Published online Apr 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i12.3886

Peer-review started: September 11, 2021

First decision: October 25, 2021

Revised: November 1, 2021

Accepted: March 6, 2022

Article in press: March 6, 2022

Published online: April 26, 2022

Processing time: 222 Days and 8.1 Hours

Giant renal angiomyolipomas (AMLs) may lead to complications including flank pain, hematuria, hypertension, retroperitoneal hemorrhage and even death. Giant AMLs which grow around renal hilar vessels and the ureter are rare. Most previous reports on the treatment of giant renal AMLs have focused on open surgery or a transperitoneal approach, with few studies on the retroperitoneal approach for large AMLs. We here report a case of giant renal hilum AML successfully treated with robot-assisted laparoscopic nephron sparing surgery the retroperitoneal approach, with a one-year follow-up.

A 34-year-old female patient was diagnosed with renal AML 11 years ago and showed no discomfort. The tumor gradually increased in size to a giant AML over the years, which measured 63 mm × 47 mm ×90 mm and was wrapped around the right hilum. Therefore, a robotic laparoscopic partial nephrectomy (LPN) via the retroperitoneal approach was performed. The patient had no serious postoperative complications and was discharged soon after the operation. At the one-year follow-up, the patient's right kidney had recovered well.

Despite insufficient operating space via the retroperitoneal approach, LPN for giant central renal AMLs can be completed using a well-designed procedure with the assistance of a robotic system.

Core Tip: Renal angiomyolipoma (AML) is an infrequent benign tumor, and treatment includes open surgery or a transperitoneal laparoscopic nephrectomy (LPN). Despite several disadvantages, the retroperitoneal (RP) approach enables direct access to the renal artery and does not require bowel mobilization, which may avoid gastrointestinal complications and shorten recovery time. We report a patient with renal AML who underwent successful robot-assisted LPN using the RP approach. The patient was discharged from hospital on the 4th postoperative day and one-year follow-up showed no recurrence. This case highlights the feasibility of RP LPN with a well-designed surgical procedure, and the advantages of this method outweigh the disadvantages in AML patients.

- Citation: Luo SH, Zeng QS, Chen JX, Huang B, Wang ZR, Li WJ, Yang Y, Chen LW. Successful robot-assisted partial nephrectomy for giant renal hilum angiomyolipoma through the retroperitoneal approach: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(12): 3886-3892

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i12/3886.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i12.3886

Renal angiomyolipoma (AML) is an infrequent benign tumor consisting of spindle and epithelioid smooth muscle tissue, mature adipose tissue and blood vessels. Furthermore, a large AML which grows around renal hilar vessels and the ureter is rare. Laparoscopic partial nephrectomy (LPN) is the standard and ultimate solution for renal AML (especially AMLs greater than 4 cm[1]), and two approaches are usually used: the transperitoneal (TP) and retroperitoneal (RP) approach[2]. While the former provides a larger working space, allowing a wider angle to reach tumors, the latter enables direct access to the renal artery and does not require bowel mobilization[3]. However, when confronted with a relatively large AML, laparotomy is a better choice. We herein report a female patient with a giant central renal AML which had grown around the right hilum. Robot-assisted LPN via the RP approach as well as laparoscopic aspiration were performed[4]. The patient had a satisfactory outcome at one-year follow-up.

A 34-year-old female patient was admitted to our department with an 11-year history of a growing hamartoma on the right kidney.

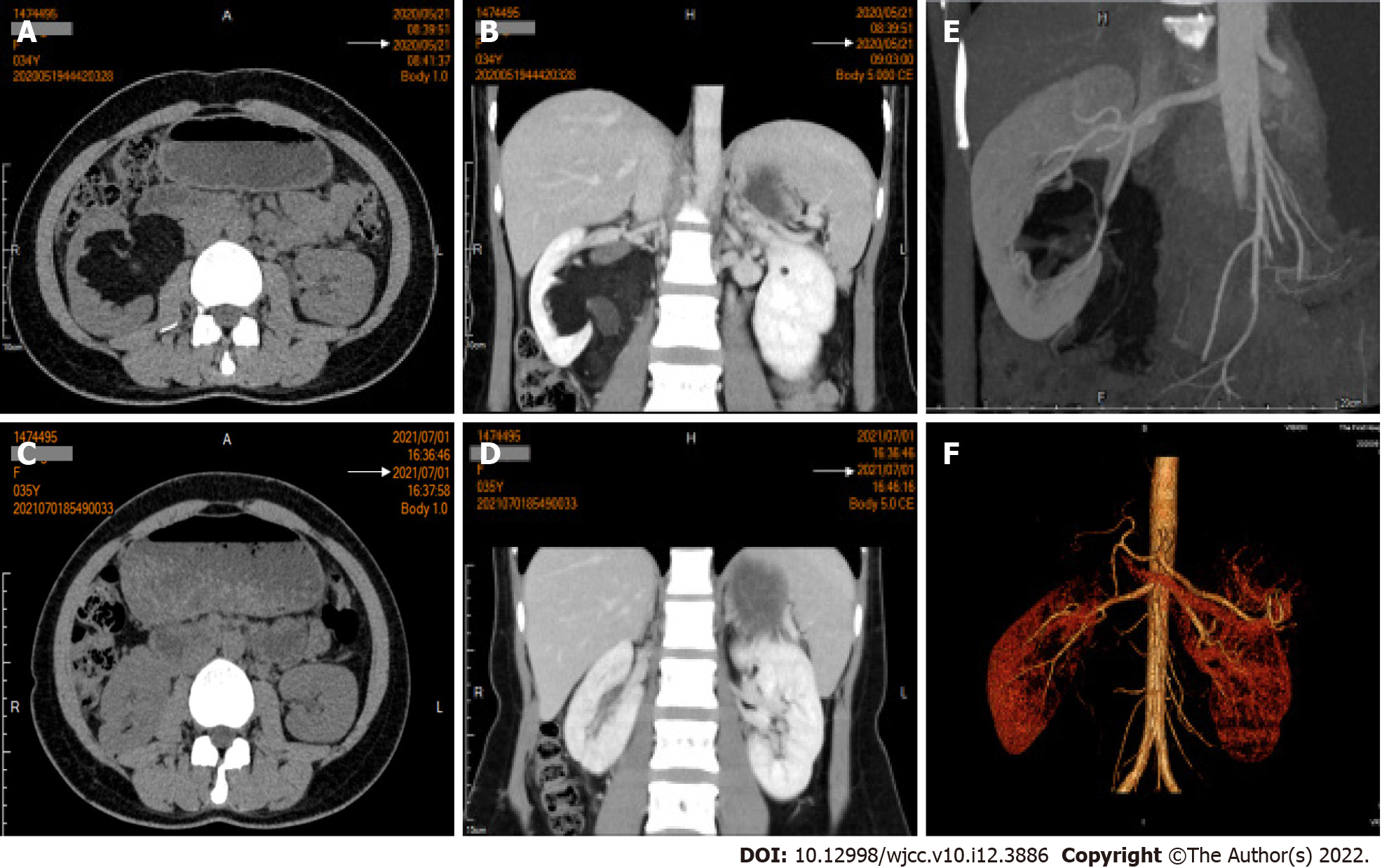

The tumor was detected accidentally during a physical examination 11 years ago and quickly diagnosed as renal AML. The patient did not present any discomfort, and the tumor showed no malignant tendency. Therefore, the patient chose to undergo regular follow-up rather than surgical treatment. Approximately two weeks before admission to our hospital, imaging examination revealed that the mass had grown to 9 cm in maximum diameter, and was wrapped around the right hilum (Figure 1A and B).

The patient had no previous medical history, and there was no history of genetic disease or renal AMLs in her family.

None.

On admission, the patient‘s temperature was 36.5℃, heart rate was 84 bpm, respiratory rate was 20 breaths/min, and blood pressure was 128/79 mmHg. The abdomen was supple without masses or organomegaly, and no renal tenderness or percussed pain was observed.

Routine blood tests revealed a red blood cell count of 4.34x109/L and hemoglobin level of 131 g/L. Prothrombin and partial thromboplastin times were normal. The results of blood biochemistry tests were within the normal ranges. Serum creatinine level was 53 μmol/L and blood urea nitrogen level was 3.7 mmol/L, demonstrating normal renal function. Electrocardiogram and chest X-ray were also normal.

Approximately two weeks before admission, a contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) examination revealed that the tumor had grown from the hilum to lower part of the right kidney, measuring 90 mm × 47 mm × 65 mm, and was wrapped around the right hilum (Figure 1A and B), and the scope of scanning did not reach the pelvic cavity. Bilateral renal CT angiography revealed that the middle and lower branches of the right renal artery were involved (Figure 1E).

Giant renal AML of the right kidney.

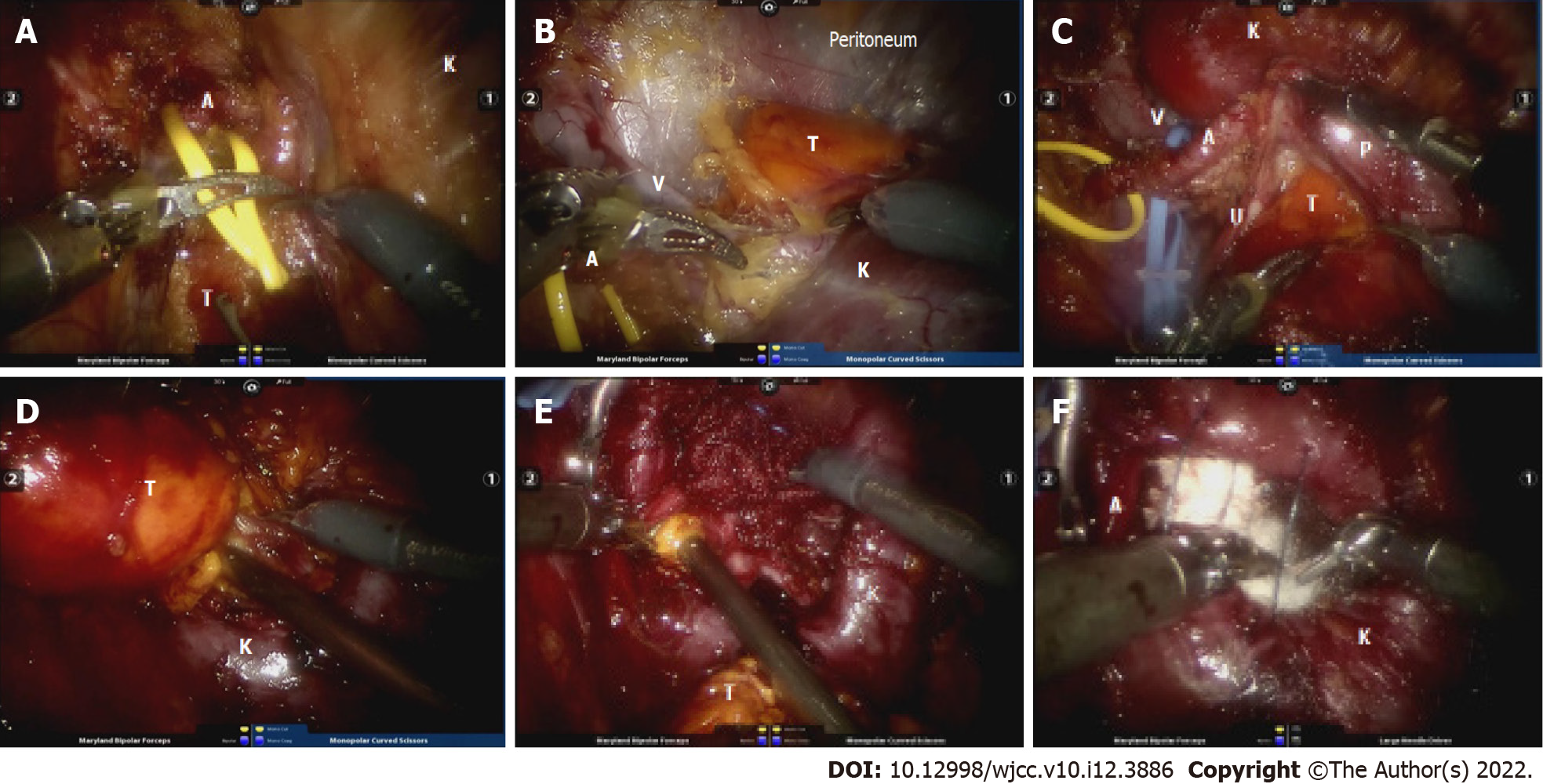

In view of the recent rapid growth of the tumor, the increased risk of rupture and hemorrhage, and the increased compression on the hilum, the patient underwent surgery. With the hope that the right kidney could be preserved, a well-designed robotic RP LPN was performed. Under general anesthesia, the patient was placed in the lateral decubitus position with hyperextension. The RP space was established according to the routine method mentioned in previous reports[2]. After removing RP fat and opening the renal fascia, dissection was performed along the psoas muscle to the postcava and the right ureter was carefully exposed as follows: (1) Renal artery dissociation (Figure 2A): Dissection continued along the ureter until the right renal artery was dissociated. A vessel sling was used to mark the renal artery when it was fully exposed; (2) Full kidney dissociation and renal vein exposure (Figure 2B): From dorsal to ventral, the right kidney was fully dissociated from perinephric fat. When the kidney was thoroughly dissociated from the surrounding tissue, the renal vein was carefully exposed through a good viewpoint, from dorsal to ventral, which was also marked by a sling; (3) Initial tumor exposure around the hilum and ureter dissociation (Figure 2C): Fat covering the surface of the tumor was removed to distinguish the periphery of the mass. Simultaneously, dissociation of the upper pole of the right ureter was performed as far as the renal pelvis, which was closely attached to the mass. The ureter could then also be towed by a sling if needed. Great care was taken during this step, in order to avoid disruption of the tumor capsule and renal capsule which could lead to hemorrhage. Hence, the ureter and renal vessels were thoroughly dissected; (4) Further separation of the AML (Figure 2D): The renal artery was clamped with a bulldog clamp. The mass was then further separated from the kidney and resected along its base using an electric scalpel; and (5) Tumor base and wound fossa management (Figure 2E and F): The suction device was inserted into the renal defect, followed by thorough aspiration of the tumor base and remaining tumor tissue step by step. Small vessels in the defect were ligated and the wound fossa was packed with five pieces of absorbable hemostatic gauze (SurgicelTM, Johnson and Johnson, United States). Before placement of the hemostatic gauze, the 2-0 V-Loc absorbable wound closure device was loaded without tightening up. After pressing on the tamping for 3 min as coagulation time, the defect was tightly closed. This bleed-arresting strategy has been used in clinical practice for a long time and has proved effective.

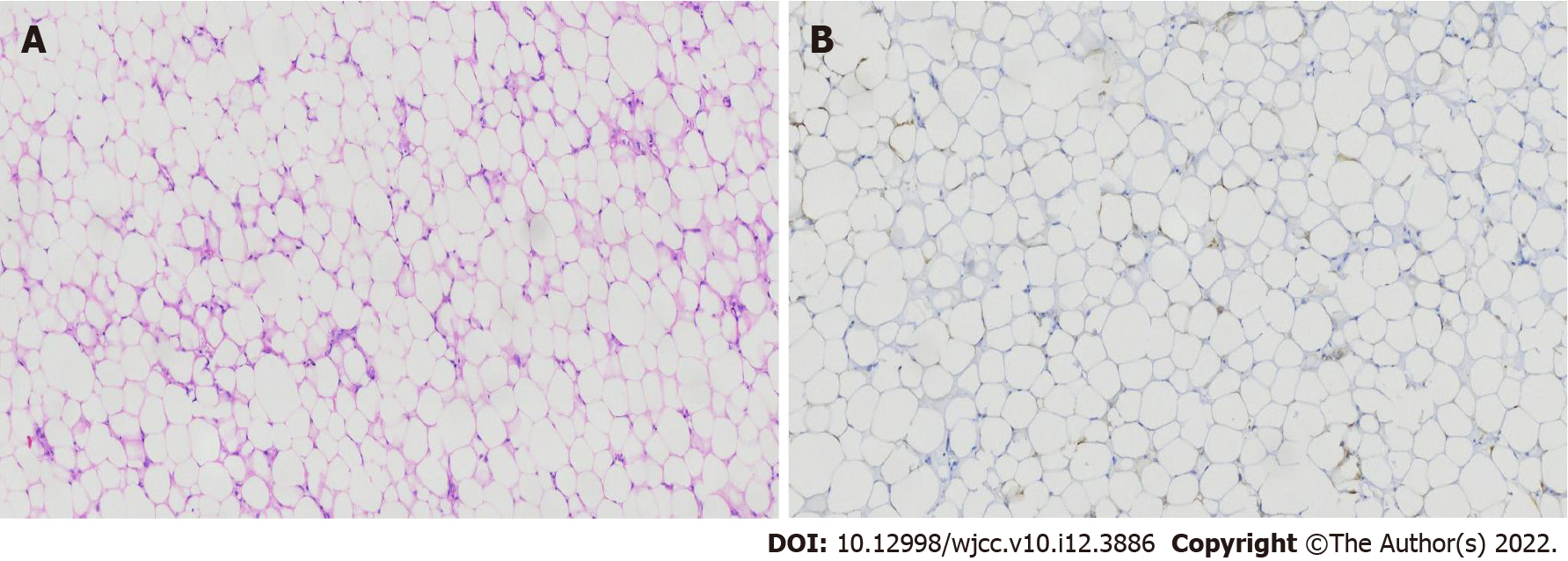

Histopathological examination of the specimen revealed that the majority of cells were mature adipocytes, and there was a pattern with typical fat and perivascular epithelioid cells arranged around blood vessels, supporting the diagnosis of AML (Figure 3). The patient recovered uneventfully and was discharged from our hospital on the 4th postoperative day. At one-year follow-up, there was no evidence of tumor recurrence and the right kidney was observed to have recovered well on a recent imaging evaluation (Figure 1C and D).

Previous studies have revealed that renal AML may grow by 4 cm each year in its maximum dimension[5]. Indications for intervention include dimensions > 4 cm, and associated symptoms, including spontaneous hemorrhage, pain and hematuria and the suspicion of malignancy[6]. De Luca et al[7] revealed that as the AML grows, the risk of compression symptoms and eventual hemorrhage from rupture increases due to hemorrhagic aneurysms. Transcatheter arterial embolization is one of the standard therapeutic options for AML. Compared to surgical treatment, arterial embolization may induce less surgical trauma and could spare more functioning renal tissue[8]. In addition, it was revealed that preoperative embolization could reduce tumor bulk[9] and avoid excess blood loss during surgery[10]. However, when confronted with a giant AML, delineating the boundary of AML can be difficult, as the circulation of a giant AML is more complex. The success of embolization relies to a great extent on the balance between to treat as much AML as possible while sparing as much normal renal parenchyma as possible[9]. Therefore, according to our accumulated experience and skills, we decided to perform a PN without preoperative embolization, and utilize a novel bleed-arresting strategy to reduce bleeding during the operation. The goals of management in AMLs are renal function preservation while ameliorating any symptoms and risks of hemorrhage[11]. Considering the large volume and deep location of the present mass, a robot-assisted LPN was planned to achieve complete removal of the tumor and adequate preservation of renal function. In terms of the surgical approaches for giant renal AMLs, the TP approach is more common as it provides a larger working space, better orientation and wider angles to reach tumors[10,12,13]. However, potential complications of the TP approach relate to the bowels caused by bowel mobilization which would prolong recovery time[3]. Direct access to the renal hilum as soon as possible to control the vascular pedicle was important in the present case. Considering that the mass occupied the hilum ventrally, a PN using the RP approach was carried out. Hughes-Hallett et al[14] revealed that the RP approach was associated with decreased operation time and fewer complications. With a well-planned strategy and the advantages of the robotic system, the shortcomings of the RP approach including small working space and poor kidney exposure were successfully overcome and the intention to preserve the right kidney as well as dissection of the ureter and renal vessels from the tumor were achieved. During the operation, the right kidney was thoroughly dissociated from perinephric fat and surrounding tissue via the dorsal and ventral space, respectively. This was the key step in the entire surgical procedure to overcome the shortcomings of the RP approach. The renal vessels (renal artery and vein) and ureter were also dissected as well as the renal pelvis. In particular, safe exposure of the renal veins was assured through adequate dissociation of the kidney. By implementing these measures, the risks of intraoperative renal hemorrhage and ureter injury were reduced and well-controlled. In addition, due to sufficient dissection of the renal vessels and ureter, the tumor margin was clearly identified and subsequent dissociation was smoothly performed. A previous study revealed that laparoscopic aspiration can be a safe and efficient technique for renal AMLs, especially for large and central renal AMLs[4]. This technique proved to be an effective method for exposing small vessels at the base to stop bleeding points and shorten the operation time. Therefore, when the bulk of the mass was resected from the kidney, aspiration was performed to eliminate remaining tumor tissue at the tumor base. Of course, it is necessary to expose the various basal areas of the tumor as much as possible in order to completely suck out the remaining tumor tissue. The soluble hemostatic gauze SurgicelTM is a novel hemostatic material which has been proved be quick and effective in achieving hemostasis during neurosurgery[15]. We innovatively applied this material in our patient in order to reduce blood loss and drain time. During the operation, several layers of hemostatic gauze were inserted into the wound fossa and totally compressed for a few minutes. The hemostatic gauze gradually resulted in clotting, and hemostasis was eventually achieved. The dosage of hemostatic gauzes depends on the size and depth of the wound fossa. Subsequent suturing was carried out when the hemorrhage was alleviated. For small wounds, suturing after tamponade is considered unnecessary. The postoperative hemoglobin level in our patient was within the normal range, demonstrating that the bleed-arresting strategy was effective. This innovative strategy for hemostasis could be a potential and more economical alternative for preoperative embolization of giant AML. To assess the differences between the two bleed-arresting strategies, a further well-designed prospective cohort study is required. Since there is no residual tumor tissue after careful aspiration around the base, there is no chance of tumor recurrence. We have not yet found a single case of recurrence from the original tumor site.

Robotic LPN via the RP approach was proved to be a safe and effective technique for giant central renal AMLs. Compared to the TP approach, it seemed to speed up the patient’s recovery and shorten the hospitalization time. A careful preoperative imaging evaluation plays an important role in the success of surgery. Complete dissociation of the kidney, the hilum vessels and ureter from perinephric fat as well as thorough exposure of the tumor were the key steps to successful surgery. In addition, the assistance of the robotic surgical system, the well-designed procedure and bleed-arresting strategy were also essential for a successful outcome.

| 1. | Murray TE, Lee MJ. Are We Overtreating Renal Angiomyolipoma: A Review of the Literature and Assessment of Contemporary Management and Follow-Up Strategies. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2018;41:525-536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Patel M, Porter J. Robotic retroperitoneal partial nephrectomy. World J Urol. 2013;31:1377-1382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Choo SH, Lee SY, Sung HH, Jeon HG, Jeong BC, Jeon SS, Lee HM, Choi HY, Seo SI. Transperitoneal versus retroperitoneal robotic partial nephrectomy: matched-pair comparisons by nephrometry scores. World J Urol. 2014;32:1523-1529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Xu B, Zhang Q, Jin J. Laparoscopic aspiration for central renal angiomyolipoma: a novel technique based on single-center initial experience. Urology. 2013;81:313-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chronopoulos PN, Kaisidis GN, Vaiopoulos CK, Perits DM, Varvarousis MN, Malioris AV, Pazarli E, Skandalos IK. Spontaneous rupture of a giant renal angiomyolipoma-Wunderlich's syndrome: Report of a case. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;19:140-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nelson CP, Sanda MG. Contemporary diagnosis and management of renal angiomyolipoma. J Urol. 2002;168:1315-1325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | De Luca S, Terrone C, Rossetti SR. Management of renal angiomyolipoma: a report of 53 cases. BJU Int. 1999;83:215-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lenton J, Kessel D, Watkinson AF. Embolization of renal angiomyolipoma: immediate complications and long-term outcomes. Clin Radiol. 2008;63:864-870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bishay VL, Crino PB, Wein AJ, Malkowicz SB, Trerotola SO, Soulen MC, Stavropoulos SW. Embolization of giant renal angiomyolipomas: technique and results. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010;21:67-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Shen WH, Pan JH, Yan JN, Chen ZW, Zhou ZS, Lu GS, Li WB. Resection of a giant renal angiomyolipoma in a solitary kidney with preoperative arterial embolization. Chin Med J (Engl). 2011;124:1435-1437. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Sivalingam S, Nakada SY. Contemporary minimally invasive treatment options for renal angiomyolipomas. Curr Urol Rep. 2013;14:147-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhou Y, Tang Y, Tang J, Deng F, Gan YU, Dai Y. Total nephrectomy with nephron-sparing surgery for a giant bilateral renal angiomyolipoma: A case report. Oncol Lett. 2015;10:2450-2452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cichocki M, Sosnowski M, Jablonowski Z. A giant renal angiomyolipoma (AML) in a patient with septo-optic dysplasia (SOD). Eur J Med Res. 2014;19:46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hughes-Hallett A, Patki P, Patel N, Barber NJ, Sullivan M, Thilagarajah R. Robot-assisted partial nephrectomy: a comparison of the transperitoneal and retroperitoneal approaches. J Endourol. 2013;27:869-874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Huo L, Ruan WH, Ding ZL, Cheng ZQ, Wu G. Clinical hemostasis effect of a novel hemostatic material SURGICELTM vs gelatin sponge in neurosurgery. Zhongguo Zuzhi Gongcheng Yanjiu Yu Linchuang Kangfu. 2012;16:551-554. |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Urology and nephrology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Sharma S, India; Tustumi F, Brazil S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