Published online Mar 20, 2026. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v16.i1.109473

Revised: June 10, 2025

Accepted: September 8, 2025

Published online: March 20, 2026

Processing time: 273 Days and 3.1 Hours

Hip fractures are a major cause of morbidity and mortality among older indivi

To compare the Nottingham Hip Fracture Score (NHFS) and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE)-II score in predicting 30-day mortality among 182 geriatric patients (≥ 60 years) undergoing elective hip fracture surgery at Tata Main Hospital, Jamshedpur, India.

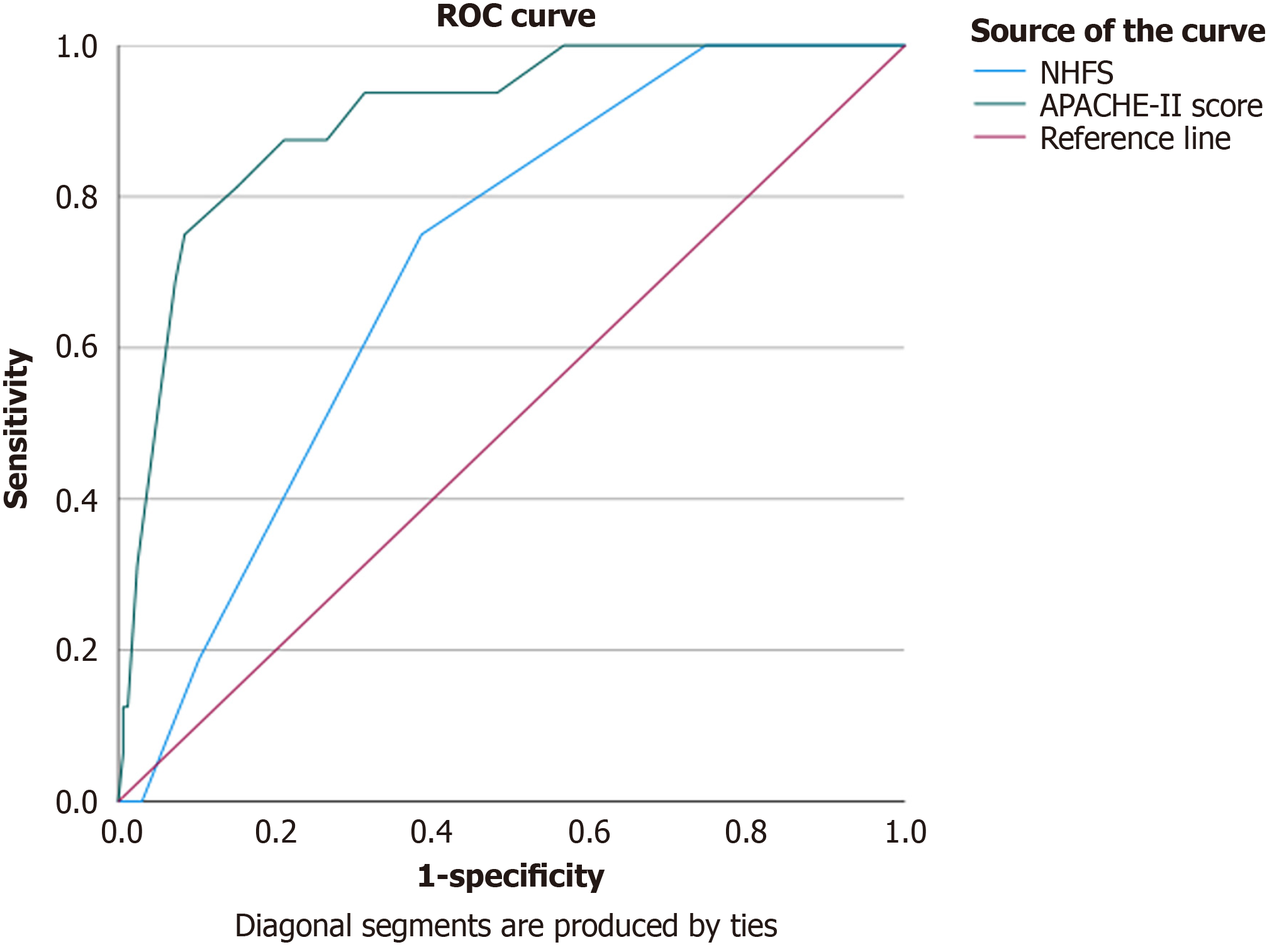

NHFS and APACHE-II scores were calculated preoperatively. Patients were followed up for 30 days post-surgery to determine mortality outcomes. Statistical analysis, including receiver operating characteristic curve analysis, was performed to assess the predictive accuracy of both scores.

Results indicated that APACHE-II demonstrated superior predictive ability compared to NHFS. The study also assessed secondary outcomes such as ventilator and inotropic support, acute kidney injury (AKI), cardiac morbidity, pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, and length of hospital stay (LOS). APACHE-II showed superior performance in predicting the need for ventilator support and AKI.

Both scores showed significant discrimination for ventilator and inotropic support and LOS but not for AKI. The findings highlight the importance of comprehensive risk stratification for managing geriatric patients with hip fracture.

Core Tip: This prospective observational study at Tata Main Hospital in Jamshedpur, India, evaluated the Nottingham Hip Fracture Score (NHFS) and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE)-II score for predicting 30-day mortality in 182 geriatric patients with hip fracture (≥ 60 years). The study assessed the primary (mortality prediction) and secondary objectives, including the requirement for ventilator/ionotropic support and monitoring for acute kidney injury and other complications. Preoperatively, the NHFS and APACHE-II scores were calculated, and patients were followed up for a minimum of 30 days post-surgery. Statistical analyses included receiver operating characteristic curves, area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity, specificity, and P value using Statistica. Results indicated that NHFS showed moderate predictive accuracy (AUC = 0.709, P = 0.006), whereas APACHE-II demonstrated excellent predictive ability (AUC = 0.904, P < 0.001). Significant predictors of mortality included the APACHE-II score, NHFS, mean arterial pressure, pH, respiratory rate, and serum creatinine levels. Although age and gender showed notable trends, they were not statistically significant. The findings indicate that the APACHE-II score is a strong predictor of 30-day mortality following hip fracture surgery, highlighting the importance of incorporating multiple factors for effective prediction.

- Citation: Nag DS, Prasad S, Sahu S, Laik JK, Swain A, Anand R, Saroha S, Mahanty PR, Kumar H, Mistari W. Nottingham Hip Fracture Score and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation-II: Predicting 30-day mortality in elderly hip fracture. World J Methodol 2026; 16(1): 109473

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v16/i1/109473.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v16.i1.109473

Hip fractures are a major public health concern, particularly in older individuals[1]. The projected increase in hip fracture incidence driven by aging populations and the increasing prevalence of osteoporosis poses substantial challenges for healthcare systems, leading to increased morbidity and mortality[2,3]. The effects of hip fracture extend beyond the immediate injury, affecting mobility, quality of life, and cognitive function. Patients often experience declines in activities of daily living, increased dependence, and a higher risk of delirium and long-term cognitive impairment[4].

Postoperative mortality rates following hip fracture surgery can reach 5%–10% within 30 days and may rise to 33% within a year[5-7]. Delays in surgical intervention significantly increase these rates, highlighting the need for accurate risk assessment.

Various scoring systems, such as the Nottingham Hip Fracture Score (NHFS) and the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation-II (APACHE-II) score, can help predict mortality risk[8,9]. The NHFS uses seven preoperative variables [age, sex, hemoglobin levels, Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score, institutionalization status, comorbidities, and malignancy] for straightforward assessment of frailty among patients[10]. In contrast, the APACHE-II score integrates 12 physiological variables, offering a more comprehensive but complex assessment of illness severity[11,12].

Both scoring systems have shown efficacy in predicting 30-day mortality; however, comparative analyses of their effectiveness remain limited[9,12]. Addressing this knowledge gap is vital for identifying the most effective risk stratification tools, ultimately enhancing personalized care strategies and patient outcomes. The present study aimed to address this gap by providing essential insights into hip fracture management among geriatric patients. This study directly addresses this knowledge gap and is possibly the first such study to directly compare the predictive accuracy of the APACHE-II and NHFS, specifically for mortality.

Our research examined whether there is a 10% difference in NHFS and APACHE-II scores in predicting 30-day mortality among geriatric patients (aged ≥ 60 years) undergoing hip fracture surgery. This comparative analysis aimed to determine which scoring system more accurately predicts postoperative mortality and to support clinical decision-making for improved patient care. The results of this study can potentially influence resource allocation and treatment strategies for hip fracture management.

This study employed a prospective observational design. The prospective approach allowed real-time data collection from the time of patient admission until the 30-day follow-up or the occurrence of death. The observational nature of the study ensured that data collection occurred without intervention in the standard clinical care pathway, minimizing bias that could arise from experimental manipulation. This study aimed to compare the NHFS and APACHE-II scores for predicting 30-day mortality among geriatric patients (≥ 60 years) undergoing elective hip fracture surgery. Interobserver bias in APACHE-II scoring was reduced by implementing strict guidelines and training programs. The NHFS minimizes interobserver bias by relying on objective, routinely available data at admission, including age, sex, hemoglobin levels, comorbidities, living status, and cognitive function assessment.

The study population comprised geriatric patients aged ≥ 60 years admitted to Tata Main Hospital, Jamshedpur, India, between June 20, 2022, and June 19, 2023, for elective hip fracture surgery. Inclusion criteria included patients aged ≥ 60 years, undergoing elective surgery for hip fracture, and who provided informed consent. Exclusion criteria were patients younger than 60 years, those with hip fractures not undergoing invasive surgery, those scheduled for implant removal of a previously healed hip fracture, and those undergoing re-exploration surgery during the same admission as the initial hip fracture surgery. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee of Tata Main Hospital before study commencement, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients. This study was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT06598566). A total of 182 patients met the inclusion criteria.

Data were collected prospectively from patients’ medical records. Preoperative data included demographic information (age and sex) and clinical measurements [temperature, mean arterial pressure (MAP), heart rate, respiratory rate, partial pressure of oxygen, arterial pH, serum sodium levels, serum potassium levels, serum creatinine levels, hematocrit, and total leukocyte count], which were collected within 2 days of admission. Preoperative assessments also included the NHFS and APACHE-II scores. For NHFS, data were obtained on age, sex, hemoglobin level on admission, MMSE score, institutional living status, number of comorbidities, and presence of malignancy, as outlined in the original scoring system[13]. APACHE-II score was calculated using the established scoring system, which includes physiological and chronic health variables. Postoperative data were collected for a minimum of 30 days after surgery to determine 30-day mortality outcomes. Secondary outcome measures included the need for postoperative ventilator support, the need for ionotropic support, acute kidney injury (AKI), cardiac morbidity, pulmonary embolism (PE) or deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and length of hospital stay (LOS). AKI was defined using Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes criteria (2012 guidelines)[14].

The study data were analyzed using Statistica version 13 (TIBCO Software Inc.). The distribution of continuous variables was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test. For normally distributed data, the independent samples t-test was used to compare means between survivors and non-survivors, whereas the Mann–Whitney U test was used for non-normally distributed data. Categorical variables were analyzed using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was used to evaluate differences in NHFS and APACHE-II scores between survivors and non-survivors, revealing statistically significant differences. Sensitivity, specificity, and optimal cutoff points were determined from this analysis. Secondary outcomes, such as postoperative ventilator support, ionotropic support, and AKI, were also assessed. The LOS was analyzed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. There were no specific incidences of cardiac morbidity, PE, or DVT. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Multivariate logistic regression was performed to address potential confounders.

This prospective observational study analyzed data from 182 geriatric patients aged ≥ 60 years undergoing elective hip fracture surgery at Tata Main Hospital between June 2022 and June 2023. The cohort had a diverse age distribution, with 31.9% aged 60–70 years, 44.0% aged 71–80 years, and 24.2% aged over 80 years. Sex distribution was relatively balanced (53.8% female and 46.1% male). Baseline characteristics revealed that 63.7% of the patients had more than two comorbidities, and 47.8% had hemoglobin levels below 10 g/dL. The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification indicated that most patients had moderate–to-severe systemic disease, approximately 3.3% had a malignancy, and almost 54% had organ insufficiency. The mean MMSE score of the cohort was 6.07, with most patients diagnosed with an intertrochanteric fracture. The average LOS was < 7 days with nearly 16% of patients, and the majority stayed between 7 days and 15 days (72.5%). The overall 30-day mortality rate was 8.8%.

Of the patients, 65 hip fractures were treated with proximal femoral nailing, 57 underwent fixation with a dynamic hip screw, and 50 patients underwent hemiarthroplasty. Among the remaining 10 patients, 2 underwent total hip arthroplasty, 3 underwent bipolar hip arthroplasty, 3 underwent fixation with a dynamic condylar screw, 1 underwent open reduction and internal fixation, and 1 underwent fixation with cannulated cancellous screws. The demographic characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1.

| Statistics (categorical variables) | |||

| Name of characteristics (n = 182) | Categories | Numbers | Percentage |

| Age in year | 60-70 years | 58 | 31.9 |

| 71-80 years | 80 | 44.0 | |

| > 80 years | 44 | 24.2 | |

| Sex | Female | 98 | 53.8 |

| Male | 84 | 46.1 | |

| Hemoglobin in gm/dL | > 10 | 95 | 52.2 |

| ≤ 10 | 87 | 47.8 | |

| Length of stay in days | < 7 | 29 | 15.9 |

| 7-15 | 132 | 72.5 | |

| 16-30 | 21 | 11.5 | |

| Malignancy | No | 176 | 96.7 |

| Yes | 6 | 3.3 | |

| Number of comorbidities | < 2 | 66 | 36.3 |

| ≥ 2 | 116 | 63.7 | |

| Admission Mini Mental Test Score | > 6/10 | 100 | 54.9 |

| ≤ 6/10 | 82 | 45.1 | |

| Diagnosis (fracture) | IT left femur | 60 | 33.0 |

| IT right femur | 65 | 35.7 | |

| Left acetabulum | 1 | 0.5 | |

| NOF left | 29 | 15.9 | |

| NOF right | 27 | 14.8 | |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists | II | 92 | 50.5 |

| III | 88 | 48.4 | |

| IV | 2 | 1.1 | |

| H/O organ insufficiency | No | 84 | 46.2 |

| Yes | 98 | 53.8 | |

| Renal failure | No | 148 | 81.3 |

| Acute renal failure | 13 | 7.1 | |

| Chronic renal failure | 21 | 11.5 | |

| Outcome | Survived | 166 | 91.2 |

| Mortality | 16 | 8.8 | |

Several variables demonstrated statistically significant associations with 30-day mortality. Higher NHFS and APACHE-II scores were significantly associated with increased mortality. Patients with hemoglobin levels below 10 g/dL had significantly higher mortality rates. The LOS was significantly associated with survival. A history of organ insufficiency and the presence of renal failure were also significantly associated with increased mortality. The comparison of variables between survivors and non-survivors is summarized in Table 2.

| Comparison of continuous variables with outcome | |||||

| Name of characteristics at admission (n = 182) | Survived (n = 166) | Mortality (n = 16) | P value | ||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Weight | 61.44 | 5.56 | 61.88 | 16.78 | 0.182 |

| Nottingham Hip Fracture Score | 5.23 | 1.10 | 5.94 | 0.68 | 0.004a |

| Temp (rectal) (°C) | 36.64 | 0.35 | 36.74 | 0.36 | 0.163 |

| Mean arterial pressure | 100.47 | 16.49 | 110.21 | 18.71 | 0.028a |

| Heart rate/minute | 84.01 | 14.71 | 93.31 | 28.29 | 0.262 |

| Respiratory rate/minute | 15.66 | 2.74 | 18.38 | 2.68 | < 0.001a |

| Partial pressure of oxygen | 92.99 | 29.00 | 96.48 | 30.85 | 0.837 |

| PH | 7.40 | 0.05 | 7.34 | 0.09 | 0.002a |

| Serum Na+ (mEq/L) | 130.91 | 6.63 | 129.69 | 8.02 | 0.498 |

| Serum K+ (mEq/L) | 4.08 | 0.58 | 4.19 | 0.80 | 0.663 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.12 | 0.62 | 1.42 | 0.46 | 0.003a |

| Hematocrit (%) | 31.11 | 4.73 | 30.00 | 3.95 | 0.252 |

| Total leukocyte count (total/mm3) | 9486.14 | 3219.32 | 11243.75 | 4120.84 | 0.080 |

| Glasgow Coma Score | 14.90 | 0.45 | 14.13 | 1.02 | < 0.001a |

| Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation-II score | 10.11 | 3.79 | 16.94 | 3.26 | < 0.001a |

Both the NHFS and APACHE-II scores showed predictive capability for 30-day mortality; however, the findings indicated that APACHE-II has better predictive capability. The area under the curve (AUC) for NHFS was 0.709 (95%CI: 0.60-0.81), with a sensitivity of 75.00%, specificity of 61.00%, and cutoff value of 6. The AUC for APACHE-II was significantly higher at 0.904 (95%CI: 0.83-0.97), with a sensitivity of 87.50%, specificity of 74.00%, and cutoff value of 13, indicating a more accurate prediction model. Although both models could be used to assess mortality risk, the statistical differences indicate that APACHE-II is a better predictor (Figure 1).

NHFS: The ROC curve analysis for NHFS provides insights into its predictive ability for a particular outcome. The AUC for NHFS was calculated to be 0.709. The AUC value ranges from 0 to 1, where a higher value indicates better discriminatory power of the variable. In this case, an AUC of 0.709 indicates that NHFS has a moderate level of predictive accuracy.

The 95%CI for the AUC is 0.60-0.81. This interval indicates the range within which the true AUC value is likely to fall. The lower and upper bounds indicate the possible values the AUC may take with 95%CI.

The P value associated with NHFS was 0.006, which is used to test the null hypothesis that the AUC is equal to 0.05 (which represents no discriminatory power). In this case, the P value was less than the typical significance level of 0.05, indicating that the ability of NHFS to predict the outcome was statistically significant. The sensitivity of NHFS was calculated to be 75.00%, and the specificity was 61.00%. Sensitivity measures the proportion of true positives correctly identified by the model, whereas specificity measures the proportion of true negatives correctly identified. These values provide information about the balance between correctly identifying positive and negative cases.

The cutoff value for NHFS was 6. This value represents the threshold at which the model differentiates between positive and negative cases. In other words, if an individual’s NHFS score is > 6, the model is more likely to predict a specific outcome (Table 3).

APACHE-II score: The ROC curve analysis for the APACHE-II score indicates its predictive performance. The AUC for APACHE-II was calculated to be 0.904. With an AUC value close to 1, the APACHE-II score demonstrated excellent discriminatory power in predicting the outcome. The 95%CI for the AUC ranged from 0.83 to 0.97, indicating a range within which the true AUC value is likely to fall. The narrow CI range further demonstrates the model’s accuracy. The P value associated with APACHE-II was < 0.001, which indicates that APACHE-II was highly significant in predicting the outcome. The small P value indicates that the observed relationship between APACHE-II and the outcome was unlikely to have occurred by chance. The sensitivity and specificity of APACHE-II were 87.50% and 74.00%, respectively. These values indicate that APACHE-II is effective for correctly identifying both positive and negative cases. The cutoff value for APACHE-II is 13, which represents the threshold beyond which the model predicts a specific outcome. If an individual’s APACHE-II score exceeds 13, the model is more likely to predict a particular outcome.

The comparison of the APACHE-II and NHFS scores revealed valuable insights into their predictive accuracy for the risk of mortality. The APACHE-II score was significantly associated with the risk of mortality (P < 0.001). The Hosmer–Lemeshow test indicates a good fit for the model, with a statistic of χ² = 5.85 and a P value of 0.66, indicating that the predictions are consistent with observed outcomes. In contrast, the NHFS score also demonstrated a significant association with the risk of mortality (P = 0.015), although its model fit was weaker than that of the APACHE-II score. The Hosmer–Lemeshow test yielded a statistic of χ² = 5.37 and a P value of 0.15, indicating an acceptable model fit, although with slightly lower reliability. Overall, the APACHE-II model showed superior predictive accuracy for mortality risk assessment compared to that of the NHFS model.

To determine the optimal cutoff thresholds for predicting mortality using the APACHE-II and NHFS scores, Youden’s index, which identifies the point on the ROC curve that maximizes the sum of sensitivity and specificity, was also evaluated. For APACHE-II, the optimal cutoff threshold was approximately 15.5. At this point, the sensitivity was 0.75 and specificity was approximately 0.92. For NHFS, the optimal cutoff threshold was approximately 5.5. At this point, the sensitivity was 0.75 and specificity was approximately 0.62. This indicates that patients with an APACHE-II score > 15.5 are at higher risk of mortality, as are those with an NHFS score > 5.5; however, the APACHE-II score demonstrates better specificity.

The APACHE-II score demonstrates superior performance compared to the NHFS across various clinical outcomes. Specifically, for ventilatory support, APACHE achieved an AUC of 0.838, which was significantly higher than NHFS, which achieved 0.686. Similarly, in terms of inotropic support, the APACHE score (AUC = 0.751) outperformed NHFS (AUC = 0.600). When assessing the prediction of AKI, APACHE excelled with an AUC of 0.845 compared with NHFS’s 0.698. Additionally, for LOS, although both scores exhibited weak positive correlations, APACHE exhibited a slightly stronger correlation (P = 0.356) than NHFS (P = 0.207). Overall, the APACHE-II score consistently exhibited better discriminatory ability than NHFS, particularly in predicting AKI and the need for ventilator support. Both scoring systems showed statistically significant discrimination for ventilator support, inotropic support, and LOS (P < 0.05). For AKI, although both scores showed good discrimination (particularly APACHE with AUC = 0.845), the difference between the scores was not significant (P = 0.117). APACHE consistently demonstrated stronger discriminatory ability across all outcomes than NHFS. Table 4 presents the discriminatory abilities of APACHE-II and NHFS scores for various outcomes, along with the statistical significance of their performance in predicting secondary outcomes.

| Outcome | APACHE-II | NHFS | APACHE-II (P value) | NHFS (P value) |

| Ventilatory support (AUC) | 0.838 | 0.686 | 0.00264 | 0.00264 |

| Inotropic support (AUC) | 0.751 | 0.6 | 0.00063 | 0.00063 |

| Acute kidney injury (AUC) | 0.845 | 0.698 | 0.117 | 0.117 |

| Length of stay (Spearman's P) | 0.356 | 0.207 | 8.41E-07 | 0.00513 |

This prospective study included 182 geriatric patients with hip fracture. Most patients had multiple comorbidities, moderate-to-severe systemic disease, and short LOS. The 30-day mortality rate was 8.8%. The NHFS and APACHE-II scores were predictive of mortality, with APACHE-II demonstrating better predictive capability. Lower hemoglobin levels, organ insufficiency, and renal failure were associated with increased mortality. APACHE-II also showed superior performance in predicting secondary outcomes such as the need for ventilator support and AKI compared to NHFS.

The analysis of factors affecting survival outcomes highlights the crucial role of age and specific clinical indicators in determining patient prognosis. Age appears to be a critical factor, with individuals aged 60–80 years showing higher survival rates than older patients, particularly those above 80 years who exhibit increased mortality risk. This trend indicates that advanced age can adversely affect survival outcomes. Gender appears to play a negligible role in this context, indicating that survival rates are more influenced by other clinical variables.

The NHFS has been independently validated in various studies, revealing its efficacy as a predictor of 30-day mortality. For instance, Rushton et al[15] analyzed 1079 hip fracture cases in the United Kingdom, with a mean age of 83 years and 26% male patients. Tilkeridis et al[16] conducted a similar validation in a Greek population, confirming the NHFS’s utility in predicting outcomes among patients over a 3-year period, with a mean age of 80.82 years. These studies affirm the NHFS’s relevance across diverse demographics and geographic locations.

Hemoglobin levels were also found to be a critical predictor of survival. Patients with hemoglobin levels > 10 g/dL demonstrated significantly better survival odds, indicating that maintaining adequate hemoglobin levels is crucial for overall health[17]. Although some studies have shown an association between hematocrit levels and all-cause mortality in geriatric patients with hip fractures[18], our study did not show significant differences between survivors and those who succumbed within 30 days. Similarly, prolonged hospital stays (16–30 days) are correlated with higher mortality rates, indicating that extended exposure to medical settings may increase the likelihood of complications that negatively affect patient outcomes[19]. This association underscores the importance of efficient hospital management and timely intervention.

Further insights were obtained by recognizing the strong influence of malignancy on mortality rates. Patients with malignancies had markedly higher mortality rates, emphasizing the need to consider underlying health conditions when evaluating patient prognosis. Additionally, the analysis of comorbidities revealed a direct relationship between an increased number of coexisting health problems and mortality rates, highlighting the cumulative effect of multiple health issues. The ASA classification system, which evaluates systemic disease severity, also proved valuable, as patients in ASA class II exhibited better survival rates than those in higher classifications. Our study showed that higher MAP, higher respiratory rates, higher serum creatinine levels, and lower Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) scores were significantly associated with 30-day mortality among geriatric patients with hip fractures. These findings are consistent with those of similar studies on the mortality risk in geriatric patients with hip fractures[20-23].

The predictive power of scoring systems such as NHFS and APACHE-II cannot be overstated. The NHFS exhibited moderate predictive accuracy for mortality, whereas APACHE-II exhibited excellent discrimination and sensitivity, making it a robust tool for assessing patient outcomes. Recent studies have compared these models, with NHFS emerging as the preferred choice in clinical settings because of its ease of implementation and reliable predictive capabilities[24-26]. Continuous variables such as MAP, serum creatinine levels, and GCS scores further delineate the difference in outcomes between survivors and non-survivors, emphasizing the multifaceted factors influencing mortality. The APACHE-II score is a valuable tool for predicting mortality in geriatric patients with hip fractures because of several reasons. It provides a comprehensive assessment of a patient’s physiological status, considering various clinical parameters, such as heart rate, blood pressure, and age, that are crucial for older adults with multiple comorbidities. It assigns a score based on various physiological measurements and past medical history. Previous studies have reported its reliability in predicting mortality after geriatric hip fractures[27-29].

Although various studies have validated NHFS or APACHE-II independently for risk prognostication in hip fractures, only one study has compared the APACHE-II score with NHFS for mortality up to 1 year after surgery[27]. It showed that APACHE-II and Portsmouth Physiological and Operative Severity Score for the enumeration of Mortality and Morbidity were significantly better than ASA, Charlson Comorbidity Index, and NHFS for predicting mortality and can be used to predict mortality in older individuals with hip fractures[27]. This is the first study to compare APACHE-II score with NHFS for mortality. However, our findings are consistent with those of Tian et al[27], who concluded that although NHFS and APACHE-II scores are both valuable tools for risk stratification, APACHE-II score exhibits enhanced predictive accuracy, which significantly improves the ability to identify high-risk patients and aids in clinical decision-making. The study is limited by its single-center design, potentially restricting the generalizability of the findings to other populations and healthcare settings. The sample size of 182 patients, although adequate, may not be large enough to detect subtle differences between the NHFS and APACHE-II scoring systems. The focus on 30-day mortality outcomes provides only a short-term perspective, and longer-term outcomes were not assessed. Further multicenter trials with larger sample sizes across diverse geographic locations and longer follow-up periods are needed to validate our findings.

Regarding secondary outcomes, both the NHFS and APACHE-II scores served as effective tools for risk stratification, with each demonstrating significant discrimination for ventilator support, inotropic support, and LOS (P < 0.05). Regarding AKI, both scores exhibited good discrimination, particularly APACHE-II with an AUC of 0.845; however, the difference between the two scores was not significant (P = 0.117). Notably, APACHE-II consistently exhibited stronger discriminatory capability across all outcomes than NHFS.

Implementing APACHE-II in lower-resource settings presents substantial barriers. The complexity of data collection, including the 12 physiological variables, requires consistent access to laboratory facilities and monitoring equipment, which may be limited or unavailable. Staff training on APACHE-II scoring and data interpretation is essential but is frequently lacking. Furthermore, the time required for comprehensive data collection can strain already burdened healthcare personnel, potentially affecting workflow and accuracy. Overcoming these challenges necessitates simplified data collection protocols, targeted training programs, and resource allocation to ensure that basic monitoring facilities are available. The finding that APACHE-II is a superior predictor of mortality after hip fracture surgery could prompt a shift in clinical practice toward its use in resource allocation and patient management. Hospitals may prioritize intensive care resources for patients identified as high-risk by APACHE-II, potentially improving outcomes. In settings where both scores are feasible, use of APACHE-II can lead to more informed decisions regarding surgical timing and aggressiveness of postoperative care. It also highlights the need for resource investment to support the collection and use of these scores in clinical practice.

In conclusion, the ROC curve results for NHFS and APACHE-II provide valuable information about their predictive abilities. NHFS demonstrated a moderate level of predictive accuracy, with statistically significant results, whereas APACHE-II demonstrated a high AUC, strong statistical significance, and excellent sensitivity and specificity values. These findings indicate that APACHE-II is a key determinant of outcome, making it a valuable tool for predicting outcomes.

This study highlights the complex interplay of multiple factors in predicting 30-day mortality among geriatric patients undergoing hip fracture surgery. Although the NHFS and APACHE-II scores are valuable tools for risk stratification, our findings indicate that the APACHE-II score demonstrates superior predictive accuracy, offering substantial potential for identifying high-risk patients and guiding clinical decision-making. The combination of both measures may prove more effective. Furthermore, modifiable factors such as hemoglobin levels and the clinical management of comorbidities and organ dysfunction play critical roles in improving patient outcomes.

| 1. | Lisk R, Yeong K, Fluck D, Fry CH, Han TS. The Ability of the Nottingham Hip Fracture Score to Predict Mobility, Length of Stay and Mortality in Hospital, and Discharge Destination in Patients Admitted with a Hip Fracture. Calcif Tissue Int. 2020;107:319-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chandran M, Brind'Amour K, Fujiwara S, Ha YC, Tang H, Hwang JS, Tinker J, Eisman JA. Prevalence of osteoporosis and incidence of related fractures in developed economies in the Asia Pacific region: a systematic review. Osteoporos Int. 2023;34:1037-1053. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sing CW, Lin TC, Bartholomew S, Bell JS, Bennett C, Beyene K, Bosco-Lévy P, Chan AHY, Chandran M, Cheung CL, Doyon CY, Droz-Perroteau C, Ganesan G, Hartikainen S, Ilomaki J, Jeong HE, Kiel DP, Kubota K, Lai EC, Lange J, Lewiecki EM, Liu J, Man KKC, Mendes de Abreu M, Moore N, O'Kelly J, Ooba N, Pedersen AB, Prieto-Alhambra D, Shin JY, Sørensen HT, Tan KB, Tolppanen AM, Verhamme KMC, Wang GH, Watcharathanakij S, Zhao H, Wong ICK. Global epidemiology of hip fractures: a study protocol using a common analytical platform among multiple countries. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e047258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Van Heghe A, Mordant G, Dupont J, Dejaeger M, Laurent MR, Gielen E. Effects of Orthogeriatric Care Models on Outcomes of Hip Fracture Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Calcif Tissue Int. 2022;110:162-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 31.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Safety of disinvestment in mid- to late-term follow-up post primary hip and knee replacement: the UK SAFE evidence synthesis and recommendations. Southampton (UK): National Institute for Health and Care Research; 2022 Jun. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Roche JJ, Wenn RT, Sahota O, Moran CG. Effect of comorbidities and postoperative complications on mortality after hip fracture in elderly people: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ. 2005;331:1374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 970] [Cited by in RCA: 1040] [Article Influence: 49.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gundel O, Thygesen LC, Gögenur I, Ekeloef S. Postoperative mortality after a hip fracture over a 15-year period in Denmark: a national register study. Acta Orthop. 2020;91:58-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wiles MD, Moran CG, Sahota O, Moppett IK. Nottingham Hip Fracture Score as a predictor of one year mortality in patients undergoing surgical repair of fractured neck of femur. Br J Anaesth. 2011;106:501-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bujaković T, Delibegović S. Can the APACHE II score be used to assess the risk of mortality in the elderly with hip fractures? Med Glas (Zenica). 2025;22:127-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Forssten MP, Cao Y, Mohammad Ismail A, Tennakoon L, Spain DA, Mohseni S. Comparative Analysis of Frailty Scores for Predicting Adverse Outcomes in Hip Fracture Patients: Insights from the United States National Inpatient Sample. J Pers Med. 2024;14:621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13:818-829. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Karres J, Heesakkers NA, Ultee JM, Vrouenraets BC. Predicting 30-day mortality following hip fracture surgery: evaluation of six risk prediction models. Injury. 2015;46:371-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ringdal GI, Ringdal K, Juliebø V, Wyller TB, Hjermstad MJ, Loge JH. Using the Mini-Mental State Examination to screen for delirium in elderly patients with hip fracture. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2011;32:394-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Andrassy KM. Comments on 'KDIGO 2012 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease'. Kidney Int. 2013;84:622-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 289] [Cited by in RCA: 574] [Article Influence: 47.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Rushton PR, Reed MR, Pratt RK. Independent validation of the Nottingham Hip Fracture Score and identification of regional variation in patient risk within England. Bone Joint J. 2015;97-B:100-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tilkeridis K, Ververidis A, Kiziridis G, Kotzamitelos D, Galiatsatos D, Mavropoulos R, Rechova KV, Drosos G. Validity of Nottingham Hip Fracture Score in Different Health Systems and a New Modified Version Validated to the Greek Population. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:7665-7672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Fazal MA, Shah A, Mohamed FY, Hassan R. Postoperative haemoglobin estimation in elderly hip fractures. Aging Med (Milton). 2021;4:175-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zhang YM, Li K, Cao WW, Chen SH, Zhang BF. The Effect of Hematocrit on All-Cause Mortality in Geriatric Patients with Hip Fractures: A Prospective Cohort Study. J Clin Med. 2023;12:2010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Choi JY, Cho KJ, Kim SW, Yoon SJ, Kang MG, Kim KI, Lee YK, Koo KH, Kim CH. Prediction of Mortality and Postoperative Complications using the Hip-Multidimensional Frailty Score in Elderly Patients with Hip Fracture. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42966. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Dhingra M, Goyal T, Yadav A, Choudhury AK. One-year mortality rates and factors affecting mortality after surgery for fracture neck of femur in the elderly. J Midlife Health. 2021;12:276-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | García-Tercero E, Belenguer-Varea Á, Villalon-Ruibio D, López Gómez J, Trigo-Suarez R, Cunha-Pérez C, Borda MG, Tarazona-Santabalbina FJ. Respiratory Complications Are the Main Predictors of 1-Year Mortality in Patients with Hip Fractures: The Results from the Alzira Retrospective Cohort Study. Geriatrics (Basel). 2024;9:47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Seyedi HR, Mahdian M, Khosravi G, Bidgoli MS, Mousavi SG, Razavizadeh MR, Mahdian S, Mohammadzadeh M. Prediction of mortality in hip fracture patients: role of routine blood tests. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2015;3:51-55. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Arslan K, Celik S, Arslan HC, Sahin AS, Genc Y, Erturk C. Predictive value of prognostic nutritional index on postoperative intensive care requirement and mortality in geriatric hip fracture patients. North Clin Istanb. 2024;11:249-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | de Jong L, Mal Klem T, Kuijper TM, Roukema GR. Validation of the Nottingham Hip Fracture Score (NHFS) to predict 30-day mortality in patients with an intracapsular hip fracture. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2019;105:485-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Olsen F, Lundborg F, Kristiansson J, Hård Af Segerstad M, Ricksten SE, Nellgård B. Validation of the Nottingham Hip Fracture Score (NHFS) for the prediction of 30-day mortality in a Swedish cohort of hip fractures. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2021;65:1413-1420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | van Rijckevorsel VAJIM, Roukema GR, Klem TMAL, Kuijper TM, de Jong L; Dutch Hip Fracture Registry Collaboration. Validation of the Nottingham Hip Fracture Score (NHFS) in Patients with Hip Fracture: A Prospective Cohort Study in the Netherlands. Clin Interv Aging. 2021;16:1555-1562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Tian Y, Yao Y, Zhou J, Diao X, Chen H, Cai K, Ma X, Wang S. Dynamic APACHE II Score to Predict the Outcome of Intensive Care Unit Patients. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:744907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 28. | Chaves A, Dutra M, Geraldino G, Ghilardi M, Carrasco H, Carvalho S. Mortality in elderly patients with hip fractures: a retrospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2005;9:119. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Hannan EL, Magaziner J, Wang JJ, Eastwood EA, Silberzweig SB, Gilbert M, Morrison RS, McLaughlin MA, Orosz GM, Siu AL. Mortality and locomotion 6 months after hospitalization for hip fracture: risk factors and risk-adjusted hospital outcomes. JAMA. 2001;285:2736-2742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 319] [Cited by in RCA: 319] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/