Published online Apr 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i12.3959

Peer-review started: December 7, 2021

First decision: January 25, 2022

Revised: January 29, 2022

Accepted: March 6, 2022

Article in press: March 6, 2022

Published online: April 26, 2022

Processing time: 135 Days and 7.3 Hours

Kissing molars (KMs) are a scarcely reported form of molar impaction in which the occlusal surfaces contact each other within a single dental follicle and the roots point in opposite directions. The direction of KMs impaction is generally tilted. KMs with vertical direction impaction have not been reported in the literature.

A 25-year-old female visited a dentist for right maxillary wisdom teeth extraction and was diagnosed with two vertically impacted KMs in the left mandible on panoramic radiography. After cone-beam computed tomography examination confirmed no secondary complication, the patient chose to undergo observation and regular follow-up. A literature review of KMs revealed that vertical impacted KMs are rare; high-quality evidence regarding their prevalence is still lacking. At present, the causality of KMs is controversial. In this study, we have tried to provide a detailed definition of KMs to allow an accurate evaluation of their prevalence and classification based on their impaction direction which may be related to their pathogenesis. The treatment plan of KMs depends on the condition and location of the affected teeth and associated complications; they may be either directly extracted or treated using a multidisciplinary approach including maxillofacial surgeons and orthodontists.

KMs are a rare clinical condition of impacted teeth with unclear pathogenesis. Vertically impacted KMs were seldom reported. Reasonable definition and classification of KMs can help in the understanding of their causes and prevalence.

Core Tip: Kissing molars (KMs) are a rare type of impacted teeth. This study reported a case of KMs with a vertical impaction direction which was different from those of previous cases. Despite the unclear pathogenic mechanism, they cause secondary complications such as cysts and other odontogenic tumors; hence, they should be actively treated by a multi-disciplinary team. Reasonable definition and classification of KMs can help us to better understand their causes and prevalence.

- Citation: Wen C, Jiang R, Zhang ZQ, Lei B, Yan YZ, Zhong YQ, Tang L. Vertical direction impaction of kissing molars: A case report . World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(12): 3959-3965

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i12/3959.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i12.3959

The term kissing molars (KMs) refers to a rare molar impaction disease[1] in which the occlusal surfaces contact each other within a single dental follicle and the roots point in opposite directions. The condition generally shows in the lower jaw as an impaction. Essentially, KMs are considered specially formed supernumerary and impacted teeth. The impacted position and the involved teeth may vary and their etiology is unclear.

In this study, we report for the first time a rare type of KMs, vertically impacted and pointing in opposite directions. We reviewed the available literature in the PubMed database to analyze the classification and possible pathological causes of KMs to provide data and recommendations for dealing with such cases. The search terms were” kissing molars” OR” rosette formation” OR” cuddling tooth.” Article titles and abstracts were screened to find reports related to this topic and the full texts of eligible articles were reviewed.

The existing definition of KMs is limited to their morphological features and their inclusion criteria are not strict in some reports. Furthermore, the existing classification of KMs is unclear and only based on teeth numbering without considering the impaction situation and position. Therefore, it is necessary to impose more accurate restrictions on the morphological definition of KMs. In addition, we attempted to classify KMs according to their direction.

The patient was a female of Han ethnicity aged 25 years; she visited the People’s Hospital of Aba Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture for treatment of the right maxillary wisdom tooth.

The patient was in good health; the left maxillary wisdom tooth had been extracted.

The patient had no history of trauma, serious or metabolic diseases.

The patient denied any relevant personal or family history.

Oral examination showed good oral hygiene except for mesial caries in the right maxillary wisdom tooth due to food impaction.

The routine blood count and coagulation profile were within normal limits.

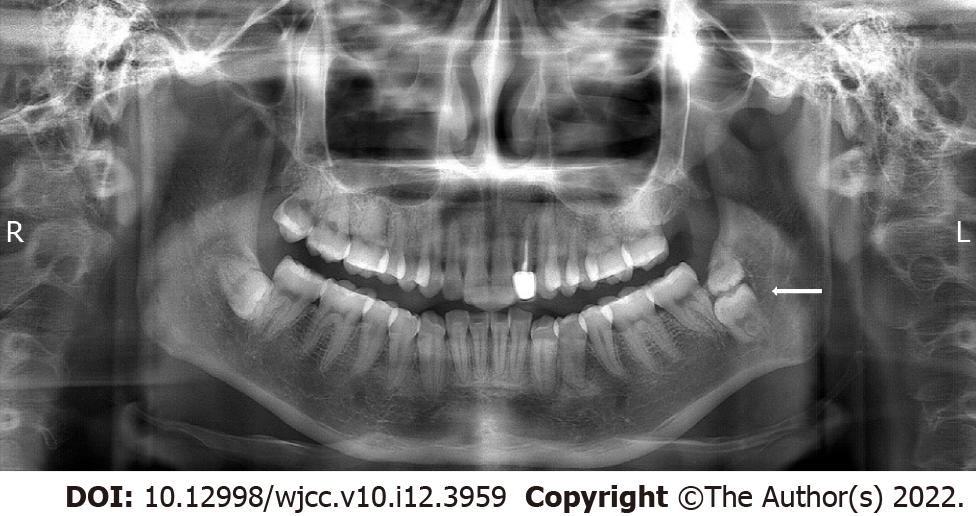

A panoramic radiograph showed that apart from the horizontally impacted #32, there were two impacted molars pointing in opposite directions distal to the second molar in the left mandible. According to the tooth morphology and the Universal Numbering System, we inferred that the tooth in the lower position was #17 and the tooth in the higher position was the supernumerary fourth molar #67. The occlusal surfaces of the two teeth completely coincided and were opposite to each other in the vertical direction (Figure 1).

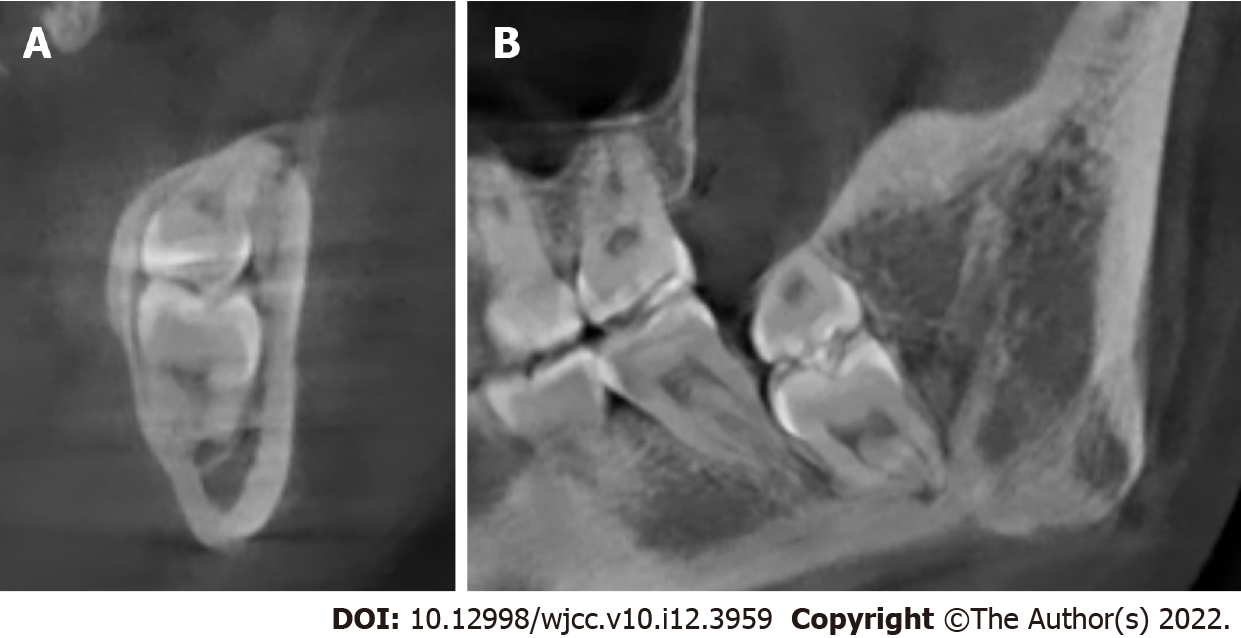

We then examined the patient using cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT). CBCT revealed bone resorption on the lingual side and sharp proximity of tooth #17 to the inferior alveolar nerve. The occlusal surfaces of teeth #17 and #67 were in close contact and the distal bone of tooth #18 was absorbed; no other complications were observed (Figure 2).

KMs involving teeth #17 and #67.

After the examination, the patient was advised to have the KMs and other impacted teeth removed. After fully informing the patient of the benefits and risks of treatment, the patient accepted removal of tooth #1 and refused the removal of both KMs and the impacted tooth #32, choosing instead to undergo observation and regular follow-up.

KMs are a rare form of impacted teeth first reported by Van Hoof et al[1] in 1973. Other scholars used different terms to describe the condition; Nakamura et al[2] referred to it as “rosette formation,” while Agarwal et al[3] used the term “cuddling tooth.” Since there is no standard naming system for this condition, in this report, we used the term “kissing molars” as originally described.

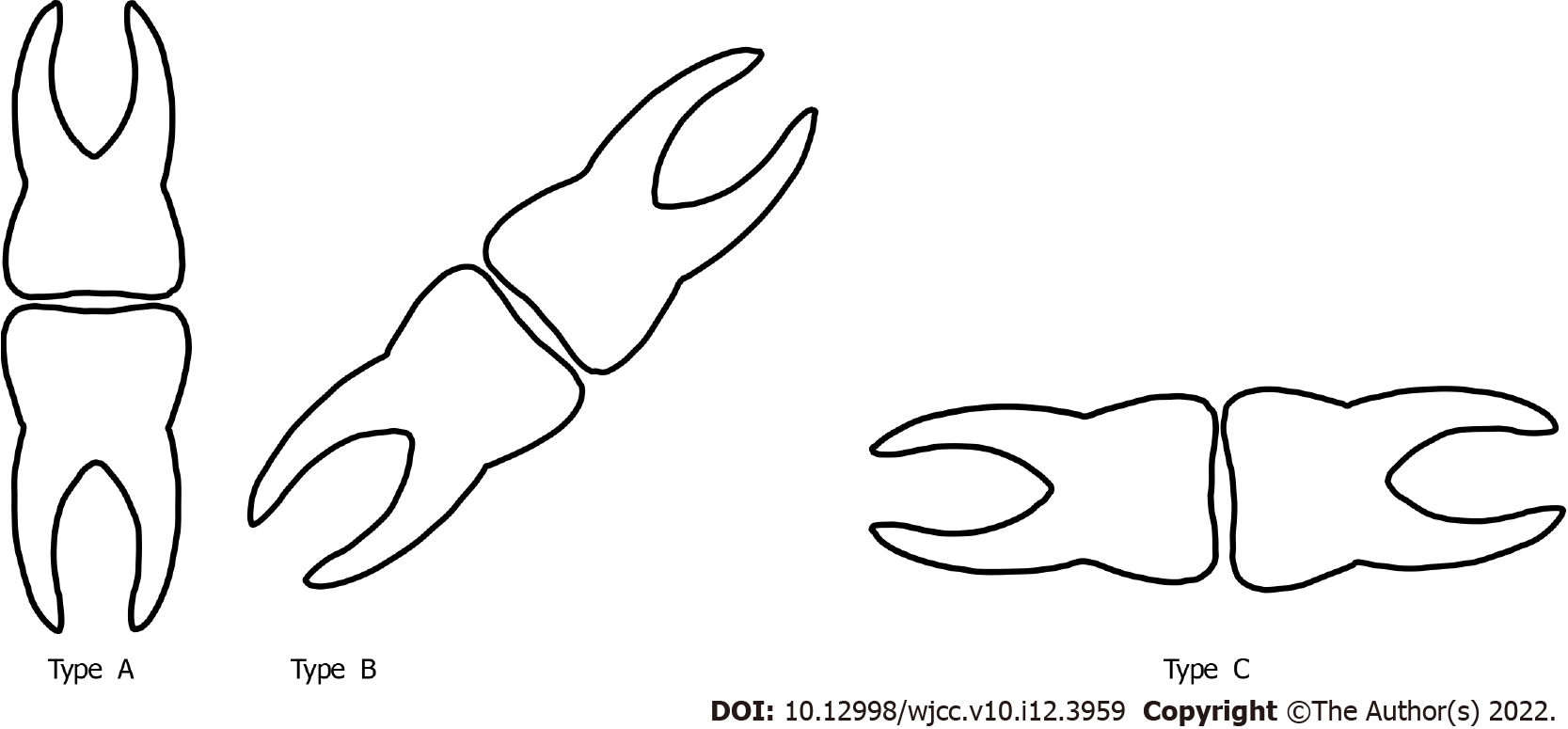

Most reported KMs occur in the mandibular molar area. The classification of KMs by Gulses et al[4] indicated that according to the tooth position, KMs can be divided into three different types: first and second molars (Class I), second and third molars (Class II) and third and fourth molars (Class III). Although this classification method is relatively imprecise, there is no other widely accepted classification. In this study, we tried to classify KMs by the teeth’s impacted direction, which can include the complete vertical direction (Type A), tilted direction (Type B) and complete horizontal direction (Type C, Figure 3). In Type A, the root side teeth could originally erupt normally despite being impacted, whereas Type B shows a slight axial dislocation of both teeth, or slight axial dislocation of one tooth and severe axial dislocation of the other and Type C shows severe transverse dislocation of both teeth. Although this classification method still does not cover all possibilities, it may better reflect the causes and severity of axial dislocation which are related to the difficulty of extraction, treatment strategies and incidence of complications.

