Published online Jul 26, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i21.5160

Peer-review started: May 9, 2023

First decision: June 13, 2023

Revised: June 14, 2023

Accepted: July 3, 2023

Article in press: July 3, 2023

Published online: July 26, 2023

Processing time: 79 Days and 0.6 Hours

Large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) is an uncommon type of tumor that can occur in the endometrium. This aggressive cancer requires definitive management. Here, we describe the clinical characteristics and treatment of a postmenopausal woman with large cell NEC of the endometrium.

A 55-year-old Asian female presented with a 1-year history of postmenopausal vaginal bleeding. Transvaginal ultrasound revealed a thickened endometrium (30.2 mm) and a hypervascular tumor. Computed tomography revealed that the tumor had invaded more than half of the myometrium and spread to the pelvic lymph nodes. The tumor marker, carcinoembryonic antigen, was elevated (3.65 ng/mL). Endocervical biopsy revealed high-grade endometrial carcinoma. She underwent radical hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, omentectomy, and bilateral pelvic and para-aortic lymph node dissection. Pathological exami

We report the characteristics and successful management of a rare case of large-cell endometrial NEC concomitant with Lynch syndrome.

Core Tip: Here, we report a case of large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) of the endometrium. We have updated information on NEC regarding its symptoms, signs, diagnosis, and treatment. Due to the rarity of endometrial NEC, we provide a strategy for diagnosing and treating this type of endometrial cancer.

- Citation: Siu WYS, Hong MK, Ding DC. Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the endometrium concomitant with Lynch syndrome: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(21): 5160-5166

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i21/5160.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i21.5160

Large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) of the endometrium is a rare type of tumor. To date, approximately 150 cases of endometrial NECs have been reported[1]. Only 21 cases of large cell endometrial NECs have been previously pub

Endometrial NEC can present with symptoms such as vaginal bleeding, pelvic pain, and abdominal swelling[3]. It is more common in postmenopausal women but can also affect younger women. NEC of the endometrium can be difficult to diagnose and requires tumor biopsy[4]. Pathological examination revealed neuroendocrine and endometrioid adenocarcinoma components. Immunohistochemistry can be used to confirm the diagnosis, as tumor cells express neuroendocrine markers such as CD56, chromogranin A, and synaptophysin[3]. The tumor is typically high grade, with a high mitotic rate and Ki-67 proliferation index[3]. The prognosis of NEC of the endometrium is poor[5,6].

Lynch syndrome is characterized by germline mutation in four mismatch repair genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2)[7]. Family members of patients with Lynch syndrome ultimately develop colon or endometrial cancers. In patients with endometrial cancer, Lynch syndrome is found in 2.5% of all patients. The mean age at diagnosis of Lynch syndrome in patients with endometrial cancer is 48-62 years. The inheritance type of Lynch syndrome is inherited in an autosomal-dominant manner. A family history of colon or endometrial cancer should be considered in the differential diagnosis of Lynch syndrome[7].

Treatment options include surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy; however, the optimal management of this type of cancer is not well established[8]. The prognosis is generally poor with a high risk of recurrence and metastasis[2].

Given the rarity of large-cell NEC in the endometrium in patients with Lynch syndrome, we present a case report of a woman with this condition and her clinical characteristics.

A 55-year-old female without any underlying diseases initially presented to our clinic due to postmenopausal bleeding for 1 year.

She was in her usual state of health until 1 year ago when she noted abnormal vaginal spotting. The patient used two to three pads per day. She visited a local clinic, and a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug was prescribed. However, the symptoms did not improve. Subsequently, the patient visited another hospital. The tumors were found in the en

She experienced menarche at the age of 13 years. She had experienced menopause 5 years previously. She had four children, all of whom were through vaginal delivery. No history of hypertension, diabetes, or thyroid disease. The patient had a history of appendectomy.

Her father had a history of colon cancer, a cardiovascular accident, and hypertension. The patient’s sister also had a history of colon cancer.

Pelvic examination revealed bleeding from a papillary tumor in the cervix and vaginal discharge without malodor. No lifting pain or tenderness was noted in the bilateral adnexal region.

Her height and weight were 150 cm and 53 kg, respectively. Her blood pressure was 135/101 mmHg and pulse rate was 80 bpm. The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group score was 1.

Serum CA 125, CA19-9, and SCCA were obtained with levels 27.2 U/mL (normal value: 35 U/mL), 15.1 U/mL (normal value: 35 U/mL), and 0.9 ng/mL (normal value: 1.5 ng/mL), respectively. Carcinoembryonic antigen was elevated (3.65 ng/mL, normal: 1.5 ng/mL). Leukocytosis of 19060 with left shift (neutrophil segment 87.4%) was also noted. Normal hemoglobin (13.4 g/dL) and platelet levels (340000/uL) were noted.

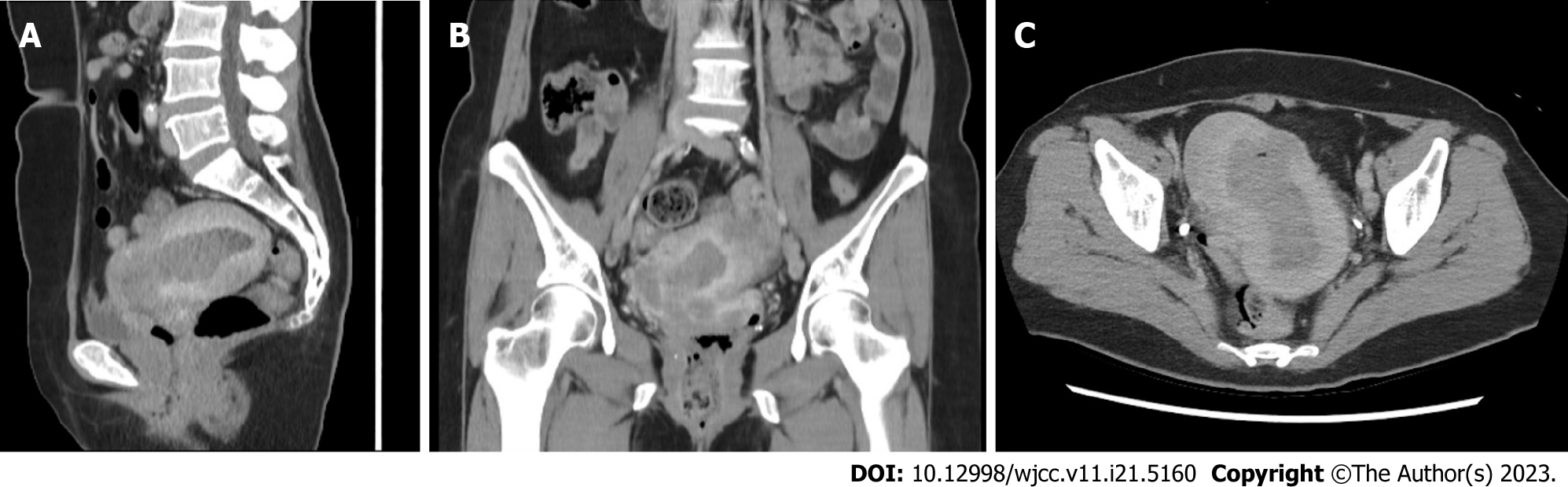

Transvaginal ultrasonography revealed a retroverted enlarged uterus with a thickened endometrium (30.2 mm and a hypervascular tumor within the intrauterine cavity (Figure 1). The left ovary was 3.9 cm in size with an irregular border. A 5.2 cm right adnexal mass was also noted. Computed tomography revealed a tumor 6.1 cm in diameter that had invaded more than 1/2 of the uterine myometrium, stromal connective tissue of the cervix, serosa, adnexa, parametrium, and bowel (Figure 2). Regional metastases were observed in the right and left external iliac lymph nodes. Cystoscopy revealed no tumor invasion into the bladder mucosa. Colonoscopy revealed no tumor invasion.

Mixed large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (80%), endometrioid adenocarcinoma (20%), pT2N0M0 grade 3, and International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics stage 2 adenocarcinoma were diagnosed.

The patient underwent type 3 radical hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, omentectomy, and bilateral pelvic and para-aortic lymph node dissections. The gross specimen revealed a polypoid tumor lesion measuring 8.5 cm over the endometrium, extending into the cervix and invading the deep myometrium to one-half or more of the myometrial thickness.

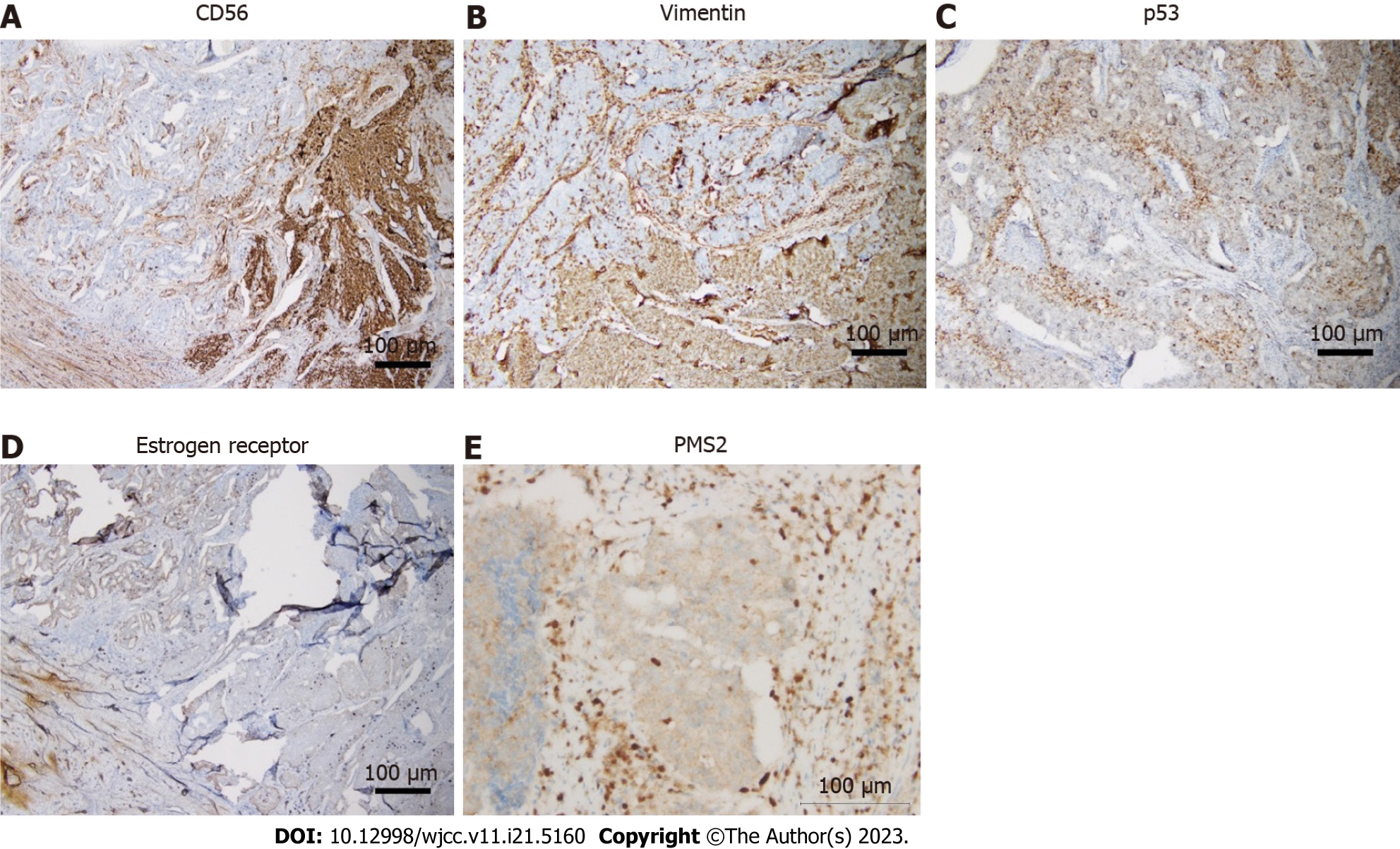

Histopathology revealed mixed large-cell NEC (80%) and endometrioid adenocarcinoma (20%). The tumor had metastasized to the uterine cervix and invaded more than half the thickness of the myometrium. A leiomyoma measuring 5.5 cm in size was also observed. The bilateral fallopian tubes and ovaries were involved in the tumor. The histological grade was grade 3 for NEC and grade 2 for endometrioid adenocarcinoma. Lymphovascular invasion was also observed. The pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes had not metastasized. Immunohistochemistry of the tumor was positive for unfolded estrogen receptor (moderate +, 20%), progesterone receptor (moderate +, 1%), CD56 (focal +), vimentin (focal +), p53 (+, wild type), ki67 (+, 90%), and malignant hyperthermia susceptibility 6 (MHS6, intact), and negative for p63, p16, chromogranin, and synaptophysin and PMS2 (loss of nuclear staining) (Figure 3).

Postoperatively, adjuvant chemotherapy with etoposide (50 mg/m2 on days 1 and 2) and cisplatin (40 mg/m2 on day 1) was administered for five cycles with a 3-wk interval. Mild hair loss, dizziness, and taste loss were observed after chemotherapy. Gastrointestinal discomfort was noted for 2 d after chemotherapy.

No recurrence was noted at 5 mo postoperatively. Tumor markers within normal limits were noted 3 mo postoperatively.

Neuroendocrine tumors are rare and originate from cells of the neuroendocrine lineage[9]. Large cell NEC is a subtype of high-grade NEC with aggressive behaviors. The thorax is the most common site for large-cell NEC. However, it can also occur in the gynecological tract. A previous review included 13 patients with large-cell NEC of the uterus; the median age was 71 years, and most had stage III/IV disease[9]. The most common symptoms of endometrial NEC are postmenopausal vaginal bleeding and lower abdominal pain[3,4,9].

Diagnosis depends on the pathological diagnosis. The morphology of large-cell NEC of the endometrium is large-cell carcinoma with neuroendocrine growth patterns, such as organoid nesting, trabeculae, or rosettes[9]. Immunohistochemistry has revealed NEC-expressing neuroendocrine biomarkers, such as synaptophysin, chromogranin, and CD56[4,10]. However, these immunohistochemical markers have been reported to have high sensitivity and low specificity[3]. Therefore, it may be challenging to diagnose large-cell NEC, where false-positive results may occur. High-grade NEC usually stains negatively for chromogranin, a sensitive marker for low-grade NEC[11]. In our case, the tumor only expressed CD56 but showed negative staining for synaptophysin and chromogranin.

The patient’s father and sister both had colon cancer. She also showed a loss of PMS2 expression. This indicated that she had Lynch syndrome. Lynch syndrome is characterized by germline mutation in four mismatch repair genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2)[7]. During DNA replication, mismatch repair genes repair incorrect nucleotide base pairs. If this condition is not repaired, the encoded proteins may form oncoproteins, causing oncogenesis[12]. Usually, Lynch syndrome can be diagnosed or screened by immunostaining the four mismatch repair (MMR) proteins of the tumor tissue or microsatellite instability (MSI) testing[13]. The prevalence of Lynch syndrome is 2.5% of all endometrial cancers. The mean age at diagnosis of Lynch syndrome in patients with endometrial cancer is 48-62 years. Examination of the endometrium and ovary included pelvic examination, transvaginal ultrasound, endometrial biopsy, and CA125 levels. Hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is recommended when childbearing is completed[7].

Previous studies have indicated that p53 mutations may be present in neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) of the endometrium[4,14,15]. p53 mutation in neuroendocrine carcinoma refers to a specific genetic alteration involving the p53 gene, which plays a critical role in regulating cell growth and preventing the formation of tumors. In normal circumstances, the p53 gene acts as a tumor suppressor gene, helping to prevent the development and progression of cancer. However, mutations in the p53 gene can disrupt its normal function, leading to the formation of tumors, including neuroendocrine carcinoma. In neuroendocrine carcinoma, p53 mutations can contribute to the uncontrolled growth and spread of neuroendocrine cells, leading to the development of aggressive and potentially metastatic tumors. In our case, the expression of wild-type p53 was observed.

Due to the rarity of this cancer, there are still no large series on direct management. The consensus favors treatment with staging surgery comprising hysterectomy, bilateral adnexectomy, and lymph node dissection, followed by adjuvant chemotherapy with etoposide and platinum-based agents[3].

No published case report has described neoadjuvant chemotherapy for large-cell NEC of the endometrium. If the performance status allows, it might be helpful to administer neoadjuvant chemotherapy; however, more studies are needed in this respect. However, a standard treatment regimen remains to be established.

No standard chemotherapy regimen has been reported, and most cases are from small-cell NEC of the lungs[16]. A previous study showed that of 10 patients with NEC who received chemotherapy, seven received etoposide and cisplatin, and three received irinotecan and cisplatin[2]. Another study included 25 patients with NEC of the endometrium; all patients underwent surgery, and 15 received adjuvant chemotherapy[3]. Most of these studies used platinum-based regimens. A study included 16 patients, of whom eight received chemotherapy[4]. Most of these studies used cisplatin and etoposide. Nevertheless, cisplatin and irinotecan have been suggested as the best regimen for treating high-grade pulmonary NEC in a phase III trial[17]. Topotecan, cyclophosphamide/doxorubicin/vincristine, and irinotecan/platinum are used for 2nd line therapy[15,16]. Radiotherapy also can be used as an adjuvant therapy[4,16]. A previous case report used a regimen of liposome paclitaxel (240 mg) and lobaplatin (50 mg) for four cycles with a 3-wk interval; the patient survived for 15 mo[5]. In our case, chemotherapy with cisplatin and etoposide was prescribed. The patient’s tumor marker levels have been within normal limits since chemotherapy.

The disease course has been found to be aggressive in early-stage endometrial NEC, with rapid recurrence. The prognostic factors for endometrial NEC include surgery, lymph node metastasis, and chemotherapy[18]. Among the 20 cases reported in the 2019 study, 0 cases of recurrence-free survival at 3 years were reported. Only one case reported no evidence of disease at 20 mo; up to 10 patients died, and 11 cases of death were reported[2]. Another study included 25 patients, 12 of whom died from the disease, with a mean survival of 12.3 mo[3]. Eleven patients were alive 5-134 mo after diagnosis (seven survived for > 5 years)[3]. The 5-year survival rate was 28%[3,18]. Another study included 16 patients with large-cell NEC of the endometrium; seven patients died, with a median survival of 10 mo[4]. Another nine patients were alive, with a median survival of 9 mo[4]. A previous study included 13 patients; six died (median survival: 7.5 mo), and seven were alive (median survival: 10.5 mo)[9]. A previous study recruited 12 patients with large-cell NEC of the endometrium; eight died (median survival: 5 mo), and four were alive (median survival: 12 mo)[5]. Overall, the prognosis and survival of patients with NEC of the endometrium is poor. In our case, the patient is currently undergoing chemotherapy at 5 mo post-diagnosis.

