Published online Jun 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i18.6091

Peer-review started: December 29, 2021

First decision: January 25, 2022

Revised: February 14, 2022

Accepted: April 30, 2022

Article in press: April 30, 2022

Published online: June 26, 2022

Processing time: 169 Days and 12.8 Hours

Adalimumab (ADA) and infliximab (IFX) are the cornerstones of the treatment of Crohn’s disease (CD). It remains controversial whether there is a difference in the effectiveness and safety between IFX and ADA for CD.

To perform a meta-analysis to compare the effectiveness and safety of ADA and IFX in CD.

PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science databases were searched. Cohort studies were considered for inclusion. The primary outcomes were induction of response and remission, maintenance of response and remission, and secondary loss of response. Adverse events were secondary outcomes.

Fourteen cohort studies were included. There was no apparent difference between the two agents in the induction response [odds ratio (OR): 1.27, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.93-1.74, P = 0.14] and remission (OR: 1.11, 95%CI: 0.78–1.57, P = 0.57), maintenance response (OR: 1.08, 95%CI: 0.76–1.53, P = 0.67) and remission (OR: 1.26, 95%CI: 0.87–1.82, P = 0.22), and secondary loss of response (OR: 1.01, 95%CI: 0.65–1.55, P = 0.97). Subgroup analysis revealed ADA and IFX had similar rates of response, remission, and loss of response either in anti-tumor necrosis factor-α naïve or non-naïve patients. Further, there was a similar result regardless of whether CD patients were treated with optimized therapy, including dose intensification, shortening interval, and combination immunomodulators. However, ADA had a fewer overall adverse events than IFX (OR: 0.62, 95%CI: 0.42–0.91, P = 0.02).

ADA and IFX have similar clinical benefits for anti-tumor necrosis factor-α naïve or non-naïve CD patients. Overall adverse events rate is higher in patients in the IFX group.

Core Tip: Differences in immunogenicity and route of administration among adalimumab (ADA) and infliximab (IFX) allow for potential variability in therapeutic properties and efficacy. However, clear recommendations have been limited due to a lack of head-to-head comparison. We conducted a meta-analysis to synthesize current results and compared the efficacy and safety of ADA and IFX. The results showed that both have similar clinical benefits for anti-tumor necrosis factor-α naïve or non-naïve Crohn’s disease patients. Overall adverse events rate is higher in patients in the IFX group. ADA and IFX can be selected based on a possible history of adverse events and patient compliance.

- Citation: Yang HH, Huang Y, Zhou XC, Wang RN. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in comparison to infliximab for Crohn's disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(18): 6091-6104

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i18/6091.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i18.6091

Crohn's disease (CD) is an incurable chronic progressive condition characterized by abdominal pain, diarrhea, and weight loss. Aminosalicylic acid preparations, glucocorticoids, immunosuppressants, and biological agents have been used for treatment. Of these, biological agents are most widely used, especially anti-tumor necrosis factor-α (anti-TNF-α) blockers, including infliximab (IFX) and adalimumab (ADA). They all have been proven effective in inducing and maintaining remission and are routinely used in the treatment of CD[1,2]. We do not know, however, which treatment should be considered the priority?

IFX, a chimeric monoclonal antibody against TNF-α, is the first approved anti-TNF-α for moderate to severe CD. ADA is a humanized monoclonal antibody against TNF-α. IFX is given by intravenous infusion every 8 wk, whereas ADA is administered subcutaneously every 4 wk. Differences in immunogenicity and route of administration among them allow for potential variability in therapeutic properties and efficacy. However, clear recommendations have been limited due to a lack of head-to-head treatment comparison. A network meta-analysis published in 2014 found that ADA may be the most efficacious agent for maintenance of remission in CD in biologic-naïve patients[3], while many new clinical practice experience studies have shown their effectiveness and safety data were comparable. Furthermore, even though there has been cumulative research, few studies have focused on secondary loss of response, anti-TNF naïve or non-naïve patients, and the benefits of treatment optimization, such as dose intensification, shortening interval, and combination with immunomodulators. We performed a meta-analysis to synthesize these results and compared the efficacy and safety of ADA and IFX.

Our protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD: 42021191655). We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for the Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis guidelines.

We performed literature search of electronic sources, including PubMed, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and Embase, from initiation until October 31, 2020. No language restrictions were applied. The search terms included “Crohn disease,” “adalimumab”, and “infliximab” as Medical Subject Headings terms and their entry terms (Crohn disease: Crohn*; ileitis. Adalimumab: Humira; Exemptia. Infliximab: Remicade) to improve search outcomes. We also screened references of relevant articles to avoid omissions.

We included cohort studies comparing ADA and IFX for treating adults with CD. Comparisons of induction of remission and response rates, maintenance of remission and response rates, secondary loss of response rates, and the incidence of adverse events were among the outcomes of included studies. Excluded studies included those conducted in the pediatric population, those that did not investigate patients with inflammatory bowel disease, and those that did not report any outcomes of interest.

Two investigators (Yang HH and Huang Y) independently screened the titles, abstracts, and full texts of all papers to determine trial eligibility for inclusion. Investigators used a consensual approach to determine the inclusion or exclusion of selected studies after full-text assessment. Any disagreement was resolved through discussion or with a third researcher. The study characteristics were extracted independently by two authors using a standardized datasheet.

We collected the following variables: First author’s name, year of publication, country or area, study design, number of patients, gender, median age, Montreal classification, duration of follow-up, previous treatment, and outcomes of interest. The endpoint of this meta-analysis mainly included the induction response and remission, maintenance response and remission, overall adverse events rate, severe adverse events rate, and the rate of opportunistic infections.

The outcomes of interest included: (1) Induction of clinical remission defined as Crohn’s disease activity index (CDAI) < 150, Harvey Bradshaw Index (HBI) ≤ 4, or by physician's global assessment after ≤ 14 wk; (2) Induction of clinical response was defined as ΔCDAI ≥ 70, ΔHBI ≥ 2, or by physician's global assessment after ≤ 14 wk; (3) Maintenance of remission referred to clinical remission after ≤ 54 wk; (4) Maintenance of response referred to clinical response after ≤ 54 wk; (5) Secondary loss of response was defined as a reappearance of disease activity after achieving induction response, coupled with the need to change treatment, including dose intensification, the addition of an immunomodulator, or need to discontinue treatment; and (6) Secondary outcomes included a comparison of the incidence of overall adverse events, severe adverse events, and opportunistic infections in trials of maintenance therapy.

One author assessed the quality of included studies through the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS). High-quality studies were defined by a total score of ≥ 6.

RevMan 5.3 and Stata 16.0 software were used for statistical analysis. Odds ratio (OR) and concomitant 95% confidence interval (CI) were evaluated for the quantitative analyses. The random-effect model was used. Heterogeneity was explored by calculating I2 and employing the Q test. An I2 estimate > 50% and a P < 0.05 were regarded markers of significant heterogeneity, and its causes were investigated. We performed sensitivity analyses and subgroup analyses to detect the source of heterogeneity. P < 0.05 was considered to indicate a significant difference. Subgroup analyses were conducted based on the following grouping criteria: (1) Studies evaluating outcomes on anti-TNF naïve patients vs studies on non-naïve patients; (2) Studies evaluating outcomes on more perianal diseases in IFX group vs equal perianal disease in IFX and ADA group; (3) Studies evaluating primary outcomes given with treatment optimization, i.e. shortening the administration intervals, increasing the dose, and/or combination with immunomodulator therapy; and (4) Studies evaluating secondary outcomes at ≤ 48 wk vs > 48 wk. Funnel plots and Egger’s test was used to test for publication bias.

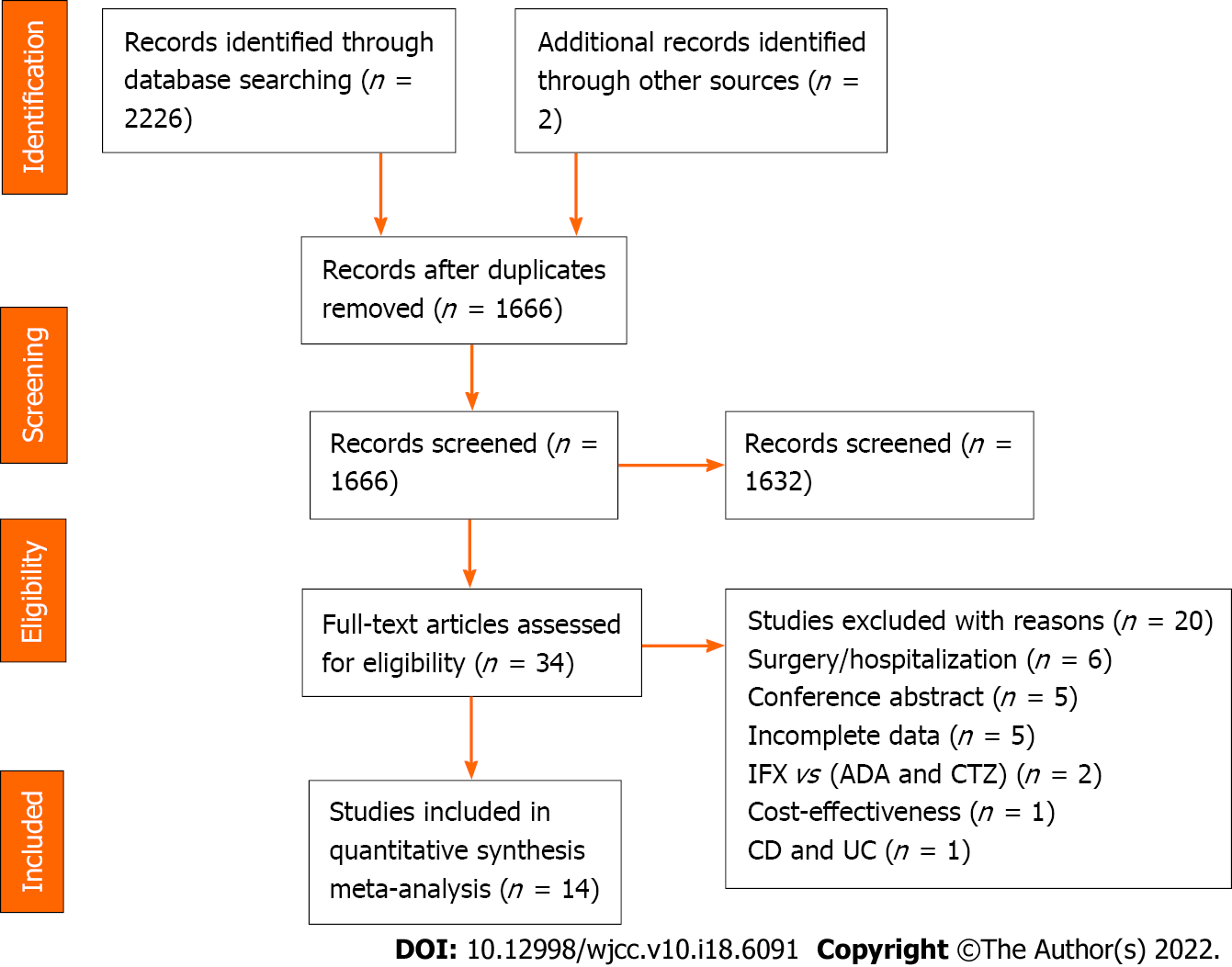

A preliminary search of the above database identified 2228 documents. Of these, we removed 562 duplicates, discarded 1632 studies after screening the titles and abstracts, and assessed the full text of 34 studies for eligibility. Finally, 14 cohort studies were included, and 20 were excluded. The flow diagram describes this process in detail (Figure 1).

Study design, outcomes, the definition of outcomes, inclusion criteria, and follow-up time differed among the included studies. Our meta-analysis consisted of two prospective cohort studies and 12 retrospective cohort studies. Three pieces of research evaluated maintenance response or remission at 54 wk[4-6], five at 48 wk[7-11], and one at 26 wk[12]. Regarding the definition of outcomes, most incorporated studies evaluated clinical response or remission by CDAI or HBI except for the study by Macaluso et al[10]. In addition, seven studies only included anti-TNF-naïve patients[4,7-9,12,13], and no study only included patients who failed anti-TNF treatment. Follow-up intervals across studies varied, ranging from 4 to 14 wk for induction period and 26 to 168 wk for maintenance period. The high NOS scores reflected the high quality of the enrolled studies. Thirteen studies got a score of ≥ 6, except for the study by Bau et al[14], which scored 5. Table 1 showed the overall characteristics of the selected studies.

| Ref. | Study design | Patientinclusion criteria | ADA/IFX, n | Definition of remission | Definition of secondary loss of response | Induction of response/remission in wk | Maintenance of response/remission in wk | Adverse events | NOS |

| Zorzi et al[6], 2012 | Retrospective | Active CD | 49/44 | CDAI < 150 | No improvement or worsening | 4/6 | 54 | Multiple | 6 |

| Kestens et al[4], 2013 | Retrospective | Naïve CD | 100/100 | NS | NS | NS | 54 | Multiple | 9 |

| Ma et al[17], 2014 | Retrospective | Naïve CD | 101/117 | NS | Requiring dose escalation | NS | NS | NS | 8 |

| Tursi et al[15], 2014 | Retrospective | CD | 67/59 | HBI ≤ 5 | NS | 6-14 | NS | Multiple | 8 |

| Cosnes et al[12], 2016 | Prospective | Naïve CD | 264/127 | CDAI < 150 | Disease activity | NS | 26 | Multiple | 8 |

| Varma et al[8], 2016 | Retrospective | Naïve CD | 18/63 | CDAI < 150 | NS | 12 | 48 | Multiple | 7 |

| Narula et al[9], 2016 | Prospective | Naïve CD | 111/251 | HBI < 5 | Dose escalation | 12 | 48 | Multiple | 8 |

| Bau et al[14], 2017 | Retrospective | Refractory CD | 62/68 | NS | NS | NS | 168 | Multiple | 5 |

| Otake et al[5], 2017 | Retrospective | CD | 29/39 | CDAI < 150 | Multiple | NS | 54 | NS | 8 |

| Doecke et al[16], 2017 | Retrospective | CD | 144/183 | CDAI ≤ 150 | NS | 14 | NS | NS | 7 |

| Benmassaoud et al[7], 2018 | Retrospective | Naïve CD | 77/143 | HBI ≤ 4 | Need for dose escalation | 12 | 48 | Multiple | 8 |

| Di Domenicantonio et al[13], 2018 | Retrospective | Naïve CD | 505/367 | NS | NS | NS | NS | Multiple | 9 |

| Macaluso et al[10], 2019 | Retrospective | Naïve and non-naïve CD | Naïve: 214/107; non-naïve: 47/47 | NS | NS | 12 | 48 | Multiple | 9 |

| Kaniewska et al[11], 2019 | Retrospective | CD | 95/82 | CDAI < 150 | NS | NS | 48 | Multiple | 7 |

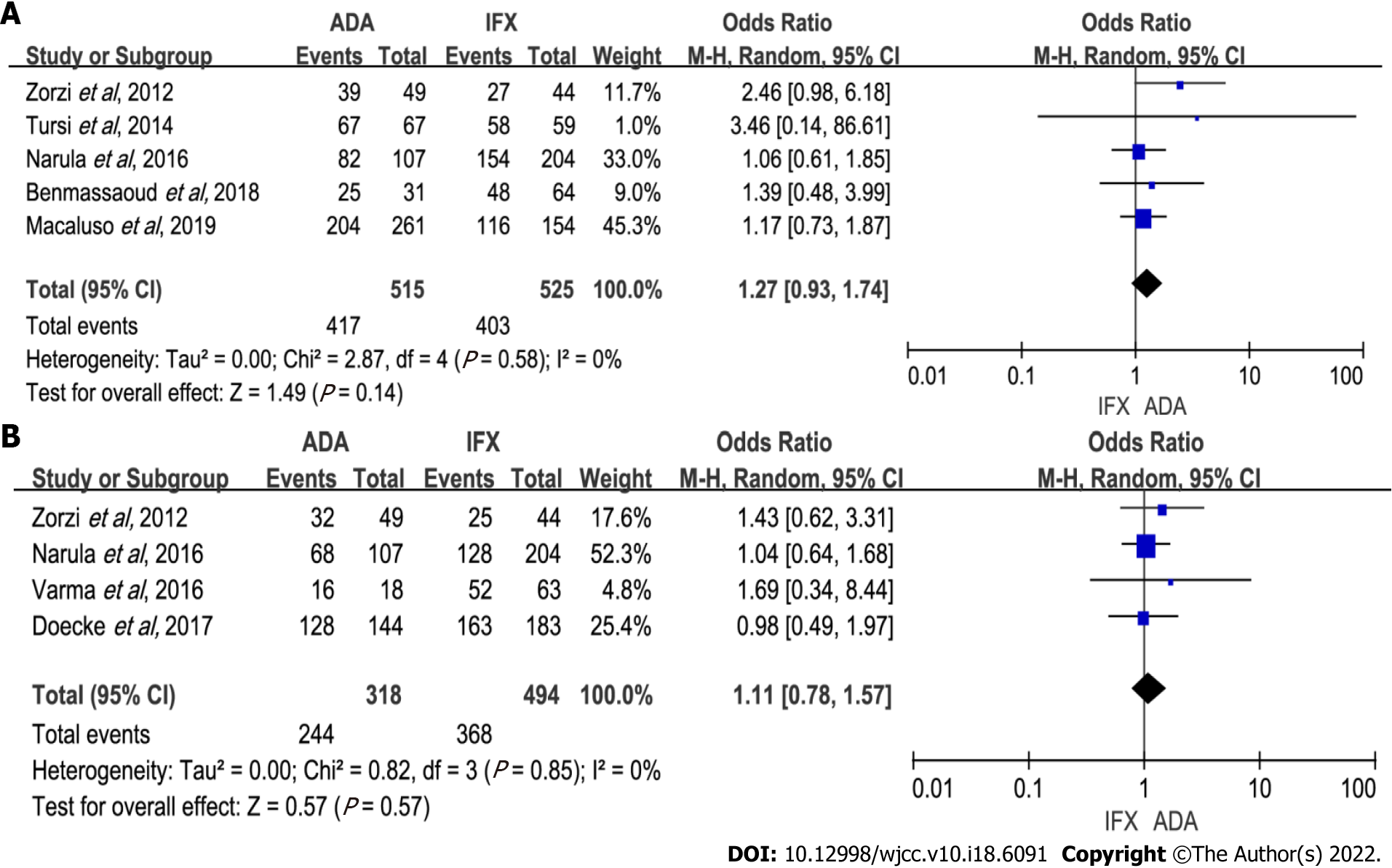

Induction of response: Five studies (1040 patients) recorded induction of response[6,7,9,10,15]. No difference was shown between groups in response rates (OR: 1.27, 95%CI: 0.93–1.74, P = 0.14). Of the 1040 patients in five studies, 515 received ADA therapy. The heterogeneity of those studies was insignificant (P = 0.58, I2 = 0%) (Figure 2A). Sensitivity analysis showed no significant changes to the exclusion of any one of the studies (Supplementary Table 1). Subgroup analysis revealed no remarkable difference between groups (Table 2).

| Outcomes of interest | Subgroup analysis | |||||||

| Grouping criteria | Categories | Studies, n | Patients, n | OR | 95%CI | I2, % | P value | |

| Induction of response | Anti-TNF naivety | Naïve | 3 | 727 | 1.17 | (0.80-1.70) | 0 | 0.41 |

| Non-naïve | 3 | 313 | 1.44 | (0.55-3.78) | 47 | 0.46 | ||

| Use optimization | Yes | 5 | 1040 | 1.27 | (0.93-1.74) | 0 | 0.14 | |

| No | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | ||

| Induction of remission | Anti-TNF naivety | Naïve | 2 | 392 | 1.08 | (0.68-0.72) | 0 | 0.75 |

| Non-naïve | 2 | 420 | 1.15 | (0.67-1.96) | 0 | 0.62 | ||

| Use optimization | Yes | 3 | 731 | 1.08 | (0.76-1.55) | 0 | 0.66 | |

| No | 1 | 81 | 1.69 | (0.34-8.44) | - | 0.52 | ||

| Maintenance of response | Anti-TNF naivety | Naïve | 5 | 1468 | 1.08 | (0.72-1.62) | 63 | 0.71 |

| Non-naïve | 3 | 354 | 1.10 | (0.64-1.90) | 0 | 0.73 | ||

| Use optimization | Yes | 6 | 1645 | 1.12 | (0.77-1.63) | 62 | 0.57 | |

| No | 1 | 177 | 0.64 | (0.18-2.29) | - | 0.50 | ||

| Maintenance of remission | Anti-TNF naivety | Naïve | 3 | 442 | 1.39 | (0.92-2.11) | 0 | 0.12 |

| Non-naïve | 3 | 328 | 1.24 | (0.56-2.72) | 53 | 0.59 | ||

| Use optimization | Yes | 3 | 458 | 1.41 | (0.95-2.09) | 0 | 0.09 | |

| No | 3 | 312 | 1.18 | (0.46-2.99) | 55 | 0.73 | ||

| Secondary loss of response | Anti-TNF naivety | Naïve | 3 | 353 | 1.09 | (0.54-2.18) | 42 | 0.81 |

| Non-naïve | 3 | 947 | 0.91 | (0.46-1.80) | 72 | 0.78 | ||

| Use optimization | Yes | 5 | 1247 | 1.07 | (0.69-1.67) | 56 | 0.75 | |

| No | 1 | 53 | 0.48 | (0.13-1.68) | 54 | 0.99 | ||

| Overall adverse events | Anti-TNF naivety | Naïve | 5 | 1184 | 0.67 | (0.50-0.89) | 1 | 0.005 |

| Non-naïve | 4 | 469 | 0.41 | (0.31-1.31) | 79 | 0.13 | ||

| Assessment time | ≤ 48 wk | 6 | 1323 | 0.50 | (0.33-0.76) | 41 | 0.001 | |

| > 48 wk | 2 | 330 | 1.00 | (0.62-1.60) | 0 | 0.98 | ||

| Severe adverse events | Anti-TNF naivety | Naïve | 3 | 1021 | 0.88 | (0.40-1.92) | 73 | 0.74 |

| Non-naïve | 4 | 526 | 0.45 | (0.03-6.51) | 81 | 0.56 | ||

| Assessment time | ≤ 48 wk | 4 | 746 | 1.32 | (0.80-2.19) | 0 | 0.28 | |

| > 48 wk | 3 | 801 | 0.52 | (0.09-3.05) | 80 | 0.47 | ||

| Opportunistic infections | Anti-TNF naivety | Naïve | 4 | 1654 | 0.78 | (0.54-1.14) | 0 | 0.21 |

| Non-naïve | 2 | 256 | 1.88 | (0.93-3.82) | 0 | 0.08 | ||

| Assessment time | ≤ 48 wk | 3 | 782 | 0.85 | (0.56-1.28) | 0 | 0.43 | |

| > 48 wk | 3 | 1128 | 1.12 | (0.38-3.24) | 57 | 0.84 | ||

Induction of remission: When combining all four studies[6,8,9,16] reporting induction of remission data (318 on ADA therapy and 494 on IFX therapy), we found no difference between the two groups of patients (OR: 1.11, 95%CI: 0.78–1.57, P = 0.57). Heterogeneity was low (P = 0.85, I2 = 0%) (Figure 2B). Subsequent subgroup analysis showed similar results (Table 2). In sensitivity analyses, excluding any one of the studies did not significantly impact the results (Supplementary Table 1).

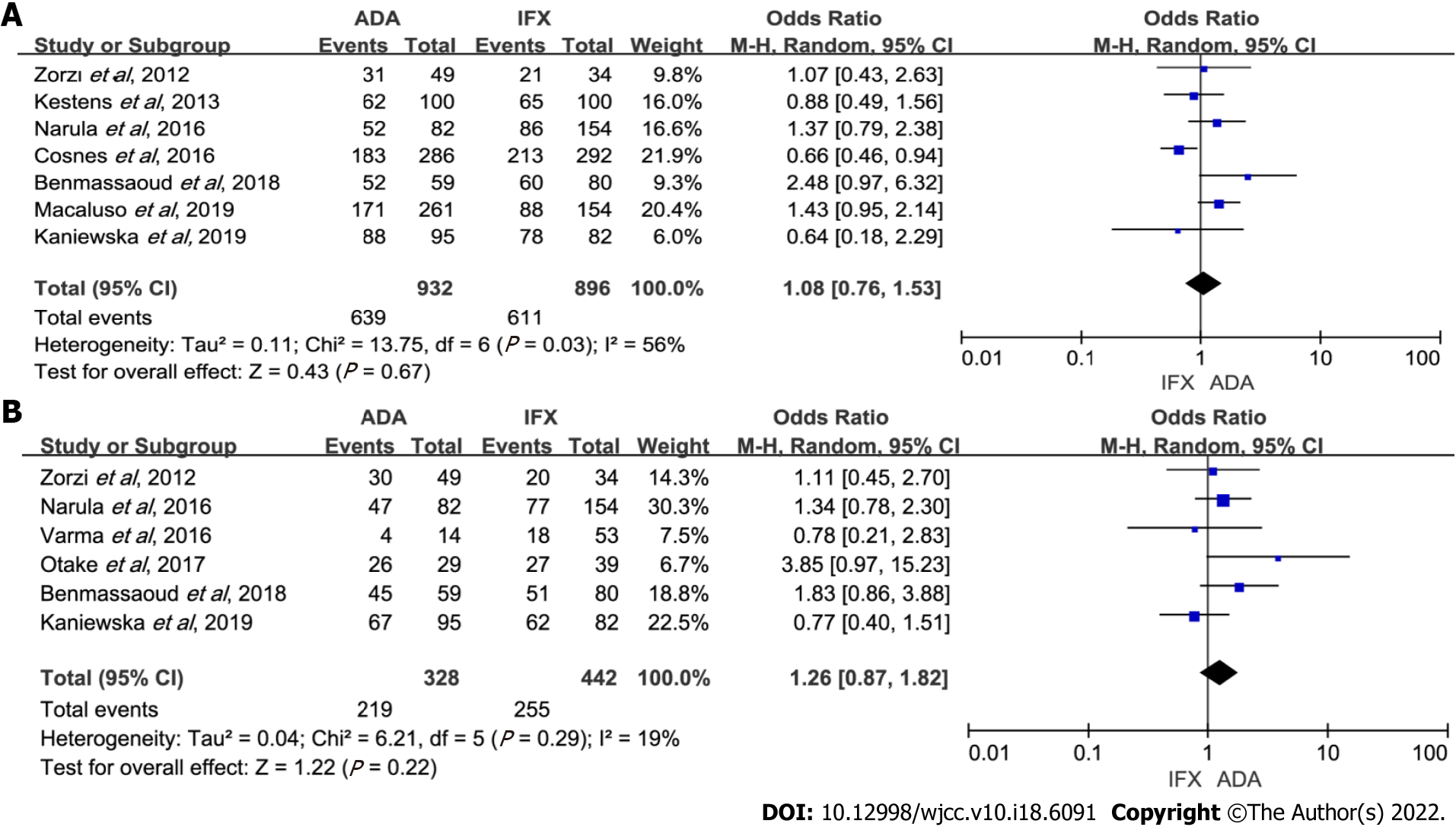

Maintenance of response: Of the 14 studies, seven reported the response rate in maintenance therapy[4,6,7,9-12]. A number of 1828 patients were included: 896 IFX-treated vs 932 ADA-treated. Data analysis showed that ADA and IFX had a similar rate of maintenance of response (OR: 1.08, 95%CI: 0.76–1.53, P = 0.67). Heterogeneity was significant (P = 0.03, I2 = 56%) (Figure 3A). Cosnes et al[12] evaluating response at 26 wk increased heterogeneity. In the sensitivity analysis, the result remained unchanged with the exclusion of any study (Supplementary Table 1). Subgroup analyses also showed no difference between the two groups (Table 2).

Maintenance of remission: There were 770 patients (328 on ADA therapy) available for analysis from six studies[5-9,11]. Data analysis showed that ADA and IFX had a similar rate of maintenance of remission (OR: 1.26, 95%CI: 0.87–1.82, P = 0.22). Heterogeneity was low (P = 0.29, I2 = 19%) (Figure 3B). Subgroup analyses also showed no statistical differences (Table 2). Sensitivity analysis indicated that the results were stable (Supplementary Table 1).

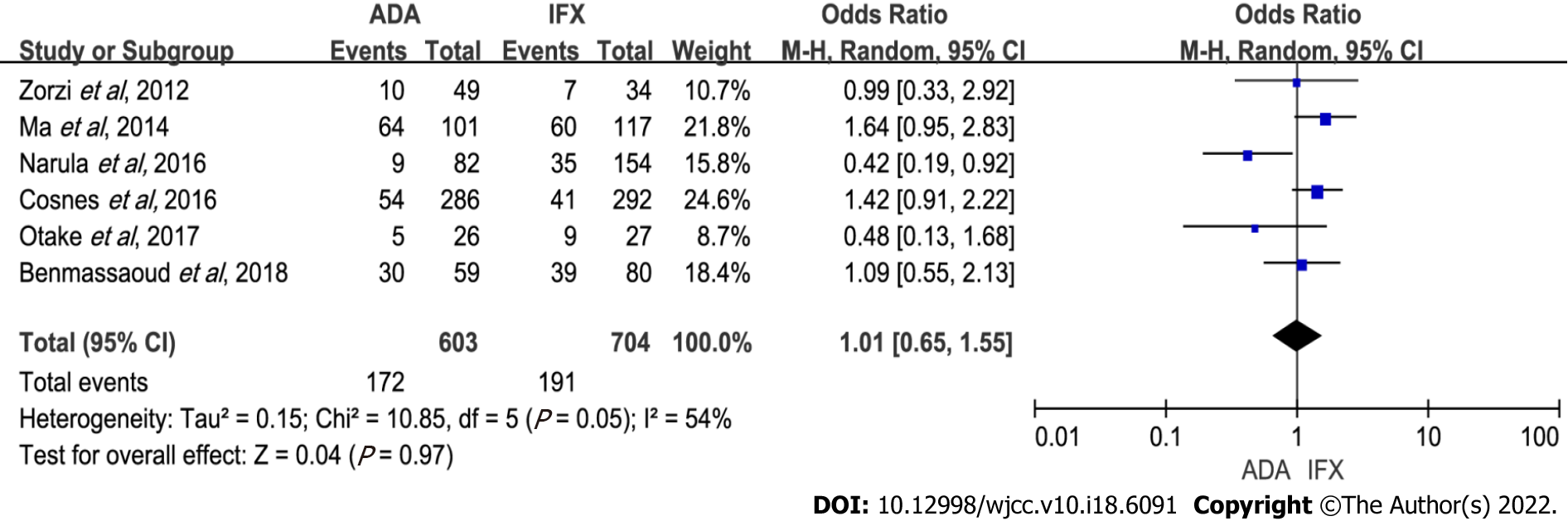

Secondary loss of response: Six studies with 1307 patients were included (603 receiving ADA and 704 IFX therapy)[5-7,9,12,17]. There was no statistical difference between the two treatments (OR: 1.01, 95%CI: 0.65–1.55, P = 0.97). Heterogeneity was notable (P = 0.05, I2 = 54%) (Figure 4). Heterogeneity was linked to the study by Narula et al[9], which found that IFX had more rate of loss of response than ADA. On sensitivity analyses, the results remained the same after excluding any one study (Supplementary Table 1). There was also no significant difference between ADA and IFX when subgroup analysis was done (Table 2).

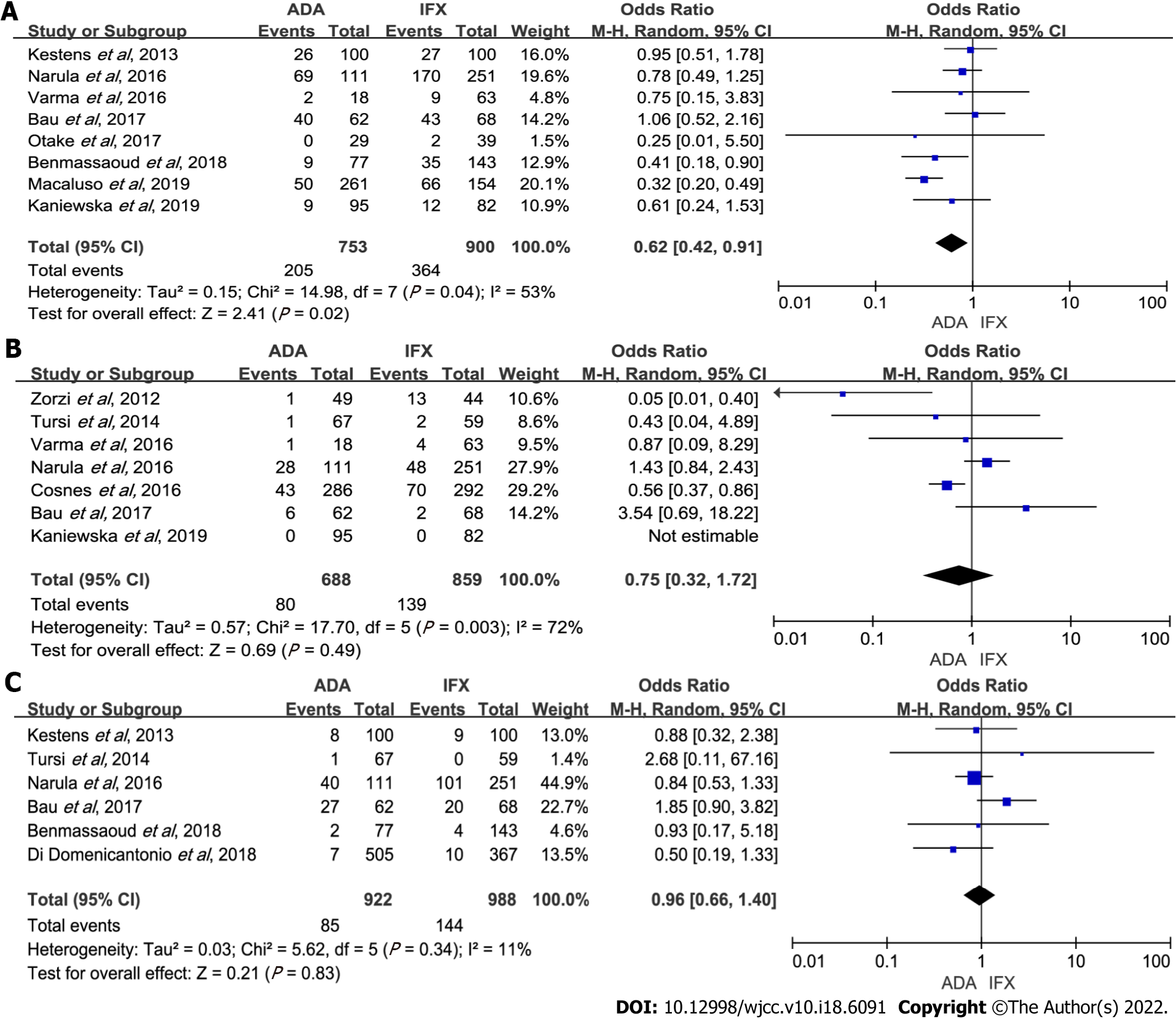

Overall adverse events: The incidence of overall adverse events was recorded in a total of eight cohort studies[4,5,7-11,14] that included 1653 patients, of which ADA was less than IFX (OR: 0.62, 95%CI: 0.42–0.91, P = 0.02). There was high heterogeneity (P = 0.04, I2 = 53%) (Figure 5A). Subgroup analysis revealed that ADA had fewer overall adverse events than IFX in ≤ 48 wk follow-up time (OR: 0.50, 95%CI: 0.33–0.76, P = 0.001); and in anti-TNF-α-naïve patients, IFX had more adverse events (OR: 0.67, 95%CI: 0.50–0.89, P = 0.005) (Table 2). Sensitivity analysis indicated that the results were slightly unstable (Supplementary Table 1).

Severe adverse events: Our analysis of seven studies[6,8,9,11,12,14,15] with a total of 1547 patients showed ADA had a similar rate of severe adverse events with IFX (OR: 0.75, 95%CI: 0.32–1.72, P = 0.49). Sensitivity analysis was performed due to notable heterogeneity (P = 0.003, I2 = 72%) (Figure 5B). Heterogeneity mainly originated from Zorzi et al[6] with more severe adverse events occurring in IFX therapy. The result remained unchanged with the exclusion of any study (Supplementary Table 1). Subgroup analysis also showed similar results (Table 2).

Opportunistic infections: Six studies[4,7,9,13-15] reported side effects, with a total number of 1910 cases (ADA: IFX = 922:988). Opportunistic infections rates in the IFX and ADA groups were similar (OR: 0.96, 95%CI: 0.66-1.40, P = 0.83), and no apparent heterogeneity was detected (Figure 5C). There was no significant difference when subgroup analysis was done (Table 2). Sensitivity analysis showed no significant changes when any one of the studies was excluded (Supplementary Table 1).

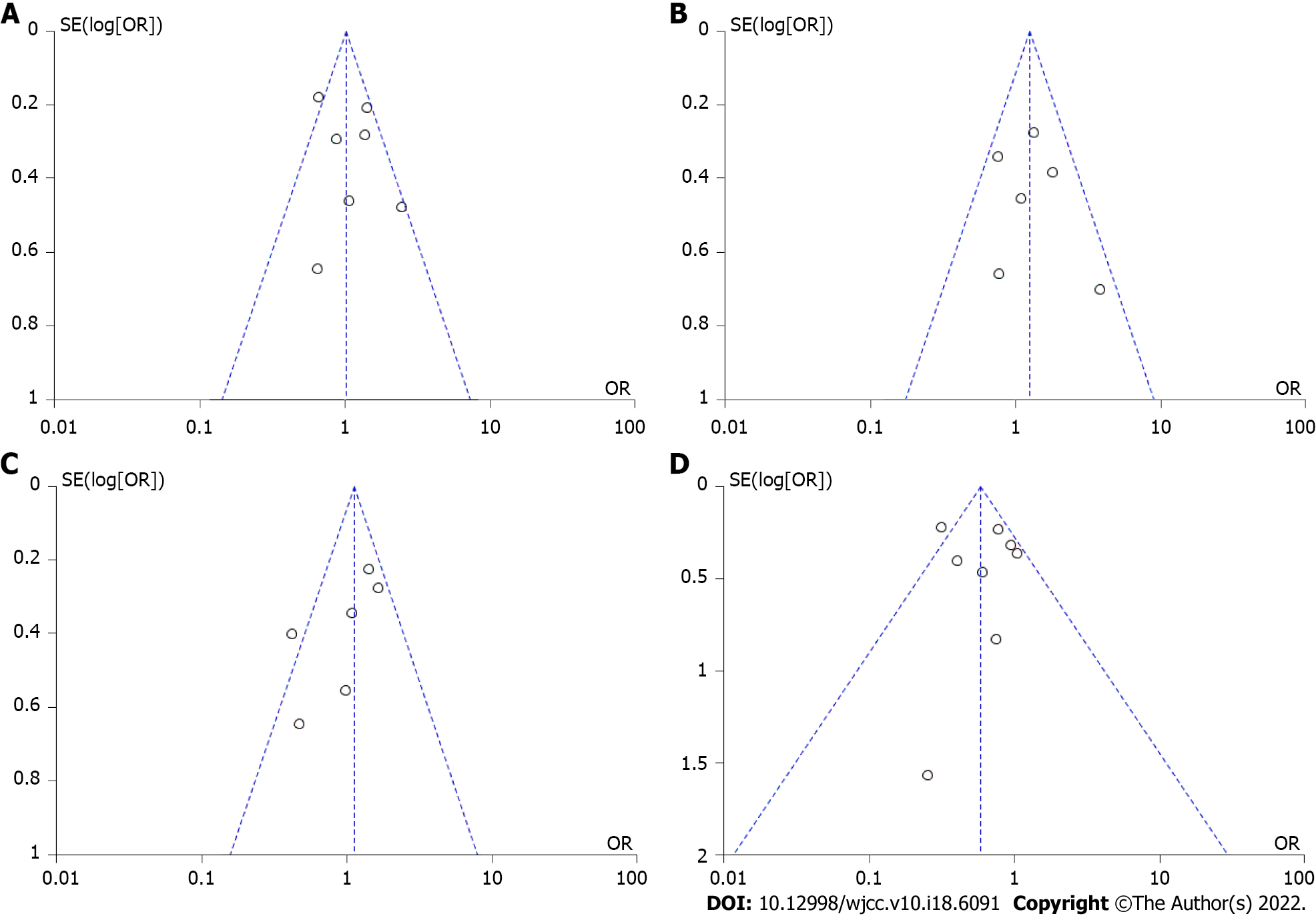

The symmetry of the funnel plot indicated there was no publication bias (Figure 6). The Egger’s test showed no significant publication bias for maintenance of response (P = 0.7024 > 0.05), maintenance of remission (P = 0.1003 > 0.05), secondary loss of response (P = 0.0510 > 0.05), and overall adverse events (P = 0.6717 > 0.05). GRADE evidence of all outcomes was judged as “low”. The results are shown in Table 3.

| Quality assessment-No. of studies | Quality assessment-study design | Quality assessment-risk of bias | Quality assessment-inconsistency | Quality assessment-indirectness | Quality assessment-imprecision | Quality assessment-Publication bias | Summary of findings-number of patient, with IFX | Summary of findings-number of patient, with ADA | Summary of findings-effect, relative (95%CI) | Summary of findings-effect, absolute (95%CI) | Summary of findings-effect, Quality |

| Induction of response | |||||||||||

| 5 | Observational study | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not found | 403/525 | 417/515 | OR: 1.27 (0.93-1.74) | 768 per 1000 | ⨁⨁◯◯ |

| Induction of remission | |||||||||||

| 4 | Observational study | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not found | 368/494 | 244/318 | OR: 1.11 (0.78-1.57) | 745 per 1000 | ⨁⨁◯◯ |

| Maintenance of response | |||||||||||

| 7 | Observational study | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not found | 611/896 | 639/932 | OR: 1.02 (0.83-1.25) | 682 per 1000 | ⨁⨁◯◯ |

| Maintenance of remission | |||||||||||

| 6 | Observational study | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not found | 255/442 | 219/328 | OR: 1.26 (0.87-1.82) | 577 per 1000 | ⨁⨁◯◯ |

| Secondary loss of response | |||||||||||

| 6 | Observational study | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not found | 191/704 | 172/603 | OR: 1.01 (0.65-1.55) | 271 per 1000 | ⨁⨁◯◯ |

| Overall adverse events | |||||||||||

| 8 | Observational study | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not found | 364/900 | 205/753 | OR: 0.62 (0.42-0.91) | 404 per 1000 | ⨁⨁◯◯ |

| Severe adverse events | |||||||||||

| 7 | Observational study | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not found | 139/859 | 80/688 | OR: 0.75 (0.32-1.72) | 162 per 1000 | ⨁⨁◯◯ |

| Opportunistic infection | |||||||||||

| 6 | Observational study | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not found | 144/988 | 85/922 | OR: 0.96 (0.66-1.40) | 146 per 1000 | ⨁⨁◯◯ |

The immunogenicity of anti-TNF-α agents triggered the formation of anti-drug antibodies (ADAbs) specific to the agent administered. ADAbs of IFX or ADA and reduced serum concentrations in association with ADAbs together lead to decreased clinical benefit and increased adverse events. Although the immunogenicity of IFX is usually higher than that for ADA, we found both of them have similar response characteristics in CD patients. In our meta-analyses, no significant differences in primary outcomes were found between groups treated with IFX and ADA. These results were consistent with the results of most published studies[5-12,15-17]. One unexpected finding was the extent to which the overall adverse events rate of IFX was higher than that of ADA. Our meta-analysis indicated that physicians may choose on an individual basis, according to a possible history of adverse events to either IFX or ADA and to patient compliance, to give either an intravenous infusion or a self-administered subcutaneous injection.

CD is a heterogeneous disease, and the therapeutic efficacy differs between the types of disease, e.g., location of disease, the existence of stenosis and/or fistula, or perianal involvement. There was no significant difference between IFX and ADA groups in the location of disease and existence of stenosis and/or fistula of included studies. However, IFX patients had more perianal diseases in the studies of Benmassaoud et al[7], Varma et al[8], Narula et al[9], and Cosnes et al[12]. Clinicians tended to choose IFX over ADA in patients with more severe disease activity or phenotypes (perianal disease) due to its intravenous administration and weight-based dosing schedule. We attempted to adjust for these differences through subgroup analysis, which led to the same conclusions (SupplementaryTables 2 and 3). Additionally, Ji et al[18] found the cumulative rate of nonrecurrence or aggravation of fistula at 24 mo was not significantly different between IFX and ADA groups (62.5% vs 83.9%, P = 0.09). Current evidence suggested that IFX and ADA had similar effects in patients with perianal disease.

Biologic-naïve or non-naïve patients were important factors to influence the results. It is controversial whether ADA had similar efficacy to IFX in previous anti-TNF exposure CD patients. Macaluso et al[10] compared clinical benefits between IFX and ADA only in biologic non-naïve CD patients and reported that there was no difference in clinical benefits at 12 wk and after 1 year (P = 0.600 and P = 0.620, respectively). A retrospective case-control study[19] found that the risk for ADAbs to IFX was higher than ADAbs to ADA when patients had prior antibodies to anti-TNF. They did not investigate clinical efficacy. However, Sasson and Ananthakrishnan[20] found that patients with high ADAbs titers exhibited similar rates of clinical efficacy to ADA therapy compared to those with low titers (at 3 mo and 12 mo P = 0.81 and 0.62 respectively). This may mean IFX and ADA have similar efficacy in previous anti-TNF exposed CD patients. Our findings indicated that either in naïve or non-naïve patients ADA and IFX had similar clinical response and remission. More studies conducted on previous anti-TNF exposure CD patients will be necessary.

Co-immunosuppression affected the results of the analysis. The finding that combination therapy with an immunomodulator is superior with IFX but not with ADA was reported in Kestens et al[4], Benmassaoud et al[7], and Doecke et al[16]. The possible reason is that IFX combined with immunomodulator treatment reduces its immunogenicity. However, clinical efficacy of ADA combination therapy did not differ from that of ADA monotherapy (71.8% vs 68.1% at week 26, P = 0.63)[21]. Therefore, more patients in the IFX group were combined with immunomodulator treatment than in the ADA group in the Narula et al[9] study. No change was found in results after sensitivity analysis was conducted. Patients were on concomitant immunomodulation at anti-TNF induction to improve the efficacy of the induction of the remission and discontinued co-therapy due to adverse effects or intolerability (from the beginning). When loss of response occurred, concomitant therapy was resumed (later add on). Only the Cosnes et al[12] study used immunomodulators later. No different results were found after sensitivity analysis was performed. Furthermore, CD patients who lost response were allowed to shorten intervals and double dosage. These optimization strategies also impacted the results. We conducted subgroup analyses comparing the outcomes between using dose optimization and not and found the clinical effect of ADA was similar to IFX.

Similar to the findings of many studies[4,10,17], the significantly higher rate of overall adverse events can be seen in patients using IFX, which could be attributed to infusion or allergic reactions. Benmassaoud et al[7] reported that IFX group patients were more likely to have infusion or injection reactions than ADA. A higher rate of allergic reactions in the IFX was observed in a study by Narula et al[9]. However, we noted that the difference did not exist in anti-TNF-α non-naïve patients and with long follow-up time. We were unable to evaluate long-term safety due to the different follow-up times of each study. Larger and long-term comparison studies will be necessary. In addition, the instability of the results also require further studies to establish these findings.

Additionally, we failed to evaluate long-term results due to the different follow-up times of each study. Inokuchi et al[22] performed a retrospective study to evaluate long-term prognosis. They observed that the rates of cumulative steroid-free remission rates and surgery-free did not differ significantly between the two groups after a median observation period of 64.2 mo (P = 0.42 and P = 0.74, respectively). The goal of CD treatment requires more than clinical healing. Mucosal healing and tissue healing are expected to stop disease progression and reduce recurrence. Tursi et al[15] found that mucosal healing and histological healing were comparable between the two groups (P = 0.946 and P = 0.895, respectively).

Although biologic agents targeting TNF-α have achieved remarkable progress in treating CD, some patients do not respond to the induction therapy or lose response over time (secondary loss of response). The anti-drug antibodies or low serum drug concentrations play a critical part in the loss of response[23]. If ADA is superior to IFX for remission, ADA should have a lower rate of secondary loss of response than IFX. However, we failed to find a difference in the secondary loss of response between the two groups, which contradicted our hypothesis. It was further demonstrated that both have similar effects.

This work is the first direct comparison meta-analysis to evaluate the comparative effectiveness and safety of ADA and IFX in CD. Previous network meta-analyses addressed similar outcomes in the Bayesian setting indirect comparison. In our study, we enrolled comparative trial data resulting in more credible results. Furthermore, head-to-head clinical trials comparing ADA and IFX would not be feasible in the future; therefore, our studies will help guide optimal therapies.

Our current study has some limitations. First, we only included observational studies and failed to control adequately confounders, such as disease severity, disease phenotype, steroid use, etc. In addition to clinical benefits, we should consider other factors, such as patients’ preferences and costs. Future studies are needed to address these questions.

IFX and ADA have similar response characteristics either in anti-TNF naïve and non-naïve CD patients, and ADA therapy has fewer overall adverse events. Our study indicates that IFX or ADA can be freely chosen as treatment based on physician and patient agreement. Eventually, the decision of which treatment to start may depend on factors such as patient preference and cost.

Infliximab (IFX) is often selected as the first-line anti-tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) agent for Crohn’s disease (CD), despite the lack of data showing its superiority over adalimumab (ADA).

By comparing the effectiveness and safety between ADA and IFX, we wanted to determine if IFX or ADA is superior to the other for treatment of CD.

The present meta-analysis was performed to evaluate the comparative effectiveness and safety of ADA and IFX for CD to assist clinicians in making treatment choices.

The clinical studies that compared the effectiveness or safety of ADA and IFX in the treatment of CD were searched in PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science databases.

Our meta-analysis of CD patients who were naïve or non-naïve to anti-TNF-α agents found no significant differences between IFX and ADA on many measures of effectiveness, including clinical response, clinical remission, and secondary loss of response. Interestingly, we observed a higher rate of overall adverse events in patients using IFX compared to ADA.

IFX and ADA are comparable in clinical outcomes for patients with CD who are naïve or non-naïve to anti-TNF-α antagonists. However, fewer overall adverse events are noted in ADA patients.

Our study provide reassurance to clinicians by synthesizing current literature suggesting that the ADA and IFX have similar effectiveness in “real-world” use. Larger, long-term, and prospective head-to-head comparison studies will be necessary to confirm these results. More research also will be necessary to explore the cost of anti-TNF-α agents.

We would like to thank all authors of the included primary studies.

| 1. | Cushing K, Higgins PDR. Management of Crohn Disease: A Review. JAMA. 2021;325:69-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 48.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Danese S, Vuitton L, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Biologic agents for IBD: practical insights. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12:537-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 23.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Singh S, Garg SK, Pardi DS, Wang Z, Murad MH, Loftus EV Jr. Comparative efficacy of biologic therapy in biologic-naïve patients with Crohn disease: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:1621-1635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kestens C, van Oijen MG, Mulder CL, van Bodegraven AA, Dijkstra G, de Jong D, Ponsioen C, van Tuyl BA, Siersema PD, Fidder HH, Oldenburg B; Dutch Initiative on Crohn and Colitis (ICC). Adalimumab and infliximab are equally effective for Crohn's disease in patients not previously treated with anti-tumor necrosis factor-α agents. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:826-831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Otake H, Matsumoto S, Mashima H. Does long-term efficacy differ between infliximab and adalimumab after 1 year of continuous administration? Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e6635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zorzi F, Zuzzi S, Onali S, Calabrese E, Condino G, Petruzziello C, Ascolani M, Pallone F, Biancone L. Efficacy and safety of infliximab and adalimumab in Crohn's disease: a single centre study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:1397-1407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Benmassaoud A, Al-Taweel T, Sasson MS, Moza D, Strohl M, Kopylov U, Paradis-Surprenant L, Almaimani M, Bitton A, Afif W, Lakatos PL, Bessissow T. Comparative Effectiveness of Infliximab Versus Adalimumab in Patients with Biologic-Naïve Crohn's Disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63:1302-1310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Varma P, Paul E, Huang C, Headon B, Sparrow MP. A retrospective comparison of infliximab vs adalimumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn disease. Intern Med J. 2016;46:798-804. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Narula N, Kainz S, Petritsch W, Haas T, Feichtenschlager T, Novacek G, Eser A, Vogelsang H, Reinisch W, Papay P. The efficacy and safety of either infliximab or adalimumab in 362 patients with anti-TNF-α naïve Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:170-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Macaluso FS, Fries W, Privitera AC, Cappello M, Siringo S, Inserra G, Magnano A, Di Mitri R, Mocciaro F, Belluardo N, Scarpulla G, Magrì G, Trovatello A, Carroccio A, Genova S, Bertolami C, Vassallo R, Romano C, Citrano M, Accomando S, Ventimiglia M, Renna S, Orlando R, Rizzuto G, Porcari S, Ferracane C, Cottone M, Orlando A; Sicilian Network for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases [SN-IBD]. A Propensity Score-matched Comparison of Infliximab and Adalimumab in Tumour Necrosis Factor-α Inhibitor-naïve and Non-naïve Patients With Crohn's Disease: Real-Life Data From the Sicilian Network for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:209-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kaniewska M, Rosołowski M, Rydzewska G. Efficacy, tolerability, and safety of infliximab biosimilar in comparison to originator biologic and adalimumab in patients with Crohn disease. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2019;129:484-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cosnes J, Sokol H, Bourrier A, Nion-Larmurier I, Wisniewski A, Landman C, Marteau P, Beaugerie L, Perez K, Seksik P. Adalimumab or infliximab as monotherapy, or in combination with an immunomodulator, in the treatment of Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:1102-1113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Di Domenicantonio R, Trotta F, Cascini S, Agabiti N, Kohn A, Gasbarrini A, Davoli M, Addis A. Population-based cohort study on comparative effectiveness and safety of biologics in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Epidemiol. 2018;10:203-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bau M, Zacharias P, Ribeiro DA, Boaron L, Steckert Filho A, Kotze PG. Safety profile of anti-TNF therapy in Crohn's disease management: A Brazilian single-center direct retrospective comparison between infliximab and adalimumab. Arq Gastroenterol. 2017;54:328-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tursi A, Elisei W, Picchio M, Penna A, Lecca PG, Forti G, Giorgetti G, Faggiani R, Zampaletta C, Pelecca G, Brandimarte G. Effectiveness and safety of infliximab and adalimumab for ambulatory Crohn's disease patients in primary gastroenterology centres. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;25:485-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Doecke JD, Hartnell F, Bampton P, Bell S, Mahy G, Grover Z, Lewindon P, Jones LV, Sewell K, Krishnaprasad K, Prosser R, Marr D, Fischer J, R Thomas G, Tehan JV, Ding NS, Cooke SE, Moss K, Sechi A, De Cruz P, Grafton R, Connor SJ, Lawrance IC, Gearry RB, Andrews JM, Radford-Smith GL; Australian and New Zealand Inflammatory Bowel Disease Consortium. Infliximab vs. adalimumab in Crohn's disease: results from 327 patients in an Australian and New Zealand observational cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:542-552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ma C, Huang V, Fedorak DK, Kroeker KI, Dieleman LA, Halloran BP, Fedorak RN. Crohn's disease outpatients treated with adalimumab have an earlier secondary loss of response and requirement for dose escalation compared to infliximab: a real life cohort study. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1454-1463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ji CC, Takano S. Clinical efficacy of adalimumab vs infliximab and the factors associated with recurrence or aggravation during treatment of anal fistulas in Crohn's disease. Intest Res. 2017;15:182-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Vande Casteele N, Abreu MT, Flier S, Papamichael K, Rieder F, Silverberg MS, Khanna R, Okada L, Yang L, Jain A, Cheifetz AS. Patients With Low Drug Levels or Antibodies to a Prior Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Are More Likely to Develop Antibodies to a Subsequent Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:465-467.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Sasson AN, Ananthakrishnan AN. High Anti-Infliximab Antibody Titers Do Not Impact Response to Subsequent Adalimumab Treatment in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Matsumoto T, Motoya S, Watanabe K, Hisamatsu T, Nakase H, Yoshimura N, Ishida T, Kato S, Nakagawa T, Esaki M, Nagahori M, Matsui T, Naito Y, Kanai T, Suzuki Y, Nojima M, Watanabe M, Hibi T; DIAMOND study group. Adalimumab Monotherapy and a Combination with Azathioprine for Crohn's Disease: A Prospective, Randomized Trial. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:1259-1266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Inokuchi T, Takahashi S, Hiraoka S, Toyokawa T, Takagi S, Takemoto K, Miyaike J, Fujimoto T, Higashi R, Morito Y, Nawa T, Suzuki S, Nishimura M, Inoue M, Kato J, Okada H. Long-term outcomes of patients with Crohn's disease who received infliximab or adalimumab as the first-line biologics. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;34:1329-1336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Roda G, Jharap B, Neeraj N, Colombel JF. Loss of Response to Anti-TNFs: Definition, Epidemiology, and Management. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2016;7:e135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 326] [Cited by in RCA: 560] [Article Influence: 56.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Fukata M, Japan; Ribeiro IB, Brazil S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Fan JR