Published online Sep 16, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i26.6240

Peer-review started: May 26, 2023

First decision: August 8, 2023

Revised: August 19, 2023

Accepted: August 23, 2023

Article in press: August 23, 2023

Published online: September 16, 2023

Processing time: 105 Days and 4.7 Hours

Endometriosis is a common benign gynecological disease that causes dysmenorrhea in women of childbearing age. Malignant tumors derived from endometriosis are rarely reported and are found in only 1% of all patients with endometriosis. Here, we report a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) caused by squamous metaplasia of endometriosis that co-occurred in the uterus and ovaries.

A 57-year-old postmenopausal woman had a 6-month history of irregular uterine bleeding. The uterus and adnexa were examined by computed tomography, and there were two solid cystic masses in the pelvis and right adnexa. Histological findings of surgical specimens showed well-differentiated SCC arising from squamous metaplasia of ectopic endometrial glands in the uterus and ovaries. The patient received chemotherapy after surgery and was followed up for 3 mo without metastasis.

The continuity between ectopic endometrial glands and SCC supports that SCC originates from ectopic endometrial glands with metaplasia towards squamous epithelium.

Core Tip: We report a rare case of squamous cell carcinoma arising from squamous metaplasia of endometriosis that co-occurred in the uterus and ovaries. To date, the reported cases were all treated with paclitaxel combined with carboplatin chemotherapy after radical surgery. In most cases, including ours, the patients tolerated chemotherapy well, and demonstrated dramatic responses, such as disappearance of metastases and no relapse.

- Citation: Cai Z, Yang GL, Li Q, Zeng L, Li LX, Song YP, Liu FR. Squamous cell carcinoma associated with endometriosis in the uterus and ovaries: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(26): 6240-6245

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i26/6240.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i26.6240

Approximately 1% of cases of endometriosis can progress to malignant epithelial tumors, but it is not a precancerous lesion. Age, menopausal hormone levels, and obesity index are currently believed to be risk factors for endometriosis progression[1]. Recent studies showed that when patients with endometriosis experience genetic mutations such as ARID1A and PIK3CA, or changes in mismatch repair enzymes and microsatellite instability genes, endometriosis is more prone to malignancy[2,3]. In most cases, we acknowledged that ovarian tumors arise from a cystic teratoma or less frequently from Brenner tumor or endometriosis. The most common ovarian cancers arising from endometriosis are endometrioid and clear cell carcinoma, malignant mixed mullerian tumors, and endometrial stromal sarcoma. When endometriosis undergoes squamous metaplasia and malignant transformation, ovarian squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) develops, which is only occasionally reported[4]. Carboplatin and paclitaxel were used experimentally in those patients. However, the chemotherapeutic effect in some patients was disappointing[5].

A 57-year-old female patient suffered from irregular vaginal bleeding for 5 mo.

No other abnormal clinical signs.

The patient underwent cervical conization in 2000 because of atypical epithelial cells in the cervix. Postoperative cervical human papillomavirus (HPV) screening showed no abnormalities. Elevated carbohydrate antigen (CA) 125 and CA199 levels were found 9 years before.

The patient denied any family history of malignancies.

On physical examination, the patient’s body temperature, pulse, and breathing were normal, and vital signs were stable.

Serum analysis showed elevated levels of CA125 (114.5 U/mL), CA199 (> 700 U/mL), and human epididymis protein 4 (HE4) (121 mol/L).

Computed tomography (CT) examination in our hospital showed a solid cystic mass 5.9 cm × 8.3 cm × 6.7 cm in size in the left pelvis and a solid cystic mass 3.6 cm × 3.7 cm × 3.8 cm in the right adnexa (Figure 1).

Hysteroscopy showed no abnormalities in the cervical canal, but a neoplasm was noted on the left posterior wall of the uterine cavity. Pathological diagnosis of the hysteroscopic biopsy revealed no tumor signs in the cervical canal, and the uterine cavity tissue showed mildly atypical squamous epithelium.

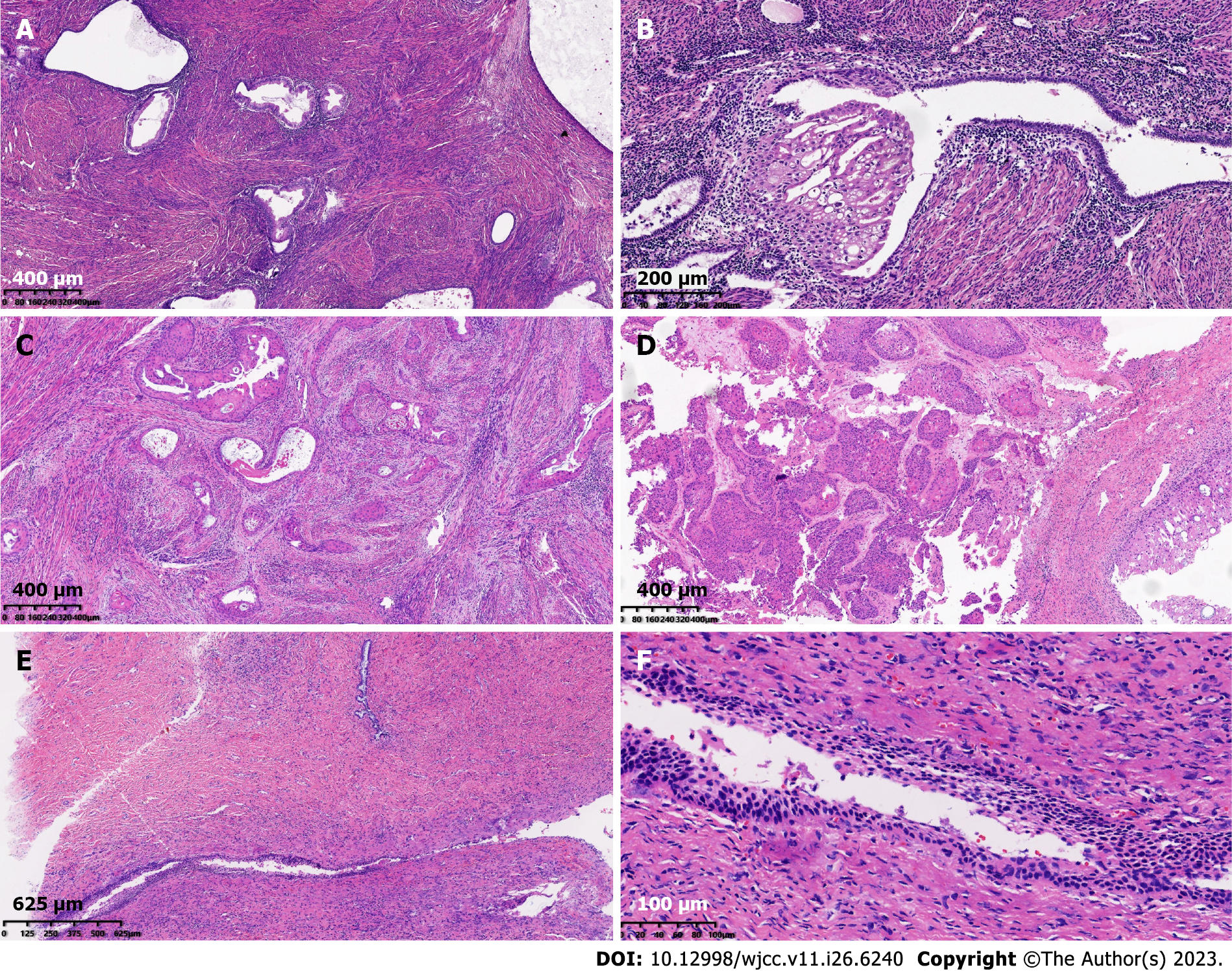

The patient underwent hysterectomy and bilateral ovariectomy, and histological analysis of the surgical specimens demonstrated progression of endometrial gland metaplasia towards squamous cells in the myometrium, fallopian tubes, and ovarian stroma. Some glands were severely atypical and infiltrating, with keratinized beads and necrosis visible. No tumor thrombi were found in the vasculature (Figure 2). There was no abnormal squamous epithelium in the cervix. As for the percentages of endometriosis and SCC in the different cites, about 55% of ectopic glands that occur in the uterine myometrium undergo transformation to squamous metaplasia, and about 45% of squamous glands undergo malignant transformation. The proportion of squamous metaplasia in the left ovary is approximately 50%, and the proportion of SCC is approximately 50%. The ratio of malignant transformation of ectopic glands in the right ovary is approximately 90%. The left fallopian tube only shows ectopic glandular squamous metaplasia, while the right fallopian tube only shows inflammation. Immunohistochemistry was positive for cytokeratin, P63, and P40 expression in cancer cells, while WT-1 and PAX8 were negative, with Ki-67 accounting for approximately 5%. Estrogen receptor completely delineated the ectopic glands (Figure 3). Therefore, the final diagnosis was highly differentiated SCC arising from squamous metaplasia of endometriosis.

The patient was treated with cadonilimab, paclitaxel and carboplatin chemotherapy after radical hysterectomy with bilateral adnexectomy.

The serum levels of CA125 and CA199 postoperatively were significantly lower than before surgery and remained normal. SCC-associated antigen was still at an abnormal level of 3.06 ng/mol. The patient received chemotherapy after surgery and was followed up for 3 mo without metastasis or relapse.

This is the first report of SCC arising from endometriosis with squamous metaplasia that occurred simultaneously in the uterus and ovaries. The initial symptom was irregular vaginal bleeding. Imaging examination showed cystic ovarian masses and unclear uterine imaging, and serum analysis showed elevated levels of CA125 and CA199. However, CA125 levels show no significant difference between endometriosis progression and benign ovarian lesions[6]. The combined measurement of HE4 and CA125 is effective for diagnosis of ovarian cancer and may be beneficial as a screening test[7,8]. However, diagnosis of this disease still depends on postoperative pathological examination. Malignant tumors derived from endometriosis have been increasing, and regular follow-up and reexamination are necessary for these patients.

Under the microscope, the ectopic endometrial glands appeared in the myometrium and ovarian stroma; some of which showed metaplasia towards the squamous epithelium. The columnar epithelium of some ectopic glands was continuous with tumor cells. Tumor cells had differentiation characteristics in squamous epithelium, and were arrayed as nests and infiltrated with a large amount of keratinization. The continuity between columnar epithelium and tumor components indicated that the tumor originated from squamous metaplasia of ectopic endometrial glands. Given the high differentiation of the tumor and the presence of squamous metaplasia glands and SCC in both the ovaries and uterus, we considered that worsening of endometriosis coincided in the uterus and ovaries rather than a single primary metastasis in our patient.

Differential diagnosis in this patient was as follows: (1) Endometrioid adenocarcinoma with squamous epithelial differentiation: 20%-50% of endometrioid adenocarcinomas undergo squamous epithelial differentiation, and are classified as a particular subtype; (2) Cervical SCC: This carcinoma can spread to the uterine cavity, and the pure SCC nests infiltrate the myometrium, which is rare. It is necessary to prove continuity of the lesion; (3) Primary endometrial SCC: The diagnostic criteria for primary endometrial SCC are that it does not coexist with endometrial adenocarcinoma or cervical SCC; and (4) Primary ovarian SCC derived from a mature cystic teratoma: 80% of primary ovarian SCCs are derived from a dermoid cyst/mature cystic teratoma, occasionally seen in endometriosis and Brenner’s tumor. Our patient had undergone cervical conization in 2000, and no abnormalities were found following HPV examinations in November 2022. There was no abnormal squamous epithelium in the cervix under the microscope; thus, the possibility of cervical origin was ruled out. The glandular structure of the myometrium and ovarian stromal heterotopic tissue was normal; the columnar epithelium of some ectopic glands was continuous with tumor cells. Based on the patient’s clinical data and pathological findings, she simultaneously developed endometriosis of glandular tissue in the deep myometrium and ovarian stroma, with ectopic squamous epithelium and malignant transformation into SCC.

Such patients are rare in clinical practice, and standardized treatment has not been developed. The reported cases of ovarian SCC arising from endometriosis were all treated with paclitaxel combined with carboplatin chemotherapy after radical surgery. Some patients tolerated chemotherapy well, and demonstrated a dramatic response[9,10]. Our patient received chemotherapy after surgery and was followed up for 3 mo without metastasis (Table 1)[11-13]. However, there are also cases of poor prognosis after chemotherapy; therefore, more advanced treatment plans are needed for patients with disappointing chemotherapy outcomes.

| ID | Ref. | Age (yr) | Diagnosis | Treatment | Follow-up outcome |

| 1 | [5] | 43 | Squamous cell carcinoma of the ovary | Paclitaxel and cisplatin | Vaginal metastases |

| 2 | [11] | 52 | Squamous cell carcinoma of the ovary | Paclitaxel and cisplatin | Without metastases |

| 3 | [12] | 47 | Squamous cell carcinoma of the ovary | Paclitaxel and cisplatin | Liver metastases |

| 4 | [13] | 45 | Squamous cell carcinoma of the ovary | Paclitaxel and cisplatin | Pelvic metastases |

| 5 | [10] | 31 | Squamous cell carcinoma of the ovary | Paclitaxel and cisplatin | Without recurrence |

| 6 | [9] | 46 | Squamous cell carcinoma of the ovary with lung metastasis | Paclitaxel and cisplatin | Tumor progression and aggravation |

| 7 | Our case | 57 | Squamous cell carcinoma of the ovary and uterus | Paclitaxel and cisplatin | Without metastases |

Primary ovarian SCC requires the exclusion of cervical SCC and uterine SCC metastasis, but metastatic lesions often involve simultaneous metastasis of both ovaries. The continuity between ectopic endometrial glands and SCC supports that SCC originated from ectopic endometrial glands. Both the reported cases and our case were treated with paclitaxel combined with platinum-based chemotherapy, with significant differences in efficacy among different patients. Therefore, more cutting-edge treatment plans are urgently needed for patients with poor chemotherapeutic efficacy.

| 1. | Wei JJ, William J, Bulun S. Endometriosis and ovarian cancer: a review of clinical, pathologic, and molecular aspects. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2011;30:553-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Anglesio MS, Yong PJ. Endometriosis-associated Ovarian Cancers. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2017;60:711-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Suda K, Cruz Diaz LA, Yoshihara K, Nakaoka H, Yachida N, Motoyama T, Inoue I, Enomoto T. Clonal lineage from normal endometrium to ovarian clear cell carcinoma through ovarian endometriosis. Cancer Sci. 2020;111:3000-3009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Guidozzi F. Endometriosis-associated cancer. Climacteric. 2021;24:587-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Xu Y, Li L. Primary squamous cell carcinoma arising from endometriosis of the ovary: A case report and literature review. Curr Probl Cancer. 2018;42:329-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | de Souza MLP, da Costa TP, de Freitas NP, de Souza MF, Athanazio DA. The many faces of endometriosis. Autops Case Rep. 2022;12:e2021409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Dochez V, Caillon H, Vaucel E, Dimet J, Winer N, Ducarme G. Biomarkers and algorithms for diagnosis of ovarian cancer: CA125, HE4, RMI and ROMA, a review. J Ovarian Res. 2019;12:28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 350] [Article Influence: 50.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Dai HY, Hu F, Ding Y. Diagnostic value of serum human epididymis protein 4 and cancer antigen 125 in the patients with ovarian carcinoma: A protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:e25981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yamakawa Y, Ushijima M, Kato K. Primary squamous cell carcinoma associated with ovarian endometriosis: a case report and literature review. Int J Clin Oncol. 2011;16:709-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Eltabbakh GH, Hempling RE, Recio FO, O'Neill CP. Remarkable response of primary squamous cell carcinoma of the ovary to paclitaxel and cisplatin. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:844-846. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cucinella G, Sozzi G, Di Donna MC, Unti E, Mariani A, Chiantera V. Retroperitoneal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Involving the Pelvic Side Wall Arising from Endometriosis: A Case Report. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2022;87:159-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hasegawa E, Nishi H, Terauchi F, Isaka K. A case of squamous cell carcinoma arising from endometriosis of the ovary. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2011;32:554-556. |

| 13. | Park JW, Bae JW. Pure primary ovarian squamous cell carcinoma: A case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2015;9:321-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Pathology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Handra-Luca A, France S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Chen YL