Published online Sep 16, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i26.6031

Peer-review started: May 13, 2023

First decision: July 4, 2023

Revised: July 21, 2023

Accepted: August 9, 2023

Article in press: August 9, 2023

Published online: September 16, 2023

Processing time: 117 Days and 22.2 Hours

Fasting during the month of Ramadan is one of the five fundamental principles of Islam, and it is obligatory for healthy Muslim adults and adolescents. During the fasting month, Muslims usually have two meals a day, suhur (before dawn) and iftar (after dusk). However, diabetic patients may face difficulties when fasting, so it is important for medical staff to educate them on safe fasting practices. Prolonged strict fasting can increase the risk of hypoglycemia and diabetic ketoacidosis, but with proper knowledge, careful planning, and medication adjustment, diabetic Muslim patients can fast during Ramadan. For this review, a literature search was conducted using PubMed and Google Scholar until May 2023. Articles other than the English language were excluded. Current strategies for managing blood sugar levels during Ramadan include a combination of patient education on nutrition, regular monitoring of blood glucose, medications, and insulin therapy. Insulin therapy can be continued during fasting if properly titrated to the patients’ needs, and finger prick blood sugar levels should be assessed regularly. If certain symptoms such as hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, dehydration, or acute illness occur, or blood glucose levels become too high (> 300 mg/dL) or too low (< 70 mg/dL), the fast should be broken. New insulin formu

Core Tip: During Ramadan, most Muslims have two meals a day: Suhur (before dawn) and iftar (after dusk). Medical staff should educate Muslim patients on safe fasting to ease difficulties for diabetic patients. Controlling blood sugar levels involves a multi-pronged approach with patient education, monitoring, medications, and insulin. Insulin therapy can be continued during fasting if adjusted to the patients’ needs. New medications like pegylated insulin, dual agonists, and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors offer additional cardiovascular benefits for diabetic patients.

- Citation: Ochani RK, Shaikh A, Batra S, Pikale G, Surani S. Diabetes among Muslims during Ramadan: A narrative review. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(26): 6031-6039

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i26/6031.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i26.6031

One of Islam’s five pillars and an obligation for all healthy Muslim adults and adolescents is fasting throughout the month of Ramadan. The majority of Muslims only eat two meals a day, suhur (before dawn) and iftar (after dusk) when fasting. Even though, they are free from this requirement, pregnant women and sick people frequently fast[1]. Recent global data suggests that over 148 million muslims are diabetics, and despite the exemption to fast, 116 million of them choose to fast. Furthermore, with lack of food intake for a longer period of time, the most commonly reported symptom is hypoglycemia. A study done on a semi-structured focus group of 53 participants with type 2 diabetes mellitus, who fasted during Ramadan, showed that 43% of them reported having hypoglycemia, and 13% of the total participants reported having a fear of developing hypoglycemia while fasting[2]. This demonstrates that, despite the fact that people with diabetes mellitus and the elderly are excluded from fasting, the urge to fast still outweighs health considerations[3].

As a general rule, during a fast, one is not permitted to consume any food or drink, including through gastrostomy tubes, or take any medications through any mucosal route, including the mouth, nose, or rectum[3]. A person’s glycemic control, weight, and lipid profile may alter as a result of changes in diet, physical activity, and sleep patterns, which may necessitate adjusting insulin doses and timing as well as oral hypoglycemic medications[4]. It is crucial that medical staff educate Muslim patients about safe fasting to minimize the difficulties that diabetic persons can have when fasting[2]. Therefore, to expand upon the subject of diabetic patients fasting during the month of Ramadan, we write this review regarding the implications in diabetic patients when fasting during Ramadan, its pathophysiology, treatment regimen, and the complications associated with this.

For this review, a literature search was conducted using PubMed and Google Scholar until May 2023. The search string included the following keywords: ("Diabetes mellitus and importance of Ramadan") or ("pathophysiology" and "complication" and "management" and "risk-factors"). Articles other than English language were excluded.

Ramadan is the ninth month of the Islamic calendar and is widely regarded as the most important month by Muslims with significant historical and religious implications. Some reasons for its significance include it being the month Muslims believe the Holy Quran was revealed to the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him), and Muslims were commanded to observe fast, abstaining from all sustenance, from sunrise till sunset[5].

While there is widespread awareness regarding the practice of fasting by Muslims during Ramadan, it is not the only purpose. Muslims from around the globe also believe that this is the month where prayer, recitation of the Quran, and community-serving charitable contributions should be given the utmost importance[6]. Muslims refrain from daily norm social practices as well as participation in entertainment-seeking behavior. In Muslim-majority countries, work hours are also altered and reduced[7].

The actual practice of fasting is only one of the fundamental pillars of Ramadan. In its totality, the month is supposed to harmoniously bring together a community of Muslims together in practice where they can learn how to abstain from daily comforts and pleasures in order to better appreciate their lives, experience a glimpse of the hardships of less fortunate people around the world and to practice their faith repetitively so that certain practices can carry over to the rest of the year[8].

The pathophysiology of the disease has been well-explained in previous literatures. However, the relationship between diabetes in fasting in healthy individuals and diabetics will be expanded upon further.

Beta-cells of the pancreas are responsible for the production of insulin, which is synthesized from pre-insulin. While maturing, pre-insulin goes through several conformational processes in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to change to pro-insulin. Proinsulin is then transported from the ER to the Golgi apparatus, where it enters immature secretory vesicles and is broken into C-peptide and insulin. After the maturation process, the insulin is stored in granules and is released under the trigger of high glucose levels. Some other components can also trigger the release of insulin, including amino acids, fatty acids, and hormones[9-11].

During the first few hours of fasting, glucose levels fall, inhibiting insulin secretion. When glucose levels fall below the physiologically normal range of 65-70 mg/dL, two counterregulatory hormones, epinephrine, and glucagon, are activated and released. This causes glucagon to initiate hepatic glycogenolysis and epinephrine to seek to keep glucose levels within the normal physiological range[3,9]. As fasting progresses, the levels of these two hormones keep increasing, eventually causing the formation of glucose via a combination of two mechanisms, i.e., previously activated glycogenolysis and newly-activated gluconeogenesis, which forms de novo glucose with the help of amino-acids residues and glycerol. After the depletion of hepatic glycogen levels, which can take anywhere from 12 to 36 h, ketone bodies are produced by mobilizing fatty acids from adipose tissue. These ketone bodies are used as a source of fuel for vital organ functions, while glucose is saved for the brain and erythrocytes[3,9,12-14].

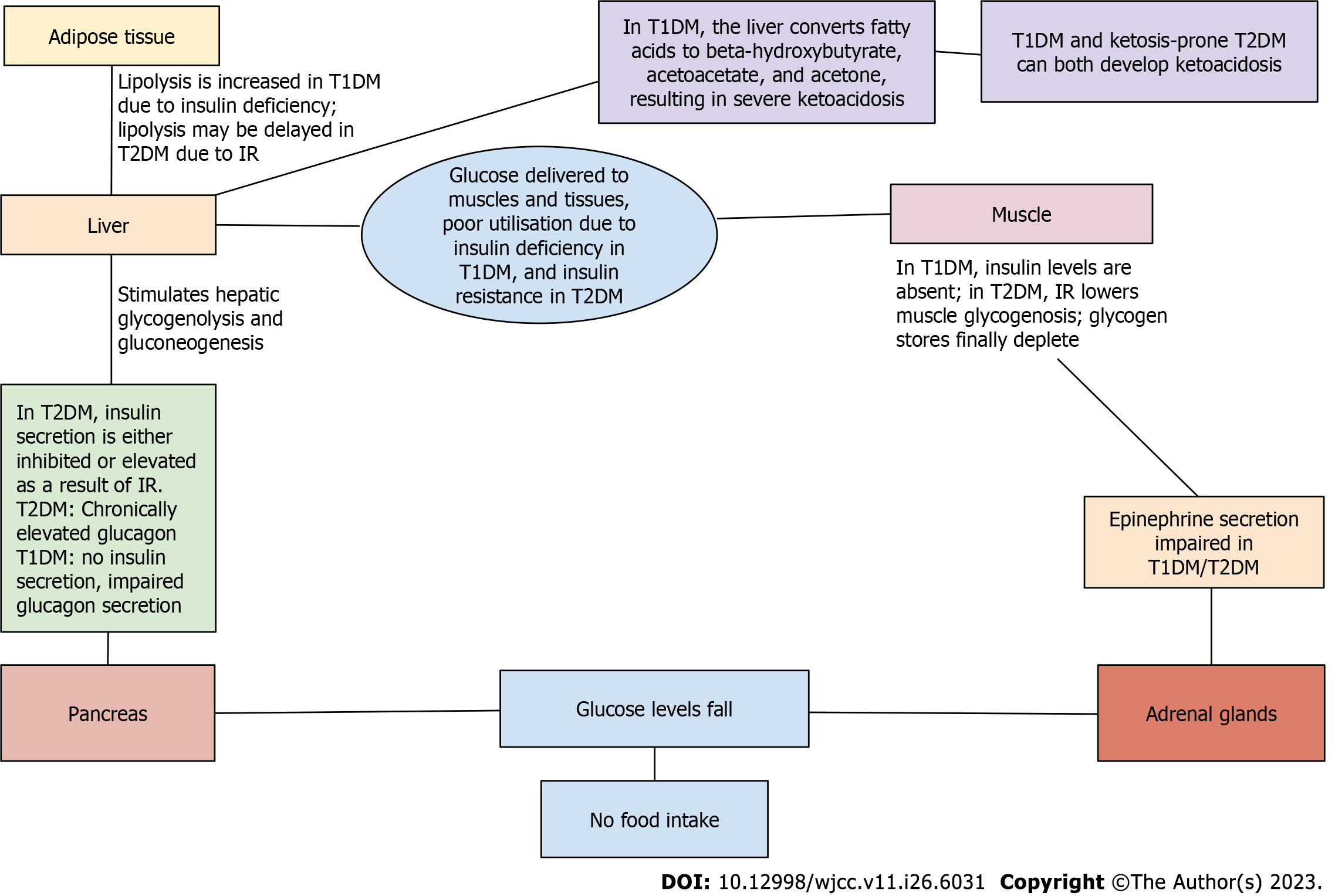

These free fatty acids undergo beta-oxidation in the liver, producing ketones such as beta-hydroxybutyrate (-OHB) and acetoacetate, which are used to generate energy by the brain, muscles, and other tissues. The usage of ketones aids in the preservation of lean muscle mass, the improvement of body composition, the optimization of physiological function, and the slowing of aging and disease processes (Figure 1)[3,12,13,15,16].

