Published online Mar 20, 2026. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v16.i1.107307

Revised: April 27, 2025

Accepted: June 30, 2025

Published online: March 20, 2026

Processing time: 326 Days and 17.1 Hours

Adherence to treatment protocol is important prognostic factor for successful result in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis treatment with bracing and/or physiotherapeutic scoliosis specific exercises. However, patients living away from specialized centers, have travelling and financial obstacles to receive proper care. Our clinic developed a specific protocol for online evaluation and treatment sessions.

To evaluate the effectiveness of a hybrid in-person and online treatment protocol for scoliosis treatment.

Retrospective matched case-control study. Our online evaluation required patient digital radiographs and eight standardized clinical photos, in standing and forward bending positions. An intensive in-person program was prescribed, to allow adequate teaching of physiotherapeutic scoliosis specific exercises or brace manufacturing when needed. Then, the patients followed a home-program of exercises, having regular online supervised sessions. They were asked to re-visit our clinic every 3-6 months. Our online intervention group (OIG) (combined in-person and online treatment) was consisted of 118 patients (103 females-15 males, mean Cobb angle 29.4°, Risser 0.8, age 12.6 years). Our inclusion criteria were Cobb angle 10°-40°, Risser 0-2, less 1-year post-menarche for girls, and permanent residence outside of our region. We used a retrospective matched-control group (MCG) with similar characteristics that received only in-person treatment (106 patients, 92 females-14 males, mean Cobb angle 27.1°, Risser 1.1, age 12.9 years). In the last 3 years totally 3092 online sessions were done for the OIG. Compliance was self-reported in both groups. Independent sample t-test were used for sta

Compliance with exercises was significantly better (P = 0.006) in OIG (78.3% > 3 days/week) compared to MCG (52.8% > 3 days/week). In OIG 35% improved, 54% remained stable, and 11% progressed, while in MCG 23.6% improved, 56.6% stable, and 19.8% progressed (P = 0.04). The loss to follow-up was also significantly lower (P = 0.03) in the OIG (6 subjects, 5.1%) compared to MCG (10 subjects, 10.9%).

Our tele-scoliosis-screening and treat protocol significantly improved compliance, monitoring, and final treatment result in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients at high risk of progression. Online supervision can keep patient’s motivation, allowing proper follow-up and can be used for patients with transportation barriers.

Core Tip: This study demonstrates the effectiveness of the tele-scoliosis-screening and treat protocol for patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis facing geographic and financial barriers to in-person care. By integrating online evaluations and supervised exercise sessions with periodic in-person visits, the protocol significantly improved compliance, reduced loss to follow-up, and led to better overall treatment outcomes compared to traditional in-person treatment alone.

- Citation: Karavidas N, Tzatzaliaris D. Tele-scoliosis-screening and treat protocol: A hybrid in-person and online approach for scoliosis treatment in remote patients. World J Methodol 2026; 16(1): 107307

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v16/i1/107307.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v16.i1.107307

Online rehabilitation for spinal deformities became an emerging approach during coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, when many patients could not have in-person access to healthcare providers. Telecommunication technology can provide remote assessment, guidance, and rehabilitation for individuals with conditions like scoliosis, kyphosis, and other spinal conditions, as it allows patients to receive expert care from physical therapists, orthopedic specialists, and rehabilitation professionals without frequent in-person visits[1].

According to Scoliosis Research Society (SRS) and Society on Scoliosis Orthopedic and Rehabilitation Treatment, the treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) can be exclusively by physiotherapeutic scoliosis specific exercises (PSSE) for mild curves below 25° or by a combination of bracing and PSSE for moderate curves between 25° and 40°[2]. Compliance with brace wearing time and PSSE is an important prognostic factor and clinical monitoring of AIS patients during growth is mandatory for a successful outcome[3]. Sometimes a change of curve type can occur, either as positive or negative result, creating the need for modifications in the program of PSSE. The somatometric characteristics change during growth and the brace must be adjusted or substituted. Therefore, a frequent contact of patient and healthcare provider is necessary to ensure the quality of treatment.

Common obstacles for follow-up include travel distance, time to reach the therapeutic team, absence from school for adolescents or absence from work for parents. Lack of motivation or poor performance of exercises can be detected when patient and therapist do not meet each other for prolonged period. Many of our patients permanently live outside of our town or abroad, so we established the tele-scoliosis-screening and treat (TSST) protocol, which was specifically designed for online assessment and treatment of AIS.

Bernhardsson et al[4] in a systematic review of 10 studies, concluded that digital physiotherapy assessment of musculoskeletal disorders may be a viable alternative to face-to-face assessment, showing acceptable to excellent validity and reliability, providing the benefit of convenience for getting remote access to evaluation. Farid et al[5] found high level of agreement between online and in-person measurement of angle trunk rotation (ATR) using a smartphone application. Lau et al[6] in a pilot randomized control trial evaluated the feasibility and effects of a 6-month home-based digitally supported fit program for girls with AIS, showing some benefits on bone health, muscle function, physical activity, and quality of life (QoL) measurements. Mantelatto Andrade et al[7] compared the effects of a traditional rehabilitation program with a telerehabilitation for AIS, showing reduction of Cobb angle for the main curve in both groups, with a greater effect size for the traditional program.

Although the previous authors attempted to use and evaluate remote assessment and treatment for AIS, there is scarce evidence for their use in clinical practice. To date, no study had evaluated the combination of face-to-face and telerehabilitation for AIS treatment. Our aim was to investigate the efficacy of TSST protocol, which was consisted of both online and in-person evaluation and treatment sessions for scoliotic patients during growth.

The study design was retrospective matched case-control, from a prospective database. Inclusion criteria: Idiopathic scoliosis; Cobb angle: 10°-40°; age > 10 years; growth stage Risser 0-2; less 1 year after menstruation for girls; permanent residence outside of our region. Exclusion criteria: Congenital scoliosis; neuromuscular scoliosis; syndromic scoliosis.

Our outcome parameters were Cobb angle (we set a cut-off point of 5° change for progression or improvement), ATR measured by scoliometer, compliance, loss to follow-up, body symmetry measured by Trunk Appearance Clinical Evaluation (TRACE) scale[8] and QoL measured by SRS-22 questionnaire. Patients with initial Cobb angle 10°-24° were prescribed only PSSE-Schroth exercises and those with Cobb angle 25°-40° were prescribed brace and PSSE-Schroth exercises.

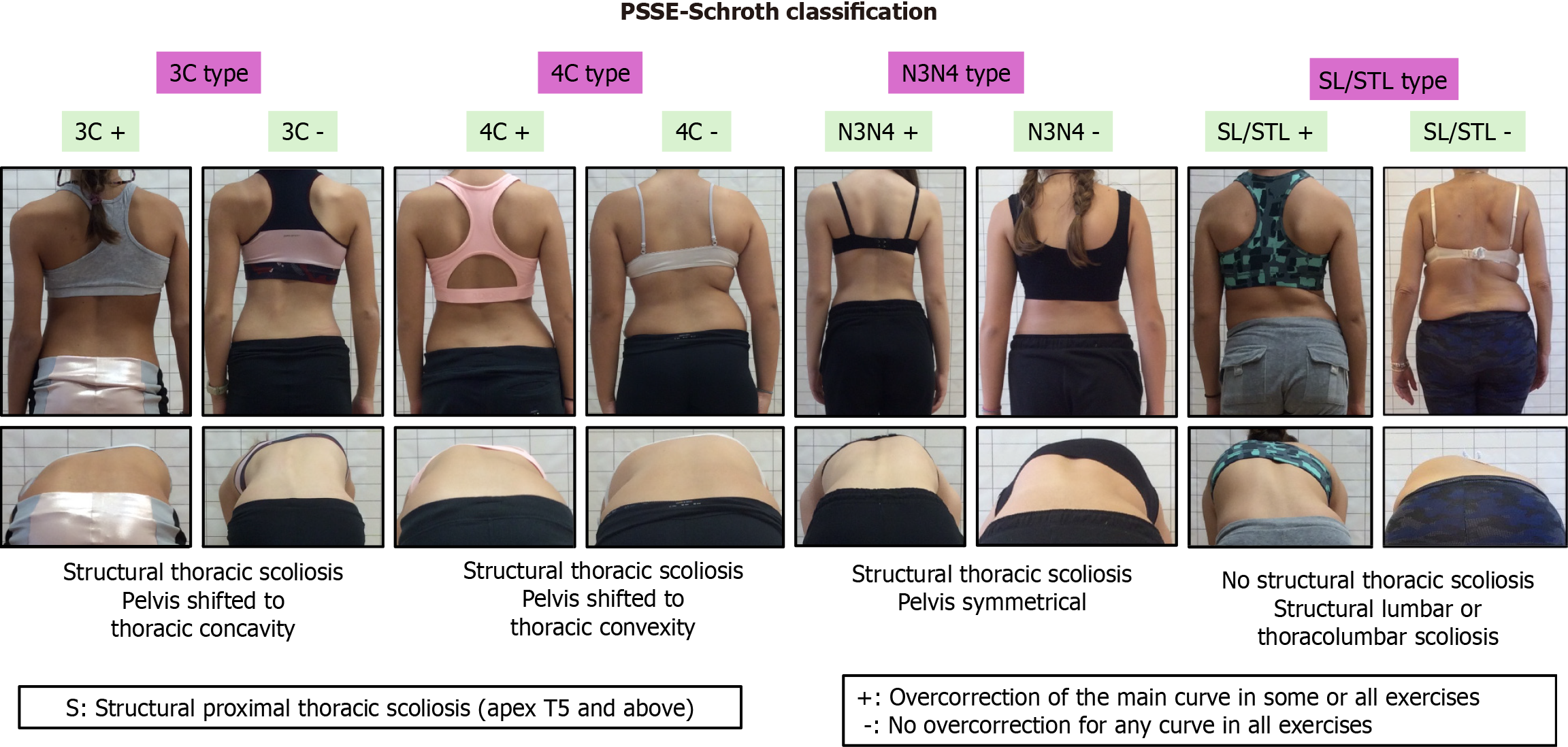

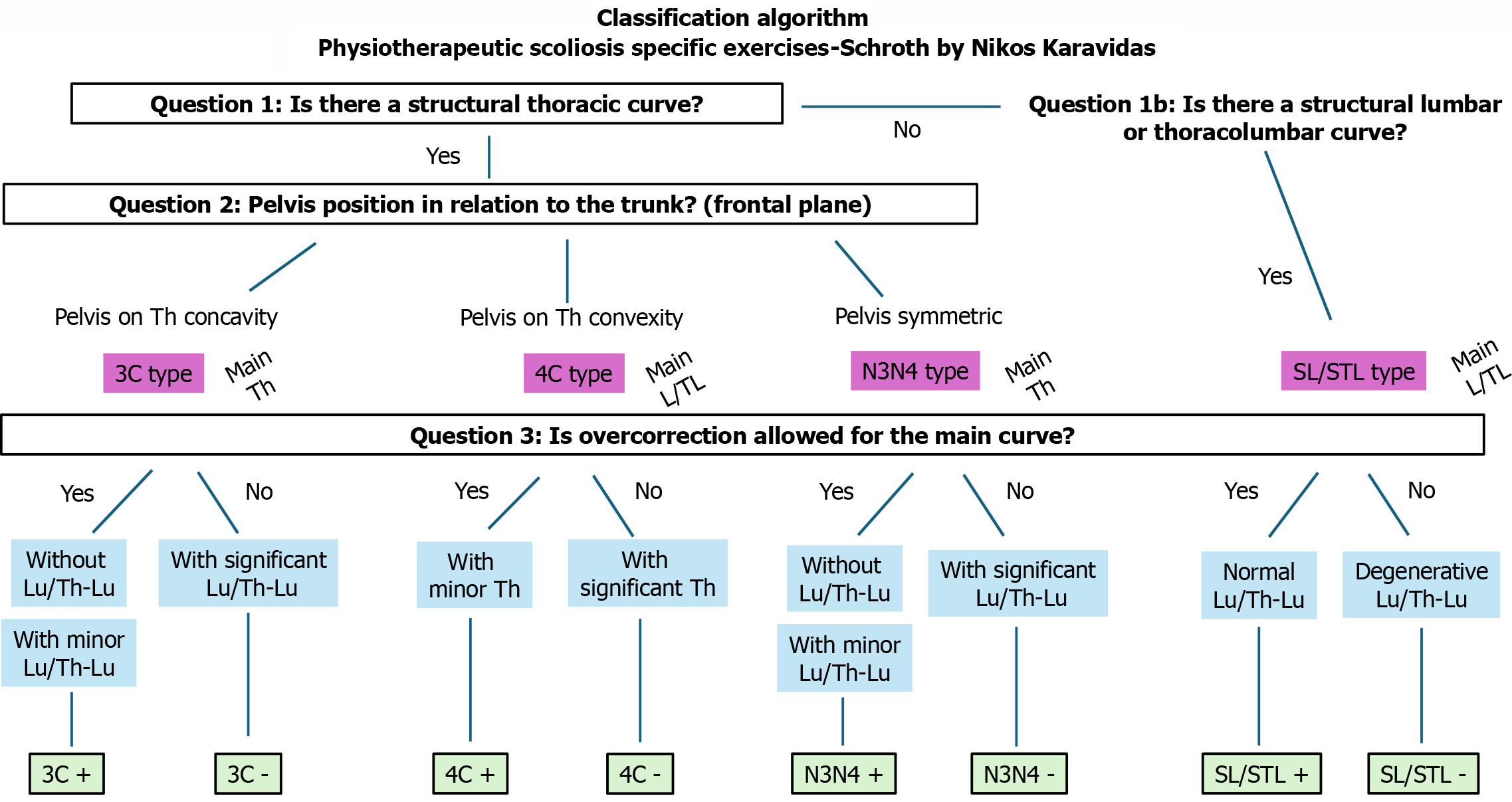

All patients wore asymmetric Cheneau brace type, and the wearing time was individualized according to the risk of progression and ranged from 14 to 22 hours per day. PSSE-Schroth classification was used for brace design and curve type classification for exercises[9]. This classification was firstly described by Karavidas et al[9], including 8 different curve types (Figure 1). The classification is determined by the therapist following a decision tree algorithm, based on three questions, which is presented on Figure 2.

Our TSST protocol consisted of two components: Face-to-face training and telerehabilitation. The online intervention group (OIG), that received combined in-person and online treatment, included 118 patients (103 females, 15 males) with an average major curve Cobb angle of 29.4°, a Risser score of 0.8, and an average age of 12.6 years. Out of 118 subjects, 62 (52.5%) performed only PSSE-Schroth exercises, while 56 (47.5%) combined brace treatment with PSSE-Schroth exercises.

We utilized a retrospective matched-control group (MCG) for comparison, which received exclusively in-person treatment without online sessions between visits to the clinic, having only in-person revisit to us every 3 to 6 months. All MCG subjects were retrospectively extracted from our prospective database to match with the OIG. The MCG had similar baseline characteristics to the OIG, including 106 patients (92 females and 14 males) with an average major curve Cobb angle of 27.1°, a Risser score of 1.1, and an average age of 12.9 years. Among the subjects, 51 (48.1%) performed only PSSE-Schroth exercises, while 55 (51.9%) combined brace treatment with PSSE-Schroth exercises.

The initial consultation for the OIG could be conducted either in person at the beginning of the intensive training in our clinic or via a telehealth appointment. The online consultation allowed patients to understand the treatment plan and decide whether to visit the clinic. Before the online consultation on the Zoom platform, patients were required to send digital X-rays with their dates and eight standardized photos in all directions, both standing and bending, following the sample photo provided for guidance. For patients using braces, additional photos were needed: Four in all directions in a standing position with the brace, and four showing the brace itself (Figure 3). Patients were instructed to stand in a neutral position for the photos and remain without the brace for at least two hours (for braced patients only) to ensure that their posture was not influenced by voluntary or brace correction. The duration of the online consultation was 30-45 minutes, during which detailed medical history was taken, clinical and radiological assessments were analyzed, and patients were advised to participate in an intensive one-week in-person training program at the clinic.

On the first day of the intensive program some additional clinical measurements took place. ATR was measured by Bunnell scoliometer in forward bending test, anthropometric data (standing height, sitting height, body weight) were documented, TRACE scale was used as body symmetry index[8], clinical photos repeated in front of scoliogram and SRS-22 questionnaire for QoL measurement, was filled in by our patients.

PSSE-Schroth method is a program of scoliosis curve-pattern specific exercises with three-dimensional principles of correction based on three-dimensional auto-correction, corrective/rotational breathing, muscle activation and stabilization of corrected posture[9]. The method has proven its effectiveness as exclusive treatment for mild scoliosis and combined with bracing for moderate scoliosis[9]. The exercises were prescribed based on PSSE-Schroth curve type classification and the intensive face-to-face program included 2 hours practical sessions every day. All exercises were video

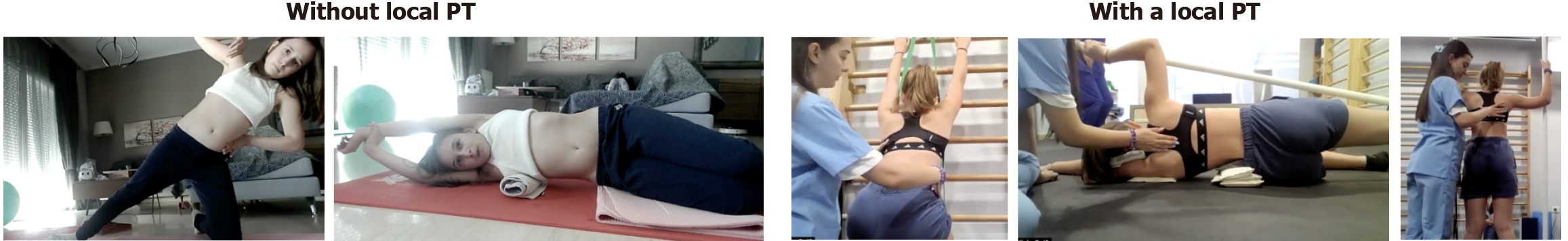

The online component of the TSST protocol consisted of one supervised telerehabilitation session per week conducted via the Zoom platform, each lasting 55 minutes. During these sessions, our therapists instructed patients on performing home-based exercises, making necessary adjustments to positions or equipment as needed. Patients with access to a local physiotherapist had the option to include them in the online sessions (Figure 4). New exercises or modifications to existing exercises were recorded, and video recordings were subsequently sent to the patients. We requested stan

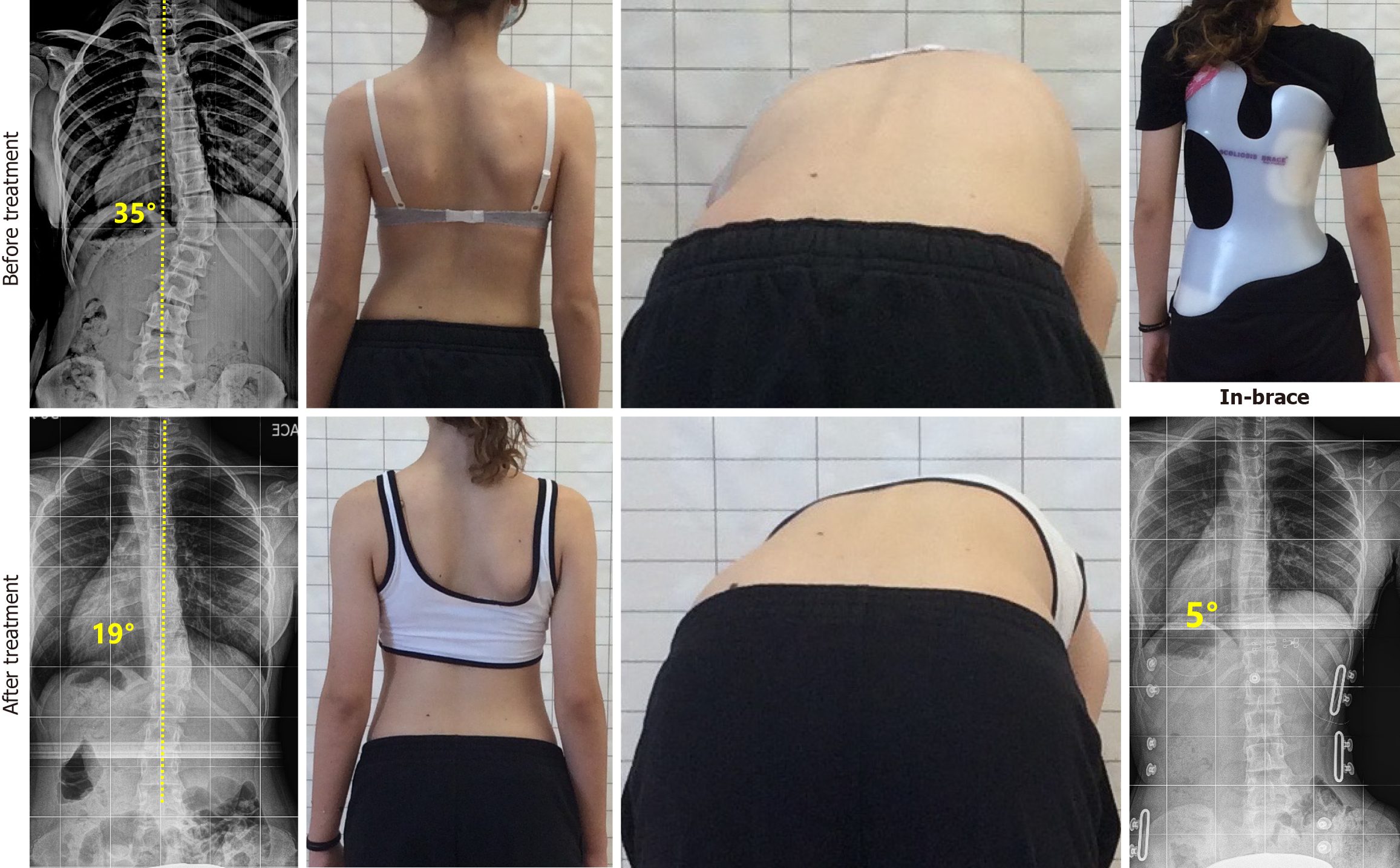

When patients revisited the clinic, every three to six months, clinical measurements were repeated, and they had a supervised face-to-face session for at least two hours. For patients with braces, adjustments to the brace fitting and pressures were made. During the first revisit, which was scheduled after six weeks, an in-brace X-ray was taken to check the correctability of the brace. Compliance was self-reported in both groups monthly both for bracing and exercises. Only 3 patients wore a brace sensor to monitor wearing time, as this technology was not widely available in our country. The mean follow-up time for the OIG was 29.7 months. The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and all participants signed an informed consent paper. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of International Hellenic University, Department of Physiotherapy, Faculty of Health Sciences.

Independent sample t-test was used for statistical analysis, on SPSS software.

In total 3092 online sessions were done for the OIG. 64 (54.2%) remained stable, 41 (34.7%) improved > 5° and 13 (11.1%) progressed > 5°, having a success rate of 88.9% (Figures 5 and 6). On the other hand, for the MCG, the success rate was lower (80.2%, P = 0.04), having 60 (56.6%) stable, 25 (23.6%) improved and 21 (19.8%) progressed (Table 1). Compliance with exercises was significantly better (P = 0.006) in OIG (78.3% > 3 days/week) compared to MCG (52.8% > 3 days/week) (Table 2). The loss to follow-up was also significantly lower (P = 0.03) in the OIG (6 subjects, 5.1%) compared to MCG (10 subjects, 10.9%) (Table 3).

| Stable | Improved | Progressed | Total patients | Success rate, % | P value | |

| Online intervention group | 64 (54.2) | 41 (34.7) | 13 (11.1) | 118 | 88.9 | 0.04 |

| Matched control group | 60 (56.6) | 25 (23.6) | 21 (19.8) | 106 | 80.2 |

| Less than 3 days/week | 3 or more days/week | P value | |

| Online intervention group | 35 (21.7) | 83 (78.3) | 0.006 |

| Matched control group | 50 (47.2) | 56 (52.8) |

| Loss to follow-up | P value | |

| Online intervention group | 6 (5.1) | 0.03 |

| Matched control group | 10 (10.9) |

Mean Cobb angle decreased significantly more in OIG [differences (D) Cobb angle was -4.3°] compared to MCG (D Cobb angle was -1.7°). Both groups improved trunk rotation (D ATR OIG was -2.6°, D ATR MCG was -2.2°, P = 0.06), SRS-22 total score (D SRS-22 OIG was 7.4, D SRS-22 MCG was 5.6, P = 0.07) and TRACE score (D TRACE OIG was 2.2, D TRACE MCG was 1.9, P = 0.17), but no statistical significance was obtained (Table 4). The mean in-brace correction for OIG was 53.6%, while in MCG was 51.4% (P = 0.35).

| Online intervention group | Matched control group | P value | |

| D Cobb angle, major curve | - 4.3° | - 1.7° | 0.03 |

| D ATR, major curve | - 2.6° | - 2.2° | 0.06 |

| D SRS-22 total | 7.4 | 5.6 | 0.07 |

| D TRACE | 2.2 | 1.9 | 0.17 |

The TSST protocol, which integrates both in-person and online treatment sessions, achieved an 88.9% success rate and demonstrated efficacy in managing AIS at the peak of growth with a high risk of progression, particularly for patients with transportation challenges. The treatment outcomes were superior in the OIG compared to the MCG, likely due to higher compliance facilitated by real-time feedback during online sessions which ensures accurate execution of exercises and adherence to therapy.

Our results align with those of Mantelatto Andrade et al[7], who found that telerehabilitation is as effective as face-to-face care. However, their study involved patients aged 10-17 with Cobb angles ranging from 30° to 45° and did not specify the growth stage or report compliance, which could act as confounding factors. This suggests that some patients might have been nearing the end of their growth period with a minimal likelihood of progression. In contrast, our study included only patients around the growth spurt, thereby reinforcing our findings within a population at a clear risk for rapid progression. Furthermore, their follow-up duration was limited to six months, whereas our study had a minimum follow-up period of 29.7 months.

Our findings were similar to Lau et al[6], who reported benefits on bone health, muscle function, physical activity, self-image, and QoL from an online high-intensity interval exercise program for AIS patients. The key difference in our study was the use of supervised scoliosis-specific online sessions and the inclusion of curve progression rate as an outcome. Lau et al[6] had 14 participants in the online group and 16 in the control, with a follow-up of 12 months, while our study had a much larger sample and longer follow-up period.

Bernhardsson et al[4] conducted a systematic review examining various components of digital physiotherapy asse

Mani et al[10] reported high reliability when analyzing sagittal neck posture using a telerehabilitation image-based system for adults with non-specific neck pain, which was compatible with the digital photos used in our study. Similarly, Truter et al[11] found high levels of agreement between face-to-face and telerehabilitation assessments for spinal posture in patients with low back pain. Our study demonstrates that standardized online assessment protocols are effective for conducting reliable postural analyses. Farid et al[5] utilized a smartphone application for remotely measuring trunk rotation. However, this approach was not necessary for our patients, as they had regular in-person visits to our clinic where the ATR was accurately measured and documented by our therapists.

Our study had some limitations. We used a mixed population: Mild curves (< 25°) treated with PSSE-Schroth exercises, and moderate curves (> 25°) treated with braces and PSSE-Schroth exercises. We ensured that the MCG was comparable to the OIG, as the percentages of braced and non-braced patients did not show significant differences. Brace compliance was self-reported since most patients lacked sensors. A key strength was the clear TSST protocol description and our focus on patients with high-risk of progression. Future research should incorporate brace sensors for more accurate measurements. Employing artificial intelligence-based software or smartphone applications, along with selecting a more homogeneous sample, can significantly enhance the validity of the results.

The TSST protocol enhanced adherence to therapy and improved treatment outcomes for AIS patients at high risk of progression. Online supervision supports patient motivation, ensures adequate follow-up, and is particularly beneficial for patients experiencing transportation challenges. Online rehabilitation serves as a cost-effective and time-efficient solution for those located far from the therapeutic team. The primary limitation of online rehabilitation is the absence of hands-on manual techniques; however, its main advantage lies in the effective supervision of home-based exercise programs.

We extend our gratitude to the Department of Physiotherapy, Schroth Scoliosis and Spine Clinic for their assistance in supervising sessions with patients, monitoring compliance, and measuring angle trunk rotation with a scoliometer. We also acknowledge the contributions of brace technicians and orthopedists for their collaboration during this project.

| 1. | Fiani B, Siddiqi I, Lee SC, Dhillon L. Telerehabilitation: Development, Application, and Need for Increased Usage in the COVID-19 Era for Patients with Spinal Pathology. Cureus. 2020;12:e10563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Negrini S, Donzelli S, Aulisa AG, Czaprowski D, Schreiber S, de Mauroy JC, Diers H, Grivas TB, Knott P, Kotwicki T, Lebel A, Marti C, Maruyama T, O'Brien J, Price N, Parent E, Rigo M, Romano M, Stikeleather L, Wynne J, Zaina F. 2016 SOSORT guidelines: orthopaedic and rehabilitation treatment of idiopathic scoliosis during growth. Scoliosis Spinal Disord. 2018;13:3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 407] [Cited by in RCA: 658] [Article Influence: 82.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | van den Bogaart M, van Royen BJ, Haanstra TM, de Kleuver M, Faraj SSA. Predictive factors for brace treatment outcome in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a best-evidence synthesis. Eur Spine J. 2019;28:511-525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bernhardsson S, Larsson A, Bergenheim A, Ho-Henriksson CM, Ekhammar A, Lange E, Larsson MEH, Nordeman L, Samsson KS, Bornhöft L. Digital physiotherapy assessment vs conventional face-to-face physiotherapy assessment of patients with musculoskeletal disorders: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0283013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Farid AR, Hresko MT, Ghessese S, Linden GS, Wong S, Hedequist D, Birch C, Cook D, Flowers KM, Hogue GD. Validation of Examination Maneuvers for Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis in the Telehealth Setting. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2024;106:2249-2255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lau R, Cheuk KY, Tam E, Hui S, Cheng J, Lam TP. Feasibility and effects of 6-month home-based digitally supported E-Fit program utilizing high-intensity interval exercises in girls with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a randomized controlled pilot study. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2021;280:195-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mantelatto Andrade R, Gomes Santana B, Verttú Schmidt A, Eduardo Barsotti C, Pegoraro Baroni M, Tirotti Saragiotto B, Ribeiro AP. Effect of traditional rehabilitation programme versus telerehabilitation in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cohort study. J Rehabil Med. 2024;56:jrm5343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zaina F, Negrini S, Atanasio S. TRACE (Trunk Aesthetic Clinical Evaluation), a routine clinical tool to evaluate aesthetics in scoliosis patients: development from the Aesthetic Index (AI) and repeatability. Scoliosis. 2009;4:3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Karavidas N, Iakovidis P, Chatziprodromidou I, Lytras D, Kasimis K, Kyrkousis A, Apostolou T. Physiotherapeutic Scoliosis-Specific Exercises (PSSE-Schroth) can reduce the risk for progression during early growth in curves below 25°: prospective control study. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2024;60:331-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mani S, Sharma S, Singh DK. Concurrent validity and reliability of telerehabilitation-based physiotherapy assessment of cervical spine in adults with non-specific neck pain. J Telemed Telecare. 2021;27:88-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Truter P, Russell T, Fary R. The validity of physical therapy assessment of low back pain via telerehabilitation in a clinical setting. Telemed J E Health. 2014;20:161-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/