Published online Jun 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i16.5253

Peer-review started: December 30, 2021

First decision: March 7, 2022

Revised: March 9, 2022

Accepted: April 22, 2022

Article in press: April 22, 2022

Published online: June 6, 2022

Processing time: 153 Days and 11.1 Hours

The impacts of chemotherapy on patients with malignant gastrointestinal obstructions remain unclear, and multicenter evidence is lacking.

To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of chemotherapy in patients with unresectable malignant gastrointestinal obstructions.

We conducted a multicenter retrospective cohort study that compared the chemotherapy group who received any chemotherapeutics after interventions, including palliative surgery or self-expandable metal stent placement, for unresectable malignant gastrointestinal obstruction vs the best supportive care (BSC) group between 2014 and 2019 in nine hospitals. The primary outcome was overall survival, and the secondary outcomes were patency duration and adverse events, including gastrointestinal perforation and gastrointestinal bleeding.

In total, 470 patients in the chemotherapy group and 652 patients in the BSC group were analyzed. During the follow-up period of 54.1 mo, the median overall survival durations were 19.3 mo in the chemotherapy group and 5.4 mo in the BSC group (log-rank test, P < 0.01). The median patency durations were 9.7 mo [95% confidence interval (CI): 7.7-11.5 mo] in the chemotherapy group and 2.5 mo (95%CI: 2.0-2.9 mo) in the BSC group (log-rank test, P < 0.01). The perforation rate was 1.3% (6/470) in the chemotherapy group and 0.9% (6/652) in the BSC group (P = 0.567). The gastrointestinal bleeding rate was 1.5% (7/470) in the chemotherapy group and 0.5% (3/652) in the BSC group (P = 0.105).

Chemotherapy after interventions for unresectable malignant gastrointestinal obstruction was associated with increased overall survival and patency duration.

Core Tip: The impacts of chemotherapy on patients with malignant gastrointestinal obstructions remain unclear, and multicenter evidence is lacking. Does chemotherapy improve the duration of gastrointestinal patency (and thus overall survival) in such patients? This multicenter observational study revealed that the median patency duration in the chemotherapy group was longer than that in the best supportive care group (9.7 vs 2.5 mo). Similarly, the median overall survival was longer in the chemotherapy than the best supportive care group (19.3 vs 5.4 mo, log-rank test, P < 0.01).

- Citation: Fujisawa G, Niikura R, Kawahara T, Honda T, Hasatani K, Yoshida N, Nishida T, Sumiyoshi T, Kiyotoki S, Ikeya T, Arai M, Hayakawa Y, Kawai T, Fujishiro M. Effectiveness and safety of chemotherapy for patients with malignant gastrointestinal obstruction: A Japanese population-based cohort study. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(16): 5253-5265

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i16/5253.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i16.5253

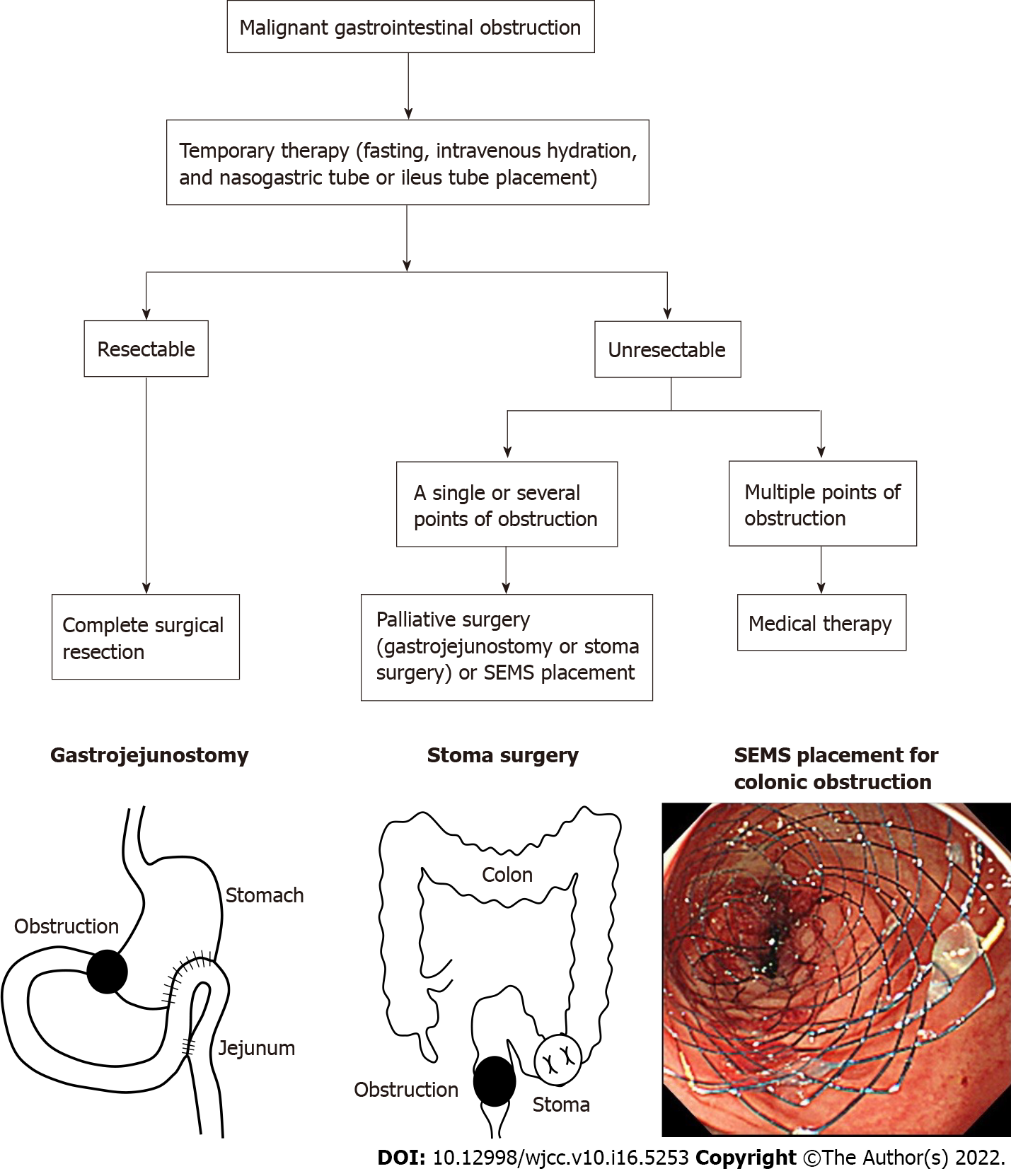

Malignant gastrointestinal obstruction is an important issue in advanced cancer and occurs in approximately 30% of patients with gastrointestinal cancer[1]. Gastrointestinal obstruction causes oral intake impairment, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain and also poses a risk of gastrointestinal perforation. Primary therapy involves fasting, intravenous hydration, and nasogastric tube or ileus tube placement for bowel rest and decompression[2,3]. In secondary therapy, complete surgical resection is performed for resectable malignant gastrointestinal obstruction; palliative surgery, including bypass and stoma surgery or self-expandable metal stent (SEMS) placement, is performed at one or more points of unresectable malignant gastrointestinal obstruction (Figure 1).

Chemotherapy after palliative surgery or SEMS placement is a particularly challenging clinical issue. Although it can improve overall survival[4-6], little is known regarding the difference in overall survival between patients undergoing chemotherapy treatment and those receiving best supportive care (BSC). In addition, the risk of gastrointestinal perforation is a concern for treatment involving chemotherapy combined with SEMS[7,8]. However, previous studies on the safety of chemotherapy in this situation were limited by small sample sizes.

We performed a large multicenter cohort study to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of chemo

We performed a retrospective cohort study using the diagnostic procedure combination (DPC) databases of nine hospitals between January 2014 and March 2019. The combined database comprised the records of all inpatients and outpatients at the University of Tokyo Hospital, Shuto General Hospital, Fukui Prefectural Hospital, Nerima Hikarigaoka Hospital, St. Luke’s International Hospital, Toyonaka Municipal Hospital, Ishikawa Prefectural Central Hospital, and Nagasaki Minato Medical Center and of inpatients at Tonan Hospital. The database included diagnoses, comorbidities, and adverse events using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision and Japanese original disease codes. It also included the cancer stage according to the Union for International Cancer Control classification system[9], Japanese original medication and procedure codes, and Barthel index (BI)[10].

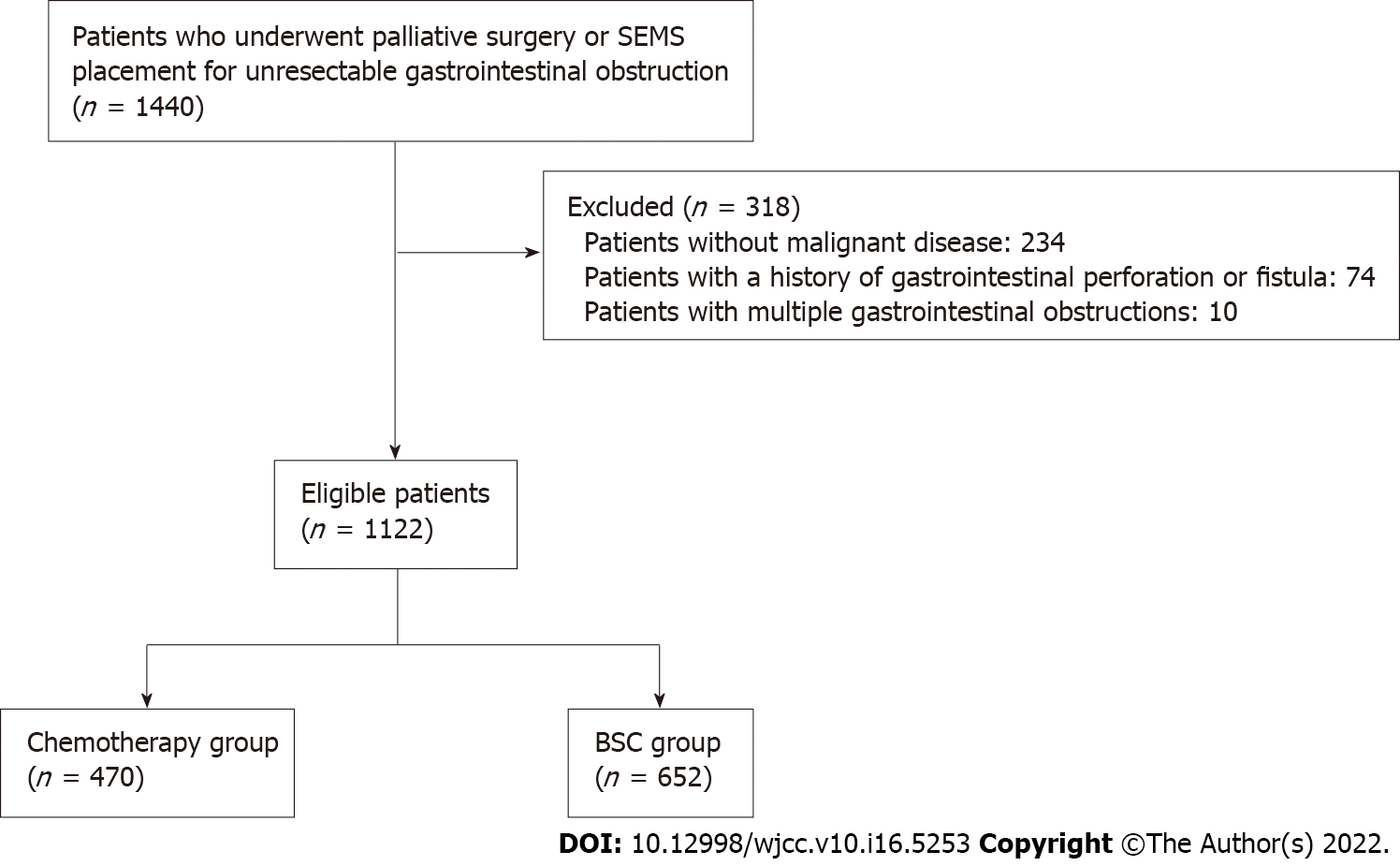

From the database, we identified patients who had undergone palliative surgery or SEMS placement for gastrointestinal obstruction, including esophageal bypass surgery, gastrojejunostomy, duodenojejunostomy, intestinal bypass surgery, stoma surgery, esophageal stenting, gastroduodenal stenting, or colonic stenting, who did not undergo gastrointestinal tract resection thereafter. We excluded patients without malignant disease, those with a history of gastrointestinal perforation or fistula, and patients with multifocal gastrointestinal obstructions. The codes used for patient selection are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

We selected the chemotherapy group (patients who received any chemotherapy drugs after the intervention) with the BSC group (patients who did not receive chemotherapy drugs after the intervention) (Figure 1). The follow-up period was from the date of the intervention to death or the final visit. The end of follow-up was March 2019, and loss to follow-up was defined as the date of the final visit. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Tokyo Hospital (No. 2019161NI).

The primary outcome was overall survival. The secondary outcomes were patency duration and adverse events, including perforation and gastrointestinal bleeding. Patency duration was defined as the time between the first food intake after the intervention and reintervention, stopping food intake, or death. Perforation was defined as surgery for suture, drainage, or intra-abdominal lavage. Gastrointestinal bleeding was defined as any gastrointestinal bleeding requiring endoscopic hemostasis. The procedure codes for outcomes are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

We evaluated the following clinical factors: Age, sex, comorbidities, BI, medication use, cancer type, cancer stage, obstruction site, chemotherapy before the intervention, and intervention type. Age was categorized into < 75 years and ≥ 75 years. Comorbidities were evaluated by the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI)[11] and categorized as < 3 and ≥ 3. BI was categorized as ≥ 60, < 60, and missing. We evaluated the use of aspirin, thienopyridine, warfarin, direct oral anticoagulants (including dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban), other antiplatelet drugs (including dilazep hydrochloride hydrate, dipyridamole, trapidil, cilostazol, limaprost alfadex, ethyl icosapentate, beraprost sodium, sarpogrelate hydrochloride, and ozagrel sodium), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and steroids. The cancer type was categorized into esophageal cancer, gastric cancer, pancreatic cancer, colorectal cancer, and other cancers. The cancer stage was categorized into stage I–III, stage IV or recurrence, and missing. The obstruction site was categorized as esophageal obstruction, gastroduodenal obstruction, or lower gastrointestinal obstruction. The intervention type was categorized as palliative surgery or SEMS placement. The International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision codes of primary cancers and comorbidities are listed in Supplementary Table 3, and the medication codes are shown in Supple

Overall survival and patency durations were estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method and were compared by log-rank test. Data were censored at the date of the final visit. Univariate Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate crude hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) using age, sex, cancer type, cancer stage, CCI, BI, and intervention type.

Categorical data were compared by the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test and continuous data by the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. A P value < 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS software v. 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States).

Fourteen hundred forty patients who had undergone palliative surgery or SEMS placement for unresectable gastrointestinal obstruction were extracted from the DPC database. After excluding patients without malignant disease (n = 234), those with a history of gastrointestinal perforation or fistula (n = 74), and patients with multifocal gastrointestinal obstructions (n = 10), the remaining 1122 patients were analyzed. In total, 470 patients who received chemotherapy drugs after the intervention (chemotherapy group) and 652 patients who did not receive chemotherapy drugs after the intervention (BSC group) were analyzed (Figure 2). The patients’ baseline characteristics are listed in Table 1. The age, CCI, BI, medication, cancer type, and cancer stage distributions were significantly different between the groups. The chemotherapy group had higher rates of < 75 aged patients, CCI ≥ 3, BI ≥ 60, and stage IV or recurrence.

| Variable | Chemotherapy (n = 470), n (%) | BSC (n = 652), n (%) | P value |

| Age | |||

| Young (age < 75 yr) | 375 (79.8) | 335 (51.4) | < 0.001 |

| Elder (age ≥ 75 yr) | 95 (20.2) | 317 (48.6) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 284 (60.4) | 363 (55.7) | 0.112 |

| Female | 186 (39.6) | 289 (44.3) | |

| Charlson co-morbidity index score | |||

| < 3 | 175 (37.2) | 343 (52.6) | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 3 | 295 (62.8) | 309 (47.4) | |

| Barthel index | |||

| ≥ 60 | 422 (89.8) | 436 (66.9) | < 0.001 |

| < 60 | 27 (5.7) | 153 (23.5) | |

| Missing | 21 (4.5) | 63 (9.7) | |

| Medication | |||

| Aspirin | 18 (3.8) | 33 (5.1) | 0.329 |

| Thienopyridine | 7 (1.5) | 24 (3.7) | 0.027 |

| Warfarin | 8 (1.7) | 20 (3.1) | 0.148 |

| DOACs | 34 (7.2) | 29 (4.4) | 0.045 |

| Other antiplatelet drugs | 7 (1.5) | 33 (5.1) | 0.001 |

| NSAIDs | 293 (62.3) | 314 (48.2) | < 0.001 |

| Steroids | 201 (42.8) | 154 (23.6) | < 0.001 |

| Cancer type | |||

| Esophageal cancer | 24 (5.1) | 83 (12.7) | < 0.001 |

| Gastric cancer | 151 (32.1) | 113 (17.3) | |

| Pancreatic cancer | 69 (14.7) | 106 (16.3) | |

| Colorectal cancer | 146 (31.1) | 212 (32.5) | |

| Other cancers | 80 (17.0) | 138 (21.2) | |

| Cancer stage | |||

| Stage I-III | 81 (17.2) | 157 (24.1) | 0.022 |

| Stage IV or recurrence | 297 (63.2) | 379 (58.1) | |

| Missing | 92 (19.6) | 116 (17.8) | |

| Obstruction site | |||

| Esophageal obstruction | 38 (8.1) | 105 (16.1) | < 0.001 |

| Gastroduodenal obstruction | 189 (40.2) | 233 (35.7) | |

| Lower gastrointestinal obstruction | 243 (51.7) | 314 (48.2) | |

| Chemotherapy before the intervention | 274 (58.3) | 413 (63.3) | 0.087 |

| Intervention type | |||

| Palliative surgery | 294 (62.6) | 283 (43.4) | < 0.001 |

| SEMS placement | 176 (37.4) | 369 (56.6) |

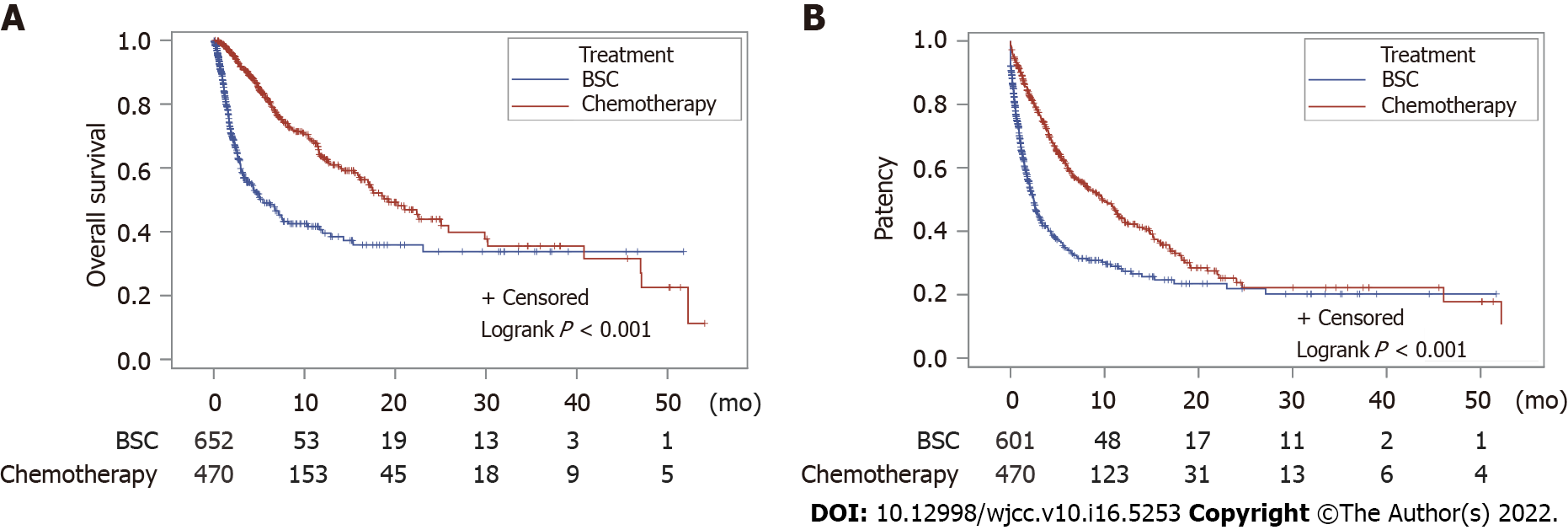

During the follow-up period of 54.1 mo, the median overall survival durations were 19.3 mo (95%CI: 16.2-25.9 mo) in the chemotherapy group and 5.4 mo (95%CI: 3.6-7.6 mo) in the BSC group (log-rank test, P < 0.01; Figure 2). The median patency durations were 9.7 mo (95%CI: 7.7-11.5 mo) in the chemotherapy group and 2.5 mo (95%CI: 2.0-2.9 mo) in the BSC group (log-rank test, P < 0.01; Figure 3).

The factors affecting overall survival are shown in Table 2. Multivariate analysis showed that the factors affecting overall survival were chemotherapy after the intervention (aHR, 0.36), CCI ≥ 3 (aHR, 1.56), BI < 60 (aHR, 2.04), gastric cancer compared with esophageal cancer (aHR, 0.64), colorectal cancer compared with esophageal cancer (aHR, 0.47), stage IV or recurrence compared with stage I–III (aHR, 1.79), chemotherapy before the intervention (aHR, 1.66), and SEMS placement compared with palliative surgery (aHR, 1.63).

| Factor | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| Crude HR (95%CI) | P value | Adjusted HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| BSC | 1 | 1 | ||

| Chemotherapy after the intervention | 0.38 (0.31-0.48) | < 0.001 | 0.36 (0.28-0.46) | < 0.001 |

| Age | ||||

| Young (age < 75 yr) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Elder (age ≥ 75 yr) | 1.39 (1.10-1.75) | 0.005 | 1.17 (0.92-1.49) | 0.208 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1 | 1 | ||

| Female | 1.05 (0.84-1.30) | 0.673 | 1.03 (0.83-1.29) | 0.782 |

| Charlson co-morbidity index | ||||

| < 3 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥ 3 | 1.59 (1.27-2.00) | < 0.001 | 1.56 (1.24-1.97) | < 0.001 |

| Barthel index | ||||

| ≥ 60 | 1 | 1 | ||

| < 60 | 2.16 (1.64-2.84) | < 0.001 | 2.04 (1.53-2.73) | < 0.001 |

| Medication | ||||

| Aspirin non-use | 1 | 1 | ||

| Aspirin use | 1.01 (0.62-1.64) | 0.980 | 0.81 (0.49-1.33) | 0.399 |

| Thienopyridine non-use | 1 | 1 | ||

| Thienopyridine use | 1.32 (0.70-2.47) | 0.391 | 1.07 (0.56-2.03) | 0.843 |

| Warfarin non-use | 1 | 1 | ||

| Warfarin use | 0.93 (0.42-2.09) | 0.863 | 0.90 (0.40-2.02) | 0.791 |

| DOACs non-use | 1 | 1 | ||

| DOACs use | 1.31 (0.87-1.95) | 0.193 | 1.27 (0.85-1.91) | 0.250 |

| Other antiplatelet drugs non-use | 1 | 1 | ||

| Other antiplatelet drugs use | 1.06 (0.60-1.89) | 0.837 | 1.04 (0.58-1.86) | 0.904 |

| NSAIDs non-use | 1 | 1 | ||

| NSAIDs use | 0.99 (0.80-1.23) | 0.948 | 1.05 (0.83-1.33) | 0.674 |

| Steroid non-use | 1 | 1 | ||

| Steroid use | 1.26 (1.02-1.57) | 0.035 | 1.15 (0.92-1.45) | 0.210 |

| Cancer type | ||||

| Esophageal cancer | 1 | 1 | ||

| Gastric cancer | 0.68 (0.47-0.99) | 0.045 | 0.64 (0.43-0.96) | 0.030 |

| Pancreatic cancer | 1.00 (0.67-1.48) | 0.991 | 0.92 (0.61-1.39) | 0.697 |

| Colorectal cancer | 0.40 (0.27-0.59) | < 0.001 | 0.47 (0.30-0.73) | < 0.001 |

| Other cancers | 0.77 (0.53-1.13) | 0.186 | 0.78 (0.51-1.18) | 0.242 |

| Cancer stage | ||||

| Stage I-III | 1 | 1 | ||

| Stage IV or recurrence | 1.96 (1.43-2.70) | < 0.001 | 1.79 (1.28-2.50) | < 0.001 |

| Obstruction site | ||||

| Esophageal obstruction | 1 | 1 | ||

| Gastroduodenal obstruction | 0.84 (0.61-1.15) | 0.274 | 1.03 (0.58-1.82) | 0.918 |

| Lower gastrointestinal obstruction | 0.48 (0.35-0.66) | < 0.001 | 0.78 (0.42-1.44) | 0.426 |

| Non-chemotherapy before the intervention | 1 | 1 | ||

| Chemotherapy before the intervention | 2.08 (1.68-2.57) | < 0.001 | 1.66 (1.31-2.09) | < 0.001 |

| Intervention type | ||||

| Palliative surgery | 1 | 1 | ||

| SEMS placement | 2.03 (1.63-2.51) | < 0.001 | 1.63 (1.27-2.09) | < 0.001 |

The factors affecting patency are shown in Table 3. Multivariate analysis showed that the factors affecting patency duration were chemotherapy after the intervention (aHR, 0.49), CCI ≥ 3 (aHR, 1.41), BI < 60 (aHR, 1.55), colorectal cancer vs esophageal cancer (aHR, 0.67), stage IV or recurrence compared with stage I–III (aHR, 1.65), chemotherapy before the intervention (aHR, 1.64), and SEMS placement compared with palliative surgery (aHR, 2.48).

