Published online May 16, 2013. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v1.i2.71

Revised: March 5, 2013

Accepted: April 3, 2013

Published online: May 16, 2013

Processing time: 142 Days and 22.5 Hours

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic idiopathic inflammatory disease of gastrointestinal tract characterized by segmental and transmural involvement of gastrointestinal tract. Ileocolonic and colonic/anorectal is a most common and account for 40% of cases and involvement of small intestine in about 30%. The stomach is rarely the sole or predominant site of CD. To date there are only a few documented case reports of adults with isolated gastric CD and no reports in the pediatric population. Isolated stomach involvement is very unusual presentation accounting for less than 0.07% of all gastrointestinal CD. The diagnosis is difficult to establish in cases of atypical presentation as in isolated gastroduodenal disease. In the absence of any other source of disease and in the presence of nonspecific upper GI endoscopy and histological findings, serological testing can play a vital role in the diagnosis of atypical CD. Recent studies have suggested that perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody and anti-Saccharomycescervisia antibody may be used as additional diagnostic tools. The effectiveness of infliximab in isolated gastric CD is limited to only a few case reports of adult patients and the long-term outcome is unknown.

Core tip: Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic idiopathic inflammatory disease of gastrointestinal tract characterized by segmental and transmural involvement of gastrointestinal tract. The stomach is rarely the sole or predominant site of CD accounting for less than 0.07% of all gastrointestinal CD. Serological testing and careful histopathological examination by excluding other causes of granulomatous gastritis can play a vital role to arrive at the diagnosis of atypical CD.

- Citation: Ingle SB, Hinge CR, Dakhure S, Bhosale SS. Isolated gastric Crohn’s disease. World J Clin Cases 2013; 1(2): 71-73

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v1/i2/71.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v1.i2.71

In common presentations, the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease (CD) is usually based on a combination of typical clinical, laboratory, endoscopic and histopathological findings. However, the diagnosis is difficult to establish in cases of atypical presentation as in isolated gastric disease. In such a scenario other possible etiologies must be systematically ruled out in order to establish the correct diagnosis. These conditions may include Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection, tuberculosis, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs gastritis, Menetrier’s disease, gastrinoma, collagen vascular disease and lymphoma. Additional diagnostic strategy in atypical cases of inflammatory bowel disease is the use of anti-Saccharomycescervisia antibody (ASCA). This serological marker can be a helpful adjunctive tool in the diagnostic process despite the test’s limitations.

Treatment regimens for gastric CD have been poorly studied. The routine treatment of inflammatory gastritis in CD includes the concomitant use of acid-suppressive drugs and immunomodulators such as ASCA products or steroids. In recent years infliximab [anti-tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)] has become an important addition to the therapeutic options in CD. The effectiveness of infliximab in isolated gastric CD is limited to only a few case reports of adult patients and the long-term outcome isunknown[1-3].

In most cases of CD the presentation, workup and diagnosis run a familiar and substantiating course. The symptoms of gastric CD are nausea, vomiting, epigastric pain and weight loss[2,4]. These symptoms arise from peptic ulcers and or obstruction in the outlet of the stomach[5]. A clinically symptomatic disease, however, is seen in 4% of cases[6]. Sometimes, however, this disease can manifest in an entirely non-specific and unusual manner. Uncommon presentations of CD may manifest as a single symptom or sign, such as impairment of linear growth, delayed puberty, perianal disease, mouth ulcers, clubbing, chronic iron deficiency anemia or extra-intestinal manifestations preceding the gastrointestinal symptoms, mainly arthritis or arthralgia, primary sclerosing cholangitis, pyoderma gangrenosum and rarely osteoporosis. In such cases, the diagnosis is challenging and can remain elusive for some time.

The stomach is rarely the sole or predominant site of CD. To date there are only a few documented case reports of adults with isolated gastric CD and no reports in the pediatric population. Normally, the diagnosis of CD is based on clinical presentation, radiological abnormalities of the small bowel, gastroscopy and colonoscopy findings and non-specific or typical pathological features.

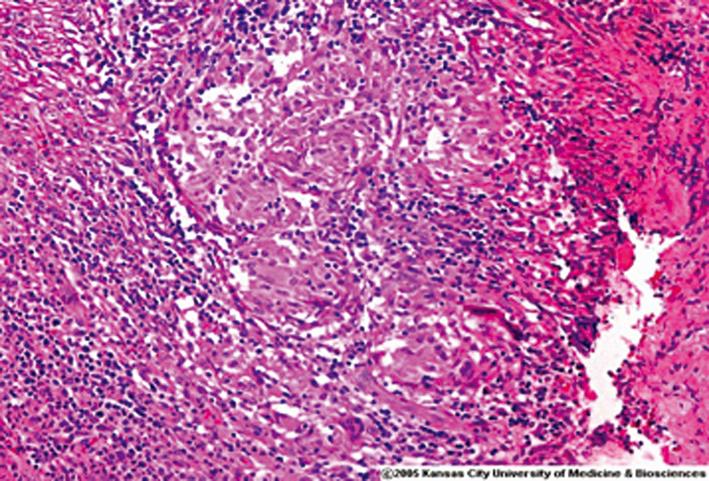

Radiology studies in gastroduodenal Crohn’s normally demonstrate similar features to those found in more distal CD, such as thickened folds, ulcers, nodularity, stenosis and distorted anatomy. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in gastric CD may be grossly normal or it may reveal various combinations of edema, erythema, ulcers, nodularity and cobblestone appearance.The antrum is most frequently involved, while the proximal stomach is often spared. Gastric biopsies have poor specificity and the changes of non-specific gastritis may be seen in other conditions such as H. pylori infection. Discovery of granulomatous gastritis (Figure 1) might help to narrow the differential diagnosis to CD, tuberculosis, malignancy and collagen vascular disease. Interestingly, however, granulomas are only identified in 3%-24% of the biopsies and repeat biopsies do not result in higher rates of granuloma discovery[7]. However, the marked edematous, inflammed and ulcerated regions with cobblestone appearance and inflammatory pseudopolyps found mainly in the antrum on endoscopy are at least suggestive of CD.

In the absence of any other source of disease and in the presence of nonspecific upper endoscopy and histological findings, serological testing can play an important role in the diagnosis of atypical CD. Recent studies have suggested that perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (pANCA) and ASCA may be used as additional diagnostic tools for patients with suspected inflammatory bowel disease and help to differentiate between CD and ulcerative colitis. Indeed, ASCA is detected in 55%-60% of children and adults with CD and only 5%-10% of controls with other gastrointestinal disorders. This finding pANCA highlights the relatively good specificity but poor sensitivity of ASCA as a marker for CD. pANCA on the other hand is more specific to ulcerative colitis and the combination of a positive ASCA test with a negative pANCA test has a positive predictive value of 96% and a specificity of 97% for CD. Inaddition, some NOD2/CARD15 gene polymorphisms, particularly L1007P homozygosity, were found to be associated with gastroduodenal CD and with younger age at diagnosis. It is possible that these genes might also help to support the diagnosis in the atypical presentation of CD in the future.

Infliximab, a monoclonal antibody to TNF-α, is often used in cases of steroid refractory CD. The role of infliximab in treating patients with gastric CD has scarcely been studied. In one case series, infliximab was effective in healing ulcers in two patients[2], but the development of lung cancer in one and surgery in the other necessitated stopping the treatment. In another case study the symptoms in a patient with diffuse mucosal thickening and ulceration throughout the antrum and duodenum continued despite prednisone and a twice-daily dose of a proton pump inhibitor. Treatment with infliximab led to marked improvement within 1 wk[2]. Surgical therapy in CD can be indicated for ulcers not responding to medical therapy, massive bleeding, in gastric outlet obstructions for which balloon dilatation is unsuccessful, or in cases where gastric fistulas have developed[5]. Recurrence after surgical therapy is common, and re-operations are frequently required[7,8].

In summary,atypical cases with non-conclusive clinical, endoscopic and pathological findings, the ASCA test could be helpful in the diagnostic process. Infliximab may be an effective treatment in cases of severe isolated gastropathy due to CD.

| 1. | Ingle SB, Pujari GP, Patle YG, Nagoba BS. An unusual case of Crohn’s disease with isolated gastric involvement. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:69-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Grübel P, Choi Y, Schneider D, Knox TA, Cave DR. Severe isolated Crohn’s-like disease of the gastroduodenal tract. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:1360-1365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Firth MG, Prather CM. Unusual gastric Crohn’s disease treated with infliximab - a case report. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:S190. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Cary ER, Tremaine WJ, Banks PM, Nagorney DM. Isolated Crohn’s disease of the stomach. Mayo Clin Proc. 1989;64:776-779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Banerjee S, Peppercorn MA. Inflammatory bowel disease. Medical therapy of specific clinical presentations. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2002;31:185-202, x. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gray RR, St Louis EL, Grosman H. Crohn’s disease involving the proximal stomach. Gastrointest Radiol. 1985;10:43-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wagtmans MJ, Verspaget HW, Lamers CB, van Hogezand RA. Clinical aspects of Crohn’s disease of the upper gastrointestinal tract: a comparison with distal Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1467-1471. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Nugent FW, Roy MA. Duodenal Crohn’s disease: an analysis of 89 cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:249-254. [PubMed] |

P- Reviewer Deepak P S- Editor Zhai HH L- Editor A E- Editor Zheng XM