Published online Jan 7, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i1.388

Peer-review started: September 7, 2021

First decision: September 29, 2021

Revised: October 23, 2021

Accepted: November 22, 2021

Article in press: November 22, 2021

Published online: January 7, 2022

Processing time: 114 Days and 3.5 Hours

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage at C1/2 in spontaneous intracranial hypo

A 60-year-old man with no history of trauma was admitted to our hospital with orthostatic headache, nausea, and vomiting. Brain computed tomography imaging revealed bilateral, subacute to chronic SDH. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings were SDH with dural enhancement in the bilateral cerebral convexity and posterior fossa and mild sagging, suggesting SIH. Although the patient underwent burr hole trephination, the patient’s orthostatic headache was aggravated. MR myelography led to a suspicion of CSF leakage at C1/2. Therefore, we performed a targeted cervical EBP using an epidural catheter under fluoroscopic guidance. At 5 d after EBP, a follow-up MR myelography revealed a decrease in the interval size of the CSF collected. Although his symptoms improved, the patient still complained of headaches; therefore, we repeated the targeted cervical EBP 6 d after the initial EBP. Subsequently, his headache had almost disappeared on the 8th day after the repeated EBP.

Targeted EBP is an effective treatment for SDH in patients with SIH due to CSF leakage at C1/2.

Core Tip: Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage at C1/2 in spontaneous intracranial hypotension (SIH) is rare. Subdural hematoma (SDH), a serious complication of SIH, may lead to neurological deficits. After a repeated targeted cervical epidural blood patch using an epidural catheter under fluoroscopic guidance, the patient’s symptoms had almost disappeared, and a magnetic resonance myelography revealed a decrease in the interval size of the CSF collected. This case highlights the efficacy of the delivery of autologous blood via an epidural catheter inserted into the lower cervical spine as a treatment for SDH in patients with SIH due to CSF leakage at C1/2.

- Citation: Choi SH, Lee YY, Kim WJ. Epidural blood patch for spontaneous intracranial hypotension with subdural hematoma: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(1): 388-396

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i1/388.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i1.388

Spontaneous intracranial hypotension (SIH) is a clinical syndrome of low cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure (less than 60 mmH2O) resulting from spontaneous CSF leakage in patients without any previous history of dural puncture or trauma. Commonly underdiagnosed, SIH has an estimated incidence of 5 per 100000 people in the general population[1-3]. SIH is predominant in women, and the mean age of occurrence is 40 to 45 years in both genders[4-6]. CSF leakage has been most commonly reported in the cervicothoracic junction and thoracic area at a single site or at multiple sites[5]. The classic presentation of SIH is an abrupt-onset, daily, persistent, orthostatic headache that improves in the supine position. Additionally, it is characterized by neck pain, nausea, vomiting, and dizziness. Occasionally, other neurological symptoms may also be present, including tinnitus, muffled hearing, photophobia, phonophobia, nerve palsies, dementia, peripheral neuropathy, and seizures[7,8]. Neuroradiological imaging facilitates the diagnosis of SIH and helps avoid invasive procedures[9]. Magnetic resonance (MR) myelography is an important diagnostic tool for detecting the leakage site of CSF[10].

SIH generally resolves spontaneously and is often treated conservatively with hydration, bed rest, caffeine, and an abdominal binder. If the condition fails to resolve, an autologous epidural blood patch (EBP) is considered the treatment of choice for patients who have failed initial conservative treatments. For SIH with CSF leakage in the high cervical region, EBP has traditionally been performed in the lumbar area or the thoracic and lower cervical areas[11], because a direct EBP at the leakage site may present challenges due to the narrow space in the region and its proximity to important neural structures[12]. However, a targeted EBP was shown to have higher success rates[13].

Subdural hematoma (SDH), a serious complication of SIH, can cause neurological deficits[14]. SDH and subdural hygromas are common radiographic manifestations of SIH, occurring in 50% of the patients[15]. However, the etiology of SDH in SIH patients remains unclear[15], and the optimal management of SDH associated with SIH is still undetermined. Whether EBP or surgery should be performed as the initial procedure remains controversial; EBP should be performed prior to irrigation of the hematoma. However, in some cases where SDH becomes symptomatic or the hematoma volume increases, irrigation of the hematoma should be considered[16].

We report the case of an SDH patient with CSF leakage at the C1/2 spinal level, who was successfully treated with a targeted cervical EBP using an epidural catheter under fluoroscopic guidance after surgical intervention.

A 60-year-old man (160 cm, 70 kg) presented to our Neurosurgery Department with a one-month history of progressively worsening parietal headache, posterior neck pain, nausea, vomiting, and vertigo.

The headache worsened when sitting or standing and partially regressed when lying down. Initially, the symptoms lasted for one hour but gradually worsened and began to last the entire day. The pain intensity of the headache measured on a Numeral Rating Scale (NRS) was aggravated from 4 to 8 throughout the month prior to presentation. During the month when his symptoms developed, the pain became increasingly global, with worsening orthostatic headache, nausea, and vomiting.

He had a free previous medical history and no trauma history.

He had no relevant family history.

He showed no neurologic signs.

The results of routine blood and urine tests, blood biochemistry, and immune and infection indexes were normal.

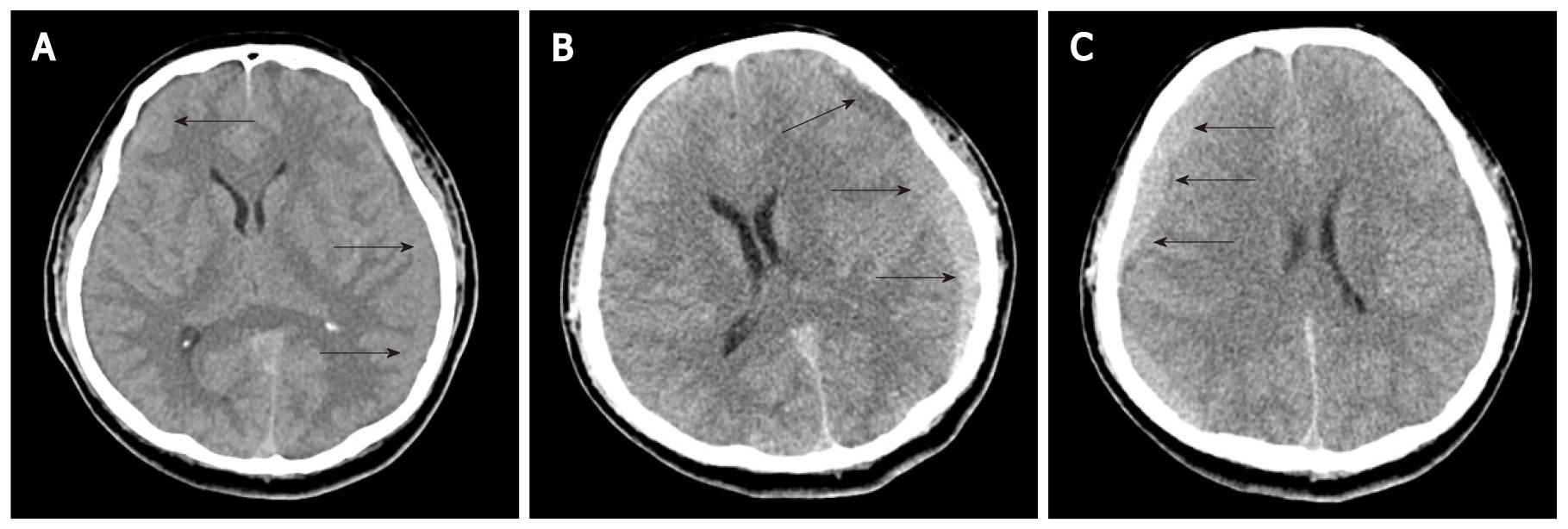

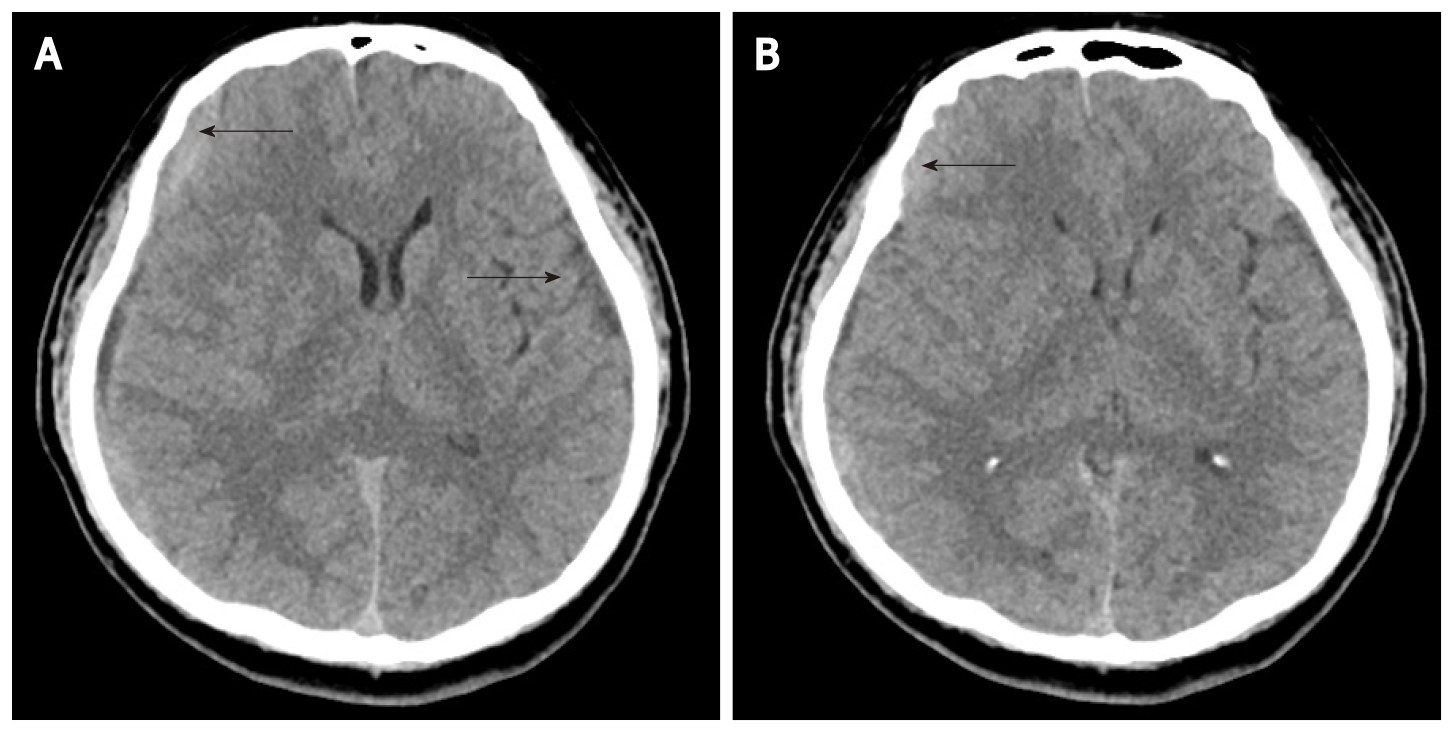

Brain computed tomography (CT) imaging revealed probable subacute to chronic stage of SDH along the bilateral frontoparietotemporal cerebral convexities (Figure 1A).

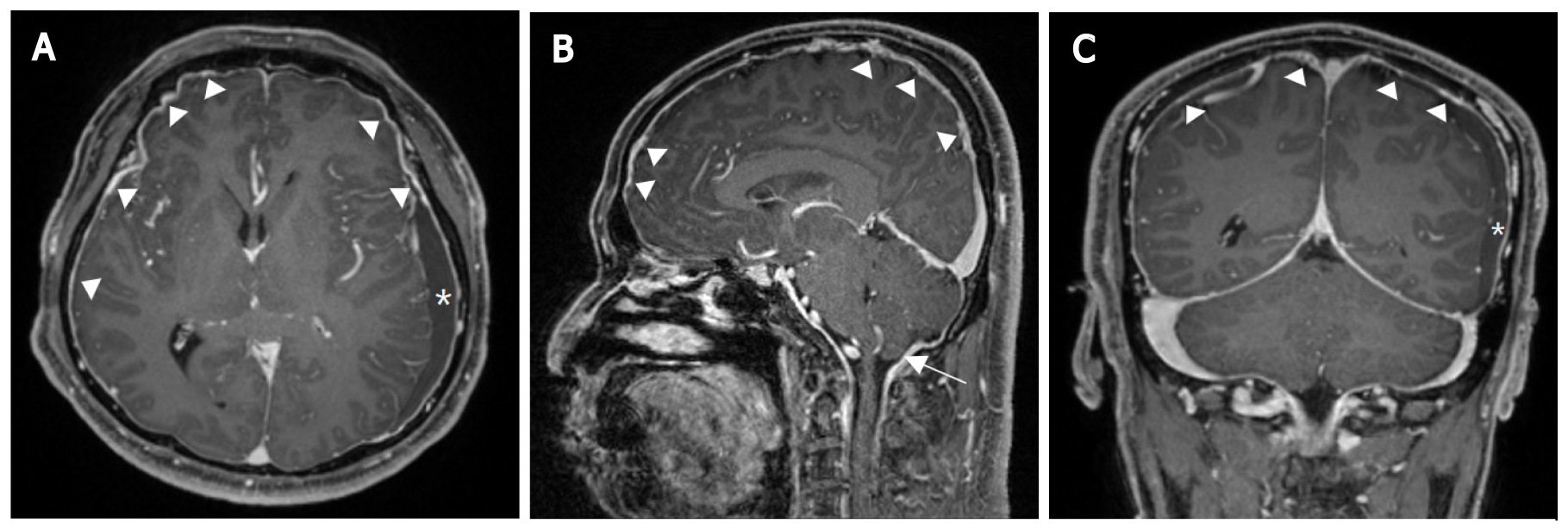

The patient was initially treated with conservative management, including bed rest, intravenous fluid administration, and analgesics. However, the headache and associated symptoms did not improve. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a large amount of multistage SDH with recent bleeding in the left cerebral convexity, a mild subfalcine herniation to the right, dural enhancement in both cerebral convexity and posterior fossa, and a mild sagging appearance of the brain (Figure 2).

SIH was suspected based on these findings.

Follow-up CT findings included the increased attenuation of SDH along the left frontoparietotemporal cerebral convexities with mild midline shifting (Figure 1B). Accordingly, the patient underwent a burr hole trephination at hospital day (HD) 7.

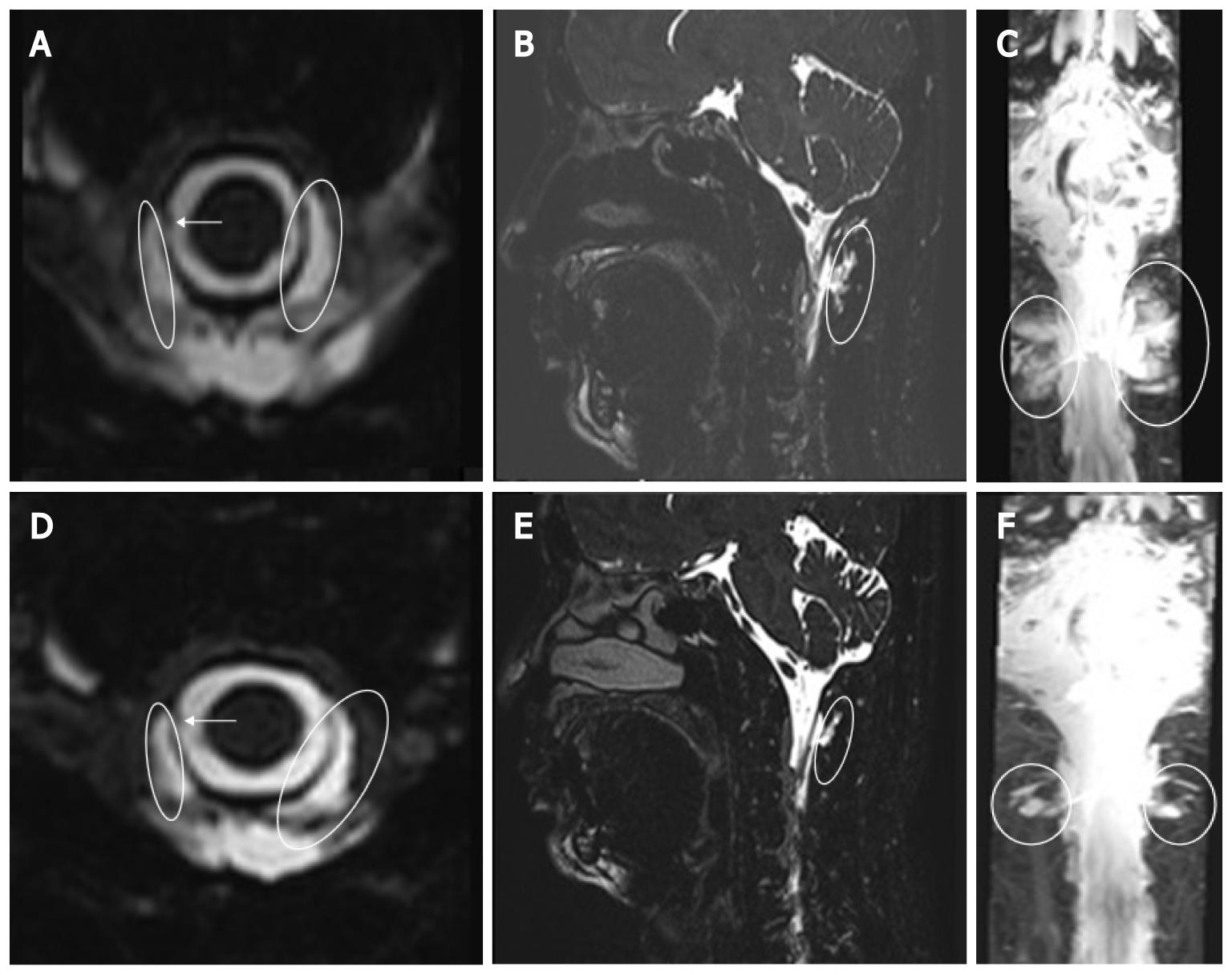

However, the patient’s orthostatic headache was aggravated, and follow-up CT findings included a slightly re-increased amount of SDH along the right frontoparietotemporal cerebral convexities (Figure 1C). MR myelography of the entire spinal column was performed, leading to the suspicion of CSF leakage at C1/2 with a suspicious focal dural sac defect at the C1/2 level on the right side and fluid collection in the bilateral and posterior C1/2 epidural space (Figure 3A-C). Therefore, the patient consulted our pain clinic for EBP.

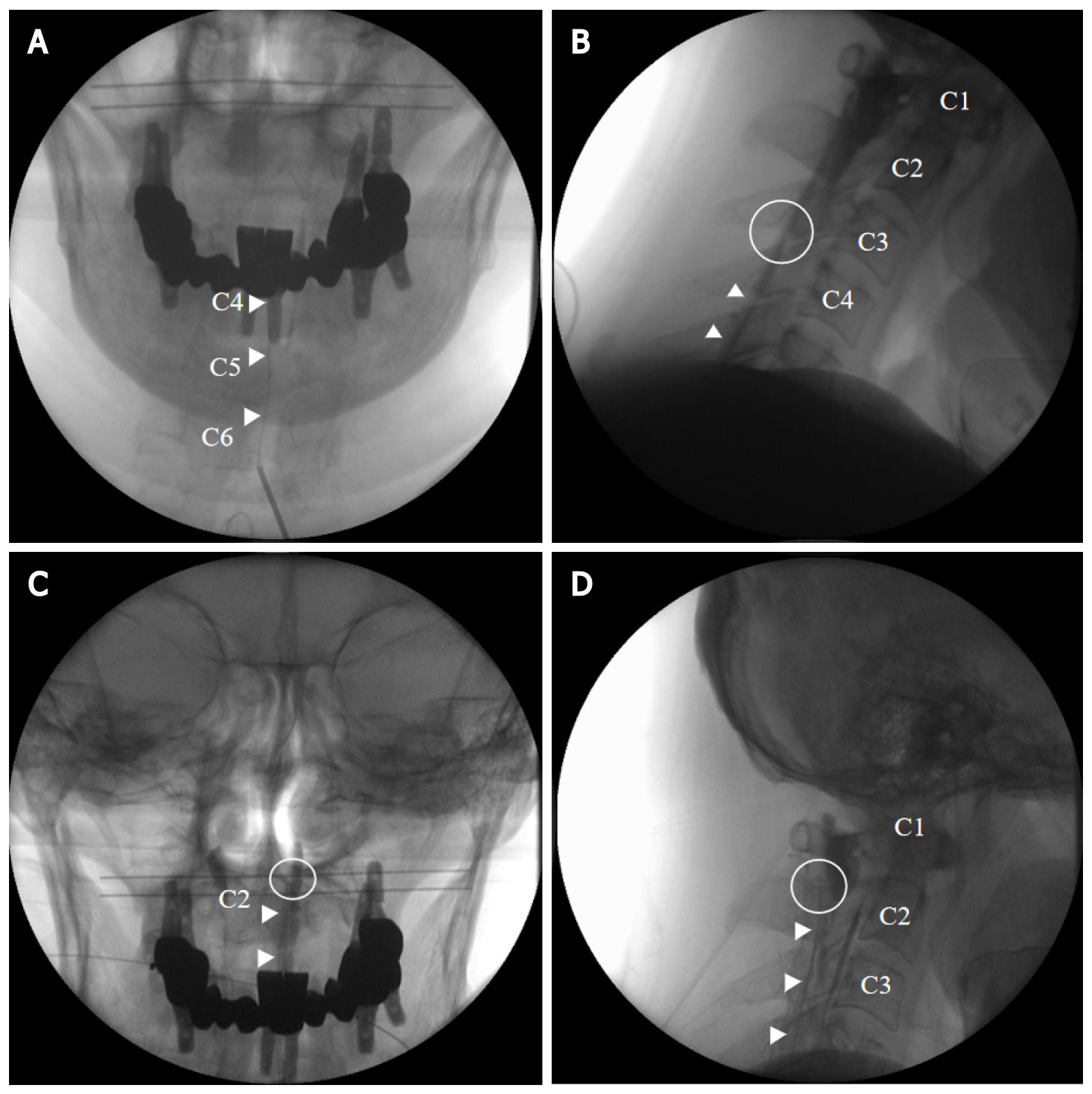

We performed a targeted cervical EBP using an epidural catheter under fluoroscopic guidance at HD 17. The patient was placed in a prone position with a pillow under the chest. The skin was infiltrated with lidocaine. An 18 G epidural needle was slowly inserted at the C6/7 interlaminar space using a right paramedian approach under fluoroscopic guidance. The needle was advanced into the epidural space using a loss-of-resistance technique. The epidural space was confirmed with visualization of the contrast agent using anteroposterior and lateral fluoroscopic views. The epidural catheter was passed through the needle and directed in the cephalad direction to the C3/4 level in the right paramedian. However, we were unable to advance the catheter further in the cephalad direction, despite multiple attempts. We injected 1 mL of the contrast medium and confirmed the spread of the contrast dye at the C1/2 level (Figure 4A and B). Then, 5 mL of autologous blood was injected via the epidural catheter.

At 5 d after EBP, a follow-up MR myelography revealed a decreased interval size of CSF collected at C1/2 (from 15 mm × 7 mm to 13 mm × 4 mm) with focal right-side dural sac thinning (Figure 3D-F). Although the symptoms improved, we decided to repeat the EBP 6 d after the initial EBP as the patient still complained of headaches. The EBP was performed in the same way as the previous procedure; however, this time, the catheter tip approached the correct C1/2 level (Figure 4C and D). We injected 1 mL of the contrast medium to confirm the spread of the contrast dye at the correct C1/2 level followed by 5 mL of autologous blood into the epidural space through the cervical epidural catheter. No paresthesia was encountered during the injection of blood, and the catheter was removed at the end of the procedure. The patient’s headache and associated symptoms gradually improved. Follow-up CT findings included reduced attenuation of SDH along the left frontoparietotemporal cerebral convexities and reduced amount of SDH along the right frontoparietotemporal cerebral convexities (Figure 5). As the headache almost disappeared on the 8th day after the repeated EBP, the patient was discharged.

The primary goal of SIH treatment is to stop the CSF leakage and increase the CSF volume[17]. Traditionally, treatment for SIH begins with conservative therapy including hydration, analgesics, and abdominal binders[1]. Autologous EBP is considered the treatment of choice for patients who have failed initial conservative treatments. The exact mechanism of autologous EBP is still not precisely defined. It is hypothesized that blood clots, once injected, could stop dural leakage and promote rapid healing of punctures. In addition, given that most patients experience immediate pain relief, it is hypothesized that EBP increases intracranial CSF pressure and volume through an epidural mass effect[18]. An increase in CSF volume helps to reverse the mechanical traction applied to the pain-sensitive area, as well as to reverse the transient central venous dilatation that contributes to pain[19].

One of the therapeutic mechanisms of the blood patch involves covering the meningeal tear site with a blood clot[5]. Therefore, autologous EBP procedures are performed as close to the leakage site as possible to increase their success rate[20]. Targeted EBP is an autologous blood injection that identifies and targets the source of a CSF leak. On the other hand, blind EBP is an autologous blood injection, usually into the lumbar spine, without prior identification of the source of the leak[13]. Although there is no consensus on the benefits of targeted EBP compared to blind EBP in SIH, targeted EBP has a higher rate of success than blind EBP[13]. In a study comparing the efficacy of targeted EBP to that of blind EBP, 87.1% of the patients, who received targeted EBP, showed marked clinical improvement after only one EBP procedure, whereas 52% of the patients, who received blind lumbar or upper thoracic EBP, showed improvement after one EBP procedure[12]. In addition, 21% of the patients, who were treated with targeted EBP, underwent repeated EBP procedures while 61% of the patients, who were treated with blind EBP, had to get repeated EBP procedures[13].

Various complications can occur after autologous EBP. The most common complication is mild, self-limiting pain near the injection site, often related to the amount of blood injected[21]. EBP is also associated with rare complications of meningitis, epidural or intradural hematomas, pneumocephalus, arachnoiditis, epidural or subdural abscesses, facial nerve palsy, and cauda equina syndrome[22]. Targeted EBP may be associated with an increased risk of complications including spinal cord and nerve root compression, dural puncture, chemical meningitis, neck stiffness, and seizures[12]. Moreover, EBP in the upper cervical spine is technically difficult because of anatomical complexities and poses a greater risk of complications than lumbar EBP[23]. In our case, because the patient’s orthostatic headache was aggravated despite the surgical intervention, we planned to perform targeted EBP immediately.

In the present case, the EBP was delivered at the C1/2 level via a cervical epidural catheter inserted at the C6/7 level and advanced into the cephalad under fluoroscopic guidance. There have been some reports of targeted EBP using an epidural catheter in SIH due to C1/2 leakage[24-26]. Our report differs from previous reports in the following ways. First, we showed the C-arm image of the location of the epidural catheter tip and the spread of the contrast agent in detail. Second, we confirmed that the amount of CSF leakage was reduced by performing follow-up MR myelography after EBP. Thus, targeted EBP was implemented successfully in an SIH patient with SDH.

Remarkable technological improvements have led to imaging techniques becoming significant diagnostic tools for SIH. MR myelography is the most common non-invasive technique for detecting CSF leak sites, which may reveal pachymeningeal enhancement, epidural fluid outflow extending into the soft tissues surrounding the spinal cord, and engorgement of the epidural venous plexus[27]. Enhanced MRI may also show subdural fluid collection, diffuse pachymeningeal enhancement, obliteration of basal cisterns, descending of the cerebellar tonsils, congested cerebral venous sinuses, enlarged pituitary gland, and decreased ventricular size[1].

Although the pathophysiology of SDH in patients with SIH remains unknown, studies have proposed several mechanisms. Downward displacement of the brain due to low CSF pressure may produce tears in the bridging veins of the dural border cell layer, causing their rupture. Alternatively, as subdural CSF collections gradually enlarge the subdural space, the bridging veins may stretch and rupture in some cases[17].

The optimal management of SDH associated with SIH remains to be determined. Chen et al[28] demonstrated that SIH patients with SDH maximal thickness < 10 mm had good outcomes without the need for surgical intervention, and the risk of neurological deterioration increased dramatically in patients with acute SDH maximal thickness ≥ 10 mm. Surgical intervention for critically symptomatic SDH was not detrimental to patients with SIH but was necessary to relieve a life-threatening increase in intracranial pressure and avoid uncal herniation. Cases of large SDH require surgical drainage and treatment of the underlying cause of SIH[29]. De Noronha et al[30] reported four consecutive SIH patients with acute deterioration of consciousness related to enlarged subdural collections, who had favorable outcomes after surgical drainage[30]. Some authors noted that subdural fluid collection could be managed safely by directing treatment to the underlying CSF leakage without hematoma evacuation[15]. In contrast, other authors reported the ineffectiveness of surgery or even postoperative acute neurological worsening or brain herniation[15,31-33].

Targeted EBP via a cervical epidural catheter inserted from the lower cervical spine under fluoroscopic guidance was an effective method of treatment for SDH in a patient with SIH due to CSF leakage at the C1/2 level.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: Johan MP, Osawa I, Teragawa H S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Fan JR

| 1. | Mokri B. Spontaneous intracranial hypotension. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2001;5:284-291. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Schievink WI, Maya MM, Moser F, Tourje J, Torbati S. Frequency of spontaneous intracranial hypotension in the emergency department. J Headache Pain. 2007;8:325-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kim YA, Yoon DM, Yoon KB. Epidural Blood Patch for the Treatment of Abducens Nerve Palsy due to Spontaneous Intracranial Hypotension -A Case Report-. Korean J Pain. 2012;25:112-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Diaz JH. Epidemiology and outcome of postural headache management in spontaneous intracranial hypotension. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2001;26:582-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Inamasu J, Guiot BH. Intracranial hypotension with spinal pathology. Spine J. 2006;6:591-599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mea E, Chiapparini L, Savoiardo M, Franzini A, Bussone G, Leone M. Headache attributed to spontaneous intracranial hypotension. Neurol Sci. 2008;29 Suppl 1:S164-S165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Apte RS, Bartek W, Mello A, Haq A. Spontaneous intracranial hypotension. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;127:482-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Peng PW, Farb R. Spontaneous C1-2 CSF leak treated with high cervical epidural blood patch. Can J Neurol Sci. 2008;35:102-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Allegri M, Lombardi F, Custodi VM, Scagnelli P, Corona M, Minella CE, Braschi A, Arienta C. Spontaneous cervical (C1-C2) cerebrospinal fluid leakage repaired with computed tomography-guided cervical epidural blood patch. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40:e9-e12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Matsumura A, Anno I, Kimura H, Ishikawa E, Nose T. Diagnosis of spontaneous intracranial hypotension by using magnetic resonance myelography. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2000;92:873-876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kim BW, Jung YJ, Kim MS, Choi BY. Chronic subdural hematoma after spontaneous intracranial hypotension : a case treated with epidural blood patch on c1-2. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2011;50:274-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cho KI, Moon HS, Jeon HJ, Park K, Kong DS. Spontaneous intracranial hypotension: efficacy of radiologic targeting vs blind blood patch. Neurology. 2011;76:1139-1144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rettenmaier LA, Park BJ, Holland MT, Hamade YJ, Garg S, Rastogi R, Reddy CG. Value of Targeted Epidural Blood Patch and Management of Subdural Hematoma in Spontaneous Intracranial Hypotension: Case Report and Review of the Literature. World Neurosurg. 2017;97:27-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Loya JJ, Mindea SA, Yu H, Venkatasubramanian C, Chang SD, Burns TC. Intracranial hypotension producing reversible coma: a systematic review, including three new cases. J Neurosurg. 2012;117:615-628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Schievink WI, Maya MM, Moser FG, Tourje J. Spectrum of subdural fluid collections in spontaneous intracranial hypotension. J Neurosurg. 2005;103:608-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Takahashi K, Mima T, Akiba Y. Chronic Subdural Hematoma Associated with Spontaneous Intracranial Hypotension: Therapeutic Strategies and Outcomes of 55 Cases. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2016;56:69-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Schievink WI. Spontaneous spinal cerebrospinal fluid leaks and intracranial hypotension. JAMA. 2006;295:2286-2296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 667] [Cited by in RCA: 725] [Article Influence: 36.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kroin JS, Nagalla SK, Buvanendran A, McCarthy RJ, Tuman KJ, Ivankovich AD. The mechanisms of intracranial pressure modulation by epidural blood and other injectates in a postdural puncture rat model. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:423-429, table of contents. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Gaiser RR. Postdural Puncture Headache: An Evidence-Based Approach. Anesthesiol Clin. 2017;35:157-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Feigl GC, Schebesch KM, Rochon J, Warnat J, Woertgen C, Schmidt S, Lange M, Schlaier J, Brawanski AT. Analysis of risk factors influencing the development of severe dizziness in patients with vestibular schwannomas in the immediate postoperative phase. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2011;113:52-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Booth JL, Pan PH, Thomas JA, Harris LC, D'Angelo R. A retrospective review of an epidural blood patch database: the incidence of epidural blood patch associated with obstetric neuraxial anesthetic techniques and the effect of blood volume on efficacy. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2017;29:10-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Patel R, Urits I, Orhurhu V, Orhurhu MS, Peck J, Ohuabunwa E, Sikorski A, Mehrabani A, Manchikanti L, Kaye AD, Kaye RJ, Helmstetter JA, Viswanath O. A Comprehensive Update on the Treatment and Management of Postdural Puncture Headache. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2020;24:24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Buvanendran A, Byrne RW, Kari M, Kroin JS. Occult cervical (C1-2) dural tear causing bilateral recurrent subdural hematomas and repaired with cervical epidural blood patch. J Neurosurg Spine. 2008;9:483-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wang E, Wang D. Successful treatment of spontaneous intracranial hypotension due to prominent cervical cerebrospinal fluid leak with cervical epidural blood patch. Pain Med. 2015;16:1013-1018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kwon SY, Kim YS, Han SM. Spontaneous C1-2 cerebrospinal fluid leak treated with a targeted cervical epidural blood patch using a cervical epidural Racz catheter. Pain Physician. 2014;17:E381-E384. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Inamasu J, Nakatsukasa M. Blood patch for spontaneous intracranial hypotension caused by cerebrospinal fluid leak at C1-2. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2007;109:716-719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Shima K, Ishihara S, Tomura S. Pathophysiology and diagnosis of spontaneous intracranial hypotension. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2008;102:153-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Chen YC, Wang YF, Li JY, Chen SP, Lirng JF, Hseu SS, Tung H, Chen PL, Wang SJ, Fuh JL. Treatment and prognosis of subdural hematoma in patients with spontaneous intracranial hypotension. Cephalalgia. 2016;36:225-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Nardone R, Caleri F, Golaszewski S, Ladurner G, Tezzon F, Bailey A, Trinka E, Zuccoli G. Subdural hematoma in a patient with spontaneous intracranial hypotension and cerebral venous thrombosis. Neurol Sci. 2010;31:669-672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | de Noronha RJ, Sharrack B, Hadjivassiliou M, Romanowski CA. Subdural haematoma: a potentially serious consequence of spontaneous intracranial hypotension. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:752-755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Lai TH, Fuh JL, Lirng JF, Tsai PH, Wang SJ. Subdural haematoma in patients with spontaneous intracranial hypotension. Cephalalgia. 2007;27:133-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Dhillon AK, Rabinstein AA, Wijdicks EF. Coma from worsening spontaneous intracranial hypotension after subdural hematoma evacuation. Neurocrit Care. 2010;12:390-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Chen HH, Huang CI, Hseu SS, Lirng JF. Bilateral subdural hematomas caused by spontaneous intracranial hypotension. J Chin Med Assoc. 2008;71:147-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |