Published online Aug 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i24.8788

Peer-review started: April 12, 2022

First decision: May 12, 2022

Revised: May 31, 2022

Accepted: July 22, 2022

Article in press: July 22, 2022

Published online: August 26, 2022

Processing time: 125 Days and 21.7 Hours

Type two autoimmune pancreatitis is a rare and difficult to diagnose, steroid responsive non-IgG4 inflammatory pancreatopathy that can be associated with inflammatory bowel disease.

This case series describes three cases with varied clinical presentations and re-presentations of autoimmune pancreatitis, and all associated with an aggressive course of ulcerative colitis. The pancreatopathy was independent of bowel disease activity and developed in one case following colectomy.

Clinician awareness about this condition is important to allow early diagnosis, treatment and avoid unnecessary pancreatic surgery.

Core Tip: Type two autoimmune pancreatitis is a rare and difficult to diagnose, steroid responsive non-IgG4 inflammatory pancreatopathy that can be associated with an aggressive course of ulcerative colitis but with independence from bowel disease activity. Clinician awareness about this condition is important to allow early diagnosis, treatment and avoid unnecessary pancreatic surgery.

- Citation: Ghali M, Bensted K, Williams DB, Ghaly S. Type 2 autoimmune pancreatitis associated with severe ulcerative colitis: Three case reports. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(24): 8788-8796

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i24/8788.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i24.8788

The inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis (UC), are multisystem diseases that cause chronic relapsing inflammation within the gastrointestinal tract, and are associated with extraintestinal manifestations in up to 50% of patients[1]. Autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) is one of the less recognised associations and remains poorly understood. AIP is a rare, fibro-inflammatory disease characterized by well-defined histopathological changes with an unclear pathogenesis[2]. The annual incidence rate has been reported between 0.29 to 1.4 per 100000 population, with a prevalence rate up to 4.6 per 100000 population[3,4]. Two distinct types have been described: Type one AIP (lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis), which is considered the pancreatic manifestation of IgG4-related disease, and type two AIP (idiopathic duct centric pancreatitis) which has been associated with inflammatory bowel disease[5].

The diagnosis of type 2 AIP is based on the International Consensus Diagnostic Criteria (ICDC), which combines clinical, imaging and histological findings (Table 1). The criteria acknowledge the level of uncertainty in diagnosing type 2 AIP by having criteria for definitive and probable diagnoses, these are summarized in Table 2. Of relevance the diagnostic requirements in patients with a clinical diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease are less stringent. Probable type 2 AIP requires level 1 or 2 imaging evidence and a response to steroids; definitive type 2 AIP requires level 1 or 2 imaging evidence and level 1 or 2 histology and a response to steroids[6]. In clinical practice, acquiring adequate tissue by endoscopic ultrasound guided biopsy of the pancreas is difficult, particularly given granulocytic epithelial lesions can have a patchy distribution[7]. Distinguishing AIP from other malignant and non-malignant diagnoses is essential given the marked differences in prognosis and treatment.

| Level 1 | Level 2 | |

| Clinical | A response to a steroid trial with rapid (< 2 wk) radiologically demonstrable resolution or marked improvement in manifestations | Clinically diagnosed inflammatory bowel diseases |

| Parenchymal imaging | Diffuse enlargement with delayed enhancement | Segmental/focal enlargement with delayed enhancement |

| Ductal imaging | Long (> 1/3 length of the main pancreatic duct) or multiple strictures without marked upstream dilatation | Segmental/focal narrowing without marked upstream dilatation (duct size, < 5 mm) |

| Histology | Granulocytic infiltration of duct wall, granulocytic epithelial lesions with or without granulocytic acinar inflammation and; absent or scant (0-10 cells/HPF) IgG4-positive cells | Granulocytic and lymphoplasmacytic acinar infiltrate and; again absent or scant (0-10 cells/HPF) IgG4-positive cells |

| Imaging evidence | Collateral evidence | |

| Probable | Level 1 or 2 | Level 2 histology OR; IBD and response to steroids |

| Definitive | Level 1 or 2 | Level 1 histology OR; IBD, level 2 histology and response to steroids |

Here we present three cases of patients with UC presenting with severe pancreatopathies from a single centre tertiary hospital IBD unit. Each case demonstrated unique clinical features, however were similar in their severe course of IBD. A summary of the cases has been included in Table 3.

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | |

| Gender | Male | Male | Female |

| Age at IBD diagnosis | 54 | 56 | 46 |

| Extent of UC (Montreal) | A3 E3 | A3 E3 | A3 E3 |

| Extraintestinal manifestations | Recurrent mouth ulceration | Nil | Nil |

| Surgery | Colectomy | Colectomy | Nil |

| Occurrence of cancers | Nil | Nil | Nil |

| Age at AIP diagnosis | 55 | 62 | 46 |

| AIP type | Probable type 2 | Probable type 2 | Definitive type 2 |

| Other organ involvement | Nil | Nil | Nil |

| Presentation | Obstructive jaundice | Obstructive jaundice | Acute pancreatitis |

| IBD or AIP first | IBD | IBD | IBD |

| Treatment | Corticosteroids | Corticosteroids | Corticosteroids |

| Relapse | Yes (spontaneous resolution) | Nil | Yes (treated with corticosteroids) |

| Evolution (diabetes, exocrine insufficiency) | Diabetes | Diabetes, Exocrine insufficiency | Nil |

Case 1: A 57-year-old man presented with the onset of scleral icterus and jaundice over a 3-day period.

Case 2: A 62-year-old man presented with jaundice.

Case 3: A 46-year-old female presented with epigastric pain.

Case 1: The patient had one month of lethargy preceding his acute presentation with jaundice.

Case 2: The patient’s jaundice was associated with epigastric pain and 8 kg weight loss.

Case 3: The patient had mild distal UC diagnosed one month earlier treated with mesalazine suppositories.

Case 1: Past medical history included a non-significant alcohol history and UC diagnosed 3 years earlier and requiring subtotal colectomy with ileostomy soon after diagnosis due to acute severe colitis failing rescue therapy. Following surgery the patient was off all medical therapy.

Case 2: Past medical history included a non-significant alcohol history, prior cholecystectomy and long-standing ulcerative pancolitis in clinical remission without ongoing medical therapy.

Case 3: Past medical history included no significant alcohol history, iron deficiency anaemia, HSV type 2 infection, and recurrent pneumothoraces requiring pleurodesis and pleurectomy.

Case 1: Bloods demonstrated a mixed pattern of liver function test derangements: Bilirubin 64 μmol/L (0-18), ALT 1200 U/L (0-30), AST 458 U/L (0-30), ALP 999 U/L (30-100), GGT 2180 U/L (0-35) with bilirubin soon peaking at 151 μmol/L. A random blood sugar level was elevated to 15 mmol/L (4.0-7.8) with no history of diabetes. HbA1c was 7.0% (0-5.9). Serum CA 19.9 47kU/L (0-34 kU/L) and IgG4 0.58g/L (0.04-1.64g/L).

Case 2: Blood tests demonstrated bilirubin 200 μmol/L (4-20), AST 118 U/L (10-40), ALT 284 U/L (5-40), ALP 169 U/L (35-110), GGT 792 U/L (5-50), and hyperglycaemia with BGL 14 mmol/L (4.0-7.8) with no prior history of diabetes. Serum CA 19.9 was non-specifically elevated 62 kU/L (< 40), triglycerides normal 2.1 mmol/L (0.5-2) and IgG4 Levels were normal 0.69 g/L (0.04-1.64). Subsequent CA 19.9 were 51 and 15 kU/L, 3 wk and 2 mo later, respectively.

Case 3: Bloods showed an elevated lipase 518 U/L (8-78). Serum triglycerides 0.7 mmol/L (< 2.0) and IgG4 were not elevated 0.38 g/L (0.04-0.86).

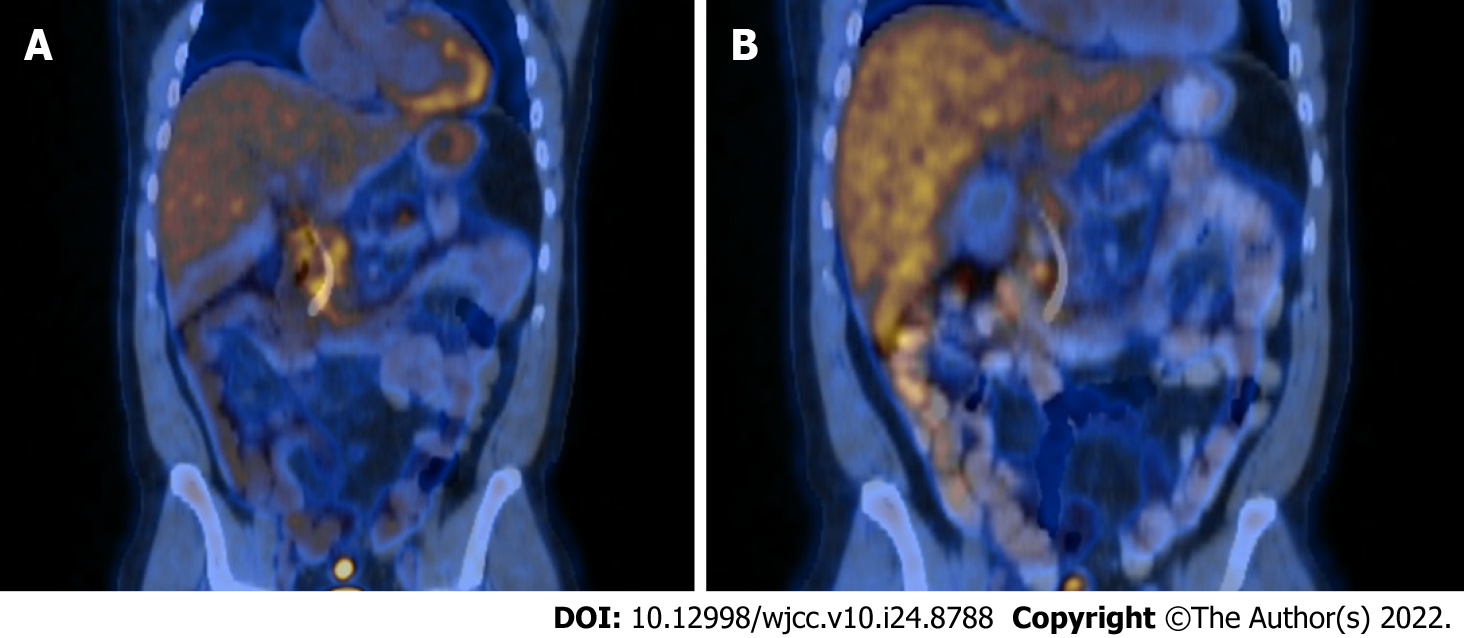

Case 1: Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) demonstrated intra and extrahepatic bile duct dilatation with a transition point at the distal common bile duct, although no pancreatic mass was identified. No supporting features of primary sclerosing cholangitis. There was diffuse diffusion restriction involving the pancreatic head, neck and proximal body, suspicious for autoimmune pancreatitis. Findings on contrast enhanced endoscopic ultrasound (CE-EUS) and fludeoxy glucose-positron emission tomography/CT (FDG-PET/CT), were also consistent with this – with diffusely increased tracer activity within the pancreas suggestive of an inflammatory process rather than malignancy (Figure 1A), and diffusely abnormal pancreas on CE-EUS with heterogeneous honeycombed appearance, and atrophy of the pancreatic tail.

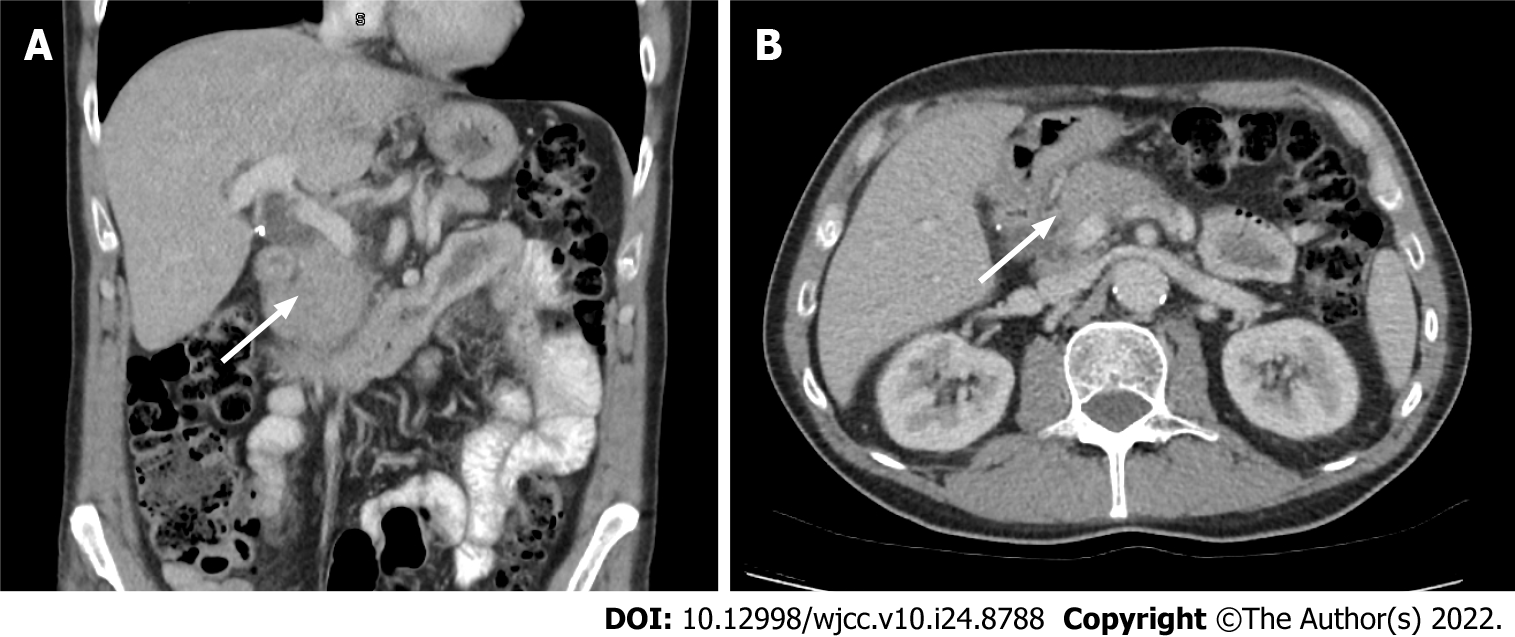

Case 2: Multiphasic CT abdomen and MRCP demonstrated mild thickening and oedema of the head and body of the pancreas with subtle effacement of the peri-pancreatic fat planes, with associated intra and extrahepatic biliary dilatation with a common bile duct of 9 mm and abrupt cut off within the pancreatic head, raising concern of malignancy (Figures 2 and 3). CE-EUS however demonstrated a diffusely hypoechoic pancreas with no distinct mass lesion. The pancreas was uniformly hypervascular with no discrete area of altered microvascular flow in the head of the pancreas.

Case 3: Abdominal ultrasound excluded cholelithiasis. CT abdomen showed features of mild pancreatitis. MRCP demonstrated changes of pancreatitis with mild oedema of the tail of pancreas associated with minimal peripancreatic stranding, but no mass or cystic lesions of the pancreas.

Considering the remote possibility of mesalazine suppositories causing pancreatitis, this was switched to prednisolone suppositories. Despite this, over the subsequent months the patient experienced ongoing pain, reduced appetite, weight loss and ultimately required hospitalization. FDG-PET/CT revealed mild to moderate avidity in the whole pancreas.

Probable type 2 autoimmune pancreatitis associated with severe ulcerative colitis was the diagnosis in each case at this point. However, with case three, a definitive diagnosis was made following further investigation as will be discussed below.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) demonstrated a tight 3.5 cm distal biliary stricture, with non-diagnostic bile brushings and a plastic stent was inserted for biliary drainage. Duodenal biopsy revealed duodenitis with 3 IgG4 positive plasma cells per high power field with an IgG4:IgG of 5% (fewer than the > 10 required to diagnose IgG4 disease). Based on multimodal imaging and EUS findings, a diagnosis of probable type 2 AIP was considered, and treatment commenced with prednisolone 40mg tapered over eight weeks.

ERCP demonstrated a 2 cm smooth stricture in the distal CBD with a dilated proximal duct of 9 mm, no additional intra- or extrahepatic biliary strictures were noted to suggest primary sclerosing cholangitis which was deemed unlikely given the diffuse pancreatic changes on imaging. Bile duct brushing were taken and demonstrated benign biliary epithelium. A 7 cm plastic biliary stent was placed. To confirm the benign nature of the biliary stricture, balloon cholangioscopy was subsequently performed and a fully covered self-expanding metal stent (SEMS) was inserted. This was able to be successfully removed 6 mo later. Based on CE-EUS and imaging findings, a diagnosis of probable type two AIP was considered and a steroid trial commenced with prednisone 30 mg daily tapered over 8 wk, pancreatic enzyme supplementation for pancreatic insufficiency, and supplemental insulin for new-onset diabetes. There was no recurrence of pancreatitis or jaundice after completing the steroid taper.

Based on the above investigations type 2 AIP was considered probable and a tapering trial of prednisone 40 mg over 8 wk commenced.

A repeat FDG-PET/CT following steroid treatment demonstrated complete resolution of FDG uptake (Figure 1B). The benign stricture required sequential plastic stenting, which were subsequently removed after six months. Eighteen months later, the patient developed acute pancreatitis presenting with epigastric abdominal pain, elevated CRP (174 mcg/mL) and lipase (360 U/L), which resolved with conservative measures. CT and ultrasound showed features of pancreatitis but excluded cholelithiasis and there was no biliary dilatation. The patient went on to have completion proctectomy which was uncomplicated and has remained well 24 mo after this episode with no further pancreatitis or need for immunosuppression.

Three months after the initial episode of jaundice, the patient experienced an episode of acute severe ulcerative colitis requiring IV hydrocortisone and rescue therapy with infliximab. He remained in clinical remission for 6 mo on combination therapy with infliximab, azathioprine and allopurinol but subsequently had secondary loss of response to dose optimized infliximab, vedolizumab and tofacitinib. He ultimately came to colectomy three years after his pancreatitis diagnosis. There was no recurrence of pancreatitis subsequently.

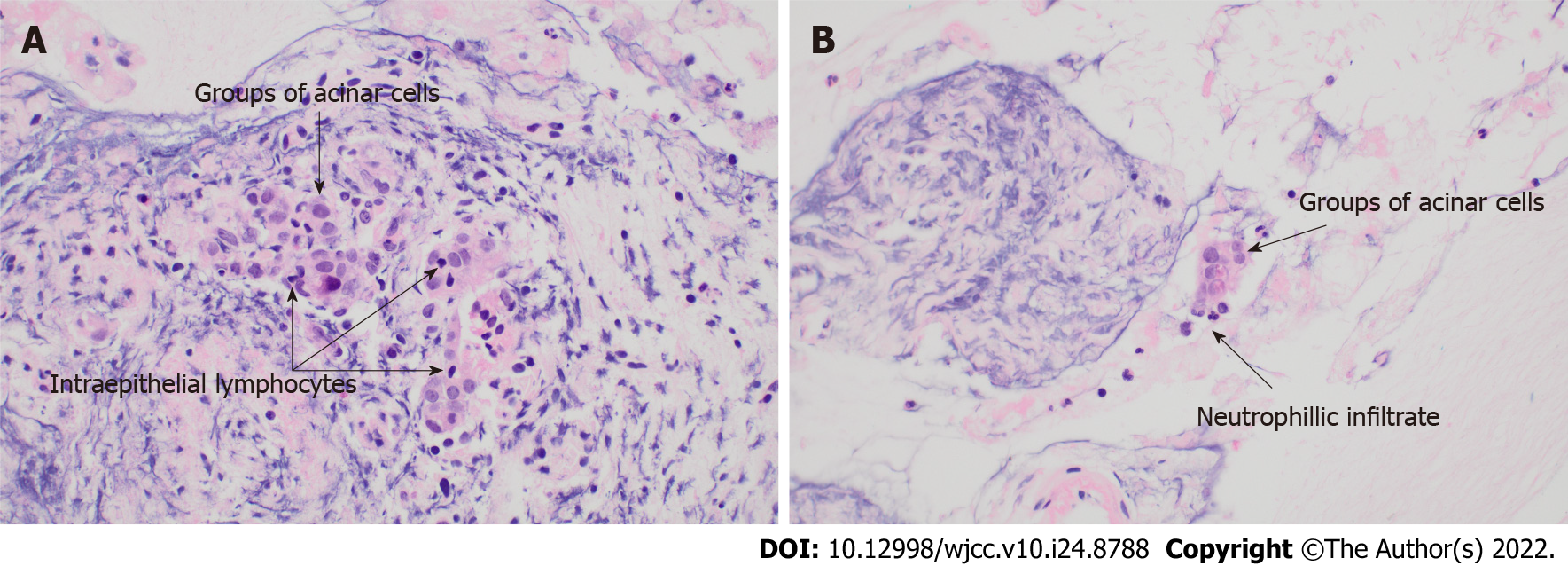

Symptoms ultimately improved slowly over the subsequent month, however relapsed once a prednisolone dose of 15 mg was reached. Repeat FDG-PET/CT revealed improvement in the degree of FDG uptake but ongoing activity in the pancreatic head and uncinate process. CE-EUS with fine needle biopsy was performed. This showed abnormal pancreatic parenchyma that was honeycombed and lobular in the head and neck of the pancreas. Within the uncinate there was a 17 mm focal hypoechoic area that was targeted for fine needle biopsy. The histopathology demonstrated lymphocytic acinar inflammation and features suggestive of granulocytic acinar infiltrate, which could be consistent with type 2 AIP (Figure 3). There were no pancreatic ducts present in the specimen, therefore duct centric inflammation or the presence of granulocytic epithelial lesions could not be assessed. No plasma cells were seen, and thus the tissue was presumably absent of IgG4-positive cells. Symptoms were managed with regular analgesia and pancreatic enzyme replacement due to the patients’ reluctance for further steroid therapy.

Three months later, the patient developed acute severe UC with disease extension to the descending colon. She was treated with intravenous hydrocortisone, and subsequently rescue therapy with infliximab followed by ciclosporin after declining colectomy and a lack of response to infliximab. A partial response to ciclosporin was observed and allowed transition to vedolizumab with improvement in symptoms. She has remained in clinical remission with 12 mo of follow up with no relapse of pancreatitis or ulcerative colitis on maintenance vedolizumab 4-weekly infusions.

The presentation of AIP in the setting of IBD is variable with one study showing 80% presenting with acute pancreatitis, 11% with abdominal pain, 7% with jaundice and 2% being incidentally detected. Of note in the GETAID-AIP study, 98% of those with IBD and AIP, had type 2 AIP illustrating the relationship with IBD being more specific to type 2 AIP[8]. Our case series demonstrated the varied clinical presentations of AIP, with obstructive jaundice in two, and acute pancreatitis in one. Of interest, patients did not necessarily relapse with the same clinical presentation, with case one initially presenting with jaundice and subsequently presenting with abdominal pain.

Autoimmune pancreatitis in the setting of IBD is challenging to diagnose but a clinically important entity to recognize and treat accordingly. The cases presented highlight a unique phenotype of both severe pancreatopathy and severe IBD. Despite this, they do not easily fit the published diagnostic criteria of AIP despite multiple diagnostic investigations. This is consistent with findings from the GETAID case series where only 16% of IBD associated pancreatitis met definitive type 2 AIP criteria[8]. In our cases, 2 met the criteria for probable type 2 AIP based on imaging findings (level 1 or 2), clinical diagnosis of IBD and response to steroids. The third case met criteria for definitive type 2 AIP based on supportive imaging findings (level 2), level 2 histology with clinical IBD and response to steroids. It is important to note the diagnostic criteria for response to steroids is based on either radiologically demonstrable resolution or marked improvement in manifestations within 2 wk, with radiological confirmation likely to be more useful in the context of uncertainty regarding potential malignancy[6]. Due to several reasons, response to steroids was not assessed after 2 wk by repeat imaging in these cases: firstly, there was thorough initial multimodal evaluation to exclude malignancy; secondly, improvement in jaundice, pain or liver enzymes were consistent with steroid response and; lastly, there were practical challenges regarding access to care for two out of three patients who lived in rural areas > 500 km from the treating centre.

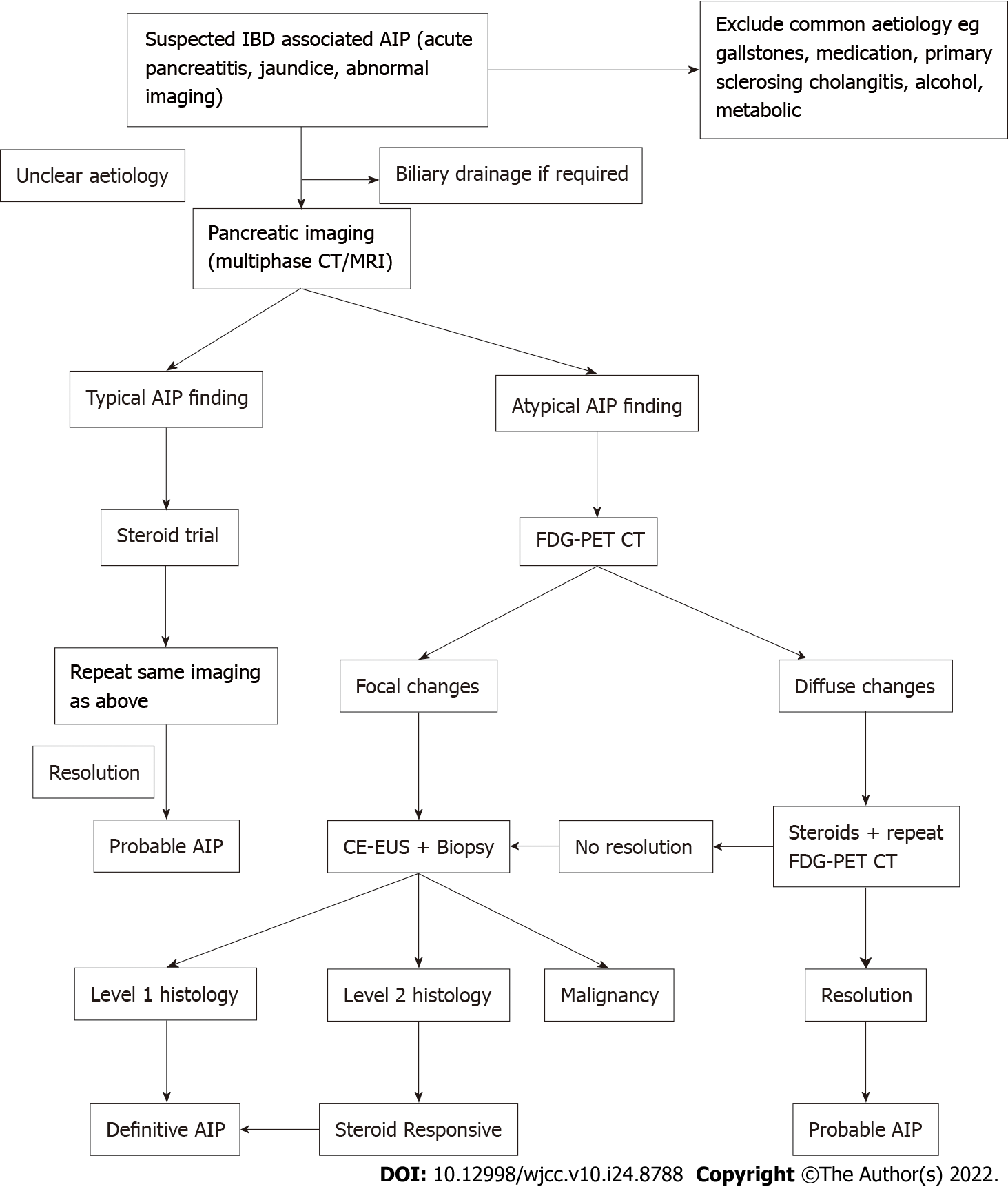

There are no published guidelines for investigating suspected autoimmune pancreatitis in the setting of IBD, which is relevant as the pre-test probability for a positive diagnosis is likely to be higher than the general population. The ICDC for type 2 AIP, emphasise the need for pancreatic core biopsy early in the course of investigation, but this may not be the case in the setting of IBD[6]. In the presented cases FDG-PET/CT and CE-EUS were included in the diagnostic evaluation. A diagnostic steroid trial is suggested to determine if there is rapid radiologically demonstrable resolution or marked improvement in pancreatic/extrapancreatic manifestations[6]. While steroid response does not differentiate type 1 from type 2 AIP, it is supportive evidence of a form of AIP. An incomplete clinical response to steroids or relapse on a weaning dose, however, may incorrectly steer the diagnosis away from AIP or alternatively a trial of steroids may delay the diagnosis of malignancy. As such, a two weeks trial of steroids followed by assessing the response has been suggested in carefully selected patients[2]. This is highlighted in case three, where the clinical improvement on the initial course of prednisone was short lived, however FDG-PET/CT demonstrated diffuse uptake throughout the pancreas at baseline with definite improvement post steroids. Diffuse uptake of FDG in the pancreas and the ratio of pancreatic lesion/liver, salivary gland and prostate standardized uptake values (SUV) thresholds have been suggested by others to favor but not definitively diagnose AIP[9]. Caution needs to be taken with focal compared to diffuse abnormalities that improve with corticosteroids, as this can also be seen with malignancy.

In cases where there is a focal pancreatic lesion, use of CE-EUS may help distinguish AIP from pancreatic cancer and justify a trial of steroids. On CE-EUS, AIP demonstrates hyper to iso enhancement in the arterial phase, homogenous contrast agent distribution and absent irregular internal vessels[10]. Thus, CE-EUS can be used to aid the diagnosis of AIP by decreasing the likelihood of a cancer diagnosis whilst justifying the use of a steroid trial. EUS also offers the opportunity for pancreatic biopsy at the same procedure. The utility of histological acquisition in diagnosis was demonstrated in case three where biopsy excluded malignancy and demonstrated changes suggestive of type 2 AIP[11]. Therefore, considering our cases and the modalities of FDG-PET/CT and CE-EUS, one possible strategy could include performing FDG-PET/CT scans, followed by CE-EUS with or without biopsy depending on clinical suspicion, to determine utility of a trial of steroids. We have incorporated this into a suggested diagnostic algorithm shown in Figure 4. The diagnostic accuracy and cost-effectiveness of this strategy requires investigation.

The presence of autoimmune pancreatitis in UC may indicate a more severe phenotype of IBD. This is supported by the largest case series looking at AIP and UC by the GETAID-AIP study group, with a statistically significant increase in colectomy rate in patients with IBD and AIP compared to those that had IBD without AIP[8]. In two of our three cases, the patients required colectomy. This suggests a unique phenotype of IBD patients with genetic predisposition to AIP and aggressive IBD. In the GETAID-AIP study, of the 18 patients who underwent a colectomy, seven had a colectomy prior to a diagnosis of AIP. This can be seen in case one of our series, where the diagnosis of AIP occurred after their colectomy. In case two, the patient’s colitis was quiescent until the diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis. However, once the patient developed AIP, he had a deterioration in the severity of his IBD, and ultimately required a colectomy. These findings suggest that it is not necessarily active IBD or the colonic microbiome causing the autoimmune pancreatitis, rather it may be genetic, immunological or systemic inflammatory mechanisms causing the disease, with further research required into its pathogenesis.

Autoimmune pancreatitis in the setting of IBD, is a rare and difficult to diagnose, steroid responsive non-IgG4 inflammatory pancreatopathy that does not easily fit the current diagnostic criteria for type 1 or 2 autoimmune pancreatitis and likely represents a separate entity. This case series describes three cases with varied clinical presentations and re-presentations of autoimmune pancreatitis, and all associated with an aggressive course of inflammatory bowel disease. Novel diagnostic tools such as FDG-PET and contrast enhanced EUS may play a role in the evaluation of this condition. Clinician awareness about this condition is important to allow early diagnosis and appropriate therapy.

Histology images courtesy of: Dr Sharron Liang, Postgraduate Molecular Fellow – Anatomical Patho

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Australia

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Innocenti T, Italy; Li HY, China S-Editor: Wang DM L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang DM

| 1. | Vavricka SR, Schoepfer A, Scharl M, Lakatos PL, Navarini A, Rogler G. Extraintestinal Manifestations of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:1982-1992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 546] [Cited by in RCA: 497] [Article Influence: 45.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ketwaroo GA, Sheth S. Autoimmune Pancreatitis. Gastroenterol Rep. 2013;1:27-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Schneider A, Michaely H, Weiss C, Hirth M, Rückert F, Wilhelm TJ, Schönberg S, Marx A, Singer MV, Löhr JM, Ebert MP, Pfützer RH. Prevalence and Incidence of Autoimmune Pancreatitis in the Population Living in the Southwest of Germany. Digestion. 2017;96:187-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kamisawa T, Shimosegawa T. Epidemiology of Autoimmune Pancreatitis. In: The Pancreas. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2018: 503–509. |

| 5. | Ramos LR, Sachar DB, DiMaio CJ, Colombel JF, Torres J. Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Pancreatitis: A Review. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:95-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Shimosegawa T, Chari ST, Frulloni L, Kamisawa T, Kawa S, Mino-Kenudson M, Kim MH, Klöppel G, Lerch MM, Löhr M, Notohara K, Okazaki K, Schneider A, Zhang L; International Association of Pancreatology. International consensus diagnostic criteria for autoimmune pancreatitis: guidelines of the International Association of Pancreatology. Pancreas. 2011;40:352-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1050] [Cited by in RCA: 1082] [Article Influence: 72.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ku Y, Hong SM, Fujikura K, Kim SJ, Akita M, Abe-Suzuki S, Shiomi H, Masuda A, Itoh T, Azuma T, Kim MH, Zen Y. IL-8 Expression in Granulocytic Epithelial Lesions of Idiopathic Duct-centric Pancreatitis (Type 2 Autoimmune Pancreatitis). Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:1129-1138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lorenzo D, Maire F, Stefanescu C, Gornet JM, Seksik P, Serrero M, Bournet B, Marteau P, Amiot A, Laharie D, Trang C, Coffin B, Bellaiche G, Cadiot G, Reenaers C, Racine A, Viennot S, Pauwels A, Bouguen G, Savoye G, Pelletier AL, Pineton de Chambrun G, Lahmek P, Nahon S, Abitbol V; GETAID-AIP study group. Features of Autoimmune Pancreatitis Associated With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:59-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Zhang J, Jia G, Zuo C, Jia N, Wang H. 18F- FDG PET/CT helps differentiate autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreatic cancer. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cho MK, Moon SH, Song TJ, Kim RE, Oh DW, Park DH, Lee SS, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH. Contrast-Enhanced Endoscopic Ultrasound for Differentially Diagnosing Autoimmune Pancreatitis and Pancreatic Cancer. Gut Liver. 2018;12:591-596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cheng MF, Guo YL, Yen RF, Chen YC, Ko CL, Tien YW, Liao WC, Liu CJ, Wu YW, Wang HP. Clinical Utility of FDG PET/CT in Patients with Autoimmune Pancreatitis: a Case-Control Study. Sci Rep. 2018;8:3651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |