Published online Mar 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i7.2275

Peer-review started: July 21, 2021

First decision: September 1, 2021

Revised: September 25, 2021

Accepted: January 25, 2022

Article in press: January 25, 2022

Published online: March 6, 2022

Processing time: 223 Days and 18.8 Hours

Dandy-Walker malformation (DWM) was first reported in 1914. In this case report, a pediatric case was complicated with giant and isolated arachnoid cysts in the right cerebellar hemisphere along with the typical DWM.

The patient was at 20 mo old boy, with the complaint of staggering for more than 2 mo. He was admitted to the hospital due to high intracranial pressure and staggering. At admission, the patient had typical manifestations of high intracranial pressure, including vomiting, poor appetite and feeding difficulty. Physical examination revealed increased head circumference, closed anterior fontanelle, unstable standing, staggering, leaning right while walking and ataxia. After admission, he was diagnosed with DWM accompanied by giant isolated arachnoid cysts in the posterior fossa. He underwent Y-shaped three-way valve repair for treating differential pressure between the supratentorial hydrocephalus and the subtentorial arachnoid cysts at once. The child recovered well after the surgery.

In this case, supratentorial and subtentorial shunts were placed, which solved the problem of differential pressure between the supratentorial and subtentorial parts simultaneously. This provides useful information regarding treatment exploration in this rare disease.

Core Tip: Dandy-Walker malformation (DWM) is a rare congenital malformation characterized by partial or complete dysplasia of the cerebellar vermis, cystic dilation of the four ventricles, upward displacement of the tentorium, increased anteroposterior diameter of the posterior fossa, and connection between the posterior fossa cysts with the four ventricles in most cases. DWM with giant isolated arachnoid cysts in the posterior fossa was treated with a combination of supratentorial and subtentorial cyst shunts safely and effectively.

- Citation: Dong ZQ, Jia YF, Gao ZS, Li Q, Niu L, Yang Q, Pan YW, Li Q. Y-shaped shunt for the treatment of Dandy-Walker malformation combined with giant arachnoid cysts: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(7): 2275-2280

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i7/2275.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i7.2275

Dandy-Walker malformation (DWM) was first reported by Dandy and Blackfan[1] in 1914. It is a rare congenital malformation characterized by partial or complete dysplasia of the cerebellar vermis, cystic dilation of the four ventricles, upward displacement of the tentorium, increased anteroposterior diameter of the posterior fossa, and connection between the posterior fossa cysts with the four ventricles in most cases[2]. According to the latest epidemiological survey in Europe, the incidence rates of DWM are 6.79/100000 and 2.74/100000 in infants and live births, respectively[3]. The diagnosis of DWM mainly relies on imaging. The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) manifestations of DWM are: (1) Presence of giant arachnoid cysts in the posterior fossa that communicate with the fourth ventricle, with elevated tentorium cerebelli and torcular herophili due to pressure; (2) Developmental abnormality or deficiency of cerebellar vermis, which might be accompanied by cerebellar hemisphere dysplasia and forward displacement of the brain stem due to pressure; (3) Significant dilation of the three ventricles and the lateral ventricles, as well as hypoplasia of the corpus callosum; and (4) Hydrocephalus in about 70%-90% of patients[4]. Differential diagnosis included: (1) Giant arachnoid cysts in the posterior fossa, which manifest as cysts of cerebrospinal fluid density, but are not connected with the fourth ventricle. The cysts might be separated by trabeculae, and the fourth ventricle remained normal. The cerebellar vermis appeared normal, but was shifted; and (2) Enlarged cisterna magna, in which cysts are present in different sizes, normally ranging from 2-6 cm. The cerebellar vermis, cerebellar hemisphere and the fourth ventricle appeared normal, with no occupying effect, no hydrocephalus, and normal size of the posterior fossa. In this case report, typical characteristics of DWM were found, and were accompanied by giant and isolated arachnoid cysts in the posterior fossa, warranting different preoperative evaluation and intraoperative treatment.

Family members complained that the child could not walk steadily for 2 mo.

The family members reported that the child was admitted to a local hospital due to fever, diarrhea and vomiting 2 mo ago, and was diagnosed with a cold. He was administered intramuscular injections of antibiotics for 5 d (specific drugs unknown), and showed improvement in his condition. However, staggering occurred again, and the boy was unable to sit or stand. The family members brought him to our hospital for further care, and the patient was admitted in the inpatient department of our Pediatric Neurology Department.

Physical examination at the time of admission revealed increased head circumference (52 cm), closed anterior fontanelle, unstable standing, staggering, and ataxic gait.

Blood routine examination showed that leukocyte elevation. Urine routine, fecal routine and occult blood examination, blood biochemistry, immune indexes and infection indexes were normal.

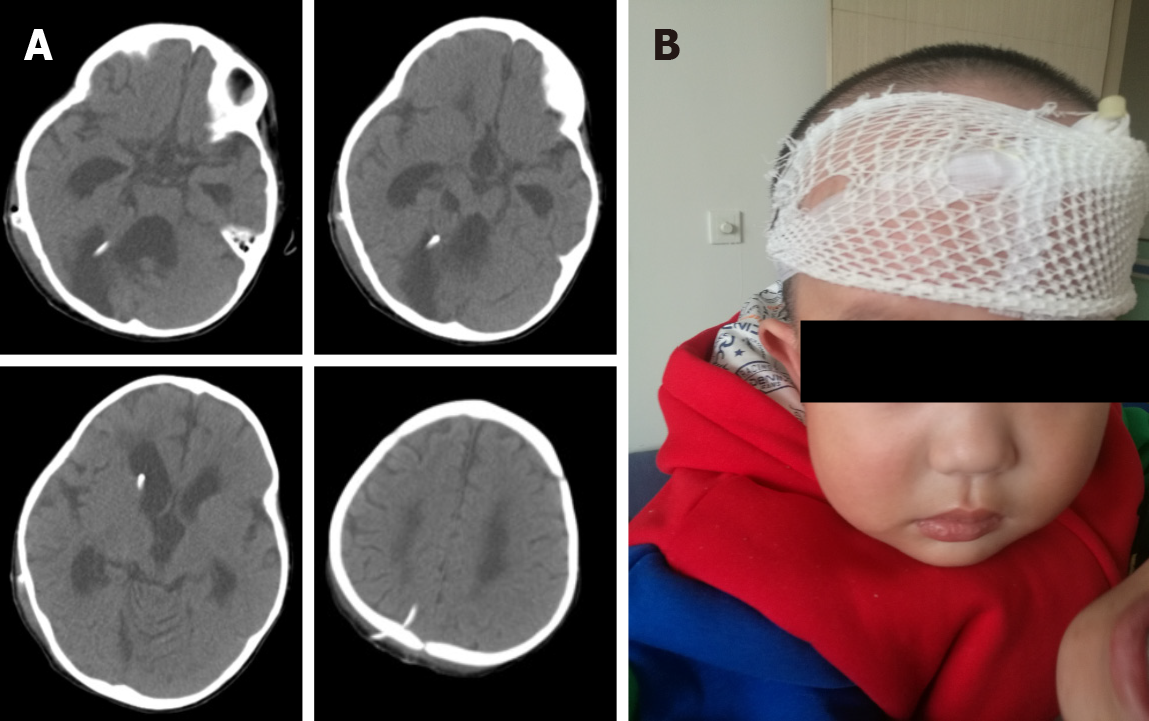

Brain computed tomography (CT) and MRI revealed significantly dilated supratentorial ventricles, capped edema at bilateral frontal angles, huge occupying cysts in the right cerebellar hemisphere, and compression displacement in the right cerebellar hemisphere and the four ventricles (Figure 1).

The patient was a 20 mo old boy, initial diagnosis revealed DWM with giant isolated arachnoid cysts in the posterior fossa. After admission, the patient underwent stereotaxic aspiration for arachnoid cysts in the posterior fossa, confirming that the cystic fluid was cerebrospinal fluid and excluding malignant lesions. After stereotaxic aspiration, the cysts were significantly shrunk, but the supratentorial hydrocephalus showed no improvement. It was speculated that aqueduct obstruction due to adhesion rather than compression would result in occlusion between the supratentorial and subtentorial parts; meanwhile, unobstructed aqueduct and blocked fourth ventricle outlet would result in obstructive hydrocephalus between the supratentorial and subarachnoid spaces. Neither a cysto-peritoneal shunt (C-P shunt) nor a ventriculoperitoneal shunt (V-P shunt) alone solved the hydrocephalus at the same time, and the patient underwent a combination of supratentorial-infratentorial shunt placement for the hydrocephalus and isolated cysts. Preoperative cystic fluid analysis confirmed that the cystic fluid was clear, and the typical arachnoid cysts included proteins at 0.32 (reference: 0.24-0.44 g/L), glucose at 2.9 (reference: 2.4-4.4 mmol/L), and chlorine at 116.1 (reference: 119.0-129.0 mmol/L). They were colorless and transparent, with negative Pandy’s test and white blood cell at 4.0 (reference: 0.00-8.00 × 106/L).

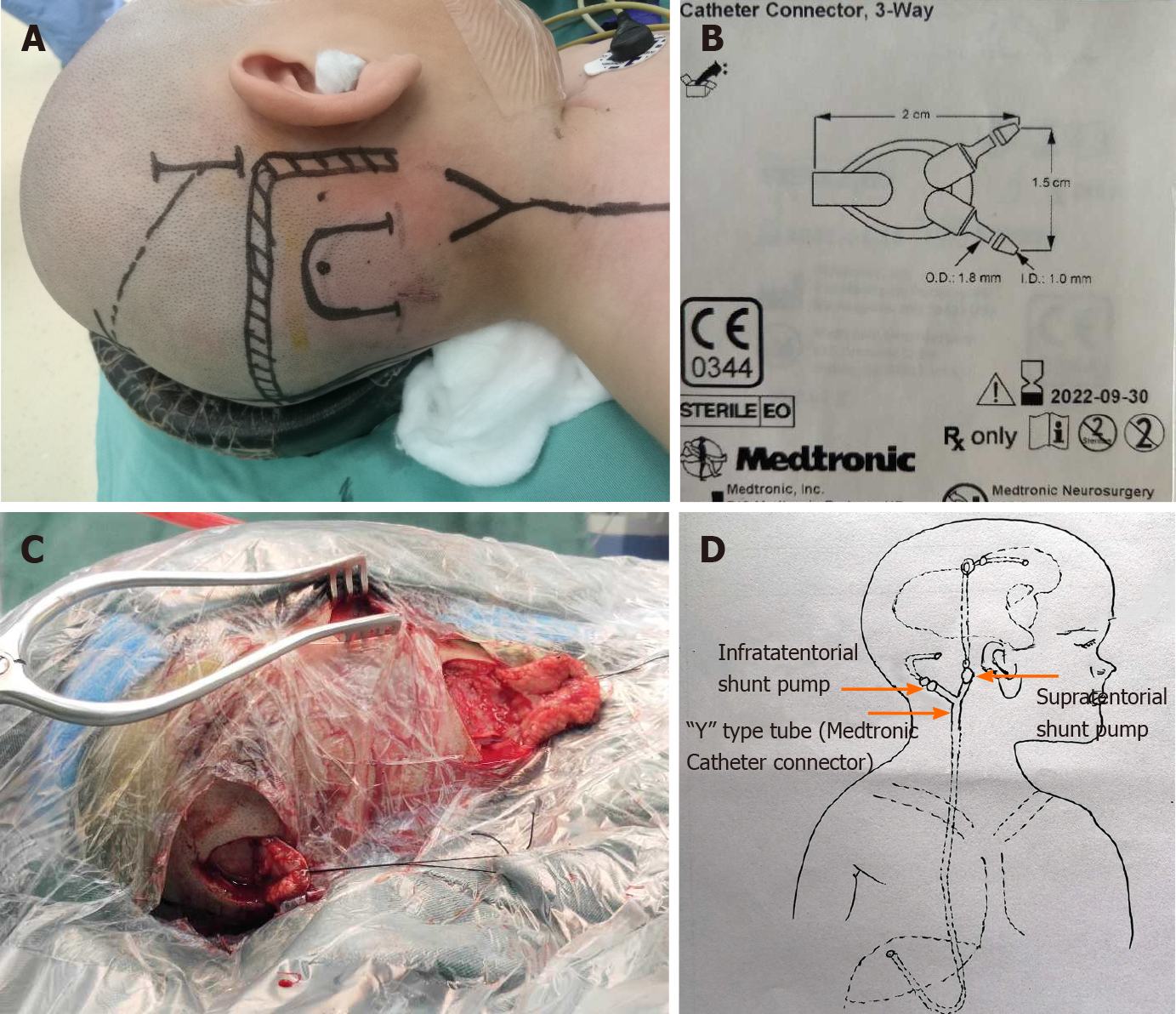

For the surgical procedure, the occipital puncture point was located 5 cm above the external occipital protuberance and 2.5 cm lateral to the midline. A U-shaped incision was made on the scalp (Figure 2A and C). Then, a bone hole of 3-mm diameter was made using a bone drill, which was 10 cm in depth and directed 2 cm above the midpoint of the ipsilateral superciliary arch. Afterwards, a longitudinal incision was made at the posterosuperior part of the ear, and a supratentorial adjustable pump (Medtronic, Strata® II Shunt Assembly, Regular, with BioGlide®; pressure, 80 cmH2O) was placed behind the ear, connected to a three-way valve (Medtronic Catheter Connector, 3-Way) (Figure 2D). A subtentorial puncture was performed at 5 cm lateral to the midline and 2 cm below the transverse sinus. A U-shaped incision was made on the scalp (Figure 2A and C), and a 3-mm diameter bone hole was made using a bone drill, which was 3 cm in depth and directed to the vertical bone plate. A drainage tube was connected to the ordinary non-adjustable pump (Medtronic, Delta® shunt Kit, Regular, Performance Level 1.5), and further connected to the three-way valve. The other end of the three-way valve was connected to the end of the abdominal cavity, as in general shunt therapy (Figure 2B).

After the surgery, the child had no significant complications, and showed improvement with regarding to the symptoms of staggering and high intracranial pressure. On the third day after operation, he could walk independently. Postoperative CT showed significant improvement of supratentorial hydrocephalus and shrunk cysts in the posterior fossa, and the compressed cerebellar hemisphere was restored (Figure 3A). In addition, the incision healed well postoperatively, and the child’s mental state was improved significantly (Figure 3B). The child was depressed before operation.

Initial diagnosis revealed DWM with giant isolated arachnoid cysts in the posterior fossa.

The patient underwent a combined shunt for supratentorial hydrocephalus and infratentorial giant solitary arachnoid cysts.

The patient had no complications, such as fever, subdural effusion and hematoma after operation, and recovered well. The patient was followed-up for 2 years, and could walk independently; high intracranial pressure had disappeared and he was feeding normally.

About 20% of patients with DWM had no clinical symptoms and require no treatment. Experts around the world continue to debate regarding the treatment of patients with DWM and hydrocephalus. Mohanty et al[5] retrospectively analyzed the surgical methods utilized in 72 children with DWM. The initial surgical treatments included V-P shunt placement in 21 patients, C-P shunt placement in 24, and combined V-P and C-P shunt insertion in 3. Twenty-one patients underwent endoscopic procedures and 3 cases underwent membrane excision via a posterior fossa craniectomy. The authors believed that neuroendoscopy is a good surgical method for DWM. Mohanty et al[5] pointed out hernia above posterior fossa cysts as a potential complication of V-P shunting alone, which rapidly deteriorates the clinical symptoms. In addition, C-P shunting alone is associated with a risk of chronic inferior herniation of the cerebral hemisphere through tentorial notch or causes tethering of the brain stem[6-8]. Kumar et al[9] compared different treatment methods and outcomes in 42 patients, and proposed V-P shunting should be followed by C-P shunting as posterior fossa cysts did not disappear or the symptoms recurred after V-P shunt placement. Meanwhile, if C-P shunting alone is implemented, this should be followed by V-P shunt placement as well due to continuous dilation of lateral ventricles. Hence, lateral ventricle and cyst shunting was performed to decompress the posterior fossa cysts and lateral ventricle simultaneously, thereby achieving the purpose of clinical cure. Generally, cyst fenestration is suitable for patients without hydrocephalus.

The child in the current case report suffered from cerebellar vermis dysphasia, accompanied by giant isolated arachnoid cysts in the posterior fossa, with the arachnoid cysts not connected to the occipital cistern. The supratentorial ventricle was enlarged, and there was an obvious capped edema at the bilateral frontal angle. Regardless of aqueduct obstruction status, the supratentorial or ventriculoperitoneal shunt alone did not solve the problem of arachnoid cysts that compressed the cerebellum as well as the brain stem. After sufficient preoperative evaluation, the patient received a ventriculoperitoneal shunt (adjustable anti-siphonic diverter pump) combined with a arachnoid cyst (medium pressure non-adjustable diverter pump)-peritoneal shunt, during which the Y-shaped three-way valve was finally used to simultaneously solve the problem of different pressures between the supratentorial hydrocephalus and the subtentorial arachnoid cyst induced by Dandy-Walker malformation. The patient had no complications, such as fever, subdural effusion and hematoma after operation, and recovered well. Therefore, the abovementioned procedure has a positive effect on the prognosis of patient. The patient was followed-up for 2 years, and could walk independently; the high intracranial pressure had disappeared, and the boy was feeding normally. Nonetheless, the efficacy of the surgery is subjected to long-term follow-up. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report of DWM with giant isolated arachnoid cysts in the posterior fossa, which was treated with a combination of supratentorial and subtentorial cyst shunts.

| 1. | Dandy WE, Blackfan KD. Internal hydrocephalus: an experimental, clinical and pathological study. Am J Dis Child. 1914;8:406-482. |

| 2. | Karande V, Andrade NN. Dandy-Walker Syndrome with Giant Cell Lesions and Cherubism. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2018;8:131-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Santoro M, Coi A, Barišić I, Garne E, Addor MC, Bergman JEH, Bianchi F, Boban L, Braz P, Cavero-Carbonell C, Gatt M, Haeusler M, Kinsner-Ovaskainen A, Klungsøyr K, Kurinczuk JJ, Lelong N, Luyt K, Materna-Kiryluk A, Mokoroa O, Mullaney C, Nelen V, Neville AJ, O'Mahony MT, Perthus I, Randrianaivo H, Rankin J, Rissmann A, Rouget F, Schaub B, Tucker D, Wellesley D, Yevtushok L, Pierini A. Epidemiology of Dandy-Walker Malformation in Europe: A EUROCAT Population-Based Registry Study. Neuroepidemiology. 2019;53:169-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Reith W, Haussmann A. [Dandy-Walker malformation]. Radiologe. 2018;58:629-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mohanty A, Biswas A, Satish S, Praharaj SS, Sastry KV. Treatment options for Dandy-Walker malformation. J Neurosurg. 2006;105:348-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wang AN, Carson BS. Upward herniation of the posterior fossa cyst in the shunted child. Surg Neurol. 1987;28:215-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Naidich TP, Radkowski MA, McLone DG, Leestma J. Chronic cerebral herniation in shunted Dandy-Walker malformation. Radiology. 1986;158:431-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Liu JC, Ciacci JD, George TM. Brainstem tethering in Dandy-Walker syndrome: a complication of cystoperitoneal shunting. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:1072-1074. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kumar R, Jain MK, Chhabra DK. Dandy-Walker syndrome: different modalities of treatment and outcome in 42 cases. Childs Nerv Syst. 2001;17:348-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Clinical neurology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Dhali A, Elpek GO, Naswhan AJ, Teragawa H S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yan JP