| Factor | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| Crude HR (95%CI) | P value | Adjusted HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| BSC | 1 | 1 | ||

| Chemotherapy after the intervention | 0.50 (0.42-0.59) | < 0.001 | 0.49 (0.41-0.59) | < 0.001 |

| Age | ||||

| Young (< 75 yr) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Elder (≥ 75 yr) | 1.10 (0.92-1.33) | 0.302 | 0.96 (0.79-1.17) | 0.701 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1 | 1 | ||

| Female | 1.01 (0.85-1.20) | 0.879 | 1.00 (0.84-1.19) | 0.991 |

| Charlson co-morbidity index | ||||

| < 3 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥ 3 | 1.44 (1.21-1.72) | < 0.001 | 1.41 (1.18-1.69) | < 0.001 |

| Barthel index | ||||

| ≥ 60 | 1 | 1 | ||

| < 60 | 1.57 (1.24-1.97) | < 0.001 | 1.55 (1.22-1.97) | < 0.001 |

| Medication | ||||

| Aspirin non-use | 1 | 1 | ||

| Aspirin use | 1.00 (0.67-1.49) | 0.992 | 0.82 (0.55-1.24) | 0.350 |

| Thienopyridine non-use | 1 | 1 | ||

| Thienopyridine use | 0.89 (0.50-1.58) | 0.700 | 0.77 (0.43-1.37) | 0.367 |

| Warfarin non-use | 1 | 1 | ||

| Warfarin use | 0.97 (0.52-1.82) | 0.935 | 0.89 (0.47-1.67) | 0.707 |

| DOACs non-use | 1 | 1 | ||

| DOACs use | 1.22 (0.88-1.70) | 0.224 | 1.28 (0.92-1.79) | 0.137 |

| Other antiplatelet drugs non-use | 1 | 1 | ||

| Other antiplatelet drugs use | 1.05 (0.66-1.66) | 0.833 | 1.05 (0.66-1.66) | 0.851 |

| NSAIDs non-use | 1 | 1 | ||

| NSAIDs use | 0.92 (0.78-1.10) | 0.367 | 1.05 (0.87-1.26) | 0.603 |

| Steroid non-use | 1 | 1 | ||

| Steroid use | 1.19 (1.00-1.42) | 0.046 | 1.05 (0.88-1.26) | 0.603 |

| Cancer type | ||||

| Esophageal cancer | 1 | 1 | ||

| Gastric cancer | 0.86 (0.64-1.16) | 0.321 | 0.98 (0.71-1.34) | 0.888 |

| Pancreatic cancer | 1.11 (0.80-1.52) | 0.531 | 1.18 (0.85-1.64) | 0.324 |

| Colorectal cancer | 0.42 (0.30-0.57) | < 0.001 | 0.67 (0.47-0.95) | 0.024 |

| Other cancers | 0.75 (0.55-1.03) | 0.073 | 0.97 (0.69-1.36) | 0.858 |

| Cancer stage | ||||

| Stage I-III | 1 | 1 | ||

| Stage IV or recurrence | 1.87 (1.46-2.39) | < 0.001 | 1.65 (1.28-2.14) | < 0.001 |

| Obstruction site | ||||

| Esophageal obstruction | 1 | 1 | ||

| Gastroduodenal obstruction | 0.88 (0.68-1.13) | 0.325 | 1.22 (0.80-1.88) | 0.356 |

| Lower gastrointestinal obstruction | 0.51 (0.39-0.66) | < 0.001 | 1.30 (0.81-2.08) | 0.269 |

| Non-chemotherapy before the intervention | 1 | 1 | ||

| Chemotherapy before the intervention | 2.11 (1.78-2.50) | < 0.001 | 1.64 (1.36-1.98) | < 0.001 |

| Intervention type | ||||

| Palliative surgery | 1 | 1 | ||

| SEMS placement | 2.84 (2.38-3.39) | < 0.001 | 2.48 (2.03-3.03) | < 0.001 |

The results of a subgroup analysis of adjusted HRs for overall survival and patency duration were consistent with those of the overall analysis (Table 4).

| Subgroups | Overall survival | Patency duration | ||

| Adjusted HR (95%CI) | P value | Adjusted HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| All patients | 0.36 (0.28-0.46) | < 0.001 | 0.49 (0.41-0.59) | < 0.001 |

| Age | ||||

| Young (< 75 yr) | 0.36 (0.27-0.48) | < 0.001 | 0.48 (0.39-0.60) | < 0.001 |

| Elder (≥ 75 yr) | 0.38 (0.24-0.61) | < 0.001 | 0.52 (0.35-0.76) | < 0.001 |

| Charlson co-morbidity index | ||||

| < 3 | 0.43 (0.27-0.68) | < 0.001 | 0.47 (0.33-0.67) | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 3 | 0.31 (0.23-0.41) | < 0.001 | 0.47 (0.37-0.59) | < 0.001 |

| Barthel index | ||||

| ≥ 60 | 0.38 (0.29-0.50) | < 0.001 | 0.52 (0.42-0.64) | < 0.001 |

| < 60 | 0.24 (0.11-0.54) | < 0.001 | 0.26 (0.13-0.51) | < 0.001 |

| Cancer type | ||||

| Esophageal cancer | 0.45 (0.21-1.00) | 0.049 | 0.80 (0.43-1.49) | 0.479 |

| Gastric cancer | 0.38 (0.24-0.62) | < 0.001 | 0.62 (0.43-0.90) | 0.012 |

| Pancreatic cancer | 0.14 (0.07-0.29) | < 0.001 | 0.28 (0.17-0.45) | < 0.001 |

| Colorectal cancer | 0.45 (0.25-0.78) | 0.005 | 0.45 (0.29-0.70) | < 0.001 |

| Obstruction site | ||||

| Esophageal obstruction | 0.46 (0.23-0.92) | 0.028 | 0.80 (0.47-1.37) | 0.425 |

| Gastroduodenal obstruction | 0.26 (0.18-0.39) | < 0.001 | 0.37 (0.28-0.50) | < 0.001 |

| Lower gastrointestinal obstruction | 0.44 (0.30-0.64) | < 0.001 | 0.51 (0.38-0.69) | < 0.001 |

| Intervention type | ||||

| Palliative surgery | 0.34 (0.24-0.48) | < 0.001 | 0.39 (0.29-0.52) | < 0.001 |

| SEMS placement | 0.37 (0.26-0.52) | < 0.001 | 0.54 (0.42-0.70) | < 0.001 |

The rates of adverse events are listed in Table 5. The perforation rate was 1.3% (6/470) in the chemotherapy group (3 gastric cancers, one colorectal cancer, 1 breast cancer, and 1 unclassifiable cancer) and 0.9% (6/652) in the BSC group (3 colorectal cancers, 2 gastric cancers, and 1 esophageal cancer) (P = 0.567). In 4 of the 6 perforation cases in the chemotherapy group, perforation occurred a mean of 137 d after chemotherapy initiation.

| Chemotherapy (n = 470), n (%) | BSC (n = 652), n (%) | P value | |

| Perforation | 6 (1.3) | 6 (0.9) | 0.567 |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 7 (1.5) | 3 (0.5) | 0.105 |

The gastrointestinal bleeding rate was 1.5% (7/470) in the chemotherapy group (4 gastric cancers, 1 esophageal cancer, 1 pancreatic cancer, and o1colorectal cancer) and 0.5% (3/652) in the BSC group (1 esophageal cancer and 2 pancreatic cancers) (P = 0.105). In 4 of 7 bleeding cases in the chemotherapy group, gastrointestinal bleeding occurred a mean of 294 d after chemotherapy initiation.

Chemotherapy after palliative surgery or SEMS placement for unresectable malignant gastrointestinal obstruction was associated with improved overall survival and patency duration and not associated with increased perforation or gastrointestinal bleeding compared with BSC. In addition, its effectiveness for overall survival and patency duration was consistent among cancer types and obstruction sites.

The chemotherapy group showed longer overall survival and patency durations. We suggest three reasons for these findings. First, chemotherapy drugs may prolong overall survival and patency duration even in patients with malignant gastrointestinal obstruction. We performed a multivariate analysis to reduce the influence of confounders; chemotherapy after the intervention was an independent factor for overall survival and patency duration. Previous studies reported similar results. Nomoto et al[6] reported that chemotherapy after bypass surgery for esophageal cancer improved the prognosis. Cho et al[4] showed that chemotherapy after SEMS placement for gastric cancer was a significant prognostic factor for patency duration. Ahn et al[5] reported that chemotherapy after palliative surgery or SEMS placement for colorectal cancer significantly improved survival. Second, bias in terms of patient characteristics may have influenced the results. The chemotherapy group included younger patients, those of higher BI, and more nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs users. This suggests that the chemotherapy group may have previously been treated for other diseases. In turn, this may have increased palliative surgery performance and improved the patency and survival durations. Third, chemotherapy was not associated with increased perforation, which is a fatal complication. The risk of gastrointestinal perforation after SEMS placement is a matter of great concern, particularly when chemotherapy is combined with SEMS. The 2019 clinical guidelines of the Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum[2] does not recommend SEMS placement for patients with colonic obstruction who are indicated for systemic chemotherapy. However, available data on the safety of chemotherapy after palliative surgery or SEMS placement are limited. In this study, the rate of perforation was < 2% in the chemotherapy and BSC groups; however, the definition of perforation was major perforation that required surgery.

We performed a subgroup analysis to identify the optimal population for chemotherapy because this study included heterogenous patients with various cancers and obstruction sites, which could influence the effectiveness of chemotherapy. The effectiveness of chemotherapy after the intervention for overall survival and patency duration was consistent among the cancer types and obstruction sites. Especially in cases of pancreatic cancer and gastroduodenal obstruction, chemotherapy might be more beneficial. The effectiveness of chemotherapy after the intervention was similar among the cancer types and obstruction sites. Especially in cases of pancreatic cancer and gastroduodenal obstruction, chemotherapy may be more beneficial. These findings will help guide future research on treatment approaches and precision medicine. Currently, overall survival and recurrence risk are predicted based on limited data such as pathological findings. However, recent biological research has suggested potential biomarkers, including circulating tumor DNA and micro-RNA, as well as microbiome profiling, to predict overall survival and recurrence. In the near future, these precision medicine methods are expected to contribute to cancer therapies including molecular targeted anti-cancer drugs, monoclonal antibody therapy, and antibiotic therapies.

To our knowledge, this is the first study of the effectiveness and safety of chemotherapy after palliative surgery or SEMS placement for various types of unresectable malignant gastrointestinal obstruction. In addition, our finding showed that chemotherapy was associated with prolongs gastrointestinal patency. However, this study has several limitations. First, it was a retrospective study. Although we used multivariate Cox proportional hazard models to reduce the effects of confounding factors, some bias may remain because the decision to undergo chemotherapy depends on so many factors including unmeasured confounders. It is difficult to evaluate the effect of chemotherapy more accurately in our setting. Second, our study included patients with different types of cancer, and there were different numbers of patients among the cancer groups. Third, the DPC database lacked information on potential prognostic factors such as radiotherapy history and pathological findings.

In conclusion, chemotherapy after palliative surgery or SEMS placement for unresectable malignant gastrointestinal obstruction was associated with increased overall survival and patency duration independent of the cancer type and obstruction site, and it was not associated with an increased rate of gastrointestinal perforation.

Malignant gastrointestinal obstruction is an important issue in advanced cancer and occurs in approximately 30% of patients with gastrointestinal cancer. Gastrointestinal obstruction causes oral intake impairment, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain and increases the risk of gastrointestinal perforation. Primary therapy involves fasting and decompression, and subsequently complete surgical resection is performed for resectable malignant gastrointestinal obstruction; palliative surgery includes bypass and stoma surgery or self-expandable metal stent (SEMS) placement.

The impacts of chemotherapy on patients with malignant gastrointestinal obstructions remain unclear, and multicenter evidence is lacking.

We performed a large multicenter cohort study to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of chemotherapy after palliative surgery or SEMS placement compared with best supportive care (BSC) in patients with unresectable malignant gastrointestinal obstructions. In addition, we aimed to identify the optimal population for chemotherapy after palliative surgery or SEMS placement.

We conducted a multicenter retrospective cohort study that compared the chemotherapy group who received any chemotherapeutics after interventions, including palliative surgery or self-expandable metal stent placement, for unresectable malignant gastrointestinal obstruction vs BSC group between 2014 and 2019 in nine hospitals. The primary outcome was overall survival, and the secondary outcomes were patency duration and adverse events, including gastrointestinal perforation and gastrointestinal bleeding.

In total, 470 patients in the chemotherapy group and 652 patients in the BSC group were analyzed. During the follow-up period of 54.1 mo, the median overall survival durations were 19.3 mo in the chemotherapy group and 5.4 mo in the BSC group (log-rank test, P < 0.01). The median patency durations were 9.7 mo [95% confidence interval (CI): 7.7-11.5 mo] in the chemotherapy group and 2.5 mo (95%CI: 2.0-2.9 mo) in the BSC group (log-rank test, P < 0.01). The perforation rate was 1.3% (6/470) in the chemotherapy group and 0.9% (6/652) in the BSC group (P = 0.567). The gastrointestinal bleeding rate was 1.5% (7/470) in the chemotherapy group and 0.5% (3/652) in the BSC group (P = 0.105).

Chemotherapy after interventions for unresectable malignant gastrointestinal obstruction was associated with increased overall survival and patency duration.

Our results showed that chemotherapy may be more beneficial in cases of pancreatic cancer and gastroduodenal obstruction. These findings will help guide future research on treatment approaches and precision medicine. In the near future, these precision medicine methods are expected to contribute to cancer therapies including molecular targeted anti-cancer drugs, monoclonal antibody therapy, and antibiotic therapies.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Bogach J, Canada; Serban ED, Romania; Tsagkaris C, Switzerland S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Yan JP

| 1. | Cousins SE, Tempest E, Feuer DJ. Surgery for the resolution of symptoms in malignant bowel obstruction in advanced gynaecological and gastrointestinal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;CD002764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hashiguchi Y, Muro K, Saito Y, Ito Y, Ajioka Y, Hamaguchi T, Hasegawa K, Hotta K, Ishida H, Ishiguro M, Ishihara S, Kanemitsu Y, Kinugasa Y, Murofushi K, Nakajima TE, Oka S, Tanaka T, Taniguchi H, Tsuji A, Uehara K, Ueno H, Yamanaka T, Yamazaki K, Yoshida M, Yoshino T, Itabashi M, Sakamaki K, Sano K, Shimada Y, Tanaka S, Uetake H, Yamaguchi S, Yamaguchi N, Kobayashi H, Matsuda K, Kotake K, Sugihara K; Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum. Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (JSCCR) guidelines 2019 for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2020;25:1-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1024] [Cited by in RCA: 1422] [Article Influence: 237.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 3. | van Hooft JE, Veld JV, Arnold D, Beets-Tan RGH, Everett S, Götz M, van Halsema EE, Hill J, Manes G, Meisner S, Rodrigues-Pinto E, Sabbagh C, Vandervoort J, Tanis PJ, Vanbiervliet G, Arezzo A. Self-expandable metal stents for obstructing colonic and extracolonic cancer: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline - Update 2020. Endoscopy. 2020;52:389-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 221] [Article Influence: 36.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cho YK, Kim SW, Hur WH, Nam KW, Chang JH, Park JM, Lee IS, Choi MG, Chung IS. Clinical outcomes of self-expandable metal stent and prognostic factors for stent patency in gastric outlet obstruction caused by gastric cancer. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:668-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ahn HJ, Kim SW, Lee SW, Lim CH, Kim JS, Cho YK, Park JM, Lee IS, Choi MG. Long-term outcomes of palliation for unresectable colorectal cancer obstruction in patients with good performance status: endoscopic stent vs surgery. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:4765-4775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nomoto D, Baba Y, Akiyama T, Okadome K, Uchihara T, Harada K, Eto K, Hiyoshi Y, Nagai Y, Ishimoto T, Iwatsuki M, Iwagami S, Miyamoto Y, Yoshida N, Watanabe M, Baba H. Outcomes of esophageal bypass surgery and self-expanding metallic stent insertion in esophageal cancer: reevaluation of bypass surgery as an alternative treatment. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2020;405:1111-1118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Datye A, Hersh J. Colonic perforation after stent placement for malignant colorectal obstruction--causes and contributing factors. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2011;20:133-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Imbulgoda A, MacLean A, Heine J, Drolet S, Vickers MM. Colonic perforation with intraluminal stents and bevacizumab in advanced colorectal cancer: retrospective case series and literature review. Can J Surg. 2015;58:167-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Brierley JD, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C. TNM classification of malignant tumours. 8th ed. Wiley-Blackwell, 2017. |

| 10. | Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional Evaluation: The Barthel Index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61-65. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32099] [Cited by in RCA: 39488] [Article Influence: 1012.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |