Published online Mar 20, 2026. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v16.i1.107426

Revised: April 28, 2025

Accepted: June 19, 2025

Published online: March 20, 2026

Processing time: 324 Days and 15.9 Hours

The sinonasal area poses diagnostic challenges due to a range of benign and malignant tumors presenting with vague symptoms. Conventional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has limited specificity in differentiation.

To study the role of dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (DCE-MRI), intravoxel in

This prospective study was conducted at a tertiary center in which 30 patients with sinonasal masses (18 malignant lesions and 12 benign lesions) underwent routine MRI, conventional DWI and IVIM, and DCE-MRI. Various imaging para

Malignant lesions exhibited significantly lower apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC), true diffusion coefficient (Dt), and apparent diffusion coefficient (Dapp) values (P = 0.000, P = 0.015, and P = 0.030, respectively) and higher apparent kurtosis coefficient (Kapp) values (P = 0.001) than benign lesions. There were no significant differences in the pseudodiffusion coefficient, perfusion fraction, or perfusion parameters. Among all of the significant parameters, the ADC had the highest area under the curve (0.898). An ADC cutoff value of 1.57 × 10-3 mm2/second had a sen

This study highlights the utility of conventional DWI, DKI, and IVIM as noninvasive methods for distinguishing between benign and malignant sinonasal lesions; however, there is no added advantage of DKI and IVIM over conventional DWI. Similarly, the perfusion parameters also did not show an additive role in distinguishing between benign and malignant sinonasal lesions.

Core Tip: We studied the role of advanced magnetic resonance imaging techniques in the evaluation of sinonasal masses. The mean apparent diffusion coefficient derived from conventional diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) can serve as an imaging marker to differentiate between benign and malignant sinonasal masses. Other imaging parameters such as the true diffusion coefficient from intravoxel incoherent motion imaging (IVIM), kurtosis coefficient, and diffusion coefficient from diffusion kurtosis imaging (DKI) were also statistically significant. However, there was no incremental benefit of DKI and IVIM over conventional DWI. Perfusion parameters also did not show any significant difference.

- Citation: Saini M, Manchanda S, Bhalla AS, Kandasamy D, Kakkar A, Thakar A. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging in differentiating benign and malignant sinonasal masses: A prospective study and literature review. World J Methodol 2026; 16(1): 107426

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v16/i1/107426.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v16.i1.107426

The sinonasal area, which includes the nasal cavity and bilateral paranasal sinuses (maxillary, ethmoid, frontal and sphenoid sinus), is affected by a variety of benign and malignant lesions[1]. Most of these lesions present with nonspecific symptoms such as nasal obstruction, nasal discharge/epistaxis, proptosis, and neurological symptoms. These symptoms are similar for both neoplastic and inflammatory conditions. The role of imaging in the sinonasal area is to differentiate the inflammatory etiology from non- inflammatory etiology and further characterize them into benign and malignant. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are the primary imaging modalities of choice for evaluating sinonasal masses. CT provides excellent bony details while MRI offers superior soft tissue resolution. On CT, most of these lesions, whether neoplastic or non-neoplastic, present as soft tissue opacification of the sinonasal area with or without bony changes. Bony erosions/destruction and infiltrative/destructive pattern of soft tissue are indicators suggestive of the malignant nature of the lesion. Conventional MRI (T1-weighted and T2-weighted) has limited spe

The role of conventional diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) has been described in the literature for differentiating benign and malignant sinonasal masses. Conventional DWI is based on the principle that the movements of water molecules are random (Gaussian diffusion)[2]. Conventional DW images are acquired at two or three b-values (usually at less than 1000), and it is assumed that a decrease in DWI signal is monoexponential as the b-value increases; however, this assumption does not hold true at lower b-values.

Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) derived from conventional DWI largely measures the extracellular space assuming Gaussian diffusion of water molecules; however, at the microscopic level, water diffusion is influenced by extracellular vessels, ducts, extracellular space tortuosity, cell size, cell density, cell arrangements, and extracellular space viscosity[3]. All of these factors lead to non-random/non-Gaussian water diffusion, and diffusion kurtosis imaging (DKI) is one of the methods used to quantify this. In DKI, images are acquired at higher b-values (greater than 1000). This model allows calculation of the apparent diffusion coefficient (Dapp) and kurtosis coefficient (Kapp). Dapp represents ADC values corrected for non-Gaussian water diffusion, and Kapp quantifies the deviation of the water diffusion from Gaussian diffusion[3]. The role of DKI has been described in gliomas, prostate, liver, and breast pathologies[4-7]. In this article, we explore its role in differentiating benign and malignant sinonasal masses.

Intravoxel incoherent motion imaging (IVIM) is another novel technique, first proposed by Le Bihan[8], that provides information about tissue diffusivity and microvascular perfusion without the need for contrast media. This model can separate the molecular diffusion and microcapillary perfusion by acquiring the data at low b-values and using biexponential method for analysis[8]. It allows calculation of the true diffusion coefficient (Dt), pseudodiffusion coefficient (Dx), and perfusion fraction (f). Dt provides information about the true water diffusion, Dx reflects the diffusivity of blood flowing in the capillary, and f represents the vascular volume fraction[8]. The role of IVIM has been described in tumor differentiation and characterization in breast and prostate, cancers hepatocellular carcinoma, and renal masses and in treatment response assessment[9-12].

Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (DCE-MRI) is a noninvasive technique used to quantify the tissue perfusion and permeability[13]. Both semiquantitative and quantitative perfusion parameters can be derived from DCE-MRI. In the head and neck region, DCE MRI has been evaluated for characterization of skull base[14] and salivary glands masses[15].

Because there are limited studies on the role of DCE-MRI, IVIM, and DKI in imaging sinonasal masses imaging, our study explored the utility of these novel yet potentially valuable imaging techniques as a game changer to the clinical workup of sinonasal masses in future.

A prospective cross-sectional study was conducted between September 2021 and February 2023 on 36 patients with sinonasal and nasopharyngeal masses, who were referred to our department for MRI. Approval from the institutional review board was obtained (No. IECPG-487/25.08.2021), and written informed consent was provided by every participant. Exclusion criteria included patients with sinonasal masses with a prior history of chemotherapy or radiation, previous surgery, those requiring general anesthesia for the MRI acquisition, and cases with imaging features typical of juvenile nasal angiofibroma. Of the initially enrolled 36 patients, 6 were excluded from the final analysis (5 patients lacked a final histopathology report and 1 lesion turned out be to enlarged adenoid on histology). The current study focused on the role of DCE-MRI, conventional DWI, IVIM, and DKI in the differentiation of sinonasal masses.

All MRI examinations were performed on the 3T MRI scanner (Ingenia; Philips Healthcare, Andover, MA, United States) using a 16-channel neurovascular coil in supine position. Routine diagnostic MRI sequences for the sinonasal area were performed. These included axial, coronal, and sagittal multipoint DIXON fat-suppressed T2WI and axial multipoint DIXON fat-suppressed T1WI. Single-shot turbo spin-echo (turbo spin factor: 43) axial conventional DWI sequences were obtained by applying diffusion gradients in three orthogonal planes for each slice, with three diffusion weightings (b-values of 0, 500, and 1000 seconds/mm2 and imaging parameters were: Time of repetition (TR)/time of echo (TE) 900-1100 milliseconds/70 milliseconds, slice thickness (4 mm), flip angle (90 degree), number of signal averages (3) and field of view (FOV) (190 × 190). For IVIM and DKI, acquisition was performed before giving contrast, over extended nine b-values and the imaging parameters were: TR/TE 3500 milliseconds/88 milliseconds, slice thickness (3 mm), flip angle (90 degree), number of signal averages (2), FOV (240 × 240) and nine b-factors: 0, 35, 50, 100, 175, 300, 500, 1500, and 2000 seconds/mm2. Total acquisition time was 12 minutes 15 seconds for both the IVIM and DKI sequences.

For DCE-MRI, multiphase three-dimensional (3D) T1WI fat-suppressed fast spoiled gradient recalled sequence was acquired, during which images were acquired during the course of administration of 0.1 mmol of gadoterate meglumine (Dotarem) per kilogram of patient body weight dose at 3 mL/second followed by saline flush. A total of 60 dynamic scans were performed, each with a temporal resolution of 4.3 seconds and after six baseline dynamic scans, contrast was injected. Following dynamic image acquisition, axial and 3D-T1WI postcontrast imaging were acquired.

For conventional DWI evaluation, freehand regions of interest (ROIs) were drawn manually on the lesions using ADC maps to obtain the representative ADC values. Evaluation of IVIM and DKI parameters was done using a dedicated PACS workstation (Intellispace Portal version 8.0; Philips Healthcare). Three freehand ROIs were drawn on the lesions (on different slices), each with a minimum area of more than 10 mm2. Similar ROIs were used to calculate the IVIM and DKI parameters.

Perfusion data from DCEMRI were analyzed for time-intensity curves (TICs), semiquantitative and quantitative parameters using the same PACS workstation (Intellispace Portal version 8.0; Philips). Three ROIs were drawn on enhancing tumor component (on different slices). The TIC was interpreted as progressive enhancement (type 1), plateau (type 2), and washout (type 3).

One radiologist (Smita Manchanda with 12 years of experience in head and neck imaging) drew freehand ROIs on the lesions.

The mean of three ROIs was taken for final analysis of all of the parameters. Areas of hemorrhage, necrosis, and cystic changes were avoided after correlating with T1W, T2W, and post contrast T1W images during ROI placement.

A composite gold standard was used as reference that included pathological analysis in 29 patients (96.67%), either from surgical specimen histopathology or core needle biopsy. In 1 patient (3.33%) who was a known case of thyroid carcinoma, imaging revealed an expansile lesion in the sphenoid sinus, which was considered metastasis. Based on this composite gold standard, 12 lesions were classified as benign and 18 lesions as malignant (Table 1).

| Groups | Diagnosis | Number of lesions |

| Benign (n = 12) | Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor | 1 |

| Mycetoma | 1 | |

| Central giant cell reparative granuloma | 1 | |

| Schwannoma | 1 | |

| Meningioma | 2 | |

| Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma | 1 | |

| Neuroendocrine tumor | 1 | |

| Solitary fibrous tumor | 1 | |

| Inflammatory nasal polyp | 3 | |

| Malignant (n = 18) | Squamous cell carcinoma | 4 |

| Undifferentiated Sinonasal carcinoma | 3 | |

| Sinonasal teratocarcinoma | 1 | |

| Lymphoma | 2 | |

| Plasmacytoma | 2 | |

| Chondrosarcoma | 1 | |

| Chondroma | 1 | |

| Nasopharyngeal carcinoma | 2 | |

| Nasopharyngeal adenocystic carcinoma | 1 | |

| Metastasis | 1 |

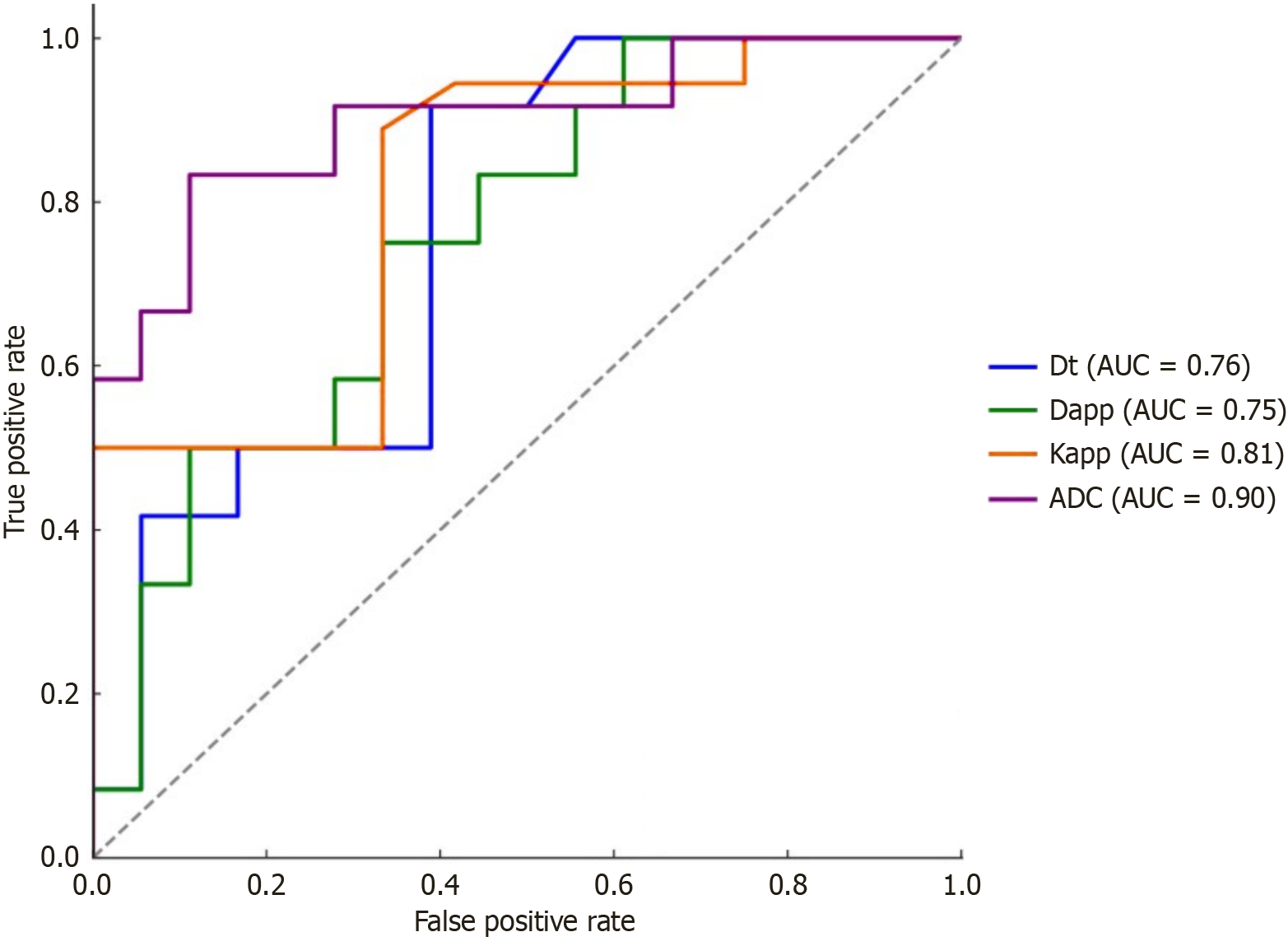

All of the statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 17 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, United States). After assessing the normality of the evaluated parameters, the Mann-Whitney test and independent samples t-test were used to compare continuous variables. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The area under the curve (AUC) for statistically significant parameters from conventional DWI, IVIM, and DKI was calculated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. Cutoff values with good sensitivity and specificity were derived from the ROC curves and corresponding graphs. Based on the ROC curves, the value with best sensitivity and specificity was selected as the cutoff value. Additionally, various combinations of statistically significant parameters from conventional DWI, IVIM, and DKI were evaluated to assess their predictive performance.

Among the 30 patients included in the analysis, 18 (60%) had malignant lesions and 12 (40%) had benign lesions (Table 1). The mean age of patients with benign lesions was 34.41 years (range 10-66 years), whereas those with malignant lesions had a higher mean age of 46.6 years (range 7-76 years), which showed borderline statistical significance (P = 0.07). There were 19 male patients (mean age: 44.5 years) and 11 female patients (mean age: 38.90 years). The most common location of the lesion was maxillary sinus (40%) followed by the nasopharynx (23.33%), sphenoid sinus (23.33%), ethmoid sinus (10%), and nasal cavity (3.33%).

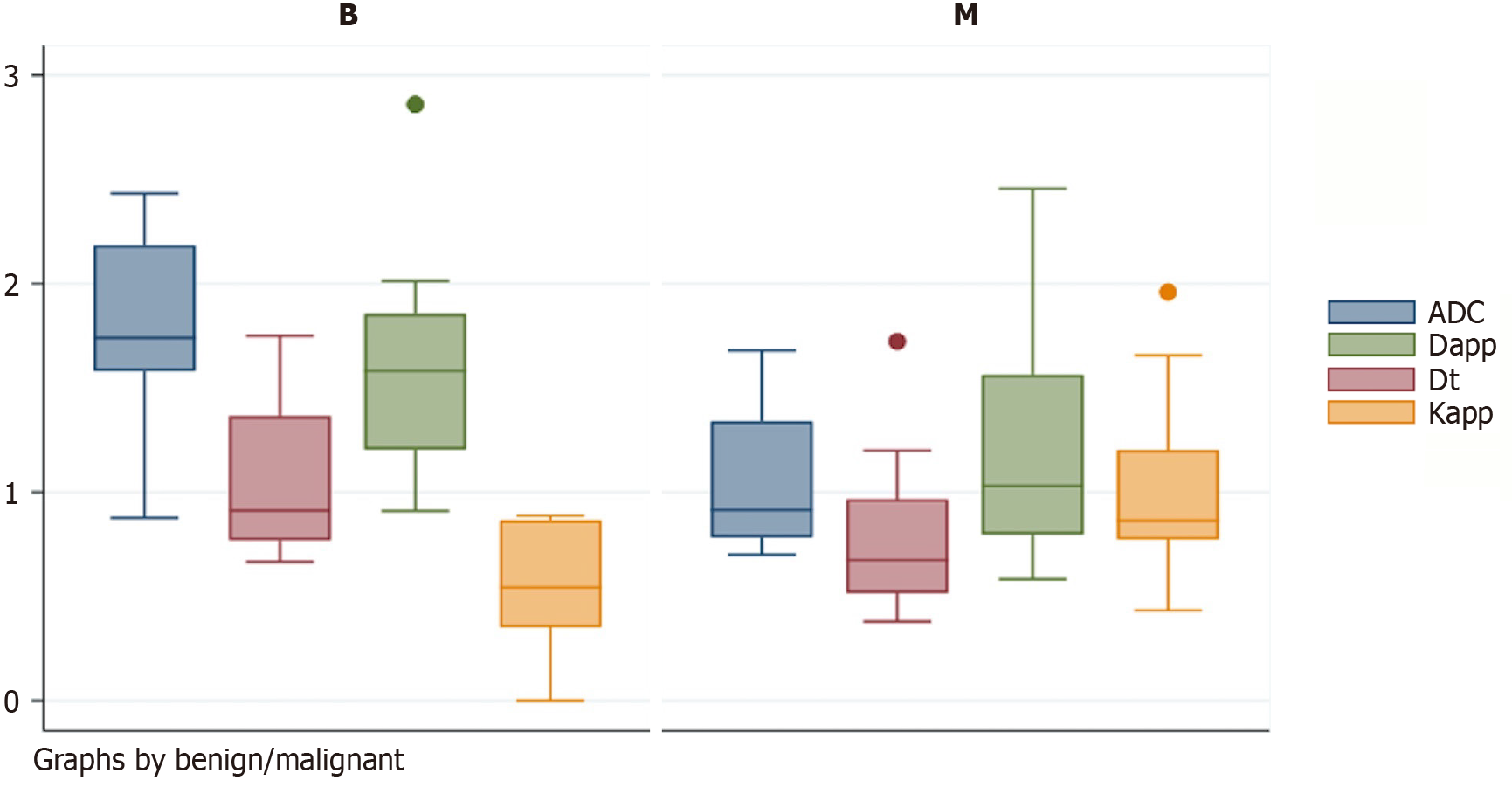

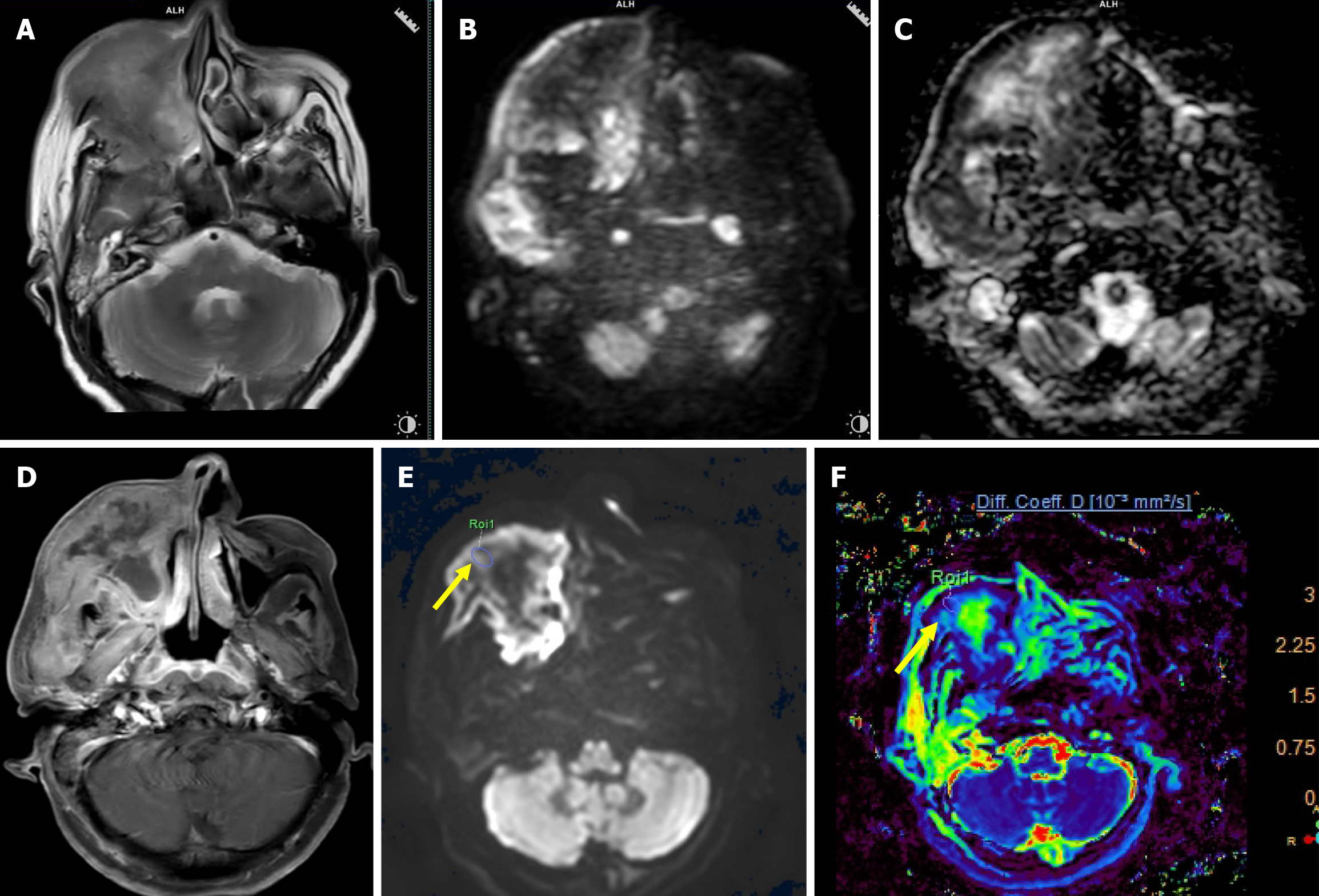

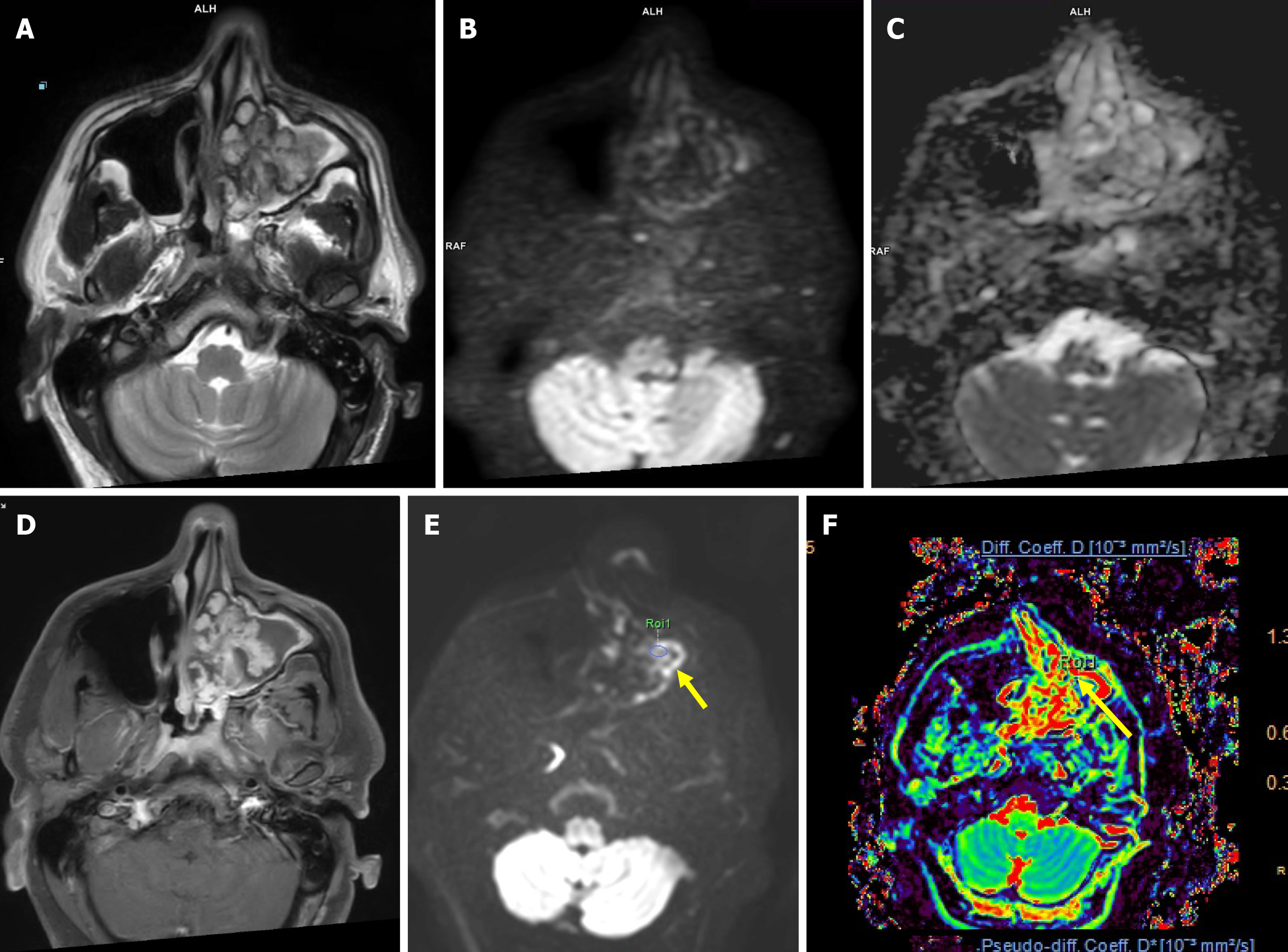

Malignant lesions demonstrated significantly lower ADC values compared to benign lesions, with a highly significant P = 0.000 (Figure 1 and Table 2). A cutoff value of 1.57 × 10-3 mm2/second derived from ROC curve analysis (Figure 2) had a sensitivity of 88.89%, specificity of 83.33%, and accuracy of 86.11% with AUC = 0.898 to predict a malignant lesion (Table 3). The graphical representation of the conventional DWI is illustrated in Figure 3A-D and Figure 4A-D.

| Parameters | Benign lesion | Malignant lesion | P value |

| ADC (× 10-3 mm2/second) | 1.77 ± 0.45 | 1.06 ± 0.32 | 0.000 |

| Dt (× 10-3 mm2/second) | 1.07 ± 0.38 | 0.76 ± 0.33 | 0.015 |

| Dx (× 10-3 mm2/second) | 30.49 ± 56.15 | 11.86 ± 16.82 | 0.109 |

| f | 0.23 ± 0.09 | 0.17 ± 0.07 | 0.070 |

| Dapp (× 10-3 mm2/second) | 1.59 ± 0.54 | 1.15 ± 0.50 | 0.030 |

| Kapp | 0.53 ± 0.32 | 1.01 ± 0.39 | 0.001 |

| Parameters | AUC | Cutoff value | Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy |

| ADC | 0.898 | 1.75 | 88.89% | 83.33% | 86.11% |

| Dt | 0.761 | 1.006 | 83.33% | 50% | 66.67% |

| Dapp | 0.755 | 1.35 | 66.67% | 66.67% | 66.67% |

| Kapp | 0.808 | 0.63 | 88.89% | 66.67% | 77.78% |

The malignant lesions had a significantly lower mean Dt value compared to benign lesions with a P = 0.015 (Figure 1 and Table 2). A Dt cutoff value of 1.006 × 10-3 mm2/second had a sensitivity of 83.33%, specificity of 50%, accuracy of 66.66%, and AUC = 0.761 to predict malignancy (Table 3). The graphical representation of mean Dt is illustrated in Figure 3E and F and Figure 4E and F for malignant and benign lesions, respectively.

The Dx and f did not show statistically significant differences between benign and malignant sinonasal lesions (Table 2).

The mean Dapp was significantly higher in benign lesions compared to malignant lesions with P = 0.030 (Figure 1 and Table 2). A Dapp cutoff value of 1.35 × 10-3 mm2/second had a sensitivity of 66.67%, specificity of 66.67%, and accuracy of 66.67% with AUC of 0.754 to predict malignancy (Table 3).

Another DKI parameter, mean Kapp, was significantly lower in benign lesions compared to malignant lesions with a

There was no significant difference found in types of TIC, semiquantitative and quantitative perfusion parameters for differentiating benign and malignant sinonasal masses.

Among all of these significant diffusion-related parameters, the ADC value had the highest diagnostic performance followed by Kapp.

A comparative analysis was also performed between the ROC curves of various significant parameters. A statistically significant difference was observed between the ROC curves of Dt and Dapp. However, no significant differences were noted among the ROC curves of the other parameters, as detailed in Table 4.

| Test result pair | AUC difference | P value |

| ADC-Dapp | 0.144 | 0.07 |

| ADC-Dt | 0.137 | 0.08 |

| ADC-Kapp | 0.090 | 0.09 |

| Kapp-Dapp | 0.053 | 0.08 |

| Kapp-Dt | 0.046 | 0.05 |

| Dt-Dapp | 0.007 | 0.04 |

A literature search on the role of ADC in differentiating benign from malignant sinonasal masses was conducted using PubMed and Google Scholar. Studies with full-text availability were included and are summarized in Table 5. Key parameters, such as sample size, number of b-values, ADC cutoff, and the mean ADC values for benign and malignant lesions were recorded. These studies proposed various ADC cutoff values for differentiating between benign and malignant sinonasal masses. The variation in ADC cutoff values across studies can be attributed to multiple technical and methodological factors. ADC value is influenced by the b-value, number of b-values, and various acquisition parameters. Both very low and very high b-values can lead to underestimation of the ADC value—low b-values due to perfusion effects and high b-values due to signal loss.

| Ref. | Number of lesions | Magnet strength and b-values | Cutoff value if given | Efficacy |

| Srinivasan et al[16] | 33 sinonasal masses (B-17 and M-16) | 3 T, b-values (0 and 800) | ADC-1.3 × 10-3 mm2/second | NA |

| Razek et al[23] | 50 sinonasal masses (B-12 and M-38) | 1.5 T, b-values (0, 500 and 1000) | ADC-1.53 × 10-3 mm2/second | Sn: 94.1%; Sp: 92% |

| Wang et al[17] | 197 sinonasal masses (B-81 and M-116) | 3 T, b-values (0, 700 and 1000) | ADCws (b value 0 and 1000)-1.37 × 10-3 mm2/second | Sn: 85.3%; Sp: 81.2% |

| El-Gerby et al[18] | 24 sinonasal masses (B-17 and M-7) | 1.5 T, b-values (500 and 1000) | ADC-1.2 × 10-3 mm2/second | Sn: 100%; Sp: 86.4% |

| Das et al[22] | 28 sinonasal masses (B-10 and M- 18) | 3 T, b-values (0, 500 and 1000) | ADC-1.79 × 10-3 mm2/second | Sn: 80%; Sp: 83.3% |

| Wang et al[19] | 98 sinonasal masses (B-40 and M- 58) | 3 T, b-values (0 and 1000) | ADC-0.852 × 10-3 mm2/second | Sn: 77.3%; Sp: 94.7% |

| Daga et al[20] | 40 sinonasal masses (B-17 and M-23) | 3 T, b-values (50 and 1000) | ADC-1.005 × 10-3 mm2/second | Accuracy: 92.5% |

| Xiao et al[30] | 131 sinonasal masses (B-56 and M-75) | 3 T, b-values (0 and 1000) | ADC-0.919 × 10-3mm2/second | Sn: 80%; Sp: 54.7% |

| 11 b-values for IVIM | Dt-0.715 × 10-3 mm2/second | Sn: 84.1%; Sp: 81.6% | ||

| f (%) 16.99 | Sn: 72.3%; Sp: 47.2% | |||

| Jiang et al[31] | 73 sinonasal masses (B-42 and M-31) | 3 T, 13 b-values | Dt-0.84 × 10-3 mm2/second | Sn: 74.16%; Sp: 73.81% |

| f (%) 27.1 | Sn: 61.27%; Sp: 90.50% | |||

| Jiang et al[26] | 81 sinonasal masses (B-35 and M-46) | 3 T, b-values (0 and 1000) | ADC-1.27 × 10-3 mm2/second | Sn: 69.6%; Sp: 77.1% |

| 13 b-values for DKI | Dapp-1.75 × 10-3 mm2/second | Sn: 82.6%; Sp: 77.1% | ||

| Kapp: 0.63 | Sn: 95.7%; Sp: 77.1% | |||

| Wang et al[21] | 72 sinonasal masses (B-38 and M-34) | 3 T, b-values (0, 1000) | ADC-1.01 × 10-3 mm2/second | |

| Our study (2023) | 30 sinonasal masses (B-12 and M-18) | 3 T, b-values (0, 500 and 1000) | ADC-1.57 × 10-3 mm2/second | Sn: 88.89%; Sp: 83.33% |

| 9 b-values for IVIM/DKI | Dt-0.97 × 10-3 mm2/second | Sn: 77.78%; Sp: 50.0% | ||

| Dapp-1.35 × 10-3 mm2/second | Sn: 66.67%; Sp: 66.67% | |||

| Kapp: 0.63 | Sn: 88.89%; Sp: 66.67% |

Our study assessed the diagnostic utility of DCE-MRI, conventional DWI, IVIM and DKI in differentiating between benign and malignant sinonasal masses. Among these, the absolute mean ADC value was significantly higher in the benign group compared to the malignant group. This finding aligns well with previously published literature (Table 5). The observed difference in ADC values likely reflects underlying histopathological differences between benign and malignant lesions. The malignant lesions are characterized by enlarged nuclei, hyperchromatism, and hypercellularity. This leads to reduced extracellular matrix and increased intracellular dimensions leading to a decrease in ADC[2].

Table 5 provides a comparative summary of prior studies that evaluated the use of ADC values in predicting malignancy within the sinonasal region[16-21].

Das et al[22] utilized imaging parameters similar to those in our study but reported a higher cutoff value (1.791 × 10-3 mm2/second). This discrepancy can be explained by a higher proportion of cases of juvenile nasal angiofibroma (25% of cases) in their study with a mean ADC value of 2.169 × 10-3 mm2/second.

Razek et al[23] also proposed a similar cutoff, but the authors found that benign tumor-like fibroma can show low ADC secondary to excess fibrous tissue[24] and malignant tumor-like adenoid cystic carcinoma can show higher ADC value secondary to prominent myxoid stroma[25]. In our study, one case of adenoid cystic carcinoma also showed a higher ADC value.

Jiang et al[26] also found that ADC analysis was promising to distinguish malignant from benign sinonasal lesions, but the authors proposed a lower cutoff which can be secondary to difference in acquisition parameters (b-values).

In our study, meningioma was the only benign lesion that had a lower ADC value. This finding can be explained by histological features of meningioma as it is an inherently hypercellular tumor, which will restrict the water diffusion leading to lower ADC. In the malignant group four lesions (chondrosarcoma, chordoma, nasopharyngeal adenoid cystic carcinoma and metastasis from papillary thyroid carcinoma) had higher ADC values. The higher ADC values of chondrosarcomas can be explained by varying degrees of cellularity within a cartilaginous stroma causing relatively free extracellular water motion[27]. Chordoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma consist of myxoid stroma which can lead to higher ADC value[25,27]. A high ADC value in a metastasis from papillary thyroid carcinoma can be explained by their fibrovascular core on histopathology which will facilitate the water diffusion[28]. Linh et al[29] also showed higher ADC values in malignant thyroid nodules.

Among the IVIM parameters, only Dt showed a statistically significant difference in differentiating benign and malignant sinonasal mass with significantly lower value in malignant group as compared to benign group and a cutoff value of 0.97 × 10-3 mm2/second had a sensitivity of 77.78%, specificity of 50.0%, and accuracy of 63.73% to declare malignant lesions. The lower Dt value in the malignant group corresponded with enlarged nuclei, hyperchromatism and hypercellularity of malignant lesions. Our results were consistent with the studies by Xiao et al[30] and Jiang et al[31], which also found lower Dt values in malignant lesions and proposed a cutoff values of 0.715 × 10-3 mm2/second and 0.84 × 10-3 mm2/second, respectively. We did not find any significant difference in Dx and f, likely due to the small sample size with marked histological heterogeneity in the lesions. A study conducted by Jiang et al[31] showed higher f in the benign compared to malignant lesions, and heterogeneous pathologies was given as one of the possible explanations for this finding.

Both DKI parameters showed a significant difference in differentiating benign and malignant sinonasal masses. The Dapp was significantly lower in malignant lesions compared to benign lesions and a cutoff value of 1.35 ×

The Kapp had a significantly higher mean value in malignant group as compared to benign group and a cutoff of 0.63 had a sensitivity of 95.7%, specificity of 77.1% and accuracy of 87.70% for differentiating malignant from benign lesion. The higher Kapp value in the malignant masses supports the theory that malignant masses are more heterogeneous and have more complex microstructure leading to deviation from the gaussian behavior.

These results were similar to a study by Jiang et al[26], in which they proposed Kapp cutoff value of 0.63 and Dapp cutoff value of 1.75 × 10-3 mm2/second to differentiate between benign and malignant sinonasal masses. These results also correlated with the studies done to assess the role of DKI in differentiation of glioma, prostate, liver and breast pathologies[4-7].

None of the DCE-MRI parameters demonstrated a statistically significant difference between benign and malignant sinonasal masses in our study. Although previous studies by Xian et al[32] and Jiang et al[31] reported a significant difference in Ktrans values among these lesions, our findings did not replicate those results. This discrepancy may be attributed to the small and heterogeneous sample size in our cohort, as well as the frequent presence of necrosis, hemorrhage, and an underlying infective or inflammatory background in sinonasal pathologies, which can affect perfusion dynamics and limit the reliability of DCE-MRI parameters. The sinonasal region is particularly prone to motion artifacts due to involuntary movements such as breathing and swallowing. These artifacts can degrade image quality and compromise the accuracy of dynamic contrast measurements, thereby limiting the effectiveness of DCE-MRI in this area.

Among the significant parameters, the Dt and Dapp showed a significant difference between their AUC, rest of the parameters did not show any statistically significant difference among their AUC (Table 4).

According to our study, there is no incremental role of DKI and IVIM over conventional DWI in the differentiation of benign and malignant sinonasal masses. In addition, the total duration of IVIM-DKI sequence was almost double compared to conventional DWI sequence. We could not find any scenario (Indeterminate cases or specific tumor subtypes) where IVIM and DKI parameters showed a diagnostic benefit over conventional DWI. We could not perform a subgroup analysis in our study as sample size was small. Xiao et al[33] assessed the role of IVIM and DKI parameters in differentiating sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma, lymphoma, malignant melanoma and olfactory neuroblastoma from each other. He demonstrated that lymphoma had the highest Kapp and lowest Dapp, Dt, Dx and f compared to other three groups. The malignant melanoma had highest Dx and f.

Our study had some limitations. The sample size was small and a heterogeneous group of pathologies were included in the final analysis, which limited the statistical power, particularly for subgroup analyses. In addition, the b-values were set arbitrarily in the IVIM-DKI sequence, as there are no standardized b-values for the IVIM -DKI sequence in sinonasal masses. Finally, as the ROIs were placed after correlating with the conventional MRI, the analysis of the diffusion parameters was not entirely independent.

In conclusion, the mean ADC from conventional DWI, Dt from IVIM, and Dapp and Kapp from DKI can be used as noninvasive imaging methods for differentiating benign and malignant sinonasal masses. Among these, ADC is the best parameter to differentiate between sinonasal masses. Hence, there is no incremental role of DKI and IVIM as well perfusion parameters over conventional DWI.

| 1. | El-Naggar AK, Chan JK, Rubin Grandis J, Slootweg PJ. WHO classification of head and neck tumours. 4th ed. 2017. |

| 2. | Baliyan V, Das CJ, Sharma R, Gupta AK. Diffusion weighted imaging: Technique and applications. World J Radiol. 2016;8:785-798. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 234] [Article Influence: 23.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 3. | Rosenkrantz AB, Padhani AR, Chenevert TL, Koh DM, De Keyzer F, Taouli B, Le Bihan D. Body diffusion kurtosis imaging: Basic principles, applications, and considerations for clinical practice. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;42:1190-1202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 258] [Cited by in RCA: 301] [Article Influence: 27.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Abdalla G, Dixon L, Sanverdi E, Machado PM, Kwong JSW, Panovska-Griffiths J, Rojas-Garcia A, Yoneoka D, Veraart J, Van Cauter S, Abdel-Khalek AM, Settein M, Yousry T, Bisdas S. The diagnostic role of diffusional kurtosis imaging in glioma grading and differentiation of gliomas from other intra-axial brain tumours: a systematic review with critical appraisal and meta-analysis. Neuroradiology. 2020;62:791-802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wu D, Li G, Zhang J, Chang S, Hu J, Dai Y. Characterization of breast tumors using diffusion kurtosis imaging (DKI). PLoS One. 2014;9:e113240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jia Y, Cai H, Wang M, Luo Y, Xu L, Dong Z, Yan X, Li ZP, Feng ST. Diffusion Kurtosis MR Imaging versus Conventional Diffusion-Weighted Imaging for Distinguishing Hepatocellular Carcinoma from Benign Hepatic Nodules. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2019;2019:2030147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Malagi AV, Netaji A, Kumar V, Baidya Kayal E, Khare K, Das CJ, Calamante F, Mehndiratta A. IVIM-DKI for differentiation between prostate cancer and benign prostatic hyperplasia: comparison of 1.5 T vs. 3 T MRI. MAGMA. 2022;35:609-620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Le Bihan D. What can we see with IVIM MRI? Neuroimage. 2019;187:56-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 354] [Article Influence: 39.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ding Y, Tan Q, Mao W, Dai C, Hu X, Hou J, Zeng M, Zhou J. Differentiating between malignant and benign renal tumors: do IVIM and diffusion kurtosis imaging perform better than DWI? Eur Radiol. 2019;29:6930-6939. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Podgórska J, Pasicz K, Skrzyński W, Gołębiewski B, Kuś P, Jasieniak J, Kiliszczyk A, Rogowska A, Benkert T, Pałucki J, Grabska I, Fabiszewska E, Jagielska B, Kukołowicz P, Cieszanowski A. Perfusion-Diffusion Ratio: A New IVIM Approach in Differentiating Solid Benign and Malignant Primary Lesions of the Liver. Biomed Res Int. 2022;2022:2957759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Mao X, Zou X, Yu N, Jiang X, Du J. Quantitative evaluation of intravoxel incoherent motion diffusion-weighted imaging (IVIM) for differential diagnosis and grading prediction of benign and malignant breast lesions. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e11109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Beyhan M, Sade R, Koc E, Adanur S, Kantarci M. The evaluation of prostate lesions with IVIM DWI and MR perfusion parameters at 3T MRI. Radiol Med. 2019;124:87-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mazaheri Y, Akin O, Hricak H. Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of prostate cancer: A review of current methods and applications. World J Radiol. 2017;9:416-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Malla SR, Bhalla AS, Manchanda S, Kandasamy D, Kumar R, Agarwal S, Shamim SA, Kakkar A. Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging for differentiating head and neck paraganglioma and schwannoma. Head Neck. 2021;43:2611-2622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Alibek S, Zenk J, Bozzato A, Lell M, Grunewald M, Anders K, Rabe C, Iro H, Bautz W, Greess H. The value of dynamic MRI studies in parotid tumors. Acad Radiol. 2007;14:701-710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Srinivasan A, Dvorak R, Perni K, Rohrer S, Mukherji SK. Differentiation of benign and malignant pathology in the head and neck using 3T apparent diffusion coefficient values: early experience. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:40-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wang XY, Yan F, Hao H, Wu JX, Chen QH, Xian JF. Improved performance in differentiating benign from malignant sinonasal tumors using diffusion-weighted combined with dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Chin Med J (Engl). 2015;128:586-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | El-Gerby KM, El-Anwar MW. Differentiating Benign from Malignant Sinonasal Lesions: Feasibility of Diffusion Weighted MRI. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;21:358-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wang F, Sha Y, Zhao M, Wan H, Zhang F, Cheng Y, Tang W. High-Resolution Diffusion-Weighted Imaging Improves the Diagnostic Accuracy of Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced Sinonasal Magnetic Resonance Imaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2017;41:199-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Daga R, Kumar J, Pradhan G, Meher R, Malhotra V, Khurana N. Differentiation of Benign From Malignant Sinonasal Masses Using Diffusion Weighted Imaging and Dynamic Contrast Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2022;36:207-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wang P, Tang Z, Xiao Z, Hong R, Wang R, Wang Y, Zhan Y. Dual-energy CT in differentiating benign sinonasal lesions from malignant ones: comparison with simulated single-energy CT, conventional MRI, and DWI. Eur Radiol. 2022;32:1095-1105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Das A, Bhalla AS, Sharma R, Kumar A, Thakar A, Vishnubhatla SM, Sharma MC, Sharma SC. Can Diffusion Weighted Imaging Aid in Differentiating Benign from Malignant Sinonasal Masses?: A Useful Adjunct. Pol J Radiol. 2017;82:345-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Razek AA, Sieza S, Maha B. Assessment of nasal and paranasal sinus masses by diffusion-weighted MR imaging. J Neuroradiol. 2009;36:206-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | van Rijswijk CS, Kunz P, Hogendoorn PC, Taminiau AH, Doornbos J, Bloem JL. Diffusion-weighted MRI in the characterization of soft-tissue tumors. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2002;15:302-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | White ML, Zhang Y, Robinson RA. Evaluating tumors and tumorlike lesions of the nasal cavity, the paranasal sinuses, and the adjacent skull base with diffusion-weighted MRI. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2006;30:490-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Jiang JX, Tang ZH, Zhong YF, Qiang JW. Diffusion kurtosis imaging for differentiating between the benign and malignant sinonasal lesions. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2017;45:1446-1454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Heffelfinger MJ, Dahlin DC, MacCarty CS, Beabout JW. Chordomas and cartilaginous tumors at the skull base. Cancer. 1973;32:410-420. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 28. | LiVolsi VA. Papillary thyroid carcinoma: an update. Mod Pathol. 2011;24 Suppl 2:S1-S9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 225] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Linh LT, Cuong NN, Hung TV, Hieu NV, Lenh BV, Hue ND, Pham VH, Nga VT, Chu DT. Value of Diffusion Weighted MRI with Quantitative ADC Map in Diagnosis of Malignant Thyroid Disease. Diagnostics (Basel). 2019;9:129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Xiao Z, Tang Z, Qiang J, Wang S, Qian W, Zhong Y, Wang R, Wang J, Wu L, Tang W, Zhang Z. Intravoxel Incoherent Motion MR Imaging in the Differentiation of Benign and Malignant Sinonasal Lesions: Comparison with Conventional Diffusion-Weighted MR Imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2018;39:538-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Jiang J, Xiao Z, Tang Z, Zhong Y, Qiang J. Differentiating between benign and malignant sinonasal lesions using dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI and intravoxel incoherent motion. Eur J Radiol. 2018;98:7-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Xian J, Du H, Wang X, Yan F, Zhang Z, Hao H, Zhao B, Tong Y, Zhang J, Han D. Feasibility and value of quantitative dynamic contrast enhancement MR imaging in the evaluation of sinonasal tumors. Chin Med J (Engl). 2014;127:2259-2264. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Xiao Z, Tang Z, Zheng C, Luo J, Zhao K, Zhang Z. Diffusion Kurtosis Imaging and Intravoxel Incoherent Motion in Differentiating Nasal Malignancies. Laryngoscope. 2020;130:E727-E735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/