Published online May 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i15.5025

Peer-review started: December 7, 2021

First decision: January 25, 2022

Revised: February 12, 2022

Accepted: March 26, 2022

Article in press: March 26, 2022

Published online: May 26, 2022

Processing time: 168 Days and 0.7 Hours

Neurocutaneous melanosis (NCM) is a rare congenital, nonhereditary neurocutaneous syndrome that mainly occurs in children; adult NCM is very rare. Due to its rarity, the clinical features and treatment strategies for NCM remain unclear. The purpose of this study was to explore the clinical features, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of NCM in adults. Most intracranial meningeal melanomas are solid masses, and cystic-solid malignant melanomas are very rare. Due to the lack of data, the cause of cystic changes and the effect on prognosis are unknown.

A 41-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital with intermittent headache for 1 mo. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a 4.7 cm × 3.6 cm cystic-solid mass in the left temporal lobe with peritumoral edema. The entire mass was removed, and postoperative pathology indicated malignant melanoma.

MRI is the first-choice imaging approach for diagnosing central nervous system diseases in NCM patients, although cerebrospinal fluid may also be used. At present, there is no optimal treatment plan; gross total resection combined with BRAF inhibitors and MEK inhibitors might be the most beneficial treatment.

Core Tip: Neurocutaneous melanosis (NCM) is a rare congenital, nonhereditary neurocutaneous syndrome that mainly occurs in children, while adult NCM is very rare. Due to its rarity, clinical features and treatment strategies for NCM remain unclear. Herein, we report a case and review such reports and explore the clinical features, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of NCM in adults.

- Citation: Liu BC, Wang YB, Liu Z, Jiao Y, Zhang XF. Neurocutaneous melanosis with an intracranial cystic-solid meningeal melanoma in an adult: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(15): 5025-5035

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i15/5025.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i15.5025

Neurocutaneous melanosis (NCM) is a rare congenital, nonhereditary neurocutaneous syndrome that mainly occurs in children; adult NCM is very rare. Specifically, NCM is a rare combined abnormality of the skin and central nervous system (CNS)[1], mainly presenting as congenital melanocytic nevi with benign or malignant melanoma of the central nervous system[2]. NCM is a neuroectodermal dysplasia believed to arise from an embryological defect in the migration of melanoblasts from the neural crest to the leptomeninges and skin[3]; it was first described by Rokitanki in 1861[4]. Patients with NCM usually have neurological symptoms at an early age. Most patients have a poor prognosis once symptoms occur, regardless of whether the CNS tumors are benign or malignant; in most cases, the disease is fatal within 3 years of onset[5]. Primary malignant melanoma in the central nervous system is usually a single solid mass, and melanoma with large cystic changes is extremely rare. Here, we describe a rare adult NCM complicated with intracranial cystic-solid malignant melanoma and review the relevant literature to discuss the clinical features, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis.

The patient was admitted to our department with intermittent headache for 1 mo.

A 41-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital with intermittent headache for 1 mo. The headache could not be relieved by rest. There were no obvious symptoms of nausea, vomiting and epilepsy.

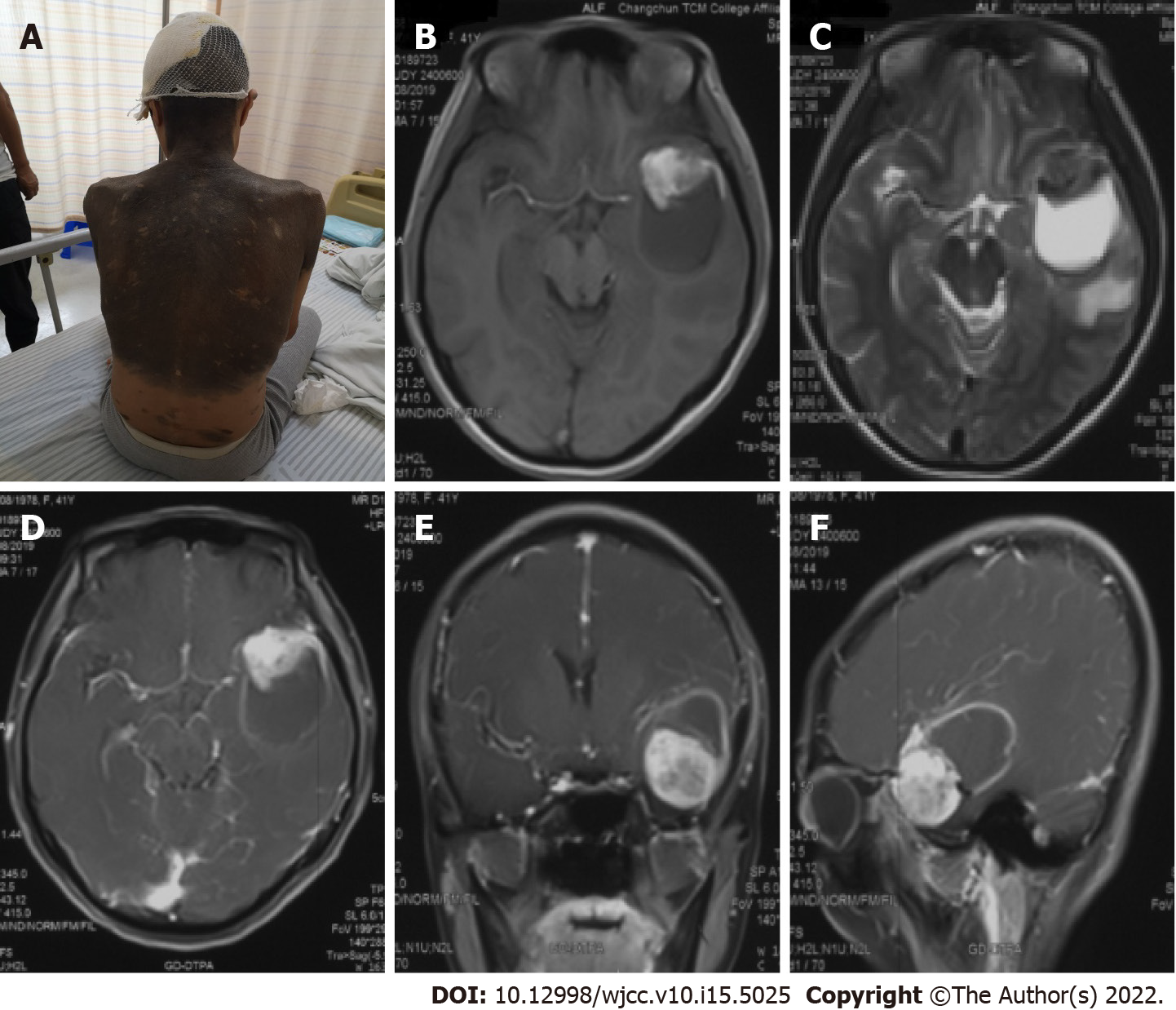

The patient was born with diffuse melanosis of the skin, mainly covering the back of the trunk, shoulders and neck, with multiple satellite nevi on the limbs and a few hairs on the surface of the nevi in the first few years after birth (Figure 1A). The lesion was considered to be a birthmark and had not been treated. No malignant clinical signs, such as enlargement, ulcers, bleeding or itching, were observed in the pigmented area as the patient aged.

There was no past history of skin or CNS disease or malignant tumor. The patient had no history of surgery, and her parents and children had no history of congenital nevi or melanoma.

The patient has diffuse melanosis of the skin, mainly covering the back of the trunk, shoulders and neck, with multiple satellite nevi on the limbs and a few hairs on the surface of the nevi. Examination of her nervous system revealed no obvious abnormalities.

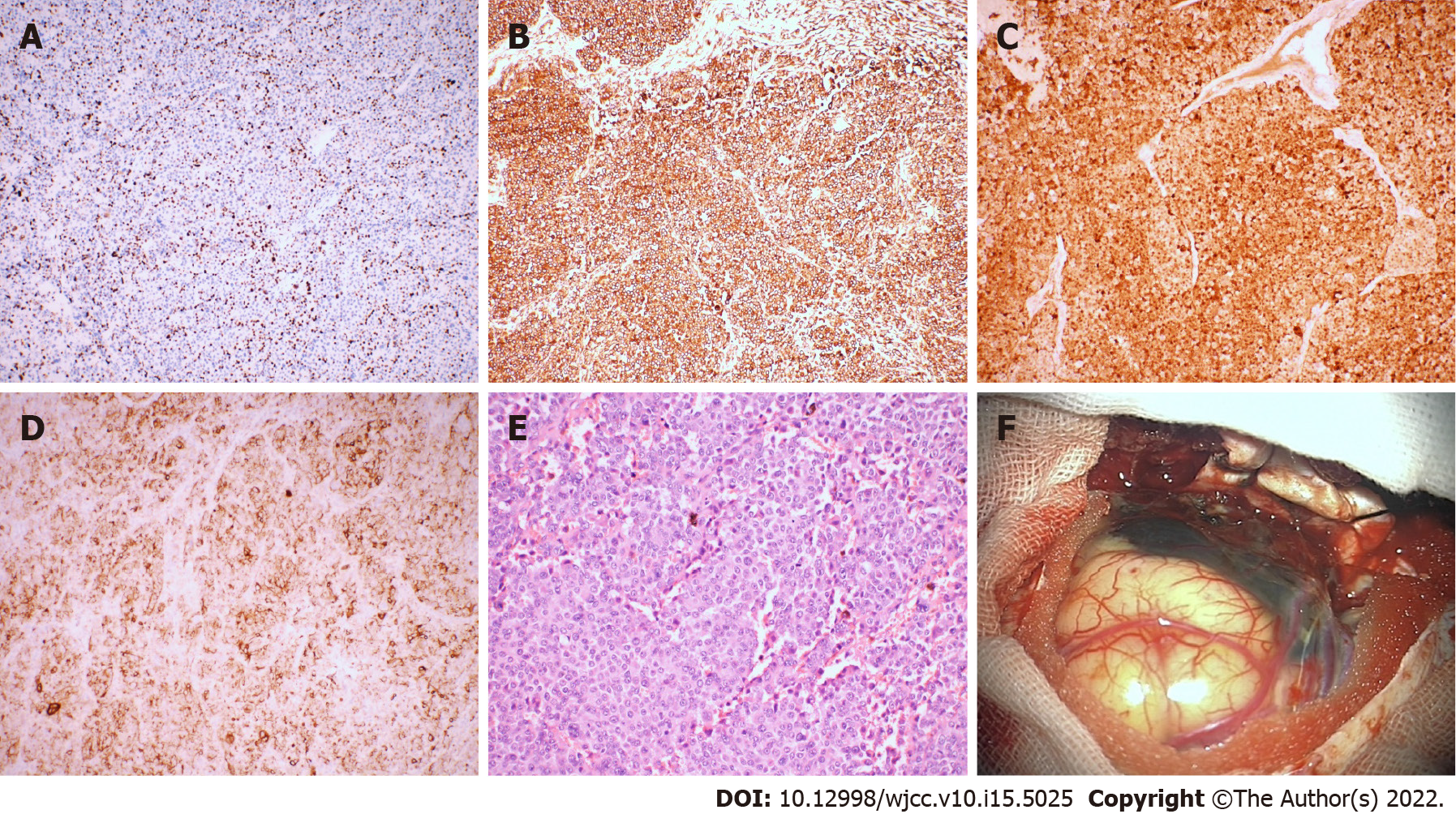

Laboratory examinations such as routine blood tests, routine urine tests and blood biochemistry were normal. The pathological results showed malignant melanoma. Immunohistochemistry results were as follows: Ki-67 (+30%), S-100 (+), HMB45 (+), Vimentin (+); all other markers were negative (Figure 2).

MRI examination of the head revealed a mass with intramural cysts located on the left temporal lobe. The solid part of the tumor was hyperintense on T1-weighted images and hypointense on T2-weighted images, and the cystic components showed the opposite. The lesion had a clear boundary of approximately 4.7 cm x 3.6 cm and was surrounded by peritumoral edema (Figure 1B and C). After the injection of a contrast agent (Gd-DTPA), obvious heterogeneous enhancement was observed in the solid part, while the cystic part showed abnormal ring-shaped enhancement (Figure 1D-F).

We ultimately diagnosed this patient with NCM with meningeal melanoma.

The patient underwent surgery to remove the intracranial mass after admission. During the operation, the tumor appeared blackish brown (the peripheral leptomeninges were also stained black), with light-yellow sac fluid inside, and the blood supply to the tumor was extremely rich. First, the cystic fluid was drawn out, and the lesion was then gradually separated along its periphery until it was completely removed. The pathological results showed malignant melanoma. Immunohistochemistry results were as follows: Ki-67 (+30%), S-100 (+), HMB45 (+), Vimentin (+); all other markers were negative (Figure 2).

The patient was in good condition after the operation; she refused further radiotherapy and chemotherapy and was discharged on the tenth day after the operation. Five months after the operation, the patient went to a local hospital due to unconsciousness after severe headache and died of ineffective treatment. Her death was considered to be due to obstructive hydrocephalus from tumor progression.

We report an adult female patient with a congenital melanocytic nevus (CMN) on her neck, shoulder and back. A space-occupying lesion in the left temporal lobe was found during a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of her head. The tumor was resected en bloc under microscopy, and subsequent histopathology and immunohistochemistry analyses revealed malignant melanoma. Adult NCM and cystic-solid malignant melanomas are very rare. Our present case report may provide an additional reference that can serve as a potential guide for clinicians and radiologists.

In PubMed, we searched for adult NCM cases published between 1990 and 2020. “Neurocutaneous melanosis” was used as the key word and “Adult: 19 + years” as the qualification, and reports without detailed clinical data were excluded. In addition, references cited in selected articles were manually searched and reviewed to identify other potentially eligible studies. Patient data were extracted, and the clinical data were described and analyzed.

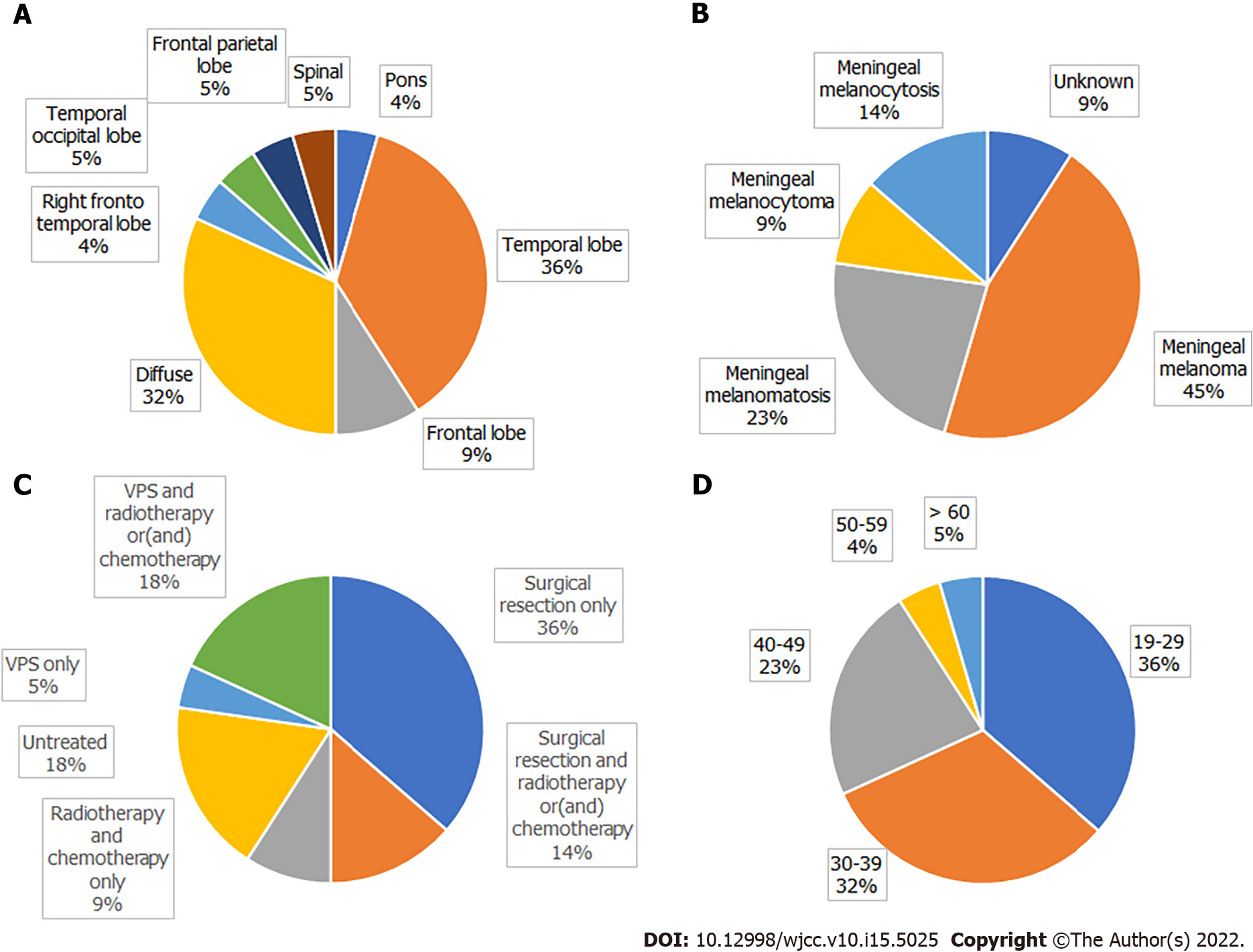

A search of the literature revealed 22 adult NCM cases, including our patient (Table 1); there were 13 males and 9 females, with a male to female ratio of 1.444:1. The mean patient age was 34.13 ± 11.41 years (range: 19-67 years). Congenital melanocytic nevus was most commonly located in the trunk (71.4%), followed by multiple congenital nevi (18.1%). Intracranial hypertension (45%) and epileptic seizures (40%) were the most common first clinical symptoms; others included disturbances of consciousness, movement disorders, and paresthesia. Imaging showed that the lesions were mainly located in the temporal lobe, frontal lobe, and pons. Cystic changes in intracranial melanoma tumors occurred in two patients.

| Ref. | Age (yr)/sex | CMN location | Neurological symptoms | Neurological tumor location | Hydrocephalus | Surgery | Pathology | Chemotherapy/radiotherapy | Follow-up |

| Frisoni et al[28] | 20/M | Back, neck, trunk | Weakness of right lower limb | Left pons | No | None | Unknown | None | Unknown |

| Vadoud-Seyedi et al[29] | 50/F | Back, neck, trunk, limbs | Depression, intracranial hypertension for 4 mo | Right temporal lobe | Yes | STR | Meningeal melanoma | None | 3 wk, death |

| Arunkumar et al[30] | 24/M | Face | Epilepsy for 5 yr | Left frontal lobe, right sphenoid | Yes | STR | Meningeal melanoma | None | 48 h, death |

| Peretti-Viton et al[31] | 19/M | Back, hip | Intracranial hypertension for 4 mo | Left fronto- parietal temporal lobe, diffuse | Yes | None | Meningeal melanocytosis | None | 2 mo, death |

| Shinno et al[10] | 35/M | Sporadic | Intracranial hypertension for 2 mo | Right fronto- temporal lobe, diffuse | No | VPS | Meningeal melanomatosis | Chemotherapy | 30 mo, death |

| de Andrade et al[32] | 21/F | Lower back | Epilepsy started at the age of 7 | Bilateral temporal lobe, pons | No | None | Unknown | None | > 10 yr |

| Tartler et al[8] | 36/M | Lower back, hip | Epilepsy for 1 yr | Left temporal lobe | No | STR, VPS | Meningeal melanoma | Radiotherapy, chemotherapy | Unknown |

| Kang et al[15] | 29/M | Sporadic | Intracranial hypertension for 3 yr, Dandy-Walker syndrome | Bilateral temporal lobe | No | STR | Meningeal melanocytoma | None | Unknown |

| Kiecker et al[11] | 42/M | Head | Right limb weakness, hemianopia, aphasia for 3 wk | Left temporal occipital lobe | No | GTR | Meningeal melanoma | Chemotherapy | 8 mo, relapse |

| Chute et al[33] | 43/M | Head, trunk, limbs | Epilepsy for 5 yr | Left temporal lobe | No | None | Meningeal melanoma | None | 5 yr, death |

| Zhang et al[34] | 25/M | Abdomen, chest, back | Intracranial hypertension for 4 mo | Diffuse, sulcus | Yes | VPS | Meningeal melanocytosis | None | 4 mo, death |

| Walbert et al[6] | 30/F | Sporadic | Epilepsy for 5 yr, Dandy-Walker syndrome | Diffuse | Yes | VPS, GTR | Meningeal melanoma | Radiotherapy, chemotherapy | > 12 mo |

| Ge et al[35] | 37/M | Left arm | Intracranial hypertension for 1 yr | Right frontal parietal lobe | No | STR | Meningeal melanoma | None | 8 d, death |

| Kurokawa et al[36] | 40/F | Trunk | Left leg feels abnormal and weak for 2 yr | T10 cord | No | GTR | Meningeal melanocytoma | None | > 4 yr |

| Oliveira et al[37] | 29/F | Trunk | Epilepsy for 4 mo | Diffuse | No | STR | Meningeal melanomatosis | None | 21 d, death |

| Matsumura et al[7] | 44/M | Trunk, lower limbs | Epilepsy, memory loss | Brain and spine, diffuse | Yes | None | Meningeal melanomatosis | Chemotherapy | 6 mo, death |

| Bhatia et al[5] | 35/M | Trunk, back | Intracranial hypertension for 6 mo | Brain and spine, diffuse | Yes | VPS | Meningeal melanomatosis | Chemotherapy | Unknown |

| Kolin et al[25] | 67/M | Trunk, back | Epilepsy for 6 mo | Meninges, diffuse | Yes | None | Meningeal melanomatosis | Radiotherapy | Unknown |

| Ma et al[16] | 34/F | Trunk, abdomen, head, lower limbs | Intracranial hypertension for 1 wk | Left temporal lobe | No | GTR | Meningeal melanoma | None | 22 mo, death |

| Alessandro et al[9] | 20/F | Sporadic | Epilepsy for 18 mo | Right temporal lobe, diffuse | Yes | VPS | Meningeal melanocytosis | Chemotherapy | 1 mo, death |

| Present report | 41/F | Trunk, back, neck | Intracranial hypertension for 1 mo | Left temporal lobe | No | GTR | Meningeal melanoma | None | 5 mo, death |

| Araújo et al[38] | 30/F | Back, left thigh | Impaired vision, intracranial hypertension for 1 wk | Frontal lobe, cervical vertebrae | No | STR | Meningeal melanoma | Radiotherapy | 7 mo, death |

Subtotal resection of tumors occurred in 6 cases, gross total resection in 5 cases, ventriculoperitoneal shunt in 4 cases, gross total tumor resection plus ventriculoperitoneal shunt in 1 case, and subtotal tumor resection plus ventriculoperitoneal shunt in 1 case. Three patients received postoperative chemotherapy, 2 received postoperative radiotherapy plus chemotherapy, and 2 received chemotherapy without surgery; 4 did not receive treatment. Among those receiving chemotherapy, 5 patients were treated with temozolomide[5-9], 1 patient received combined immunochemotherapy[10], and 1 patient received adjuvant chemotherapy with fotemustine[11]. According to the pathological results, 9 cases of meningeal melanoma, 5 cases of meningeal melanomatosis, 2 cases of meningeal melanocytoma, 3 cases of meningeal melanocytosis, and 3 cases of unknown pathology were diagnosed (Figure 3).

The survival time of 3 patients was not mentioned. There was one special case of a patient who had seizures at the age of 7 and was still alive at the age of 21. The survival period of patients after the appearance of symptoms was 4.75 mo to more than 6 years, and 14 patients (82%) died within 3 years.

According to previous reports, patients with NCM generally develop neurological symptoms at an early age, and most of them die within 3 years after the onset of symptoms. Adult NCM is very rare[5]. The vast majority of patients with NCM are sporadic cases, with few familial cases being reported. Approximately 2/3 of patients with NCM have a giant CMN, and the remaining 1/3 have multiple small lesions[12]. Patients with a giant CMN located on the posterior axis of the trunk and multiple satellite nevi are at higher risk for NCM[13]. The current diagnostic criteria for NCM were revised by Kadonaga et al[14] in 1991 as follows: (1) Large or multiple congenital nevi are observed in association with meningeal melanosis or melanoma. Large refers to a lesion size equal to or greater than 20 cm in diameter in an adult; in neonates and infants, large is defined as a size of 9 cm in the head or 6 cm in the body. Multiple signifies three or more lesions; (2) There is no evidence of cutaneous melanoma, except in patients in whom the examined areas of the meningeal lesions were histologically benign; and (3) There is no evidence of meningeal melanoma, except in patients in whom the cutaneous lesions were histologically benign. According to the above criteria, our patient was diagnosed with NCM. As NCM is very rare, there is no specific incidence. Men seem to be more susceptible to the disease than women, or it is possible that male patients have a greater chance of surviving to adulthood than female patients.

Most intracranial meningeal melanomas are solid masses, and some tumors may have small necrotic cysts inside; cystic-solid malignant melanoma is very rare. In the literature, there were 2 patients with similar lesions. Kang et al[15] reported a patient with NCM who had a cystic-solid meningeal melanocytoma in the left temporal lobe, a dermoid cyst in the right temporal lobe, and Dandy-Walker syndrome. Ma et al[16] reported a patient with NCM who had cystic-solid malignant melanoma in the left temporal lobe and survived for 22 mo after partial resection of the tumor. Combined with our patient, melanoma with large cystic degeneration occurred only in adult patients, and whether tumors were benign or malignant did not seem to have an absolute relationship with cystic degeneration. Due to limited data, it is impossible to clarify the impact of cystic changes in NCM intracranial tumors on the prognosis of patients.

In general, when a cystic mass develops in the central nervous system, the cystic component is caused by tumor necrosis or degeneration. The tumor cyst of our patient was mainly filled with a light-yellow liquid. In the literature, we found that the cysts of some tumors may constitute a nutrient reservoir for brain tumors to ensure that tumor metabolism and tumor cell synthesis can be carried out. Through a component analysis, serum was reported as one of the possible sources of nutrients in most cystic fluids, which may be due to the destruction of the blood–brain barrier by the tumor[17].

Clinical presentations of NCM are nonspecific and vary depending on the tumor site, size and invasion site; these mainly include epilepsy, intracranial hypertension, dyskinesia, and hydrocephalus[9]. Hydrocephalus has been reported in approximately two-thirds of cases and occurs as a result of the obstruction of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow due to melanotic infiltration of arachnoid villi and leptomeninges[12]. Based on our data, the incidence of hydrocephalus in adults was 42.8%. According to this set of data, the peak of neurological symptoms in adult patients is in the third 10 years of life. In addition, the association between Dandy-Walker syndrome and NCM is rare and complex. It has been reported that approximately 8%-10% of cases of Dandy-Walker syndrome are related to NCM[18]. There are currently two theories describing the connection between NCM and Dandy-Walker syndrome. It is thought that melanotic infiltration interferes with the capacity of primitive meningeal cells to induce the normal migration of neurons, deposition of extracellular matrix, and development of normal CSF pathways, leading to posterior fossa cyst formation and vermian dysgenesis. Alternatively, Omar et al[19] suggested that melanosis interferes with the ectodermal-mesodermal interaction, causing an abnormal formation of the fourth ventricle and cerebellum.

Some literature reports have shown that when intracranial lesions of NCM manifest as solid melanoma foci, they are usually asymptomatic[20]. When solid lesions involve the amygdala, pons, and cerebellum, most have a stable or benign course until they develop into malignant melanoma[21]. This may be one reason why NCM does not develop in some patients until adulthood.

At present, MRI is the first-choice imaging approach for diagnosing central nervous system diseases in NCM patients, although it cannot distinguish benign and malignant intracranial tumors. In fact, as melanin pigment is inherently paramagnetic, typical NCM lesions usually exhibit high intensity on T1-weighted images and low intensity to isointensity on T2-weighted images[22]. Due to differences in the melanin content, intracranial melanomas are divided into the melanin type, nonmelanin type, mixed type (melanin type plus nonmelanin type) and blood type according to MRI characteristics[23]. Because NCM does not have a unique clinical manifestation, patients with a giant CMN without neurological symptoms should be examined regularly to rule out the disease. It has been reported that the most common melanin deposits occur in the temporal lobe (especially the amygdala), cerebellum and pons[24]. However, lesions were found in the frontal lobe of some patients, as revealed by our analysis.

There are reports in the literature indicating that CSF can also be used to diagnose NCM. Kolin et al[25] reported on a patient they diagnosed with CSF, which they claimed was the first case report of a diagnosis of primary leptomeningeal melanomatosis (PLM) with an NRAS mutation using a CSF sample for both confirmatory immunocytochemistry and molecular testing. However, in regard to the diagnosis of NCM, we believe that imaging examinations have the advantages of convenience and noninvasiveness. As a result, diagnostic imaging is still the first choice, and CSF examination can be used to further determine whether the lesion is benign or malignant.

Due to the rarity of NCM, a standard treatment approach for this disease has not yet been established. The current treatment options are mainly microsurgery, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, gene therapy, ventricular-peritoneal shunt and comprehensive treatment. However, melanoma in some patients is diffuse and cannot be removed surgically, and it seems that the effects of radiotherapy and chemotherapy cannot effectively extend the life of patients. In the current study, mutations in codon 61 of the NRAS gene were found in most cases. However, there are currently no established targeted therapies for patients with NRAS-mutated melanomas; BRAF inhibitors and MEK inhibitors may be used for treatment, but their effects and safety remain to be determined[26].

Neurocutaneous melanosis usually has a very poor prognosis. The 2016 classification by the World Health Organization categorizes central nervous system melanocyte lesions into meningeal melanocytosis, meningeal melanomatosis, meningeal melanocytoma and meningeal melanoma, where meningeal melanocytosis is considered benign and meningeal melanocytoma is considered relatively benign. The prognosis of meningeal melanoma is very poor. Moreover, the prognosis of patients with NCM is poor, even if the intracranial lesion is diagnosed as benign melanocytosis[16]. According to the literature, most patients die of benign melanocyte overgrowth or malignant transformation within 3 years after symptom onset[27]. In the literature, 15 patients died during follow-up (71%), the survival status of 3 patients was unknown, and 3 patients survived for a long time.

We have tried to analyze the survival data. We excluded the patients without follow-up and the patients died within 3 d after the surgery, 16 patients were included in the survival analysis. Then we divided the patients into different groups (Table 2) and use Kaplan-Meier graph to estimate the overall survival in different groups. The differences between the curves were analyzed by log-rank test, statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05. Unfortunately, we have not found any independent prognostic factors associated with overall survival (Table 3).

| Age (yr) | Sex | Multifocla or diffuse | Hydrocephalus | Tumor resection | Chemotherapy | Radiotherapy | follow up (d) | Vital status |

| 37 | M | No | No | Yes | No | No | 8 | Dead |

| 50 | F | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | 21 | Dead |

| 29 | F | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | 21 | Dead |

| 20 | F | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | 30 | Dead |

| 19 | M | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | 60 | Dead |

| 25 | M | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | 120 | Dead |

| 41 | F | No | No | Yes | No | No | 150 | Dead |

| 44 | M | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | 182 | Dead |

| 30 | F | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | 210 | Dead |

| 42 | M | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | 240 | Alive |

| 30 | F | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 365 | Alive |

| 34 | F | No | No | Yes | No | No | 660 | Dead |

| 35 | M | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | 900 | Dead |

| 40 | F | No | No | Yes | No | No | 1460 | Alive |

| 21 | F | Yes | No | No | No | No | 1825 | Alive |

| 43 | M | No | No | No | No | No | 1825 | Dead |

| Variables | P value |

| Sex | 0.669 |

| Multifocal or diffuse | 0.752 |

| Hydrocephalus | 0.086 |

| Tumor resection | 0.788 |

| Chemotherapy | 0.636 |

| Radiotherapy | 0.614 |

In summary, we report an adult NCM patient and summarize 21 known cases. NCM is relatively rare, especially in adult patients. Among adult patients, the proportion of male patients is higher, and most patients are found to have CMN in the trunk of the body. Therefore, patients with CMN should remain vigilant and undergo regular imaging examinations. At present, MRI is the first-choice imaging approach for diagnosing central nervous system diseases in NCM patients. Most patients develop symptoms when they are young. Although some patients may not have central nervous system symptoms until adulthood, once symptoms appear, the prognosis is poor, regardless of whether the intracranial lesions are benign or malignant. Currently, effective treatments are still lacking. Thus, more case reports describing NCM, as well as long-term follow-up studies, are warranted to fully understand NCM in the adult population. To address these limitations, our present case report provides an additional reference among the few available that can serve as a potential guide for clinicians and radiologists.

| 1. | Gönül M, Soylu S, Gül U, Aslan E, Unal T, Ergül G. Giant congenital melanocytic naevus associated with Dandy-Walker malformation, lipomatosis and hemihypertrophy of the leg. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e106-e109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Agero AL, Benvenuto-Andrade C, Dusza SW, Halpern AC, Marghoob AA. Asymptomatic neurocutaneous melanocytosis in patients with large congenital melanocytic nevi: a study of cases from an Internet-based registry. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:959-965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Scattolin MA, Lin J, Peruchi MM, Rocha AJ, Masruha MR, Vilanova LC. Neurocutaneous melanosis: follow-up and literature review. J Neuroradiol. 2011;38:313-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Taboada-Suárez A, Brea-García B, Suárez-Peñaranda JM, Couto-González I. Neurocutaneous melanosis in association with proliferative skin nodules. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:681-684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bhatia R, Kataria V, Vibha D, Kakkar A, Prasad K, Mathur S, Garg A, Bakhshi S. Mystery Case: Neurocutaneous melanosis with diffuse leptomeningeal malignant melanoma in an adult. Neurology. 2016;86:e75-e79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Walbert T, Sloan AE, Cohen ML, Koubeissi MZ. Symptomatic neurocutaneous melanosis and Dandy-Walker malformation in an adult. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2886-2887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Matsumura M, Okudela K, Tateishi Y, Umeda S, Mitsui H, Suzuki T, Nakayama T, Inayama Y, Ohashi K. Leptomeningeal melanomatosis associated with neurocutaneous melanosis: an autopsy case report. Pathol Int. 2015;65:100-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tartler U, Mang R, Schulte KW, Hengge U, Megahed M, Reifenberger J. [Neurocutaneous melanosis and malignant melanoma]. Hautarzt. 2004;55:971-974. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Alessandro L, Blaquier JB, Bártoli J, Diez B. Diagnostic and therapeutic approach for neurocutaneous melanosis in a young adult. Neurologia (Engl Ed). 2019;34:336-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Shinno K, Nagahiro S, Uno M, Kannuki S, Nakaiso M, Sano N, Horiguchi H. Neurocutaneous melanosis associated with malignant leptomeningeal melanoma in an adult: clinical significance of 5-S-cysteinyldopa in the cerebrospinal fluid---case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2003;43:619-625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kiecker F, Hofmann MA, Audring H, Brenner A, Labitzke C, Sterry W, Trefzer U. Large primary meningeal melanoma in an adult patient with neurocutaneous melanosis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2007;109:448-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sharouf F, Zaben M, Lammie A, Leach P, Bhatti MI. Neurocutaneous melanosis presenting with hydrocephalus and malignant transformation: case-based update. Childs Nerv Syst. 2018;34:1471-1477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jakchairoongruang K, Khakoo Y, Beckwith M, Barkovich AJ. New insights into neurocutaneous melanosis. Pediatr Radiol. 2018;48:1786-1796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kadonaga JN, Frieden IJ. Neurocutaneous melanosis: definition and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:747-755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 330] [Cited by in RCA: 267] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kang SG, Yoo DS, Cho KS, Kim DS, Chang ED, Huh PW, Kim MC. Coexisting intracranial meningeal melanocytoma, dermoid tumor, and Dandy-Walker cyst in a patient with neurocutaneous melanosis. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2006;104:444-447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ma M, Ding ZL, Cheng ZQ, Wu G, Tang XY, Deng P, Wu JD. Neurocutaneous Melanosis in an Adult Patient with Intracranial Primary Malignant Melanoma: Case Report and Review of the Literature. World Neurosurg. 2018;114:76-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Dahlberg D, Struys EA, Jansen EE, Mørkrid L, Midttun Ø, Hassel B. Cyst Fluid From Cystic, Malignant Brain Tumors: A Reservoir of Nutrients, Including Growth Factor-Like Nutrients, for Tumor Cells. Neurosurgery. 2017;80:917-924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Danial-Mamlouk C, Mamlouk MD, Handwerker J, Hasso AN. Case 220: Neurocutaneous Melanosis. Radiology. 2015;276:609-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Omar AT, Bagnas MAC, Del Rosario-Blasco KAR, Diestro JDB, Khu KJO. Shunt Surgery for Neurocutaneous Melanosis with Hydrocephalus: Case Report and Review of the Literature. World Neurosurg. 2018;120:583-589.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bekiesińska-Figatowska M, Sawicka E, Żak K, Szczygielski O. Age related changes in brain MR appearance in the course of neurocutaneous melanosis. Eur J Radiol. 2016;85:1427-1431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kim SJ, Kim JH, Son B, Yoo C. A giant congenital melanocytic nevus associated with neurocutaneous melanosis. Clin Neuroradiol. 2014;24:177-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Striano P, Consales A, Severino M, Prato G, Occella C, Rossi A, Cama A, Nozza P, Baglietto MG. A 3-year-old boy with drug-resistant complex partial seizures. Brain Pathol. 2012;22:725-728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Isiklar I, Leeds NE, Fuller GN, Kumar AJ. Intracranial metastatic melanoma: correlation between MR imaging characteristics and melanin content. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;165:1503-1512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Taylor DR, Wait SD, Wheless JW, Boop FA. Amygdalar neuromelanosis intractable epilepsy without leptomeningeal involvement. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2013;12:21-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kolin DL, Geddie WR, Ko HM. CSF cytology diagnosis of NRAS-mutated primary leptomeningeal melanomatosis with neurocutaneous melanosis. Cytopathology. 2017;28:235-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Küsters-Vandevelde HV, Willemsen AE, Groenen PJ, Küsters B, Lammens M, Wesseling P, Djafarihamedani M, Rijntjes J, Delye H, Willemsen MA, van Herpen CM, Blokx WA. Experimental treatment of NRAS-mutated neurocutaneous melanocytosis with MEK162, a MEK-inhibitor. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2014;2:41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Furtado S, Furtado SV, Ghosal N, Hegde AS. Fatal leptomeningeal melanoma in neurocutaneous melanosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:358-361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Frisoni GB, Gasparotti R, Di Monda V. Giant congenital nevus and chronic progressive ascending hemiparesis (Mills syndrome). Report of a case. Ital J Neurol Sci. 1992;13:259-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Vadoud-Seyedi R, Heenen M. Neurocutaneous melanosis. Dermatology. 1994;188:62-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Arunkumar MJ, Ranjan A, Jacob M, Rajshekhar V. Neurocutaneous melanosis: a case of primary intracranial melanoma with metastasis. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2001;13:52-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Peretti-Viton P, Gorincour G, Feuillet L, Lambot K, Brunel H, Raybaud C, Pellissier JF, Chérif AA. Neurocutaneous melanosis: radiological-pathological correlation. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:1349-1353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | de Andrade DO, Dravet C, Raybaud C, Broglin D, Laguitton V, Girard N. An unusual case of neurocutaneous melanosis. Epileptic Disord. 2004;6:145-152. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Chute DJ, Reiber K. Three unusual neuropathologic-related causes of sudden death. J Forensic Sci. 2008;53:734-738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Zhang W, Miao J, Li Q, Liu R, Li Z. Neurocutaneous melanosis in an adult patient with diffuse leptomeningeal melanosis and a rapidly deteriorating course: case report and review of the literature. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2008;110:609-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Ge P, Wang H, Zhong Y, Chen B, Ling F, Luo Y. Rare presentation in an adult patient with neurocutaneous melanosis. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1311-1313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Kurokawa R, Kim P, Kawamoto T, Matsuda H, Hayashi S, Yamazaki S, Hatamochi A, Mori S, Shimoda M, Kubota K. Intramedullary and retroperitoneal melanocytic tumor associated with congenital blue nevus and nevus flammeus: an uncommon combination of neurocutaneous melanosis and phacomatosis pigmentovascularis--case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2013;53:730-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Oliveira RS, Carvalho AP, Noro F, Melo AS, Monteiro R, Guimarães R, Landeiro JA. Neurocutaneous melanosis. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2013;71:130-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Araújo C, Resende C, Pardal F, Brito C. Giant congenital melanocytic nevi and neurocutaneous melanosis. Case Rep Med. 2015;2015:545603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Neurosciences

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Choudhery MS, Pakistan; Saito R, Japan S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