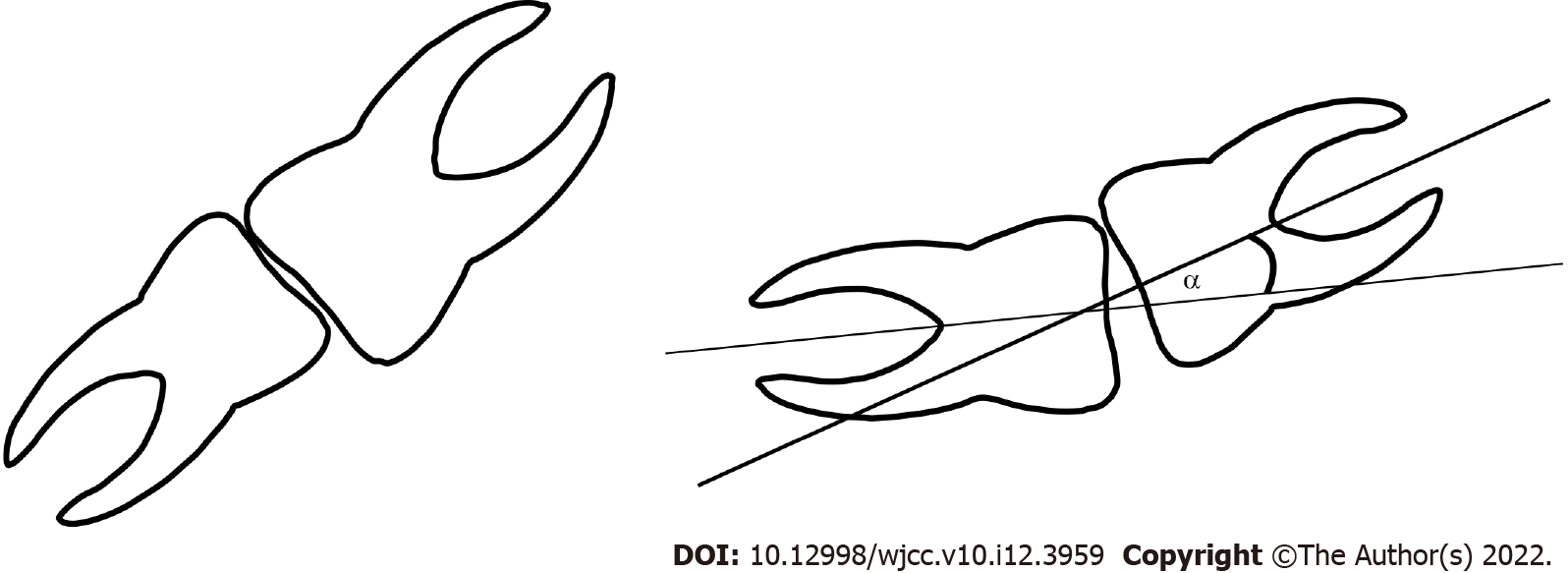

Owing to the low prevalence of KMs, most literature includes only case reports and studies on the prevalence from large sample sizes are rare. However, studies used different definitions and inclusion criteria. Some studies have reported teeth in which the occlusal surfaces slightly overlap should only be regarded as ordinary impacted teeth rather than KMs. Therefore, the real prevalence rates of KMs remain unclear. We believe that the overlapping region of the occlusal surfaces and the acute angle formed by the long axis of the two teeth should be considered when identifying KMs (Figure 4).

Yanik et al[5] reported a prevalence rate of KMs of 0.06% in a large sample size of 6,570 Turkish individuals, without significant differences between men and women. However, according to their images, at least 1 case did not seem to be that of KMs in the strict sense, which was more like teeth with severe tilt. Gulses et al[4] found nine KMs among 2,381 patients with impacted third molars (0.37%); however, the included participants in this study were not ordinary people but patients with impacted molars, conforming a significantly different population from that in Yanik et al[5]’s study. Thus, although the studies included large populations, their heterogeneity precluded direct comparisons or data merging.

KMs may occur alone or there could be multiple KMs in 1 individual, either unilateral or bilateral[6]. The potential complications caused by KMs are related to the teeth location and their relationship with the adjacent teeth, including root resorption, adjacent tooth caries, ectopic eruption and dentition crowding, as well as odontoma, periodontal diseases, progressive bone resorption and cystic lesions such as dentigerous cyst, etc.[5,7,8].

Currently, the causes of KMs are equivocal. Some researchers believe that the occurrence of KMs is an independent event due to the abnormal development of adjacent tooth germs. During molar development from a lower position, contact and impaction with distal molar germs may lead to an abnormal growth direction of tooth germs resulting in abnormal teeth eruption direction and eventually KMs formation[9]. Some scholars hypothesized that bone resorption caused by cysts leads to KMs. Krishnan et al[10] believed that cyst swelling may lead to mesial bone resorption of the impacted teeth resulting in tooth migration, rotation and displacement. However, bone resorption caused by cystic lesions does not always occur in KMs. Therefore, the relationship between KMs and cystic lesions may be due to KMs causing cystic lesions rather than the other way around. Additionally, Kiran et al[11] correlated hyperplastic dental follicle (HDF) with KMs; with the proliferation of dental follicles, HDF disease would expand the follicles around the unerupted crown by about 3-5 mm and the enlarged dental follicles may then affect the eruption direction of the distal teeth.

On the other hand, some scholars believe that the formation of KMs is related to systemic diseases. Nakamura et al[2] studied 4 patients with mucopolysaccharidosis (MPS), in which panoramic radiographs showed that 3 had KMs. Therefore, Nakamura et al[2] concluded that KMs may be associated with MPS. Similarly, two other studies reported impacted molars just like KMs with MPS[12] or Gargoylism (MPS type I)[13]. Therefore, it was proposed that MPS may affect the connective and bone tissue surrounding the tooth germ, lock the crown during tooth germ development, impact normal tooth eruption and affect the tooth development direction[14]. However, in this case, the personal and family history showed that the patient and her family did not present with MPS or other systemic diseases. Simultaneously, other reports have shown that KMs mostly occur in patients without systemic diseases and do not see a direct association with these diseases. Therefore, MPS and other connective tissue diseases may just be some of the factors inducing KMs.

The treatment plan for KMs depends on the condition and location of the affected teeth[15,16]. Affected teeth which cannot be retained or show complications, should be removed promptly[17]. Teeth with therapeutic value can be retained, for instance, in KMs TYPE A, the lower tooth may sprout to the normal position through natural eruption or orthodontic traction after removing resistance of the upper impacted tooth[18,19]. While devising a tooth extraction plan, protecting the neurovascular bundle with minimally invasive techniques should be considered. Additionally, the presence of cystic disease, root absorption of adjacent teeth, root shape and tightness of contacting teeth should be considered[20]. The surgical approach for KMs extraction requires an exhaustive understanding of the anatomy of this region, advanced surgical abilities and rigorous planning[21]. The impaction depth is the main factor affecting tooth extraction. In Type A and B KMs, the lower tooth is relatively more difficult to extract because of their deep position and proximity to the nerve. For Type C KMs, the difficulty is mainly determined by its embedding depth. The deeper the embedding depth, the more bone needs to be removed. Additionally, because of the large volume of the two impacted teeth, especially when combined with bone absorption formed by cystic lesions, fracture caused by fragile structure of the remaining mandible should be avoided during the extraction process[22]. When the area around KMs is accompanied by dilated cystic shadow in radiography, it is necessary to distinguish whether it is a proliferative dental follicle, dentigerous cyst, keratocyst, ameloblastoma or other cystic or malignant lesions, and treat it from a multidisciplinary perspective.

KMs are rare and complex impacted teeth of unclear etiology. Vertically impacted KMs were seldom reported. Proper classification and definition are essential for accurate clinical diagnosis and appropriate treatment. Further research is needed to evaluate both their etiology and treatment management strategies.

The author Cai Wen thanks the warm and kind Tibetan and Qiang people of Ma’erkang for their assistance during his 1-year health poverty alleviation work. Thanks also to Hua-Jun Jing, Zhao-Zhong Tu, Yun-Fei Liu and Chun-Yi Xu from Sichuan Academy of Medical Sciences and Sichuan Provincial People's Hospital for their help during that difficult time.

| 1. | Van Hoof RF. Four kissing molars. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1973;35:284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Nakamura T, Miwa K, Kanda S, Nonaka K, Anan H, Higash S, Beppu K. Rosette formation of impacted molar teeth in mucopolysaccharidoses and related disorders. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1992;21:45-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Agarwal A, Mittal G, Uppada UK. Cuddling Teeth: A New Terminology. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2019;9:53-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gulses A, Varol A, Sencimen M, Dumlu A. A study of impacted love: kissing molars. Oral Health Dent Manag. 2012;11:185-188. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Yanik S, Ayranci F, İşman Ö, Büyükçikrikci Ş, Aras MH. Study of kissing molars in Turkish population sample. Niger J Clin Pract. 2017;20:659-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nedjat-Shokouhi B, Webb RM. Bilateral kissing molars involving a dentigerous cyst: report of a case and discussion of terminology. Oral Surg. 2014;7:107-110. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Matzen LH, Schropp L, Spin-Neto R, Wenzel A. Radiographic signs of pathology determining removal of an impacted mandibular third molar assessed in a panoramic image or CBCT. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2017;46:20160330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Demiriz L, Durmuşlar MC, Mısır AF. Prevalence and characteristics of supernumerary teeth: A survey on 7348 people. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2015;5:S39-S43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Shahista P, Mascarenhas R, Shetty S, Husain A. Kissing molars: An unusual unexpected impaction. Arch Med Health Sci. 2013;1:52-53. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Krishnan B. Kissing molars. Br Dent J. 2008;204:281-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kiran HY, Bharani KS, Kamath RA, Manimangalath G, Madhushankar GS. Kissing molars and hyperplastic dental follicles: report of a case and literature review. Chin J Dent Res. 2014;17:57-63. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Cavaleiro RM, Pinheiro Md, Pinheiro LR, Tuji FM, Feio Pdo S, de Souza IC, Feio RH, de Almeida SC, Schwartz IV, Giugliani R, Pinheiro JJ, Santana-da-Silva LC. Dentomaxillofacial manifestations of mucopolysaccharidosis VI: clinical and imaging findings from two cases, with an emphasis on the temporomandibular joint. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2013;116:e141-e148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cawson RA. The oral changes in gargoylism. Proc R Soc Med. 1962;55:1066-1070. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Menditti D, Laino L, Cicciù M, Mezzogiorno A, Perillo L, Menditti M, Cervino G, Lo Muzio L, Baldi A. Kissing molars: report of three cases and new prospective on aetiopathogenetic theories. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:15708-15718. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Udagawa G, Kataoka T, Amemiya K, Kina H, Okamoto T. Bilateral kissing molars involving a dentigerous cyst: A case report and literature review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Med Pathol. 2022;34:40-44. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Singh G, Daga D, Vignesh U, Agrawal R. Unusual location of molars called as kissing molars: A case report. Int J Oral Health Dentist. 2018;4:49-51. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Boffano P, Gallesio C. Kissing molars. J Craniofac Surg. 2009;20:1269-1270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Almpani K, Kolokitha OE. Role of third molars in orthodontics. World J Clin Cases. 2015;3:132-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Dhuvad JM, Kshirsagar RA. Impacted love: mandibular kissing molars advisable to remove or not. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:ZL01. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Nakamori K, Tomihara K, Noguchi M. Clinical significance of computed tomography assessment for third molar surgery. World J Radiol. 2014;6:417-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Arjona-Amo M, Torres-Carranza E, Batista-Cruzado A, Serrera-Figallo MA, Crespo-Torres S, Belmonte-Caro R, Albisu-Andrade C, Torres-Lagares D, Gutiérrez-Pérez JL. Kissing molars extraction: Case series and review of the literature. J Clin Exp Dent. 2016;8:e97-e101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kouhsoltani M, Mesgarzadeh AH, Moradzadeh Khiavi M. Mandibular Fracture Associated with a Dentigerous Cyst: Report of a Case and Literature Review. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospects. 2015;9:193-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Committeeman (youth) of Geriatric Stomatology of Chinese Stomatological Association; Committeeman of Sichuan Provincial Committee of Oral Implantology; and Committeeman of Sichuan Provincial Committee of Oral Genetics.

Specialty type: Dentistry, oral surgery and medicine

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Primadhi RA, Indonesia; Soni S, United States S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Gong ZM