Published online Nov 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i31.11625

Peer-review started: July 20, 2022

First decision: August 4, 2022

Revised: August 15, 2022

Accepted: September 22, 2022

Article in press: September 22, 2022

Published online: November 6, 2022

Processing time: 99 Days and 0.9 Hours

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is a form of temporary vertigo induced by moving the head to a specific position. It is a self-limited, peripheral, vestibular disease and can be divided into primary and secondary forms. Congenital nystagmus (CN), an involuntary, rhythmic, binocular-symmetry, conjugated eye movement, is found at birth or within 3 mo of birth. According to the pathogenesis, CN can be divided into sensory-defect nystagmus and motor-defect nystagmus. The coexistence of BPPV and CN is rarely seen in the clinic.

A 62-year-old woman presented to our clinic complaining of a 15-d history of recurrent positional vertigo. The vertigo lasting less than 1 min occurred when she turned over, sometimes accompanied by nausea and vomiting. Both the patient and her father had CN. Her spontaneous nystagmus was horizontal to right; however, the gaze test revealed variable horizontal nystagmus with the same degree when the eyes moved. The patient’s Dix-Hallpike test was normal, except for persistent nystagmus, and the roll test showed severe variable horizontal nystagmus, which lasted for about 20 s in the same direction as her head movement to the right and left, although the right-side nystagmus was stronger than the left-side. Since these symptoms were accompanied by nausea, she was diagnosed with BPPV with CN and treated by manual reduction.

Though rare, if BPPV with CN is correctly identified and diagnosed, reduction treatment is comparably effective to other vertigo types.

Core Tip: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is defined as a disorder of the inner ear characterized by repeated episodes of positional vertigo. Congenital nystagmus (CN), an involuntary, rhythmic, binocular-symmetry, conjugated eye movement, is found at birth or within 3 mo of birth. BPPV with CN is rarely seen in the clinic. CN should be distinguished from other pathologic nystagmus types. BPPV can be accurately determined through postural nystagmus. We report the characteristics of BPPV with CN, further explaining how to identify nystagmus.

- Citation: Li GF, Wang YT, Lu XG, Liu M, Liu CB, Wang CH. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo with congenital nystagmus: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(31): 11625-11629

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i31/11625.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i31.11625

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is defined as a disorder of the inner ear characterized by repeated episodes of positional vertigo[1]. BPPV is among the common diseases that cause aural vertigo, and 24.1% of patients with dizziness or vertigo are diagnosed with BPPV[2]. Spontaneous nystagmus refers to a continuous, involuntary, and rhythmic movement of the eyeball in the absence of inducing factors and is divided into congenital nystagmus (CN) and acquired nystagmus. The latter is a type of nystagmus commonly seen in the clinic. CN is an ocular motor disorder in which patients are afflicted by periodic involuntary ocular oscillations affecting both eyes[3,4]. It develops during the first 3 to 6 mo of a patient’s life and has a prevalence of 14 per 10000 people in the United Kingdom[5]. The etiology of CN is largely unknown, but we know that most patients have lifelong nystagmus, although it can gradually relieve with age in some patients. Some BPPV patients present with spontaneous nystagmus, but BPPV with CN is rare: To date, we have not seen such cases reported. In this report, we present the case of a BPPV patient with CN and her nystagmus findings.

A 62-year-old woman presented at our clinic, complaining of positional vertigo that had recurred for 15 d.

Fifteen days previously, the patient’s symptoms had begun with severe dizziness when she rose, which recurred when she rolled over or lied down. She sometimes experienced nausea and vomiting at the onset of these symptoms.

The patient was physically healthy in the past.

Both the patient and her father had a history of CN.

The patient’s physical examination revealed no abnormal findings.

The patient did not undergo laboratory examinations.

The patient did not undergo imaging examinations.

The patient was ultimately diagnosed with BPPV with CN.

The patient was prescribed a barbecue roll maneuver to treat her right, lateral, semicircular canal BPPV of geotropic type. This treatment required her to lie down with the affected ear facing downward. Then, she rolled over to the opposite side for 90 degrees until she returned to the original position. Her vertigo symptoms disappeared after the therapy.

The patient’s follow-up comprised three telephone appointments at 1 wk, 1 mo, and 6 mo after treatment. She was asymptomatic, without any recurrence of vertigo.

BPPV is generally categorized as posterior semicircular canal, anterior semicircular canal, and horizontal semicircular canal types. Of these categories, posterior semicircular canal BPPV is the most common (affecting 80%-90% of patients), followed by horizontal semicircular canal BPPV (10%-20%), while anterior semicircular canal BPPV is rare (3%)[6,7]. The Dix-Hallpike maneuver is considered the gold standard test to diagnose posterior canal BPPV, and the supine roll test is considered the gold standard for diagnosing horizontal semicircular canal BPPV[8]. Upbeat-torsional nystagmus is provoked by vertical semicircular canal BPPV.

The pathogenesis of BPPV remains unclear; however, risk factors include age, mental stress, osteoporosis, insomnia, and hypertension[9,10]. Currently, the following two theories are widely accepted. First, canalithiasis suggests that when the head is moved relative to gravity, otoliths residing on the macula utriculi migrate into the semicircular canal and are displaced relative to the semicircular canal wall because of gravity, causing endolymph flow and resulting in the deviation of the cupula terminalis and, in turn, corresponding signs and symptoms. When the otolith moves due to gravity to the lowest point in the semicircular canal lumen, the endolymph stops, the cupula terminalis returns to its original position, and signs and symptoms disappear.

Second, eupulolithiasis suggests that the detached otoliths on the macula utriculi adhere to the cupula terminalis, changing the density of the latter relative to the endolymph and making it sensitive to gravity, resulting in the corresponding symptoms and signs[11]. CN usually occurs at birth or within 3 mo of birth. Although this nystagmus persists throughout most patients’ lives, some patients’ symptoms gradually relieve with age. CN is divided into two categories. The first is congenital motor defect nystagmus, in which eye movement includes fast and slow phases. The second is congenital sensory defect nystagmus, also known as “pendular nystagmus”, in which the eye moves at one speed. CN is clinically rare, with an incidence of about 0.005%-0.286%[3]. To our knowledge, BPPV with CN has not been previously reported.

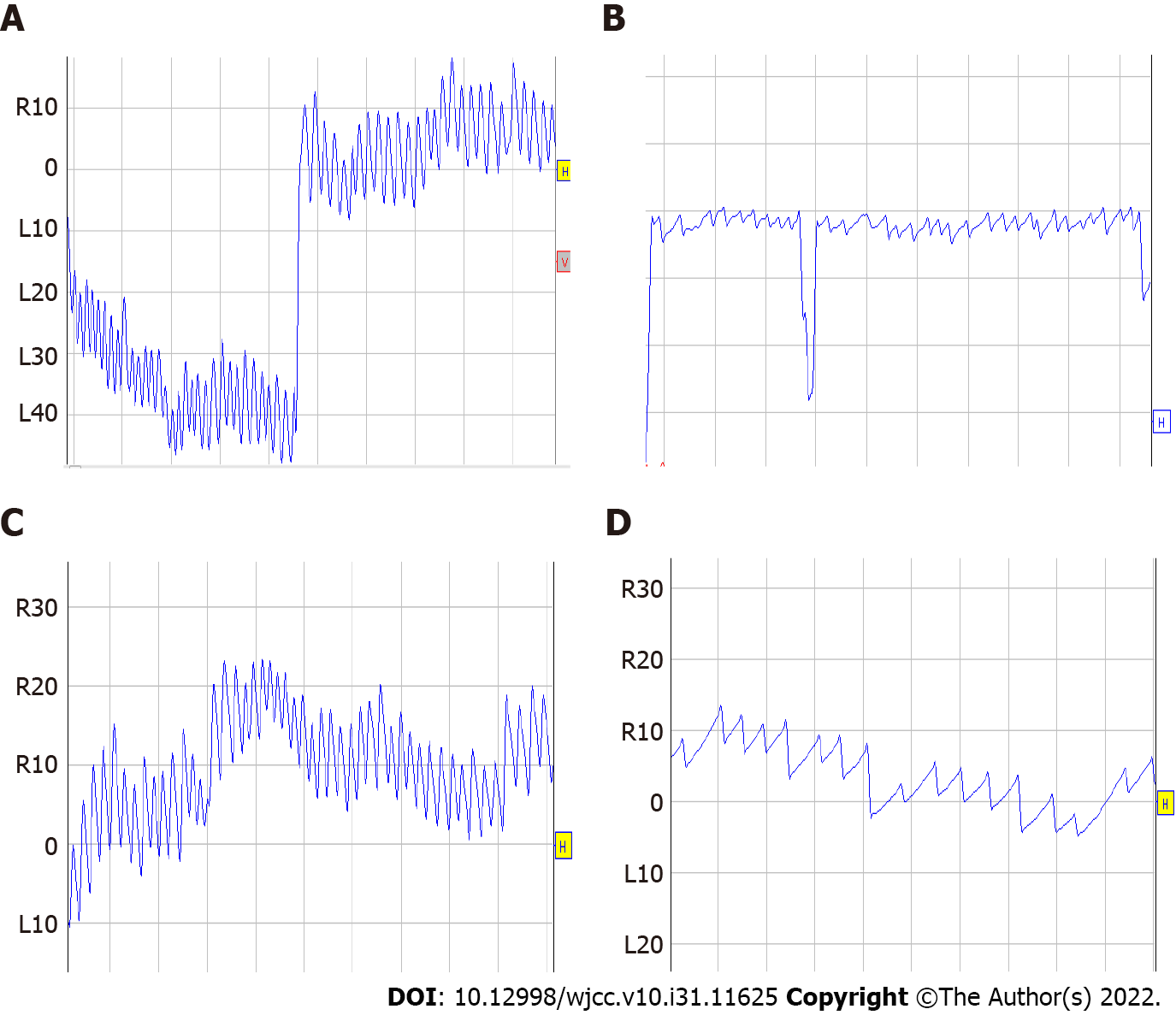

In the United States, according to statistics, about 5.6 million patients clinically complain of dizziness per year, and 17%-42% of patients with vertigo are diagnosed with BPPV[12-14]. BPPV treatment can be categorized as canalith repositioning maneuvers or vestibular rehabilitation[1]. Diagnosis of horizontal semicircular canal BPPV relies on the supine roll test. During examinations, clinicians should observe whether the direction of the nystagmus is geotropic or apogeotropic and which side of the nystagmus is stronger to enable identification of the patient’s affected side. In our case, the Dix-Hallpike test showed the signs of horizontal nystagmus without vertigo and geotropic nystagmus, which was stronger on her right side during the roll test (Figure 1). Unlike other patients with BPPV, she exhibited persistent horizontal nystagmus on the right side after intense nystagmus lasting more than 10 s, which was accompanied by vertigo. The lasting nystagmus is suggestive of CN, which is similar to that observed in patients with spontaneous nystagmus but absent in BPPV patients without spontaneous nystagmus. Spontaneous nystagmus is very common clinically among patients with vertigo.

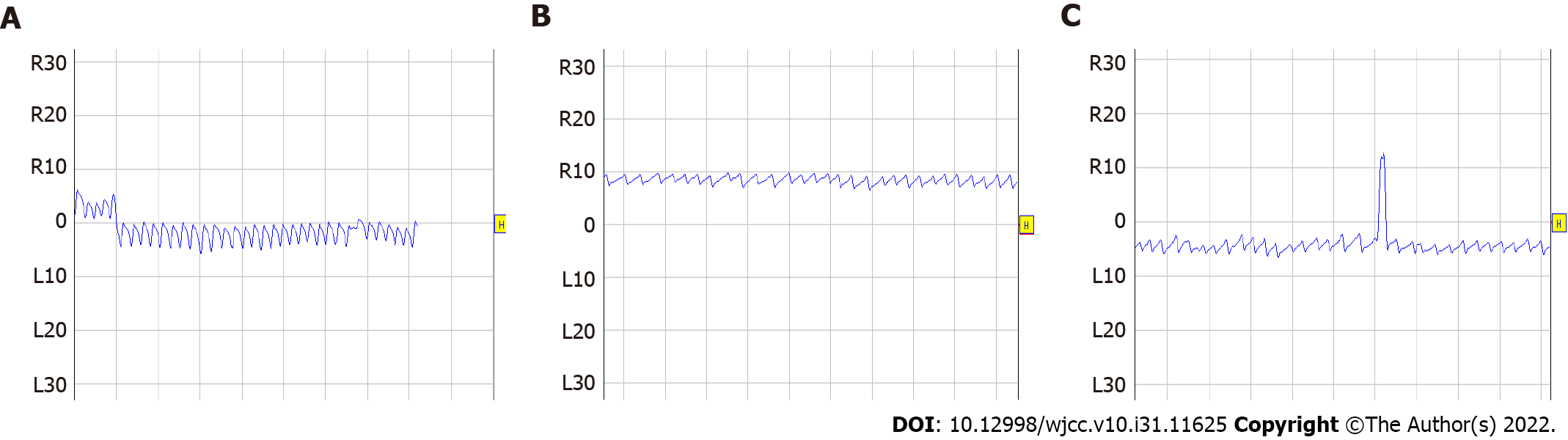

The following aspects should be used to distinguish CN from other central and peripheral spontaneous forms of nystagmus. The first and most important is a patient’s medical history. Nystagmus is always present during CN; someone in the patient’s family will have CN because of the heritability of the disease, while other types of spontaneous nystagmus only appear at the onset of the disease. Second, the direction of peripheral nystagmus is constant, while that of CN is variable. The test can be conducted with Frenzel glasses to observe the nystagmus accurately. The direction of the nystagmus will be seen to remain the same in the peripheral nystagmus; however, the direction of the nystagmus is consistent with the eye movement in central nystagmus and variable nyatagmus in CN (Figure 2). Third, a CN patient usually experiences horizontal nystagmus of variable intensity, while other pathologic central nystagmus types may entail vertical and horizontal nystagmus with generally persistent intensity.

CN is rare in the clinic. If individuals experience spontaneous nystagmus with constant intensity and variable direction, a careful medical history should be taken to eliminate CN, which may influence the diagnosis. The treatment for BPPV with CN is the same as that for BPPV. In the case reported here, the patient was diagnosed with BPPV with CN, and the result was good.

| 1. | Bhattacharyya N, Gubbels SP, Schwartz SR, Edlow JA, El-Kashlan H, Fife T, Holmberg JM, Mahoney K, Hollingsworth DB, Roberts R, Seidman MD, Steiner RW, Do BT, Voelker CC, Waguespack RW, Corrigan MD. Clinical Practice Guideline: Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (Update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;156:S1-S47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 337] [Cited by in RCA: 363] [Article Influence: 40.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kim HJ, Lee JO, Choi JY, Kim JS. Etiologic distribution of dizziness and vertigo in a referral-based dizziness clinic in South Korea. J Neurol. 2020;267:2252-2259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Casteels I, Harris CM, Shawkat F, Taylor D. Nystagmus in infancy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1992;76:434-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Abadi RV, Bjerre A. Motor and sensory characteristics of infantile nystagmus. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:1152-1160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Proudlock FA, Gottlob I. Nystagmus in childhood. In: Hoyt C, Taylor D. Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, 4th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2013: 922-932. |

| 6. | Kim JS, Zee DS. Clinical practice. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1138-1147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 241] [Cited by in RCA: 291] [Article Influence: 24.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hornibrook J. Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV): History, Pathophysiology, Office Treatment and Future Directions. Int J Otolaryngol. 2011;2011:835671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Fife TD, Iverson DJ, Lempert T, Furman JM, Baloh RW, Tusa RJ, Hain TC, Herdman S, Morrow MJ, Gronseth GS; Quality Standards Subcommittee, American Academy of Neurology. Practice parameter: therapies for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2008;70:2067-2074. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 245] [Cited by in RCA: 229] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Byun H, Chung JH, Lee SH, Park CW, Kim EM, Kim I. Increased risk of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in osteoporosis: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Sci Rep. 2019;9:3469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chen J, Zhang S, Cui K, Liu C. Risk factors for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo recurrence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol. 2021;268:4117-4127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Editorial Board of Chinese Journal of Otorhinolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery; Chinese Medical Association of Otorhinolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. Clinical Guidelines: Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo. Chin J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;52:173-177. |

| 12. | Schappert SM. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 1989 summary. Vital Health Stat 13. 1992;1-80. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Katsarkas A. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV): idiopathic versus post-traumatic. Acta Otolaryngol. 1999;119:745-749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hanley K, O'Dowd T, Considine N. A systematic review of vertigo in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51:666-671. [PubMed] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Bhandari A, United States; Faraji N, Iran S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Wang JJ