Published online Jul 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i21.7585

Peer-review started: February 18, 2022

First decision: March 24, 2022

Revised: April 19, 2022

Accepted: May 27, 2022

Article in press: May 27, 2022

Published online: July 26, 2022

Processing time: 142 Days and 17.2 Hours

Comamonas kerstersii (C. kerstersii) infections have considered as non-pathogenic to humans, however due to new techniques such as matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS), more cases have been identified.

This is the first report of a maternal patient with a C. kerstersii bacteremia following caesarean section. Due to the severity of the patient’s condition; high fever and rapidly progressing organ damage, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit. C. kerstersii was detected by metagenomic next-generation sequencing testing. Based on the drug sensitivity test, appropriate antibiotic treatment was given and the patient recovered fully.

This case report confirms that the detection via MALDI-TOF-MS and metage

Core Tip: Comamonas kerstersii (C. kerstersii) infections are rare and have been considered as non-pathogenic to humans. This is the first report of a maternal patient with a C. kerstersii bacteremia following caesarean section. The patient’s condition was critical with high fever and rapidly progressing organ damage and she was treated in the intensive care unit. C. kerstersii was detected by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight and metagenomic next-generation sequencing testing, which are reliable for the diagnosis of rare bacterial infections.

- Citation: Qu H, Zhao YH, Zhu WM, Liu L, Zhu M. Maternal peripartum bacteremia caused by intrauterine infection with Comamonas kerstersii: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(21): 7585-7591

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i21/7585.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i21.7585

Comamonas kerstersii (C. kerstersii) is an aerobic Gram-negative rod widely distributed in water, soil, and plants, and considered to be a non-pathogenic microorganism since its discovery in 2003[1]. However, this perception has changed since the first human infection caused by C. kerstersii was reported in 2013[2]. It can cause abscess formation, peritonitis, and septic shock, and to this day, 26 cases of C. kerstersii infections have been reported in the literature. Three of these cases were patients with bacteremia[3].

Research has shown that diagnosing C. kerstersii could be difficult and biased as records of phenotypic identification are lacking in databases[4,5]. Compared with the traditional isolation and culture methods, matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS)[6], and metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) detection provides a powerful means for the rapid isolation and unbiased correct identification of rare pathogenic bacteria during diagnosis and treatment[4,5,7]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case-report of a complicated maternal case of C. kerstersii bacteremia. Compared with several cases of severe C. kerstersii infection in recent years[7-10], besides abdominal pain and high fever, our patient also had intestinal obstruction, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, and pulmonary embolism. In this case report, we will discuss the clinical characteristics and analyze the unique complications associated with this case.

A 29-year-old woman was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), due to a critical condition including persistent high fever and signs of damage to multiple organs following caesarian section.

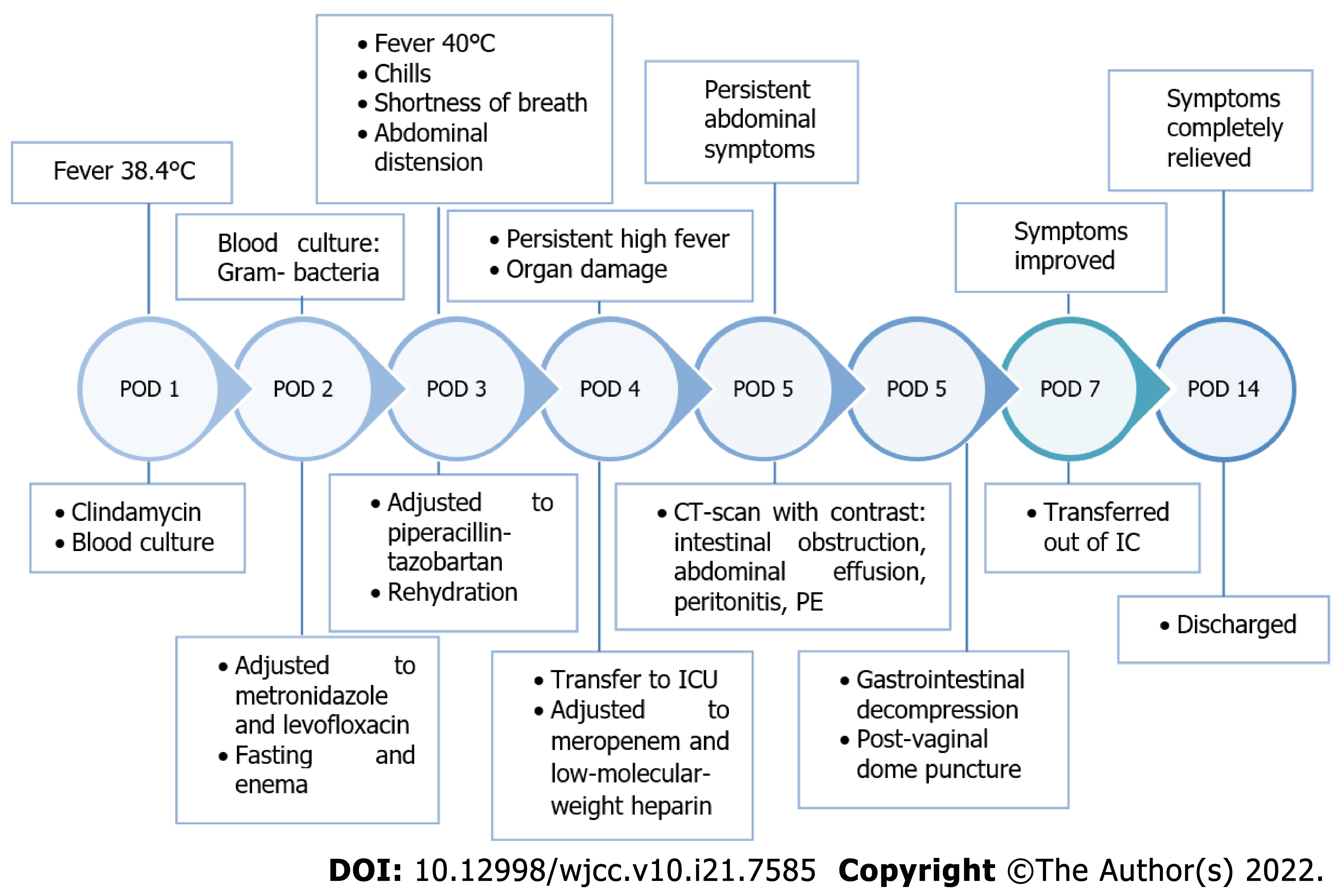

The patient, a 29-year-old woman with an obstetric history of G1 P0 A1 was diagnosed with pregnancy at 37 wk and 6 d, hip position, and labor admission. Her pregnancy was uncomplicated, however 3 d after admission, cesarean section was performed due to a breeched position of the fetus. The surgery was uneventful, performed with spinal anesthesia, and a healthy baby was delivered. One day after the surgery, the patient developed a fever with a peak body temperature of 38.4 °C. Figure 1 is a timeline of relevant events in which the symptoms, diagnostics, and treatment of the patient after admission are included.

The patient had a blank medical history without chronic diseases.

N/A.

Abdominal distension was noted; however, there was no substantial stomach discomfort. On the third day after surgery, the patient started having chills, shortness of breath, intermittent tingling on both sides of the lower abdomen, and abdominal distension. A temperature of 40 °C, heart rate of 115 beats/min, blood pressure of 147/84 mmHg, respiratory rate of 20 times/min, and oxygen saturation of 92% was measured.

Blood routine results showed 10.29 × 109/L white blood cells pre-admission (reference range: 4.5-11.0 × 109/L), and 14.83 × 109/L white blood cells with a differential white blood count of neutrophils 83.2%, and lymphocytes 9.9% upon admission on postoperative day 1. Other laboratory data were within the normal range. Because the presence of infection was highly suspected, blood cultures were obtained. However, no improvement in the symptoms was observed after antibiotic treatment. The blood routine test on the third day after surgery revealed white blood cells of 20.45 × 109/L and procalcitonin of 5.19 μg/L (reference range: 0-0.05 μg/L). Gram-negative bacteria were detected in the blood culture.

Because the patient had persistent abdominal symptoms, a computed tomography (CT)-scan with contrast was performed. The results showed multiple small intestine and colorectal expansion with intestinal obstruction, a small amount of abdominal and pelvic effusion and peritonitis, increased uterine volume, and an intermixed high and low intrauterine density. Shadow of a partial filling defect in the bilateral lower pulmonary artery was detected, which was suspect for pulmonary embolism.

In order to treat the intestinal obstruction, gastrointestinal decompression was performed, and a large amount of coffee-color liquid came out of the gastric tube. A post-vaginal dome puncture was per

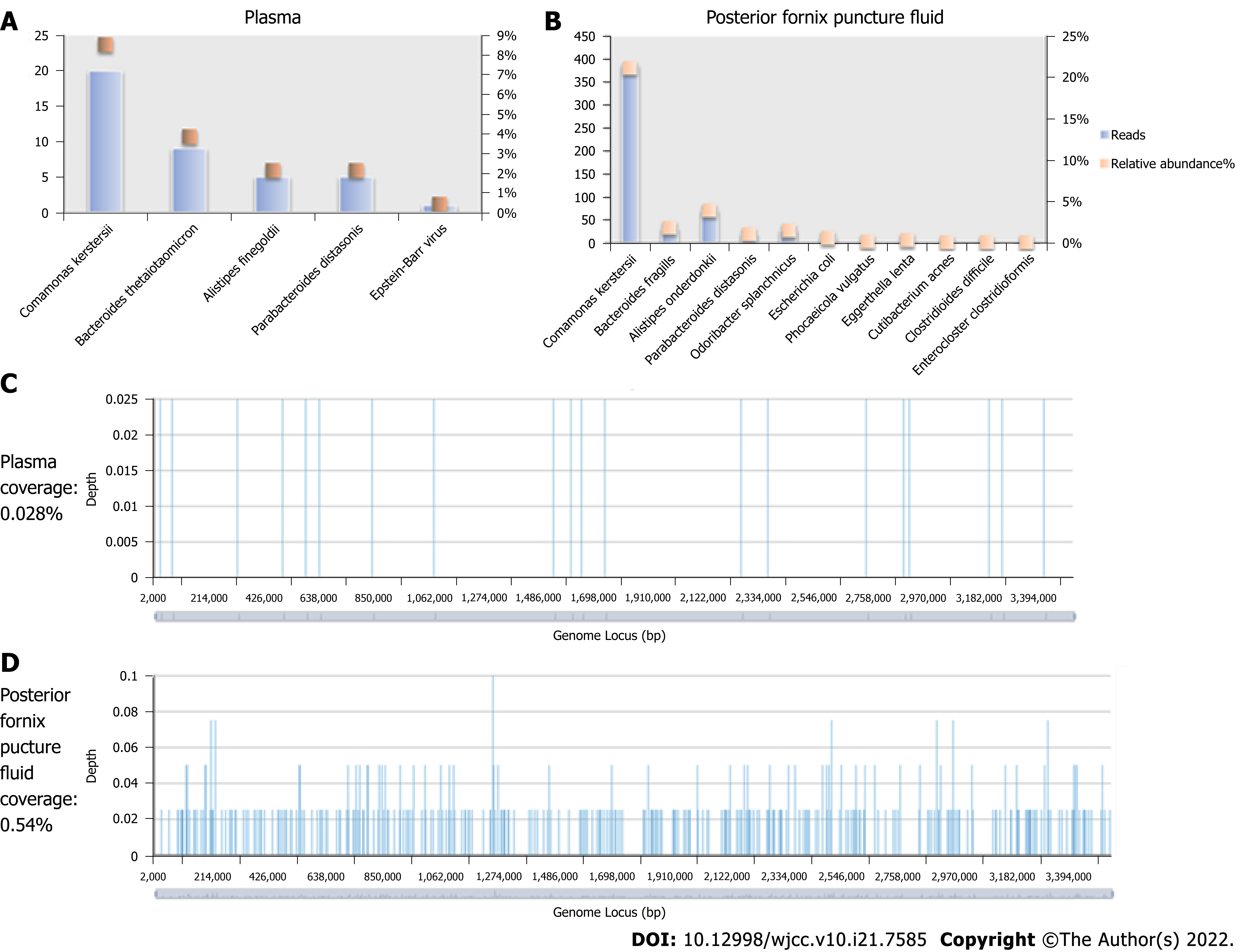

Peripheral blood was extracted, and two samples were sent for mNGS and microbial culture. mNGS of plasma and posterior fornix puncture fluid revealed C. kerstersii with reads of 20 and 386, respectively (Figure 2). The blood culture results further confirmed the mNGS results, suggesting that the patient did indeed have a C. kerstersii infection.

C. kerstersii was detected in the blood culture and mNGS testing.

Empirical iv treatment with 4 g of clindamycin was given for 2 d after initial symptoms; however, it did not alleviate the symptoms. Following the detection of Gram-negative bacteria in the blood culture, the antibiotic treatment was adjusted to metronidazole (250 mg qid) and levofloxacin (200 mg bid). The patient was also treated with fasting and enema, however it showed no improvement in abdominal distension. Comamonas was found in the blood culture after three days of fever, and the antibiotic was changed to piperacillin-tazobartan (4.5 g tid for 2 d) based on the drug sensitivity data. Rehydration was also given to support treatment.

The corresponding drug sensitivity is shown in Table 1. Due to the persistent high fever and signs of damage to multiple organs, the patient was transferred to the ICU, and the antibiotics were changed to meropenem (1.0 g tid). According to the drug sensitivity test, meropenem was continued and low-molecular-weight heparin (2000 IU ih bid) anticoagulant therapy was added to inhibit gastric acid secretion and protect the gastric mucosa.

| Antibiotics | MIC mg/L | Susceptibility |

| Cefotaxime | 0.25 | S |

| Meropenem | 0.25 | S |

| Piperacillin-tazobartan | 0.25 | S |

| Ceftazidime | 1 | S |

| Ciprofloxacin | 4 | R |

| Gentamycin | 8 | I |

| Aztreonam | 16 | I |

| SMZ-TMP | > 32 | R |

| Cefepime | 0.5 | S |

After treatment in the ICU, the patient’s body temperature, respiratory rate, heart rate, and oxygenation of the lung returned to normal, gastrointestinal bleeding stopped, abdominal distension relieved, and gastrointestinal function recovered. After 4 d in the ICU, she was transferred back to the obstetrics department, and the symptoms were completely relieved after 7 d.

C. kerstersii is a Gram-negative bacterium widely distributed in nature. It was originally described in 2003 as one of the three genotypes, native from Comamonas terrigena[1]. For a long time, C. kerstersii has been considered to be non-pathogenic to humans[1]. However, since the first human infection of C. kerstersii was reported in 2013, more reports of C. kerstersii related infections have been emerging[2,3,5-12]. Thus far, 26 Cases of C. kerstersii have been reported in the literature, of which three were patients with bacteremia[3]. This has led to the speculation that previous C. kerstersii infections may have been missed or misdiagnosed as C. kerstersii is not found in most databases for the identification of bacteria[4,5]. This problem has been solved by using new techniques in microbiology, such as MALDI-TOF-MS. By using mass spectrometry common as well as uncommon bacterial species can be accurately identified within minutes[5,6].

Different from previous cases, we report for the first time a maternal postpartum case of C. kerstersii. The patient described in this case report, presented with obvious intestinal obstruction, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, and breathing difficulties. As such, the presence of a lower pulmonary artery embolism was also confirmed by CT, in addition to the typical symptoms of abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and fever. This is a unique case that has not been described in previous case reports. In addition to the former, the patient also developed significant hypernatremia at the stage of persistent high fever, however she did not show any symptoms of dehydration, and blood sodium levels were rapidly restored following normalization of body temperature. We cannot clarify yet whether the changes have a specific relationship with the infection. We hypothesize it could be due to intestinal obstruction and decompression by gastrointestinal loss of fluid. Since the patient started developing fever, clindamycin, levofloxacin, metronidazole, piperacillin-tazobartan, and meropenem were given as antibiotic treatment. A blood culture obtained on admission revealed the diagnosis of C. kerstersii. Although the drug sensitivity test confirmed that C. kerstersii was sensitive to a broad range of antimicrobial drugs, the antibiotics given in the early stage of the disease did not effectively control the development of the disease. The condition of the patient only started improving after the use of meropenem.

Previous reports have shown a clear association between C. kerstersii and peritonitis resulting from diverticulosis, pelvic peritonitis, a perforated appendix, and bacteraemia [2,7,8,12,13]. Furthermore, an uncommon case of a 5-year-old girl with urinary tract infection caused by C. kerstersii has been published in 2018[9]. There is even one report of C. kerstersii infection resulting from contact with contaminated fish tank water, in which the patient fully recovered with levofloxacin[11]. The newest case report involving C. kerstersii infection is from March 2022. The prescribed case is unusual since the patient neither had predisposing conditions for his bacteremia, nor abdominal symptoms, except for recent constipation[14]. Although some strains are resistant to cephalosporins, the reports that have been discussed indicate excellent treatability with antibiotics and an optimistic prognosis following infection[15].

To clarify the source of the bacteria, we carefully monitored and reviewed the whole treatment process and environmental safety, and found no potential source of infection due to external factors. Literature has indicated that C. kerstersii exists in the intestines of healthy people and could cause infection under specific conditions[11]. Therefore, we speculate that the onset of this case was related to abdominal irritation and translocation of colonized bacteria after cesarean section. This has been suggested by Opota et al[7] as well, who reported a patient with mixed C. kerstersii and Bacteroides fragilis bacteremia in the presence of diverticulosis. They suggested that translocation of C. kerstersii from the gut was the source of infections. A C. kerstersii infection is rare in clinical practice. In the identification of the bacterial cultures, we isolated the bacteria early with the MALDI-TOF-MS method, and confirmed the diagnosis by mNGS. Both assay methods provided rapid, accurate, and unbiased results.

This is the first report of maternal case of C. kerstersii bacteremia. Unlike previously reported cases, this patient developed a series of severe manifestations including intestinal obstruction, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, pulmonary embolism, hypernatremia, and rapidly progressing organ damage. Routine antibiotic treatment did not effectively treat her condition and improvement occurred only after giving meropenem, suggesting that the pathogenic force of C. kerstersii may be much higher than previous understanding. The detection via MALDI-TOF-MS and mNGS provides a reliable basis for the diagnosis of this rare bacterial infection. Early diagnosis and multidisciplinary intervention are essential.

| 1. | Wauters G, De Baere T, Willems A, Falsen E, Vaneechoutte M. Description of Comamonas aquatica comb. nov. and Comamonas kerstersii sp. nov. for two subgroups of Comamonas terrigena and emended description of Comamonas terrigena. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2003;53:859-862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Almuzara MN, Cittadini R, Vera Ocampo C, Bakai R, Traglia G, Ramirez MS, del Castillo M, Vay CA. Intra-abdominal infections due to Comamonas kerstersii. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:1998-2000. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Liu XJ, Qiao XW, Huang TM, Li L, Jiang SP. Comamonas kerstersii bacteremia. Med Mal Infect. 2020;50:288-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jiang X, Liu W, Zheng B. Complete genome sequencing of Comamonas kerstersii 8943, a causative agent for peritonitis. Sci Data. 2018;5:180222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhou YH, Ma HX, Dong ZY, Shen MH. Comamonas kerstersii bacteremia in a patient with acute perforated appendicitis: A rare case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e9296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Almuzara M, Barberis C, Traglia G, Famiglietti A, Ramirez MS, Vay C. Evaluation of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time-of-flight mass spectrometry for species identification of nonfermenting Gram-negative bacilli. J Microbiol Methods. 2015;112:24-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Opota O, Ney B, Zanetti G, Jaton K, Greub G, Prod'hom G. Bacteremia caused by Comamonas kerstersii in a patient with diverticulosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:1009-1012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Biswas JS, Fitchett J, O'Hara G. Comamonas kerstersii and the perforated appendix. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:3134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Almuzara M, Cittadini R, Estraviz ML, Ellis A, Vay C. First report of Comamonas kerstersii causing urinary tract infection. New Microbes New Infect. 2018;24:4-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Almuzara M, Barberis C, Veiga F, Bakai R, Cittadini R, Vera Ocampo C, Alonso Serena M, Cohen E, Ramirez MS, Famiglietti A, Stecher D, Del Castillo M, Vay C. Unusual presentations of Comamonas kerstersii infection. New Microbes New Infect. 2017;19:91-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Smith MD, Gradon JD. Bacteremia due to Comamonas species possibly associated with exposure to tropical fish. South Med J. 2003;96:815-817. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Farfán-Cano G, Parra-Vera H, Ávila-Choez A, Silva-Rojas G, Farfán-Cano S. [First identification in Ecuador of Comamonas kerstersii as an infectious agent]. Rev Chilena Infectol. 2020;37:179-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Palacio R, Cornejo C, Seija V. Comamonas kerstersii. Rev Chilena Infectol. 2020;37:147-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rong K, Delport J, AlMutawa F. Comamonas kerstersii Bacteremia of Unknown Origin. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2022;2022:1129832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Moser AI, Campos-Madueno EI, Keller PM, Endimiani A. Complete Genome Sequence of a Third- and Fourth-Generation Cephalosporin-Resistant Comamonas kerstersii Isolate. Microbiol Resour Announc. 2021;10:e0039121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Infectious diseases

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Sharaf MM, Syria; Weerasinghe KD, Sri Lanka A-Editor: Liu X, China S-Editor: Chang KL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Chang KL