Published online May 16, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i14.3317

Peer-review started: February 4, 2023

First decision: March 24, 2023

Revised: March 31, 2023

Accepted: April 12, 2023

Article in press: April 12, 2023

Published online: May 16, 2023

Processing time: 100 Days and 15.2 Hours

Rectal prolapse occurs most commonly in children and middle-aged and elderly women and is relatively rare in young men and is occasionally caused by bladder stones. Severe rectal prolapse, bilateral hydronephrosis, and renal insufficiency caused by bladder stones are rare in a 30-year-old man.

We report the case of a 30-year-old male patient with cerebral palsy who presented with a large bladder stone that resulted in severe rectal prolapse, bilateral hydronephrosis, and renal insufficiency. Following a definitive diag

Rectal prolapse is a rare clinical manifestation of bladder stones, particularly in young adults. Cerebral palsy patients are a vulnerable group in society because of their intellectual disabilities and communicative impairments. Accordingly, besides taking care of their daily diet, abnormal signs in their bodies should receive the doctors’ attention in a timely manner.

Core Tip: Bladder stones are generally observed in elderly males and children but are rarely found in young adults. Similarly, rectal prolapse is extremely rare in young men. Clinically, the most common symptoms of bladder stones are urinary frequency, interrupted urine flow, typically terminal hematuria, dysuria, or suprapubic pain, which are worst at the end of urination. Rectal prolapse is a rare clinical manifestation of bladder stones. We report an unusual case of a young man with cerebral palsy who presented with rectal prolapse and finally confirmed a diagnosis of bladder stone. Patients with cerebral palsy are unable to accurately describe physical discomfort due to intellectual disability and commu

- Citation: Ding HX, Huang JG, Feng C, Tai SC. Rectal prolapse in a 30-year-old bladder stone male patient: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(14): 3317-3322

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i14/3317.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i14.3317

Bladder stones constitute approximately 5% of all urinary tract stones[1]. They are generally observed in elderly males and children and are rarely found in young adults[2-4]. The most common symptoms of bladder stones are urinary frequency, interrupted urine flow, typically terminal hematuria, dysuria, or suprapubic pain, which are worst at the end of urination. These symptoms may be exacerbated following sudden movement and exercise[5,6]. In addition to dysuria, children may experience pulling of the penis, urinary retention, enuresis, or rectal prolapse. Bladder stones are incidental findings in 10% of cases[7,8]. Bladder stone presentations are often due to interrupted urination, dysuria, or gross hematuria. Rectal prolapse is an extremely rare reason for a doctor’s visit for bladder stones in young adults. Here, we report the case of a 30-year-old male patient.

A 30-year-old male patient with cerebral palsy presented to the emergency department with a history of recurrent rectal prolapse for one year and a six-hour failed manual reduction procedure.

The symptoms started one year before presentation with recurrent rectal prolapse. When rectal prolapse had occurred, the patient had shown obvious irritability and painful expressions. The obvious irritability and painful expressions could be relieved after manual reduction. Six hours before admission, the patient developed rectal prolapse. Because of a failed manual reduction procedure, he was brought to the emergency department of our hospital, accompanied by a doctor of his welfare home.

The patient had typical clinical manifestations of cerebral palsy, including central motor disorders, abnormal posture, intellectual disability, communicative impairments, and abnormal mental behavior. He could walk only short distances, spent most of his time sitting or resting in bed, and his emotional changes could only be guessed through facial expressions.

The patient’s family history was unknown because he was abandoned in an orphanage after being diagnosed with cerebral palsy in infancy.

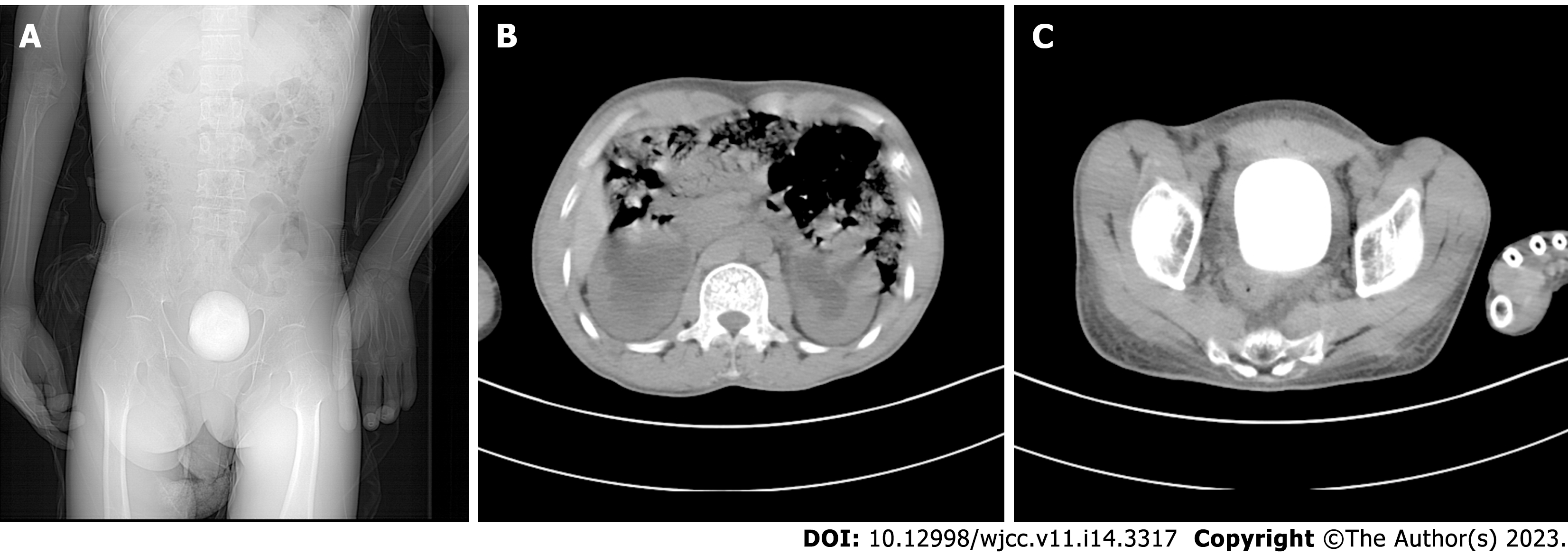

On physical examination, his body mass index (BMI), calculated from 145 cm of height and 35 kg of weight, was 16.6 kg/m2. A palpable mass in the bladder area of the lower abdomen demonstrated marked tenderness, and the rectum was prolapsed approximately 10 cm from the anus (Figure 1).

Blood biochemical analysis indicated a potassium level of 2.443 mmol/L, creatinine levels of 381 µmol/L, and blood urea nitrogen of 11.53 mmol/L.

Abdominal computed tomography revealed a large bladder stone, bilateral hydronephrosis, and thickening of the bladder wall (Figure 2).

Bladder stone, rectal prolapse.

The anorectal surgeon manually reset the prolapsed rectum, and the patient was referred to the urology department for treatment. After the patient’s hypokalemia was corrected and nutritional support was provided, we performed a cystotomy and excised the bladder stone. We analyzed the components of the bladder stone and found that the main components were ammonium uric acid and calcium oxalate.

One week after the operation, the patient’s catheter was removed, and he returned to normal urination. The renal function and serum potassium were normal upon reexamination. The patient with rectal prolapse underwent surgery in the proctology department.

Bladder stones are rare causes of rectal prolapse. In the past few decades, only four papers have reported rectal prolapse caused by bladder stones. Among them, three cases were of primary bladder stones in infants and young children[9-11], and one case was of secondary bladder stones caused by foreign bodies in an adult’s bladder[12]. There have been no reports of bladder stones as the primary cause of rectal prolapse in adults. This study reports a patient aged 30 years without prior history of benign prostatic hyperplasia, whose large bladder stone led to severe rectal prolapse, bilateral hydronephrosis, and renal insufficiency.

Rectal prolapse mostly occurs in children, middle-aged, and elderly women and is generally related to an increase in abdominal pressure (such as constipation), chronic cough, difficulty in urinating, or multiple deliveries, which often leads to increased abdominal pressure and pushes the rectum to prolapse downward[13]. Rectal prolapse is rarer in men than it is in women. Some theories suggest that the prostate is a powerful anchor for the pelvic organ and may also be associated with low-frequency constipation[14]. In this patient, dysuria due to bladder stones was a probable cause, accompanied by a persistent increase in the abdominal pressure required to urinate, ultimately leading to rectal prolapse. Additionally, the prolapsed rectum, pulling the floor of the bladder may have caused chronic, incomplete bladder emptying, favoring urine residue and stone formation. They affect each other, leading to a vicious circle.

In recent decades, the incidence of bladder stones has decreased annually[15]. Bladder stones are usually multi-factorial in etiology[3] and are classified as primary, secondary, or migratory[16]. Primary or endemic bladder stones are usually observed in children in areas with poor hydration, recurrent diarrhea, and a diet deficient in animal protein without any other urinary tract pathology[7]. Secondary bladder stones are most commonly caused by bladder outlet obstruction in adults, accounting for 45%–79% of bladder stones. They are also associated with neurogenic bladder dysfunction, chronic bacteriuria, foreign bodies, catheters, bladder diverticula, bladder augmentation, and urinary diversion[3,5,6,17,18]. The term “migratory” refers to stones that have left the upper urinary tract after forming and may serve as a site for bladder stone growth once they have passed[19]. It was necessary to analyze the etiology of the patient’s bladder stone; its composition was mainly ammonium acid urate and calcium oxalate, which is consistent with research findings on bladder stones caused by malnutrition[20]. Furthermore, the patient’s BMI of 16.6 indicated a poor nutritional state. Thus, the stone formation in the patient was due to malnutrition and low water intake but was also aggravated by secondary urinary tract infection after stone formation.

It is also likely that rectal prolapse and bladder stones are two separate pathologies. The patient had cerebral palsy and could have been prone to chronic constipation as an underlying risk factor for rectal prolapse. However, the outcome of the disease is often not caused by a single factor; therefore it is necessary to consider whether there is an interaction between pathogenic factors when studying the pathogenic mechanism.

The patient was diagnosed with cerebral palsy and was unable to live independently. Residing in a welfare home, he could not express his physical discomfort clearly. In the early stage of rectal prolapse, the patient had abnormal physical signs, but the doctors did not notice them promptly, and he did not receive treatment until severe rectal prolapse occurred one year later. It is possible that the doctors in the welfare home did not conduct a comprehensive evaluation of the patient, which may have accounted for the delayed diagnosis and treatment. However, patients with cerebral palsy are a vulnerable group in society and deserve special attention.

Bladder stones are a rare cause of rectal prolapse, particularly in young adults. In this case, the diagnosis and treatment were delayed because of the patient’s cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, and communication impairment. Patients with cerebral palsy are a vulnerable group in society and deserve particular attention. Accordingly, besides taking care of their daily diet, clinicians should be keenly aware of any abnormal signs in the patient’s body and make timely diagnoses and treatments.

We acknowledge the contribution of the participants. We thank Home for Researchers editorial team (www.home-for-researchers.com) for language editing service.

| 1. | Aydogdu O, Telli O, Burgu B, Beduk Y. Infravesical obstruction results as giant bladder calculi. Can Urol Assoc J. 2011;5:E77-E78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Halstead SB. Epidemiology of bladder stone of children: precipitating events. Urolithiasis. 2016;44:101-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Takasaki E, Suzuki T, Honda M, Imai T, Maeda S, Hosoya Y. Chemical compositions of 300 Lower urinary tract calculi and associated disorders in the urinary tract. Urol Int. 1995;54:89-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Naqvi SA, Rizvi SA, Shahjehan S. Bladder stone disease in children: clinical studies. J Pak Med Assoc. 1984;34:94-101. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Smith JM, O'Flynn JD. Vesical stone: The clinical features of 652 cases. Ir Med J. 1975;68:85-89. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Millán-Rodríguez F, Errando-Smet C, Rousaud-Barón F, Izquierdo-Latorre F, Rousaud-Barón A, Villavicencio-Mavrich H. Urodynamic findings before and after noninvasive management of bladder calculi. BJU Int. 2004;93:1267-1270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lal B, Paryani JP, Memon SU. Childhood bladder stones-an endemic disease of developing countries. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2015;27:17-21. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Al-Marhoon MS, Sarhan OM, Awad BA, Helmy T, Ghali A, Dawaba MS. Comparison of endourological and open cystolithotomy in the management of bladder stones in children. J Urol. 2009;181:2684-7; discussion 2687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Liu J. One Case Report of Bladder Stone Complicated with Prolapse of Anus in Children. Jiangxi Medical Journal. 1982;6:64-64. |

| 10. | Munns J, Amawi F. A large urinary bladder stone: an unusual cause of rectal prolapse. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95:1026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lauschke H. Large urinary bladder stones associated with prolapse of the rectum in children: case report. Trop Doct. 1989;19:65-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chi J, Guo Z. [A case report of rectal prolapse caused by bladder stones]. Gong Qi Yi Kan 1995; 2: 87-87. |

| 13. | Goldstein SD, Maxwell PJ 4th. Rectal prolapse. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2011;24:39-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Church J. Rectal Prolapse: Diagnosis and Clinical Management. Gastroenterology 2009; 136: 1456-1457. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Ye Z, Zeng G, Yang H, Li J, Tang K, Wang G, Wang S, Yu Y, Wang Y, Zhang T, Long Y, Li W, Wang C, Wang W, Gao S, Shan Y, Huang X, Bai Z, Lin X, Cheng Y, Wang Q, Xu Z, Xie L, Yuan J, Ren S, Fan Y, Pan T, Wang J, Li X, Chen X, Gu X, Sun Z, Xiao K, Jia J, Zhang Q, Sun T, Xu C, Shi G, He J, Song L, Sun G, Wang D, Liu Y, Han Y, Liang P, Wang Z, He W, Chen Z, Xing J, Xu H. The status and characteristics of urinary stone composition in China. BJU Int. 2020;125:801-809. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Philippou P, Moraitis K, Masood J, Junaid I, Buchholz N. The management of bladder lithiasis in the modern era of endourology. Urology. 2012;79:980-986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Douenias R, Rich M, Badlani G, Mazor D, Smith A. Predisposing factors in bladder calculi. Review of 100 cases. Urology. 1991;37:240-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yang X, Wang K, Zhao J, Yu W, Li L. The value of respective urodynamic parameters for evaluating the occurrence of complications linked to benign prostatic enlargement. Int Urol Nephrol. 2014;46:1761-1768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Childs MA, Mynderse LA, Rangel LJ, Wilson TM, Lingeman JE, Krambeck AE. Pathogenesis of bladder calculi in the presence of urinary stasis. J Urol. 2013;189:1347-1351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Salah MA, Holman E, Khan AM, Toth C. Percutaneous cystolithotomy for pediatric endemic bladder stone: experience with 155 cases from 2 developing countries. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:1628-1631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cassell III AK, Liberia; Pietroletti R, Italy S-Editor: Liu XF L-Editor: A P-Editor: Cai YX