Published online Sep 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i27.9693

Peer-review started: June 2, 2022

First decision: July 14, 2022

Revised: July 18, 2022

Accepted: August 15, 2022

Article in press: August 15, 2022

Published online: September 26, 2022

Processing time: 105 Days and 21.7 Hours

Retroperitoneal sarcoma (RPS) is a rare malignancy arising from mesenchymal cells that most commonly presents as an abdominal mass and is associated with poor prognosis. Although several studies have assessed the survival benefits of wide excision, few have reported detailed methods for achieving wide excision in patients with RPS.

To describe our experience with multidisciplinary surgical resection of RPS using intra- and extra-pelvic approaches.

Multidisciplinary surgery is an anatomical approach that combines intra- and extra-peritoneal access within the same surgery to achieve complete RPS removal. This retrospective review of the records of patients who underwent multidisciplinary surgery for RPS analyzed surgical and survival outcomes.

Eight patients underwent 10 intra- and extra-pelvic surgical resections, and their median mass size was 12.75 cm (range, 6-45.5 cm). Using an intrapelvic approach, laparoscopy-assisted surgery was performed in four cases and laparotomy surgery in six. Using an extrapelvic approach, ilioinguinal and posterior ap

RPS is therapeutically challenging because of its location and high risk of recurrence. Therefore, intra- and extra-pelvic surgical approaches can improve the macroscopic security of the surgical margin.

Core Tip: Retroperitoneal sarcomas (RPS) are therapeutically challenging because of their location and high risk of recurrence. Multidisciplinary surgery is an anatomical approach that combines intra- and extra-peritoneal access within the same surgery to achieve complete RPS removal. This retrospective review of the records of eight patients who underwent multidisciplinary surgery for RPS analyzed surgical and survival outcomes. All patients’ RPS masses were removed completely, and four achieved R0 resection through intra- and extra-pelvic surgery. Therefore, intra- and extra-pelvic surgical approaches can improve the macroscopic security of the surgical margin.

- Citation: Song H, Ahn JH, Jung Y, Woo JY, Cha J, Chung YG, Lee KH. Intra and extra pelvic multidisciplinary surgical approach of retroperitoneal sarcoma: Case series report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(27): 9693-9702

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i27/9693.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i27.9693

Retroperitoneal sarcoma (RPS) is a rare malignancy arising from mesenchymal cells that most com

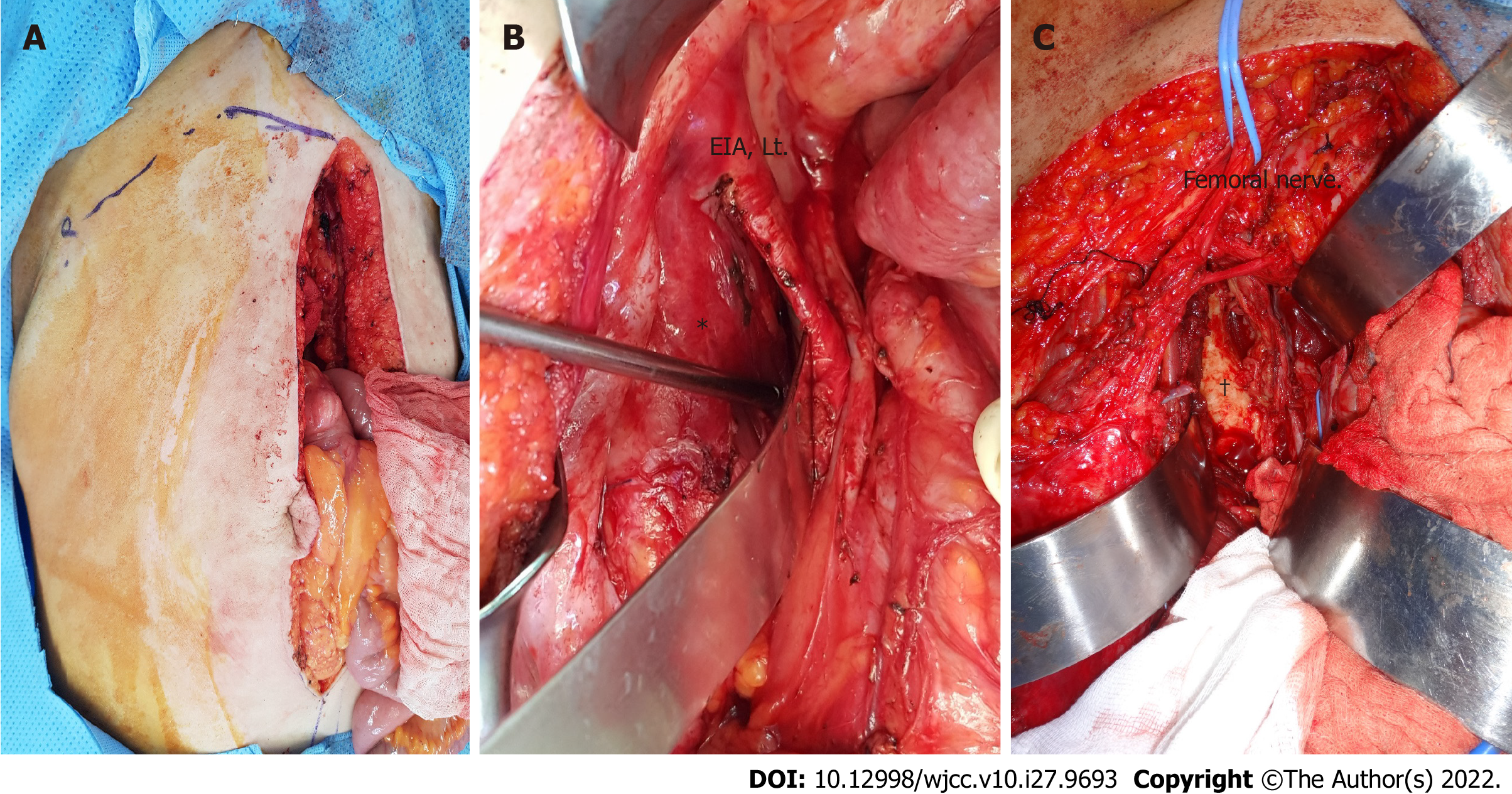

Although several studies have assessed the survival benefits of wide excision, few have reported detailed methods for achieving wide excision in patients with RPS. Therefore, the present study aimed to describe our experience with multidisciplinary surgical resection in patients with RPS, including intra- and extra-pelvic approaches. Our multidisciplinary surgical approach used an anatomical approach for tumor removal, combining intra- and extra-peritoneal RPS access (Figures 1 and 2). Although this two-step approach is more invasive than the conventional approach, it is a potential solution to overcome the surgical limitations of the anatomic location in the retroperitoneal space.

Eligible patients seen at Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital, College of Medicine at The Catholic University of Korea, were identified based on their surgical history of RPS. Only patients who underwent surgical treatment using intra- and extra-pelvic approaches were included in the current study, regardless of their disease state. We evaluated medical records between January 2001 and February 2020, including patient age, body mass index (BMI), mass size, use of neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatments, final histology following surgical resection and outcomes [i.e., approach method, estimated blood loss, overall survival (OS), and progression-free survival (PFS) for each treatment]. The size of the retroperitoneal mass was reported based on its long axis. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital (approval number: KC20RISI0350).

Ten intra- and extra-pelvic surgical treatments were administered to eight patients in September 2014. The patients’ mean age and BMI were 42.75 years (range, 14-78 years) and 22.4 (range, 17.6-24), respectively. The median mass size was 12.75 cm (range: 6-45.5 cm). The masses extended from the intra- to the retroperitoneal areas. Palpable mass or pain at specific sites was reported as the initial symptom in four patients. Three patients underwent multidisciplinary surgery as the primary surgical resection, whereas the others underwent a secondary or greater surgical resection (Table 1). Before surgery, all cases were discussed regarding resectability, necessary pre-operative procedures, and predicted complications in a multidisciplinary cooperative center at the Department of Oncology, Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital. In routine systems, contact with specialized doctors is available at every surgical time, owing to hospital policy. Another surgical team could be requested to join our surgery at any time during the operation.

| Characteristics | Value |

| Mean age (yr) | 42.75 ± 18.4 |

| Mean BMI | 22.4 ± 2.4 |

| Initial symptoms, n (%) | |

| Palpable mass | 4 (50) |

| Pain on the specific site | 4 (50) |

| Median mass size (long axis, cm) | 12.75 ± 11.7 |

| Order of surgery, n (%) | |

| Primary | 3 (30) |

| Secondary | 2 (20) |

| Tertiary | 2 (20) |

| More than tertiary | 3 (30) |

| History of neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment, n (%) | |

| Neoadjuvant treatment | 2 (25) |

| Adjuvant treatment | 8 (100) |

| Surgical outcome | |

| Median overall survival (mo, median) | 64.6 |

| Progression-free survival (mo, median) | 13.7 |

| Died patients due to disease, n (%) | 2 (25) |

| Pathology, n (%) | |

| Liposarcoma | 2 (25) |

| Leiomyosarcoma | 1 (12.5) |

| Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor | 1 (12.5) |

| Osteosarcoma | 2 (25) |

| Chondrosarcoma | 1 (12.5) |

| Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma | 1 (12.5) |

For the intrapelvic approach, laparoscopy-assisted surgery was performed on four patients, and laparotomy surgery with midline incision was performed on six. For the extrapelvic approach, ilioinguinal and posterior approaches were used in four patients, while the prone position and midline skin incision were shared in one. In all 10 procedures, wide or marginal mass excision was performed, with resection of suspicious tumor invasion structures. The pelvic organs (sigmoid colon and external or internal iliac vessels) were dissected and mobilized by several specialized doctors. Pelvic lymph node dissections, prophylactic fixation, or revision of the structures were performed. In all 10 cases, a median of three surgical teams (range, 2-5 teams) cooperated to remove the RPS. The colorectal or vascular team of general surgery, gynecologic oncology team, bone tumor or spine part of orthopedic surgery, and urology doctors participated in multidisciplinary surgery (Table 2).

| PN | Number of surgery | Intra pelvic surgery | Extra pelvic surgery | Pathology | Resection margin | EBL (mL) | HD (d) | OS (mo) | PFS (mo) | |

| Approach method and operation title | Approach method and operation title | Intra pelvic surgery | Extra pelvic surgery | |||||||

| 1 | Primary surgery | Laparoscopy | Posterior approach of hip | WDLPS | R0 | R0 | 300 | 15 | 65.3 | 13.7 |

| Mass excision | Wide excision | |||||||||

| 1 | Secondary surgery | Laparotomy | Laparotomy | WDLPS | R1 | R1 | 2000 | 17 | 65.3 | 50 |

| Mass excision | Marginal excisionneurolysis | |||||||||

| Dissection and mobilization of Lt. internal iliac vessel | ||||||||||

| Ligation of Lt. iliac vein | ||||||||||

| 2 | 5th surgery | Laparotomy | Ilioinguinal approach | LMS | R1 | R0 | 1250 | 19 | 97 | 9 |

| Mass excision | Wide excision | |||||||||

| 3 | Secondary surgery | Laparoscopy | Ilioinguinal approach | MPNST | R0 | R1 | 10000 | 42 | 63.9 | 4.3 |

| Rt. RSO and PLND | Wide excision | |||||||||

| Sigmoid colon mobilization | ||||||||||

| Dissection of Rt. external and internal iliac vessel | ||||||||||

| 4 | Primary surgery | Laparotomy | Posterior approach of hip | Myxoid liposarcoma | R0 | R1 | 2000 | 16 | 55.7 | 49 |

| Mass excision | Wide excision neurolysis | |||||||||

| Dissection of Lt. common and external iliac vessel | ||||||||||

| Ligation of Lt. internal iliac artery | ||||||||||

| 5 | Tertiary surgery | Laparotomy | Posterior approach of hip | Osteosarcoma | R0 | R0 | 20000 | 52 | 52 | 11.5 |

| Mass excision | Wide excision, neurotomy L5-S1 | |||||||||

| Rectum mobilization | ||||||||||

| 6 | Tertiary surgery | Laparotomy | Ilioinguinal approach | LGFMS | R1 | R0 | 12000 | 67 | 206.8 | 28.9 |

| Mass excision | Marginal excision skin flap and graft | |||||||||

| Int. iliac-deep femoral artery, allograft bypass | ||||||||||

| Rt. D-J catheter insertion with primary bladder repair | ||||||||||

| 6 | Quaternary surgery | Laparotomy | Prone position | Osteosarcoma | R1 | R0 | 700 | 12 | 206.8 | 14.6 |

| Mass excision | Wide excision | |||||||||

| 7 | Primary surgery | Laparoscopy | Posterior approach of hip | Malignant spindle cell tumor | R0 | R0 | 10000 | 69 | 11.4 | 7.5 |

| Mass excision | Wide excision neurolysis L5-S3, Lt. | |||||||||

| Dissection and mobilization of Lt. external and internal iliac vessel | ||||||||||

| 8 | 5th surgery | Laparoscopy | Ilioinguinal approach | Chondrosarcoma | R0 | R0 | 300 | 9 | 115 | 13.7 |

| Mass excision, Rt. PLND | Marginal excision | |||||||||

| Primary closure of Rt. external iliac vein | ||||||||||

Prior to surgery, six patients underwent arterial embolization to reduce blood loss; nevertheless, their estimated median blood loss was 2000 mL (range, 300-20000 mL). Furthermore, nine patients received transfused blood intraoperatively. Ligation of the internal iliac vessel in one patient and dissection with mobilization of the iliac vessel in three were performed by a vascular surgical team. In addition, the vascular surgical team performed an internal iliac artery-deep femoral artery allograft bypass on one patient. The gynecologic oncology team performed another dissection and primary closure of the iliac vessel. These procedures are necessary to achieve surgical margins and reduce blood loss.

The median hospitalization duration was 12.6 d (range: 9-69 d). Reoperation was needed in two patients, one for wound necrosis and the other for bowel perforation and wound necrosis. No postoperative deaths occurred.

All the patients had the total tumor mass removed macroscopically, and four (40%) achieved R0 resection through intra- and extra-pelvic surgical treatment. The most common histology of RPS (two patients) was the myxoid type of well-differentiated liposarcoma. LMS, MPNST, osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma (LGFMS), and malignant spindle cell tumor were also noted. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy was administered to two patients, and all patients received adjuvant treatment (RT and/or chemotherapy).

Five patients are currently alive. Two patients died due to RPS progression, and one was lost to follow-up. Among the five living patients, disease progression was reported in three, while two showed no progression. The median OS was 64.6 mo (range, 11.4-206.8 mo), and the median PFS following treatment was 13.7 mo (range, 4.3-50.6 mo).

RPS consists of a heterogeneous group of malignant tumors with very low incidence. Very little is known about their biological behavior, and no specific causative compounds have been identified[9]. Macroscopically clear margins are an important prognostic factor for patients[9]. However, securing a clear margin is challenging because of the tumor location. Malinka et al[10] reported a macroscopically clear margin in 84% (51, total 61). Hogg et al[11] in a separate study, reported it in 88.9% (80, total 90). Our finding that all patients had a macroscopically clear margin is superior to that of conventional studies.

Patients used all treatment methods currently available, including surgical approaches, chemo

However, the efficacy of chemotherapy and immunotherapy for RPS is limited. The role of adjuvant/neo-adjuvant systemic therapy is not well-defined because of the rarity of the disease and the paucity of randomized controlled data. The role of palliative systemic therapy is better established, mostly through extrapolation of data from sarcomas at other locations[15]. Currently, anthracycline-based therapy is the standard first-line treatment[16]. However, it induces a response in only 15%-35% of patients, irrespective of the histological subtype[17]. Thus, complete surgical resection is considered a milestone in RPS treatment. Several agents have recently emerged as second-line treatment options, including gemcitabine/docetaxel, high-dose ifosfamide monotherapy, trabectedin, pazopanib, and eribulin. According to the PALETTE study, pazopanib significantly increased PFS compared with placebo in metastatic soft tissue sarcoma, progressing despite previous standard chemotherapy[18]. According to Dickson et al[19] the selective CDK4 and CDK6 inhibitor palbociclib inhibits growth and induces senescence in liposarcoma cell lines, favoring progression free; however, there was no significant difference in PFS between patients who had or had not received prior systemic therapy (P = 0.70). Depending on the histological type, there are several randomized controlled trials on neoadjuvant or systemic chemotherapy. The EORTC-1809-STBSG- STRASS 2 study was intended to be an international randomized multicenter, open-label phase 3 trial, with stratification by specific tumor histology, including only high-grade dedifferentiated liposarcoma and LMS[20]. This study aimed to evaluate whether neoadjuvant chemotherapy reduces the development of distant metastases in these well-defined histologic entities[20]. Thus, we are awaiting this result to determine the efficacy of neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Complete surgical resection and securing clear surgical margins are the most effective therapeutic methods. However, as described above, surgical treatment is challenging for most surgeons because of the RPS location. To overcome this obstacle, neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant therapy was developed, and the Trans-Atlantic RPS Working Group was established in 2013. This group insisted on the importance of presurgical imaging studies and multidisciplinary discussions for patients with RPS. They also noted that complete resection should be accomplished despite large resections of adjacent organs[1]. Thus, an interdisciplinary collaboration among teams of surgeons, anesthesiologists, and nurses is necessary to achieve a complete RPS resection.

Several side effects have been noted following a multidisciplinary approach for RPS resection. Although there were no deaths in our sample, reoperation was needed in two patients. One patient underwent wound revision and local flap coverage for wound necrosis 17 d after surgery. The other patient’s complications were more severe (i.e., bowel perforation and wound necrosis), requiring exploratory laparotomy with ileostomy and wound debridement with flap coverage almost one month postoperatively. Compared to pelvic exenteration for recurrent or advanced cervical cancer, which is one of the most challenging surgeries in gynecological cancer, our multidisciplinary two-step approach resulted in higher wound complications than pelvic exenteration (20% vs 4.3%)[21]. The Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Centre, which reviewed conventional surgical resection for RPS, reported a smaller median size of resected mass than this study [15.5cm (range, 1.8-60.0 cm) vs 12.75 cm (range, 6-45.5 cm)][22]. Long hospitalizations (range, 9-69 d) and large estimated blood loss volumes (range, 300-20000 mL) were also found, despite 60% of the patients receiving pre-operative arterial embolization. All 10 patients also required transfused packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, and/or platelets. Moreover, almost 70% of all the patients had this surgery for recurrent diseases. Considering a few treatment options for recurrent RPS, a multidisciplinary approach is an essential option, though the surgical side effects are severe and the size that can be resected is rather small. This approach achieved a clear margin rate of 100%. Thus, it is a superior method to the conventional single-incision approach.

According to Bizzarri et al[23] minimal invasive surgery could be applied to challenging surgery, keeping the same survival outcomes compared to conventional surgery. This two-step approach can also be changed to minimally invasive surgery using a robotic system or other advanced surgical methods. This could decrease the complication rates in patients with RPS using a two-step approach. Furthermore, this complication rate was lower than that found in a combination of RT and surgery, which achieved a similar clear surgical margin rate. In addition, pre-operative vascular assessment (Tinelli’s Score) could be a new option to achieve surgical margins and reduce blood loss[20,24]. We discussed several factors influencing the surgical status before surgery and performed arterial embolization if the cancerous mass was located or invaded the major vessel. However, we did not use this evaluation system pre-operatively. Therefore, we retrospectively analyzed our data using Tinelli’s Score. Among the 10 cases, six (60%) were grade 1 or 2, and two were grade 3. One case each was grade 4 and 5, and a major vessel allograft was performed in the case of grade 5 vessel invasion. Among the four cases with upper grade 3, arterial embolization was performed in 3. However, for these cases that showed a large amount of bleeding even after embolization, if a large amount of bleeding during surgery is suspected, even with a low score, embolization should be considered before surgery. Therefore, checking the vessel invasion grade, performing arterial embolization before surgery, and co-operation with the vascular surgical team could achieve complete tumor resection and reduce blood loss and surgical complications in the next surgery. Finally, applying enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) or a modified ERAS method may reduce hospitalization and postoperative complications.

These findings support the need for a multicenter or randomized controlled study to test the effectiveness of the multidisciplinary approach, despite the Trans-Atlantic RPS Working Group’s current guideline that the multidisciplinary approach is superior for complete tumor resection.

Therapeutic challenges associated with RPS are based on their location and high risk of recurrence. Therefore, a multidisciplinary approach is necessary to improve patient outcomes. The location of RPS and the benefits of using intra- and extra-pelvic treatments make this a good candidate for a multi

Retroperitoneal sarcoma (RPS) is a rare malignancy and is associated with poor prognosis. Although several studies have assessed the survival benefits of wide excision, few have reported detailed methods for achieving wide excision in patients with RPS.

Considering poor prognosis of RPS, we'd like to find effective surgical approach to complete resection for RPS. This Multidisciplinary surgery is an anatomical approach that combines intra- and extra-peritoneal access within the same surgery to achieve complete RPS removal.

We described our experience with multidisciplinary surgical resection of RPS using intra- and extra-pelvic approaches.

This study reviewed of the records of patients who underwent multidisciplinary surgery for RPS analyzed surgical and survival outcomes retrospectively.

All patients’ RPS masses were removed completely, and four achieved R0 resection through intra- and extra-pelvic surgery.

RPS is therapeutically challenging because of its location and high risk of recurrence. Therefore, intra- and extra-pelvic surgical approaches can improve the macroscopic security of the surgical margin.

These findings support the need for a multicenter or randomized controlled study to test the effectiveness of the multidisciplinary approach, despite the Trans-Atlantic RPS Working Group’s current guideline that the multidisciplinary approach is superior for complete tumor resection.

| 1. | Trans-Atlantic RPS Working Group. Management of primary retroperitoneal sarcoma (RPS) in the adult: a consensus approach from the Trans-Atlantic RPS Working Group. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:256-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Tan MC, Brennan MF, Kuk D, Agaram NP, Antonescu CR, Qin LX, Moraco N, Crago AM, Singer S. Histology-based Classification Predicts Pattern of Recurrence and Improves Risk Stratification in Primary Retroperitoneal Sarcoma. Ann Surg. 2016;263:593-600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 271] [Article Influence: 27.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gronchi A, Strauss DC, Miceli R, Bonvalot S, Swallow CJ, Hohenberger P, Van Coevorden F, Rutkowski P, Callegaro D, Hayes AJ, Honoré C, Fairweather M, Cannell A, Jakob J, Haas RL, Szacht M, Fiore M, Casali PG, Pollock RE, Raut CP. Variability in Patterns of Recurrence After Resection of Primary Retroperitoneal Sarcoma (RPS): A Report on 1007 Patients From the Multi-institutional Collaborative RPS Working Group. Ann Surg. 2016;263:1002-1009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 413] [Article Influence: 41.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Trans-Atlantic RPS Working Group. Management of Recurrent Retroperitoneal Sarcoma (RPS) in the Adult: A Consensus Approach from the Trans-Atlantic RPS Working Group. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:3531-3540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | van Houdt WJ, Zaidi S, Messiou C, Thway K, Strauss DC, Jones RL. Treatment of retroperitoneal sarcoma: current standards and new developments. Curr Opin Oncol. 2017;29:260-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Paik ES, Kang JH, Kim J, Lee YJ, Choi CH, Kim TJ, Kim BG, Bae DS, Lee JW. Prognostic factors for recurrence and survival in uterine leiomyosarcoma: Korean single center experience with 50 cases. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2019;62:103-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cananzi FCM, Ruspi L, Sicoli F, Minerva EM, Quagliuolo V. Did outcomes improve in retroperitoneal sarcoma surgery? Surg Oncol. 2019;28:96-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Adam MA, Moris D, Behrens S, Nussbaum DP, Jawitz O, Turner M, Lidsky M, Blazer D 3rd. Hospital Volume Threshold for the Treatment of Retroperitoneal Sarcoma. Anticancer Res. 2019;39:2007-2014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mantas D, Garmpis N, Polychroni D, Garmpi A, Damaskos C, Liakea A, Sypsa G, Kouskos E. Retroperitoneal sarcomas: from diagnosis to treatment. Case series and review of the literature. G Chir. 2020;41:18-33. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Malinka T, Nebrig M, Klein F, Pratschke J, Bahra M, Andreou A. Analysis of outcomes and predictors of long-term survival following resection for retroperitoneal sarcoma. BMC Surg. 2019;19:61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hogg HD, Manas DM, Lee D, Dildey P, Scott J, Lunec J, French JJ. Surgical outcome and patterns of recurrence for retroperitoneal sarcoma at a single centre. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2016;98:192-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Haas RLM, Bonvalot S, Miceli R, Strauss DC, Swallow CJ, Hohenberger P, van Coevorden F, Rutkowski P, Callegaro D, Hayes AJ, Honoré C, Fairweather M, Gladdy R, Jakob J, Szacht M, Fiore M, Chung PW, van Houdt WJ, Raut CP, Gronchi A. Radiotherapy for retroperitoneal liposarcoma: A report from the Transatlantic Retroperitoneal Sarcoma Working Group. Cancer. 2019;125:1290-1300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Turner BT, Hampton L, Schiller D, Mack LA, Robertson-More C, Li H, Quan ML, Bouchard-Fortier A. Neoadjuvant radiotherapy followed by surgery compared with surgery alone in the treatment of retroperitoneal sarcoma: a population-based comparison. Curr Oncol. 2019;26:e766-e772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Roeder F, Ulrich A, Habl G, Uhl M, Saleh-Ebrahimi L, Huber PE, Schulz-Ertner D, Nikoghosyan AV, Alldinger I, Krempien R, Mechtersheimer G, Hensley FW, Debus J, Bischof M. Clinical phase I/II trial to investigate preoperative dose-escalated intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) and intraoperative radiation therapy (IORT) in patients with retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcoma: interim analysis. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Constantinidou A, Jones RL. Systemic therapy in retroperitoneal sarcoma management. J Surg Oncol. 2018;117:87-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | van Houdt WJ, Raut CP, Bonvalot S, Swallow CJ, Haas R, Gronchi A. New research strategies in retroperitoneal sarcoma. The case of TARPSWG, STRASS and RESAR: making progress through collaboration. Curr Opin Oncol. 2019;31:310-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Almond LM, Gronchi A, Strauss D, Jafri M, Ford S, Desai A. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant strategies in retroperitoneal sarcoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44:571-579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | van der Graaf WT, Blay JY, Chawla SP, Kim DW, Bui-Nguyen B, Casali PG, Schöffski P, Aglietta M, Staddon AP, Beppu Y, Le Cesne A, Gelderblom H, Judson IR, Araki N, Ouali M, Marreaud S, Hodge R, Dewji MR, Coens C, Demetri GD, Fletcher CD, Dei Tos AP, Hohenberger P; EORTC Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group; PALETTE study group. Pazopanib for metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma (PALETTE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2012;379:1879-1886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1455] [Cited by in RCA: 1615] [Article Influence: 115.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Dickson MA, Schwartz GK, Keohan ML, D'Angelo SP, Gounder MM, Chi P, Antonescu CR, Landa J, Qin LX, Crago AM, Singer S, Koff A, Tap WD. Progression-free survival among patients with well-differentiated or dedifferentiated liposarcoma treated with cdk4 inhibitor palbociclib: A phase 2 clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:937-940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 260] [Article Influence: 28.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Trans-Atlantic Retroperitoneal Sarcoma Working Group (TARPSWG). Management of metastatic retroperitoneal sarcoma: a consensus approach from the Trans-Atlantic Retroperitoneal Sarcoma Working Group (TARPSWG). Ann Oncol. 2018;29:857-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ter Glane L, Hegele A, Wagner U, Boekhoff J. Pelvic exenteration for recurrent or advanced gynecologic malignancies - Analysis of outcome and complications. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2021;36:100757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Fairweather M, Wang J, Jo VY, Baldini EH, Bertagnolli MM, Raut CP. Surgical Management of Primary Retroperitoneal Sarcomas: Rationale for Selective Organ Resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25:98-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bizzarri N, Chiantera V, Ercoli A, Fagotti A, Tortorella L, Conte C, Cappuccio S, Di Donna MC, Gallotta V, Scambia G, Vizzielli G. Minimally Invasive Pelvic Exenteration for Gynecologic Malignancies: A Multi-Institutional Case Series and Review of the Literature. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:1316-1326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Vizzielli G, Chiantera V, Tinelli G, Fagotti A, Gallotta V, Di Giorgio A, Gueli Alletti S, Scambia G. Out-of-the-box pelvic surgery including iliopsoas resection for recurrent gynecological malignancies: Does that make sense? Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43:710-716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: D'Orazi V, Italy; Lu H, China S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: A P-Editor: Gong ZM