The physiology of fasting in diabetics varies with the type of diabetes. For those with type-2 diabetes, insulin resistance is the primary process. However, with increasing severity, the beta-cells can get exhausted and have a similar picture to type-1 diabetes mellitus. During the early stages of type 2 diabetes, adopting a fasting or extremely low-calorie diet, or practicing controlled fasting with slight weight loss, can lead to positive outcomes for the underlying pathophysiological factors of insulin resistance and adiposity, ultimately resulting in the normalization of blood sugar levels. In essence, this can reverse the T2 diabetes phenotype[3,9,12].

Nonetheless, in the absence of exogenous insulin, there is a theoretical possibility of significant hyperglycemia and clinically relevant ketogenesis in individuals with advanced type 2 diabetes, particularly those with type 1 diabetes, where insulin deficiency is absolute. Furthermore, the risk of severe hypoglycemia may emerge as a result of defective hypoglycemic counterregulatory responses, an inability to diminish circulating insulin of exogenous origin, and decreased adrenal and sympathetic neural tone. When patients have poor diabetes control, as seen by persistent hyperglycemia, the threshold for the release of counterregulatory hormones rises, in contrast to patients who have recurrent hypoglycemia, such as those who maintain stringent diabetic control. This process has been demonstrated in Figure 2[3,12,17,18].

A study done by Lessan and colleagues on 56 diabetic patients (50 type 2 diabetics and six types 1 diabetics) showed that in periods of Ramadan and non-Ramadan, there was a statistically significant difference in mean glucose levels during the period of 24 h[19].

Since Islam constitutes one of the major global religions, it is probable that a healthcare provider will come across an Islamic patient during their practice. It is important for a physician to develop cultural sensitivity towards such patients, especially during the holy month of Ramadan[20]. It is a concern that strict fasting for prolonged periods could put the patient at risk for episodes of hypoglycemia and diabetic ketoacidosis. However, with adequate knowledge, a cautious approach, and medication adjustment as described below, Islamic patients with diabetes should be able to fast during Ramadan.

The current regimens used to control blood sugar levels in patients during Ramadan involve a multicentric approach[21]. Intermittent fasting, which is only gaining popularity in recent times, includes abstinence from the consumption of any calories for more than twelve hours, followed by food consumption for a brief period of time in repeated cycles[22]. Ramadan is a type of intermittent fasting where people fast during the day and break their fast at night. Two major meals are consumed during this time: The iftar, when the fast is broken before sunset after a long day of fast, and the suhur, when a calorie-dense meal is consumed before sunrise just before starting the day-long fast[21]. Intermittent fasting is found to improve insulin resistance by reducing the intake of calories, which has been shown to halt the progression of chronic diseases such as diabetes by downstream endocrine signaling[22]. Although, it is recommended that patients with diabetes who wish to undergo fasting for Ramadan should plan at least two-three months prior so that their body gets enough time to get acclimatized to the new dietary schedule[23]. It is generally recommended that patients with diabetes stop their oral sulfonylurea medications during Ramadan or use them with extreme caution due to the risk of hypoglycemia[1,24].

Insulin therapy can be continued during fasting if titrated well according to the patients’ requirements. Patients’ baseline glycaemic control must be taken into consideration with regular assessment of finger prick blood sugar levels[23]. Basal insulin such as neutral protamine hagedorn and glargine are taken once or twice a day and provide coverage over long hours. Bolus insulin can be short-or rapid-acting, providing mealtime coverage[25]. If a patient is on once-a-day basal insulin, they should take it with the Iftar meal with a slight reduction in the dose based on the patients’ baseline sugar levels. If a patient is on twice-a-day basal insulin, they must take the usual dose along with their iftar meal but reduce the second dose taken with the suhur mean depending on the glycaemic control[21]. For patients on rapid-acting insulin, it is important to continue the same dose with their Iftar meal and take the second mealtime dose with their Suhur meal, titrating the dosage to a lower level[26]. Pre-mixed insulin regimens correspond more closely to the physiologic secretion of insulin in our body, such as insulin lispro 75/25 (75% insulin lispro protamine suspension and 25% insulin lispro) and biphasic insulin aspart 70/30 (70/30; 70% insulin aspart protamine suspension and 30% insulin aspart). These suspensions suit patients who need both basal and mealtime insulin dosages[27]. It is recommended during Ramadan that the patient take their usual morning dose with their Iftar meal and reduce the dosage of evening insulin along with their suhur meal. It is always important to keep a constant check on the patients’ blood sugar levels to prevent hypoglycemia. Patients should also ensure adequate hydration and should be educated about breaking the fast if they feel unwell[28].

Many Muslim patients may avoid going to the doctor before Ramadan out of concern that they might be told not to fast. Therefore, this prompts them to change their course of treatment without consulting a doctor[3]. Hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, diabetic ketoacidosis, dehydration, and thrombosis are complications brought on by such changes[29].

Patients with type 1 diabetes had a 4.7-fold increased risk of hypoglycemia, compared to a 7.5-fold rise in type 2 diabetes patients. This number is frequently under-reported, though, because mild to moderate hyperglycemia typically does not necessitate medical attention. Numerous hours of fasting and failure to alter medicine dosages may be contributing factors[29]. According to the epidemiology of diabetes and Ramadan 1422/2001 study, patients with type 2 diabetes saw a five-fold increase in the chance of developing severe hyperglycemia during Ramadan, while those with type 1 diabetes experienced a three-fold increase in the risk of experiencing severe hyperglycemia with or without ketoacidosis. However, if a person has high blood sugar levels before Ramadan, their chance of developing diabetic ketoacidosis increases during fasting[21].

Additionally, a report from Saudi Arabia indicated that individuals who fasted throughout Ramadan had a higher risk of retinal vascular occlusion. Dehydration results from the persons’ inability to drink fluids while fasting. In hot, humid areas and in those who engage in strenuous physical activity on a daily basis, the severity worsens. The patient becomes hypercoagulable as a result of the intravascular space contracting due to an increase in clotting factors, a decrease in endogenous anticoagulants, and impaired fibrinolysis. One of the factors that raise the risk of thrombosis is an increase in blood viscosity[21].

Fasting during Ramadan is associated with increased variability in glucose levels and has been associated with an increased risk for both hyperglycemia as well as hypoglycemia in diabetic patients[1,30]. A previous incidence of hypoglycemia during non-fasting months also significantly increases the risk of encountering another hypoglycemic episode during fasting, as the Multi-country retrospective observational study of the management and outcomes of patients with diabetes during Ramadan study demonstrated[31]. Other studies conducted across multiple geographies have demonstrated similar findings[32,33]. One study also showed a > 4-fold increase in severe hypoglycemic episodes requiring hospitalization in diabetic patients during Ramadan[34].

The use of sulfonylureas and insulin is associated with a greater risk of hypoglycemic episodes[33] as compared to glucagon-like-peptide-1 receptor agonists and 2nd generation sulfonylureas[35,36]. Hypoglycemia risk can also be elevated in regions with longer fasting durations, hot and arid atmospheres, and culturally distinct dietary practices[37].

The management of hypoglycemia during Ramadan focuses on two aspects of treatment. Firstly, pre-Ramadan preparation and treatment of diabetes to ensure strong long-term glucose control, and secondly, signs and symptoms awareness in patients in order to recognize when to break the fast, if necessary, as well as maintaining regular monitoring of blood glucose.

Nutritional patient education: Three months before Ramadan and the intended date of fasting initiation, pre-treatment education, and counseling should be initiated with the help of a multidisciplinary team. Dosages of all drugs should be stabilized, and a two-time regimen should be devised (pre and post-fast). If receiving insulin, self-titration should be practiced and taught. Additional considerations for co-morbid diseases such as chronic kidney disease should also be noted, and dietary and drug practices should be modified accordingly[37].

Prespecified, individualized macronutrient and energy requirement prescriptions: Prespecified, individualized macronutrient and energy requirement prescriptions in attunement with the medications being administered should be devised and recommended to the patients. Duration and total daily energy expenditure should be considered. Adequate, measured macronutrient intake (carbohydrate ≤ 130 grams/d) has been known to reduce the rate of hypoglycemic episodes. Other recommendations include daily dietary cholesterol < 300 milligrams/d and the division of meals into four unequally distributed meals with the highest carbohydrate load pre- and post-iftar immediately[38].

Regular blood glucose monitoring: Patients need to be encouraged to self-monitor glucose up to two times a day if at moderate risk of hypoglycemic episodes. However, if elevated risk is observed, a 7-point time scale monitoring method is recommended daily[39].

Medications: It is recommended to switch to glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists from sulfonylureas, adjust doses, and consider the value of sodium–glucose-cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors. Insulin delivered twice daily based on self-titrated and self-blood glucose monitoring is recommended[30].

Recognizing signs of severity: Certain signs of self-monitoring or the presence of certain symptoms have been associated with worsening hypoglycemic episodes associated with severe morbidity. For these indications, it is recommended that the fast should be immediately broken. These factors have been listed as the following[1]: (1) Blood glucose > 300 mg/dL; (2) blood glucose < 70 mg/dL; and (3) symptoms of hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, dehydration, or acute illness.

What's new in the treatment of diabetes: Recently, there have been some new insulin formulations that have been approved for the treatment of diabetes. Pegylated insulin moieties containing polyethylene glycol attached to the basic insulin structure have become more common because they ensure a slow and steady absorption of insulin from the injected site. Externally providing heat to the subcutaneously injected site has also been shown to increase the absorption of insulin[40].

