré syndrome patients. J Neurol. 2011;258:1958-1964. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | McGinley MP, Goldschmidt CH, Rae-Grant AD. Diagnosis and Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis: A Review. JAMA. 2021;325:765-779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 760] [Article Influence: 152.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Carnero Contentti E, Correale J. Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders: from pathophysiology to therapeutic strategies. J Neuroinflammation. 2021;18:208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 43.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wang KL, Mo JZ, Lu T. [A variant of Guillain Barre syndrome with positive anti sulfatide antibody in multiple cranial nerve involvement: a case report]. Zhongguo Shenjingjingshen Jibing Zazhi. 2022;48:159-161. |

| 15. | Hou HQ, Miao J, Feng XD, Han M, Song XJ, Guo L. Changes in lymphocyte subsets in patients with Guillain-Barré syndrome treated with immunoglobulin. BMC Neurol. 2014;14:202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hughes RA, Swan AV, Raphaël JC, Annane D, van Koningsveld R, van Doorn PA. Immunotherapy for Guillain-Barré syndrome: a systematic review. Brain. 2007;130:2245-2257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 291] [Cited by in RCA: 289] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | van Koningsveld R, Schmitz PI, Meché FG, Visser LH, Meulstee J, van Doorn PA; Dutch GBS study group. Effect of methylprednisolone when added to standard treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin for Guillain-Barré syndrome: randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;363:192-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 241] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |