Published online May 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i14.4594

Peer-review started: October 15, 2021

First decision: January 11, 2022

Revised: January 20, 2022

Accepted: March 25, 2022

Article in press: March 25, 2022

Published online: May 16, 2022

Processing time: 209 Days and 22.2 Hours

During the perianesthesia period, emergency situations threatening the life and safety of patients can occur at any time. When dealing with some emergencies, occasional confusion is inevitable.

This case report describes the rare situation wherein a surgeon inadvertently detached the inflatable tube of an endotracheal tube during a tonsillectomy, and positive pressure ventilation could not be provided. While reintubation may increase the risk of respiratory tract infection and aspiration, patients with a difficult airway might die due to apnea. The best treatment method is to optimize the damaged tracheal tube junction to avoid secondary intubation and ensure patient safety. An intravenous needle and cannula were used to repair the damaged gap in the current case. Following the repair, the anesthesia machine showed no indication of low tidal volume, and there was no deflation of the endotracheal tube cuff. Subsequently, the patient was transferred to the post-anesthesia recovery room, and the tracheal tube was removed with satisfactory results.

Using an intravenous needle to repair a break in the inflatable tube surrounding an endotracheal tube is safe and reliable.

Core Tip: We report a case of perianesthesia in which the trachea tube’s inflatable tube was damaged due to a surgical error, causing a ventilation disorder and triggering the anesthesia machine alarm suggesting low tidal volume. In case of an emergency, our team uses an intravenous catheter to quickly and effectively patch the inflatable tube temporarily to ensure smooth operation and patient safety.

- Citation: Wang TT, Wang J, Sun TT, Hou YT, Lu Y, Chen SG. Perianesthesia emergency repair of a cut endotracheal tube’s inflatable tube: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(14): 4594-4600

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i14/4594.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i14.4594

A perianesthesia emergency is a serious complication that cannot be predicted or prophylactically prevented during surgical anesthesia and can endanger the life and safety of the patient[1]. As anesthesia management has advanced, technologies related to artificial airways have also progressed, with specialized staff ensuring the patency of an artificial airway to protect various organs during surgery. For instance, a large number of secretions will remain in the oropharynx during oral and maxillofacial surgery. The artificial airway cuff can keep the airway closed, not only ensuring the effective implementation of positive pressure ventilation but also preventing these secretions from entering the deep airway. This is an important method of preventing ventilator-associated pneumonia[2]. It is therefore imperative that anesthesiologists manage the artificial airway cuff to avoid an emergency situation.

A 38-year-old adult male, 170 cm in height and 65 kg in weight, with recurrent episodes of throat pain for more than 2 years.

The patient’s symptoms, which involved recurrent episodes of sore throat, started 2 years prior and had worsened over the last couple of months. No fever or any other symptoms were observed.

The patient was free from any previous medical history.

The patient had no personal or family history.

After entering the operating room, venous access was established; routine monitoring, including noninvasive blood pressure, electrocardiogram, and oxygen saturation, was started; and general anesthesia was initiated. He had a pulse of 87 beats per min, arterial oxygen saturation of 100%, and a noninvasive blood pressure of 128/87 mmHg.

The patient remained hemodynamically stable with normal liver function tests, normal coagulation profile, and a hemoglobin level of 13.4 mg/dL. Electrocardiography findings were normal.

Tonsillitis was noted on laryngoscopy.

The patient was diagnosed with chronic tonsillitis.

The patient was admitted to the ambulatory surgery center of this hospital. A bilateral tonsillectomy was planned for August 8, 2021. Anesthesia drugs and products were prepared, and no abnormality was noted in the endotracheal tube cuff. Following pre-oxygenation, rapid intravenous induction of anesthesia was performed. A #6.5 endotracheal tube was inserted via laryngoscopy after complete muscle relaxation. The endotracheal tube cuff pressure was adjusted to 25 cm H2O, the tube was properly fixed, and the tube depth was recorded. Anesthesia was maintained through propofol, remifentanil, cisatracurium, and inhaled sevoflurane. Around 15 min into the surgery, the anesthesia machine alarm went off, suggesting low tidal volume. The surgery was stopped, and manual positive pressure ventilation was delivered. After checking the anesthesia machine, an endotracheal tube cuff leakage was found, which continued even after the cuff balloon was re-inflated. Upon direct inspection of the mouth, a small hole was found at a depth of 20 cm at the level of the inflatable tube. The following measures were adopted to remedy the situation: A 5 mL syringe was quickly used to insert air into the cuff balloon, and a vascular clamp was used to proximally clamp the inflatable tube to avoid air leakage from the cuff balloon and allow suctioning of nasal and oral secretions. A 22G needle was connected to the residual end of the inflatable tube, and air was injected through the needle. This allowed anesthesia machine breathing to return to normal. Intracuff pressure was measured by connecting a cuff pressure monitor to the 22G needle, with satisfactory pressure having been observed (Figure 1).

The patient was transferred to the post-anesthesia recovery room following surgery, and the endotracheal tube was removed after the patient was fully awake.

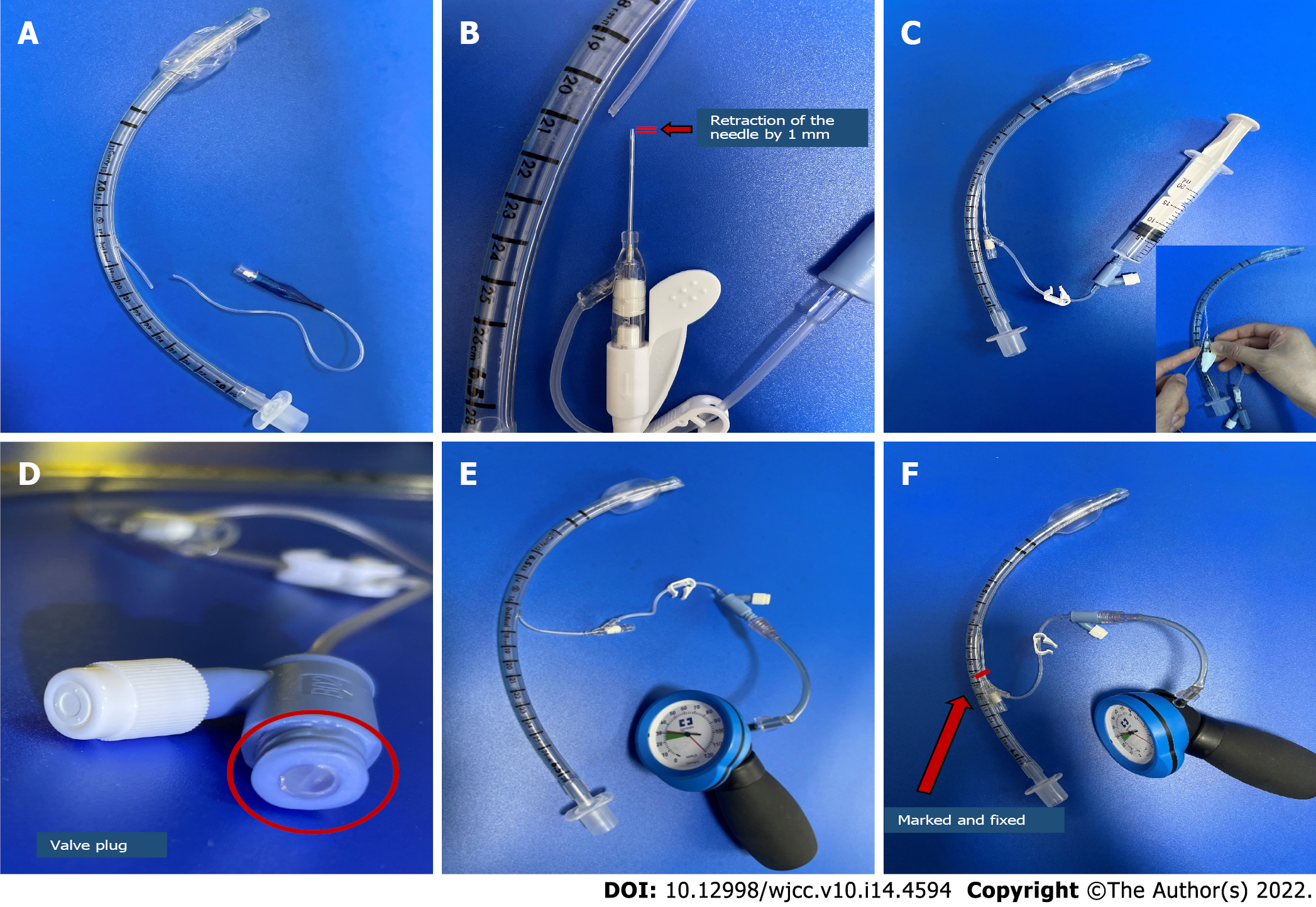

The method described herein to address such an emergency involving the inflatable tube is simple, fast, and reliable. This type of emergency requires prompt response and intervention to ensure patient safety. In the current case, we just needed an intravenous line to quickly repair and re-inflate the inflatable tube, through which we were able to address promptly address the patient’s emergency. Given that the injection end of the intravenous catheter comes with a safety-sealed valve plug, the tracheal tube cuff does not leak and can directly and accurately measure the pressure inside the cuff without the need to connect a three-way valve. The aforementioned method involved the following steps: After a rupture of the endotracheal tube inflatable tube was found (Figure 2A), the intravenous catheter was inserted into the cut end of the inflatable tube. Before inserting the needle into the broken end of the inflatable tube, the needle tip was retracted 1 mm into the cannula to avoid further damage to the inflatable tube (Figure 2B). After the intravenous catheter was inserted into the end of the inflatable tube, the needle core was removed. The intravenous catheter has a valve that can be connected to a syringe to re-inflate the cuff (Figure 2C). Thereafter, the pressure in the cuff was kept between 15 and 25 mmHg to avoid excessive pressure (Figure 2E). A transparent infusion film should be attached at the repair position and marked with a marker pen to remind medical staff to be careful during operating (Figure 2F).

Tracheal intubation under general anesthesia is an important method to ensure the patency of a patient’s airway. During the perianesthesia period, comprehensive airway and endotracheal tube cuff management is required to ensure the patient’s safety. During mechanical ventilation, cuff leakage, risk of aspiration of oral secretions and gastric contents into the airway, and excessive cuff pressure may cause damage to the airway mucosa and serious complications, such as trachea rupture[3,4].

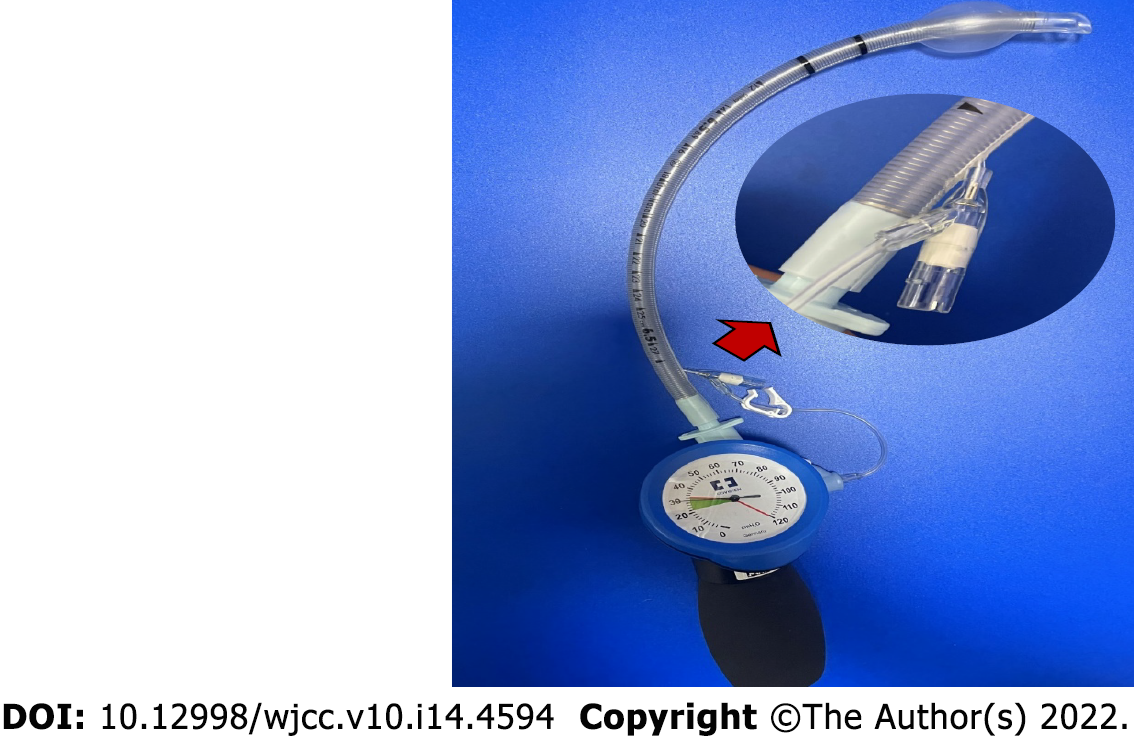

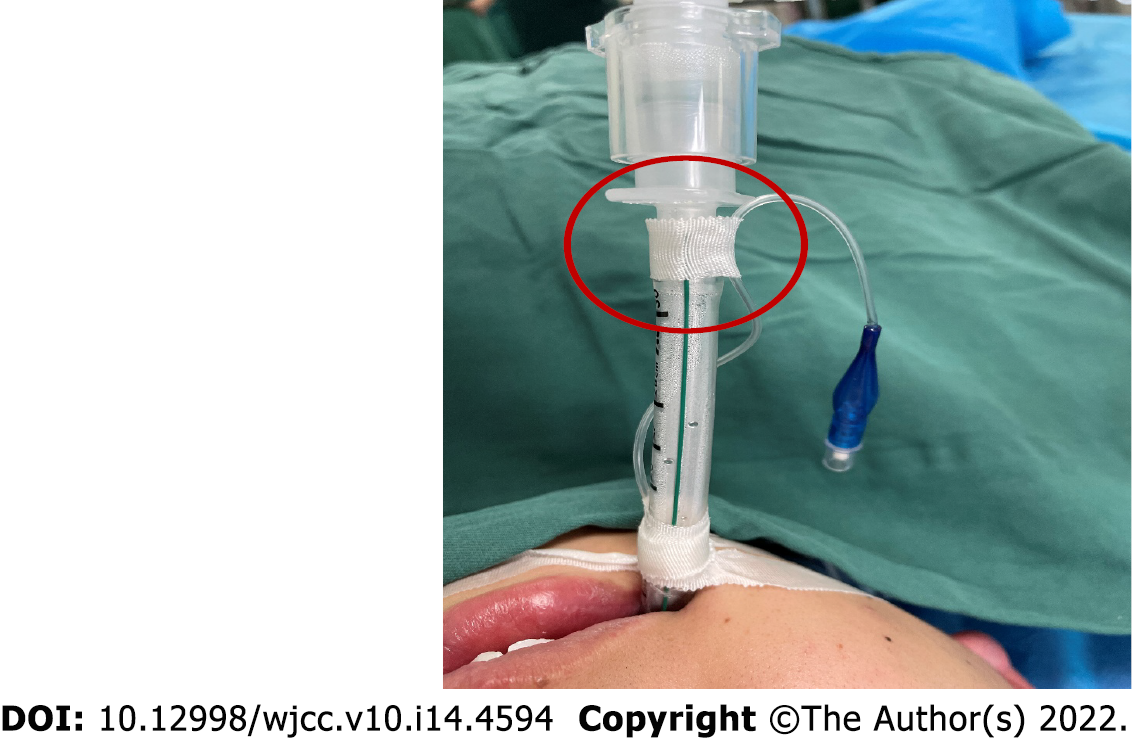

Intraoperative damage to the inflatable tube has rarely been reported in the literature. In the current case, the accidental damage to the inflatable tube during the surgical procedure could have seriously threatened the life and safety of our patient. Although the standard treatment involves replacing the tracheal tube immediately after all secretions have been sucked out, reintubation may lead to complications, including asphyxia, aspiration pneumonia, and even death. Additionally, intraoperative exchange of the endotracheal tube cuff may be difficult or impractical for patients placed in the prone position. Therefore, the health care provider must be aware of the risk of damaging the endotracheal tube’s inflatable tube during surgery and take emergency measures if it happens. In cases where the endotracheal tube’s inflatable tube is damaged, the technique described herein has been shown to maintain or increase pressure on the tracheal tube cuff. If the damage is located at the valve, this technique can be taken equally by cutting off the pilot balloon and connecting the inflatable pipe to avoid changing the pipe. Moreover, if the root of the inflatable tube is completely detached, the intravenous catheter described herein, which that can completely replace the inflatable tube and pilot balloon, can be used for rapid and effective repair to maintain endotracheal tube function (Figure 3). In addition, the intravenous catheter we used is easily obtainable in the operating room and intensive care unit and requires no three-way valve, thereby safely and quickly preventing potential airway complications. To avoid such incidents, medical staff need to take some precautions and protective measures, such as appropriately taping the pilot balloon assembly to the endotracheal tube wall to avoid cutting the inflatable tube during paramedical operations (Figure 4).

Several previous studies have described five types of cuff repair. Yoon et al[5] maintained pressure in the cuff by cutting off the middle needle stem and inserting both ends of the needle stem into the two residual ends. The disadvantages of this method include improper needle cutting, which can cause the tip to become completely blocked or the lumen to be too narrow to fill adequately the cuff. In addition, if the cut end is sharp, the needle may easily puncture the inflatable cuff. Given the small size of the parts, connecting the needle stem to the stump is difficult, and errors in its implementation carry safety risks for patients. Furthermore, the device is not widely available and should not be used during magnetic resonance imaging examinations. Emergency repair of the cuff takes a long time with this method and increases the workload of the medical team. In Sprung et al[6], the needle core of the scalp needle was obtained to meet the pressure in the cuff, with the potential complications being consistent with the approach described by Yoon et al[5]. Whiteside and Exler[7] used a syringe to replenish the cuff gas and a vascular clamp to clamp the inflatable tube to maintain cuff pressure. In Dayan and Epstein[8], the inflatable tube was inserted into each stump by cutting the hose in the intravenous catheter to maintain pressure inside the cuff. The disadvantage of this method is that it is difficult to connect the two ends intraoperatively given the lack of tube core support. Moreover, improper implementation can be dangerous to the patient. Owusu-Bediako et al[9] directly connected the residual end of the tracheal cuff balloon using a 24G intravenous cannula and then connected the cannula to a three-way valve in order to fill the balloon. The disadvantages of this method include the need for complicated materials, such as a three-way valve. Furthermore, it is necessary to operate the three-way valve to measure the endotracheal tube cuff pressure.

All of the aforementioned methods have some difficulties, including complicated operation, complex sampling, and an increased workload for the medical team. Hao et al[10]reported a case latest and described the use of an angio-catheter to connect a ruptured endotracheal tube’s inflatable tube while also installing a clave on the angio-catheter to maintain cuff pressure. While the method is satisfactory, it requires the use of a clave. By contrast, our method is convenient, rapid, and effective in shortening the time needed to address the patient’s emergency.

Nonetheless, there are some limitations to this method. First, the inner diameter of the inflatable cuff on an endotracheal tube is not standardized; thus, different diameters of venous catheters may be needed. Second, this method cannot be used when the rupture of the cuff tube is deep and cannot be directly visualized. Again, given that the tension of the repaired inflatable tube will not be firm, the use of transparent tape to fix the fracture is recommended. The final patch changed the appearance of the pilot balloon assembly. Moreover, given that the technique is used in intensive care units or during anesthesia, needle wound complications may occur in uncooperative patients undergoing repair work in the presence of agitation. Thus, the patient may need to be appeased, and in severe cases, drugs may be needed for sedation.

The method described herein, which involved using an intravenous needle to repair a break in the inflatable cuff surrounding an endotracheal tube, is safe and reliable. No re-leakage of the cuff was observed after the repair, which eliminated the risk of a second intubation and reduced the workload of medical staff. Moreover, the materials are convenient, and the method is simple and rapid, which reduce the patient’s physical and mental trauma and the occurrence of medical disputes.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Anesthesiology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Amornyotin S, Thailand; Deshwal H, United States; Kokot A, Croatia S-Editor: Guo XR L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Guo XR

| 1. | Gaba DM, Maxwell M, DeAnda A. Anesthetic mishaps: breaking the chain of accident evolution. Anesthesiology. 1987;66:670-676. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Lorente L, Lecuona M, Jiménez A, Mora ML, Sierra A. Influence of an endotracheal tube with polyurethane cuff and subglottic secretion drainage on pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:1079-1083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Liu J, Zhang X, Gong W, Li S, Wang F, Fu S, Zhang M, Hang Y. Correlations between controlled endotracheal tube cuff pressure and postprocedural complications: a multicenter study. Anesth Analg. 2010;111:1133-1137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fan CM, Ko PC, Tsai KC, Chiang WC, Chang YC, Chen WJ, Yuan A. Tracheal rupture complicating emergent endotracheal intubation. Am J Emerg Med. 2004;22:289-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yoon KB, Choi BH, Chang HS, Lim HK. Management of detachment of pilot balloon during intraoral repositioning of the submental endotracheal tube. Yonsei Med J. 2004;45:748-750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sprung J, Bourke DL, Thomas P, Harrison C. Clever cure for an endotracheal tube cuff leak. Anesthesiology. 1994;81:790-791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Whitesides LM, Exler AS. Intraoperative damage and correction of pilot balloon during orthognathic surgery. Anesth Prog. 1997;44:38-39. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Dayan AC, Epstein RH. Structural Integrity of a Simple Method to Repair Disrupted Tracheal Tube Pilot Balloon Assemblies. Anesth Analg. 2016;123:1158-1162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Owusu-Bediako K, Turner H 3rd, Syed O, Tobias J. Options for Intraoperative Repair of a Cut Pilot Balloon on the Endotracheal Tube. Med Devices (Auckl). 2021;14:265-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hao D, Johnson JJ, Patel SS, Liu CA. Technique to manage intraoperative cuff leak from damaged endotracheal tube pilot balloon. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021;50:1588-1590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |