Published online Nov 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i32.12045

Peer-review started: August 20, 2022

First decision: September 5, 2022

Revised: September 7, 2022

Accepted: October 12, 2022

Article in press: October 12, 2022

Published online: November 16, 2022

Processing time: 80 Days and 4.9 Hours

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare disease of unknown etiology. LCH involving the thymus is mainly seen in pediatric patients and is extremely rare in adults. In this report, we describe a rare case of LCH originating from the thymus in an adult.

A 56-year-old man was admitted in April 2022 with complaints of intermittent dizziness since 2020, which had worsened in the previous 10 d. The physical chest examination was negative, and there was a history of hypertension for > 2 years. Chest computed tomography showed a nodular soft tissue density shadow in the anterior mediastinum measuring approximately 13 mm × 9 mm × 8 mm. Postoperative pathological findings confirmed the diagnosis of LCH.

It is challenging to differentiate LCH involving the thymus from thymoma in imaging features. Pathological biopsy remains the gold standard when an anterior mediastinal occupying lesion is found.

Core Tip: Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is an infrequent clinical hematological disorder. The gold standard for diagnosis is surgical biopsy for pathological examination and immunohistochemical analysis. We report a rare case of LCH with monosystemic involvement, which, when combined with previous case reports of LCH, reveals that LCH involving only the thymus is extremely rare in adults. The imaging features are similar to those of thymoma and may provide additional diagnostic ideas in the detection of anterior mediastinal occupations.

- Citation: Li YF, Han SH, Qie P, Yin QF, Wang HE. Langerhans cell histiocytosis involving only the thymus in an adult: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(32): 12045-12051

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i32/12045.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i32.12045

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a group of immature dendritic cell proliferation disorders with complex pathogenesis that has not yet been defined[1]. LCH can affect almost all systems, with the most commonly affected organs include bones, skin, pituitary, liver, spleen, bone marrow, lungs, and lymph nodes. LCH involving the adult thymus is extremely rare. Its clinical manifestations include pain, splenomegaly, fever, cough, polyhydramnios, headache, protruding eyes, enlarged lymph nodes, unstable walking, and even neuropsychiatric symptoms. It has a low incidence and can be seen in any age group, mostly in children, but in adults, it is most insidious, often with a chronic course, and the specific treatment is not yet validated[2]. In this case report, we present an adult patient with a highly suspicious thymoma of anterior superior mediastinum, with a postoperative pathological diagnosis of LCH involving only the thymus.

A 56-year-old man was admitted to the hospital with intermittent dizziness, and chest computed tomography (CT) suggested an anterosuperior mediastinal lesion.

The patient was admitted to our Cardiology Department on March 31, 2022 with suspected hypertension because of intermittent dizziness for 2 years, aggravated for > 10 d. Routine chest CT indicated an occupying lesion of about 13 mm × 9 mm × 8 mm in the superior anterior mediastinum, which was highly suspected to be a thymoma after consultation with our Department of Thoracic Surgery. After blood pressure was stabilized, the patient was referred to our department for surgery to clarify the nature of the lesion.

The patient was previously treated with surgery for thyroid nodules at a local hospital 3 years ago, with no other specific medical history or history of particular medications.

The patient denied any family history of related diseases. He has been drinking alcohol for > 20 years (400 mL/time).

On physical examination, the vital signs were as follows: Body temperature, 36.7 °C; blood pressure, 167/100 mmHg; heart rate, 80 beats per min; respiratory rate, 18 breaths per min. No positive signs on chest examination.

Laboratory examination results showed no abnormalities.

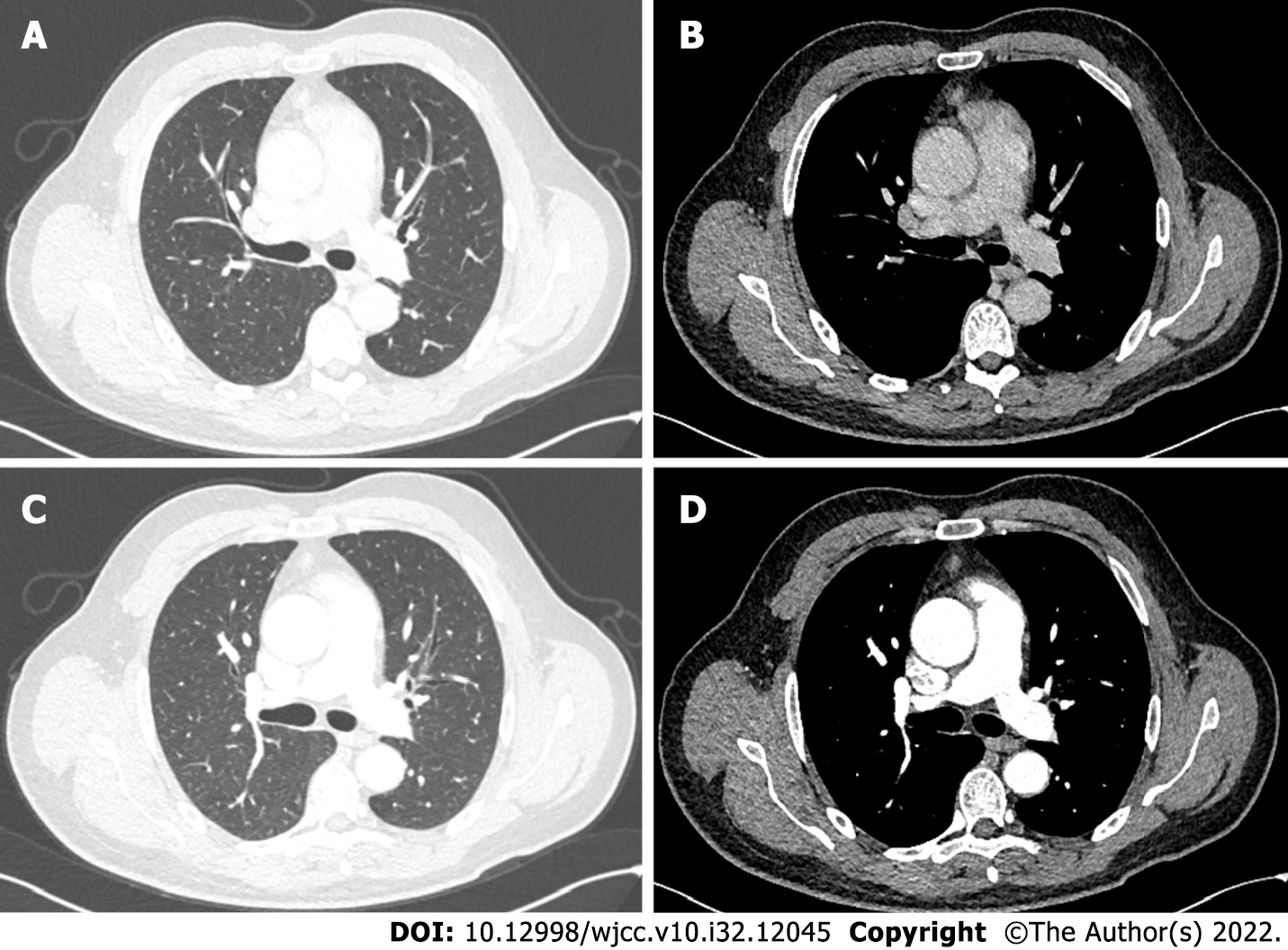

Chest CT on admission showed a nodular soft tissue density shadow in the anterior mediastinum of about 13 mm × 9 mm × 8 mm, and a more uniform enhancement was seen on the enhancement scan, with CT values of 38, 63 and 61 HU in the two phases of scanning and enhancement, respectively (Figure 1). The skin and bones showed no abnormalities, and no relevant clinical manifestations such as muscle weakness. No significant abnormal finding were seen on cranial CT and abdominal ultrasound.

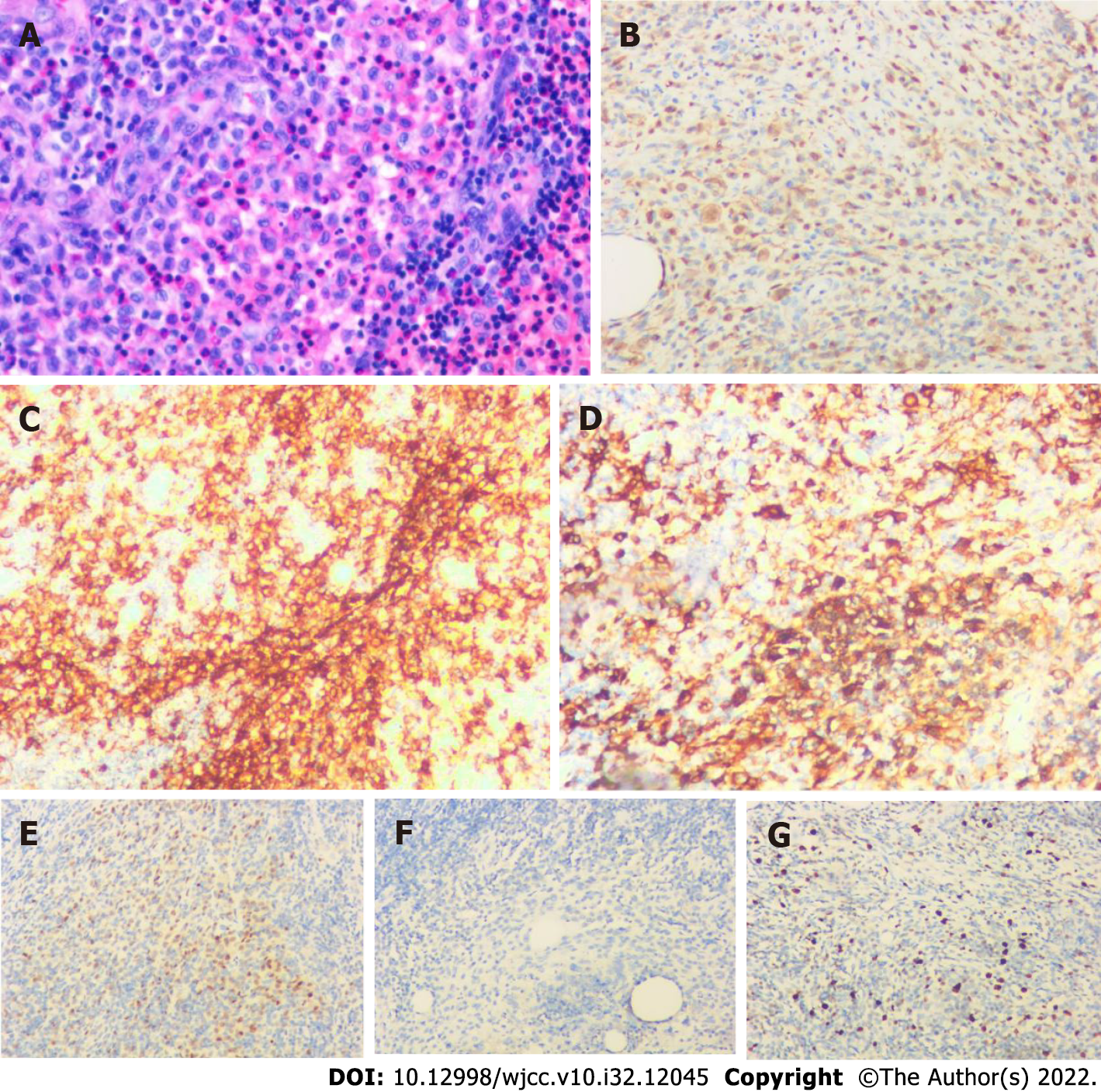

We considered the possibility of thymoma before the operation, and after obtaining consent from the patient and family, we performed a right thoracoscopic resection of the anterior mediastinal mass and sampled three nearby lymph nodes. Postoperative pathological findings showed that the nodule was approximately 1.3 cm × 0.9 cm × 0.8 cm in size, with solid gray–white slightly hard and poorly defined cut surface and gray–yellow surrounding the tissue cut surface. Combined immunohistochemical staining supported LCH with surrounding thymic tissue. Immunohistochemical staining showed: S100 (+), CD1a (+), CD68 (partial +), CD163 (partial +), cyclin D1 (+), CD21 (-), and Ki-67 (active area about 25% +). There were three lymph nodes with reactive hyperplasia (Figure 2).

Based on clinical presentation, imaging, and pathological findings, the final diagnosis of LCH with thymic involvement was established.

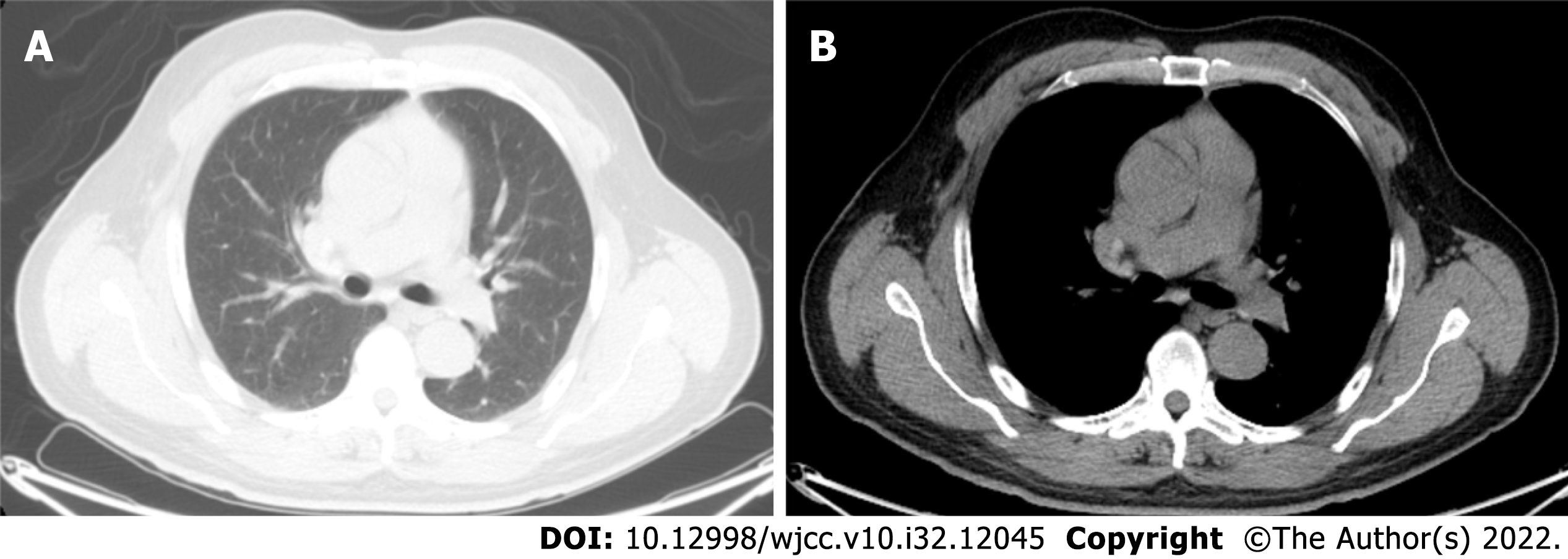

After excision of the lesion and a comprehensive assessment of the patient’s overall condition, the patient was referred to the Hematology Department, where further positron emission tomography (PET)/CT, cranial enhancement magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and bone marrow examination revealed no other lesions (Figure 3). The patient was considered to have LCH involving only the thymus. Considering that the patient had only a single systemic involvement, clinical observation was continued, and no recurrence or metastasis was observed 3 mo after surgery.

Chest CT at 3 mo postoperatively showed good healing (Figure 4). At the time of writing, the patient is still being followed up.

LCH is a rare proliferative disorder of the dendritic and reticulocyte systems, which belongs to the category of histiocytic neoplasms in hematological diseases, and is characterized by abnormal proliferation of cells of the monocyte–phagocyte system and tissue infiltration as the main pathological features[3]. Lesions can involve almost every system of the body. According to the latest National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, LCH can be classified by its clinical characteristics and the extent of lesion involvement into four types: Single system, pulmonary-involved, multisystem with risk organ involvement, and multisystem without risk organ involvement[4].

The pathogenesis associated with LCH is not yet clear, and most believe that the cause may be related to immune dysfunction, cytokine mediation, viral infection, smoking, and genetic factors. LCH is essentially a group of myeloid tumors of LC origin[5], and studies in recent years have identified mutations in the proto-oncogene BRAF-V600E in LC of LCH patients, further supporting the idea that LCH is a clonal neoplastic disease[6], and since then mutations in alternative activating mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway genes have been identified. The condition is more common in children, with an incidence of 4–8 cases per million people, while LCH in adults is rare, with an incidence of only one or two cases per million people, mostly in men, with a male to female ratio of about 3.7:1[7,8]. Common sites of LCH involvement include the bones, skin, pituitary gland, liver, spleen, bone marrow, lungs, and lymph nodes[9]. In most cases, in older children and adults, LCH presents with monosystemic involvement, usually involving the skeleton. In adults with a long smoking history, the lungs are also vulnerable[10], less frequently affecting the skin, lymph nodes, etc., and more rarely the thymus.

The diagnosis of LCH is mainly based on clinical and radiological findings, with acute onset in pediatric patients and insidious onset and milder symptoms in adult patients. In this case, there was no special discomfort, and the physical examination showed negative results. Only an occupying lesion in the anterior mediastinum was found during routine chest CT, and further investigation was performed to clarify the nature of the lesion. According to the literature, LCH occurring in the thymus of children mostly shows an abnormal enlargement of the thymus and mostly punctate calcifications on CT[11]. Due to the continuous degeneration of the thymus with age, LCH involving the thymus is extremely rare in adults. There is no literature that systematically describes the relevant features of LCH occurring in the thymus of adults on CT. Among the anterior mediastinal masses, lesions caused by tumors of the thymus, lymph nodes, and germ cells are more common. Benign thymoma mostly appears on CT as a round or oval mass in the superior anterior mediastinum with clear and lobulated margins and mostly uniform density. In contrast, malignant thymoma (type B) mostly appears as a lobulated or irregularly shaped mass with unclear margins, loss of fatty lines, uneven density, and susceptibility to cystic transformation and necrosis[12]. However, in this case, CT showed nodule-like soft tissue density shadow with unclear marginal boundaries, and the enhancement scan showed more uniform enhancement, which caused a significant problem for the initial diagnosis of the disease. For diagnosing LCH, histopathological examination remains the gold standard, and surgical biopsy and histological analysis are mandatory in most cases to plan the best treatment[13]. In the pathological presentation of LCH, the inflammatory background is usually myeloid in the spectrum and contains abundant eosinophils. LCH consistently expresses S100 and cyclin D1 and has mutations in genes leading to excessive activation of MAPK pathways[14]. CDla is a differentiating antigen of LC with persistent, stable expression, and it is considered the best choice for identifying human peripheral blood and bone marrow dendritic cells. The finding of Birbeck granules or positive CDla antigen in lesioned cells by electron microscopy is the most compelling evidence for diagnosing LCH[10]. In this case, we surgically removed the anterior mediastinal space and sampled the nearby lymph nodes, and it was through pathological examination of the tissue and immunohistochemical staining that the results indicated positive S100 and CDla antigens in the thymus tissue, and the preliminary diagnosis was LCH. The diagnosis of LCH involving only the thymus was confirmed by PET/CT, cranial MRI and bone marrow aspiration after surgery.

The prognosis of LCH is closely related to the patient’s age at onset, the number of organs involved, the degree of functional impairment, and response to treatment, with a better clinical prognosis for low-risk LCH. There is no standard therapy for adult LCH, and no prospective trials have been conducted in this population; treatment of adult LCH is based on pediatric treatment criteria. In patients with single-system involvement of LCH, surgical resection to remove the lesion and postoperative combination with radiotherapy or local chemotherapy to reduce the recurrence of the disease, depending on the assessment of the disease, are most feasible and most patients can survive for a long time[15]. High-risk patients with involvement of bone marrow, liver, spleen and other organs are mostly treated with systemic chemotherapy regimens but still have a high recurrence rate. Some studies have reported that hematopoietic stem cell transplantation can improve the survival rate of patients with refractory LCH. The post-transplantation survival rate (55%) is significantly higher than the overall survival rate (20%)[16]. It is now considered that hematopoietic stem cell transplantation can be used as a remedial treatment after the failure of chemotherapy for refractory LCH.

In this case of primary adult thymic LCH, there were no obvious clinical symptoms, no significant abnormalities on physical examination and routine laboratory tests, and imaging findings were difficult to differentiate from thymoma. The onset of the disease is insidious, and surgical biopsy and pathology remain the gold standard for confirming the diagnosis. Due to the scarcity of clinical data, this case may have important clinical implications, suggesting new ideas for initial diagnosis when anterior mediastinal occupying lesions are found. That attention should be paid to rarely involved sites and commonly involved organs when screening for LCH lesions.

| 1. | Rodriguez-Galindo C. Clinical features and treatment of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Acta Paediatr. 2021;110:2892-2902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Krooks J, Minkov M, Weatherall AG. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children: History, classification, pathobiology, clinical manifestations, and prognosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1035-1044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Baraban E, Cooper K. Histiocytic and dendritic cell neoplasms of the mediastinum. Mediastinum. 2020;4:12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Go RS, Jacobsen E, Baiocchi R, Buhtoiarov I, Butler EB, Campbell PK, Coulter DW, Diamond E, Flagg A, Goodman AM, Goyal G, Gratzinger D, Hendrie PC, Higman M, Hogarty MD, Janku F, Karmali R, Morgan D, Raldow AC, Stefanovic A, Tantravahi SK, Walkovich K, Zhang L, Bergman MA, Darlow SD. Histiocytic Neoplasms, Version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19:1277-1303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Allen CE, Ladisch S, McClain KL. How I treat Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2015;126:26-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Varga E, Korom I, Polyánka H, Szabó K, Széll M, Baltás E, Bata-Csörgő Z, Kemény L, Oláh J. BRAFV600E mutation in cutaneous lesions of patients with adult Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1205-1211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | El Demellawy D, Young JL, de Nanassy J, Chernetsova E, Nasr A. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a comprehensive review. Pathology. 2015;47:294-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Laurencikas E, Gavhed D, Stålemark H, van't Hooft I, Prayer D, Grois N, Henter JI. Incidence and pattern of radiological central nervous system Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children: a population based study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56:250-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Emile JF, Abla O, Fraitag S, Horne A, Haroche J, Donadieu J, Requena-Caballero L, Jordan MB, Abdel-Wahab O, Allen CE, Charlotte F, Diamond EL, Egeler RM, Fischer A, Herrera JG, Henter JI, Janku F, Merad M, Picarsic J, Rodriguez-Galindo C, Rollins BJ, Tazi A, Vassallo R, Weiss LM; Histiocyte Society. Revised classification of histiocytoses and neoplasms of the macrophage-dendritic cell lineages. Blood. 2016;127:2672-2681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 722] [Cited by in RCA: 1049] [Article Influence: 104.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Wang X, Yang S, Tu P, Li R. A case of Langerhans cell histiocytosis in an adult with initial symptoms confined to the skin. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:337-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lakatos K, Herbrüggen H, Pötschger U, Prosch H, Minkov M. Radiological features of thymic langerhans cell histiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:E143-E145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Detterbeck FC, Zeeshan A. Thymoma: current diagnosis and treatment. Chin Med J (Engl). 2013;126:2186-2191. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Cantu MA, Lupo PJ, Bilgi M, Hicks MJ, Allen CE, McClain KL. Optimal therapy for adults with Langerhans cell histiocytosis bone lesions. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Jain N, Virk SS, Phillips FM, Yu E, Khan SN. A 90-day Bundled Payment for Primary Single-level Lumbar Discectomy/Decompression: What Does "Big Data" Say? Clin Spine Surg. 2018;31:120-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Minkov M, Grois N, Heitger A, Pötschger U, Westermeier T, Gadner H. Treatment of multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Results of the DAL-HX 83 and DAL-HX 90 studies. DAL-HX Study Group. Klin Padiatr. 2000;212:139-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Lai CC, Huang WC, Cheng SN. Successful treatment of refractory Langerhans cell histiocytosis by allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2008;12:99-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Agrawal P, United States; Sedaghattalab M, Iran S-Editor: Liu GL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu GL