Here, we report a case of large-cell NEC of the endometrium concomitant with Lynch syndrome. Large-cell NEC of the endometrium is a rare and aggressive cancer for which definitive adjuvant chemotherapy guidelines are yet to be established. Vaginal bleeding and lower abdominal pain are the most common presenting symptoms. NEC was diag

We thank Dr. Chiu-Hsuan Cheng for her assistance for pathological pictures.

| 1. | Akgor U, Kuru O, Sakinci M, Boyraz G, Sen S, Cakır I, Turan T, Gokcu M, Gultekin M, Sayhan S, Salman C, Ozgul N. Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the endometrium: A very rare gynecologic malignancy. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2021;50:101897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jenny C, Kimball K, Kilgore L, Boone J. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the endometrium: a report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2019;28:96-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Pocrnich CE, Ramalingam P, Euscher ED, Malpica A. Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of the Endometrium: A Clinicopathologic Study of 25 Cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:577-586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tu YA, Chen YL, Lin MC, Chen CA, Cheng WF. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the endometrium: A case report and literature review. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;57:144-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Du R, Jiang F, Wang ZY, Kang YQ, Wang XY, Du Y. Pure large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma originating from the endometrium: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2021;9:3449-3457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zhan H, Mojica W, Chen F. Primary Large Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of the Uterus: A Case Report and Literature Review. N Am J Med Sci [Internet] 2018; 11. Available from: https://www.najms.com/index.php/najms/article/viewFile/518/534. . |

| 7. | Duraturo F, Liccardo R, De Rosa M, Izzo P. Genetics, diagnosis and treatment of Lynch syndrome: Old lessons and current challenges. Oncol Lett. 2019;17:3048-3054. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhang J, Pang L. Primary Neuroendocrine Tumors of the Endometrium: Management and Outcomes. Front Oncol. 2022;12:921615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Burkeen G, Chauhan A, Agrawal R, Raiker R, Kolesar J, Anthony L, Evers BM, Arnold S. Gynecologic large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma: A review. Rare Tumors. 2020;12:2036361320968401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hiroshima K, Mino-Kenudson M. Update on large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2017;6:530-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Shahabi S, Pellicciotta I, Hou J, Graceffa S, Huang GS, Samuelson RN, Goldberg GL. Clinical utility of chromogranin A and octreotide in large cell neuro endocrine carcinoma of the uterine corpus. Rare Tumors. 2011;3:e41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pećina-Šlaus N, Kafka A, Salamon I, Bukovac A. Mismatch Repair Pathway, Genome Stability and Cancer. Front Mol Biosci. 2020;7:122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 31.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yurgelun MB, Hampel H. Recent Advances in Lynch Syndrome: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Cancer Prevention. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38:101-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Nguyen ML, Han L, Minors AM, Bentley-Hibbert S, Pradhan TS, Pua TL, Tedjarati SS. Rare large cell neuroendocrine tumor of the endometrium: A case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4:651-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Makihara N, Maeda T, Nishimura M, Deguchi M, Sonoyama A, Nakabayashi K, Kawakami F, Itoh T, Yamada H. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma originating from the uterine endometrium: a report on magnetic resonance features of 2 cases with very rare and aggressive tumor. Rare Tumors. 2012;4:e37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Matsumoto H, Nasu K, Kai K, Nishida M, Narahara H, Nishida H. Combined large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma and endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the endometrium: A case report and survey of related literature. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2016;42:206-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Eba J, Kenmotsu H, Tsuboi M, Niho S, Katayama H, Shibata T, Watanabe S, Yamamoto N, Tamura T, Asamura H; Lung Cancer Surgical Study Group of the Japan Clinical Oncology Group; Lung Cancer Study Group of the Japan Clinical Oncology Group. A Phase III trial comparing irinotecan and cisplatin with etoposide and cisplatin in adjuvant chemotherapy for completely resected pulmonary high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma (JCOG1205/1206). Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2014;44:379-382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Pang L, Chen J, Chang X. Large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the gynecologic tract: Prevalence, survival outcomes, and associated factors. Front Oncol. 2022;12:970985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Obstetrics and gynecology

Country/Territory of origin: Taiwan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Grawish ME, Egypt; Lim SC, South Korea S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH