Published online Apr 6, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i10.2267

Peer-review started: November 17, 2022

First decision: January 12, 2023

Revised: February 1, 2023

Accepted: March 6, 2023

Article in press: March 6, 2023

Published online: April 6, 2023

Processing time: 133 Days and 3 Hours

Primary seminoma of the prostate (PSP) is a rare type of extragonadal germ cell tumour that is easily misdiagnosed, owing to the lack of specific clinical features. It is therefore necessary for clinicians to work toward improving the accuracy of PSP diagnosis.

A 59-year-old male patient presenting with acute urinary retention was admitted to a local hospital. A misdiagnosis of benign prostatic hyperplasia led to an improper prostatectomy. Histopathology revealed PSP invading the bladder neck and bilateral seminal vesicles. Further radiotherapy treatment for the local lesion was performed, and the patient had a disease-free survival period of 96 mo. This case was analysed along with 13 other cases of PSP identified from the literature. Only four of the cases (28.6%) were initially confirmed by prostate biopsy. In these cases, imaging examinations showed an enlarged prostate (range 6-11 cm) involving the bladder neck (13/14). Of the 14 total cases, 11 (78.6%) presented typical pure seminoma cell features, staining strongly positive for placental alkaline phosphatase, CD117, and OCT4. The median age at diagnosis was 51 (range 27-59) years, and patients had a median progression-free survival time of 48 (range 6-156) mo after treatment by cisplatin-based chemotherapy combined with surgery or radiotherapy. The remaining three were cases of mixed embryonal tumours with focal seminoma, which had clinical features similar to those of pure PSP, in addition that they also had elevated serum alpha-fetoprotein, beta-human chorionic gonadotropin, and lactose dehydrogenase.

PSP should be considered in patients younger than 60 years with an enlarged prostate invading the bladder neck. Further prostate biopsies may aid in proper PSP diagnosis. Cisplatin-based chemotherapy is still the main primary therapy for PSP.

Core Tip: Primary seminoma of the prostate (PSP) is a rare type of extragonadal germ cell tumour that is easily misdiagnosed, owing to the lack of specific clinical features. To the best of our knowledge, there have been only 13 cases of PSP reported in the literature, and there is a lack of systemic research on the condition. Through this case report and literature review, we suggested that PSP should be considered in patients younger than 60 years with an enlarged prostate invading the bladder neck. This symptom occurs in 92.9% of PSP patients, and has a high sensitivity but low specificity for diagnosis. However, additional prostate biopsies may aid diagnosis, and histopathological studies are the most effective diagnostic technique. The prognoses of PSP patients are often good. While cisplatin-based chemotherapy remains to be the first-line treatment, surgery or radiotherapy may also be important options, depending on each patient’s response to chemotherapy and the location of the residual tumour.

- Citation: Cao ZL, Lian BJ, Chen WY, Fang XD, Jin HY, Zhang K, Qi XP. Diagnosis and treatment of primary seminoma of the prostate: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(10): 2267-2275

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i10/2267.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i10.2267

Germ cell tumours (GCTs) are growths of cells that form from reproductive cells. Most GCTs occur in the testicles or ovaries; however, some GCTs, named extragonadal germ cell tumours (EGCTs), occur in other areas of the body via mechanisms that remain unclear[1]. EGCTs are rare, and most of them occur in the midline of the body, such as mediastinal tumours, thymus tumours, retroperitoneal tumours, and pineal tumours[1]. Seminoma is the most common form of GCT, and one of the rare malignant tumours that can be cured by chemotherapy[2]. Primary seminoma of the prostate (PSP) without any primary testicular lesions is extremely rare. To the best of our knowledge, only 13 cases have been previously reported in the literature. The clinical symptoms of EGCTs are non-specific and vary according to tumour location. In the prostate, EGCTs may cause urinary symptoms. The clinical manifestations of PSP may include progressive dysuria, haematuria, and an enlarged prostate invading the bladder[3-7]. The diagnosis of PSP is difficult based on these non-specific clinical features alone, and the standard of treatment remains controversial[8-12]. We herein report the case of a patient with primary seminoma arising from the prostate. We also systematically review the previous literature on PSP and summarize potential optimal diagnostic and clinical management options for this tumor.

A 59-year-old man presenting with acute urinary retention was admitted to a local hospital in August 2014.

The patient had been diagnosed with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) for the preceding three years, with a chief symptom of progressive obstructive voiding.

The patient’s past medical history was unremarkable.

The patient denied any family history of related conditions.

Physical examination showed that the patient’s prostate was enlarged to more than twice the normal size, and was slightly hard without any palpable nodule on a digital rectal examination.

Microscopic haematuria was evident, but the patient’s serum prostate specific antigen (PSA) level was within normal limits (1.412 ng/mL).

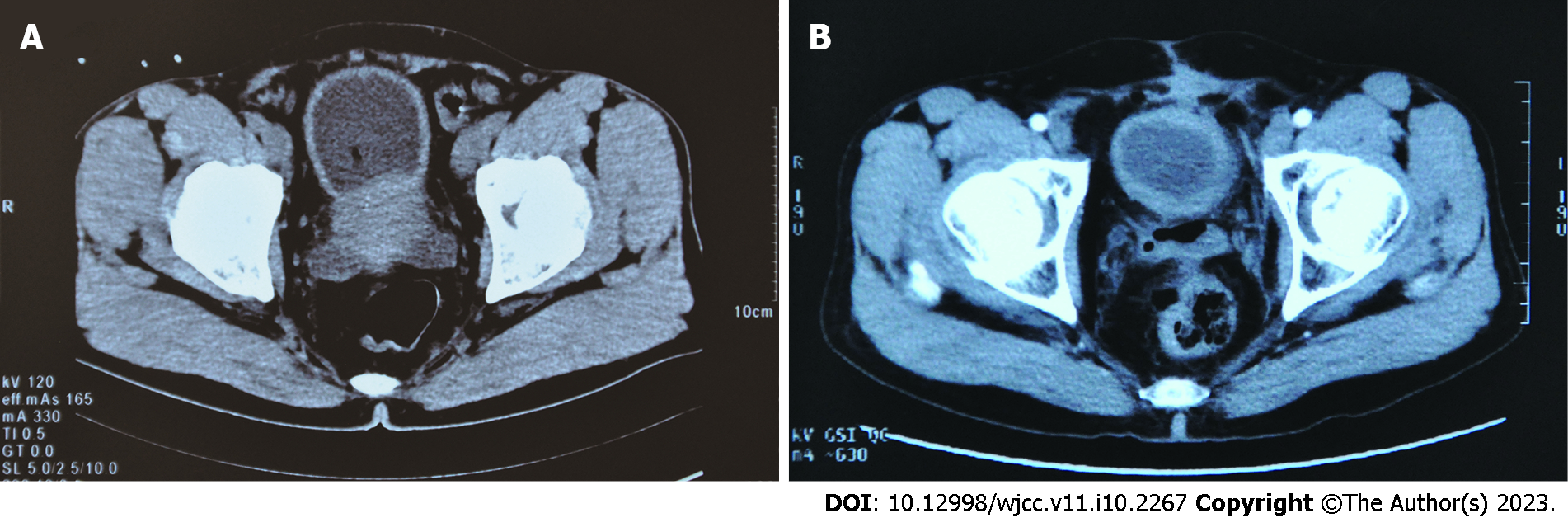

Ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) revealed an enlarged prostate (7.0 cm × 6.5 cm × 5.5 cm) involving the bladder neck (Figure 1A).

Due to the progression of the patient’s urinary symptoms despite medical treatment and lack of necessary equipment for transurethral resection of the prostate at the local hospital, the patient was initially submitted to traditional suprapubic prostatectomy. During the operation, it was confirmed that the lesion was more than just BPH, with a neoplasm that involved the prostate capsule, seminal vesicles, and bladder neck as well. Subsequently, the patient underwent prostatectomy, excision of the seminal vesicles, and rectal surgical repair (due to intraoperative rectal injury).

Histopathology revealed seminoma of the prostate, invading the bladder neck and bilateral seminal vesicles with a positive margin, but no involvement of the rectal wall. Postoperatively, careful examination of the scrotum, mediastinum, and retroperitoneum by ultrasound, and CT/magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanning revealed no neoplastic lesion. Serum GCT markers including alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG), and lactose dehydrogenase (LDH) had no abnormality.

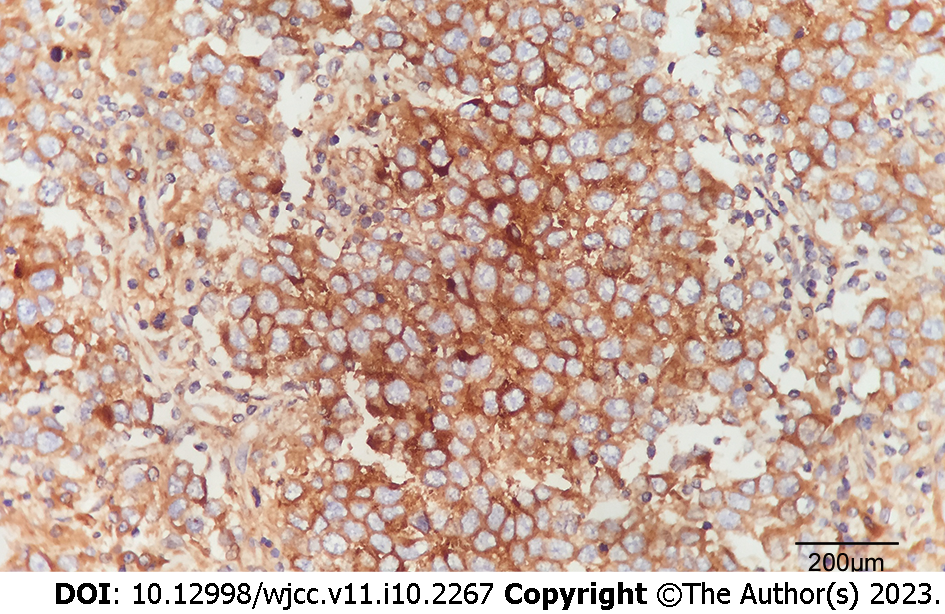

All prostatectomy specimens were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, and routinely processed. After referral to a tertiary hospital, histology sections were cut at 4 μm intervals and stained with haematoxylin and eosin. Immunohistochemical stains were prepared using the MaxVisionTM method (MaxVision TM HRP-Polymer anti-Mouse IHC Kit, Maixin Biotech. Co. Ltd, Fuzhou, China). Immunostains were performed for the following antibodies: AFP (polyclonal, Abnova, Taipei, Taiwan), β-hCG (clone ZSH17), pan-cytokeratin (clone AE1/AE3), high molecular weight cytokeratin (clone 34βE12), CD45RB/leukocyte common antigen (LCA) (clone PD7/26+2B11), vimentin (clone V9), S100 protein (clone 4c4.9), epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) (clone E29), Bcl-2 (clone 8C8), PSA (clone ER-PR8), prostatic serum acid phosphatase (PSAP) (clone PASE/4LJ), placental alkaline phosphatase (PLAP) (clone 8A9), CD117, and c-Kit (clone YR145) (β-hCG-CD117, c-Kit, all provided by Maixin Biotech. Co. Ltd., Fuzhou, China). Periodic acid-Schiff staining (ab-150680, Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) was also performed. Microscopically, the prostatectomy specimen revealed a poorly circumscribed infiltrative tumour with poorly-defined margins invading the prostate capsule, bladder neck, and bilateral seminal vesicles. The neoplastic cells were arranged in ill-defined solid nests, had no glandular structure, abundant clear cytoplasm, distinct cell membranes, and large hyperchromatic and prominent nucleoli. Many lymphocytes and plasma cells infiltrated into the interstitial tissue (Figure 2). Compared to common prostate adenocarcinomas, the atypical nests of the patient’s poorly-differentiated tumour cells were more prominent, with various abnormal areas of necrosis. Immunohistochemical studies demonstrated that the tumour cells were diffuse and showed strong expression of PLAP (Figure 3) and CD117 as well as positive periodic acid-Schiff staining, but were negative for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, 34βE12, PSA, PSAP, AFP, LCA, Bcl-2, vimentin, S100 protein, and EMA.

In addition, clustered data were also identified from other patients with seminoma involving the prostate through PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/) and ISI Web of Knowledge (http://apps.isiknowledge.com/) with a cutoff date of August 2022, using the terms seminoma and prostate (or “extragonadal”) (limitations “primary” and “English”). In addition to the current case, another 13 cases of PSP previously reported in the literature are summarized in Table 1 for comparative purposes. Of these, only four cases were initially confirmed by prostate biopsy (28.6%), and ten were initially misdiagnosed (71.4%) as carcinoma/tumour, sarcoma, BPH, or abscess. The common clinical manifestations were dysuria (10/14), haematuria (6/14), frequent urination (3/14), and lumbago (3/14). Imaging examinations showed an enlarged prostate (range 6-11 cm) involving the bladder neck (13/14, 92.8%). Of these, 11 (78.6%) presented with pure PSP, with a median age at diagnosis of 51 (range 27-59) years. Immunohistochemical examination showed that the typical seminoma cell components were all strongly positive for PLAP, CD117, OCT4, and negative for epithelial markers. All 11 patients had complete remission. Among the eight who received chemotherapy, three were treated just by chemotherapy, three by chemotherapy combined with surgery, and two with chemotherapy followed by further radiotherapy for the iliac lymph node. Of the remaining three, one received surgery and radiotherapy, one received just radiotherapy, and the third lacked detailed treatment information. The available follow-up for the 11 patients with pure PSP indicated a good prognosis with a median progression free survival of 48 (range 6-156) mo (Table 1). The remaining three all had mixed endodermal sinus tumours with focal seminoma of the prostate. Their ages at diagnosis were 24, 47, and 47 years, and their chief clinical findings were severe low urinary tract symptoms (dysuria, haematuria, and lumbago) and signs of prostatic enlargement, with elevated serum AFP, β-hCG, and LDH. Cisplatin-based chemotherapy was the main chemotherapy used for treatment. One patient died after 8 mo of chemotherapy, whereas the other two were still living after 16 and 12 mo, respectively.

| No. | Age | Symptoms | Finding (max size of the prostate) | Initial diagnosis | Treatment | Final diagnosis | Follow-up (mo) | Ref. |

| 1 | 51 | Lumbago, fatigue | Large prostate (6 cm) retroperitoneal mass | Adenocarcinoma | CBC 4 cycles | Prostate seminoma involving BN1 | 6 (alive) | Arai et al[3], 1988 |

| 2 | 58 | Hematuria, urgency | LPIBN (NA) | Bladder neck and prostate urethra tumor | CBC 3 cycles | Prostate seminoma involving BN2 | 10 (alive) | Khandekar et al[4], 1993 |

| 3 | 31 | Hematuria, dysuria, hematospermia | Large prostate (NA); lymph node mass (NA) | Prostate abscess | CBC 4 cycles + radiotherapy 40 Gy | Prostate seminoma involving BN, seminal vesicles2 | 156 (alive) | Hayman et al[5], 1995 |

| 4 | 27 | Hematuria, dysuria, lumbago | LPIBN (10 cm) | Rhabdomyosarcoma3 | Total pelvic exenteration + CBC 3 cycles | Prostate seminoma invading BN, seminal vesicles and rectal wall1 | 72 (alive) | Kimura et al[6], 1995 |

| 5 | 54 | Dysuria | LPIBN (NA) | Prostate seminoma3 | CBC 3 cycles | Prostate seminoma involving BN2 | 28 (alive) | Hashimoto et al[7], 2009 |

| 6 | 54 | Dysuria, nocturia | LPIBN (9.5 cm) | Prostate cancer3 | Total pelvic exenteration + CTX 9 cycles | Prostate seminoma invading BN, seminal vesicles1 | 132 (alive) | Zheng et al[8], 2015 |

| 7 | 47 | Dysuria, nocturia frequency, urgency | Large prostate (NA) | BPH | Transurethral resection of prostate + CBC 4 cycles | Prostate seminoma1 | 48 (alive) | Kazmi et al[9], 2019 |

| 8 | 46 | Dysuria, frequency | LPIBN (7.5 cm) | Prostate seminoma3 | CBC 2 cycles + radiotherapy 36 Gy | Prostate seminoma involving BN, seminal vesicles1 | NA | Gundavda et al[10], 2020 |

| 9 | 56 | Scrotal pain, frequency, urgency | LPIBN (10.2 cm) | Prostate seminoma3 | Radiotherapy 50 Gy | Prostate seminoma involving BN, seminal vesicles1 | 24 (alive) | Akingbade et al[11], 2021 |

| 10 | 35 | Dysuria | Large prostate mass (NA) | Prostate seminoma3 | NA | Prostate seminoma involving BN2 | NA | Hayasaka et al[12], 2011 |

| 11 | 59 | Hematuria, dysuria | LPIBN (7 cm) | BPH | Suprapubic prostatectomy + radiotherapy 36 Gy | Prostate seminoma invading BN and seminal vesicles1 | 96 (alive) | Current case |

| 124 | 24 | Microhematuria, lumbago | LPIBN (6 cm) | Prostatic tumor | Total prostatectomy + CBC 4 cycles | EST with seminoma in the prostate invading BN1 | 8 (dead) | Han et al[13], 2003 |

| 134 | 47 | Dysuria, hematuria | LPIBN (11 cm) | Adenocarcinoma3 | Radical prostatectomy + CBC 4 cycles | Immature teratoma, seminoma, EST invading BN1 | 16 (alive) | Liu et al[14], 2014 |

| 144 | 47 | Dysuria | LPIBN (11 cm) | BPH | Bleomycin, etoposide and cisplatin 4 cycles | Prostate with yolk sac tumor and seminoma invading BN1 | 12 (alive) | Antunes et al[15], 2018 |

A diagnosis of PSP was made, which satisfied the diagnostic criteria of the absence of any demonstrable tumour in either testis, and a tumour confined to the prostate and bladder neck, without regional lymph node/distant metastasis involvement.

Due to the positive margin and an apprehension over chemotherapy, image guided radiation therapy was performed with a total prostate regional dose of 36 Gy over 18 fractions in a regional hospital, 2 mo after the patient’s surgical operation.

Complete remission of the patient’s dysuria symptom was achieved, but frequency and urgency of urination persisted. In July 2015, the patient was referred to our hospital (a tertiary hospital). CT/MRI scanning showed no obvious mass at the surgical site (Figure 1B), and no evidence of para-aortic lymphadenopathy or distant metastasis. Cystoscopy showed a slightly coarse urothelium, especially at the posterior bladder neck and trigone. Histopathology by cystoscopy and biopsy revealed that the bladder neck had inflammatory reactants, but there was no evidence of tumour recurrence. The patient has been followed every 6 to 12 mo since that time, and has had a PSP disease-free survival for 96 mo so far, at the time of writing this report.

EGCTs are very rare but well-known neoplasms, arising principally from the mediastinum, retroperitoneum, thymus, or pineal gland, of which seminoma accounts for more than 60%[1]. Based on the current study, there have been a total of 14 cases of prostatic seminoma without testicular involvement, including 13 reported previously, of which 11 had primary pure seminoma and 3 had malignant embryonal tumour mixed with seminoma[13-15].

All PSPs in the patients had no specific symptoms, with progressive difficulty in urination being the most common symptom[4-8]. Seminoma grows slowly and manifests concealed, slow, progressive symptoms, so most tumours were bulky by the time when they were discovered, in late presentation. An enlarged prostate (range 6-11 cm) that is tender/slightly hard and extends into the bladder neck, may represent a significant clinical characteristic of PSP, especially for patients younger than 60 years. Of the 11 cases of pure seminoma, the median age at diagnosis was 51 (range 27-59) years, whereas patients with mediastinal or retroperitoneal primary seminoma were diagnosed at a median age of 33 (range 18-65) or 41 (range 23-70) years, respectively[16]. An initial misdiagnosis of PSP occurred in 71.4% of patients. This study highlights the notion that a prostate biopsy is crucial for an accurate diagnosis and proper management strategy for PSP, with positive immunohistochemical staining for PLAP, OCT4, and CD117, or negative biochemical tests such as PSA, AFP, β-hCG, and LDH, similar to the case for testicular seminoma[16-18]. In the case that we described, a lack of prostate biopsy before prostatectomy in the local hospital was a significant shortcoming. Operative morbidity including rectal injury could have been avoided if a biopsy had been done, considering the patient’s CT findings.

Cytogenetically, most EGCTs are similar to their testicular counterparts[18]. The diagnosis of primary extragonadal seminoma requires careful examination of the entire body, particularly in males, and the condition should be considered as being primary in that area until the testes have been thoroughly examined and excluded as a possible source[18]. It has been documented that metastases from occult testicular tumours may masquerade as primary EGCTs if the original tumour site has already regressed, leaving only a scar, referred to in the literature as a “burned-out” primary[13,16,19-21]. Approximately 1/3 of patients with EGCTs present with metachronous testicular carcinoma in situ[22]. As in the current case, examination data often suggest normal testes, which implies that testicular biopsies should not be recommended[23]. Clinical gonadal ultrasound examination and biochemical marker (AFP, β-hCG, and LDH) tests should be routinely performed, however, and urinary cytology examination should be considered[20-24].

Seminomas have been noted to be sensitive to both chemotherapy and radiotherapy. The relapse-free rates in patients with stage 1 testicular seminoma managed with surveillance, radiotherapy, 1 × carboplatin, and 2 × carboplatin were 91.8%, 97.6%, 95%, and 98.5%, respectively, after a 30-mo follow-up, in one report[25]. Based on current data, the optimal treatment for PSP remains controversial due to the limited number of cases. All 11 of the pure PSP cases that we described here, including our case, achieved complete remission after treatment, with a specific progression free survival rate of 100%. Two other cases with iliac lymph node metastases had a specific progression free survival rate of over 10 years. Of these two cases, one received cisplatin-based chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy[5], while the other received nine cycles of cyclophosphamide after total pelvic exenteration[8]. Three other cases received only cisplatin-based chemotherapy and had no relapses[3,4,7]. These results suggest that cisplatin-based chemotherapy as a primary therapy for PSP has a good curative effect, consistent with the efficacy of primary chemotherapy for patients with extragonadal seminoma (an objective remission rate of 92% and a 5-year overall survival rate of 88%). Chemotherapy should therefore be considered as the first-line therapy for these cases. In this case, radiotherapy was performed after prostatectomy, which found no evidence of distant metastasis and a positive tumour margin. This course of therapy resulted in a complete remission lasting over 6 years. Another case with a suspicious iliac lymph node was also treated with radiotherapy alone, and achieved complete remission for at least 2 years[11]. However, it should be noted that recurrence rates approach 50% in patients with mediastinal or bulky retroperitoneal seminoma who are treated only by radiotherapy[16,24]. Because there are few cases reported of patients treated only by radiotherapy, the use of radiotherapy alone in patients with PSP should be considered carefully, and the most appropriate option still seems to be chemotherapy for cases of PSP with extraprostatic invasion[16,24].

Regarding the issue of Klinefelter syndrome (KS), there are more than 50 cases of KS in patients with EGCTs of the nonseminomatous subtype reported[26-30]. In the present study, one-tenth of the cases with prostate pure seminoma also presented with KS. Bokemeyer et al[16,24] reported that all 103 patients who presented with extragonadal seminomas in their study (51 mediastinal and 52 retroperitoneal seminomas), however, had no KS[31-33]. Further studies are needed to clarify the role of KS in this rare tumour type.

The clinical presence of an enlarged prostate invading the bladder neck, and laboratory examination of prostate biopsies, may help in the diagnosis of the extremely rare pure PSP form of cancer. Cisplatin-based chemotherapy seems to be the first-line treatment for this condition, and surgery or radiotherapy may also represent important treatment options, depending on each patient’s response to chemotherapy and the location of the residual tumour.

| 1. | Mahankali P, Trimble L, Panciera D, Li H, Obaid T. Extragonadal Perirectal Mature Cystic Teratoma in the Adult Male. CRSLS. 2022;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lian B, Zhang W, Wang T, Yang Q, Jia Z, Chen H, Wang L, Xu J, Wang W, Cao K, Gao X, Sun Y, Shao C, Liu Z, Li J. Clinical Benefit of Sorafenib Combined with Paclitaxel and Carboplatin to a Patient with Metastatic Chemotherapy-Refractory Testicular Tumors. Oncologist. 2019;24:e1437-e1442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Arai Y, Watanabe J, Kounami T, Tomoyoshi T. Retroperitoneal seminoma with simultaneous occurrence in the prostate. J Urol. 1988;139:382-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Khandekar JD, Holland JM, Rochester D, Christ ML. Extragonadal seminoma involving urinary bladder and arising in the prostate. Cancer. 1993;71:3972-3974. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Hayman R, Patel A, Fisher C, Hendry WF. Primary seminoma of the prostate. Br J Urol. 1995;76:273-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kimura F, Watanabe S, Shimizu S, Nakajima F, Hayakawa M, Nakamura H. [Primary seminoma of the prostate and embryonal cell carcinoma of the left testis in one patient: a case report]. Nihon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi. 1995;86:1497-1500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hashimoto T, Ohori M, Sakamoto N, Matsubayashi J, Izumi M, Tachibana M. Primary seminoma of the prostate. Int J Urol. 2009;16:967-970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zheng W, Wang L, Yang D, Fang K, Chen X, Wang X, Li X, Li Z, Song X, Wang J. Primary extragonadal germ cell tumor: A case report on prostate seminoma. Oncol Lett. 2015;10:2323-2326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kazmi Z, Sulaiman N, Shaukat M, Rafi A, Ahmed Z, Ather MH. Atypical Presentation of Seminoma in the Prostate - Case Report. Urology. 2019;132:33-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gundavda K, Bakshi G, Prakash G, Menon S, Pal M. The Curious Case of Primary Prostatic Seminoma. Urology. 2020;144:e6-e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Akingbade A, Gopaul D, Brastianos HC, Hubay S. Radiotherapy as a Single Modality in Primary Seminoma of the Prostate. Cureus. 2021;13:e14264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hayasaka K, Koyama M, Fukui I. FDG PET imaging in a patient with primary seminoma of the prostate. Clin Nucl Med. 2011;36:593-594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Han G, Miura K, Takayama T, Tsutsui Y. Primary prostatic endodermal sinus tumor (yolk sac tumor) combined with a small focal seminoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:554-559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Liu SG, Lei B, Li XN, Chen XD, Wang S, Zheng L, Zhu HL, Lin PX, Shen H. Mixed extragonadal germ cell tumor arising from the prostate: a rare combination. Asian J Androl. 2014;16:645-646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Antunes HP, Almeida R, Sousa V, Figueiredo A. Mixed extragonadal germ cell tumour of the prostate. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bokemeyer C, Nichols CR, Droz JP, Schmoll HJ, Horwich A, Gerl A, Fossa SD, Beyer J, Pont J, Kanz L, Einhorn L, Hartmann JT. Extragonadal germ cell tumors of the mediastinum and retroperitoneum: results from an international analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1864-1873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 323] [Cited by in RCA: 315] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Alsharif M, Aslan DL, Jessurun J, Gulbahce HE, Pambuccian SE. Cytologic diagnosis of metastatic seminoma to the prostate and urinary bladder: a case report. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36:734-738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gîngu CV, Mihai M, Baston C, Crăsneanu MA, Dick AV, Olaru V, Sinescu I. Primary retroperitoneal seminoma - embryology, histopathology and treatment particularities. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2016;57:1045-1050. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Plummer ER, Greene DR, Roberts JT. Seminoma metastatic to the prostate resulting in a rectovesical fistula. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2000;12:229-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Farnham SB, Mason SE, Smith JA Jr. Metastatic testicular seminoma to the prostate. Urology. 2005;66:195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Torelli T, Lughezzani G, Catanzaro M, Nicolai N, Colecchia M, Biasoni D, Piva L, Maffezzini M, Stagni S, Necchi A, Giannatempo P, Farè E, Salvioni R. Prostatic metastases from testicular nonseminomatous germ cell cancer: two case reports and a review of the literature. Tumori. 2013;99:e203-e207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Fosså SD, Aass N, Heilo A, Daugaard G, E Skakkebaek N, Stenwig AE, Nesland JM, Looijenga LH, Oosterhuis JW. Testicular carcinoma in situ in patients with extragonadal germ-cell tumours: the clinical role of pretreatment biopsy. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:1412-1418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Comiter CV, Renshaw AA, Benson CB, Loughlin KR. Burned-out primary testicular cancer: sonographic and pathological characteristics. J Urol. 1996;156:85-88. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Bokemeyer C, Droz JP, Horwich A, Gerl A, Fossa SD, Beyer J, Pont J, Schmoll HJ, Kanz L, Einhorn L, Nichols CR, Hartmann JT. Extragonadal seminoma: an international multicenter analysis of prognostic factors and long term treatment outcome. Cancer. 2001;91:1394-1401. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Chung P, Daugaard G, Tyldesley S, Atenafu EG, Panzarella T, Kollmannsberger C, Warde P. Evaluation of a prognostic model for risk of relapse in stage I seminoma surveillance. Cancer Med. 2015;4:155-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Nichols CR, Heerema NA, Palmer C, Loehrer PJ Sr, Williams SD, Einhorn LH. Klinefelter's syndrome associated with mediastinal germ cell neoplasms. J Clin Oncol. 1987;5:1290-1294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Tay HP, Bidair M, Shabaik A, Gilbaugh JH 3rd, Schmidt JD. Primary yolk sac tumor of the prostate in a patient with Klinefelter's syndrome. J Urol. 1995;153:1066-1069. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Namiki K, Tsuchiya A, Noda K, Oyama H, Ishibashi K, Kusama H, Furusato M. Extragonadal germ cell tumor of the prostate associated with Klinefelter's syndrome. Int J Urol. 1999;6:158-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Aguirre D, Nieto K, Lazos M, Peña YR, Palma I, Kofman-Alfaro S, Queipo G. Extragonadal germ cell tumors are often associated with Klinefelter syndrome. Hum Pathol. 2006;37:477-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Konheim JA, Israel JA, Delacroix SE. Klinefelter Syndrome with Poor Risk Extragonadal Germ Cell Tumor. Urol Case Rep. 2017;10:1-3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Shi D, Chen C, Huang H, Tian J, Zhou J, Jin S. Primary seminoma of prostate in a patient with Klinefelter syndrome: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e29117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 32. | Inai H, Kawai K, Morishita Y, Nagata M, Noguchi M, Akaza H. Retroperitoneal extragonadal germ cell tumor in a patient with Klinefelter's syndrome. Int J Urol. 2005;12:765-767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kurabayashi A, Furihata M, Matsumoto M, Sonobe H, Ohtsuki Y, Aki M, Kuwahara M. Primary intrapelvic seminoma in Klinefelter's syndrome. Pathol Int. 2001;51:624-628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Boopathy Vijayaraghavan KM, India; Faraji N, Iran; Marickar F, India S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Fan JR