Published online Aug 16, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i23.5547

Peer-review started: April 22, 2023

First decision: June 12, 2023

Revised: June 17, 2023

Accepted: July 17, 2023

Article in press: July 17, 2023

Published online: August 16, 2023

Processing time: 116 Days and 1.7 Hours

A few reports have revealed induction of rhabdomyolysis by a red yeast rice (RYR) supplement or by RYR in combination with abiraterone (an androgen biosynthesis inhibitor).

A 76-year-old man presented with progressive limb weakness, muscle soreness, and acute kidney injury (AKI). He had been taking the anti-prostate cancer drug abiraterone for 14 mo and had added a RYR supplement 3 mo before symptom onset. After being diagnosed with rhabdomyolysis-induced AKI, the patient discontinued these drugs and responded well to hemodialysis and hemoperfusion. After 23 d of treatment, creatine kinase levels returned to normal and serum creatinine levels decreased.

We speculate that statins, the main lipid-lowering component of RYR, or a combination of statins and abiraterone, will increase the risk of rhabdomyolysis.

Core Tip: In September 2021, a 76-year-old man presented with muscle soreness, limb weakness, and impaired kidney function. He had been taking the anti-prostate cancer drug abiraterone for 14 mo and had added a red yeast rice (RYR) supplement 3 mo before symptom onset. The patient was asked to stop taking these two drugs. He then underwent hemodialysis and hemoperfusion therapy. We measured renal function and muscle damage indicators continuously for 23 d until they returned to normal. The statin content of RYR supplements should be kept in mind, as well as the increased risk of muscle and kidney damage when combined with abiraterone.

- Citation: Wang YH, Zhang SS, Li HT, Zhi HW, Wu HY. Rhabdomyolysis-induced acute kidney injury after administration of a red yeast rice supplement: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(23): 5547-5553

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i23/5547.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i23.5547

Abiraterone is an oral 17α-hydroxylase/C17,20-lyase (CYP17) inhibitor that blocks the production of the testosterone precursor dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA). It was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2012 for the treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). Red yeast rice (RYR) is a dietary supplement for patients with dyslipidemia and is widely consumed by the elderly in most countries[1]. Its main lipid-lowering component, monacolin K (lovastatin), is a 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitor. Lipid-lowering statins, which reduce lipid content in the blood but may impair liver and kidney function or induce muscle damage when in combination with abiraterone, can improve the overall survival of patients with mCRPC[2]. The combined lipid reduction and increased survival in mCRPC are achieved by lowering cholesterol (a DHEA precursor), reducing DHEA transport across cell membranes, and reducing steroid biosynthesis[3]. However, because cytochrome P450 (CYP) is involved in drug metabolism, oral administration of anticancer drugs increases the likelihood of drug–drug interactions. Unlike ketaconazole, an earlier treatment in patients with mCSPC, abiraterone has not been reported to interfere with statin metabolism. However, the present case report suggests that RYR or the RYR–abiraterone interaction may cause rhabdomyolysis.

A 76-year-old man was admitted to the Neurology Department of our hospital on September 9, 2021, because of weakness and pain below the waist for 1 mo and weakness in both arms for 1 wk.

The patient was admitted because of weakness and pain below the waist for 1 mo and weakness in both arms for 1 wk.

The patient had been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus, deep venous thrombosis, and coronary heart disease for over 20 years. He took metformin and betaloc regularly and was injected with aspartic insulin and insulin glargine. The patient had been diagnosed with mCRPC 14 mo previously and treated with abiraterone (1 g/d po QD). Three months earlier, the patient began to take 1.2 g/d of an oral supplement, RYR/ginseng/ginkgo leaf capsules (Shanghai Komen Technology Medicine Co., Ltd.; active ingredient 2000 mg lovastatin per 100 g), thus ingesting ~24 mg/d of lovastatin. The patient's medical history is shown in Figure 1.

