Published online Jul 16, 2013. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v1.i4.152

Revised: June 4, 2013

Accepted: June 8, 2013

Published online: July 16, 2013

Processing time: 163 Days and 17.1 Hours

A hepatic lymphangioma is a rare benign neoplasm and is usually associated with lymphangiomas of other viscera. A hepatic lymphangioma can be solitary, cystic or associated with multiple liver lesions and is characterized by cystic dilatation of lymphatic vessels in the hepatic parenchyma. A solitary lymphangioma is unusual. Here we report a rare case of a solitary huge primary hepatic cystic lymphangioma in a 42-year-old woman. It was discovered on routine physical examination and the patient had no obvious symptoms. Ultrasonography and computed tomography (CT) showed a giant “hepatic neoplasm” that occupied the right liver lobe. The lesion was approximately 20.0 cm × 15.0 cm × 10.0 cm in size and contained cystic and solid components. There were multiple septa inside the tumor, with some calcifications in the septa. Surgical resection was performed. Histological examination revealed multiple cystic structures lined with epithelial cells on the inner walls, accompanied by interstitial swelling and necrosis. The patient has now been followed up for nearly two years after surgery, with no recurrence to date.

Core tip: Lymphangiomas are congenital malformations of the lymphatic system. A hepatic lymphangioma is a rare benign neoplasm that is usually associated with lymphangiomas of other viscera. A solitary lymphangioma is unusual. Here, we report a rare case of a solitary huge primary hepatic cystic lymphangioma. It was discovered on routine physical examination and the patient had no obvious symptoms. The diagnosis was confirmed by histological examination. The patient has now been followed up for nearly two years after surgery and has had no recurrence.

- Citation: Zhang YZ, Ye YS, Tian L, Li W. Rare case of a solitary huge hepatic cystic lymphangioma. World J Clin Cases 2013; 1(4): 152-154

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v1/i4/152.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v1.i4.152

A hepatic lymphangioma is a rare benign tumor and is usually associated with lymphangiomas of other viscera. It can be solitary, cystic or associated with multiple liver lesions and is characterized by cystic dilatation of lymphatic vessels in the hepatic parenchyma[1]. It can occur at any age and the majority of lesions are found incidentally[2]. Surgical resection is normally performed due to the symptoms or because of concern about malignancy. In this report, we describe a rare case of a solitary huge primary hepatic lymphangioma which was incidentally found in a 42-year-old woman. We additionally provide a current literature review on this topic.

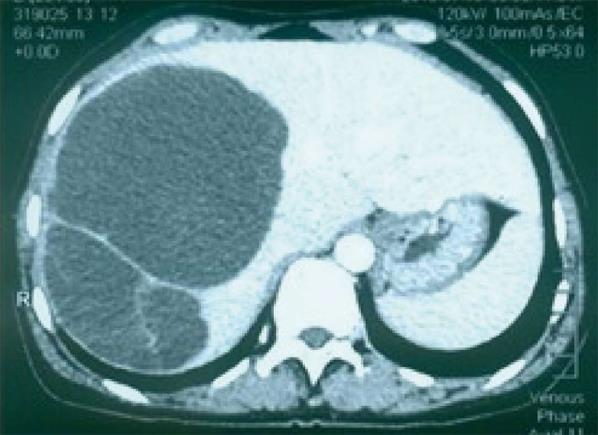

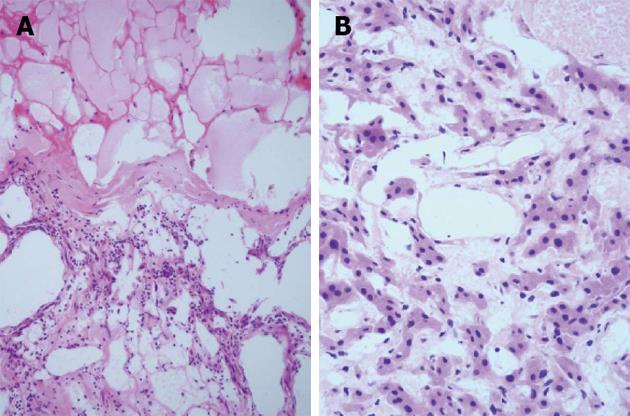

A 42-year-old woman was admitted because of a mass in the right lobe of her liver which was discovered on routine physical examination. There were no obvious symptoms, such as pain, fever, jaundice or weight loss. Ultrasonography showed a giant “hepatic neoplasm” occupying the right liver lobe. The mass measured approximately 20.0 cm×15.0 cm × 10.0 cm and contained cystic and solid components. There were multiple septa inside the tumor. There was no internal or external hepatic bile duct expansion. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) showed a huge, non-homogeneous, relatively well-defined, low density cystic mass with multiple septa occupying the right lobe of the liver. The inner margin was near the middle hepatic vein. There were some calcifications in the septa. There was no enhancement in either the arterial or venous phases in the cystic areas, but the septa were seemingly enhanced (Figure 1). Laboratory tests also did not produce any positive findings. Exploratory laparotomy revealed that the tumor was a 15.0 cm × 15.0 cm brown soft mass in the right lobe of the liver. Hemihepatectomy and cholecystectomy were performed (Figure 2). Histological examination showed that there were multiple cystic structures; two larger ones measured 6.0 cm × 3.0 cm × 1.0 cm and 13.0 cm × 10.0 cm × 3.0 cm, respectively, and contained coffee-like fluid. There were cystic structures lined with epithelial cells on the inner walls, accompanied by interstitial swelling and necrosis (Figure 3). Immunohistochemistry showed endothelium markers CD34(+), AFP(-), D2-40(-), Hepatocyte(-), CK117(-), CK8(focal+) and Ki67(< 1%+). The pathological diagnosis was liver lymphangioma. The patient has now been followed up for nearly two years post surgery, with no sign of any recurrence to date.

Lymphangiomas are the results of congenital malformations of the lymphatic system. The condition is due to obstruction of lymphatic fluid drainage between the cystic lymphatics and the central veins, or abnormal development of the lymphatic branches, or formation of separated lymphatics and cysts which result in lymphangiomas[1,2]. Lymphangiomas are typically featured in both malformations and neoplasms. Lymphangiomas have been classified into three types: simple lymphangioma, cavernous lymphangioma and cystic lymphangioma[3]. Other authors have divided lymphangiomas into five types: simple lymphangioma, cavernous lymphangioma, cystic lymphangioma, lymphangiohemangioma and lymphangiosarcoma[4]. Among these five types, cystic lymphangiomas are the most common. The fluid component of a lymphangioma can be serous or chylaceous, depending on the location of the lymphangioma. In the presence of hemorrhage or infection, a lymphangioma can be bloody or purulent. In the present case, the fluid was coffee-like, indicating that hemorrhage might have occurred (Figure 2).

More than 95% of lymphangiomas occur in the neck and axilla. Abdominal lymphangiomas are rare (less than 1%) and usually occur in the mesentery and retroperitoneum. Although hepatic lymphangiomas are considered as a subset of multiple abdominal lymphangiomas, they rarely occur in the liver alone. Hepatic lymphangiomas are single or multiple occurrences of lymphangiectasia, containing blood in the lumen and lined with endothelial cells which have inconspicuous nuclei on the inner walls[4-6]. Hepatic lymphangiomas usually cause liver tissue destruction due to extrusion of the normal liver tissue (Figure 3).

Normally, most hepatic lymphangiomas are found by routine physical examination or from other complaints and have no specific clinical presentation. Occasionally, abdominal pain is caused due to the compression of surrounding tissues or organs[1]. In the present case, the patient’s liver mass was discovered during her wellness physical examination; no other abnormalities were found. Ultrasonography or CT imaging may lead to a misdiagnosis of hepatic hemangioma or hepatic cystadenocarcinoma. Thickness of the cyst wall, number of cystic septations and internal echoes may be helpful to differentiate lymphangioma from other mesenteric cysts[7]. CT imaging can reveal the cystic characteristics. When containing chylous fluid, the cysts may manifest as a negative CT value. Other reports have also revealed that the characteristic CT imaging features of a lymphangioma are a cystic or multicystic lesion with no enhancement in the central region and enhancement in the septa. If a lymphangioma and hemangioma co-exist, the lesion will be enhanced. This feature correlates with the present case, in which there were no enhancement regions in the cystic areas but the septa were seemingly enhanced (Figure 1)[1,2,5]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of a lymphangioma usually shows a multiloculated heterogeneous mass with low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images because of the content of the lymphangioma[6]. MRI is very helpful for determining such characteristic features of a lesion because T2-weighted and heavily T2-weighted imaging are sensitive to the presence of water. However, when hemorrhage or infection occur, the CT value of the cystic region will rise and may lead to misdiagnosis[8]. The image as seen on MRI corresponds to dilated lymphatic spaces and is useful in differentiating a lymphangioma from a true solid neoplasm.

Lymphangiomas are benign hamartomas but have a risk of cancerization. Continuing enlargement can cause rupture. Surgical resection of lymphangiomas has been considered standard treatment. Histopathological examination from frozen section is helpful for intraoperative diagnosis if it is difficult to make a clear diagnosis during the operation. For huge or multiple lymphangiomas, liver transplantation is also considered[9].

The prognosis of hepatic lymphangiomas is good and patients have no need for further treatment after resection. It has been found that a lymphangioma rarely recurs or progresses[10]. In the present case, the patient has now been followed up for nearly two years and has had no sign of any recurrence to date.

| 1. | Matsumoto T, Ojima H, Akishima-Fukasawa Y, Hiraoka N, Onaya H, Shimada K, Mizuguchi Y, Sakurai S, Ishii T, Kosuge T. Solitary hepatic lymphangioma: report of a case. Surg Today. 2010;40:883-889. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kochin IN, Miloh TA, Arnon R, Iyer KR, Suchy FJ, Kerkar N. Benign liver masses and lesions in children: 53 cases over 12 years. Isr Med Assoc J. 2011;13:542-547. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Alqahtani A, Nguyen LT, Flageole H, Shaw K, Laberge JM. 25 years’ experience with lymphangiomas in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:1164-1168. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Chen CQ, Zhan WH, Wang JP, Chen ZX, Dong WG, Lan P, Peng JS. The clinical characteristics, diagnosis and treatment of abdominal lymphangioma. Chinese Journal of Practical Surgery. 2000;20:421-422. |

| 5. | Adachi S, Maruyama T, Suetomi T, Morishita Y, Otsuka M, Todoroki T, Fukao K. Retroperitoneal multiple lymphangioma with differential cyst contents causing hydronephrosis and biliary dilatation. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:397-400. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Abe H, Kubota K, Noie T, Bandai Y, Makuuchi M. Cystic lymphangioma of the pancreas: a case report with special reference to embryological development. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1566-1567. [PubMed] |

| 7. | de Perrot M, Rostan O, Morel P, Le Coultre C. Abdominal lymphangioma in adults and children. Br J Surg. 1998;85:395-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Choi WJ, Jeong WK, Kim Y, Kim J, Pyo JY, Oh YH. MR imaging of hepatic lymphangioma. Korean J Hepatol. 2012;18:101-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Qin Y, Ni Y, Wang CY, Wang CL. Diagnosis and treatment of the rare tumor-like lesions of liver. Anhui Medical Journal. 2009;30:157-159. |

| 10. | Datz C, Graziadei IW, Dietze O, Jaschke W, Königsrainer A, Sandhofer F, Margreiter R. Massive progression of diffuse hepatic lymphangiomatosis after liver resection and rapid deterioration after liver transplantation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1278-1281. [PubMed] |

P- Reviewers Abou-Jaoude M, George S, Zhang S S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Yan JL