Published online Feb 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i4.1447

Peer-review started: October 6, 2021

First decision: October 27, 2021

Revised: November 7, 2021

Accepted: December 25, 2021

Article in press: December 25, 2021

Published online: February 6, 2022

Processing time: 109 Days and 17.4 Hours

Bleeding from gastroesophageal varices (GOV) is a serious complication in patients with liver cirrhosis, carrying a very high mortality rate. For secondary prophylaxis against initial and recurrent bleeding, endoscopic therapy is a critical intervention. Endoscopic variceal clipping for secondary prophylaxis in adult GOV has not been reported.

A 66-year-old man with cirrhosis was admitted to our hospital complaining of asthenia and hematochezia for 1 wk. His hemoglobin level and red blood cell counts were significantly decreased, and his fecal occult blood test was positive. An enhanced computed tomography of the abdomen showed GOV. The patient was diagnosed with hepatitis B cirrhosis-related GOV bleeding. A series of palliative treatments were administered, resulting in significant clinical impro

Our results suggest that endoscopic clipping is an inexpensive, safe, easy, effective, and tolerable method for the secondary prophylaxis of bleeding from gastric type 2 GOV. However, additional research is indicated to confirm its long-term safety and efficacy.

Core Tip: Gastrointestinal bleeding as a sequela of portal hypertension can be catastrophic and fatal. For patients without secondary prevention, the rebleeding and mortality rate is high; therefore, secondary prophylaxis is vital, and endoscopic techniques are primary methods used to perform this. Our novel endoscopic technique could play a critical role in the prevention of variceal re-bleeding, and we propose that it is a safe and efficacious method for the secondary prophylaxis of Type 2 GOV rebleeding. Our work provides an idea for the further study in this field.

- Citation: Yang GC, Mo YX, Zhang WH, Zhou LB, Huang XM, Cao LM. Endoscopic clipping for the secondary prophylaxis of bleeding gastric varices in a patient with cirrhosis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(4): 1447-1453

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i4/1447.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i4.1447

One of the most life-threatening complications of liver cirrhosis is acute variceal bleeding, which is associated with an increased mortality rate of approximately 20% at 6 wk[1]. For patients without secondary prevention, the rebleeding rate was as high as 60%, and the mortality rate reached 33% within 1-2 years[2]. Therefore, secondary prophylaxis is vital, and endoscopy is the primary method used to perform secondary prophylaxis techniques. A variety of techniques, including endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL), endoscopic injection sclerosis (EIS), and tissue adhesive injection, are available to manage gastroesophageal varices (GOV). GOV can be divided into Type 1 GOV and Type 2 GOV (GOV 2). GOV1 manifests as relatively straight varices extending along the lesser curvature of stomach to 2-5 cm below the gastroesophageal junction, while GOV 2 extends beyond the gastroesophageal junction into the fundus of the stomach[3]. However, these treatments are not without potentially serious complications. EVL, which can cause cerebral air embolism[4] and infective endocarditis[5], has not been widely used in gastric varices. EIS has a high complication rate for gastric ulceration, perforation, and rebleeding (37%-53%)[3,6], and its sclerosing agent can leak into the inferior vena cava[7]. The tissue adhesive injection procedure can result in embolization, leading to potentially fatal complications such as pulmonary[8] and spinal cord embolisms[9]. Endoscopic hemostatic metal clips were first designed by Hayashi et al[10] in 1975 and were initially used to achieve hemostasis in focal gastrointestinal bleeding[11] with the added benefit of a low rebleeding rate[12]. To our knowledge, endoscopic variceal clipping (EVC) for secondary prophylaxis in adult GOV has not been reported. Therefore, we present a retrospective case in which metal clips were utilized for the treatment of severe GOV 2 in a cirrhotic patient and evaluate the efficacy of EVC.

A 66-year-old man with cirrhosis was admitted to our hospital with a complaint of asthenia and hematochezia for 1 wk.

The patient had black stool for 1 wk and frequent bouts of asthenia.

He had a significant medical history of diabetes, hypersplenism, hypoalbuminemia, cholecystitis, mild anemia and bradycardia, and hepatitis B/decompensated cirrhosis, for which he received entecavir.

He had no history of alcohol abuse, toxic exposure, or hereditary disease.

His vitals at admission and pertinent physical examination findings were notable for a pulse of 84 and blood pressure 134/76 mmHg; he was lucid with a hepatic face, pale lips and conjunctiva, palmar erythema, chest spider angiomas, and mild bilateral pitting edema; the rest of his examination findings were unremarkable.

Initial laboratory test results were shown in Table 1. The 14C-urea breath test was negative.

| Result | Reference range | ||

| Red blood cell count, × 1012/L | 1.89 | 3.8-5.8 | Decreased |

| Hemoglobin level, g/dL | 59 | 115-175 | Decreased |

| Alkaline phosphatase, U/L | 43 | 45-125 | Decreased |

| Albumin, g/L | 29.4 | 40-55 | Decreased |

| Total protein, g/L | 56.1 | 65-85 | Decreased |

| Alanine aminotransferase, U/L | 16 | 9-50 | Normal |

| Serum creatinine, μmol/L | 75 | 57-111 | Normal |

| Direct bilirubin, μmol/L | 7.9 | 0-6.89 | Increased |

| Plasma fibrinogen level, g/L | 4.44 | 2-4 | Increased |

| Random blood glucose, mmol/L | 29.45 | 3.89-6.11 | Increased |

| Plasma D-dimer, mg/L | 0.61 | 0-0.5 | Increased |

| Urea nitrogen, mmol/L | 9.76 | 3.6-9.5 | Increased |

| Serum lipase, U/L | 133.9 | 13-60 | Increased |

| Creatine kinase, U/L | 382 | 50-310 | Increased |

| Alpha-fetoprotein, ng/mL | 17.4 | 0-13.6 | Increased |

| Glycosylated hemoglobin, % | 7.6 | 4.0-6.5 | Increased |

| Hepatitis B virus DNA, iu/mL | 9020 | < 100 | Increased |

| Hepatitis B virus surface antigen | Positive | Negative | Abnormal |

| Hepatitis B E antibody | Positive | Negative | Abnormal |

| Hepatitis B core antibody | Positive | Negative | Abnormal |

| Fecal occult blood test | Positive | Negative | Abnormal |

| Hepatitis C virus antibody | Negative | Negative | Normal |

| Helicobacter pylori antibody | Negative | Negative | Normal |

| Human immunodeficiency virus antibody | Negative | Negative | Normal |

| Syphilis antibody | Negative | Negative | Normal |

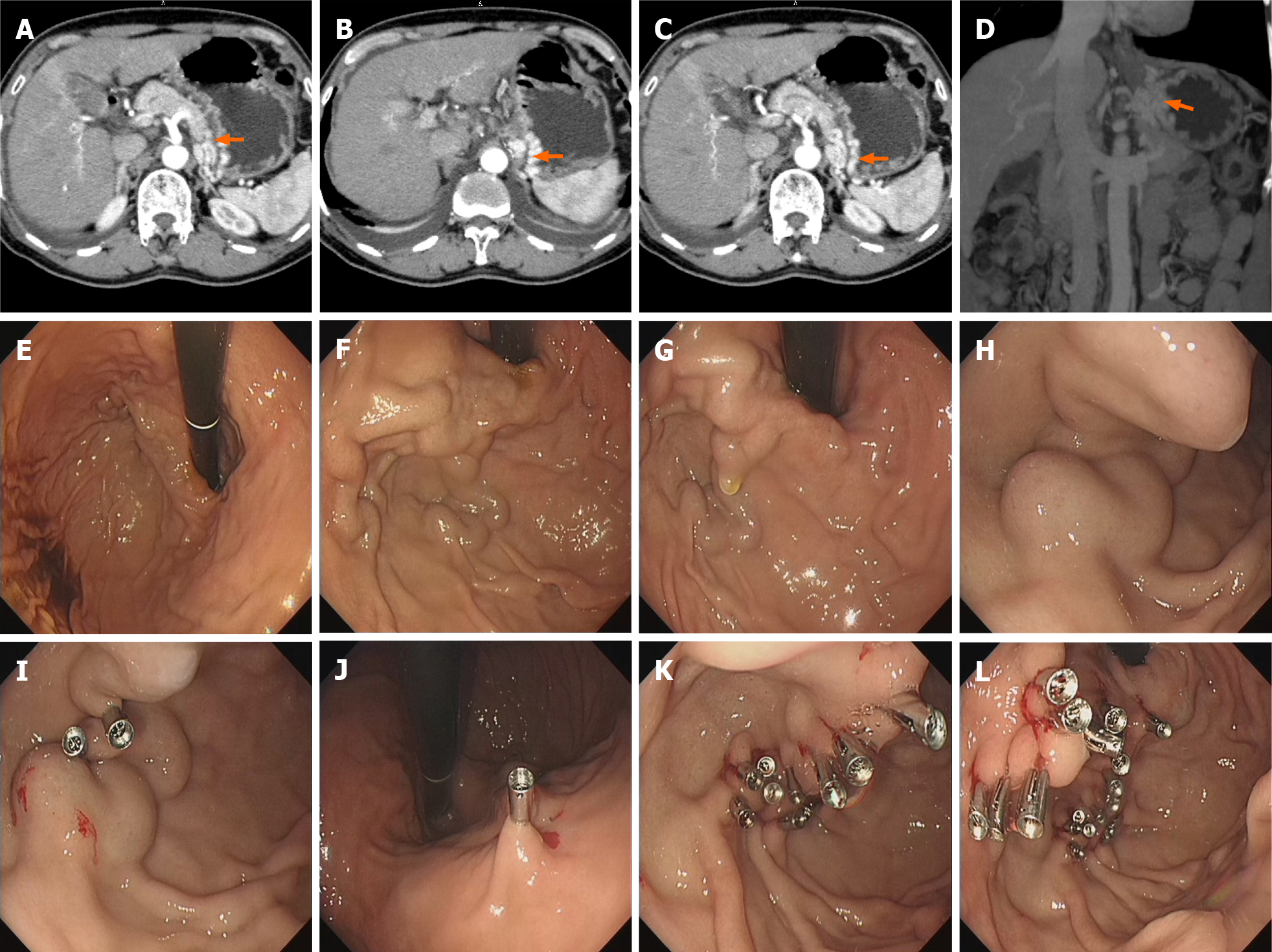

Chest computed tomography (CT) showed inflammation in the middle lobe of the right lung, and an enhanced upper abdominal CT showed gastric varices (Figure 1A-D).

The patient was diagnosed with hepatitis B cirrhosis-related GOV bleeding.

The patient and their family members refused emergency endoscopy as they were worried about endoscopy related complications. At the same time, blood transfusion therapy with 1000 mL of packed red blood cells, acid suppressive agents (lanso

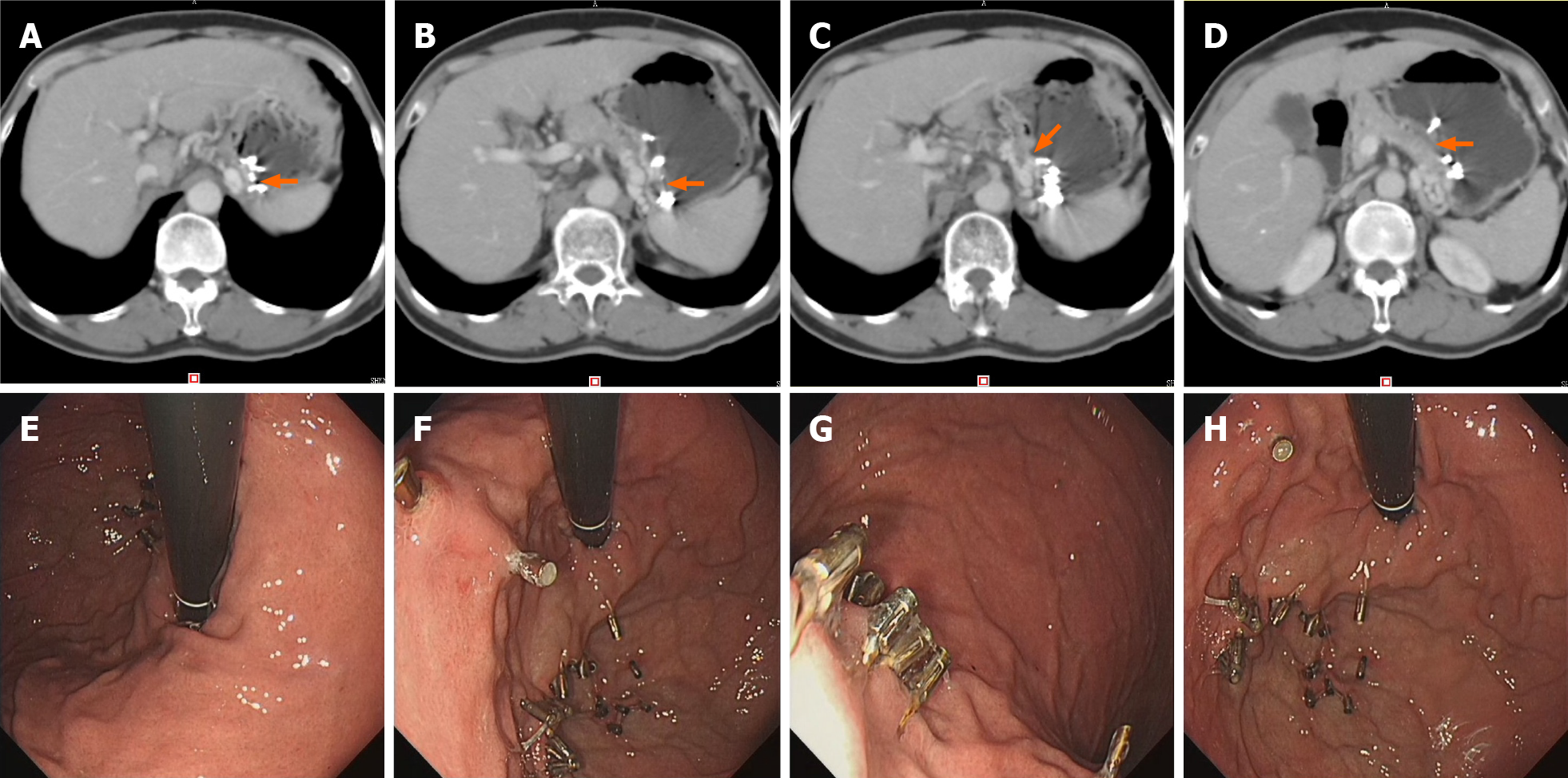

The patient had no black stools on the 2nd postoperative day and was discharged a week after operation. He had no further episodes of gastrointestinal bleeding with a normal hemoglobin level and liver function tests noted at the 5th month of follow-up. Follow-up imaging showed significantly improved gastric varices (Figure 2A-D), and the follow-up endoscopy showed well-healed gastric varices at the 5th postoperative month (Figure 2E-H).

This retrospective case report was approved by the ethics review board of Shenzhen Shiyan People's Hospital (Approval no. 2021SZSY-01). The patient provided written informed consent for the participation and publication of this report. He was satisfied with the treatment received.

A new method of endoscopic therapy using metal clips for the secondary prevention of bleeding from gastric varices in patients with cirrhosis was devised. Our study expands the clinical application of endoscopic clipping and offers a new solution for secondary prophylaxis of bleeding from gastric varices. The results suggested that our endoscopic clip method is safe, inexpensive, easy, and effective and was well tolerated by a patient with GOV 2.

EVC appears to be an effective technique for the secondary prophylaxis of bleeding from GOV 2. During the procedure, the endoscope did not have to be withdrawn, simplifying the operation by shortening the surgical time while minimizing medical risks. In addition, metal clips are more cost-efficient than tissue adhesives and sclerosing agents and have good histocompatibility; furthermore, their safety and efficacy profile in endoscopic hemostasis has garnered more approval in the literature. Employing EVC not only simplifies the endoscopy but precludes the need for surgery and long-term conventional treatment. Mitsunaga et al[13] reported 82 prophylactic (primary prevention) EVCs without variceal progression in 89.9% with good security. Miyoshi et al[14] first reported EVC applied prophylactically to 9 patients with esophageal (rather than gastric) varices without major complications such as massive bleeding, achieving the desired effect. In this case, we utilized EVC for the secondary prophylaxis of gastric varices with encouraging results.

We believe that EVC is suitable for LDRf Type D 1.0-2.0 gastric varices and GOV 2, which are long, nodular, and tortuous veins that are continuous with esophageal varices[3]. Following the flow direction of varicose veins, metal clips were used by clipping both ends of the vein; this effectively blocks part of the blood flow, resulting in vessel collapse. The clips should be applied gently and released slowly to avoid pulling the veins. The time of shedding of the clips was longer, and more clips were required for simple EVC. Somatostatin was then employed, which reduces splanchnic blood flow, decreases portal venous pressure, and improves the safety and efficacy of the endoscopic procedure[2]. EVC relieves gastric varices and decreases portal vein pressures, so we had expected liver function to improve. The patient had normal liver function at postoperative five-month follow-up, indicating that our theory was correct.

However, there were some EVC complications, such as uncorrected hemorrhagic shock, uncontrolled hepatic encephalopathy, and uncooperative patients, that must also be considered. Therefore, future large-scale randomized controlled trials would be prudent to provide qualitative evidence and confirm the efficacy of EVC for secondary prophylaxis in bleeding from gastric varices.

In conclusion, gastrointestinal bleeding can be a fatal complication of portal hypertension. Endoscopic techniques play a critical role in the prevention of variceal rebleeding. We propose that EVC is a safe and effective method for the secondary prophylaxis of GOV 2. Our report supports endoscopic clipping as an important treatment modality in the secondary prophylaxis of GOV. However, additional research is needed to confirm its long-term safety and efficacy.

| 1. | Ibrahim M, Mostafa I, Devière J. New Developments in Managing Variceal Bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:1964-1969. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Xu X, Ding H, Jia J, Wei L, Duan Z, Ling-Hu E, Liu Y, Zhuang H. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of esophageal and gastric variceal bleeding in cirrhotic portal hypertension. Chinese Journal of Liver Diseases (Electronic Version). 2016;1:1-18. |

| 3. | Sarin SK, Lahoti D, Saxena SP, Murthy NS, Makwana UK. Prevalence, classification and natural history of gastric varices: a long-term follow-up study in 568 portal hypertension patients. Hepatology. 1992;16:1343-1349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 789] [Cited by in RCA: 873] [Article Influence: 25.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (42)] |

| 4. | Bai XS, Yang B, Yu YJ, Liu HL, Yin Z. Cerebral air embolism following an endoscopic variceal ligation: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e10965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhang X, Liu X, Yang M, Dong H, Xv L, Li L. Occurrence of infective endocarditis following endoscopic variceal ligation therapy: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e4482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Trudeau W, Prindiville T. Endoscopic injection sclerosis in bleeding gastric varices. Gastrointest Endosc. 1986;32:264-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Irisawa A, Obara K, Sato Y, Saito A, Orikasa H, Ohira H, Sakamoto H, Sasajima T, Rai T, Odajima H, Abe M, Kasukawa R. Adherence of cyanoacrylate which leaked from gastric varices to the left renal vein during endoscopic injection sclerotherapy: a histopathologic study. Endoscopy. 2000;32:804-806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bhat YM, Weilert F, Fredrick RT, Kane SD, Shah JN, Hamerski CM, Binmoeller KF. EUS-guided treatment of gastric fundal varices with combined injection of coils and cyanoacrylate glue: a large U.S. experience over 6 years (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:1164-1172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Liu S, Wu N, Chen M, Zeng X, Wang F, She Q. Neurological symptoms and spinal cord embolism caused by endoscopic injection sclerotherapy for esophageal varices: A case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e0622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hayashi T, Yonezawa M, Kawabara T. The study on stanch clips for the treatment by endoscopy. Gastroenterol Endosc. 1975;17:92-101. |

| 11. | Hachisu T. Evaluation of endoscopic hemostasis using an improved clipping apparatus. Surg Endosc. 1988;2:13-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhu WH, Jiang HG, Liu J. [Application of metal clip with endoscopic treatment for difficult cases of immediate hemostasis of esophagogastric variceal bleeding]. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2020;28:266-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mitsunaga T, Yoshida H, Kouchi K, Hishiki T, Saito T, Yamada S, Sato Y, Terui K, Nakata M, Takenouchi A, Ohnuma N. Pediatric gastroesophageal varices: treatment strategy and long-term results. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:1980-1983. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Miyoshi H, Shikata J, Tokura Y. Endoscopic clipping of esophageal varices. Dig Endosc. 1992;4:147-150. |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited manuscript; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Batyrbekov K, Oda M S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH