Published online Apr 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i11.3573

Peer-review started: November 8, 2021

First decision: December 27, 2021

Revised: January 8, 2022

Accepted: February 27, 2022

Article in press: February 27, 2022

Published online: April 16, 2022

Processing time: 150 Days and 23.2 Hours

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic autoimmune disease characterized by relapsing-remitting abdominal pain, diarrhea, mucopurulent discharge and rectal bleeding. To date, the etiology of the disease remains unknown; therefore, medical therapy is not yet available. Left-sided UC is mainly treated with oral and topical mesalazine. However, due to its modest clinical effect, endoscopic mucosal remission is not achieved in all patients.

A 44-year-old man presented to Longhua Hospital with a history of left-sided UC for more than 6 years and slight bloody diarrhea over time. Endoscopy suggested hyperemia, edema, and erosive mucosa involving the rectum and sigmoid colon. The Traditional Chinese medicine Qingchang decoction (QCD) enema treatment was initiated once a day combined with a previous standard dose of mesalazine for 8 wk, and rectal bleeding ceased after 4 wk of treatment. Another QCD enema treatment was provided after symptom relapse due to drug withdrawal for nearly 6 mo. At the 2-mo follow-up, the colonoscopy results indicated mucosal healing with no erosion or ulcers.

The Chinese formula QCD retention enema represents a potential treatment for left-sided UC with predominant rectal bleeding to achieve clinical and mucosal remission.

Core Tip: We present a case of a 44-year-old man with mildly active left-sided ulcerative colitis (UC) for 6 years in whom mesalazine treatment failed but clinical and mucosal remission was achieved following Chinese formula Qingchang decoction (QCD) retention enema treatment combined with oral mesalazine. Thus, a QCD enema may be an effective treatment modality for patients with left-sided UC.

- Citation: Li PH, Tang Y, Wen HZ. Qingchang decoction retention enema may induce clinical and mucosal remission in left-sided ulcerative colitis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(11): 3573-3578

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i11/3573.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i11.3573

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic autoimmune disease characterized by relapsing-remitting abdominal pain, diarrhea, mucopurulent discharge, and rectal bleeding. Its lesions mainly involve the mucous membrane and submucosa of the colon. UC can be divided into proctitis, rectal-sigmoid colitis and extensive colitis[1], corresponding to 14.8%, 26.4% and 25.0% of all UC cases, respectively[2]. Left-sided colitis refers to colitis involving the lower part of the descending colon. The proportion of left-sided colitis in China exceeds 50%. The precise pathogenesis of UC remains unknown; therefore, medical therapy to cure the disease is not yet available. Therapeutic drugs include sulfasalazine, mesalazine, corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, and biological agents[3]. However, not all patients benefit from basic mesalazine and amino-salicylic acid treatment for left-sided UC. We report herein a case of a 44-year-old man with left-sided UC in whom standard oral and topical doses of mesalazine failed but clinical remission and mucosal healing were eventually achieved with the Chinese formula Qingchang decoction (QCD) enema. This publication reports and discusses the effects of QCD enema treatment on left-sided UC.

A 44-year-old Chinese man presented to Longhua Hospital with a history of left-sided UC for more than 6 years. He received oral treatment with mesalazine at a dose of 3 g/d (occasionally 2 g/d due to forgetting to take the medicine). Bowel movements were maintained 2-3 times a day, with a small amount of blood and mucus in the stool less than half of the time. Mesalazine suppository therapy and glucocorticoid enema were also administered briefly during this period, but the symptoms were not relieved. In the previous 6 years, colonoscopy was repeated annually, with results revealing a Mayo endoscopic score of 2 (erosion of the rectum and sigmoid colon covered with purulent secretions).

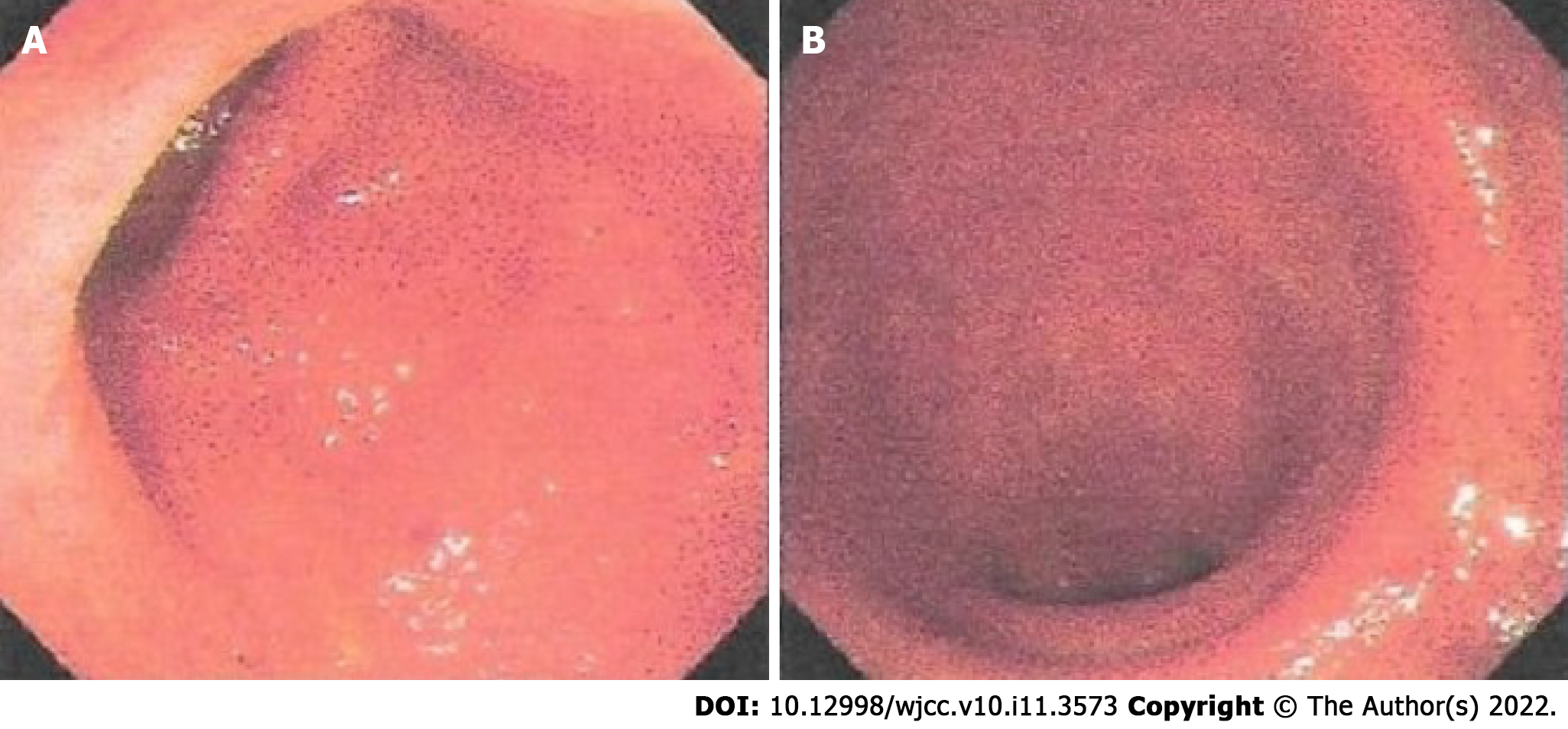

The patient suffered from recurrent bloody mucous stool. After another colonoscopy was conducted at a local hospital on October 30, 2019 (Figure 1), which suggested a diagnosis of active left-sided UC, he was admitted to our department on November 09, 2019. He reported bowel movements twice a day; mild, dull pain in the left lower abdomen that was relieved after a bowel movement; relapsing mucous discharge; and rectal bleeding when he was fatigued. We observed his tongue to be red with light yellow fur and a thin pulse.

The patient had no significant previous medical history.

The patient had no significant family history.

Physical examination showed no obvious abnormalities, except for slight tenderness in the left lower abdomen.

No sign of inflammation was found in the blood analysis, and the leukocyte level was low, at 3.55 × 109/L, with predominant neutrophils (67.1%) and normal hemoglobin and platelet counts. The prothrombin level, partial thromboplastin times, and d-dimer levels were normal. The serum C-reactive protein level was also within normal limits, and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 2 mm/h. The blood biochemistry and urine analyses were normal. The ECG results were also normal.

The patient was diagnosed with UC subtyped as left-sided colitis based on endoscopy of the rectum and colon (Figure 1) and histology of the biopsy. His condition was mild in severity with an active persistent phase. The relevant Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) syndrome was spleen deficiency and the accumulation of dampness and heat.

Treatment with QCD enema was administered to the patient at a dose of 180 mL once a night, combined with oral mesalazine at a dose of 3 g/d. Rectal bleeding ceased after 4 wk of treatment, and after 8 wk of treatment, the patient had one or two bowel movements per day, and no mucous or bloody discharge was observed. Due to the satisfactory effect, the dose of oral mesalazine was reduced to 2 g/d, and enema therapy was stopped without a consultation. At the end of June 2020, relapsing mucous and bloody discharge 3 to 4 times a day occurred. On June 22, 2020, the patient came to our ward for further treatment with QCD enema. The stool frequency was reduced to 2 to 3 times a day, with no mucus or blood present after 4 wk of treatment.

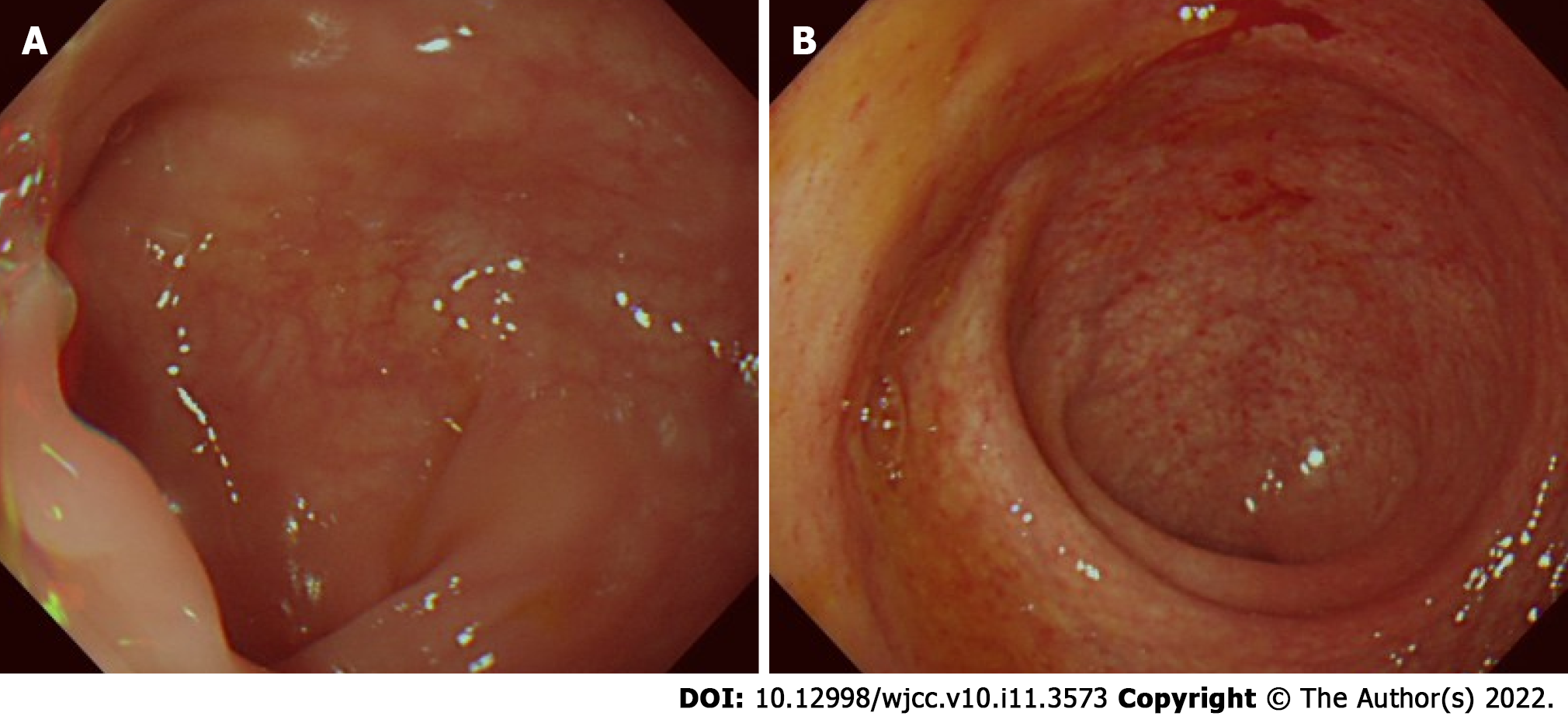

The patient received a total of 12 wk of QCD retention enema treatment combined with oral mesalazine. After the second episode of QCD treatment, on August 07, 2020, a colonoscopy was performed again. Normal mucosa was seen in the sigmoid colon (Figure 2A), and relative healing with patchy hyperemia was detected in the rectum (Figure 2B). The endoscopic Mayo score was evaluated as 1, which indicated that the integrated treatment induced both clinical and endoscopic remission. Subsequently, oral mesalazine was continued at a dose of 2 g/d with a QCD retention enema twice a week. The patient was last followed up on September 28, 2021, and he had no abdominal pain, nor bloody stool with mucus.

As a subtype of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), UC is characterized by chronic inflammation of the colonic mucosa and recurrent attack. The exact etiology and pathogenesis of UC remain unclear, and treatment options are limited. For long-standing UC, typically 8 or 10 years after disease onset, there is a defined risk of dysplasia and colorectal cancer caused by persistent large-scale colonic inflammation[4]. A targeted therapy that focuses on endoscopic mucosal healing rather than mere symptom remission has emerged as a new preferred concept in the management approach of IBD[5]. Mucosal healing refers to the resolution of inflammatory changes (Mayo endoscopic subscore of 0 or 1)[5]. It is essential to manage UC in the remission phase with the minimum category or dose of medicine due to the limited choice of medications.

The guidelines recommend oral mesalazine at a dose of ≥ 2.4 g/d combined with an amino-salicylic acid preparation enema ≥ 1 g/d as a first-line treatment for mild to moderate left-sided UC[3]. The guidelines also indicate that the local effect of mesalazine is better than that of topical corticosteroids. However, not all patients benefit from this treatment. For instance, the study by Marteau et al[6] showed that the remission rate of UC treated with mesalazine at a dose of 4 g/d combined with 1 g/d enema was 64%. A randomized controlled trial (RCT) by Hartmann et al[7] used mesalazine or budesonide enema therapy for patients with mild to moderate left-sided UC. The proportion of these patients in whom endoscopic remission (defined as an endoscopic score < 2) was achieved was 71.7% (76/106) and 68.0% (76/103), respectively. Bokemeyer et al[8] reported that 78.8%-84.4% of left-sided UC patients were assigned an endoscopic score of 0 or 1 (0 = normal or inactive disease; 1= mild disease, erythema, decreased vascular pattern, and mild friability) after 12 mo of oral mesalazine at a dose of 2 g/d. In conclusion, oral mesalazine and/or enema therapy is ineffective for approximately 20% to 30% of patients with left-sided UC. The guidelines[5] recommend using systemic corticosteroid therapy, but a large portion of patients in practice are unwilling to receive oral or intravenous corticosteroid therapy due to their side effects. For patients with poor outcomes with mesalazine treatment and who are unwilling to accept systemic corticosteroid treatment, TCM therapy is an effective option, which is also documented in China’s IBD guidelines[1].

Although UC has no corresponding disease name in TCM, it has long been recorded throughout history and is well understood. According to the description of the clinical manifestations of “changpi”, “Xiali”, “chronic dysentery”, and “recurrent dysentery” in the medical documents of the previous dynasties, it is not difficult to connect these diseases with UC. According to TCM theory, UC is located in the large intestine, and the main pathogenesis lies in dampness and heat accumulation. The stagnation of qi and blood with dampness and heat thus leads to the formation of pus. Heat toxicity also burns intestinal collaterals, causing blood perfusion outside of the collaterals. These pathological processes induce symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, and mucopurulent bloody stools. In the mid-1980s, Gui-Tong Ma, a renowned doctor at Longhua Hospital, developed the Qingchang suppository (QCS), which was the first suppository for rectal administration composed of pure Chinese herbs in China. QCS exerts its effect of clearing heat and dampness, promoting blood circulation and removing blood stasis by targeting four major pathogenic factors, namely, dampness, heat, toxicity, and blood stasis.

The QCS (Z05170722) consists of Indigo naturalis (IN), Radix notoginseng, Gallnut, Herba portulacae and Borneol[9]. As the most essential component of QCS, IN is a commonly used Chinese herb to cure UC by reducing inflammation and rectal bleeding. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial conducted by Japanese researchers demonstrated that 8 wk of IN administration (0.5-2.0 g per day) induced a clinical response and mucosal healing in patients with active UC[10]. IN includes indigo and indirubin molecules[11], which act as representative human aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) ligands. AHR signaling stimulates the production of interleukin-22 in mucosal type 3 innate lymphocytes, thus inducing the production of tight junction molecules and antimicrobial peptides, which contribute to mucosal healing[12]. IN also has an anti-inflammatory role by downregulating proinflammatory factors such as IL-1α, IL-6, IL-1β, IL-8 and TNF-α[13].

The mechanism of QCS has also been fully investigated. Sun et al[9] used QCS and sulfasalazine suppository (SASP) to treat rats with dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis and normal control rats. The levels of the proinflammatory factors TNF-α and IL-6 were suppressed with both treatments, suggesting that QCS has anti-inflammatory effects. Moreover, the production of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α, and inducible NO synthase (iNOS) was also inhibited in the QCS- and SASP-treated groups, suggesting that QCS can restrain colonic vascular permeability and promote epithelial integrity and colonic hypoxia. Lu et al[14] administered low, medium, and high doses of QCS and SASP to rats with trinitro-benzene-sulfonic acid (TNBS)-induced colitis and observed the expression of F-actin protein, which is a major component of the cytoskeleton, through immunofluorescence. The study revealed that QCS can improve F-actin protein content based on reduction after modeling, which suggested that it can reduce the damage of UC to the mucosal cytoskeleton and protect the integrity of the intestinal barrier. These studies support the notion that QCS can effectively alleviate colonic inflammation in UC.

The clinical effect of QCS has been fully investigated. However, clinical trials aiming to identify the effect of QCD enema have not yet been conducted. A previous multicenter RCT demonstrated that an efficacy rate of 91.49% 8 wks after the initiation of QCS treatment at a dose of 2 g/d was achieved in patients with mild to moderate proctitis compared with 87.23% in the SASP treatment group (P > 0.05)[15]. Complete efficacy was defined as the basic disappearance of clinical symptoms and mild mucosal inflammation or the formation of pseudopolyps found by colonoscopy. The outcome of this study also demonstrated that QCS has more advantages in relieving symptoms such as abdominal pain and distention, tenesmus, mucopurulent stool, and burning anal pain. After a one-year follow-up of the QCS group (9.3%), the recurrence rate was significantly lower than that of the SASP group (26.83%). These results indicated that QCS is effective in inducing and maintaining clinical and mucosal remission.

Considering that the suppository application location is mainly limited to the rectum while an enema can reach the descending colon, a QCD enema was thus developed according to the components of QCS for the treatment of left-sided UC. In the case reported here, the patient with active left-sided UC suffered for 6 years after standard oral therapy with mesalazine and intermittent topical treatment. Based on oral mesalazine maintenance treatment, an additional QCD enema at a dose of 180 mL/d successfully induced endoscopic mucosal healing. Although this is a case report, it provides preliminary evidence for the treatment of active left-sided UC. In the future, we will continue to follow up with this patient and collect more cases of QCD treatment for UC to provide more evidence for its treatment effect in left-sided UC.

The case described herein demonstrates that the Chinese formula QCD retention enema can effectively reduce both the clinical and mucosal remission of left-sided UC, thus providing another effective therapy other than mesalazine. This finding provides a new understanding of the treatment of left-sided UC and a basis for further studies to determine the underlying mechanism of the QCD treatment effects.

| 1. | Inflammatory Bowel Disease Group; Chinese Society of Gastroenterology (CSG), Chinese Medical Association. A consensus view on the diagnosis and treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Zhonghua Xiaohua Zazhi. 2018;38:292-311. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | Chinese inflammatory bowel disease cooperative group. Retrospective analysis of 3100 hospitalized cases of ulcerative colitis. Zhonghua Xiaohua Zazhi. 2006;26:368-372. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Harbord M, Eliakim R, Bettenworth D, Karmiris K, Katsanos K, Kopylov U, Kucharzik T, Molnár T, Raine T, Sebastian S, de Sousa HT, Dignass A, Carbonnel F; European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation [ECCO]. Third European Evidence-based Consensus on Diagnosis and Management of Ulcerative Colitis. Part 2: Current Management. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:769-784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1016] [Cited by in RCA: 911] [Article Influence: 101.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Yashiro M. Ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16389-16397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rubin DT, Ananthakrishnan AN, Siegel CA, Sauer BG, Long MD. ACG Clinical Guideline: Ulcerative Colitis in Adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:384-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 870] [Cited by in RCA: 1140] [Article Influence: 162.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Marteau P, Probert CS, Lindgren S, Gassul M, Tan TG, Dignass A, Befrits R, Midhagen G, Rademaker J, Foldager M. Combined oral and enema treatment with Pentasa (mesalazine) is superior to oral therapy alone in patients with extensive mild/moderate active ulcerative colitis: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled study. Gut. 2005;54:960-965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 247] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hartmann F, Stein J; BudMesa-Study Group. Clinical trial: controlled, open, randomized multicentre study comparing the effects of treatment on quality of life, safety and efficacy of budesonide or mesalazine enemas in active left-sided ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:368-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bokemeyer B, Hommes D, Gill I, Broberg P, Dignass A. Mesalazine in left-sided ulcerative colitis: efficacy analyses from the PODIUM trial on maintenance of remission and mucosal healing. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:476-482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sun B, Yuan J, Wang S, Lin J, Zhang W, Shao J, Wang R, Shi B, Hu H. Qingchang Suppository Ameliorates Colonic Vascular Permeability in Dextran-Sulfate-Sodium-Induced Colitis. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Naganuma M, Sugimoto S, Mitsuyama K, Kobayashi T, Yoshimura N, Ohi H, Tanaka S, Andoh A, Ohmiya N, Saigusa K, Yamamoto T, Morohoshi Y, Ichikawa H, Matsuoka K, Hisamatsu T, Watanabe K, Mizuno S, Suda W, Hattori M, Fukuda S, Hirayama A, Abe T, Watanabe M, Hibi T, Suzuki Y, Kanai T; INDIGO Study Group. Efficacy of Indigo Naturalis in a Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial of Patients With Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:935-947. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Plitzko I, Mohn T, Sedlacek N, Hamburger M. Composition of Indigo naturalis. Planta Med. 2009;75:860-863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sugimoto S, Naganuma M, Kanai T. Indole compounds may be promising medicines for ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:853-861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wang Y, Liu L, Guo Y, Mao T, Shi R, Li J. Effects of indigo naturalis on colonic mucosal injuries and inflammation in rats with dextran sodium sulphate-induced ulcerative colitis. Exp Ther Med. 2017;14:1327-1336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lu L, Xie JQ, Yuan JY, Qiu SK. Effect of Qingchang Suppository on fibroactin of colonic mucosa in rats with ulcerative colitis. Zhongguo Zhongxiyi Jiehe Xiaohua Zazhi. 2012;20:485-488. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Gong YP, Liu W, Ma GT, Hu HY, Xie JQ, Tang ZP, Hao WW, Bian H, Zhu LY, Wu HP, Randomized controlled study of Qingchang Suppository in the treatment of ulcerative colitis. Shanghai Zhongyiyao Daxue Xuebao. 2007;33-36. [DOI] [Full Text] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cheng TH, Taiwan; Salimi M, Iran S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Chen YL