Published online Aug 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i24.8775

Peer-review started: April 5, 2022

First decision: June 16, 2022

Revised: June 16, 2022

Accepted: July 22, 2022

Article in press: July 22, 2022

Published online: August 26, 2022

Processing time: 132 Days and 21.3 Hours

Chylothorax is an uncommon condition in which chyle leaks into the pleural cavity, and biliary peritonitis is a rare complication of thoracic duct embolization in clinical practice.

We describe the case of a 50-year-old woman who presented with chylothorax and underwent thoracic duct embolization using a coil and a mixture of histoacryl glue and lipiodol. The patient developed upper abdominal pain and fever after the intervention. She was diagnosed with biliary peritonitis and treated with cholecystectomy at Hanoi Medical University Hospital.

Although thoracic duct embolization is considered a safe and minimally invasive procedure, it is not without risk. Following thoracic duct embolization, severe or persistent abdominal pain should be explored utilizing imaging data and laboratory results to determine problems as soon as possible.

Core Tip: Chylothorax is a condition in which chyle leaks into the pleural cavity. Trauma, spontaneous (non-traumatic), and idiopathic etiologies are all potential causes of chylothorax. In clinical practice, biliary peritonitis is an uncommon consequence of thoracic duct embolization. Despite its reputation as a safe and minimally intrusive technique, thoracic duct embolization is not without hazard. Severe or chronic abdominal discomfort should be investigated as soon as possible after thoracic duct embolization, using imaging data and laboratory results to identify issues.

- Citation: Dung LV, Hien MM, Tra My TT, Luu DT, Linh LT, Duc NM. Cholecystitis-an uncommon complication following thoracic duct embolization for chylothorax: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(24): 8775-8781

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i24/8775.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i24.8775

Chylothorax is a rare disease characterized by chyle leakage into the pleural cavity. The etiology of chylothorax can be traumatic, idiopathic, and non-traumatic including malignancies, primary lymphatic disorders or congenital malformations[1]. Conservative management consisting of dietary control and drainage is typically the first-line treatment. Interventional radiology and surgery are considered if conservative management fails[1]. Thoracic duct embolization is a new, safe, and effective method for chylothorax treatment, it is associated with minimal complications[2,3], and these attributes have contributed to the recent increase in the use of thoracic duct embolization as a first-line treatment for chylothorax[4]. In this case report, we describe the occurrence of biliary peritonitis following thoracic duct embolization for the treatment of chylothorax due to penetration of a percutaneous interventional needle into the gallbladder wall.

A 50-year-old woman presented at Hanoi Medical University Hospital. with dyspnea and chest pain.

The symptoms started 1 mo prior to presentation, with chest discomfort.

Medical records were normal.

There was no personal and family history of other diseases.

Physical examination was not special. On auscultation, vesicular breath sound was diminished with decreased vocal resonance especially at the middle and lower lobes of the right lung.

Blood tests at presentation were in the normal range. Her pleural fluid analysis showed: Triglyceride 20.3 mmol/L and cholesterol 2.2 nmol/L.

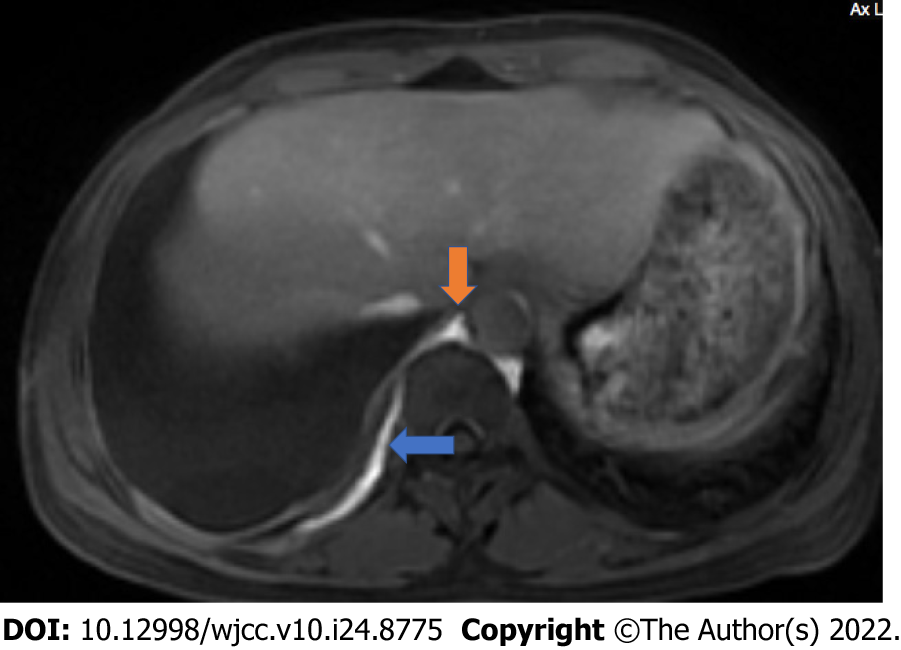

Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance (MR) lymphangiography was performed to obtain coronal and axial T1-weighted and T1-weighted fat-saturated post-gadolinium images, which showed a large right pleural effusion and contrast agent leakage from the right-sided branch of the lower-third of the thoracic duct into the right pleural space (Figure 1) and a double thoracic duct variant.

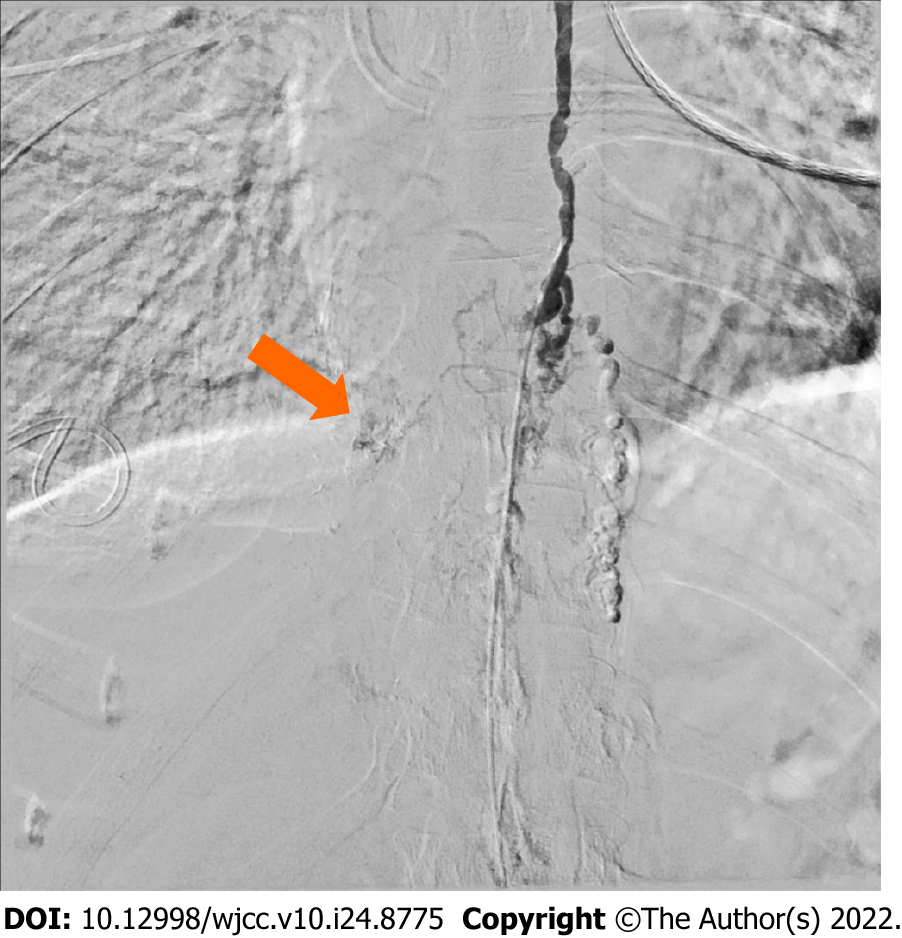

A multidisciplinary consultation (involving respirologists, interventional radiologists, nutritionist) was performed. Three days after presentation, the patient underwent an intranodal lymphangiogram using digital subtraction angiography (DSA), which revealed dilated lymphatic vessels and lymphatic malformations in the lower-third of the thoracic duct, resulting in the leakage of contrast agent into the right pleural space (Figure 2). The patient also had a double lower thoracic duct variant. As the leakage was clear on MR lymphangiography and the patient had a large right pleural effusion (Figure 1), we decided to treatment her with lymphatic embolization, combined with lipid fasting. Under DSA guidance, the cisterna chyli was accessed percutaneously through the anterior abdominal wall with a 22-gauge Chiba needle. A right transabdominal approach was performed to avoid the aorta. The contrast was injected to confirm appropriate placement in the cisterna chyli. A wire was then advanced through the needle and placed within the thoracic duct. The thoracic duct below the leak was embolized under DSA, using a coil and a mixture of histoacryl glue and lipiodol.

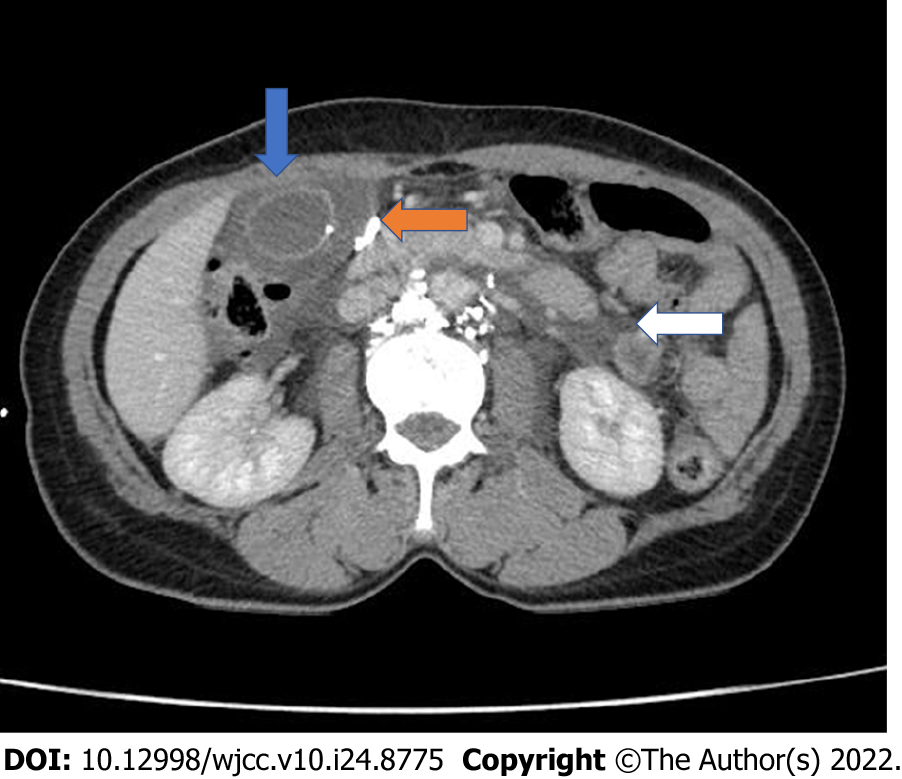

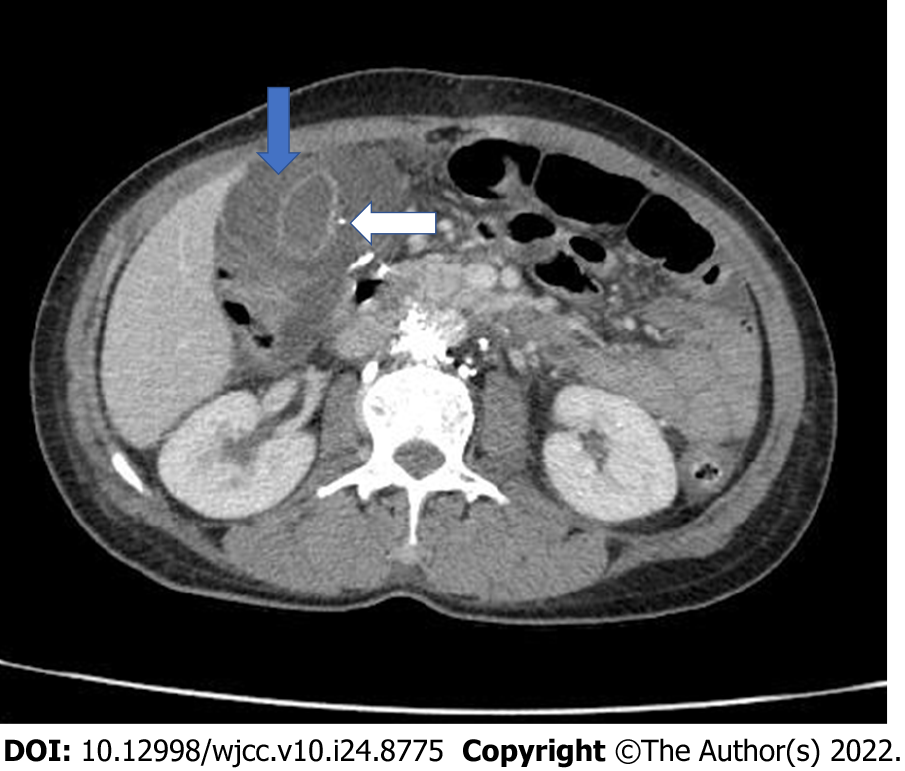

Several hours after this intervention, the patient reported moderate–severe epigastric and right quadrant pain. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) was immediately performed, which showed wall thickening and subserosal edema in the gallbladder (Figure 3), with peripancreatic fluid extending into the pararenal spaces and bilateral paracolic gutters. The pancreas was homogeneously enhanced, with no signs of necrosis or pancreatic duct dilatation. A small, high-density nodule was observed in the gallbladder wall. The initial diagnosis was acute pancreatitis after lymphatic intervention; thus, she underwent conservative treatment instead of surgery. The respiratory symptoms were resolved by the intervention, but the patient experienced increasing abdominal pain and mild fever. Blood tests revealed an infectious condition: white blood cell count (WBC), 13.5 G/L; neutrophils, 88.7%; and C-reactive protein (CRP), 3.49 mg/dL. Pancreatic enzymes were within the normal range: amylase, 84 U/L; lipase, 20 U/L; and total/direct bilirubin, 9.6/5.7 µmol/L. A second contrast-enhanced abdominal CT performed 3 days later revealed further gallbladder wall thickening (approximately 20 mm) and subserosal edema (Figure 4), with no signs of stones, pseudoaneurysm, or contrast agent leakage. The small, high-density nodule on the gallbladder wall and approximately 30 mm of ascites were observed.

The final diagnosis was biliary peritonitis following thoracic duct embolization for chylothorax treatment. The critical finding was the high-density nodule observed on the gallbladder wall, which corresponded to lipiodol deposition following penetration of the percutaneous interventional needle into the gallbladder wall.

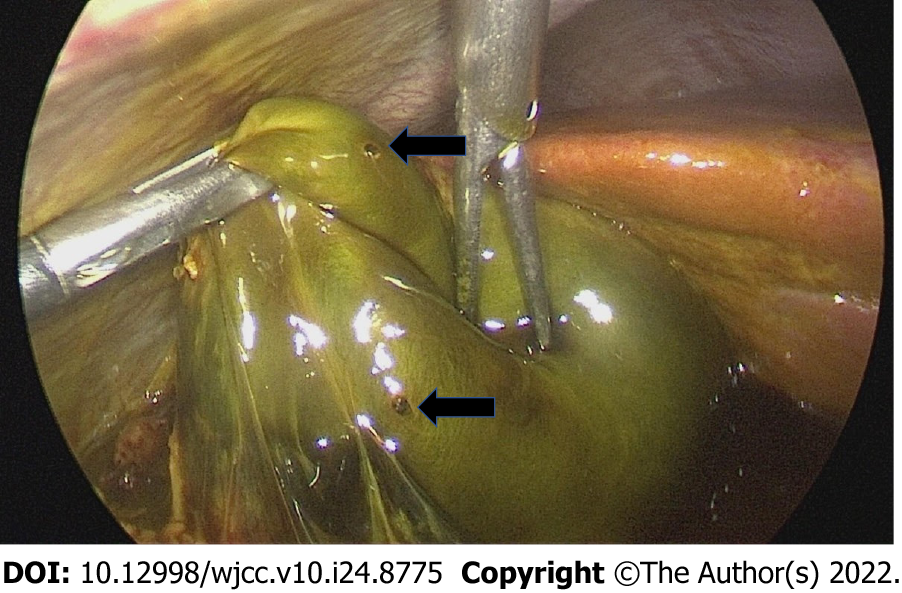

The patient underwent emergency laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The surgeon described 300 mL of bile fluid in the abdominal cavity. The gallbladder was inflamed and covered with greater omentum. The surgeon diagnosed biliary peritonitis in this case. Two holes (approximately 1 mm) were identified in the base and funnel of the gallbladder (Figure 5), suggesting penetration of the gallbladder wall by the percutaneous interventional needle.

After surgery, the patient improved clinically, and the chylothorax output gradually resolved after several weeks. Inflammatory markers remained slightly elevated, and bilirubin returned to the normal range within 5 days: WBC, 9.3 G/L; neutrophils, 82%; CRP, 2.84 mg/dL; and total/direct bilirubin, 3.2/12.2 µmol/L. Abdominal ultrasound showed mild fat stranding around the gallbladder bed and 24 mm of right pleural effusion. The patient was discharged from the hospital 5 days after surgery.

Lymphatic intervention was first described by Cope et al[5], and advances in interventional techniques continue to be developed. The efficacy of lymphatic intervention has been reported by many authors[2,6,7]. Thoracic duct embolization is a new and minimally invasive approach with a high success rate and low morbidity and mortality rates[2]. Cope and Kaiser reported a response rate of 73.8% after thoracic duct embolization with no morbidity or mortality[4]. The overall clinical success rate reported by Pamarthi et al[3] was 72%, and Itkin et al[7] reported a success rate of 90%.

According to the Society of Interventional Radiology Clinical Practice Guidelines, post-intervention complications can be categorized as major or minor complications[8]. Major complications of lymphatic interventions include pulmonary or portal vein embolism caused by glue or guidewire fragment retention. Minor complications often include anesthesia side effects, skin injuries, or perihepatic hematoma[3]. In addition, some delayed mild complications as observed by Laslett et al[9] are lower-extremity edema and chronic diarrhea.

Cope et al[4] reported no complications associated with thoracic duct embolization. Pamarthi et al[3] and Itkin et al[7] reported complication rates of 6.7% and 3%, respectively. Although limited data are available regarding complications, several articles have reported pulmonary embolisms associated with glue, chylous ascites, perihepatic hematoma, bile leakage, or bile peritonitis[3,10,11].

As chylothorax in this patient lasted for 1 mo, not an emergency condition, we decided to treat after a multidisciplinary consultation. Therefore, thoracic duct embolization was performed 3 days after hospitalization. Our patient experienced moderate–severe abdominal pain and fever following thoracic duct embolization, which increased over several days. A contrast-enhanced abdominal CT performed immediately after the intervention revealed that the gallbladder wall was thick and edematous, with peripancreatic fluid extending to the bilateral anterior pararenal space and paracolic gutters. The initial diagnosis was pancreatitis, which is also an extremely uncommon complication following thoracic duct embolization[12]. Unfortunately, the clinical presentation, laboratory tests, and imaging with contrast-enhanced abdominal CT 3 days later were not compatible with the initial diagnosis. We reviewed the initial CT images and realized that we missed a critical sign: a small, high-density nodule in the gallbladder wall, corresponding to lipiodol deposition due to penetration of the percutaneous interventional needle into the gallbladder wall. As the needle punctured through the right abdominal wall, it penetrated into the gallbladder. Although this is a rare complication infrequently reported in the literature, we suggest that the cisterna chyli should be accessed under DSA accompanied by ultrasound in order to avoid accidental puncture in the future. The patient had symptoms of peritonitis, and bile in the abdominal cavity was confirmed intraoperatively. Thus, the final diagnosis was biliary peritonitis. This case serves as a reminder for clinicians and radiologists of the importance of correct diagnosis following the initial CT scan to allow for timely cholecystectomy.

We report a rare case of cholecystitis following thoracic duct embolization to treat chylothorax due to penetration of the interventional needle into the gallbladder wall. Although thoracic duct embolization is considered to be a safe and minimally invasive method, several major complications may occur. Severe or persistent abdominal pain after intervention should be investigated using imaging findings and laboratory results to diagnose complications following thoracic duct embolization in a timely manner.

| 1. | Bojanapu S, Khan YS. Thoracic Duct Leak. 2022 May 8. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Chen E, Itkin M. Thoracic duct embolization for chylous leaks. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2011;28:63-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Pamarthi V, Stecker MS, Schenker MP, Baum RA, Killoran TP, Suzuki Han A, O'Horo SK, Rabkin DJ, Fan CM. Thoracic duct embolization and disruption for treatment of chylous effusions: experience with 105 patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2014;25:1398-1404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cope C, Kaiser LR. Management of unremitting chylothorax by percutaneous embolization and blockage of retroperitoneal lymphatic vessels in 42 patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2002;13:1139-1148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cope C, Salem R, Kaiser LR. Management of chylothorax by percutaneous catheterization and embolization of the thoracic duct: prospective trial. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1999;10:1248-1254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | van Goor AT, Kröger R, Klomp HM, de Jong MA, van den Brekel MW, Balm AJ. Introduction of lymphangiography and percutaneous embolization of the thoracic duct in a stepwise approach to the management of chylous fistulas. Head Neck. 2007;29:1017-1023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Itkin M, Kucharczuk JC, Kwak A, Trerotola SO, Kaiser LR. Nonoperative thoracic duct embolization for traumatic thoracic duct leak: experience in 109 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:584-89; discussion 589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 255] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sacks D, McClenny TE, Cardella JF, Lewis CA. Society of Interventional Radiology clinical practice guidelines. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2003;14:S199-S202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1143] [Cited by in RCA: 1366] [Article Influence: 71.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Laslett D, Trerotola SO, Itkin M. Delayed complications following technically successful thoracic duct embolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012;23:76-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Boffa DJ, Sands MJ, Rice TW, Murthy SC, Mason DP, Geisinger MA, Blackstone EH. A critical evaluation of a percutaneous diagnostic and treatment strategy for chylothorax after thoracic surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;33:435-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gaba RC, Owens CA, Bui JT, Carrillo TC, Knuttinen MG. Chylous ascites: a rare complication of thoracic duct embolization for chylothorax. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2011;34 Suppl 2:S245-S249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bédat B, Scarpa CR, Sadowski SM, Triponez F, Karenovics W. Acute pancreatitis after thoracic duct ligation for iatrogenic chylothorax. A case report. BMC Surg. 2017;17:9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Vietnam

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Mechineni A; Moshref L, Saudi Arabia; Yasukawa K, Japan S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Ma YJ