Published online Mar 20, 2026. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v16.i1.109316

Revised: June 3, 2025

Accepted: August 25, 2025

Published online: March 20, 2026

Processing time: 279 Days and 9.8 Hours

In the United States, colorectal cancer is the third most prevalent non-skin cancer, causing 8% of cancer-related deaths. The most effective way to decrease cancer morbidity and mortality is cancer screening. However, individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ+) are less likely to utilize cancer screening services compared to the general population. To understand the barriers to effective colorectal cancer screening in the LGBTQ+ population and recommend solutions, we conducted a critical review of the lite

Core Tip: Colorectal cancer is the third most common non-skin cancer in the United States, yet lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ+) individuals are less likely to undergo screening, contributing to healthcare disparities. This critical literature minireview, covering studies up to March 2024, examines barriers to colorectal cancer screening in the LGBTQ+ population across patient, provider, institutional, and policy levels. Key challenges include social stigma, lack of provider awareness, and insufficient culturally competent care. Proposed solutions include provider training, enhancing screening access, and adopting patient-centered models. The review emphasizes the need for a holistic, multi-level approach to ensure equitable cancer screening and improved outcomes for LGBTQ+ individuals.

- Citation: Kalluru PKR, Valisekka SS, Katamreddy Y, Cherukuri A, Kuchi D, Siddenthi SM, Mandyam S. Addressing barriers and advancing equitable colorectal cancer screening in the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning population. World J Methodol 2026; 16(1): 109316

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v16/i1/109316.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v16.i1.109316

Colorectal cancer, the third most commonly diagnosed cancer globally, accounts for 11% of all cancer diagnoses[1]. However, colorectal cancer screening rates are suboptimal, particularly in marginalized groups such as the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ+) community. This leads to healthcare inequalities and disparities in cancer outcomes[2]. Studies have shown that LGBTQ+ individuals are less likely to undergo recommended screenings than their heterosexual counterparts, resulting in higher cancer incidence[3]. It is, therefore, crucial to comprehend the unique barriers impeding colorectal cancer screening among the LGBTQ+ population. A comprehensive literature review was conducted using multiple databases, employing search strings such as “colorectal cancer”, “screening”, “LGBTQ+”, “healthcare equity”, and “barriers”. All retrieved articles were assessed rigorously for relevance.

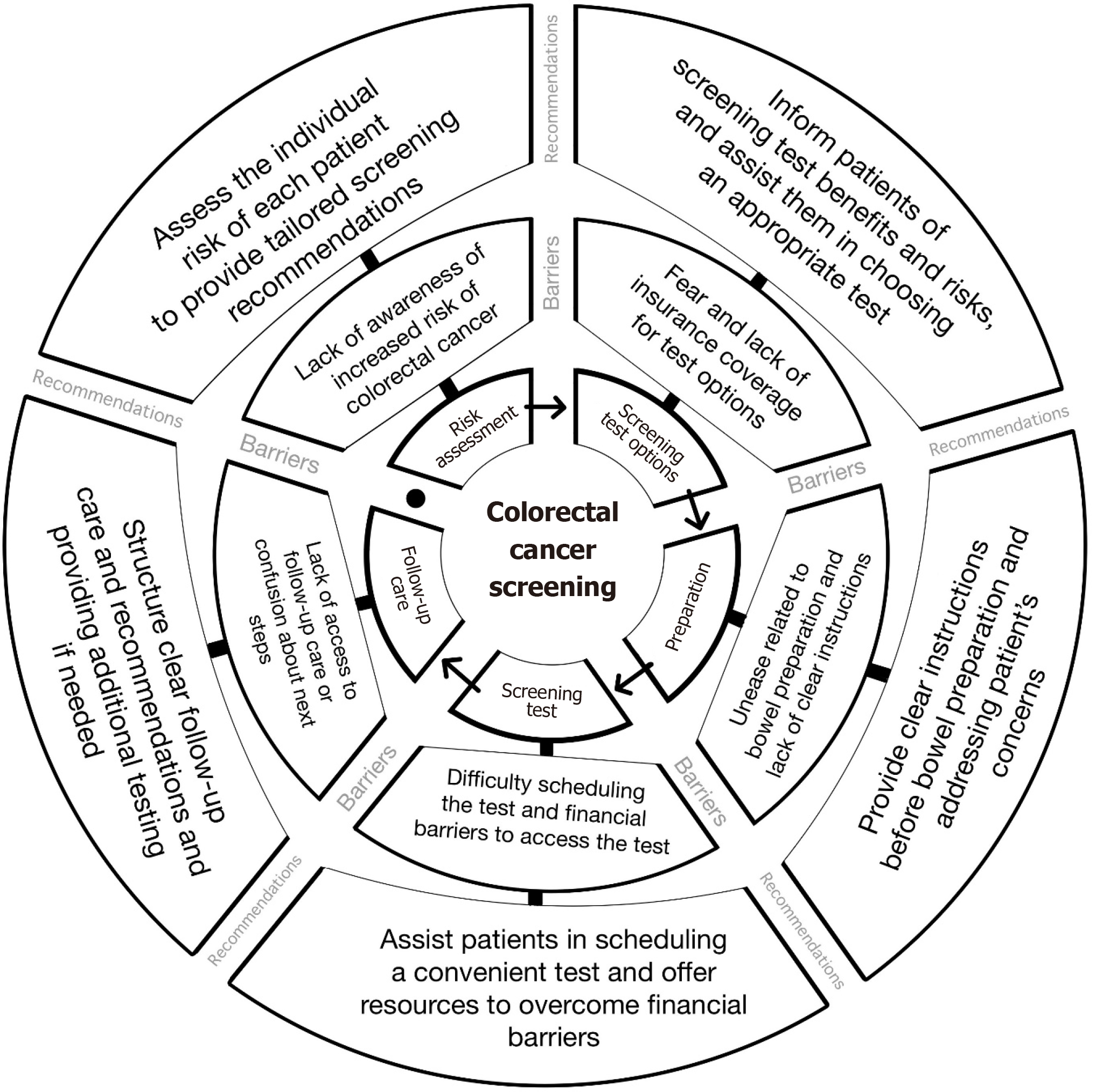

To reduce health disparities and improve cancer outcomes, it is imperative to enhance colorectal cancer screening rates in the LGBTQ+ community. Patients must be screened based on their risk factors, irrespective of their gender identity or sexual orientation. While research on cancer risk in the LGBTQ+ population is limited, recent studies suggest higher cancer incidence, diagnosis, prevalence, and mortality rates than the general population[4]. Understanding the barriers hindering colorectal cancer screening in the LGBTQ+ community is vital to achieving this objective. Figure 1 showcases the challenges that LGBTQ+ individuals could experience during different phases of colorectal cancer screening, along with proposed solutions.

Our study endeavors to recognize and explicate the hindrances that impede the LGBTQ+ community's access to colorectal cancer screening and suggest ways to increase screening rates. We scrutinize these obstacles and suggestions from multiple perspectives, encompassing patient, provider, and institutional levels. Moreover, we explore these barriers and recommendations concerning healthcare insurance, population surveys, and health policies. Through a thorough analysis of these challenges and recommendations, our research can provide insights for policy and practice alterations that can lessen health inequities and enhance cancer outcomes for the LGBTQ+ population.

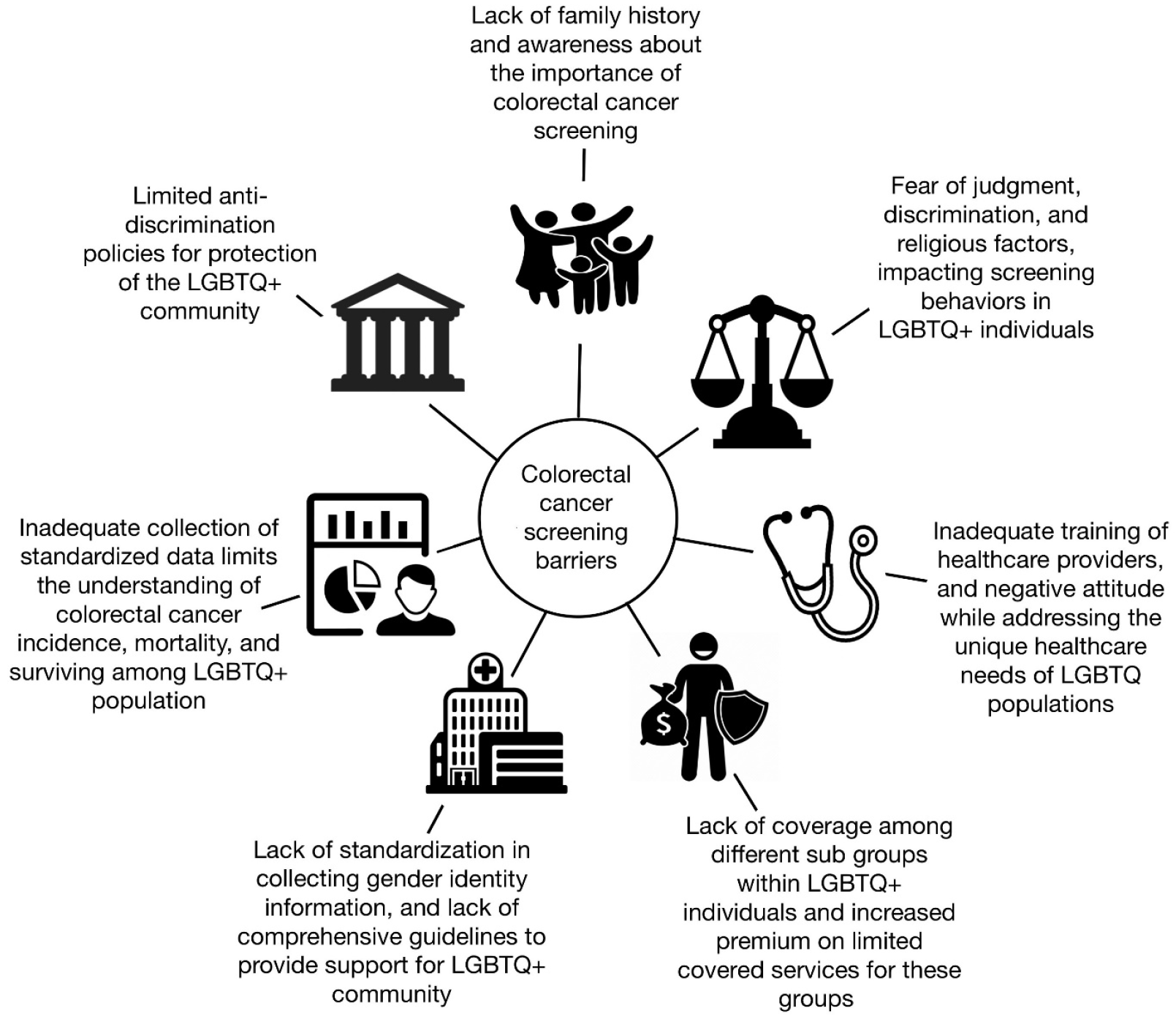

Figure 2 illustrates the obstacles that LGBTQ+ individuals might face before undergoing colorectal cancer screening.

Barriers: One significant barrier among LGBTQ+ individuals is the fear of judgment and discrimination due to their life choices or sexual preferences[5]. Previous experiences of mistreatment or discrimination can compound this fear, leading them to avoid disclosing their sexuality unless they feel safe and confident enough to do so. A lack of awareness about the importance of colorectal cancer screening can also lead to reduced motivation to undergo the colorectal cancer screening process. The fear of the colonoscopy procedure and a positive diagnosis can further deter individuals from participating in screening[6,7].

In addition, the LGBTQ+ community living in non-urban areas may face challenges accessing progressive healthcare services, which are not as readily available as they are for their urban counterparts[8]. Furthermore, individuals may feel more at ease in revealing their sexual orientation or gender identity when they have acquired complete professional licensure, indicating the possible impact of employment status on disclosing such personal information[9]. The expression of one's LGBTQ+ identity can also be impacted by various social identities that either confer advantages or disadvantages[9]. Poverty level also plays a role in the utilization of healthcare services, which can affect screening behaviors in the LGBTQ+ population and the general population[10]. Religious factors can also impact screening behaviors, with religious communities that hold negative views about LGBTQ+ individuals contributing to stigma, discrimination, and limited access to healthcare services[11].

For LGBTQ+ individuals, a lack of family history knowledge can hinder their ability to access genetic counseling and testing services for hereditary cancer risk assessment, leading to delayed screening or risk-reduction strategies[12]. Additionally, strained relationships with families may impact their communication about health issues[12]. After a cancer diagnosis, past rejection or lack of acceptance from biological families may cause LGBTQ+ individuals to rely less on them for support, leading to isolation during and after treatment. This may discourage them from seeking screening or early interventions[13,14].

Recommendations: Encouraging LGBTQ+ individuals to find healthcare providers who are knowledgeable about their unique needs and who provide culturally sensitive care to reduce the risk of health issues.

Raising awareness about the importance of colorectal cancer screening through public education campaigns to dispel myths and misconceptions that might prevent individuals from seeking screening[6,7].

Creating opportunities for the LGBTQ+ community to share their positive and non-judgmental screening experiences with peers to enhance participation in cancer screening programs[15].

Providing education and training to healthcare providers working in religiously affiliated healthcare settings and promoting acceptance and inclusion of LGBTQ+ individuals within religious communities to reduce stigma and improve access to healthcare services[11].

Utilizing telemedicine and at-home testing options increases screening access while reducing the need for in-person appointments, which can be difficult for some[16].

Family and social support can play a crucial role in promoting positive healthcare experiences and outcomes for LGBTQ+ individuals by providing advocacy, accompanying them to appointments, and helping to resolve discriminatory behavior[14].

Utilizing social media platforms to overcome barriers, expand or strengthen online communities, and encourage the expression of LGBTQ+ identity has been linked to various benefits for well-being[17].

Barriers: The inadequate training of healthcare providers in addressing the unique healthcare needs of LGBTQ+ individuals has resulted in disparities in healthcare access and quality for this population[5]. Lack of cultural competence leads to this population's discomfort and avoidance of healthcare, exacerbating healthcare disparities. Negative attitudes towards gender minorities among healthcare professionals can result in inadequate or inappropriate healthcare[2]. According to a published report, 20% of transgender and gender-diverse individuals have experienced denial of medical care owing to their gender identity, while an additional 6% have reported negative interactions with healthcare providers[18]. Implicit biases among healthcare professionals are also a concern, potentially impacting the quality of care provided to LGBTQ+ populations[19].

Recommendations: Alongside clinical expertise, it is equally important to have cultural competence when providing healthcare to LGBTQ+ people. This involves establishing an atmosphere where they can freely express their health concerns and stories without feeling uncomfortable, as well as refraining from using language that could be insensitive or discriminatory[2,20]. Studies have shown that many LGBTQ+ patients are willing to disclose their sexual orientation when asked, and by doing so, healthcare providers can tailor their treatment plans to their patient's needs and concerns[14]. Therefore, routine inquiry about sexual orientation should be a standard part of medical practice, ensuring that all patients receive the best possible care. Here are some recommendations to create a more welcoming and safer environment for LGBTQ+ patients: (1) Paying attention to the patient and following their lead, and if in doubt, asking how they or their partner should be addressed[21]; (2) Inquiring about each patient's preferred name and pronouns and using them consistently throughout the visit; (3) Providing LGBTQ+ inclusive health education materials that address their specific health concerns; and (4) Not revealing their sexual orientation or gender identity to anyone without explicit permission.

While these changes are a starting point, comprehensive cultural competence training is still required to provide quality care to LGBTQ+ patients[22]. Healthcare professionals must receive formal training to avoid misgendering and confusion during cancer screening appointments[23]. They can expand their knowledge and skills in LGBTQ+ cancer care by seeking education and training through online courses, conferences, and continuing education programs[5]. Providers can also play an important role in addressing colon cancer screening fears and misconceptions by explaining the screening process and the potential benefits of early detection. Additionally, funding for community organizations to provide peer-based training and support for clinicians is very much needed[24].

Barriers: The lack of standardization in collecting gender identity information across various healthcare institutions is a pressing issue. The National Academy of Medicine, formerly the Institute of Medicine, has called for electronic health records (EHR) to include gender identity information as a standard practice. Regrettably, most EHR systems do not currently store structured data on gender identity or sexual orientation, highlighting the urgent need for reform[21]. Additionally, there are no comprehensive guidelines to provide continuous support for the LGBTQ+ community throughout the care continuum, further underscoring the need for systemic changes[25]. Despite a few institutions having sexual health education programs akin to the High School FLASH, many lack comprehensive training, with participation from LGBTQ+ individuals, as tutors or inpatient panels being a crucial missing element in effective training programs[26].

Recommendations: It is imperative that institutions take steps to address these gaps in knowledge and training to provide quality care for the LGBTQ+ community. Here are some of the recommendations on an institutional level.

Using the registration forms and engaging in open dialogue with patients by institutions for collecting information about sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI). Collecting SOGI data in electronic medical record (EMR) is essential to understanding the healthcare needs of LGBTQ+ individuals better, as it has the potential to improve cancer screening adherence[27]. However, healthcare organizations must take appropriate measures to address privacy and confidentiality[2]. It is also recommended to include functionality in EMRs for ensuring accurate cross-checking of gender identity with the sex assigned at birth to minimize data interpretation errors[28].

Creating a welcoming environment for the LGBTQ+ community by advertising LGBTQ+ inclusive practices. Staff should be trained to use patients' chosen names and pronouns and employ members of the LGBTQ+ community as part of their staff. Extensive training programs should be provided for staff, including those in Registration, Environmental Services, and Food Services, covering topics such as Cultural Competency, Unconscious Bias, and Safe-Zone training to promote cultural awareness and learning[29].

Displaying LGBTQ+ symbols and posters featuring diverse transgender or same-sex couples can also be helpful. Healthcare organizations should commemorate LGBTQ+ Pride Day and National Transgender Day of Remembrance to show support for the LGBTQ+ community[30].

Establishing Diversity and Inclusion Workgroups that include LGBTQ+ representatives and modifying policies to prioritize respect and acceptance.

Barriers: Health insurance coverage can present a significant challenge to individuals seeking colorectal cancer screening, especially those at higher risk due to a history of colon polyps or inflammatory bowel disease. This challenge is com

Certain states face legal obstacles to implementing laws that forbid discrimination based on SOGI), which can hinder LGBTQ+ people from obtaining health insurance coverage. Such legal challenges make it difficult for them to receive essential healthcare services, including gender-affirming care, preventive care, and mental health services. Discriminatory actions can manifest in multiple ways, such as refusal of coverage, increased premiums, or limitations on covered service types.

Recommendations: Advocating insurance policies that cover screening tests and promoting awareness of available coverage options to the LGBTQ+ population can play a significant role in improving healthcare access for LGBTQ+ patients. However, transgender patients face limited health insurance coverage for appropriate and fair care compared to heterosexual patients. To address this issue, insurers can provide a link to the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association's physician database in their provider directory. This will allow LGBTQ+ patients to access care from healthcare providers with experience addressing their specific healthcare needs. In addition to facilitating access to LGBTQ+ friendly providers, insurers can promote healthcare equity for this population by ensuring that their facilities and provider directories are inclusive and welcoming[2].

Barriers: The United States currently has limited anti-discrimination protections for the LGBTQ+ community within the healthcare system, necessitating significant policy and practice changes to establish more robust safeguards[4]. Although awareness-raising initiatives have increased, targeted interventions for the LGBTQ+ population remain insufficient[24].

Recommendations: Anti-discrimination laws are crucial in achieving health equity for the LGBTQ+ population. They can guarantee access to healthcare for LGBTQ+ individuals without the risk of prejudice or unfair treatment[31]. Also, developing policies that provide comprehensive training and exposure to LGBTQ+ issues for future healthcare providers can increase the number of competent providers and improve access to cancer screening and treatment. To achieve this goal, the University of Washington School of Medicine has introduced an LGBTQ+ Health Pathway for medical students, offering extensive experience caring for LGBTQ+ patients[32].

Barriers: The inadequate collection of standardized data on SOGI in national surveys and registries creates obstacles in comprehending the experiences of LGBTQ+ individuals with cancer, which impacts our ability to determine if cancer health studies are inclusive of the knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and satisfaction of sexual and gender minorities[33]. This lack of comprehensive data also limits our understanding of cancer incidence, mortality, and survivorship among LGBTQ+ populations. When SOGI data are collected, inconsistent recordings may underestimate the prevalence of cancer among these communities, restricting the development of targeted interventions and prevention strategies.

Furthermore, the lack of organized monitoring of colorectal cancer among sexual or gender minorities is a significant knowledge gap[34]. Although sexual orientation data collection has gained prominence in state and federal health surveys, there is no systematic surveillance of colorectal cancer among these communities. This deficiency of data makes it challenging to design interventions and prevention strategies that meet their unique needs. Additionally, the lack of data complicates the evaluation of current screening and treatment programs' effectiveness in serving these populations.

Recommendations: Incorporating questions related to SOGI into their intake forms by healthcare providers and in research studies. This would provide crucial insight into the unique healthcare needs and experiences of sexual and gender minorities, which can be used to create targeted interventions and policies. However, collecting this information must be done with sensitivity, respect, and the option to decline or not answer. Creating a safe and supportive envi

Improving specific research infrastructure and funding methods for LGBTQ+ individuals is crucial for addressing health disparities in this population[36]. The lack of sufficient data on health outcomes among LGBTQ+ individuals is due to inadequate representation of SOGI in research studies, hindering healthcare providers and policymakers from making informed decisions about their health needs. Including SOGI questions in national surveys and databases and increasing funding for research focused on this population is critical for identifying gaps in care and disparities in health outcomes among LGBTQ+ individuals. This information can be used to develop public health programs and interventions that meet their needs[2].

Improving data collection practices by including social, demographic, and economic status information for LGBTQ+ individuals in cancer surveillance reports and the United States Census[32].

This review is predominantly based on studies conducted in the United States, and most of the referenced research is observational or descriptive in nature. As a result, the generalizability of the recommendations may be limited across different contexts and subgroups. Given the scarcity of clinical trials and the lack of intersectional and longitudinal research on this topic, we adopted a narrative rather than a systematic review approach. We recommend that future research address these gaps by incorporating more rigorous methodologies. In particular, we encourage the development of multicenter studies and research that explores the experiences of specific LGBTQ+ subgroups-such as transgender individuals, racial and ethnic minorities, and those living in rural or underserved areas-to enhance the broader applicability of findings.

Colorectal cancer screening rates are inadequate, especially among disadvantaged groups like the LGBTQ+ population, resulting in health disparities and inequities in cancer outcomes. Healthcare barriers for LGBTQ+ individuals exist at the individual, provider, and institutional levels, including fear of judgment, discrimination, and lack of awareness. Inadequate training, negative attitudes, implicit biases, and lack of cultural competence among healthcare providers also contribute to healthcare disparities. To address these barriers, culturally sensitive healthcare providers, public education campaigns, and cultural competence training are needed. Standardizing gender identity information collection and funding community organizations for peer-based training and support for clinicians can also improve healthcare access and quality. Attaining health equity in colorectal cancer screening and treatment for the LGBTQ+ community encounters major challenges, including insurance limitations, legal barriers, insufficient anti-discrimination measures, and incomplete SOGI data. To overcome these obstacles, proposed solutions include advocating for comprehensive insurance coverage and improving data collection practices through SOGI inquiries. In conclusion, addressing the barriers to colorectal cancer screening in the LGBTQ+ population requires a multifaceted approach involving healthcare providers, policymakers, and researchers, leading to improved health outcomes and equity for all. We also recommend that future research focus on pinpointing the precise challenges encountered by LGBTQ+ populations, thereby enhancing their colorectal cancer screening rates.

| 1. | Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53206] [Cited by in RCA: 56690] [Article Influence: 7086.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (135)] |

| 2. | Simon Rosser B, Merengwa E, Capistrant BD, Iantaffi A, Kilian G, Kohli N, Konety BR, Mitteldorf D, West W. Prostate Cancer in Gay, Bisexual, and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men: A Review. LGBT Health. 2016;3:32-41. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Silverberg MJ, Nash R, Becerra-Culqui TA, Cromwell L, Getahun D, Hunkeler E, Lash TL, Millman A, Quinn VP, Robinson B, Roblin D, Slovis J, Tangpricha V, Goodman M. Cohort study of cancer risk among insured transgender people. Ann Epidemiol. 2017;27:499-501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Olsen K. AACR conference examines cancer disparities in the LGBTQ population. United States: AACR Blog, 2021. |

| 6. | Meissner HI, Breen N, Klabunde CN, Vernon SW. Patterns of colorectal cancer screening uptake among men and women in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:389-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 416] [Cited by in RCA: 448] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Klabunde CN, Cronin KA, Breen N, Waldron WR, Ambs AH, Nadel MR. Trends in colorectal cancer test use among vulnerable populations in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:1611-1621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Macapagal K, Bhatia R, Greene GJ. Differences in Healthcare Access, Use, and Experiences Within a Community Sample of Racially Diverse Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Questioning Emerging Adults. LGBT Health. 2016;3:434-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 238] [Article Influence: 23.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Beagan BL, Sibbald KR, Bizzeth SR, Pride TM. Factors influencing LGBTQ+ disclosure decision-making by Canadian health professionals: A qualitative study. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0280558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Boehmer U, Ozonoff A, Miao X. An ecological analysis of colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: differences by sexual orientation. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Westwood S. Religious-based negative attitudes towards LGBTQ people among healthcare, social care and social work students and professionals: A review of the international literature. Health Soc Care Community. 2022;30:e1449-e1470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Rolf BA, Schneider JL, Amendola LM, Davis JV, Mittendorf KF, Schmidt MA, Jarvik GP, Wilfond BS, Goddard KAB, Ezzell Hunter J. Barriers to family history knowledge and family communication among LGBTQ+ individuals in the context of hereditary cancer risk assessment. J Genet Couns. 2022;31:230-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kamen CS, Smith-Stoner M, Heckler CE, Flannery M, Margolies L. Social support, self-rated health, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender identity disclosure to cancer care providers. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2015;42:44-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Baughman A, Clark MA, Boehmer U. Experiences and Concerns of Lesbian, Gay, or Bisexual Survivors of Colorectal Cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2017;44:350-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Pelters P, Hertting K, Kostenius C, Lindgren EC. "This Group is Like a Home to Me:" understandings of health of LGBTQ refugees in a Swedish health-related integration intervention: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2022;22:1246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gorin SNS, Jimbo M, Heizelman R, Harmes KM, Harper DM. The future of cancer screening after COVID-19 may be at home. Cancer. 2021;127:498-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Berger MN, Taba M, Marino JL, Lim MSC, Skinner SR. Social Media Use and Health and Well-being of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Youth: Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24:e38449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Stroumsa D, Wu JP. Welcoming transgender and nonbinary patients: expanding the language of "women's health". Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219:585.e1-585.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Morris M, Cooper RL, Ramesh A, Tabatabai M, Arcury TA, Shinn M, Im W, Juarez P, Matthews-Juarez P. Training to reduce LGBTQ-related bias among medical, nursing, and dental students and providers: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19:325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 30.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Serrano M, Metz J, Fernandez A, Mendelson E, Alvarado G, Munoz M, Reyes E, Quintanilla R, Pelayo D, Surani Z. Abstract C092: Understanding the cancer needs of LGBTQ Latinx communities. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2020;29:C092-C092. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ehrenfeld JM, Gottlieb KG, Beach LB, Monahan SE, Fabbri D. Development of a Natural Language Processing Algorithm to Identify and Evaluate Transgender Patients in Electronic Health Record Systems. Ethn Dis. 2019;29:441-450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Margolies L, Brown CG. Increasing cultural competence with LGBTQ patients. Nursing. 2019;49:34-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lombardo J, Ko K, Shimada A, Nelson N, Wright C, Chen J, Maity A, Ruggiero ML, Richard S, Papanagnou D, Mitchell E, Leader A, Simone NL. Perceptions of and barriers to cancer screening by the sexual and gender minority community: a glimpse into the health care disparity. Cancer Causes Control. 2022;33:559-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Drysdale K, Cama E, Botfield J, Bear B, Cerio R, Newman CE. Targeting cancer prevention and screening interventions to LGBTQ communities: A scoping review. Health Soc Care Community. 2021;29:1233-1248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Dunne W, Adebayo N, Danner S, Post S, O'Brian C, Tom L, Osei C, Blum C, Rivera J, Molina E, Trosman J, Weldon C, Ekong A, Adetoro E, Rapkin B, Simon MA. A Learning Health System Approach to Cancer Survivorship Care Among LGBTQ+ Communities. JCO Oncol Pract. 2023;19:e103-e114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kesler K, Gerber A, Laris BA, Anderson P, Baumler E, Coyle K. High School FLASH Sexual Health Education Curriculum: LGBTQ Inclusivity Strategies Reduce Homophobia and Transphobia. Prev Sci. 2023;24:272-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Charkhchi P, Schabath MB, Carlos RC. Modifiers of Cancer Screening Prevention Among Sexual and Gender Minorities in the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019;16:607-620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Grasso C, Goldhammer H, Brown RJ, Furness BW. Using sexual orientation and gender identity data in electronic health records to assess for disparities in preventive health screening services. Int J Med Inform. 2020;142:104245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Marney HL, Vawdrey DK, Warsame L, Tavares S, Shapiro A, Breese A, Brayford A, Chittalia AZ. Overcoming technical and cultural challenges to delivering equitable care for LGBTQ+ individuals in a rural, underserved area. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2022;29:372-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Tuller D. For LGBTQ Patients, High-Quality Care In A Welcoming Environment. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39:736-739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Eschliman EL, Adames CN, Rosen JD. Antidiscrimination Laws as Essential Tools for Achieving LGBTQ+ Health Equity. JAMA. 2023;329:793-794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Gibson AW, Radix AE, Maingi S, Patel S. Cancer care in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer populations. Future Oncol. 2017;13:1333-1344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | National Cancer Institute. Cancer health disparities [Internet]. Bethesda: National Cancer Institute, 2020. [cited 2025 June 02]. Available from: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/understanding/disparities. |

| 34. | Sandoval G, Obstein KL. Tu1116 disparities in health: Lower colorectal cancer screening rates among lgbtq patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;91:AB552. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 35. | Understanding the Well-Being of LGBTQI+ Populations. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2020-Oct-21. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Safer JD. Research gaps in medical treatment of transgender/nonbinary people. J Clin Invest. 2021;131:e142029. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/