Apart from modifications in insulin structures and function, there has been an increasing rise in incretin-based treatments for patients with diabetes[41]. Incretins are hormones that stimulate insulin secretion after the consumption of a meal in correspondence with the rising glucose levels. The glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and GLP-1 are the two most common incretins[42]. A new concept of “twincretin” is also coming up, such as the drug tirzepatide which is a dual agonist of both GIP and GLP-1 receptors, thus increasing the efficacy of insulin release[43]. Semaglutide, a GLP-1 agonist, is gaining popularity not only for its treatment in diabetes mellitus but also because it has been shown to cause weight loss in obese patients, which is also a risk factor for developing insulin resistance and diabetes[44].

There has also been a rise in the usage of non-insulin-dependent medications such as SGLT2 inhibitors. These drugs prevent the renal reabsorption of glucose, thus enhancing its excretion and lowering blood sugar levels. The most recent SGLT inhibitor approved by the Food and Drug Administration is ertugliflozin, which has been found to have additional cardiovascular benefits in patients with type 2 diabetes (2017)[45,46].

Apart from its beneficial effects of increasing insulin release, as described above, GIP also causes fat deposition in the adipocytes, thus contributing to insulin resistance[41]. There are upcoming studies being done to see if GIP antagonists might have beneficial effects in reversing this insulin resistance and possibly metabolic syndrome. There are certain drugs with unknown mechanisms, such as dopamine receptor agonist bromocriptine that seem to be beneficial in the treatment of diabetes. It is found to reduce patients’ fasting and postprandial blood glucose levels without having any effect on the release of insulin in the body[47]. With the wide array of medications available for patients with diabetes, it is important for a physician to keep themselves updated with the most recent and upcoming treatment modalities.

Pre-Ramadan medical evaluation: Before embarking on fasting during Ramadan, it is essential for diabetic individuals to undergo an assessment one to two months prior to the commencement of the holy month. This evaluation serves the purpose of gauging the patients’ diabetes management, as well as identifying any acute and chronic diabetes-related complications and other coexisting medical conditions. The assessment is crucial in determining the level of risk the patient might face during Ramadan fasting, which is classified as very high, high, or moderate/low according to the International Diabetes Federation’s criteria. Based on this risk categorization, patients should be appropriately advised regarding the feasibility of observing the fast. Raising the patients’ understanding of the potential risks associated with fasting during Ramadan can significantly decrease the likelihood of complications. Proper education regarding dietary habits, physical activity, dosage of medications and recognition of warning signs is crucial[48,49].

It is imperative to encourage all diabetic patients to have the pre-dawn meal on fasting days. Ideally, a diet inclusive of slow energy-releasing complex carbohydrates for the predawn meal and simple carbohydrates for sunset meal. While diabetic patients can engage in their regular physical activities, including moderate exercise, they should be cautious about excessive physical exertion, especially in the evening, to prevent hypoglycemia. Some patients may choose not to monitor their blood glucose during fasting, fearing that finger pricking for blood sugar testing breaks the fast. Therefore, it is important to clarify to patients that this belief is a misconception and monitoring blood glucose levels is essential for their well-being[49-51].

Adjusting diabetes medications: Various diabetic medications have been described in the literature and clinical practice. Medications such as metformin, dipeptidyl peptidase 4 -inhibitors (sitagliptin), thiazolidinediones, short-acting insulin secretagogues can be used during fasting in diabetic individuals. However, medications like sulfonyl carry a higher risk of hypoglycemia, and SGLT2 inhibitors with their increased risk of dehydration as well as the urinary tract infections should typically be avoided in fasting diabetic individuals[52].

Insulins: Ramadan fasting poses an increased risk of hypoglycemia for individuals undergoing insulin treatment. To mitigate this risk while fasting, those using premixed insulin can consider switching to a multiple-dose regimen comprising a basal insulin and short-acting insulin administered before meals. The short-acting insulin dose should be adjusted according to the expected carbohydrate intake for each meal. However, this risk can also be mitigated with the use of an insulin pump during Ramadan[30,36].

Monitoring of blood glucose while fasting: Frequent monitoring of blood glucose during fasting is critical and as mentioned earlier, pricking your finger while fasting does not break the fast[51].

Additionally, incase of any hypoglycemic symptoms, the fast can be broken and it is acceptable under the laws of Islam. Management of complications in diabetic patients remains the same during Ramadan as it does usual.

