Published online Aug 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i23.8406

Peer-review started: April 12, 2022

First decision: May 9, 2022

Revised: May 18, 2022

Accepted: July 6, 2022

Article in press: July 6, 2022

Published online: August 16, 2022

Processing time: 111 Days and 4.5 Hours

Acute iatrogenic colorectal perforation (AICP) is a serious adverse event, and immediate AICP usually requires early endoscopic closure. Immediate surgical repair is required if the perforation is large, the endoscopic closure fails, or the patient's clinical condition deteriorates. In cases of delayed AICP (> 4 h), surgical repair or enterostomy is usually performed, but delayed rectal perforation is rare.

A 53-year-old male patient underwent endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) at a local hospital for the treatment of a laterally spreading tumor of the rectum, and the wound was closed by an endoscopist using a purse-string suture. Unfortunately, the patient then presented with delayed rectal perforation (6 h after ESD). The surgeons at the local hospital attempted to treat the perforation and wound surface using transrectal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM); however, the perforation worsened and became enlarged, multiple injuries to the mucosa around the perforation and partial tearing of the rectal mucosa occurred, and the internal anal sphincter was damaged. As a result, the perforation became more complicated. Due to the increased bleeding, surgical treatment with suturing could not be performed using TEM. Therefore, the patient was sent to our medical center for follow-up treatment. After a multidisciplinary discussion, we believed that the patient should undergo an enterostomy. However, the patient strongly refused this treatment plan. Because the position of the rectal perforation was relatively low and the intestine had been adequately prepared, we attempted to treat the complicated delayed rectal perforation using a self-expanding covered mental stent (SECMS) in combination with a transanal ileus drainage tube (TIDT).

For patients with complicated delayed perforation in the lower rectum and adequate intestinal preparation, a SECMS combined with a TIDT can be used and may result in very good outcomes.

Core Tip: In this case, the diagnosis of perforation was delayed, the nearby rectal mucosa and internal anal sphincter were extensively damaged. Rectoscopic or laparoscopic repair was difficult. The alternative approach is proximal enterostomy and subsequent stoma reversal. but the patient refused. The perforation was in the lower rectum, the bowel was well prepared. The treatment could be successful as long as the leakage of intestinal contents into the abdominal cavity were prevented, the wound was protected from contamination. The self-expanding covered mental stent covers the perforation, promotes repair and prevents the stenosis, and the transanal ileus drainage tube drains the intestinal contents. The combination achieved the goals.

- Citation: Cheng SL, Xie L, Wu HW, Zhang XF, Lou LL, Shen HZ. Metal stent combined with ileus drainage tube for the treatment of delayed rectal perforation: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(23): 8406-8416

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i23/8406.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i23.8406

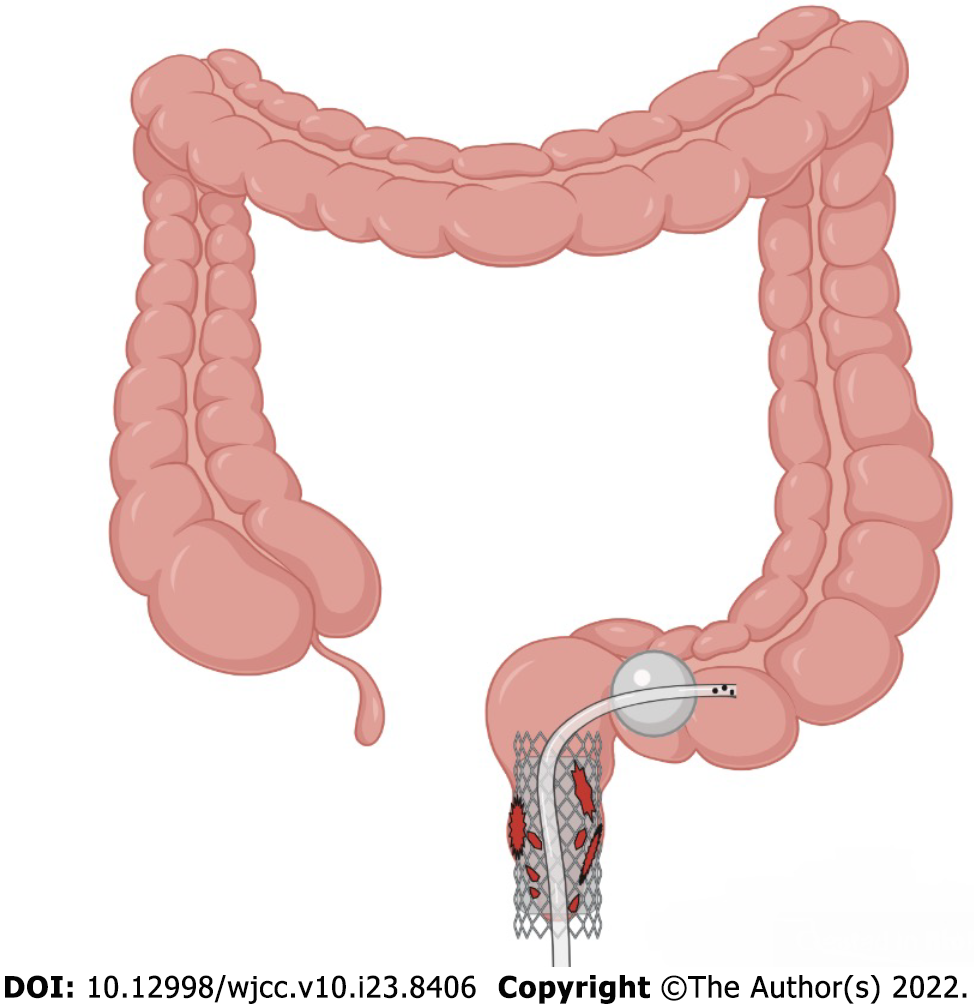

Acute iatrogenic colorectal perforation (AICP) is a serious adverse event, but it is rare. The common causes of perforation include mechanical injury during colonoscopy insertion, deep cauterization during therapeutic colonoscopy, and intestinal wall tearing during endoscopic balloon dilation[1]. There is still no common method for treating AICP at present, and many factors affect the establishment of a treatment plan after perforation. In general, however, immediate AICP tends to require endoscopic closure by using through-the-scope (TTS) clips and over-the-scope clips (OTSCs)[2]. Immediate surgical repair is required if the perforation is large, if the endoscopic closure fails, or if the patient's clinical condition deteriorates. Delayed AICP (> 4 h) usually requires surgical repair or enterostomy[1]. Is there a novel treatment endoscopists could use help some patients who would otherwise need surgery or enterostomy avoid surgery? Here, we report a case of a complicated delayed rectal perforation after endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). We successfully placed a self-expanding covered mental stent (SECMS) in his rectum and a transanal ileus drainage tube (TIDT) in his colon distal to the stent, and he eventually avoided surgery and recovered well (Figure 1). This is the first time that a SECMS combined with a TIDT has been used to treat a complicated delayed rectal perforation after ESD.

The patient is a 53-year-old man who was admitted to our hospital because of delayed perforation (> 6 h) after ESD of the rectum with a failed transrectal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM), and the patient had abdominal pain and fever.

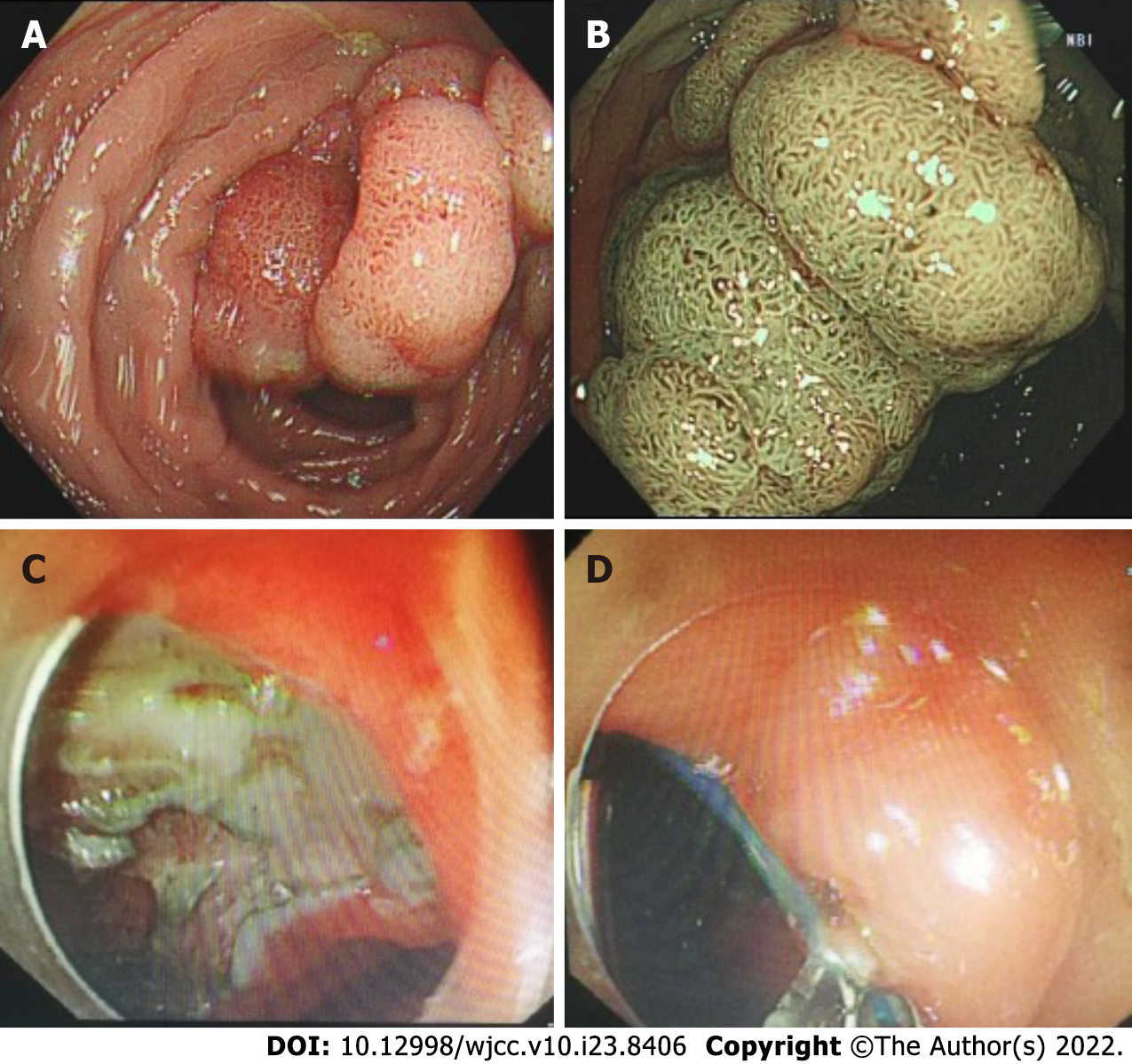

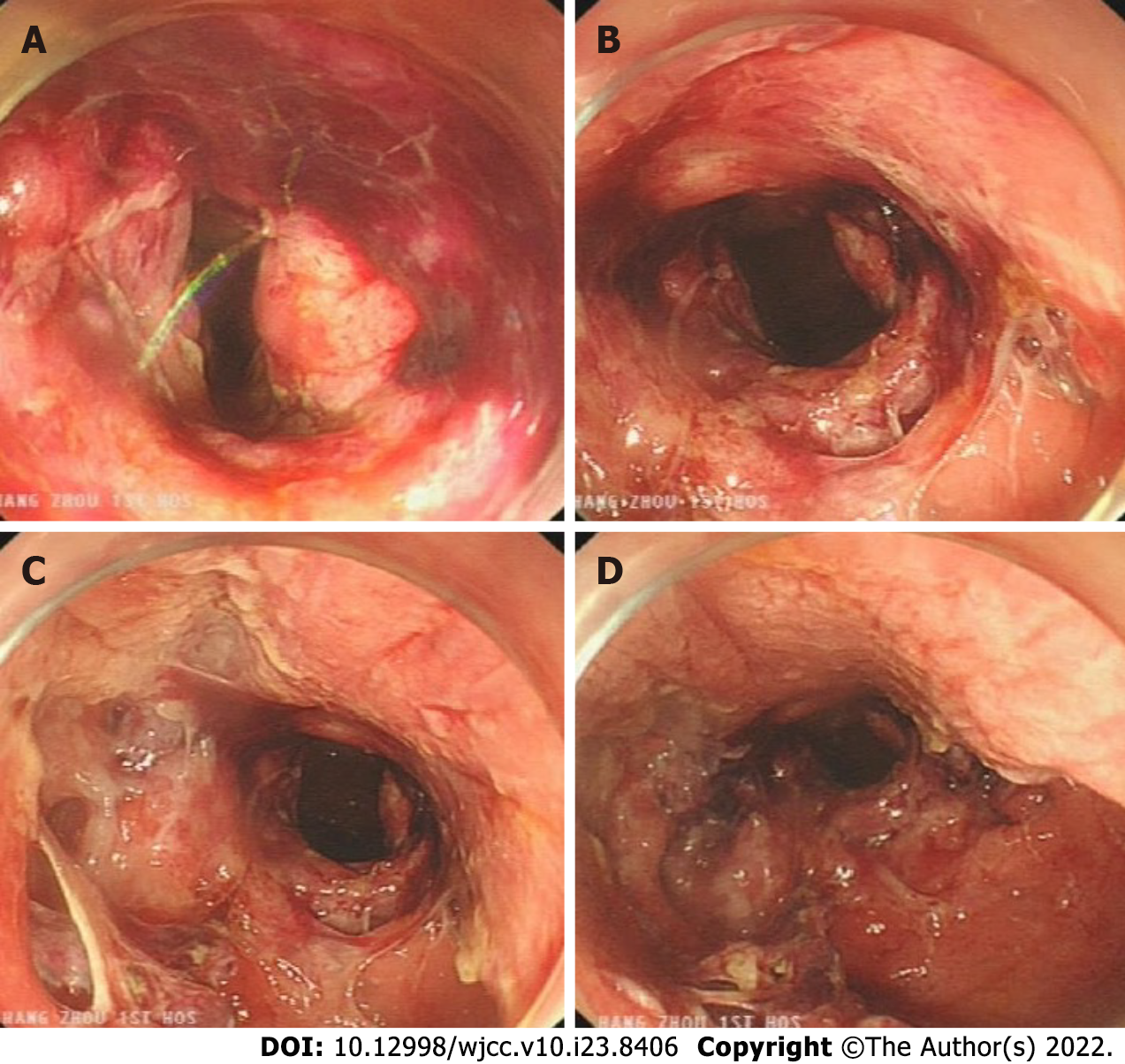

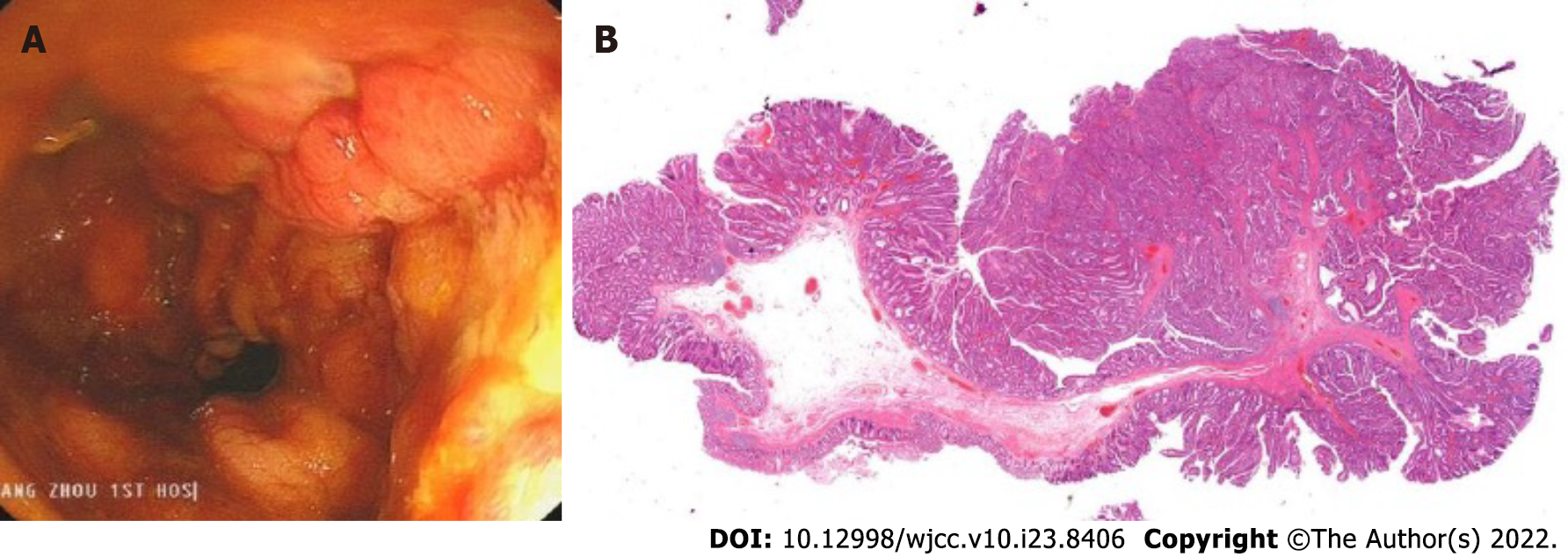

The patient's out-of-hospital diagnosis was a laterally spreading tumor of the rectum, which was 25 mm × 20 mm in size and approximately 3-5 cm from the anus (Figure 2A and B). The patient eventually underwent rectal ESD, which was performed by an inexperienced endoscopist (fewer than 50 cases), at a local hospital. According to the operation records of the local hospital, there was considerable bleeding during the ESD procedure, and the wound surface was large. It was impossible to accurately determine whether there was a perforation during the procedure, so the endoscopist decided to close the wound surface with a purse-string suture technique (Figure 2C and D). However, the patient developed severe abdominal pain and fever (39.4 °C) six hours after ESD. A computed tomography (CT) scan performed at the local hospital indicated gas accumulation in the rectum and perineum. Considering the rectal perforation, the anorectal surgeons at the local hospital attempted to treat the perforation and wound surface with TEM. The wound surface was obviously congested and edematous. The anorectal surgeons first attempted to remove the clips and sutures. This operation resulted in worsening of the original perforation, enlargement of the perforation, multiple injuries to the mucosa around the perforation, partial tearing of the rectal mucosa and injury to the internal anal sphincter (Figure 3). Due to the significant bleeding, surgical suturing under direct vision was not possible. Hence, gauze and the anal canal were placed within the rectum, and the patient was transferred to our hospital for further emergency treatment.

The patient was previously in good health without any other underlying medical conditions.

There have no difference.

The patient’s physical examination results were as follows: temperature of 37.7 °C (after intravenous injection of dexamethasone), pulse rate of 81/min, and BP of 155/100 mmHg. The patient had no cardiorespiratory symptoms, but he did have abdominal distension, muscle tension, middle and lower abdominal tenderness (+), rebound pain (+), significant swelling of the scrotum, hip, and perineum, and subcutaneous crepitus.

The patient’s laboratory examination results were as follows: WBC of 11.6 × 109/L, neutrophil count of 82.1%, CRP level of 158 mg/L.

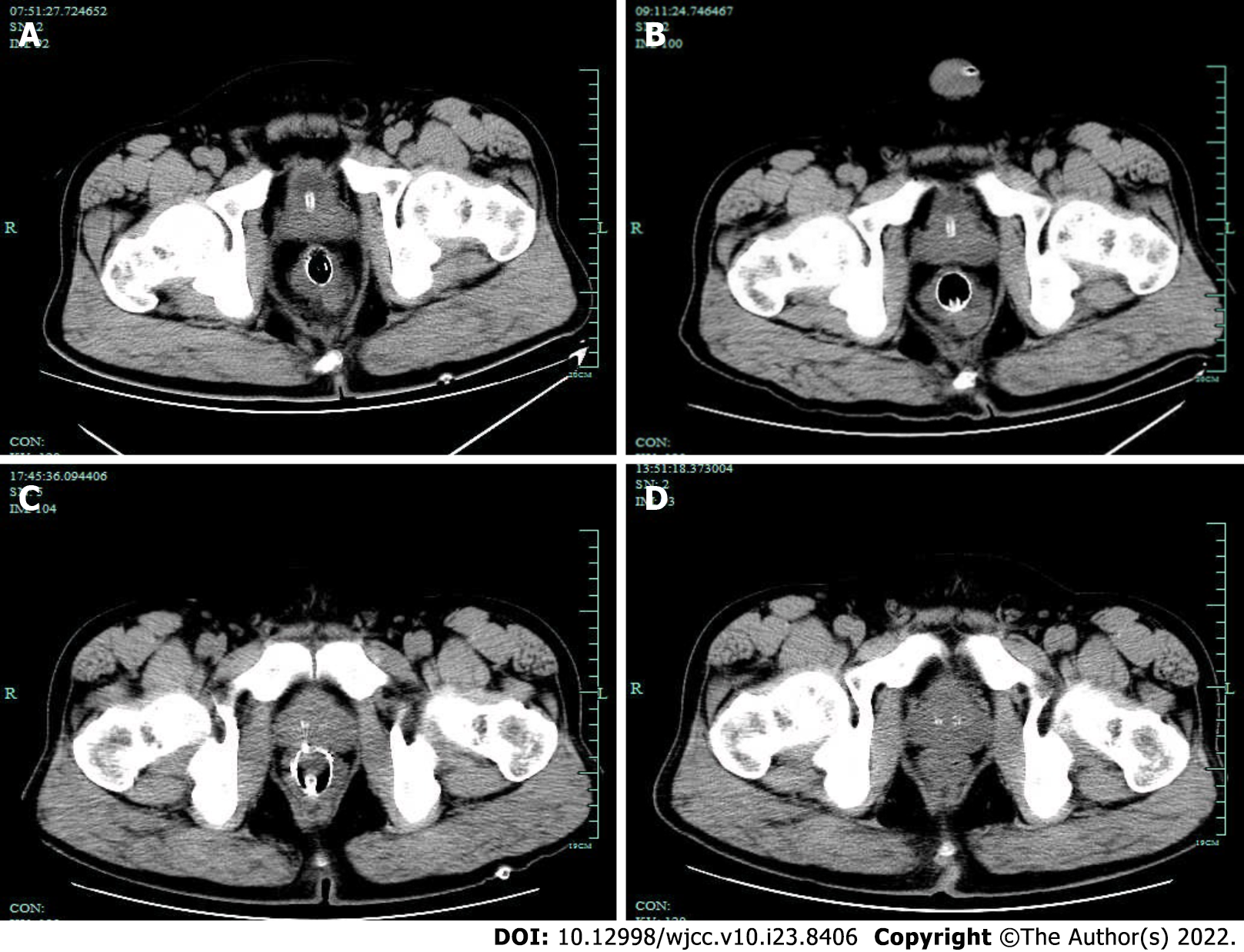

The CT from the local hospital showed that the patient had gas around the intestines and pneumatosis under the perianal, perineal and scrotal skin.

The anorectal surgery department suggested a proximal enterostomy, regular digital rectal examination during the period to prevent stenosis, and subsequent stoma reversal with a total treatment time of approximately 3 mo.

The gastroenterology department recommended isolating the wound surface, avoiding fecal contamination, and controlling infection. They also recommended preventing stricture of the rectal scar contracture.

The patient was concerned that this operation would be traumatic and could significantly affect his quality of life, and the patient firmly refused to undergo surgery and enterostomy.

The final result of discussion was that if a cure was needed, two goals must be achieved: (1) Avoiding wound surface contamination by intestinal contents and infection caused by leakage into the abdominal cavity; and (2) Isolating the damaged wound surface so that it has enough time to heal and preventing rectal stenosis.

A SECMS and a TIDT could be used to help us achieve the abovementioned goals without the need for surgery.

Complicated delayed rectal perforation after ESD.

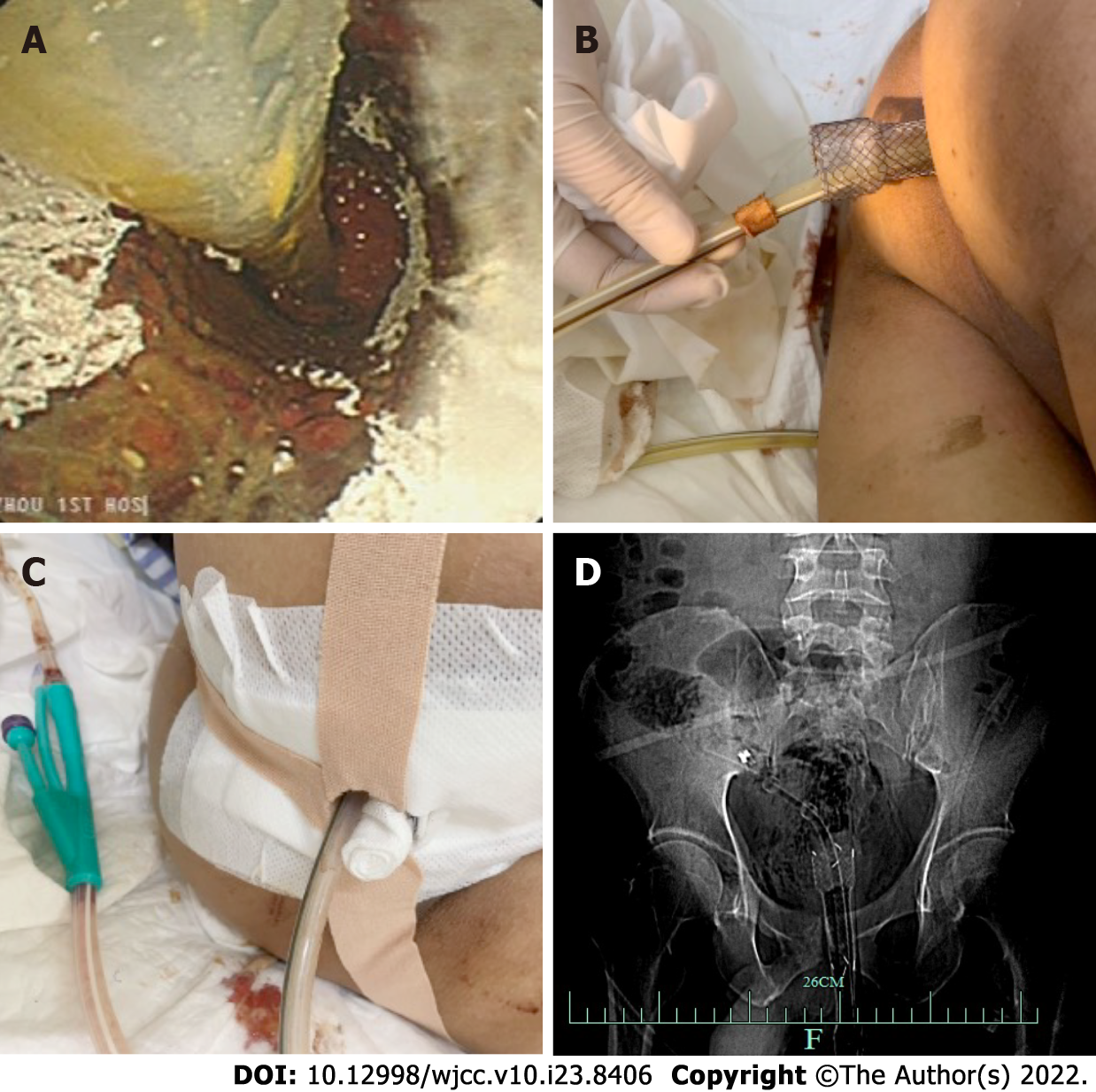

The patient fasted and was administered anti-infection treatment. The patient was placed in the left lateral decubitus position under compound intravenous anesthesia. A SECMS was placed in the rectum to cover the rectal perforated area to prevent fecal contamination. Since the internal anal sphincter was also damaged, the end of the stent was exposed to the outside of the anus by approximately 1.5-2 cm, and it was convenient for fixation. Fortunately, the patient did not develop significant side effects associated with low-rectal SECMS, which include anal pain and tenesmus. The SECMS was able to achieve an expanded fit to the rectal wall. We believed that isolation of the perforated area was important to promote successful wound healing and to further reduce fecal contamination; thus, we also placed a TIDT through the colonoscope. The TIDT balloon was located approximately 10 cm distal to the stent, and 30 mL of sterile distilled water was injected into the balloon. The intestinal lumen was closed with a balloon to guide the intestinal contents derived from the proximal colon. The TIDT and the SECMS were finally fixed with medical tape (Figure 4). Continuous negative pressure (approximately 100 mmHg) was applied to the TIDT to remove the intestinal contents. In this case, the SECMS was 22 mm in diameter, 90 mm in usable length and 120 mm in total length (Sewoon Medical Co., Led. Chungcheongnam-do, South Korea). Its outer diameter was 22 Fr, and it was 120 cm in length (Create Medic Co., Dalian, Liaoning Province, China).

Fasting, anti-infection treatment, fluid replacement and parenteral nutrition support were continued, and the status of the stents and TIDT were observed every day. Negative pressure was continuously applied to the TIDT to reduce the intestinal pressure and to avoid fecal contamination of the wound surface. The TIDT was rinsed every day to avoid obstruction, and the stents and the TIDT were prevented from shifting. The dressing was changed regularly to keep the anal circumference clean (Figure 5).

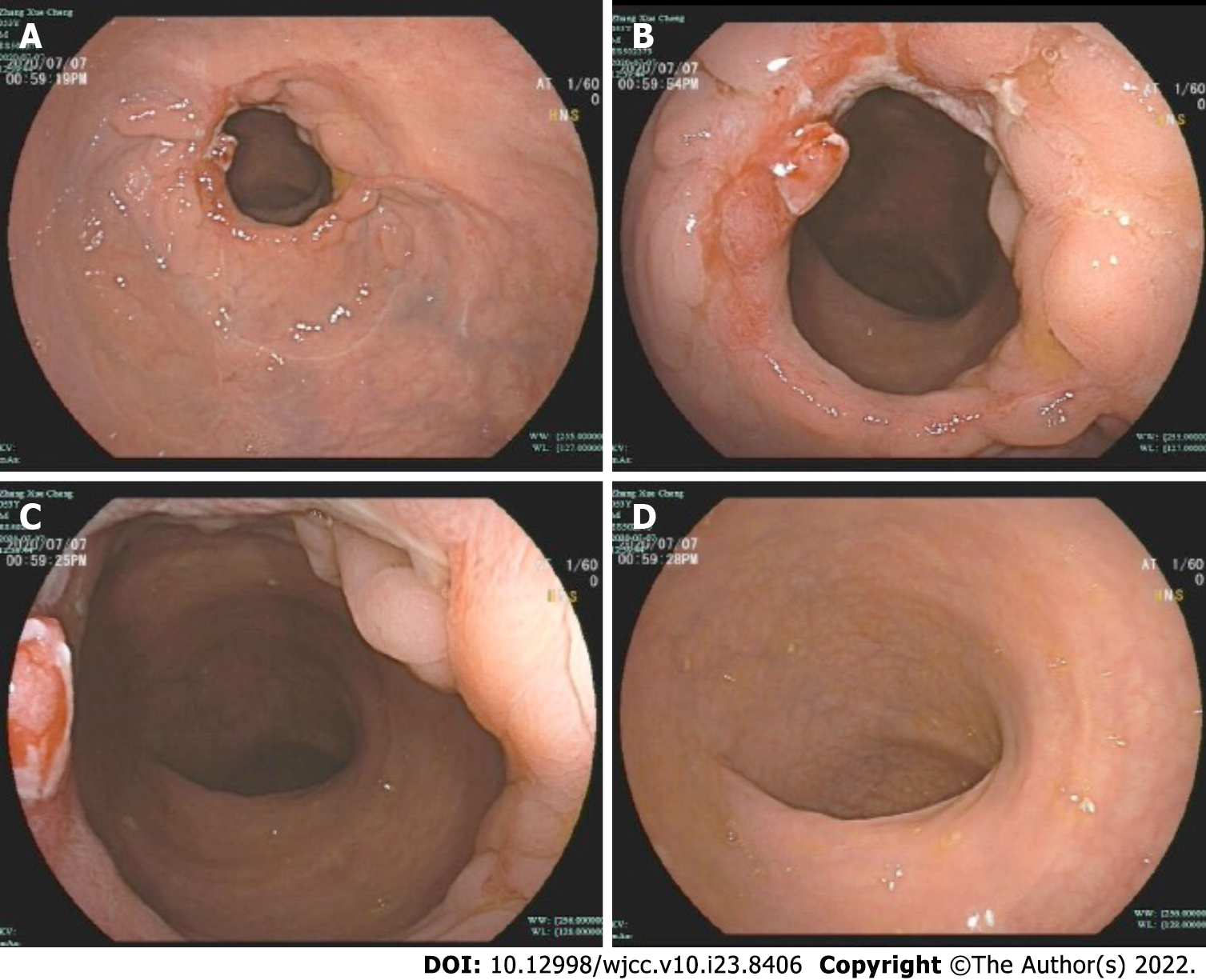

The SECMS was removed, and the patient’s intestines were cleaned. The perforation and injury were almost unobservable (Figure 6A). The TIDT was not removed, and the patient began to consume a liquid diet. The patient's postoperative pathology was tubular-villous adenoma with some high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (intramucosal carcinoma) (Figure 6B).

The TIDT was removed.

A follow-up abdominal CT was performed, and the patient was discharged. During the treatment, beginning on Day 2, the patient’s body temperature returned to normal, and the patient’s abdominal pain and distension improved. The subcutaneous emphysema that was present in the patient’s buttocks and perineum gradually resolved. The hemogram gradually decreased to normal, and a total of four abdominal CT scans were obtained during hospitalization. A gradual decrease in the free gas in the pelvis could be observed (Figure 7).

The patient occasionally had a small amount of bloody stool after discharge, but the patient had no other symptoms. On the 42nd day, the patient underwent a colonoscopy and recovered well (Figure 8).

Colonoscopy is generally considered a safe procedure, but even so, important adverse events such as AICP, which are usually serious, deserve our attention[1]. The probability of diagnostic colonoscopy perforation is 0.03%-0.8%, but the risk of therapeutic colonoscopy perforation is higher, especially with regard to colorectal ESD; the risk of therapeutic colonoscopy perforation is related to the lesion size, lesion location, patient history and operator experience[3]. Previous studies have reported a high rate of perforation ranging from 4% to 10%[1]. Usually, perforations can be identified early because most cases of perforation are obvious to the endoscopist, and delayed perforation is rare[4]. Because of the delayed diagnosis in these cases, the consequences are more serious. The treatment patterns for AICP have been changing[4]. Between 1996 and 2012, the rate of surgery to treat perforation was 93.3%, and the mortality rate was 8.3%. After 2012, the rate of surgery to treat perforation was 27.2%, and the mortality rate was 0%. The length of hospital stay was reduced from 6.9 to 4 d. Overall, advances in endoscopic closure have resulted in fewer surgical procedures.

The recommendations from the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy[1] suggest that endoscopic treatment should be considered immediately for AICP (< 4 h) due to the need for adequate bowel preparation. Small holes (< 10 mm) and TTS clips can be used, while OTSCs are recommended for large perforations. Furthermore, attempts to immediately close AICPs endoscopically depend on a variety of factors, including the size and cause of AICP, the endoscopist's experience, and the equipment available at the time. It has been reported that the success rate of TTS clips is 60% and that of OTSCs is 100%[4]. In the largest retrospective observation case series in Europe that evaluated perforation results, 83.3% of endoscopists observed cases of perforation that were successfully closed with TTS clips. In addition to the widely used TTS clips and OTSCs mentioned above, there are also reports that band ligation, purse-string sutures, and suture instruments can be used to endoscopically close AICPs[1,5-7]; however, the relevant research is limited. In this patient, whether perforation occurred during ESD could not be accurately determined, so the endoscopists chose to use purse-string sutures to completely close the wound. However, this treatment failed, resulting in a subsequent delayed perforation; therefore, the patient developed severe abdominal pain and fever.

The best management for delayed perforations (> 4 h), perforations with a large diameter, perforations with the presence of fecal contents, perorations associated with complicated or failed endoscopic closure, and perforations in patients with deteriorating clinical conditions is surgery[2,8,9]. Minimally invasive laparoscopic treatment of perforations has become the preferred surgical option and is now widely accepted and practiced. A prompt diagnosis of perforation is very important. If the diagnosis is made within 12 h, the fecal contamination is only approximately 30%. If the diagnosis is made 24 h after perforation, almost all patients will suffer from peritoneal fecal contamination, thus requiring a stoma. The average hospitalization time of patients undergoing surgery is 17.8 days[10]. TEM repair is also theoretically an approach for treating lower rectal perforation, but transrectal endoscopy may damage the anal sphincter[11-14]. This patient had an endoscopically observable injury to the internal anal sphincter. In our case, delayed perforation was diagnosed, the patient’s bowel had been adequately prepared before ESD, and the lesion site was relatively low and below the peritoneal reflection. The first choice was to repair the perforation through transrectal endoscopy. However, the TEM repair also failed and had serious consequences. Because of the conditions described above, both laparoscopic and laparotomy repair are almost impossible, and partial rectal resection and fecal diversion surgery would have been the only options for this patient. However, this surgery may be accompanied by a higher incidence risk, and there is also risk associated with the required general anesthesia. Additionally, the stoma may significantly reduce the quality of life of patients.

A covered stent has the potential to cover the wound surface. It is possible to reduce the leakage of fluid and bacteria into the tissue surrounding the rectum, thereby isolating the perforation area. Then, a covered stent can be easily removed. The placement of the stent can allow the perforation to heal in an appropriate manner, which can effectively reduce the possibility of scarring and stenosis. Another advantage of the stent is that it can effectively prevent the development of a proximal intestinal diversion stoma[15-19]. TIDTs with balloons have a very good therapeutic effect in the prevention and treatment of anastomotic leakage. The use of balloon to seal the intestinal lumen can guide the intestinal contents from the proximal colon and can isolate the anastomosis, which significantly reduces the contamination of the anastomosis site by feces and reduces rectal pressure during defecation to promote the healing of the anastomosis[20]. We designed an effective protocol using a SECMS combined with a TIDT for the treatment of this complicated delayed rectal perforation. This is the first report regarding the treatment of this condition.

It has been previously reported that the placement of an enteral stent during radical resection of rectal cancer can effectively prevent postoperative anastomotic leakage after the treatment of lower rectal cancer[13,14]. SECMSs have been reported to treat anastomotic leakage after colorectal cancer surgery[15], and the success rate of the treatment is 80%[16]. There are reports of the use of SECMSs to treat late rectal perforations after severe explosive injury[17]. The patient's injury was located in the middle of the rectum, the stent was easily inserted into the rectum, and the perforated area was completely covered by the SECMS at the end of the procedure. The patient eventually recovered. In this case, after the stent was placed, the perforation and wound surface of the patient were completely covered, and the liquid in the intestinal tract did not easily leak to the periphery of the rectum, thus protecting the wound surface and effectively preventing the occurrence of stenosis in the later stage.

In addition to stent therapy, studies have shown that TIDTs, which are placed 3-5 cm above the anastomosis, can be used to prevent anastomotic leakage after rectal cancer resection[14,18], and some studies have shown that anastomotic leakage cannot be prevented[19]. After the intestinal cavity is sealed by the balloon, artificial intestinal obstruction may occur, which easily promotes intestinal peristalsis, and the TIDTs are easily discharged. Therefore, perianal fixation of the drainage tubes is very important[20]. It is easy to wash and remove the contents of TIDTs, which can effectively maintain the cleanliness of the intestinal fluid at the anastomosis. In this case, a TIDT was placed in the patient for aspiration and irrigation during treatment, which effectively reduced rectal pressure, prevented contamination of the wound surface by fecal fluid, and promoted perforation repair.

In our case, we used both an SECMS and a TIDT to treat a complicated delayed rectal perforation after ESD, and this approach achieved successful coverage of the perforated area. This treatment helped to prevent fecal contamination of the wound and rectal stenosis. This protocol is suitable for patients with complicated delayed perforation in the lower rectum and with adequate intestinal preparation. A SECMS combined with a TIDT can be used and may achieve very good outcomes. Therefore, this case is a good reference for the future treatment of similar situations.

| 1. | Paspatis GA, Arvanitakis M, Dumonceau JM, Barthet M, Saunders B, Turino SY, Dhillon A, Fragaki M, Gonzalez JM, Repici A, van Wanrooij RLJ, van Hooft JE. Diagnosis and management of iatrogenic endoscopic perforations: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Position Statement - Update 2020. Endoscopy. 2020;52:792-810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Paspatis GA, Dumonceau JM, Barthet M, Meisner S, Repici A, Saunders BP, Vezakis A, Gonzalez JM, Turino SY, Tsiamoulos ZP, Fockens P, Hassan C. Diagnosis and management of iatrogenic endoscopic perforations: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Position Statement. Endoscopy. 2014;46:693-711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 236] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Kothari ST, Huang RJ, Shaukat A, Agrawal D, Buxbaum JL, Abbas Fehmi SM, Fishman DS, Gurudu SR, Khashab MA, Jamil LH, Jue TL, Law JK, Lee JK, Naveed M, Qumseya BJ, Sawhney MS, Thosani N, Yang J, DeWitt JM, Wani S; ASGE Standards of Practice Committee Chair. ASGE review of adverse events in colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;90:863-876.e33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Paspatis GA, Fragaki M, Velegraki M, Mpitouli A, Nikolaou P, Tribonias G, Voudoukis E, Karmiris K, Theodoropoulou A, Vardas E. Paradigm shift in management of acute iatrogenic colonic perforations: 24-year retrospective comprehensive study. Endosc Int Open. 2021;9:E874-E880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Han JH, Park S, Youn S. Endoscopic closure of colon perforation with band ligation; salvage technique after endoclip failure. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:e54-e55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ryu JY, Park BK, Kim WS, Kim K, Lee JY, Kim Y, Park JY, Kim BJ, Kim JW, Choi CH. Endoscopic closure of iatrogenic colon perforation using dual-channel endoscope with an endoloop and clips: methods and feasibility data (with videos). Surg Endosc. 2019;33:1342-1348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kantsevoy SV, Bitner M, Hajiyeva G, Mirovski PM, Cox ME, Swope T, Alexander K, Meenaghan N, Fitzpatrick JL, Gushchin V. Endoscopic management of colonic perforations: clips versus suturing closure (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84:487-493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Pilgrim CH, Nottle PD. Laparoscopic repair of iatrogenic colonic perforation. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2007;17:215-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cho SB, Lee WS, Joo YE, Kim HR, Park SW, Park CH, Kim HS, Choi SK, Rew JS. Therapeutic options for iatrogenic colon perforation: feasibility of endoscopic clip closure and predictors of the need for early surgery. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:473-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | La Torre M, Velluti F, Giuliani G, Di Giulio E, Ziparo V, La Torre F. Promptness of diagnosis is the main prognostic factor after colonoscopic perforation. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:e23-e26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jakubauskas M, Jotautas V, Poskus E, Mikalauskas S, Valeikaite-Tauginiene G, Strupas K, Poskus T. Fecal incontinence after transanal endoscopic microsurgery. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018;33:467-472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Marinello FG, Curell A, Tapiolas I, Pellino G, Vallribera F, Espin E. Systematic review of functional outcomes and quality of life after transanal endoscopic microsurgery and transanal minimally invasive surgery: a word of caution. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2020;35:51-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Li JJ, Li DW, Yang W, Mo DC, Sun D, Peng L. [Application of intestinal stent in prevention of anastomotic leakage after rectal cancer operation]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2020;23:602-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Choy KT, Yang TWW, Heriot A, Warrier SK, Kong JC. Does rectal tube/transanal stent placement after an anterior resection for rectal cancer reduce anastomotic leak? Int J Colorectal Dis. 2021;36:1123-1132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hedrick TL, Kane W. Management of Acute Anastomotic Leaks. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2021;34:400-405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lamazza A, Fiori E, Schillaci A, Sterpetti AV, Lezoche E. Treatment of anastomotic stenosis and leakage after colorectal resection for cancer with self-expandable metal stents. Am J Surg. 2014;208:465-469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ozer MT, Coskun AK, Sinan H, Saydam M, Akay EO, Peker S, Ogunc G, Demirbas S, Peker Y. Use of self-expanding covered stent and negative pressure wound therapy to manage late rectal perforation after injury from an improvised explosive device: a case report. Int Wound J. 2014;11 Suppl 1:25-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wang Z, Liang J, Chen J, Mei S, Liu Q. Effectiveness of a Transanal Drainage Tube for the Prevention of Anastomotic Leakage after Laparoscopic Low Anterior Resection for Rectal Cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2020;21:1441-1444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zhao S, Zhang L, Gao F, Wu M, Zheng J, Bai L, Li F, Liu B, Pan Z, Liu J, Du K, Zhou X, Li C, Zhang A, Pu Z, Li Y, Feng B, Tong W. Transanal Drainage Tube Use for Preventing Anastomotic Leakage After Laparoscopic Low Anterior Resection in Patients With Rectal Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg. 2021;156:1151-1158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhang D, He K, Qiu H, Zhuang Z, Liufu Y, Zhang J, Zeng X. [Usefulness of self-made gasbag double-cannula stool drainage device for prevention of anastomotic leakage following anterior resection]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2017;20:914-918. [PubMed] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, general and internal

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D, D, D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Shariati MBH, Iran; Yap RVC, Philippines S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yan JP