Published online Oct 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i29.10779

Peer-review started: July 12, 2022

First decision: August 4, 2022

Revised: August 17, 2022

Accepted: September 4, 2022

Article in press: September 4, 2022

Published online: October 16, 2022

Processing time: 78 Days and 19.4 Hours

The co-existence of Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia (WM) with internodal marginal zone lymphoma (INMZL) is rare and often associated with poor prognosis.

We present a Chinese female patient who developed secondary light chain amyloidosis due to WM and INMZL and provides opinions on its systemic treat

A detailed clinical evaluation and active identification of the aetiology are recom

Core Tip: Waldenström's macroglobulinemia (WM) is a lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, and internodal marginal zone lymphoma (INMZL) is another rare subtype of clinically inertial non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. We report a rare secondary light chain amyloidosis case due to WM and INMZL. We also retrieved related articles indexed in PubMed. Bortezomib-based therapy, including bortezomib, dexamethasone, and zanubrutinb, was administered for two months, and treatment efficacy was evaluated as partial remission. Treatment should be based on the patient's physiological age, life expectancy, and tolerance to treatment. Therefore, we recommend detailed clinical evaluation and active identification of the etiology to avoid missed diagnosis and misdiagnosis.

- Citation: Zhao ZY, Tang N, Fu XJ, Lin LE. Secondary light chain amyloidosis with Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia and intermodal marginal zone lymphoma: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(29): 10779-10786

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i29/10779.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i29.10779

Waldenström's macroglobulinemia (WM), accounting for 2% of non-Hodgkin's lymphomas (NHLs), is a lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma that secretes immunoglobulin M (IgM). WM is an inertial lymphoma, but most patients eventually progress and require new drugs to improve their prognosis. Internodal marginal zone lymphoma (INMZL) is another relatively rare subtype of clinically inertial NHL, most commonly seen in adults, with a mostly atypical presentation. It can easily be misdiagnosed in the early stage as its symptoms are nonspecific in patients suffering from comorbid WM and INMZL. This report aims to describe our pathological observations and review the literature to improve our understanding of the disease, avoid misdiagnosis and provide evidence on clinical prognosis and treatment.

A 65-year-old woman was admitted to a local hospital due to increased blood sedimentation during a physical examination six years ago.

The patient was admitted to our hospital due to signs of oedema in both lower limbs, tachycardia, and lymphadenectasis one year ago.

She was admitted to a local hospital due to increased blood sedimentation during physical examination six years ago without pain and discomfort. Fever, splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and musculoskeletal complaints were absent, and she was subsequently diagnosed with WM but did not receive treatment due to the absence of symptoms. However, the regular review was performed as recom

Serum protein electrophoresis demonstrated significantly dark stained bands in the Y region, a negative P53 mutation by fluorescence in situ hybridization, and a normal chromosome karyotype. Bone marrow biopsy indicated an increased proportion of heterogeneous lymphocytes with an abnormal cell population accounting for 14.03% of the nucleated cells in the flow cytology of bone marrow and abnormal B lymphocytes expressing CD19, CD20, CD79b, CD23, CD200, CD1d, sign, sign, lambda, and partially expressing CD5 and CD38. Bone marrow immunophenotyping indicated that abnormal cells accounted for approximately 14.03% of the nucleated cells, and abnormal B lymphocytes expressed CD19, CD20, CD79b, CD23, CD200, CDId sign, sign, and lambda. Despite the absence of the MYD88 L265P mutation, the diagnosis of WM was made based on the above results, and the patient received Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor monotherapy for two years.

The patient denied a family history of malignant tumors.

On physical examination, her vital signs were as follows: Body temperature, 36.3 °C; blood pressure, 118/70 mmHg; heart rate, 82 bpm; respiratory rate, 19 breaths/min. She was pale and had signs of oedema in both lower limbs on examination.

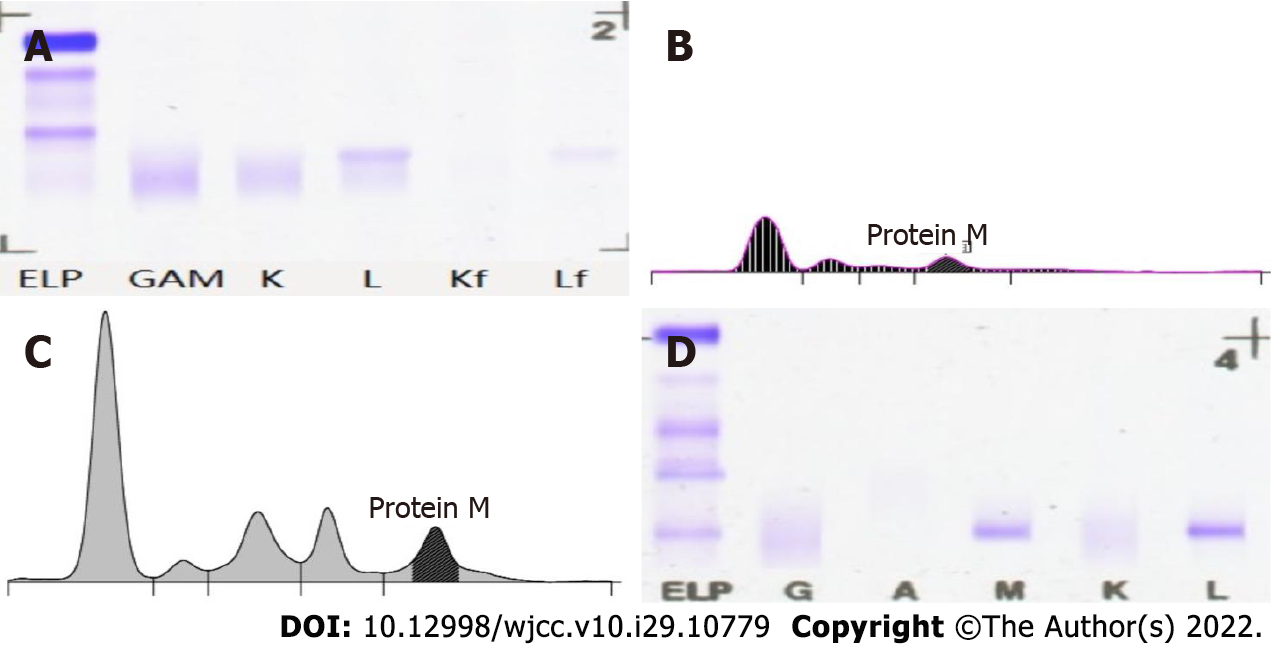

The patient was admitted to our hospital due to signs of oedema in both lower limbs, tachycardia, and lymphadenectasis one year ago. Complete blood counts revealed moderate anaemia (80 g/dL). Biochemical tests demonstrated hypoproteinemia (16.8 g/L), normal lactate dehydrogenase (128.4 U/L), and increased IgM (36.60 g/L) and light chain λ (5.82 g/L). Serum beta-2-microglobulin (4.79 mg/L) was also above normal (Table 1). Bone marrow smears showed an increased ratio of mature lymphocytes (68.0). Flow cytometry analysis of the bone marrow revealed abnormal cells that were HLA-DR+, CD19+, CD20+, and CD79b+, strongly suggesting a mature B-cell neoplasm. Serum protein electrophoresis demonstrated an “M” component of 21.83 g/L with a severe immunoparesis with band typing as IgM kappa (serum IgM 41.20 g/L) (Figure 1).

| Laboratory results | |

| WBC | 7.55 × 109/L |

| RBC | 3.23 × 1012/L |

| Plt | 347 × 109/L |

| INR | 1.09 |

| FIB | 12.36 g/L |

| HBeAg | Negative |

| β-2 microglobulin | 4.79 mg/L |

| Urinary albumin | 7233.20 mg/24 h |

| IgA | 0.11 g/L |

| K | 3.80 mmol/L |

| Glu | 4.70 mmol/L |

| Cr | 80 μmmol/L |

| Alb | 16.8 g/L |

| T-bil | 2.70 μmmol/L |

| ALT | 7.8 U/L |

| TG | 1.20 mmol/L |

| NETU | 5.44 × 109/L |

| Hb | 90 g/L |

| PT | 13.3 s |

| TT | 15.2 s |

| APTT | 43.1 s |

| HIV | Negative |

| UAIb | 5605.60 mg/24 h |

| IgG | 1.77 g/L |

| IgM | 36.60 g/L |

| Na | 136.0 mmol/L |

| UA | 413 μmmol/L |

| TP | 59.5 g/L |

| Glob | 42.7 g/L |

| IBIL | 0.99 μmmol/L |

| AST | 13.2 U/L |

| CRP | 27.44 |

Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose) confirmed a maximum standardized uptake value of 2.9 in the bilateral submandibular, bilateral cervical, bilateral axillary, mediastinal, and bilateral inguinal multiple lymph nodes.

An allele-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay was carried out to detect the MYD88 L265P mutation and the mutation, frequency was 29.2% (sequencing depth 1890 ×). Immunohistochemical staining was carried out on bone marrow (BM) biopsies which showed lymphocytosis (75%), indicative of lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma involvement in the BM. Bone marrow fluid specimens were cultured and analyzed for 20 mid-phase cells, five of which showed karyotypes with partial short arm deletion of chromosome 1, suspected partial short arm deletion of chromosome 4, and one missing chromosome 6, with an additional marker chromosome, attached.

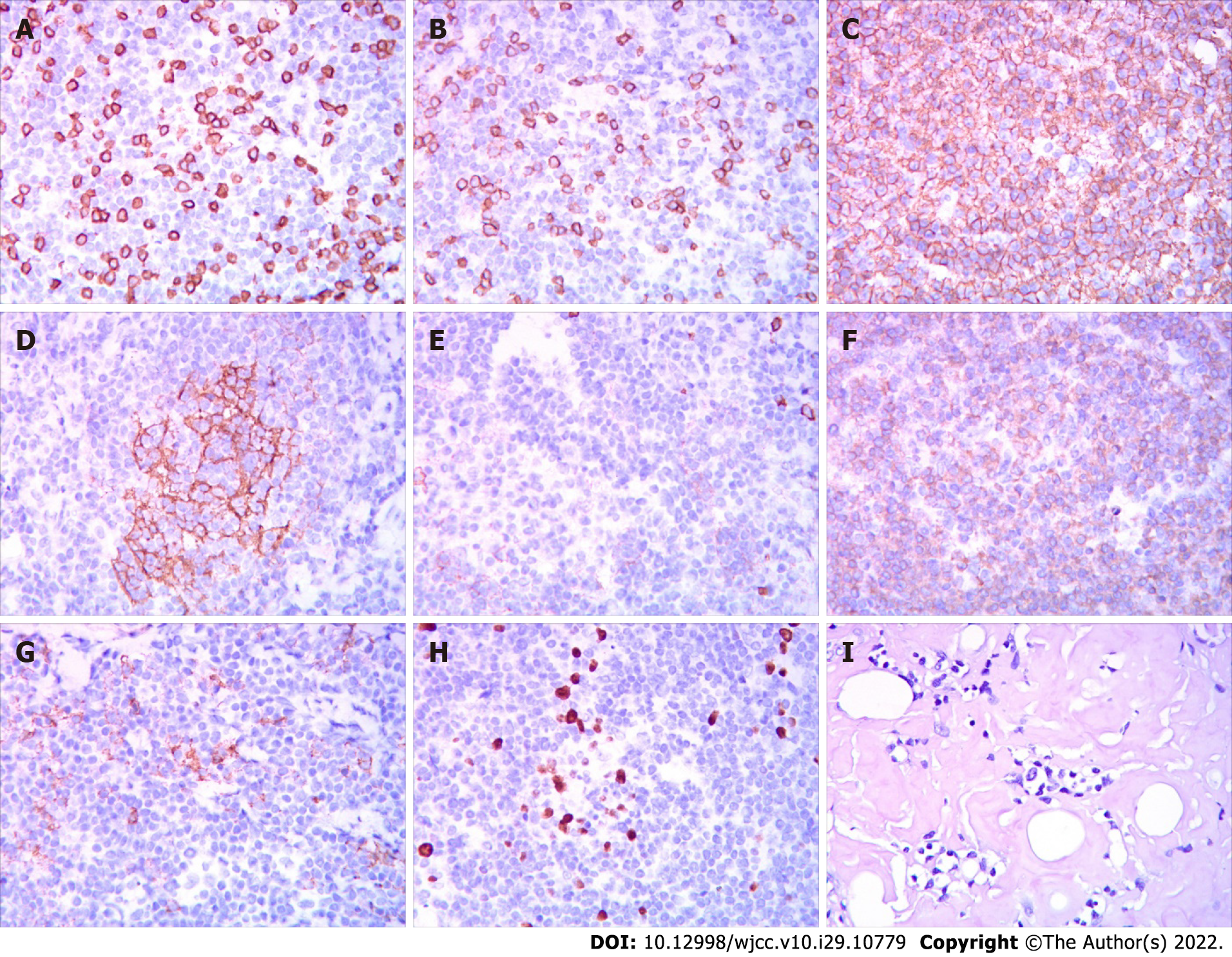

A left cervical lymph node biopsy was performed on December 1, 2021. Histological examination of the biopsy specimens using hematoxylin and eosin staining demonstrated proliferation of predominantly small-sized abnormal lymphoid cells, and these cells were MUM1 (multiple +), CD138 (-), Kappa (individual +), CD20 (multiple +), PAX5 (+), CD3 (few +), CD56 (scattered +), Cyc1in D1 (one), CD79a (multiple +), CD21 (FDC shrinkage), CD5 (few +), and Ki67 (GC+, scattered + around), and Congo red (+/-) on immunohistochemistry (Figure 2). Epstein-Barr virus-encoded small RNA in situ hybridization was negative. The PCR-IG gene rearrangement test (400bp) showed the following: IgHV-FR1 (-), IgHV-FR2 (-), IgHV-FR3 (-), IgK-Vk-Jk (+), and IgK-Kde+INTR-Kde (+). Remarkably, the patient showed oedema, hypoproteinemia, increased plasma creatinine, 3+ urine protein, and 7233.20 mg total protein in a 24-h urine collection. The results of the left cervical lymph node biopsy stained with Congo red were positive/negative for amyloid, and the results of the BM biopsy stained with Congo red were negative; therefore, amyloidosis complicated by renal injury was suspected, which required fat aspiration and a renal biopsy for confirmation, but the patient refused.

To investigate whether WM and INMZL in this patient had the same origin, we planned to perform immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH) gene rearrangement analyses of the BM and lymph node using PCR of laser micro-dissected samples from a formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded section. However, as the patient still refused this assessment, we could not to exclude the possibility of a composite lymphoma.

The patient’s medical history combined with her test results, diagnosed with WM and INMZL, with concomitant amyloid renal damage.

The patient was scheduled to receive the BC regimen (rituximab 375 mg/m2 monthly for 6-8 courses, bendamustine 90 mg/m2 per day × 2, monthly for aix courses). However, toxic side effects, allergic reactions, infection, and systemic reactions were observed after two courses. After the first chemotherapy course, the patient experienced mild diarrhoea and low-grade fever for two weeks. Unfortunately, she developed moderate pleural effusion and dyspnea and could not lie flat; two chest drainage tubes were urgently placed in the bilateral pleural cavities for more than one month. Grade 1-2 myelosuppression was observed after chemotherapy, and moderate fever was treated with intravenous antibiotics. Thus, alternative therapy options were considered, and bortezomib-based therapy, including bortezomib, dexamethasone, and zanubrutinb, was administered for two months. Oedema in both lower limbs was relieved and treatment efficacy was evaluated as partial remission.

The patient is still alive at the time of publication.

Jan Waldenstrom first described macroglobulinemia in 1944. WM is characterized by infiltration of the bone marrow with lymphoplasmacytic cells, excessive production of a monoclonal IgM protein, and associated clinical features such as anaemia, lymphadenopathy, and serum hyperviscosity[1]. As an uncommon lymphoid neoplasm, WM has low morbidity, with an overall annual age-adjusted 3.8 cases per million persons per year. Therefore, WM is easily misdiagnosed as other B-cell lymphomas and monoclonal gammopathies of undetermined significance[2].

The patient in this report was diagnosed with WM and received BTK inhibitor monotherapy for two years. The treatment of WM has progressed from traditional treatment with benzodiazepine, CHOP, and the FC regimen to new treatments based on rituximab, proteasome inhibitors, and BTK inhibitors[3]. Over the past ten years, our centre has gradually increased the proportion of patients on new treatment regimens. These patients receiving new treatments had significantly longer overall and progression-free survival than those receiving traditional treatment. Zanubrutinib, a Food and Drug Administration-approved drug for WM, has demonstrated comparable efficacy in hematologic response with improved side effects compared to other BTK inhibitors. Therefore, we chose this drug to treat our patient and achieved an improved short-term curative effect. The patient developed painless and progressive enlargement of superficial lymph nodes after two years of oral zanubrutinib treatment. WM can be combined with superficial lymph node enlargement, but the lymph nodes do not develop progressive enlargement. These symptoms suggested that the patient did not have WM alone but had disease progression or transformation to other diseases; therefore, we carried out lymph node biopsies and other related tests.

INMZL, a rare condition diagnosed based on histology, accounts for fewer than 2% of all lymphoid neoplasms and approximately 10% of marginal zone B-cell lymphomas (MZL), according to the American Society of Hematology[4]. The immunohistochemical and histopathological findings confirmed INMZL in our patient, with many peripheral zone B cells expressing CD1d and secreting mainly IgM[4]. Due to similar laboratory results, differential diagnosis is particularly difficult between WM and INMZL, which can secrete IgM. Although MYD88 mutations are present in most patients with WM, they are not specific; MYD88 mutations are seen in 5% to 10% of patients with lymph node MZL[5]. The lymph node biopsy was dominated by small lymphocytes, with abundant cells, small size, visible germinal centre-like structures, and CD20+[6]. In the present case, the final diagnosis of INMZL was thus established, which was not an insignificant result.

The patient's INMZL diagnosis was established, but proteinuria, hypoproteinemia and bilateral lower extremity oedema persisted. WM-related renal damage is clinically rare, mostly manifesting as mild to moderate M proteinuria with microscopic hematuria, renal insufficiency, and rare nephrotic syndrome, with less than 3% of WM patients progressing to end-stage renal disease[7]. The literature reports monoclonal immunoglobulin A-associated renal damage in about 81% of cases, including light chain amyloidosis (21.5%), non-amyloid glomerulopathy (33.0%) and tubulointerstitial lesions (26.5%), non-amyloid glomerulopathy (33.0%) and tubulointerstitial lesions (16.5%); lymphoma infiltration was the most common tubulointerstitial lesion (19%), other tubular lesions include tubulointerstitial nephropathy and light chain proximal tubulopathy[8].

Secondary light chain amyloidosis can occur in 10% to 15% of patients with multiple myeloma, and in patients with WM or INMZL. Primary light chain amyloidosis is distinguished from secondary light chain amyloidosis primarily by whether the patient can meet the relevant diagnostic criteria for the disease[9]. Our patient's diagnosis of amyloidosis was confirmed by examination, which may be secondary to WM or INMZL. MW-related renal impairment is rare, accounting for 5.1% to 8% of patients with MW, and is usually characterized by low to moderate M proteinuria with microscopic hematuria, renal failure, and nephrotic syndrome, with less than 3% of patients with MW developing the end-stage renal disease[10]. Although the patient did not have a renal puncture biopsy, we concluded that the patient had combined renal amyloidosis by lymph node biopsy, and 24-h urine protein level greater than 0.5 g. We did not confirm this diagnosis by biopsy, which is a shortcoming in this case.

Chemotherapy with rituximab (R)-based regimens, such as rituximab + cyclophosphamide + dexamethasone or bendamustine + R (BR), is preferred for those whose main symptom is WM-related hematocrit disorder or organomegaly, which can reduce tumour load more rapidly[11]. There are no effective treatment options for light chain amyloidosis due to NHL, which include rituximab mono

WM combined with INMZL followed by amyloidosis is rare. The clinical presentation lacks specificity, requiring detailed clinical evaluation and active identification of the aetiology to avoid missed diagnosis and misdiagnosis. A pathological biopsy is a gold standard for confirming the diagnosis of this disease. There is no effective treatment, and zanubrutinib + bortezomib has shown partial efficacy, but the long-term prognosis is unknown. Regular follow-up and timely treatment are important to prolong the survival of patients.

The authors are grateful to Dr. Gao ZF for the pathological diagnosis and providing us with the photomicrographs.

| 1. | Hassab-El-Naby HMM, El-Khalawany M, Rageh MA. Cutaneous macroglobulinosis with Waldenström macroglobulinemia. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:771-775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ababneh O, Abushukair H, Qarqash A, Syaj S, Al Hadidi S. The Use of Bruton Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Waldenström's Macroglobulinemia. Clin Hematol Int. 2022;4:21-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rodrigues CD, Peixeiro RP, Viegas D, Chorão P, Couto ME, Gaspar CL, Fernandes JP, Alves D, Ribeiro LA, de Vasconcelos M P, Tomé AL, Badior M, Coelho H, Príncipe F, Chacim S, da Silva MG, Coutinho R. Clinical Characteristics, Treatment and Evolution of Splenic and Nodal Marginal Zone Lymphomas-Retrospective and Multicentric Analysis of Portuguese Centers. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2021;21:e839-e844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | King IL, Fortier A, Tighe M, Dibble J, Watts GF, Veerapen N, Haberman AM, Besra GS, Mohrs M, Brenner MB, Leadbetter EA. Invariant natural killer T cells direct B cell responses to cognate lipid antigen in an IL-21-dependent manner. Nat Immunol. 2011;13:44-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wang J, Yan Y, Xiong W, Song G, Wang Y, Zhao J, Jia Y, Li C, Yu Z, Yu Y, Chen J, Jiao Y, Wang T, Lyu R, Li Q, Ma Y, Liu W, Zou D, An G, Sun Q, Wang H, Xiao Z, Wang J, Qiu L, Yi S. Landscape of immunoglobulin heavy chain gene repertoire and its clinical relevance to LPL/WM. Blood Adv. 2022;6:4049-4059. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zucca E, Arcaini L, Buske C, Johnson PW, Ponzoni M, Raderer M, Ricardi U, Salar A, Stamatopoulos K, Thieblemont C, Wotherspoon A, Ladetto M; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Electronic address: clinicalguidelines@esmo.org. Marginal zone lymphomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:17-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 35.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Comenzo RL, Reece D, Palladini G, Seldin D, Sanchorawala V, Landau H, Falk R, Wells K, Solomon A, Wechalekar A, Zonder J, Dispenzieri A, Gertz M, Streicher H, Skinner M, Kyle RA, Merlini G. Consensus guidelines for the conduct and reporting of clinical trials in systemic light-chain amyloidosis. Leukemia. 2012;26:2317-2325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 248] [Cited by in RCA: 304] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Vos JM, Gustine J, Rennke HG, Hunter Z, Manning RJ, Dubeau TE, Meid K, Minnema MC, Kersten MJ, Treon SP, Castillo JJ. Renal disease related to Waldenström macroglobulinaemia: incidence, pathology and clinical outcomes. Br J Haematol. 2016;175:623-630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Javaugue V, Debiais-Delpech C, Nouvier M, Gand E, Chauvet S, Ecotiere L, Desport E, Goujon JM, Delwail V, Guidez S, Tomowiak C, Leleu X, Jaccard A, Rioux-Leclerc N, Vigneau C, Fermand JP, Touchard G, Thierry A, Bridoux F. Clinicopathological spectrum of renal parenchymal involvement in B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders. Kidney Int. 2019;96:94-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Uppal NN, Monga D, Vernace MA, Mehtabdin K, Shah HH, Bijol V, Jhaveri KD. Kidney diseases associated with Waldenström macroglobulinemia. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2019;34:1644-1652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Dimopoulos MA, Kastritis E. How I treat Waldenström macroglobulinemia. Blood. 2019;134:2022-2035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zanwar S, Abeykoon JP. Treatment paradigm in Waldenström macroglobulinemia: frontline therapy and beyond. Ther Adv Hematol. 2022;13:20406207221093962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Fazilat-Panah D, Iran; Karki S, Nepal; Trifan A, Romania S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: A P-Editor: Gao CC