Published online Dec 20, 2025. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v15.i4.105478

Revised: April 17, 2025

Accepted: June 3, 2025

Published online: December 20, 2025

Processing time: 193 Days and 4.6 Hours

Data on the use of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) during Ramadan fasting is limited. No meta-analysis has summarized the safety and effectiveness of GLP-1RAs in these situations.

To evaluate the safety and efficacy of GLP-1RA in patients with T2DM fasting during Ramadan.

Electronic databases were systematically searched for relevant studies that featured GLP-1RA in the intervention arm and other glucose-lowering medications in the control arm. The primary outcome was adverse events (AEs) during Ramadan for both groups; other outcomes included changes in glycemic and anthropometric measures during the peri-Ramadan period.

Four studies [three randomized-controlled trials with low risk of bias (RoB) and one prospective observational study with serious RoB] involving 754 subjects were analyzed. GLP-1RA group achieved greater glycated hemoglobin reduction than the non-GLP-1RA group [mean difference (MD): -0.31%, 95%CI: -0.61 to -0.01, P = 0.04, I2 = 77%] with a lower risk of documented symptomatic hypoglycemia (risk ratio = 0.38, 95%CI: 0.16 to 0.88, P = 0.02). Any AEs, serious AEs, or AEs that led to treatment discontinuation were comparable between the two groups. The GLP-1RA group experienced greater weight loss compared to the non-GLP-1RA group (MD: -2.0 kg, 95%CI: -3.37 to -0.63, P = 0.004, I2 = 95%). There were comparable changes in blood pressure and lipid profile between the two groups. GLP-1RA users experienced higher risks of gastrointestinal AEs, nausea, and vomiting; however, the risks of heartburn, abdominal pain, and diarrhea were similar in both groups.

Limited evidence suggests that GLP-1RAs are safe for T2DM management during Ramadan, offering modest benefits in blood sugar control and weight loss. Large multicenter trials are needed to confirm their safety and efficacy in at-risk populations, improving clinical practice decision-making.

Core Tip: No systematic review and meta-analysis (SR/MA) have previously assessed the safety and efficacy of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus who fast during Ramadan. This SR/MA of 4 studies with 754 participants identified that GLP-1RAs are safe with only exaggerated gastrointestinal side effects, mainly nausea and vomiting. GLP-1RA also appears to be effective in improving glycated hemoglobin and aiding in weight loss, compared to other glucose-lowering medications. However, other cardiometabolic benefits, such as improvements in blood pressure and lipid profile, were not evident. Larger multinational, randomized trials with broader global participation are needed to establish more definitive clinical practice recommendations for using GLP-1RAs during Ramadan fasting.

- Citation: Kamrul-Hasan ABM, Pappachan JM, Ashraf H, Nagendra L, Dutta D, Kuchay MS, Shaikh S. Safety and efficacy of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus fasting during Ramadan: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Methodol 2025; 15(4): 105478

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v15/i4/105478.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v15.i4.105478

Fasting during Ramadan (the ninth month in the Islamic lunar calendar) is one of the five pillars of the Islamic religious faith. During Ramadan, all adult Muslims are required to abstain from consuming food and drink (including medication) from sunrise to sunset[1]. It is estimated that there are approximately 148 million Muslims who live with diabetes worldwide. The fasting duration varies by geographic location and can last up to 19 hours a day in some parts of the world, especially during the summer. The lifestyle changes in Ramadan, especially abstinence from food and drink for long fasting hours and using glucose-lowering drugs (GLDs) for diabetes treatment, may predispose these individuals to develop adverse events (AEs), including dehydration and hypoglycemia[2]. The Diabetes and Ramadan (DaR) 2020 survey, which involved 5865 participants, found that 83.6% of those surveyed fasted during Ramadan, 94.8% fasted for 15 days or more, and 61.9% completed the entire month[3]. Many of these individuals are at risk of developing complications related to fasting and often fast despite medical advice not to do so[4,5]. Consequently, this sizable Muslim population with diabetes that observes fasting during Ramadan needs special attention before and throughout Ramadan.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) are highly recommended for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) by all guidelines, given their glycemic, weight, cardiorenal, hepatic, and metabolic benefits[6]. The use of GLP-1RAs continues to increase[7], and it is presumed that many Muslims with T2DM fasting during Ramadan will utilize these medications. The reduced risk of hypoglycemia and the additional benefit of weight loss or weight main

However, data on GLP-1RA use by patients with T2DM during Ramadan fasting is limited. Due to the limited number of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies with small sample sizes specifically addressing the adverse effects and efficacy of GLP-1RAs in individuals with T2DM who fast during Ramadan, we conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis (SR/MA). Our goal was to investigate whether individuals with T2DM using GLP-1RAs during the fasting month of Ramadan achieve glycemic and other metabolic benefits, with or without an increased risk of adverse effects/events.

This SR/MA was conducted following the procedures described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and is reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist[9,10]. The SR/MA has been registered with PROSPERO (CRD42024637706), and the protocol summary can be accessed online.

No separate ethical approval was needed for this MA, as such approvals already exist for the individual included studies.

A systematic search was conducted across various databases and registers, including MEDLINE (via PubMed), Embase, Web of Science, and ClinicalTrials.gov. This search spanned from the inception of each database to December 25, 2024. Using the Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” the following terms were searched: (1) “Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists”; (2) “GLP-1 receptor agonists”; (3) “GLP-1RA”; (4) “Exenatide”; (5) “Lixisenatide”; (6) “Liraglutide”; (7) “Albiglutide”; (8) “Dulaglutide”; (9) “Semaglutide”; (10) “Tirzepatide”; (11) “Ramadan fasting”; (12) “Religious fasting”; (13) “Type 2 diabetes mellitus”; (14) “Type 2 diabetes”; (15) “Type II diabetes”; (16) “T2DM”; and (17) “T2D”. The search terms were applied to titles and abstracts. The aim was to identify published and unpublished studies in English. Additionally, the search involved reviewing references within the published articles retrieved for this study and relevant journals.

The Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes, and Study design was used as a framework to formulate eligibility criteria for studies in this SR/MA. The patient population (P) consisted of adults of either sex with T2DM fasting during Ramadan; the intervention (I) was any GLP-1RA either as monotherapy or combined with other GLDs for managing T2DM; the comparison or control (C) group comprised individuals receiving GLDs other than a GLP-1RA either as monotherapy or in combination; the outcomes (O) included safety and/or effectiveness of study drugs during the study period; and RCTs or prospective observational/intervention studies were considered as the study type (S) for inclusion. The studies must have at least two arms: (1) One with any GLP-1RA alone or combined with other GLDs (GLP-1RA group); and (2) The other(s) with other GLDs either as monotherapy or combination therapy (non-GLP-1RA group). Exclusion criteria were case reports or case series, retrospective studies, studies conducted in type 1 or other types of diabetes, including patients with both type 1 and type 2 diabetes, studies conducted among pregnant or lactating women, studies without a non-GLP-1RA control arm, and studies not reporting the outcomes of interest. Four review authors independently identified eligible articles according to the above criteria. Discrepancies in opinion on the inclusion of studies were resolved by consensus.

Four review authors conducted data extraction independently by using standardized data extraction forms. The results were consolidated upon identifying multiple publications from a single study group, and relevant data from each article were incorporated into the analyses. The following data were extracted for all the eligible studies and included in the review: (1) First author; (2) Year of publication; (3) The country where the study was conducted; (4) Study design; (5) Major inclusion criteria of the study subjects; (6) GLDs used in the GLP-1RA and non-GLP-1RA groups; (7) sample size; (8) Number of male and female participants; (9) Mean age; (10) Diabetes duration; (11) Body weight; (12) Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c); (13) Systolic and diastolic blood pressure (BP); (14) Lipid profile; and (15) AEs, including hypoglycemia. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus.

The necessary supplementary files of the articles were obtained from the websites of the publishing journals. Further information, if needed, was collected from the corresponding authors of the relevant articles via email. All pertinent information collected in this manner was meticulously incorporated into the MA. Moreover, attrition rates, encompassing dropouts, losses to follow-up, and withdrawals, were meticulously examined.

The primary outcome of interest was the risk of any AEs, including hypoglycemia, in the GLP-1RA group compared to the non-GLP-1RA group. Additional outcomes included the mean difference (MD) of changes in glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), body weight, systolic and diastolic BP, and lipid profile from baseline between the two groups.

The results of the outcomes were reported using risk ratios (RRs) for dichotomous variables and MDs for continuous variables, together with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The Review Manager computer program, version 7.2.0, was used to generate forest plots, which portrayed the RR or MD for the outcomes; the left side of the forest plot favored the GLP-1RA group, and the right side favored the non-GLP-1RA group[11]. Random-effects analysis models were chosen to address the anticipated heterogeneity resulting from variations in population characteristics and study lengths. The inverse variance statistical method was applied for all instances. The SR/MA encompassed forest plots that integrated data from at least two trials. A significance level of P < 0.05 was used.

Three authors independently conducted the risk of bias (RoB) assessment using the Cochrane RoB tool for randomized trials, Version 2 (RoB2), and the RoB in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions, Version 2 (ROBINS-I V2), for the RCTs and non-randomized intervention trials, respectively[12,13]. In discrepancies, the sixth and seventh authors acted as arbitrators to achieve consensus. The RoB VISualization (robvis) web app created RoB plots[14].

The assessment of heterogeneity was initially conducted by studying forest plots. Subsequently, a χ² test was performed using N-1 degrees of freedom and a significance level of 0.05 to determine the statistical significance. The I2 test was also employed in the subsequent analysis[15]. The specifics of understanding I2 values have been explained in depth elsewhere[16].

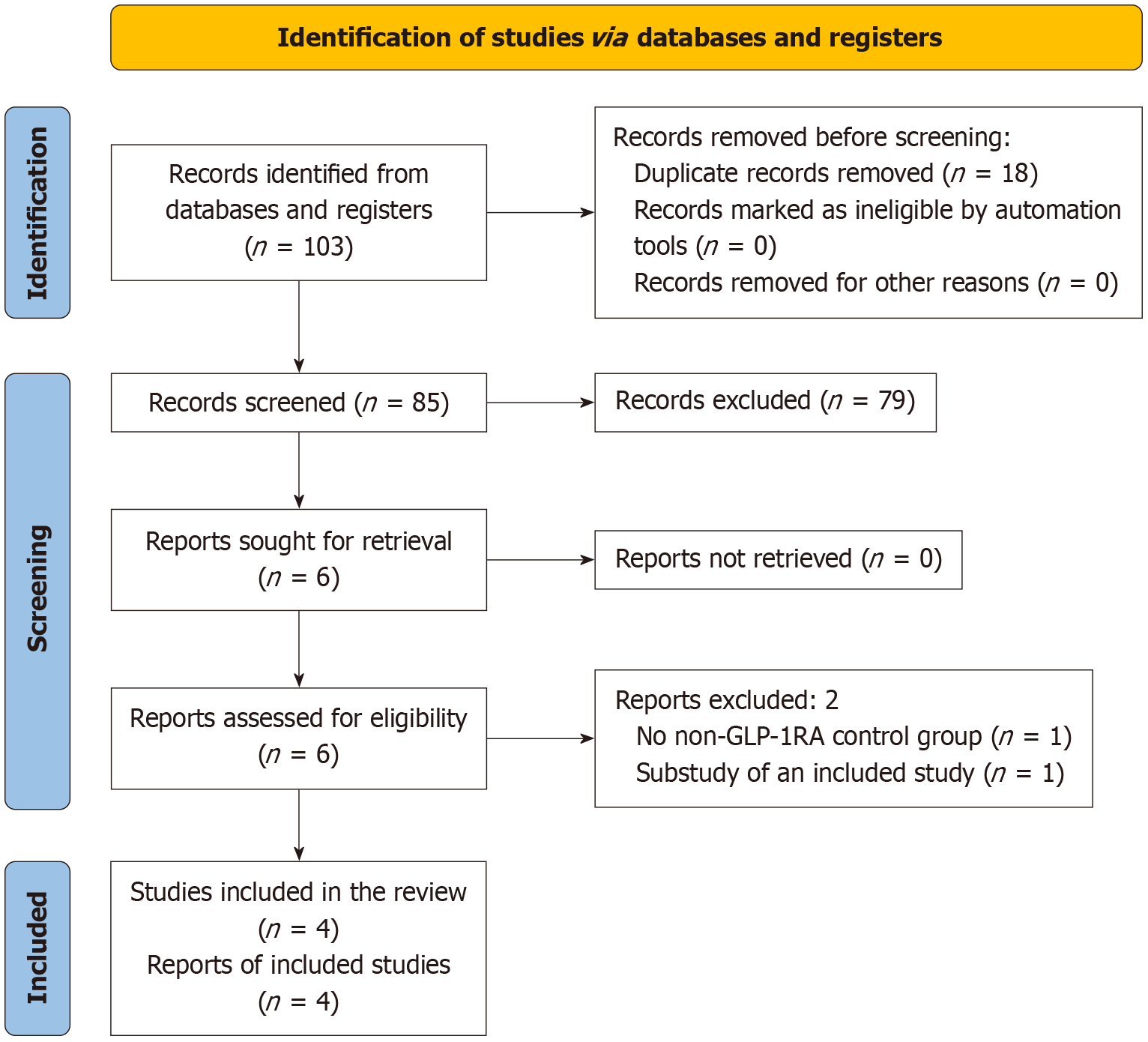

The PRISMA flow diagram of steps in selecting the studies are depicted in Figure 1. The initial search identified 103 articles, narrowed to six after screening titles, abstracts, and subsequent full-text reviews. Finally, four studies involving 754 subjects meeting all the prespecified criteria were included in this SR/MA[17-20]. Two studies were excluded- one did not have a non-GLP-1RA comparator group, and the other was a substudy of an included study[21,22].

The specifics of the included and excluded studies are shown in Table 1[17-20] and Supplementary Table 1[21,22], respectively. Three included studies were randomized, parallel-group, open-label, active-controlled trials[17,18,20]; the other was an open-label, single-center, two-arm parallel-group, prospective observational study[19]. All studies had two arms: (1) One with any GLP-1RA alone or combined with other GLDs (GLP-1RA group); and (2) The other with GLDs other than GLP-1RA either as monotherapy or combination therapy (non-GLP-1RA group). In the GLP-1RA arm, two studies used liraglutide[17,20], one used lixisenatide[18], and the other used semaglutide[19]. The follow-up duration of the studies ranged from 12-33 weeks.

| Ref. | Study design, trial reg. number (if any) | Major inclusion criteria | Groups | GLD used | n | Sex | Age (years), mean (SD) | Duration of diabetes mellitus (years), mean (SD) | Baseline body weight (kg), mean (SD) | Baseline HbA1c (%), mean (SD) | Study duration |

| Azar et al[17], 2016, LIRA-Ramadan, 39 sites in 7 countries | Randomized, parallel-group, open-label, active-controlled trial, NCT01917656 | Age 18-80 years, HbA1c 7%-10%, body mass index ≥ 20 kg/m2, on stable diabetes treatment (MFN ≥ 1 gm + SU MTD) | GLP-1RA | Liraglutide 18 mg + MFN | 171 | M: 85, F: 86 | 54.9 (9.27) | 8.0 (5.26) | 81.0 (17.1) | 8.3 (0.94) | 33 weeks |

| Non- GLP-1RA | SU MTD + MFN | 170 | M: 83, F: 87 | 54.0 (9.33) | 7.2 (4.39) | 83.1 (16.0) | 8.2 (0.91) | ||||

| Hassanein et al[18], 2019, LixiRam, 16 sites in 5 countries | Phase 4, randomized, open-label, parallel-group, clinical trial, NCT02941367 | Uncontrolled diabetes on SU + basal insulin ± one OAD | GLP-1RA | Lixisenatide 20 μgm + basal insulin + MFN | 92 | M: 40, F: 52 | 52.6 (9.5) | 7.1 (4.8) | 76.0 (14.6) | 8.7 (0.7) | 12-20 weeks |

| Non-GLP-1RA | SU + basal insulin + MFN | 92 | M: 43, F: 49 | 54.1 (10.6) | 7.4 (5.4) | 75.0 (11.6) | 8.5 (0.7) | ||||

| Pathan et al[19], 2024, Pathan 2024, Bangladesh Institute of Research and Rehabilitation in Diabetes, Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders, Bangladesh | Open-label, single-center, two-arm parallel-group, prospective observational study | Age > 18 years, on stable GLDs for the last 3 months before enrolment | GLP-1RA | Semaglutide 0.5 mg ± OADs/insulin | 55 | M: 19, F: 36 | 49.05 (9.8) | 7.34 (5.8) | N/A | 7.43 (1.43) | 24 weeks |

| Non-GLP-1RA | OADs ± insulin, no semaglutide | 75 | M: 26, F: 49 | 53.04 (10.9) | 12.37 (6.9) | N/A | 8.10 (1.56) | ||||

| Brady et al[20], 2014, Treat 4 Ramadan, 2 sites in United Kingdom | Randomized, parallel-group, open-label, active-controlled trial | Age ≥ 18 years, on stable dose of MFN or MFN + SU/Pioglitazone, HbA1c 6.5%-12% | GLP-1RA | Liraglutide 12 mg + MFN | 52 | M: 26, F: 26 | 52.2 (10.7) | N/A | 79.0 (11.2) | 7.8 (1.0) | 16 weeks |

| Non-GLP-1RA | MFN + SU | 47 | M: 24, F: 23 | 51.5 (11.1) | N/A | 86.1 (16.9) | 7.6 (1.1) |

Supplementary Figure 1 depicts the RoB across the four studies included in the MA. The overall RoB, assessed by the RoB2 tool, was low in all three RCTs in this SR/MA. The non-randomized prospective trial included in this SR/MA had a serious overall RoB stemming from bias due to confounding, as evaluated by the ROBINS-I assessment tool. Publication bias evaluation was not conducted due to insufficient RCTs (fewer than 10) in the forest plots[23].

The comparison of the proportions of study subjects in the GLP-1RA and non-GLP-1RA groups experiencing AEs during Ramadan fasting is summarized in Table 2. Identical proportions of study subjects in the GLP-1RA and non-GLP-1RA groups had any AEs, serious AEs, or AEs leading to treatment discontinuation. Study subjects in the GLP-1RA group had higher risks of GI AEs [RR = 5.27, 95%CI: 1.40 to 19.89, I2 = 50% (low heterogeneity), P = 0.01], nausea [RR = 14.05, 95%CI: 2.69 to 73.33, I2 = 0% (not important heterogeneity), P = 0.002], and vomiting [RR = 5.96, 95%CI: 1.05 to 33.77, I2 = 0% (not important heterogeneity), P = 0.04] than those in the non-GLP-1RA group. However, the risks of heartburn, abdominal pain, and diarrhea were not statistically increased in the GLP-1RA group compared to the non-GLP-1RA group. Compared to the non-GLP-1RA group, the GLP-1RA group had a lower risk of documented symptomatic hypoglycemia [RR = 0.38, 95%CI: 0.16-0.88, I2 = 45% (low heterogeneity), P = 0.02]; however, the risk of any hypoglycemia was statistically identical in the two groups. None of the participants in either group experienced severe hypoglycemia during Ramadan fasting.

| Outcome variables | Number of included studies | Number of participants with outcome/participants analyzed (%) | Pooled effect size, risk ratio (95%CI) | I2 (%) | P value | |

| GLP-1RA arm | Non- GLP-1RA arm | |||||

| Any AE | 3 | 54/311 | 50/314 | 1.07 (0.76-1.52) | 0 | 0.69 |

| Serious AE | 2 | 2/263 | 0/262 | 4.97 (0.24-102.78) | N/A | 0.30 |

| AE leading to discontinuation of treatment | 2 | 1/263 | 0/262 | 3.00 (0.12-72.70) | N/A | 0.50 |

| Gastrointestinal AEs | 3 | 38/318 | 8/337 | 5.27 (1.40-19.89) | 50 | 0.01 |

| Heartburn | 2 | 7/147 | 1/167 | 4.10 (0.25-68.20) | 50 | 0.33 |

| Nausea | 3 | 17/318 | 1/337 | 14.05 (2.69-73.33) | 0 | 0.002 |

| Vomiting | 2 | 9/263 | 1/262 | 5.96 (1.05-33.77) | 0 | 0.04 |

| Abdominal pain | 2 | 3/147 | 0/167 | 4.61 (0.52-41.28) | 0 | 0.17 |

| Diarrhea | 2 | 5/263 | 3/262 | 1.53 (0.40-5.87) | 0 | 0.53 |

| Any hypoglycemia | 3 | 22/318 | 47/337 | 0.60 (0.19-1.90) | 72 | 0.39 |

| Documented symptomatic hypoglycemia | 3 | 14/310 | 39/312 | 0.38 (0.16-0.88) | 45 | 0.02 |

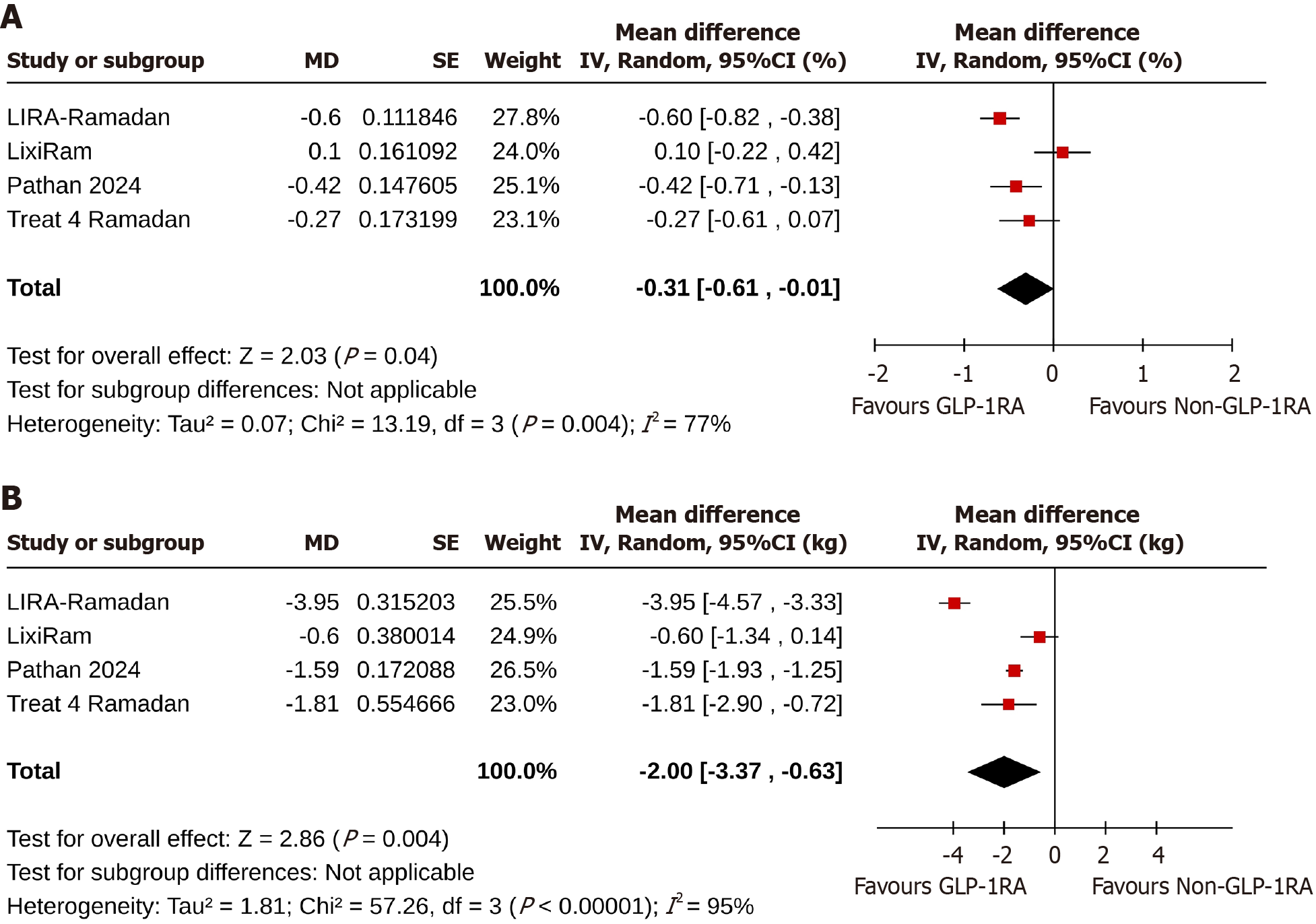

At the end of the studies, change in HbA1c from the baseline was greater in the GLP-1RA than in the non-GLP-1RA group [MD: -0.31%, 95%CI: -0.61 to -0.01, I2 = 77% (high heterogeneity), P = 0.04] (Figure 2A)[17-20].

Study subjects in the GLP-1RA group achieved a greater body weight reduction than the non-GLP-1RA group [MD: -2.0 kg, 95%CI: -3.37 to -0.63, I2 = 95% (high heterogeneity), P = 0.004] (Figure 2B) from baseline to the end of the trials[17-20].

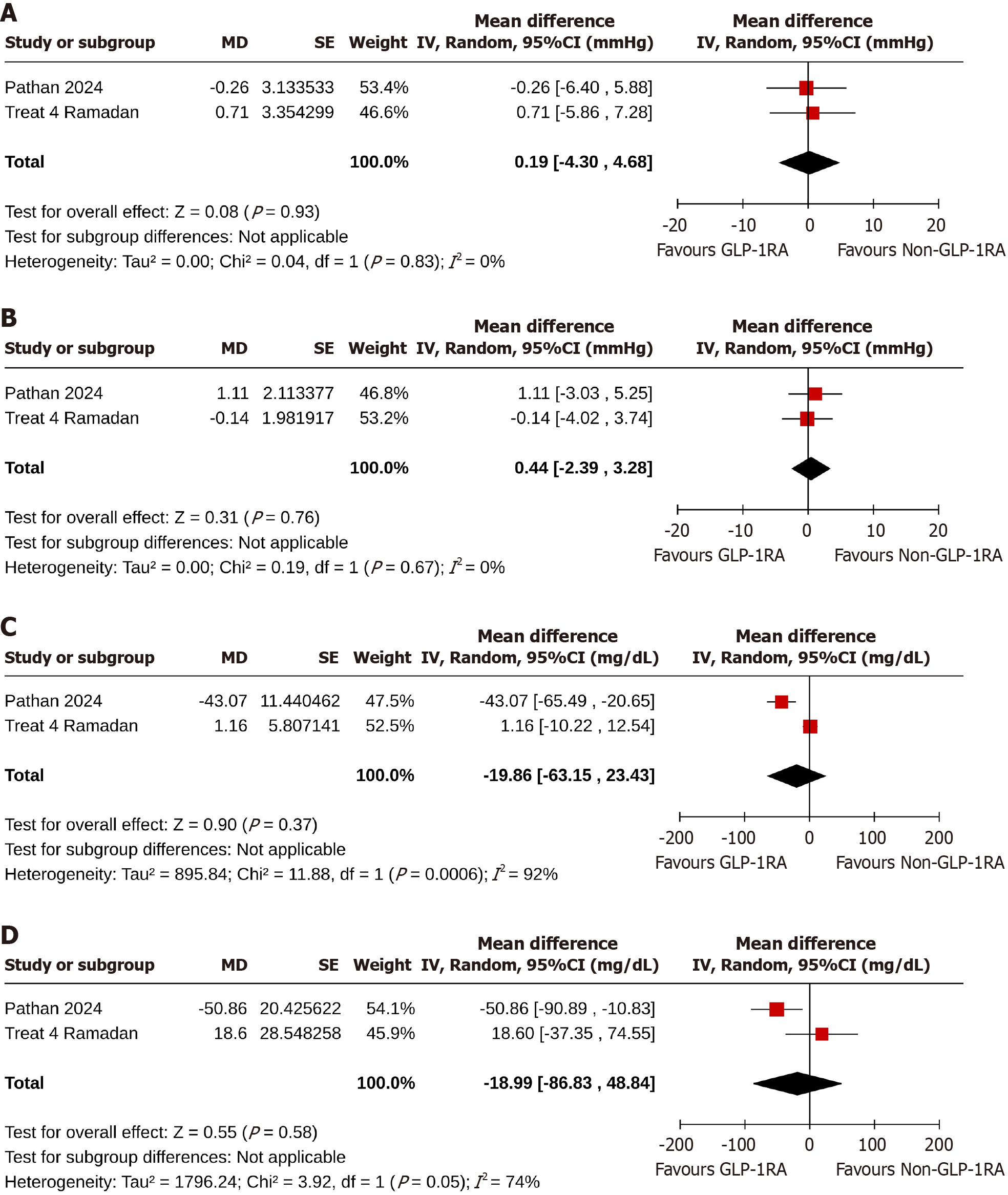

Study subjects in the GLP-1RA group achieved identical changes in systolic BP [MD: 0.19 mmHg, 95%CI: -4.30 to 4.68, I2 = 0% (not important heterogeneity), P = 0.93] (Figure 3A) and diastolic BP [MD: 0.44 mmHg, 95%CI: -2.39 to 3.28, I2 = 0% (not important heterogeneity), P = 0.76] (Figure 3B) than the non-GLP-1RA group[19,20].

At the end of the studies, the two groups achieved comparable changes in total cholesterol [MD: -19.86 mg/dL, 95%CI: -63.15 to 24.43, I2 = 92% (high heterogeneity), P = 0.37] (Figure 3C) and triglyceride [MD: -18.99 mg/dL, 95%CI: -86.83 to 48.84, I2 = 74% (moderate heterogeneity), P = 0.58] (Figure 3D) levels from the baseline values[19,20].

Heterogeneity results: Although the results of some analyses (e.g., effects on glycemic control, body weight, and lipids) presented high heterogeneity, sub-analyses could not be performed due to the limited number of studies included in this research.

This SR/MA analyzed a relatively small dataset from four short-term studies—three RCTs with low RoB and one prospective observational study with serious RoB. The follow-up period ranged from 12 weeks to 33 weeks, involving 754 participants across multiple countries. The SR/MA suggests that compared to other GLDs, the use of drugs in the GLP-1RA class was associated with a statistically significant HbA1c reduction with a significantly lower risk of symptomatic hypoglycemia, without excess risk of serious AEs, and AEs leading to treatment discontinuation. However, as expected, common GI side effects such as nausea and vomiting were observed in the GLP-1RA group without higher risks of heartburn, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. This SR/MA also observed a greater mean body weight reduction from baseline to the end of the trials in participants using GLP-1RA compared to the controls, while there were no significant changes in BP and lipid profiles between the groups.

Medications in the GLP-1RA class are generally safe and lead to substantial weight loss across all ethnic groups, whether or not they have T2DM, as demonstrated by many studies[24-26]. During the prolonged daytime fasting period of Ramadan, the use of GLDs can be risky due to the exaggerated tendency for hypoglycemia and GI side effects. However, our SR/MA suggested that GLP-1RA use was safe and provided additional benefits of significant weight loss and improvement in HbA1c. Interestingly, protection from hypoglycemia was found among participants, making this drug an attractive option for patients during Ramadan compared to other GLDs, especially insulin and insulin secretagogues. Delayed gastric emptying associated with GLP-1RA could slow down the nutrient flow in the GI tract (GIT) and result in a steady glucose supply to the body from the food prior to initiation of fasting, conferring hypoglycemia protection.

Ramadan fasting often resembles time-restricted eating (TRE) behavior, as in many regions worldwide, fasting lasts more than 12 hours, which is linked to weight loss and metabolic health advantages[27,28]. Whether the use of GLP-1RA in such a situation provides additional metabolic and weight reduction benefits during the Ramadan period is an important research question emerging from our observation in this SR/MA, because even for such a short period TRE, the weight loss advantage observed was relatively great. Moreover, the anorexiant properties of these molecules provide an additional benefit in suppressing food cravings during fasting. Food craving can be an important issue during fasting, especially in T2DM with hyperinsulinemia, and the appetite suppression from GLP-1RA use could offer better (fasting) adherence and quality of life (QoL) to individuals with diabetes during Ramadan. Moreover, the slower and steady nutrient supply from delayed upper GIT motility, as mentioned above with hypoglycemia prevention, adds to better adherence and QoL. Therefore, the higher weight loss and metabolic benefits we observed could be from the effects of TRE on body fat mobilization coupled with reduced energy-rich food consumption due to the anorexiant effects of GLP-1RA use.

As expected, GI AEs were significantly higher in the GLP-1RA group. One of the primary therapeutic effects of the GLP-1RA class of drugs is the slowing of food transit, particularly in the upper GIT. This contributes to the anorexiant properties of these compounds, which often result in nausea and vomiting, increasing the risk of drug discontinuation for some individuals[25,29]. However, treatment discontinuation due to GI AEs was not higher. Furthermore, an exaggerated risk of heartburn, abdominal pain, and diarrhea was not observed as in previous studies of GLP-1RAs[30-32], likely due to altered eating behavior during Ramadan. Total food intake can often be lower than usual during Ramadan fasting, and anorexia due to GLP-1RA use can further reduce the food intake, possibly explaining this interesting finding.

No significant changes in systolic or diastolic BP were observed in our study, unlike other studies that reported improvements in BP with GLP-1RAs[33,34]. This SR/MA also did not indicate significant lipid-lowering benefits for those using GLP-1RA drugs during Ramadan, as seen in other studies involving these medications for patients with or without T2DM[25,35,36]. The discrepancies we observed may be attributed to the relatively shorter duration of the studies and the smaller total number of participants in this SR/MA compared to the aforementioned studies. Another possible explanation is the unique eating pattern of Muslims during "Suhur" and "Iftar" meals before and after their daily fast. These meal practices can often cause spikes in glucose and insulin levels in the body, which can alter the effect of medications. Furthermore, while Islam is a global religion with some common religious standards, marked regional differences in food practices exist. For example, in Arab countries, access to dried fruits such as apricots and dates is easier than in countries like those in South America and sub-Saharan Africa, where the consumption of tubers, bread, and other carbohydrates is more common. Thus, identifying the precise reason for the impact on lipid changes would be challenging without a comprehensive investigation into the dietary changes occurring during Ramadan.

Overall, the GLP-1RA group of agents appears to offer good efficacy and safety for T2DM patients who fast during Ramadan. In addition to the usual pharmacological properties of this drug class, beneficial effects may also relate to the psychosocial impact of Ramadan, characterized by moments of prayer, reflection, and forgiveness that are associated with happiness, reduced stress levels, and lower stress hormones (e.g., cortisol and adrenaline), which can improve insulin resistance and the drug's effect.

We also acknowledge a few limitations. In this SR/MA, the analyzed data is limited to a widely common chronic illness such as T2DM. The follow-up period was relatively short, lasting only 12 weeks to 33 weeks for a lifelong disease, and we do not have the differential effects of the intervention specific to the fasting period and the remaining observation period. Moreover, the study data were collected from a limited number of countries, while Ramadan is a significant religious observance for Muslims worldwide, who have varied cultural, nutritional, and physical practices. Consequently, the wide applicability of our study results may be limited. Moreover, the RoB was low in the three included RCTs, though serious RoB was present in the prospective observational study.

We were unable to assess the socio-economic impact of the efficacy and safety of GLP-RA in this study. Although they are expensive, these drugs may be cost-effective due to their remarkable effectiveness and safety, especially considering the high risk of healthcare costs related to AEs during fasting. Therefore, public health authorities and policymakers should give serious consideration to this option for patients. Despite these limitations, this is the first comprehensive SR/MA to evaluate the effects of GLP-1RAs in patients with T2DM who fast during Ramadan.

This SR/MA, based on limited data from a few small-scale studies across various countries, suggests that GLP-1RA may be safe and modestly effective in maintaining glycemic control compared to other GLDs in patients with T2DM during Ramadan fasting. Though the GI AEs appear higher, that did not result in treatment discontinuation. Even if weight loss might be an advantage, other positive cardiometabolic outcomes, such as improvements in lipid profiles and reductions in BP associated with GLP-1RA drugs, were not evident in this SR/MA. Comprehensive multinational RCTs with broader global representation are necessary to strengthen the evidence base for making more robust clinical practice recommendations about the appropriate use of GLP-1RAs during Ramadan.

We are thankful to Dr. Marina George Kudiyirickal MSc, MJDF-RCS, PhD for providing us the audio core tip of this article

| 1. | Ochani RK, Shaikh A, Batra S, Pikale G, Surani S. Diabetes among Muslims during Ramadan: A narrative review. World J Clin Cases. 2023;11:6031-6039. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 2. | Hassanein MM, Hanif W, Malek R, Jabbar A. Changes in fasting patterns during Ramadan, and associated clinical outcomes in adults with type 2 diabetes: A narrative review of epidemiological studies over the last 20 years. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2021;172:108584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hassanein M, Hussein Z, Shaltout I, Wan Seman WJ, Tong CV, Mohd Noor N, Buyukbese MA, El Tony L, Shaker GM, Alamoudi RM, Hafidh K, Fariduddin M, Batais MA, Shaikh S, Malek PR, Alabbood M, Sahay R, Alshenqete AM, Yakoob Ahmedani M. The DAR 2020 Global survey: Ramadan fasting during COVID 19 pandemic and the impact of older age on fasting among adults with Type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2021;173:108674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Pratama SA, Kurniawan R, Chiu HY, Kuo HJ, Ekpor E, Kung PJ, Al Baqi S, Hasan F, Romadlon DS. Glycemic fluctuations, fatigue, and sleep disturbances in type 2 diabetes during ramadan fasting: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2025;20:e0312356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Baynouna Alketbi L, Afandi B, Nagelkerke N, Abdubaqi H, Al Nuaimi RA, Al Saedi MR, Al Blooshi FI, Al Blooshi NS, AlAryani AM, Al Marzooqi NM, Al Khouri AA, Al Mansoori SA, Hassanein M. Validation of the IDF-DAR risk assessment tool for Ramadan fasting in patients with diabetes in primary care. Front Clin Diabetes Healthc. 2025;6:1426120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. Summary of Revisions: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2025. Diabetes Care. 2025;48:S6-S13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 34.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Arnold SV, Tang F, Cooper A, Chen H, Gomes MB, Rathmann W, Shimomura I, Vora J, Watada H, Khunti K, Kosiborod M. Global use of SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists in type 2 diabetes. Results from DISCOVER. BMC Endocr Disord. 2022;22:111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hassanein M, Afandi B, Yakoob Ahmedani M, Mohammad Alamoudi R, Alawadi F, Bajaj HS, Basit A, Bennakhi A, El Sayed AA, Hamdy O, Hanif W, Jabbar A, Kleinebreil L, Lessan N, Shaltout I, Mohamad Wan Bebakar W, Abdelgadir E, Abdo S, Al Ozairi E, Al Saleh Y, Alarouj M, Ali T, Ali Almadani A, Helmy Assaad-Khalil S, Bashier AMK, Arifi Beshyah S, Buyukbese MA, Ahmad Chowdhury T, Norou Diop S, Samir Elbarbary N, Elhadd TA, Eliana F, Ezzat Faris M, Hafidh K, Hussein Z, Iraqi H, Kaplan W, Khan TS, Khunti K, Maher S, Malek R, Malik RA, Mohamed M, Sayed Kamel Mohamed M, Ahmed Mohamed N, Pathan S, Rashid F, Sahay RK, Taha Salih B, Sandid MA, Shaikh S, Slim I, Tayeb K, Mohd Yusof BN, Binte Zainudin S. Diabetes and Ramadan: Practical guidelines 2021. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;185:109185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.5. United Kingdom: Cochrane, 2024. |

| 10. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44932] [Cited by in RCA: 51923] [Article Influence: 10384.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 11. | Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 7.2.0. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2024. Available from: https://revman.cochrane.org. |

| 12. | Higgins JPT, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Sterne JAC. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.4. United Kingdom: Cochrane, 2023. |

| 13. | Sterne JAC, Hernán MA, McAleenan A, Reeves BC, Higgins JPT. Chapter 25: Assessing risk of bias in a non-randomized study. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.5. United Kingdom: Cochrane, 2024. |

| 14. | McGuinness LA, Higgins JPT. Risk-of-bias VISualization (robvis): An R package and Shiny web app for visualizing risk-of-bias assessments. Res Synth Methods. 2021;12:55-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 613] [Cited by in RCA: 3311] [Article Influence: 551.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39087] [Cited by in RCA: 48642] [Article Influence: 2114.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 16. | von Hippel PT. The heterogeneity statistic I(2) can be biased in small meta-analyses. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15:35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 384] [Cited by in RCA: 871] [Article Influence: 79.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Azar ST, Echtay A, Wan Bebakar WM, Al Araj S, Berrah A, Omar M, Mutha A, Tornøe K, Kaltoft MS, Shehadeh N. Efficacy and safety of liraglutide compared to sulphonylurea during Ramadan in patients with type 2 diabetes (LIRA-Ramadan): a randomized trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18:1025-1033. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hassanein MM, Sahay R, Hafidh K, Djaballah K, Li H, Azar S, Shehadeh N, Hanif W. Safety of lixisenatide versus sulfonylurea added to basal insulin treatment in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus who elect to fast during Ramadan (LixiRam): An international, randomized, open-label trial. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;150:331-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Pathan MF, Akter N, Selim S, Amin MF, Afsana F, Saifuddin M, Kamrul-hasan ABM, Mustari M, Chakraborty AK, Hossain RMM. Safety and Efficacy of Semaglutide Use in Diabetes during Ramadan Fasting: A Real-world Experience from Bangladesh. Bangladesh J Endocr Metab. 2024;3:26-35. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Brady EM, Davies MJ, Gray LJ, Saeed MA, Smith D, Hanif W, Khunti K. A randomized controlled trial comparing the GLP-1 receptor agonist liraglutide to a sulphonylurea as add on to metformin in patients with established type 2 diabetes during Ramadan: the Treat 4 Ramadan Trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014;16:527-536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hassanein M, Malek R, Al Sifri S, Sahay RK, Buyukbese MA, Djaballah K, Melas-Melt L, Shaltout I. Safety and Effectiveness of Concomitant iGlarLixi and SGLT-2i Use in People with T2D During Ramadan Fasting: A SoliRam Study Sub-analysis. Diabetes Ther. 2024;15:2309-2322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sahay R, Hafidh K, Djaballah K, Coudert M, Azar S, Shehadeh N, Hanif W, Hassanein M. Safety of lixisenatide plus basal insulin treatment regimen in Indian people with type 2 diabetes mellitus during Ramadan fast: A post hoc analysis of the LixiRam randomized trial. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;163:108148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Debray TPA, Moons KGM, Riley RD. Detecting small-study effects and funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analysis of survival data: A comparison of new and existing tests. Res Synth Methods. 2018;9:41-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wen Z, Sun W, Wang H, Chang R, Wang J, Song C, Zhang S, Ni Q, An X. Comparison of the effectiveness and safety of GLP-1 receptor agonists for type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with overweight/obesity: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2025;222:111999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Yao H, Zhang A, Li D, Wu Y, Wang CZ, Wan JY, Yuan CS. Comparative effectiveness of GLP-1 receptor agonists on glycaemic control, body weight, and lipid profile for type 2 diabetes: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2024;384:e076410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Reference Citation Analysis (13)] |

| 26. | Alkhezi OS, Alahmed AA, Alfayez OM, Alzuman OA, Almutairi AR, Almohammed OA. Comparative effectiveness of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists for the management of obesity in adults without diabetes: A network meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Obes Rev. 2023;24:e13543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 28.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Pavlou V, Cienfuegos S, Lin S, Ezpeleta M, Ready K, Corapi S, Wu J, Lopez J, Gabel K, Tussing-Humphreys L, Oddo VM, Alexandria SJ, Sanchez J, Unterman T, Chow LS, Vidmar AP, Varady KA. Effect of Time-Restricted Eating on Weight Loss in Adults With Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2339337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 26.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Liu HY, Eso AA, Cook N, O'Neill HM, Albarqouni L. Meal Timing and Anthropometric and Metabolic Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7:e2442163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Moiz A, Filion KB, Toutounchi H, Tsoukas MA, Yu OHY, Peters TM, Eisenberg MJ. Efficacy and Safety of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists for Weight Loss Among Adults Without Diabetes : A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Ann Intern Med. 2025;178:199-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 52.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Liu BD, Udemba SC, Liang K, Tarabichi Y, Hill H, Fass R, Song G. Shorter-acting glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists are associated with increased development of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and its complications in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a population-level retrospective matched cohort study. Gut. 2024;73:246-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Austregésilo de Athayde De Hollanda Morais B, Martins Prizão V, de Moura de Souza M, Ximenes Mendes B, Rodrigues Defante ML, Cosendey Martins O, Rodrigues AM. The efficacy and safety of GLP-1 agonists in PCOS women living with obesity in promoting weight loss and hormonal regulation: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Diabetes Complications. 2024;38:108834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Iqbal J, Wu HX, Hu N, Zhou YH, Li L, Xiao F, Wang T, Jiang HL, Xu SN, Huang BL, Zhou HD. Effect of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists on body weight in adults with obesity without diabetes mellitus-a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Obes Rev. 2022;23:e13435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 30.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kamarullah W, Pranata R, Wiramihardja S, Tiksnadi BB. Role of Incretin Mimetics in Cardiovascular Outcomes and Other Classical Cardiovascular Risk Factors beyond Obesity and Diabetes Mellitus in Nondiabetic Adults with Obesity: a Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2025;25:203-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 34. | Wong HJ, Toh KZX, Teo YH, Teo YN, Chan MY, Yeo LLL, Eng PC, Tan BYQ, Zhou X, Yang Q, Dalakoti M, Sia CH. Effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists on blood pressure in overweight or obese patients: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Hypertens. 2025;43:290-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Chae Y, Kwon SH, Nam JH, Kang E, Im J, Kim HJ, Lee EK. Lipid profile changes induced by glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2024;17:721-729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Ansari HUH, Qazi SU, Sajid F, Altaf Z, Ghazanfar S, Naveed N, Ashfaq AS, Siddiqui AH, Iqbal H, Qazi S. Efficacy and Safety of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists on Body Weight and Cardiometabolic Parameters in Individuals With Obesity and Without Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Endocr Pract. 2024;30:160-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 31.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/