Based on a questionnaire survey, no other family members were found to experience similar symptoms.

Limb muscle tenderness (+), proximal and distal muscle strength of the arms (IV), proximal muscle strength of the lower limbs (II), distal muscle strength of the lower limbs (III), bilateral muscle reflex (++), and bilateral tendon reflex (+).

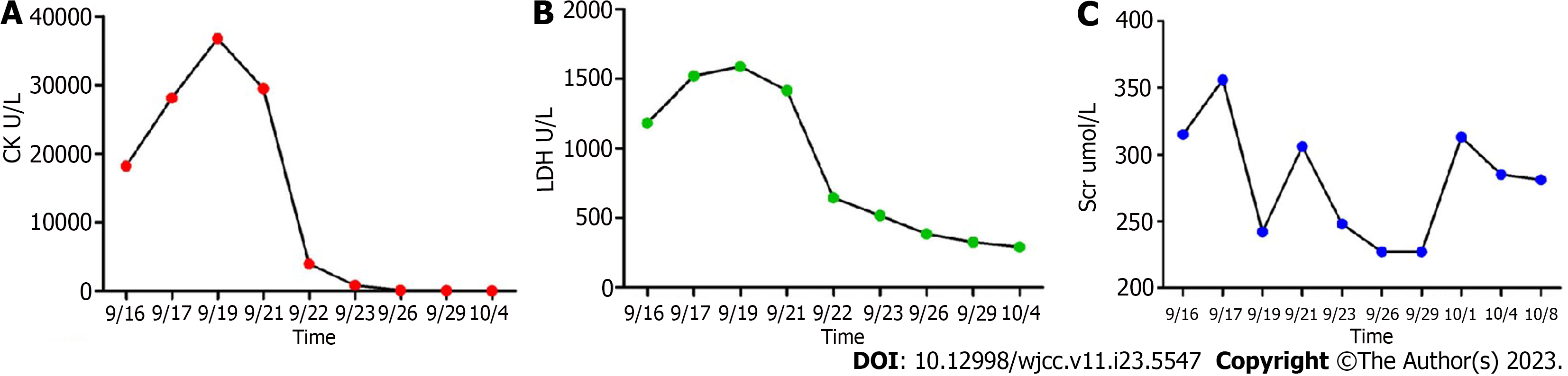

Blood chemical examination (September 16, 2021) revealed: Mild anemia (red blood cell count 3.39 × 1012 L−1; hemoglobin 106 g/L), mild hyponatremia (Na+ 135 mmol/L), elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate 62 mm/h, C-reaction protein (CRP) 105 mg/L, complement C3 (C3) 1.57 g/L, reduced immunoglobulin G 7.71 g/L and immunoglobulin M < 0.181 g/L, elevated transaminases (alanine aminotransferase 643 U/L; aspartate aminotransferase 176 U/L), kidney injury (serum creatinine [Scr] 315 μmol/L), and elevated myocardial enzymes (lactate dehydrogenase [LDH] 1182 U/L; and creatine kinase [CK] 18230 U/L). The cerebrospinal fluid test was normal.

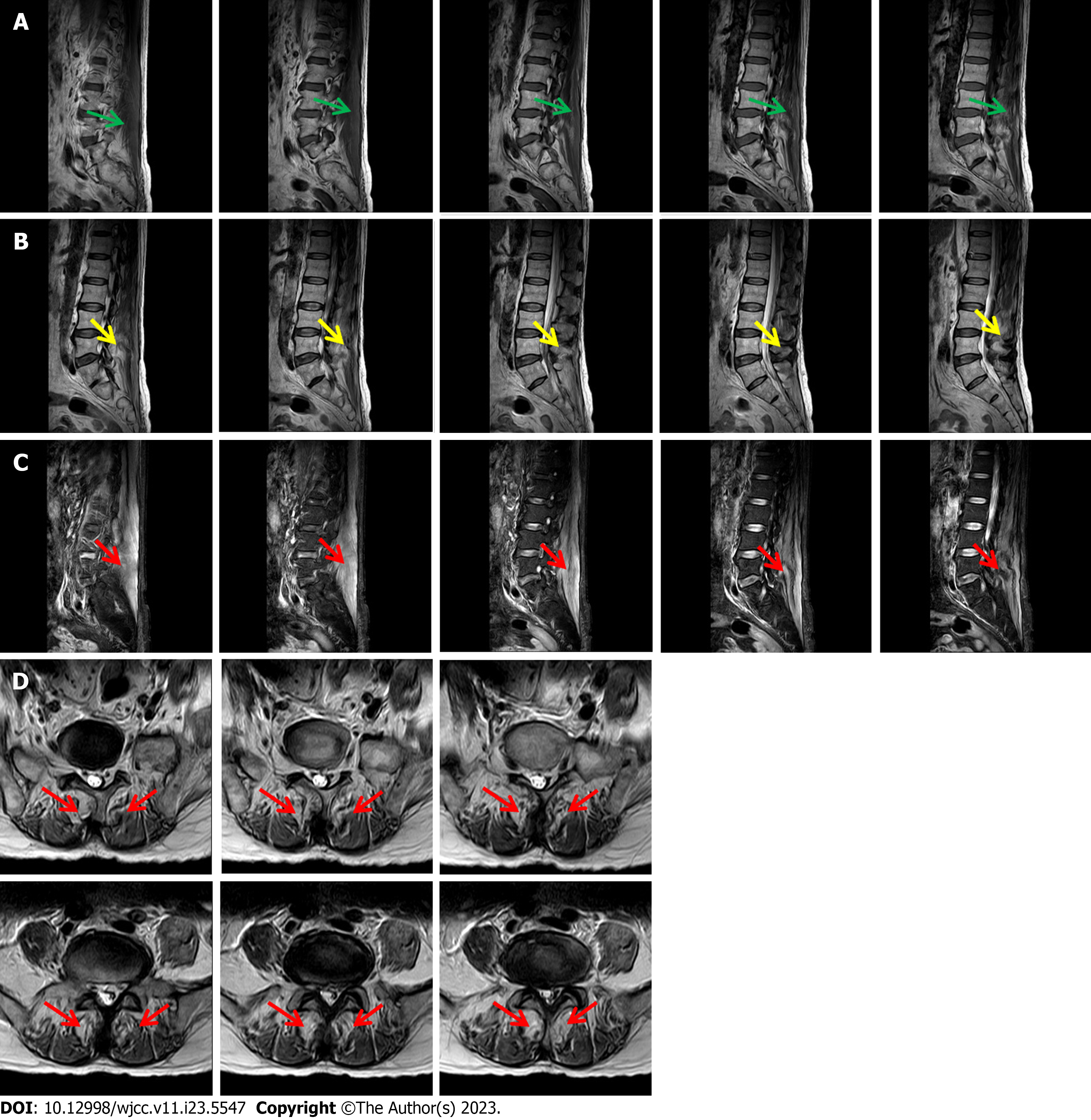

Three-dimensional computed tomography showed degenerative changes in the lumbar spine as well as L2/3 and L3/4 disk bulge. Electromyography showed neurogenic damage of the upper and lower extremities (peripheral nerve damage of the upper and lower extremities involving sensory and motor fibers as well as L5 and S1 Levels). There was no muscle atrophy or tremor; no skin rash on the eyelids, extensor limbs, V-shaped zone of the fore-chest, or shoulder area of the back; and no joint swelling or pain. Magnetic resonance examination revealed diffuse abnormal signals in the erector spinae, with lumbar disc herniation (Figure 2).

Considering the patient’s symptoms, magnetic resonance imaging findings, and progressively increasing CK and Scr levels, rhabdomyolysis-induced acute kidney injury (AKI) was diagnosed. Unfortunately, the patient refused muscle biopsy, so histopathological evidence was not obtained.

Abiraterone and the supplement were discontinued after admission, and other drugs continued to be administered. The patient responded well to hemodialysis, hemoperfusion, ATP disodium injections (40 mg iv drip QD), levocarnitine injection (2 g iv drip QD), Ringer’s fluid (250 mL iv drip QD), sodium bicarbonate tablets (1 g po TID), vitamin B2 (30 mg po TID), and coenzyme Q10 (10 mg po TID). On day 6 of treatment (September 22, 2021), CK levels were significantly reduced. The patient was hospitalized for 23 d. Upon discharge (October 8, 2021), CK levels were normal (93 U/L), LDH levels were close to normal (290 U/L), and Scr levels (281 μmol/L) required continued monitoring. Changes in the patient’s key laboratory indicators are shown in Figure 3.

During hospitalization, no adverse events were observed. The patient received hemodialysis and hemoperfusion every day, tolerated intravenous infusion and oral drug administration well, and was satisfied with the treatment effect. After discharge, the patient resumed all previous medications expect for the RYR supplement. Based on telephonic follow-up, Scr decreased to 190 μmol/L almost 1 mo after discharge, and rhabdomyolysis did not recur. The patient reported no further complaints.

We report a case of AKI caused by drug-induced rhabdomyolysis. Muscle pain and weakness occurred 2 mo after administration of the combination of RYR/ginseng/ginkgo leaf capsules (key ingredient: lovastatin) and abiraterone. Although there have been a few reports of abiraterone-induced rhabdomyolysis[4], the patient did not develop symptoms during the first 11 mo of abiraterone treatment and did not undergo dose adjustment. However, the patient developed progressively aggravated myasthenia and myalgia 2 mo after RYR/ginseng/ginkgo leaf compound supplementation. This supplement contains lovastatin, and the daily oral dose exceeded the recommended dose of 20 mg/d. The patient continued taking an immunosuppressant. No other identifiable specific triggers for rhabdomyolysis (such as decompensated hypothyroidism, liver disease, strenuous exercise, or recreational drugs) were found in the patient’s medical history or physical examination. In addition, abiraterone therapy was well-tolerated after discharge. Therefore, we believe that the AKI caused by rhabdomyolysis in this patient was caused by an overdose of lovastatin or a drug–drug interaction between lovastatin and abiraterone.

Abiraterone is an androgen biosynthesis inhibitor that inhibits DHEA, testosterone, and dihydrotestosterone production by inhibiting the activity of the metabolic enzyme CYP17A1. Therefore, it is suitable for the treatment of mCRPC. Abiraterone has side-effects associated with CYP17A1 inhibition, namely, reduced cortisol secretion, increased adrenocorticoid release, increased corticoid secretion, and hypokalemia, all of which are risk factors for rhabdomyolysis[5]. In a large, real-world cohort study, Japanese researchers tracked the safety and efficacy of abiraterone in combination with prednisone in 492 patients with mCRPC who were followed for 24 mo. No new or unpredictable adverse events were observed in a market-release study of abiraterone[6]. The frequent adverse events observed in the follow-up period were similar to those observed in market-release clinical studies, including hypokalemia (3.0%) and abnormal liver function (6.5%)[6]. Hepatotoxicity was the most common adverse drug reaction. Most patients recovered after abiraterone treatment were discontinued[6]. In our case, however, the patient did not have hypokalemia upon admission, and did not show symptoms of myopathy during the first 11 mo of abiraterone treatment; therefore, we speculate that rhabdomyolysis and AKI were not caused by abiraterone alone.

Although our patient had no clear history of hyperlipidemia, he had been administered lovastatin 3 mo before hospitalization. To date, there have been no reports on rhabdomyolysis or AKI caused by ginseng or ginkgo biloba. Although RYR is a traditional medicinal material that can be used in both medicine and food, and its potential for lowering blood lipids has been demonstrated in numerous studies[7], lovastatin is the main active ingredient among its many chemical components. According to the package insert, lovastatin is present at 2000 mg/100 g RYR. Our patient ingested a 1.2 g capsule per day, equivalent to 24 mg of lovastatin.

Statins prevent cardiovascular diseases by inhibiting HMG-CoA reductase, thus inhibiting cholesterol synthesis, and thereby reducing serum cholesterol levels[2]. There is increasing evidence that statins also play a role in the treatment of cancers, including colon, breast, and prostate cancers[5,7,8]. Laboratory studies have shown that statins can limit cancer progression by promoting apoptosis and inflammatory responses and by inhibiting cancer cell proliferation, adhesion, and angiogenesis[9-12]. A meta-analysis reported that patients with mCRPC may benefit from treatment with abiraterone or enzalutamide in combination with statins[13]. In addition to lowering cholesterol, statins compete to inhibit DHEA uptake by binding to solute carrier transporters (SLCO2B1), thereby effectively reducing the pool of androgens available in tumors. This may explain why statins reduce the incidence of prostate cancer and improve prognosis[9,10].

Furthermore, abiraterone and lovastatin do not exhibit adverse drug–drug interactions in the vast majority of mCRPC patients, and their combined use increases survival and cancer-related mortality in patients with mCRPC[9]. However, in addition to inhibiting cholesterol synthesis, statins can also lead to coenzyme Q10 deficiency, resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction, and thereby inhibiting energy production, reducing cell energy levels, reducing intermediate metabolite synthesis during cholesterol synthesis, affecting the synthesis of important proteins, and reducing the supply of cholesterol to cell membranes[2]. The consequent increase in membrane permeability and instability leads to increased intracellular calcium concentration and cell death. These mechanisms increase the risk of statin-induced rhabdomyolysis[8].

Prior to the development of abiraterone and its approval as an adrenal androgen synthesis inhibitor, patients were treated with ketoconazole, a CYP3A4 inhibitor that causes elevated plasma concentrations of statins and increases the risk of rhabdomyolysis[12]. In contrast, abiraterone acts only on CYP17A1 without significantly affecting statin metabolism. However, in vitro studies have shown that abiraterone metabolites inhibit organic anion transport polypeptide 1B1 (OATP1B1). Theoretically, this transporter affects the uptake of multiple exogenous drugs, including lovastatin. OATP1B1 inhibition increases lovastatin levels, resulting in increased drug toxicity[13,14]. Statin-induced rhabdomyolysis is dose-dependent, especially when statins are used in conjunction with a muscle-toxic agent or drug that can increase their concentration. However, several reports have suggested that interactions between lovastatin and abiraterone cause rhabdomyolysis and AKI[15].

RYR supplements have been found to reduce low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels as effectively as medium-dose statins, and they are a good treatment option for patients who are intolerant to statins. However, the daily dose of lovastatin in RYR supplements and the appropriate dose in combination with abiraterone for patients with mCSPC should be carefully considered. This case highlights the possibility of kidney injury resulting from rhabdomyolysis caused by this drug combination. More attention should be paid to drug–drug interactions in clinical treatment.

We would like to thank Professor Wen-Qiang Cui for his guidance in writing this paper.

| 1. | Yang H, Pan R, Wang J, Zheng L, Li Z, Guo Q, Wang C. Modulation of the Gut Microbiota and Liver Transcriptome by Red Yeast Rice and Monascus Pigment Fermented by Purple Monascus SHM1105 in Rats Fed with a High-Fat Diet. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:599760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Allott EH, Ebot EM, Stopsack KH, Gonzalez-Feliciano AG, Markt SC, Wilson KM, Ahearn TU, Gerke TA, Downer MK, Rider JR, Freedland SJ, Lotan TL, Kantoff PW, Platz EA, Loda M, Stampfer MJ, Giovannucci E, Sweeney CJ, Finn SP, Mucci LA. Statin Use Is Associated with Lower Risk of PTEN-Null and Lethal Prostate Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:1086-1093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Mondul AM, Joshu CE, Barber JR, Prizment AE, Bhavsar NA, Selvin E, Folsom AR, Platz EA. Longer-term Lipid-lowering Drug Use and Risk of Incident and Fatal Prostate Cancer in Black and White Men in the ARIC Study. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2018;11:779-788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Dineen M, Hansen E, Guancial E, Sievert L, Sahasrabudhe D. Abiraterone-induced rhabdomyolysis resulting in acute kidney injury: A case report and review of the literature. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2018;24:314-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Giatromanolaki A, Fasoulaki V, Kalamida D, Mitrakas A, Kakouratos C, Lialiaris T, Koukourakis MI. CYP17A1 and Androgen-Receptor Expression in Prostate Carcinoma Tissues and Cancer Cell Lines. Curr Urol. 2019;13:157-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Koroki Y, Imanaka K, Yasuda Y, Harada S, Fujino A. Safety and efficacy of abiraterone acetate plus prednisolone in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer: a prospective, observational, post-marketing surveillance study. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2021;51:1452-1461. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Zhu B, Qi F, Wu J, Yin G, Hua J, Zhang Q, Qin L. Red Yeast Rice: A Systematic Review of the Traditional Uses, Chemistry, Pharmacology, and Quality Control of an Important Chinese Folk Medicine. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:1449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gluba-Brzozka A, Franczyk B, Toth PP, Rysz J, Banach M. Molecular mechanisms of statin intolerance. Arch Med Sci. 2016;12:645-658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Anderson-Carter I, Posielski N, Liou JI, Khemees TA, Downs TM, Abel EJ, Jarrard DF, Richards KA. The impact of statins in combination with androgen deprivation therapyin patients with advanced prostate cancer: A large observational study. Urol Oncol. 2019;37:130-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Schnoeller TJ, Jentzmik F, Schrader AJ, Steinestel J. Influence of serum cholesterol level and statin treatment on prostate cancer aggressiveness. Oncotarget. 2017;8:47110-47120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gordon JA, Buonerba C, Pond G, Crona D, Gillessen S, Lucarelli G, Rossetti S, Dorff T, Artale S, Locke JA, Bosso D, Milowsky MI, Witek MS, Battaglia M, Pignata S, Cherhroudi C, Cox ME, De Placido P, Ribera D, Omlin A, Buonocore G, Chi K, Kollmannsberger C, Khalaf D, Facchini G, Sonpavde G, De Placido S, Eigl BJ, Di Lorenzo G. Statin use and survival in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with abiraterone or enzalutamide after docetaxel failure: the international retrospective observational STABEN study. Oncotarget. 2018;9:19861-19873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Potter GA, Barrie SE, Jarman M, Rowlands MG. Novel steroidal inhibitors of human cytochrome P45017 alpha (17 alpha-hydroxylase-C17,20-lyase): potential agents for the treatment of prostatic cancer. J Med Chem. 1995;38:2463-2471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 293] [Cited by in RCA: 295] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Wagner JB, Ruggiero M, Leeder JS, Hagenbuch B. Functional Consequences of Pravastatin Isomerization on OATP1B1-Mediated Transport. Drug Metab Dispos. 2020;48:1192-1198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Desikan SP, Sobash P, Fisher A, Desikan R. Statin-Induced Rhabdomyolysis Due to Pharmacokinetic Changes From Biliary Obstruction in a Patient With Metastatic Prostate Cancer. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2020;8:2324709620947275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Elam MB, Majumdar G, Mozhui K, Gerling IC, Vera SR, Fish-Trotter H, Williams RW, Childress RD, Raghow R. Patients experiencing statin-induced myalgia exhibit a unique program of skeletal muscle gene expression following statin re-challenge. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0181308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 573] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medical informatics

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Sangani V, United States; Tang F, China S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Cai YX