Muslims consider Ramadan, the ninth month of the Islamic calendar, to be the most significant month historically and religiously. During this month, the majority of Muslims only eat two meals a day, suhur (before dawn) and iftar (after dusk), after fasting for around 30 d. It is important for medical staff to educate Muslim patients on safe fasting practices, particularly for those with diabetes who may face difficulties. Current strategies for managing blood sugar levels during Ramadan involve a multidisciplinary approach, including nutritional education, regular blood glucose monitoring, medications, and insulin therapy. Insulin therapy can be continued during fasting if properly adjusted to the patients’ needs. Patients on once-a-day basal insulin should take it with the Iftar meal, with a slight reduction in the dose based on their baseline sugar levels. Patients on twice-a-day basal insulin should take the usual dose with their iftar meal but reduce the second dose taken with the suhur meal based on their glycaemic control. Newer insulin formulations, such as pegylated insulin moieties, and drugs like tirzepatide, a dual agonist of both GLP-1 and GIP, have been introduced. Additionally, newer medications like SGLT2 inhibitors, including ertugliflozin, have shown many benefits, including additional cardiovascular benefits for patients with type 2 diabetes. Encourage diabetic patients to have a pre-dawn meal on fasting days with slow energy-releasing complex carbohydrates. For the sunset meal, opt for simple carbohydrates. Moderate exercise is allowed, but caution is advised against excessive physical exertion in the evening to prevent hypoglycemia. Clarify that monitoring blood glucose during fasting is essential for their well-being, as finger pricking does not break the fast.

| 1. | Shaikh S, Latheef A, Razi SM, Khan SA, Sahay R, Kalra S. Diabetes Management During Ramadan. 2022 May 18. In: Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000–. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Hassanein MM, Hanif W, Malek R, Jabbar A. Changes in fasting patterns during Ramadan, and associated clinical outcomes in adults with type 2 diabetes: A narrative review of epidemiological studies over the last 20 years. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2021;172:108584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Ahmed SH, Chowdhury TA, Hussain S, Syed A, Karamat A, Helmy A, Waqar S, Ali S, Dabhad A, Seal ST, Hodgkinson A, Azmi S, Ghouri N. Ramadan and Diabetes: A Narrative Review and Practice Update. Diabetes Ther. 2020;1-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hui E, Devendra D. Diabetes and fasting during Ramadan. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2010;26:606-610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Toda M, Morimoto K. [Effects of Ramadan fasting on the health of Muslims]. Nihon Eiseigaku Zasshi. 2000;54:592-596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sakr AH. Fasting in Islam. J Am Diet Assoc. 1975;67:17-21. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Roky R, Houti I, Moussamih S, Qotbi S, Aadil N. Physiological and chronobiological changes during Ramadan intermittent fasting. Ann Nutr Metab. 2004;48:296-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Abolaban H, Al-Moujahed A. Muslim patients in Ramadan: A review for primary care physicians. Avicenna J Med. 2017;7:81-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Galicia-Garcia U, Benito-Vicente A, Jebari S, Larrea-Sebal A, Siddiqi H, Uribe KB, Ostolaza H, Martín C. Pathophysiology of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 1676] [Article Influence: 279.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Dimas AS, Lagou V, Barker A, Knowles JW, Mägi R, Hivert MF, Benazzo A, Rybin D, Jackson AU, Stringham HM, Song C, Fischer-Rosinsky A, Boesgaard TW, Grarup N, Abbasi FA, Assimes TL, Hao K, Yang X, Lecoeur C, Barroso I, Bonnycastle LL, Böttcher Y, Bumpstead S, Chines PS, Erdos MR, Graessler J, Kovacs P, Morken MA, Narisu N, Payne F, Stancakova A, Swift AJ, Tönjes A, Bornstein SR, Cauchi S, Froguel P, Meyre D, Schwarz PE, Häring HU, Smith U, Boehnke M, Bergman RN, Collins FS, Mohlke KL, Tuomilehto J, Quertemous T, Lind L, Hansen T, Pedersen O, Walker M, Pfeiffer AF, Spranger J, Stumvoll M, Meigs JB, Wareham NJ, Kuusisto J, Laakso M, Langenberg C, Dupuis J, Watanabe RM, Florez JC, Ingelsson E, McCarthy MI, Prokopenko I; MAGIC Investigators. Impact of type 2 diabetes susceptibility variants on quantitative glycemic traits reveals mechanistic heterogeneity. Diabetes. 2014;63:2158-2171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 262] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Valaiyapathi B, Gower B, Ashraf AP. Pathophysiology of Type 2 Diabetes in Children and Adolescents. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2020;16:220-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Anton SD, Moehl K, Donahoo WT, Marosi K, Lee SA, Mainous AG 3rd, Leeuwenburgh C, Mattson MP. Flipping the Metabolic Switch: Understanding and Applying the Health Benefits of Fasting. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2018;26:254-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 377] [Cited by in RCA: 471] [Article Influence: 58.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ramlo-Halsted BA, Edelman SV. The natural history of type 2 diabetes. Implications for clinical practice. Prim Care. 1999;26:771-789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Taylor R. Pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes: tracing the reverse route from cure to cause. Diabetologia. 2008;51:1781-1789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Scheen AJ. Pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes. Acta Clin Belg. 2003;58:335-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Cryer PE, Davis SN, Shamoon H. Hypoglycemia in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1902-1912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 881] [Cited by in RCA: 827] [Article Influence: 36.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Petersen MC, Shulman GI. Mechanisms of Insulin Action and Insulin Resistance. Physiol Rev. 2018;98:2133-2223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1576] [Cited by in RCA: 1964] [Article Influence: 245.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Skyler JS, Bakris GL, Bonifacio E, Darsow T, Eckel RH, Groop L, Groop PH, Handelsman Y, Insel RA, Mathieu C, McElvaine AT, Palmer JP, Pugliese A, Schatz DA, Sosenko JM, Wilding JP, Ratner RE. Differentiation of Diabetes by Pathophysiology, Natural History, and Prognosis. Diabetes. 2017;66:241-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 412] [Cited by in RCA: 444] [Article Influence: 49.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lessan N, Hannoun Z, Hasan H, Barakat MT. Glucose excursions and glycaemic control during Ramadan fasting in diabetic patients: insights from continuous glucose monitoring (CGM). Diabetes Metab. 2015;41:28-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Attum B, Hafiz S, Malik A, Shamoon Z. Cultural Competence in the Care of Muslim Patients and Their Families. 2023 Feb 8. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Ibrahim M, Davies MJ, Ahmad E, Annabi FA, Eckel RH, Ba-Essa EM, El Sayed NA, Hess Fischl A, Houeiss P, Iraqi H, Khochtali I, Khunti K, Masood SN, Mimouni-Zerguini S, Shera S, Tuomilehto J, Umpierrez GE. Recommendations for management of diabetes during Ramadan: update 2020, applying the principles of the ADA/EASD consensus. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2020;8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Albosta M, Bakke J. Intermittent fasting: is there a role in the treatment of diabetes? A review of the literature and guide for primary care physicians. Clin Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;7:3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Pathan MF, Sahay RK, Zargar AH, Raza SA, Khan AK, Ganie MA, Siddiqui NI, Amin F, Ishtiaq O, Kalra S. South Asian Consensus Guideline: Use of insulin in diabetes during Ramadan. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:499-502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kalra S, Aamir AH, Raza A, Das AK, Azad Khan AK, Shrestha D, Qureshi MF, Md Fariduddin, Pathan MF, Jawad F, Bhattarai J, Tandon N, Somasundaram N, Katulanda P, Sahay R, Dhungel S, Bajaj S, Chowdhury S, Ghosh S, Madhu SV, Ahmed T, Bulughapitiya U. Place of sulfonylureas in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus in South Asia: A consensus statement. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2015;19:577-596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Mayfield JA, White RD. Insulin therapy for type 2 diabetes: rescue, augmentation, and replacement of beta-cell function. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70:489-500. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Hassanein M, Echtay AS, Malek R, Omar M, Shaikh SS, Ekelund M, Kaplan K, Kamaruddin NA. Original paper: Efficacy and safety analysis of insulin degludec/insulin aspart compared with biphasic insulin aspart 30: A phase 3, multicentre, international, open-label, randomised, treat-to-target trial in patients with type 2 diabetes fasting during Ramadan. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;135:218-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Garber AJ. Premixed insulin analogues for the treatment of diabetes mellitus. Drugs. 2006;66:31-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Alabbood MH, Ho KW, Simons MR. The effect of Ramadan fasting on glycaemic control in insulin dependent diabetic patients: A literature review. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2017;11:83-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | V RA, Zargar AH. Diabetes control during Ramadan fasting. Cleve Clin J Med. 2017;84:352-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Lessan N, Ezzat Faris M, Assaad-Khalil SH, Ali T. Chapter 3. What happens to the body? Physiology of fasting during Ramadan. In: International Diabetes Federation and DAR International Alliance. Diabetes and Ramadan: Practical Guidelines. International Diabetes Federation and DAR International Alliance; 2021. Apr 24, 2023. [cited 24 April 2023] Available from: https://www.idf.org/our-activities/education/diabetes-and-ramadan/healthcare-professionals.html. |

| 31. | Jabbar A, Hassanein M, Beshyah SA, Boye KS, Yu M, Babineaux SM. CREED study: Hypoglycaemia during Ramadan in individuals with Type 2 diabetes mellitus from three continents. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;132:19-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Abdelrahim D, Faris ME, Hassanein M, Shakir AZ, Yusuf AM, Almeneessier AS, BaHammam AS. Impact of Ramadan Diurnal Intermittent Fasting on Hypoglycemic Events in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials and Observational Studies. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:624423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Ba-Essa EM, Hassanein M, Abdulrhman S, Alkhalifa M, Alsafar Z. Attitude and safety of patients with diabetes observing the Ramadan fast. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;152:177-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Salti I, Bénard E, Detournay B, Bianchi-Biscay M, Le Brigand C, Voinet C, Jabbar A; EPIDIAR study group. A population-based study of diabetes and its characteristics during the fasting month of Ramadan in 13 countries: results of the epidemiology of diabetes and Ramadan 1422/2001 (EPIDIAR) study. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2306-2311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 417] [Cited by in RCA: 481] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Mattoo V, Milicevic Z, Malone JK, Schwarzenhofer M, Ekangaki A, Levitt LK, Liong LH, Rais N, Tounsi H; Ramadan Study Group. A comparison of insulin lispro Mix25 and human insulin 30/70 in the treatment of type 2 diabetes during Ramadan. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2003;59:137-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Cesur M, Corapcioglu D, Gursoy A, Gonen S, Ozduman M, Emral R, Uysal AR, Tonyukuk V, Yilmaz AE, Bayram F, Kamel N. A comparison of glycemic effects of glimepiride, repaglinide, and insulin glargine in type 2 diabetes mellitus during Ramadan fasting. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;75:141-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 37. | Alawadi F, Mohammed K. Bashier A, Rashid F, Chowdhury TA. Chapter 13. Risks of fasting during Ramadan: Cardiovascular, Cerebrovascular and Renal complications. In: International Diabetes Federation and DAR International Alliance. Diabetes and Ramadan: Practical Guidelines. International Diabetes Federation and DAR International Alliance; 2021. Apr 27, 2023. [cited 27 April 2023] Available from: https://www.idf.org/our-activities/education/diabetes-and-ramadan/healthcare-professionals.html.. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 38. | Hamdy O, Mohd Yusof BN, Maher S. Chapter 8. The Ramadan Nutrition Plan (RNP) for people with diabetes. In: International Diabetes Federation and DAR International Alliance. Diabetes and Ramadan: Practical Guidelines. International Diabetes Federation and DAR International Alliance; 2021. May 4, 2023 [cited 4 May 2023] Available from: https://www.idf.org/our-activities/education/diabetes-and-ramadan/healthcare-professionals.html. |

| 39. | Ahmedani MY, Zainudin SB, AlOzairi E. Chapter 7. Pre-Ramadan Assessment and Education. In: International Diabetes Federation and DAR International Alliance. Diabetes and Ramadan: Practical Guidelines. International Diabetes Federation and DAR International Alliance; 2021. May 1, 2023. [cited 1 May 2023] https://www.idf.org/our-activities/education/diabetes-and-ramadan/healthcare-professionals.html. |

| 40. | Cahn A, Miccoli R, Dardano A, Del Prato S. New forms of insulin and insulin therapies for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3:638-652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Tahrani AA, Bailey CJ, Del Prato S, Barnett AH. Management of type 2 diabetes: new and future developments in treatment. Lancet. 2011;378:182-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 419] [Cited by in RCA: 391] [Article Influence: 26.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Campbell JE, Drucker DJ. Pharmacology, physiology, and mechanisms of incretin hormone action. Cell Metab. 2013;17:819-837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 918] [Cited by in RCA: 1119] [Article Influence: 86.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Coskun T, Sloop KW, Loghin C, Alsina-Fernandez J, Urva S, Bokvist KB, Cui X, Briere DA, Cabrera O, Roell WC, Kuchibhotla U, Moyers JS, Benson CT, Gimeno RE, D'Alessio DA, Haupt A. LY3298176, a novel dual GIP and GLP-1 receptor agonist for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: From discovery to clinical proof of concept. Mol Metab. 2018;18:3-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 627] [Article Influence: 78.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Andreadis P, Karagiannis T, Malandris K, Avgerinos I, Liakos A, Manolopoulos A, Bekiari E, Matthews DR, Tsapas A. Semaglutide for type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20:2255-2263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Padda IS, Mahtani AU, Parmar M. Sodium-Glucose Transport Protein 2 (SGLT2) Inhibitors. 2023 May 21. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. [PubMed] |

| 46. | Cannon CP, Pratley R, Dagogo-Jack S, Mancuso J, Huyck S, Masiukiewicz U, Charbonnel B, Frederich R, Gallo S, Cosentino F, Shih WJ, Gantz I, Terra SG, Cherney DZI, McGuire DK; VERTIS CV Investigators. Cardiovascular Outcomes with Ertugliflozin in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1425-1435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 673] [Cited by in RCA: 1092] [Article Influence: 182.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Kerr JL, Timpe EM, Petkewicz KA. Bromocriptine mesylate for glycemic management in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44:1777-1785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | International Diabetes Federation and the DAR International Alliance. Diabetes and Ramadan: Practical Guidelines. Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation 2016. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Al-Arouj M, Bouguerra R, Buse J, Hafez S, Hassanein M, Ibrahim MA, Ismail-Beigi F, El-Kebbi I, Khatib O, Kishawi S, Al-Madani A, Mishal AA, Al-Maskari M, Nakhi AB, Al-Rubean K. Recommendations for management of diabetes during Ramadan. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2305-2311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Bravis V, Hui E, Salih S, Mehar S, Hassanein M, Devendra D. Ramadan Education and Awareness in Diabetes (READ) programme for Muslims with Type 2 diabetes who fast during Ramadan. Diabet Med. 2010;27:327-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Masood SN, Sheikh MA, Masood Y, Hakeem R, Shera AS. Beliefs of people with diabetes about skin prick during Ramadan fasting. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:e68-e69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Ibrahim M, Abu Al Magd M, Annabi FA, Assaad-Khalil S, Ba-Essa EM, Fahdil I, Karadeniz S, Meriden T, Misha'l AA, Pozzilli P, Shera S, Thomas A, Bahijri S, Tuomilehto J, Yilmaz T, Umpierrez GE. Recommendations for management of diabetes during Ramadan: update 2015. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2015;3:e000108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: American College of CHEST Physician.

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gregorio B, Brazil; Park JH, South Korea S-Editor: Qu XL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao S