Published online Aug 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i23.8271

Peer-review started: January 20, 2022

First decision: May 11, 2022

Revised: May 23, 2022

Accepted: July 11, 2022

Article in press: July 11, 2022

Published online: August 16, 2022

Processing time: 193 Days and 3.1 Hours

Ataxia with vitamin E deficiency (AVED) is a type of autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia. Clinical manifestations include progressive cerebellar ataxia and movement disorders. TTPA gene mutations cause the disease.

We report the case of a 32-year-old woman who presented with progressive cerebellar ataxia, dysarthria, dystonic tremors and a remarkably decreased serum vitamin E concentration. Brain magnetic resonance images showed that her brainstem and cerebellum were within normal limits. Acquired causes of ataxia were excluded. Whole exome sequencing subsequently identified a novel homozygous variant (c.473T>C, p.F158S) of the TPPA gene. Bioinformatic analysis predicted that F185S is harmful to protein function. After supplementing the patient with vitamin E 400 mg three times per day for 2 years, her symptoms remained stable.

We identified an AVED patient caused by novel mutation in TTPA gene. Our findings widen the known TTPA gene mutation spectrum.

Core Tip: Ataxia with vitamin E deficiency can present as progressive chronic cerebellar ataxia and involuntary movement disorder. Vitamin E supplementation should be initiated as early as possible to stop disease progression.

- Citation: Zhang LW, Liu B, Peng DT. Clinical and genetic study of ataxia with vitamin E deficiency: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(23): 8271-8276

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i23/8271.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i23.8271

Ataxia with vitamin E deficiency (AVED) is a type of autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia (ARCA). The most prominent symptoms include cerebellar ataxia, areflexia, peripheral neuropathy and movement disorder[1,2]. AVED patients may also exhibit retinitis pigmentosa, cardiomyopathy and scoliosis[3,4]. AVED is caused by mutations in the TTPA gene, which encodes the α-tocopherol transfer protein, which in turn binds α-tocopherol and transports vitamin E from hepatocytes to circulating lipoproteins[5]. Vitamin E supplementation may prevent the worsening of the condition of patients with AVED.

To date, the known incidence rate of AVED in China has been low[6]. Here, we report the clinical, biochemical and genetic investigation of a Chinese patient with AVED due to homozygous mutations in the TTPA gene. This patient exhibited progressive cerebellar ataxia, dysarthria and head titubation with markedly low levels of serum vitamin E. After treatment with vitamin E 400 mg three times per day for 2 years, the patient’s neurological symptoms were stabilized.

A 32-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital because of progressive cerebellar ataxia and involuntary head tremors.

When the patient was 14-years-old, she began exhibiting an unsteady gait which worsened to become wide-based and staggering. She also developed slurring of speech and clumsiness of the hands. At 18 years of age, she began having involuntary dystonic head tremors as well.

She had no specific intestinal lesions indicative of malabsorption. Past medical history was unremarkable.

Her parents are cousins. There is no family history of similar neurological disorders.

Neurological examination revealed normal cognitive state, dysarthria, overt head tremor, bilateral dysmetria on nose-finger and heel-shin tests and a wide-based ataxic gait with inability to walk in tandem. Kayser-Fleischer Rings were absent; vision and hearing ability were normal. Motor and sensory examinations yielded normal results apart from areflexia. Romberg’s sign and bilateral Babinski sign were positive; Pes cavus deformity noted. Obvious overt head dystonic tremor, bilateral dysmetria on finger-to- nose and heel-to-shin tests and wide-based gait with inability to walk in tandem. Scale for the assessment and rating of ataxia (SARA) score was 11 [gait 2, stance 2, sitting 0, speech 1, finger chase 1.0 (left 1, right 1), nose-finger test 2.0 (left 2, right 2), fast alternating hand movements 1.0 (left 1, right 1), and heel-shin slide 2.0 (left 2, right 2)].

Routine blood tests, including liver function, autoimmune antibodies, thyroid function, blood smear for acanthocytosis and plasma levels of vitamins (B1, B2, B6, B9, B12, A, D, E), copper and ceruloplasmin were normal. Cerebrospinal fluid was normal including inflammatory, immunological and infectious indices. Electromyography, nerve conduction velocity and brainstem auditory evoked potential were all normal. Initial DNA analyses using capillary electrophoresis of polymerase chain reaction products excluded Friedrich’s ataxia, spinocerebellar ataxia (1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 8, 10, 12, 17) and dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy. The plasma level of total vitamin E detected via high performance liquid chromatography was 0.59 µg/mL (normal: 10.8 ± 3.3 mg/L[7]).

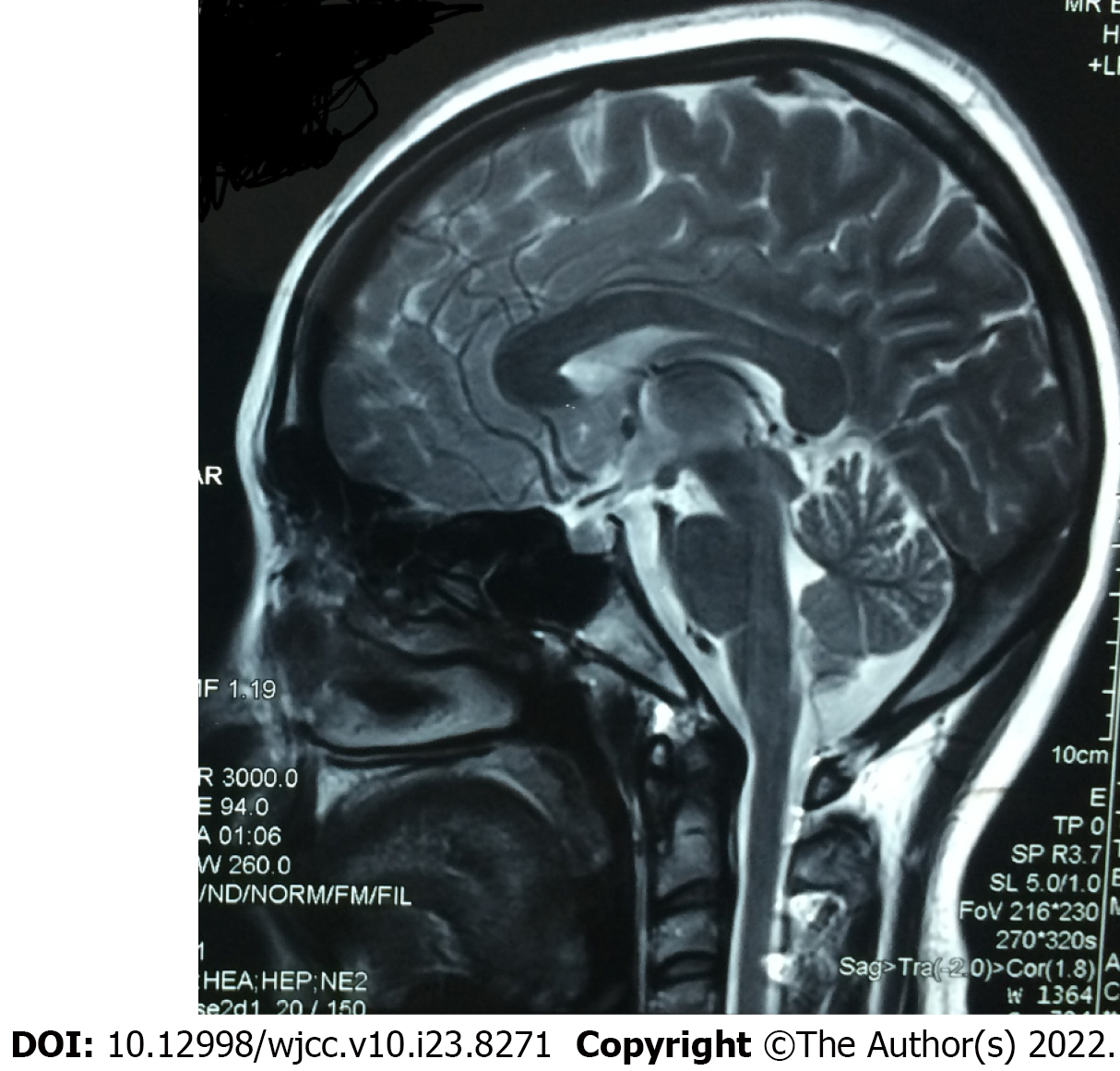

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed no obvious atrophy of brainstem and cerebellum (Figure 1).

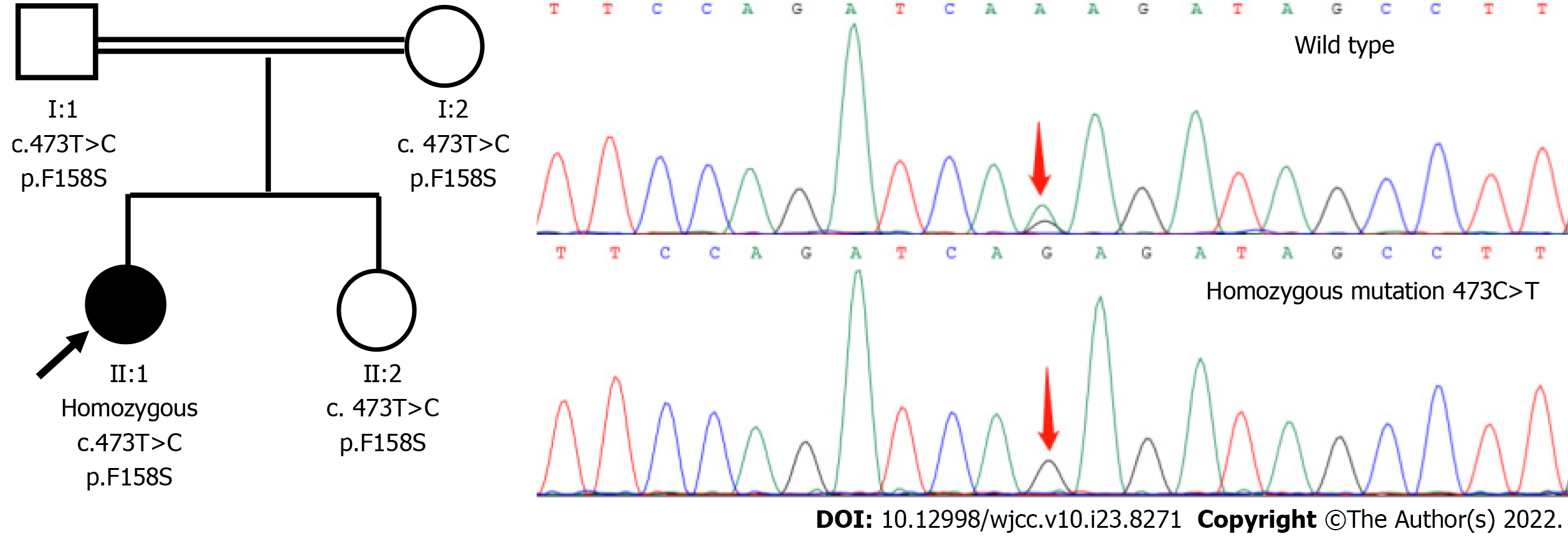

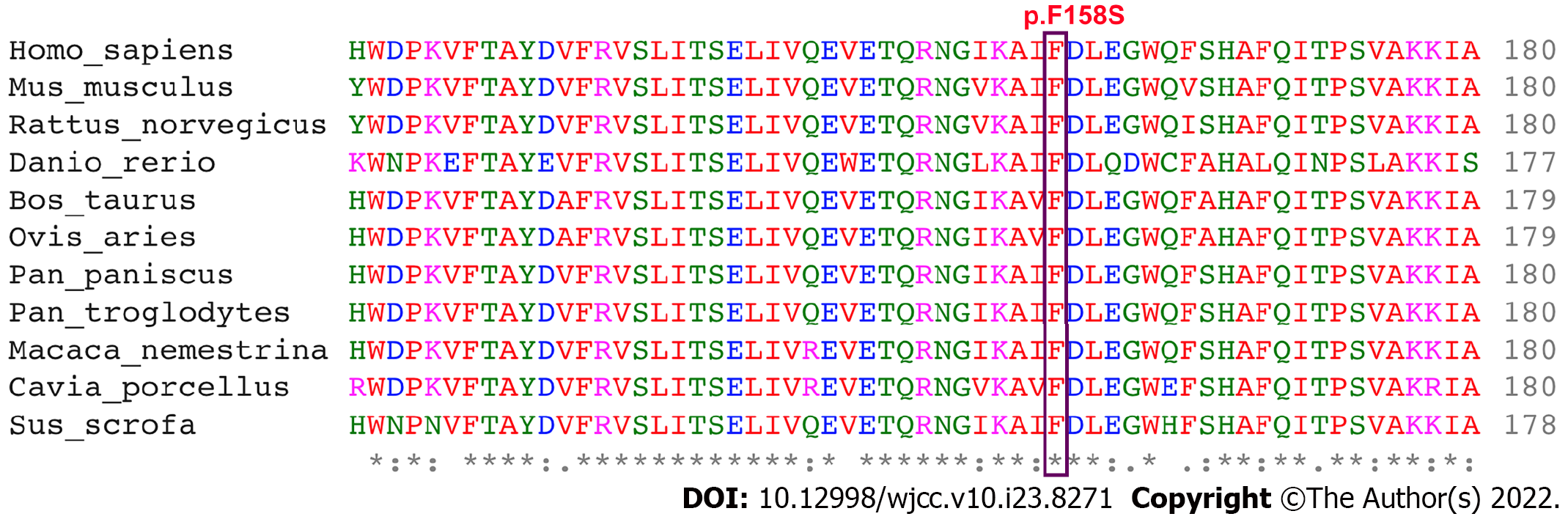

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral leukocytes of the patient and all available family members who gave written informed consent, according to the standard protocol approved by the China-Japan Friendship Hospital. DNA of the proband was subjected to whole exome sequencing (WES) using the Ion Torrent AmpliSeq Exome RDY kit (BGI Tech, Hong Kong). Variant call files were analyzed with Ingenuity Variant Analysis (Qiagen, Redwood City, CA, United States) using an autosomal recessive model. Clean reads were aligned on the human assembly GRCh37 by Burrow-Wheeler aligner. Small insertions/deletions and single nucleotide variants were called by genomic analysis toolkit and annotated by ANNOVAR. Several filtration steps to obtain putative pathogenic variants were processed. The functional effects of protein variants were predicted by Sorting Intolerant from Tolerant (SIFT), PolyPhen2 and MutationTaster. Disease association databases (e.g., HGMD, OMIM and ClinVar) and genetic variation databases (e.g., 1000 Genomes Project, ESP6500 and ExAC) were used in the filtering process as well. Potential pathogenic variants were validated by conventional Sanger sequencing and her family members were included for segregation analysis. We used the transcript sequence (OMIM*600415, NM_000370.3) of the TTPA gene and discovered homozygous variants(c.473C>T, p.Phe185Ser) in the proband. Sanger sequencing confirmed this result and revealed that her parents and the younger sister are heterozygous carriers for 473C>T (Figure 2). This mutation was predicted to be harmful (SIFT: tolerated, Polyphen2: possibly damaging, MutationTaster: disease causing). The 158-phenylalanine residue affected by the mutation were highly conserved in evolution (Figure 3).

The final diagnosis of the presented case was AVED due to TTPA homozygous missense mutation (c.473C>T, p.Phe185Ser) (GRCh37/hg19).

After we detected decreased plasma levels of total vitamin E, supplementation with vitamin E 400 mg three times per day was immediately administered. The patient also kept physical exercises for rehabilitation therapy.

After 2 years of vitamin E supplementation therapy, the symptoms of this patient showed neither improvement nor deterioration. On her last follow-up visit, her SARA score was 11 [gait 2, stance 2, sitting 0, speech 1, finger chase 1.5 (left 2, right 1), nose-finger test 1.5 (left 2, right 1), fast alternating hand movements 1.0 (left 1, right 1) and heel-shin slide 2.0 (left 2, right 2)].

By WES we identified homozygous mutations of TTPA gene (c.473C>T, p.Phe185Ser) in a Chinese family with ARCA and we have excluded common causes of ataxia. AVED was first reported by Burck et al[8]. It usually manifests as a mild disease course and is rarely reported in China. The presentation of AVED is highly heterogeneous with onset usually in childhood[9] but some cases have manifested in infancy and in adulthood[1]. Clinical phenotypes include progressive gait ataxia, movement disorders, areflexia, dysarthria, epilepsy, pyramidal signs, impaired proprioception and vibration sense and sensory neuropathy[9-11]. Apart from cerebellar ataxia, our patient exhibited obvious head tremor. Head titubation, seen in 37% to 73% of patients, and cervical dystonia are distinguishing motor features of AVED[1,3,12]. Non-neurological symptoms, such as retinitis pigmentosa, macular degeneration and cardiomyopathy[13,14] were not found in our patient. Laboratory examination often reveals markedly low serum vitamin E concentration in AVED[1]. The patient’s MRI showed no obvious cerebellar atrophy in our patient and absence of cerebellar atrophy is common in AVED patients[15].

To date, various mutations of the TTPA gene have been reported[16]. The genotype-phenotype correlations were not found to be strong in AVED and c.744delA was the most frequent mutation, often originating in the Mediterranean region[9]. Moreover, 744delA could increase the risk of early age onset, severe disease course and cardiomyopathy[17]. c.473C>T(p.F185S), which was detected in our patient, has not been reported previously. Her symptoms began in adolescence and she is still able to walk 18 years after the onset of disease. F185S is located in CRAL_TRIO domain and its predicted function is to combine with α-tocopherol[18]. Bioinformatic analysis predicted this novel mutation would lead to the damage of protein function.

AVED is a treatable form of hereditary ataxia and early and sustained vitamin E supplementation could result in a remarkable clinical response or stabilization in AVED patients[1,19,20]. In patients with ataxia, a prompt investigation for vitamin E deficiency is recommended[19,20]. AVED patients require lifelong vitamin E supplementation at 300-2400 mg/d to maintain adequate plasma levels of vitamin E[1,8,14]. Our patient received 1200 mg/d of vitamin E for 2 years and her symptoms showed no deterioration.

We identified a Chinese AVED female patient caused by a novel mutation in the TTPA gene. This finding widens the known TTPA gene mutation spectrum.

We thank the patient who participated in our study and her family members.

| 1. | El Euch-Fayache G, Bouhlal Y, Amouri R, Feki M, Hentati F. Molecular, clinical and peripheral neuropathy study of Tunisian patients with ataxia with vitamin E deficiency. Brain. 2014;137:402-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hamza W, Ali Pacha L, Hamadouche T, Muller J, Drouot N, Ferrat F, Makri S, Chaouch M, Tazir M, Koenig M, Benhassine T. Molecular and clinical study of a cohort of 110 Algerian patients with autosomal recessive ataxia. BMC Med Genet. 2015;16:36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Benomar A, Yahyaoui M, Meggouh F, Bouhouche A, Boutchich M, Bouslam N, Zaim A, Schmitt M, Belaidi H, Ouazzani R, Chkili T, Koenig M. Clinical comparison between AVED patients with 744 del A mutation and Friedreich ataxia with GAA expansion in 15 Moroccan families. J Neurol Sci. 2002;198:25-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Esmer C, Salazar MA, Rentería PE, Bravo OA. Clinical and molecular findings in a patient with ataxia with vitamin E deficiency, homozygous for the c.205-1G>C mutation in the TTPA gene. Bol Med Hos Infant Mex. 2013;70:313-317. |

| 5. | Chung S, Ghelfi M, Atkinson J, Parker R, Qian J, Carlin C, Manor D. Vitamin E and Phosphoinositides Regulate the Intracellular Localization of the Hepatic α-Tocopherol Transfer Protein. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:17028-17039. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hao Y, Gu W, Wang G, Chen Y, Zhang J. Clinical and genetic study of ataxia with isolated vitamin E deficiency. Zhonghua Shenjingke Zazhi. 2014;47:90-95. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Kono S, Otsuji A, Hattori H, Shirakawa K, Suzuki H, Miyajima H. Ataxia with vitamin E deficiency with a mutation in a phospholipid transfer protein gene. J Neurol. 2009;256:1180-1181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Burck U, Goebel HH, Kuhlendahl HD, Meier C, Goebel KM. Neuromyopathy and vitamin E deficiency in man. Neuropediatrics. 1981;12:267-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Elkamil A, Johansen KK, Aasly J. Ataxia with vitamin e deficiency in norway. J Mov Disord. 2015;8:33-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Pearson TS. More Than Ataxia: Hyperkinetic Movement Disorders in Childhood Autosomal Recessive Ataxia Syndromes. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y). 2016;6:368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Müller KI, Bekkelund SI. Epilepsy in a patient with ataxia caused by vitamin E deficiency. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Becker AE, Vargas W, Pearson TS. Ataxia with Vitamin E Deficiency May Present with Cervical Dystonia. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y). 2016;6:374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Iwasa K, Shima K, Komai K, Nishida Y, Yokota T, Yamada M. Retinitis pigmentosa and macular degeneration in a patient with ataxia with isolated vitamin E deficiency with a novel c.717 del C mutation in the TTPA gene. J Neurol Sci. 2014;345:228-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mariotti C, Gellera C, Rimoldi M, Mineri R, Uziel G, Zorzi G, Pareyson D, Piccolo G, Gambi D, Piacentini S, Squitieri F, Capra R, Castellotti B, Di Donato S. Ataxia with isolated vitamin E deficiency: neurological phenotype, clinical follow-up and novel mutations in TTPA gene in Italian families. Neurol Sci. 2004;25:130-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Fogel BL, Perlman S. Clinical features and molecular genetics of autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxias. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:245-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Di Donato I, Bianchi S, Federico A. Ataxia with vitamin E deficiency: update of molecular diagnosis. Neurol Sci. 2010;31:511-515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Marzouki N, Benomar A, Yahyaoui M, Birouk N, Elouazzani M, Chkili T, Benlemlih M. Vitamin E deficiency ataxia with (744 del A) mutation on alpha-TTP gene: genetic and clinical peculiarities in Moroccan patients. Eur J Med Genet. 2005;48:21-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Min KC, Kovall RA, Hendrickson WA. Crystal structure of human alpha-tocopherol transfer protein bound to its ligand: implications for ataxia with vitamin E deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:14713-14718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kohlschütter A, Finckh B, Nickel M, Bley A, Hübner C. First Recognized Patient with Genetic Vitamin E Deficiency Stable after 36 Years of Controlled Supplement Therapy. Neurodegener Dis. 2020;20:35-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Schuelke M, Mayatepek E, Inter M, Becker M, Pfeiffer E, Speer A, Hübner C, Finckh B. Treatment of ataxia in isolated vitamin E deficiency caused by alpha-tocopherol transfer protein deficiency. J Pediatr. 1999;134:240-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Clinical neurology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Greco T, Italy; Kumar S, India S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Gong ZM