Published online Dec 20, 2025. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v15.i4.105287

Revised: April 2, 2025

Accepted: April 15, 2025

Published online: December 20, 2025

Processing time: 199 Days and 19.2 Hours

Glaucoma is the leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide, with 60.5 million affected individuals, of whom 11 million are from India. Due to its asym

To identify awareness, knowledge, and attitudes about glaucoma among heal

This cross-sectional study was conducted at a tertiary care institute in Eastern India. Data were collected from 423 participants by systematic stratified sampling after Institutional Ethics Committee approval via a pretested, self-designed, semistructured, validated questionnaire. Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences Software v22.0. Continuous variables are expressed as the means ± SD for parametric values and medians with interquartile ranges for nonparametric values. The associations between the variables were studied via multivariate linear and logistic regression. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Most respondents were 20–30 years old (n = 345, 81.6%). The knowledge regarding glaucoma was good, and almost 56.3% of the participants gained knowledge from their medical training. The majority were aware that it has a familial predisposition and is secondary to high intraocular pressure, leading to irreversible peripheral vision loss. Only 42% knew about the life-long requirements of treatment. The resident group scored highest on knowledge- and attitude-based questions, whereas the faculty group scored highest on practice-based questions. Although 62% of the nursing staff had good attitude scores, their knowledge and practice scores were lower. The occupation group response difference was statistically significant (P < 0.05) for all the knowledge-based questions.

Although the majority of healthcare providers are aware of glaucoma, there is a dearth of knowledge about treatment modalities. Education via seminars and media can improve their knowledge, attitudes, and practices.

Core Tip: Our study aims to understand the current knowledge, attitude, practice, and awareness level among healthcare professionals decades after the worldwide awareness program on glaucoma, such as the World Glaucoma Week celebration. We are surprised that healthcare workers still lack awareness of glaucoma. Although the attitude shown was enthusiastic, many professionals require repeated seminars and awareness programs to enhance healthcare professionals' knowledge and practice patterns to increase their awareness in the community.

- Citation: Nayak B, Chakraborty K, Palanisamy S, Rathod RS, Parija S, Panda BB. Knowledge, attitudes, and practice patterns regarding glaucoma among medical students and healthcare professionals in Eastern India. World J Methodol 2025; 15(4): 105287

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v15/i4/105287.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v15.i4.105287

Glaucoma is characterized by a group of ocular conditions with progressive, irreversible optic nerve damage presenting specific optic disc features and visual field defect patterns[1-3]. The disease remains underdiagnosed among the public (nearly 75%), especially in developing countries, due to a lack of awareness[1,2] and the asymptomatic nature of the disease, especially with fewer follow-up visits[3,4]. Among all causes of blindness, glaucoma is the second most preventable cause, and intraocular pressure (IOP) is a modifiable risk factor[1,2,4,5]. In 2010, nearly 60.5 million people worldwide had glaucoma, which is expected to increase to 111.8 million by 2040[6,7]. Glaucoma not only causes blindness but also interferes with day-to-day activities, affecting the economy and quality of life[1].

Previous studies regarding the awareness of glaucoma among patients have shown that half of them were unaware of their condition at the time of diagnosis and hence presented with an advanced stage of the disease[8]. A community-based study in Nigeria highlighted the importance of community outreach programs with regular screening and patient education in primary health care[9]. A cross-sectional study conducted at Lome reported that 92.3% of healthcare professionals were aware of the grave consequences of glaucoma[3]. Another similar study in northern India reported that most (80.7%) physicians knew about the disease, and 24% were unaware of its familial predisposition[2]. A significant lacuna in the knowledge and awareness of glaucoma among healthcare professionals in Eastern India justifies the study.

To assess glaucoma awareness among healthcare workers in a tertiary care hospital.

Comparative analysis of knowledge, attitudes, and practice patterns among health care workers in a tertiary hospital regarding glaucoma. The Department of Ophthalmology conducted this hospital-based cross-sectional study at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS, Bhubaneswar; Odisha, India). All health care workers and staff working at AIIMS, Bhubaneswar, except health care workers in ophthalmology, were included in this study.

Study design: Hospital-based cross-sectional study.

Study setting: Department of Ophthalmology, AIIMS, Bhubaneswar.

Study participants: All health care workers and staff working at AIIMS, Bhubaneswar.

Study participant criteria: Inclusion criterion was participants working at this institution. Exclusion criteria were participants who were not willing to participate in the study and healthcare workers in the Department of Ophthalmology.

In a previous study performed at a tertiary care institute in northern India, 47.1% of the participants reported that high IOP causes optic nerve damage, leading to glaucoma[2]. An absolute error of 5%, with 95% confidence and a nonresponse rate of 10%, was considered. The minimum sample size required was 422 participants. As mentioned in the study instrument, systematic stratified sampling of equal samples from each stratum (job profile) was considered.

The sample size was calculated with the formula (N = [Z_((1-α) × (PQ⁄d)])2, where N = minimum sample size needed, Z_((1-α)) = 1.96 considering an α error of 0.05 (95% confidence), P = knowledge related to glaucoma was assumed to be 47.1% (7), and Q = (1-P), d = error of 2.5 points, was considered acceptable.

After written informed consent was obtained from the study participants, a pretested, self-designed semistructured questionnaire was used for data collection. The questionnaire was translated into the local vernacular language (Odia) and back-translated to retain the original intended meaning. The questionnaire had two parts. Part A included all of the demographic information such as age, sex, education status, and type of job. Part B included questions on awareness, knowledge, and attitudes, which were asked of all health professionals. For awareness about glaucoma, the first question was "Have you ever heard of glaucoma?". If the answer was "No", the participant was considered unaware of glaucoma, and further questions about knowledge and attitudes were not asked. However, if the answer was "Yes", another question was asked about the participant’s awareness of glaucoma and his/her ideas. Hearing the term "glaucoma" was not considered, as the participant was aware of glaucoma if he/she could not answer the second question on awareness. Then questions concerning knowledge and attitudes were further asked.

Data were collected using a pretested, self-designed semistructured questionnaire. Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences Software (SPSS) version 22.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk, NY, United States). Continuous variables are expressed as the means ± SD for parametric values and medians with interquartile ranges for nonparametric values. The categorical variables are expressed as percentages or proportions. Associations between the variables were determined with appropriate statistical tests of significance. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

There were 423 participants in this study, namely, 183 (43.3%) males and 240 (56.7%) females at a proportion of 1:1.3. Only 50 nursing students, 100% of whom were females, participated. The majority (81.6%) of respondents were young (20-30 years; n = 345, 81.6%) and were mostly students and nursing officers, as described in Table 1.

| Nursing students (n = 50) | MBBS students | Resident doctors (n = 40) | Consultant (n = 40) | Nursing officer | Paramedical staff | Total (n = 423) | |

| Age group | |||||||

| 20-30 years | 50 (100) | 122 (100) | 35(87.5) | 0 (0) | 137 (85.0) | 1 (10) | 345 (81.6) |

| 31-40 years | 0 (0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (12.5) | 14 (35.0) | 24 (15.0) | 9 (90) | 52 (12.3) |

| 41-50 years | 0 (0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.00) | 26 (65.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 26 (6.1) |

| 51-60 years | 0 (0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 0 (0) |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 0 (0) | 85(69.7) | 21 (52.5) | 34 (85.0) | 42 (26.1) | 1 (10.0) | 183 (43.3) |

| Female | 50 (100) | 37 (30.3) | 19 (47.5) | 6 (15.0) | 119 (74.9) | 9 (90.0) | 240 (56.7) |

Knowledge regarding glaucoma was good among all groups. Most of the participants (95.2%) were aware of glaucoma. Almost 56.3% of the participants gained knowledge about glaucoma via medical training. Among the participants, 210 (49.6%) were aware of World Glaucoma Week celebration. Most of the participants were aware that high IOP causes blindness. Among all of the participants, resident doctors had more knowledge about glaucoma. The responses to knowledge-based questions were compiled, and the difference between the occupation groups was statistically significant (P < 0.05) for all five questions (Table 2).

| Nursing students (n = 50) | MBBS students | Resident doctors (n = 40) | Consultants (n = 40) | Nursing staff | Paramedical staff | P value | |

| Q1. Have you heard about glaucoma? | |||||||

| Yes | 50 (100) | 106 (86.9) | 38 (95.0) | 40(100) | 160 (99.4) | 9 (90.0) | < 0.0011 |

| No | 0 (0) | 16 (13.1) | 2 (5.0) | 0 (0) | 1(0.6) | 1 (10.0) | |

| Q2. How do you explain glaucoma? | |||||||

| High eye pressure | 13 (26) | 25 (20.4) | 21 (52.5) | 25 (62.5) | 68 (42.2) | 2 (20) | < 0.0011 |

| High pressure causing blindness | 26 (52) | 54 (44.2) | 17 (42.5) | 27 (67.5) | 85 (52.8) | 6 (60) | |

| Damage to the eye nerve | 9 (18) | 30 (24.5) | 27 (67.5) | 10 (25) | 37 (22.9) | 1 (10) | |

| Causes visual field loss | 1 (2) | 11 (9) | 22 (55) | 10 (25) | 34 (21.1) | 0 | |

| Others | 0 | 0 | 3 (1) | 1 (10) | |||

| Q3. How did you learn about glaucoma? | |||||||

| Mass media | 2 (4) | 12 (9.8) | 1 (2.5) | 0 | 4 (2) | 0 | < 0.0011 |

| Friend | 3 (6) | 33 (27) | 1 (2.5) | 2 (5) | 10 (6.2) | 0 | |

| Doctor | 12 (24) | 36 (29.5) | 10 (25) | 14 (35) | 29 (18) | 2 (20) | |

| Medical training | 32 (64) | 17 (13.9) | 28 (70) | 26 (65) | 128 (79.5) | 7 (70) | |

| Brochure | 0 (0) | 3 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Others | 1 (2) | 4 (2.2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (10) | |

| Q4. Does anyone in your family have glaucoma? | |||||||

| Yes | 5 (10) | 7 (5) | 3 (7.5) | 2 (5) | 5 (3) | 1 (10) | 0.011 |

| No | 43 (86) | 97 (79.5) | 34 (85) | 36 (90) | 153 (95.5) | 8 (80) | |

| Do not know | 2 (4) | 16 (13.1) | 3 (7.5) | 2 (5) | 2 (1.5) | 1 (10) | |

| Q5. Have you heard about the World Glaucoma Week celebration? | |||||||

| Yes | 30 (60) | 15 (12.5) | 27 (67.5) | 26 (65) | 104 (64.5) | 8 (80) | < 0.0011 |

| No | 20 (40) | 105 (87.5) | 13 (32.5) | 14 (35) | 55 (35.5) | 2 (20) | |

In the attitude-based questionnaire, very few participants (11.1%) considered cataracts and glaucoma to be the same. Most participants were well aware of the risk factors for glaucoma. Almost all participants in the consultant group (100%) knew that early blindness from glaucoma was preventable. Most nursing staff (84.4%) knew that peripheral vision loss occurs in patients with glaucoma. Most of the participants were aware of the increased IOP associated with glaucoma. Overall, there were various responses in a part of the eye affected in patients with glaucoma. Nearly 48% of participants were aware of the familial predisposition of glaucoma. Among the participants, 51% were aware of the irreversible damage. In the treatment of glaucoma, only 11% of participants were mindful of device implant surgeries and laser treatment (32%), and 6% were not aware of any of the treatment modalities. Approximately 42% of the participants were aware of the lifelong requirements of medications and treatment. Thirty-nine percent of the participants reported that eye donation is required to treat glaucoma. Regarding glaucoma treatment, 76% answered that it would restore vision and delay progression (39%) (Table 3).

| Nursing students | MBBS students | Resident doctors | Consultants (n = 40) | Nursing staff (n = 161) | Paramedical staff (n = 10) | P value | |

| Q1. Glaucoma and cataracts are the same. | |||||||

| Yes | 3 (6) | 0 | 1 (2.5) | 0 | 5 (3.1) | 0 | < 0.011 |

| No | 46 (92) | 104 (85.2) | 37 (92.5) | 40 (100) | 155 (96.2) | 9 (90) | |

| Do not know | 1 (2) | 18 (14.8) | 2 (5) | 0 | 1 (0.6) | 1 (10) | |

| Q2. Glaucoma occurs without symptoms. | |||||||

| Yes | 8 (16) | 20 (16.4) | 25 (62.5) | 26 (65) | 45 (27.9) | 1 (10) | < 0.011 |

| No | 38 (76) | 48 (39.3) | 13 (32.5) | 14 (35) | 113 (70.1) | 7 (70) | |

| Do not know | 4 (8) | 54 (44.3) | 2 (5) | 0 | 3 (1.8) | 2 (20) | |

| Q3. Risk factors for glaucoma. | |||||||

| High BP | 18 (36) | 53 (42.5) | 20 (50) | 10 (25) | 87 (54) | 1 (10) | < 0.011 |

| Old age | 26 (52) | 31 (24.7) | 18 (45) | 9 (22.5) | 82 (50.9) | 4 (40) | |

| Family history | 13 (26) | 25 (21.5) | 25 (62.5) | 8 (20) | 40 (24.8) | 4 (40) | |

| Steroid use | 7 (14) | 6 (4.7) | 21 (52.5) | 21 (52.5) | 23 (14.2) | 0 | |

| Do not know | 0 | 18 (14.8) | 3 (7.5) | 4 (10) | 4 (2.4) | 1 (10) | |

| Q4. Early blindness from glaucoma is preventable. | |||||||

| Yes | 38 (76) | 65 (53.3) | 37 (92.5) | 40 (100) | 140 (86.9) | 9 (90) | < 0.011 |

| No | 8 (16) | 10 (8.2) | 0 | 0 | 10 (6.2) | 1 (10) | |

| Do not know | 4 (8) | 47 (36.9) | 3 (7.5) | 0 | 11 (6.8) | 0 | |

| Q5. Peripheral vision loss occurs in glaucoma. | |||||||

| Yes | 35 (70) | 67 (54.9) | 32 (80) | 27 (67.5) | 136 (84.4) | 7 (70) | < 0.011 |

| No | 8 (16) | 6 (4.9) | 3 (7.5) | 2 (5) | 10 (6.2) | 3 (30) | |

| Do not know | 7 (14) | 49 (40.2) | 5 (12.5) | 11 (27.5) | 15 (9.3) | 0 | |

| Q6. What happens to eye pressure in glaucoma? | |||||||

| Increases | 44 (88) | 98 (80.3) | 37 (92.5) | 40 (100) | 158 (98.1) | 8 (80) | < 0.011 |

| Decreases | 2 (4) | 4 (3.3) | 1 (2.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Do not know | 4 (8) | 20 (16.3) | 2 (5) | 0 | 3 (1.8) | 2 (20) | |

| Q7. Which part of the eye is affected? | |||||||

| Cornea | 11 (22) | 22 (17.1) | 6 (15) | 6 (15) | 33 (20.4) | 6 (60) | < 0.011 |

| Lens | 12 (24) | 29 (22.6) | 2 (5) | 0 | 31 (19.2) | 5 (50) | |

| Retina | 8 (16) | 34 (27.8) | 11 (27.5) | 22 (55) | 45 (27.9) | 3 (30) | |

| Optic nerve | 29 (48) | 51 (41.7) | 36 (90) | 24 (60) | 113 (70.1) | 8 (80) | |

| Others | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.2) | 0 | |

| None | 2 (4) | 17 (13.9) | 2 (5) | 2 (5) | 2 (1.2) | 0 | |

| Q8. If glaucoma is present in your family, can you develop it? | |||||||

| Yes | 31 (62) | 39 (32) | 34 (85) | 25 (62.5) | 69 (42.8) | 6 (60) | < 0.011 |

| No | 14 (28) | 28 (23) | 3 (7.5) | 3 (7.5) | 75 (46.5) | 3 (30) | |

| Do not know | 5 (10) | 55 (44) | 3 (7.5) | 12 (30) | 17 (10.5) | 1 (10) | |

| Q9.Vision loss in glaucoma. | |||||||

| Reversible | 11 (22) | 18 (14.8) | 7 (17.5) | 6 (15) | 44 (27.3) | 3 (30) | < 0.011 |

| Irreversible | 33 (66) | 58 (47.5) | 25 (62.5) | 30 (75) | 96 (59.6) | 6 (60) | |

| Don’t know | 6 (12) | 46 (37.7) | 8 (20) | 4 (10) | 21 (13) | 1 (10) | |

| Q10. Is a person with diabetes or hypertension at risk of glaucoma? | |||||||

| Yes | 41 (82) | 71 (58.2) | 36 (90) | 31 (77.5) | 154 (95.6) | 8 (80) | < 0.011 |

| No | 5 (10) | 4 (3.3) | 0 | 0 | 3 (1.8) | 1 (10) | |

| Don’t know | 4 (8) | 47 (38.5) | 4 (10) | 9 (22.5) | 5 (3.1) | 1 (10) | |

| Q11. Is glaucoma treatable? | |||||||

| Yes | 39 (78) | 65 (53.3) | 37 (92.5) | 38 (95) | 149 (92.5) | 7 (70) | < 0.011 |

| No | 7 (14) | 17 (13.9) | 1 (2.5) | 2 (5) | 8 (4.9) | 2 (20) | |

| Do not know | 4 (8) | 37 (30.3) | 2 (5) | 0 | 4 (2.4) | 1 (10) | |

| Q12. What treatments are available? | |||||||

| Eyedrops | 28 (56) | 66 (53) | 30 (75) | 33 (82.5) | 107 (66.4) | 7 (70) | < 0.011 |

| Tablets | 14 (26) | 13 (10.5) | 23 (57.5) | 11 (27.5) | 49 (30.3) | 3 (30) | |

| Laser | 13 (26) | 33 (26.9) | 25 (62.5) | 12 (30) | 49 (30.3) | 4 (40) | |

| Surgery | 36 (72) | 64 (51) | 32 (80) | 14 (35) | 140 (86.9) | 8 (80) | |

| Device implant | 1 (2) | 5 (4) | 23 (57.5) | 0 | 20 (12.4) | 0 | |

| Others | 2 (4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.6) | 0 | |

| None | 2 (4) | 20 (16.4) | 2 (5) | 0 | 1 (0.6) | 1 (10) | |

| Q13. Treatment is lifelong. | |||||||

| Yes | 20 (40) | 31 (25.4) | 19 (47.5) | 13 (32.5) | 87 (54.0) | 7 (70) | < 0.011 |

| No | 17 (34) | 22 (18) | 10 (25) | 17 (42.5) | 53 (32.9) | 2 (20) | |

| Do not know | 13 (26) | 69 (54.9) | 11 (27.5) | 10 (25) | 21 (13.0) | 1 (10) | |

| Q14. It can be treated by eye donation. | |||||||

| Yes | 25 (50) | 27 (22.1) | 6 (15) | 11 (27.5) | 38 (23.6) | 6 (60) | < 0.011 |

| No | 15 (30) | 34 (27.9) | 25 (62.5) | 21 (52.5) | 86 (53.4) | 1 (10) | |

| Do not know | 10 (20) | 61 (47.5) | 9 (22.5) | 8 (20) | 37 (22.9) | 3 (30) | |

| Q15. Purpose of treatment in glaucoma. | |||||||

| Restore vision | 32 (64) | 39 (31.9) | 16 (40) | 22 (55) | 103 (63.9) | 4 (40) | < 0.011 |

| Delay progression | 16 (32) | 46 (37.7) | 28 (70) | 19 (47.5) | 51 (31.6) | 6 (60) | |

| Do not know | 2 (4) | 37 (30.1) | 3 (7.5) | 3 (7.5) | 7 (4.3) | 0 | |

Among the participants, 16% had never undergone ophthalmological evaluation. Nearly 52% of the participants had visited an ophthalmologist in less than 1 year, and 47% strongly agree with routine yearly eye checkups. If the participants were diagnosed with glaucoma, 81% wanted to proceed with surgical treatment, and 17% preferred medical treatment. Only 14% of the participants had previously participated in glaucoma seminars, and 94% of the participants were in favor of awareness programs such as seminars (22%), regular TV (26%), regular FM (radio) (8%), articles (10%), brochures (8%), and all of these (54%) (Table 4).

| Nursing students (n = 50) | MBBS students (n = 122) | Resident doctors (n = 40) | Consultants (n = 40) | Nursing staff (n = 161) | Paramedical staff (n = 10) | P value | |

| Q1. When did you last visit an ophthalmologist? | |||||||

| < 1 year | 26 (52) | 78 (64.7) | 22 (55) | 23 (57.5) | 65 (40.3) | 7 (70) | < 0.011 |

| 1-2 years | 14 (28) | 14 (12.4) | 8 (20) | 13 (32.5) | 21 (13.0) | 2 (2) | |

| > 3 years | 3 (6) | 10 (8.2) | 5 (12.5) | 4 (10) | 29 (18) | 1 (10) | |

| Never | 7 (14) | 13 (10.7) | 5 (12.5) | 0 | 46 (28.5) | 0 | |

| Q2. Are you in favor of routine yearly eye checkups? | |||||||

| Strongly agree | 28 (56) | 47 (38.5%) | 22 (55%) | 40 (100%) | 57 (35.4) | 5 (50) | < 0.011 |

| Agree | 18 (36) | 56 (45.9) | 16 (40) | 0 | 93 (57.5) | 4 (40) | |

| Neutral | 3 (6) | 13 (10.7) | 4 (10) | 0 | 9 (5.5) | 1 (10) | |

| Disagree | 1 (2) | 3 (2.5) | 3 (7.5) | 0 | 2 (12) | 0 | |

| Strongly disagree | 0 | 3 (2.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Q3. If you were diagnosed with glaucoma, would you agree to treatment? | |||||||

| Visit your ophthalmologist regularly and take the suggested treatment | 43 (86) | 93 (76.2) | 28 (70) | 36 (90) | 134 (83.2) | 9 (90) | 0.021 |

| Might miss one or two doses | 3 (6) | 2 (1.6) | 5 (12.5) | 0 | 4 (2.4) | 0 | |

| Will prefer getting glaucoma surgery | 4 (8) | 27 (22.1) | 7 (17.5) | 4 (10) | 27 (16.7) | 1 (10) | |

| Q4. If surgery was the only treatment option available, what would you do? | |||||||

| Will promptly go ahead with the surgery | 41 (82) | 82 (67.2) | 36 (90) | 20 (50) | 138 (85.7) | 10 (100) | < 0.011 |

| Try to defer surgery and continue eye drops | 7 (14) | 29 (23.8) | 1 (2.5) | 20 (50) | 15 (9.3) | 0 | |

| Take eyedrops and start alternatives like Ayurveda | 2 (4) | 11 (9) | 3 (7.5) | 0 | 3 (1.8) | 0 | |

| Q5. Have you attended any seminars or symposiums on glaucoma? | |||||||

| Yes | 12 (24) | 11 (9) | 6 (15) | 9 (22.5) | 20 (12.4) | 3 (30) | 0.0471 |

| No | 38 (76) | 111 (91) | 34 (85) | 31 (77.5) | 141 (87.5) | 7 (70) | |

| Q6. Will you support the glaucoma awareness program and camps? | |||||||

| Strongly agree | 27 (54) | 68 (55.7) | 24 (60) | 34 (85) | 93 (57.7) | 5 (50) | 0.021 |

| Agree | 21 (42) | 42 (34.4) | 15 (37.5) | 4 (10) | 64 (39.7) | 4 (40) | |

| Neutral | 2 (4) | 10 (8.2) | 1 (2.5) | 0 | 4 (2.4) | 1 (10) | |

| Disagree | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Strongly disagree | 0 | 2 (1.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Q7. Which type of awareness program do you think will reach more people and be more informative? | |||||||

| Seminars | 10 (20) | 28 (22.9) | 5 (5) | 8 (20) | 42 (26.1) | 4 (40) | < 0.011 |

| Regular TV | 11 (22) | 32 (26.1) | 15 (37.5) | 8 (20) | 43 (26.7) | 3 (30) | |

| Regular FM | 2 (4) | 6 (4.8) | 9 (22.5) | 10 (25) | 8 (4.9) | 1 (10) | |

| Article | 3 (6) | 20 (16.4) | 10 (25) | 2 (5) | 8 (4.9) | 1 (10) | |

| Brochure | 3 (6) | 13 (7.2) | 0 | 2 (5) | 17 (10.5) | 1 (10) | |

| Others | 3 (6) | 2 (1.6) | 0 | 0 | 4 (2.4) | 0 | |

| All of the above | 28 (56) | 66 (53.1) | 19 (47.5) | 18 (45) | 95 (59) | 4 (40) | |

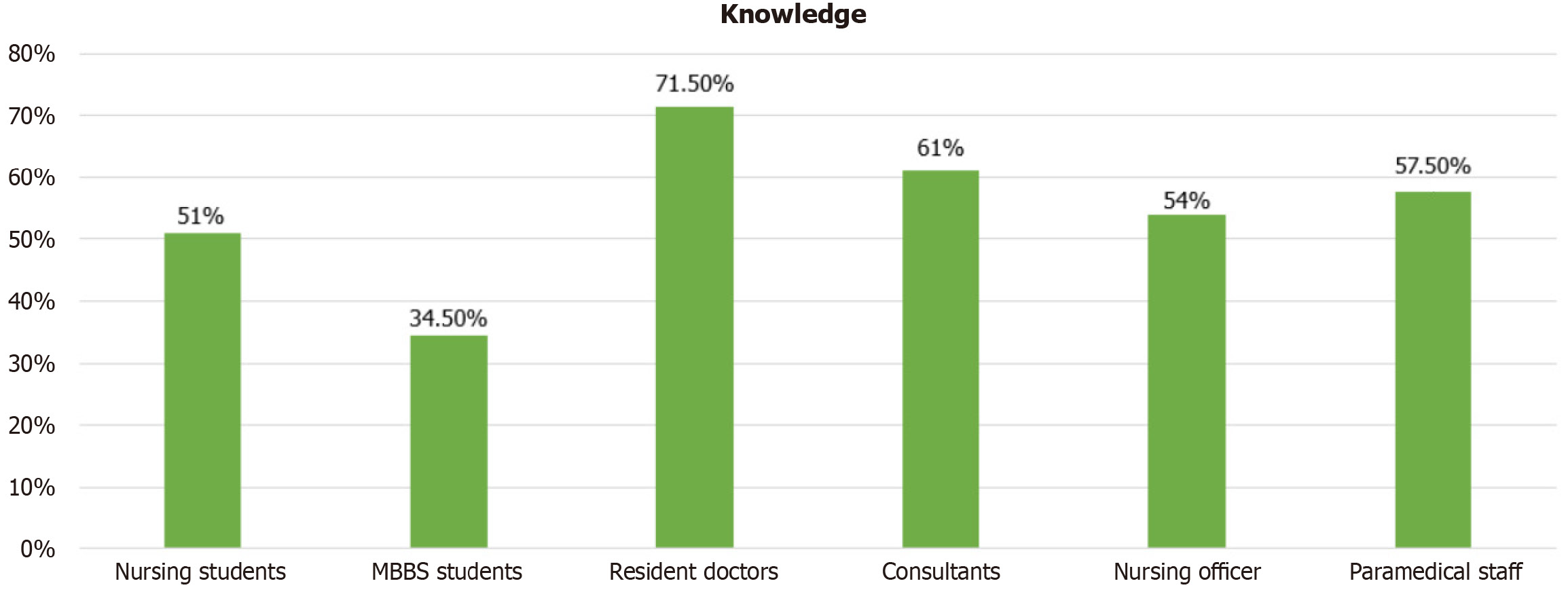

Analysis of the knowledge-based responses of the various participants revealed that the resident doctor group had more knowledge (71.50%) than the other groups. The consultant group had the second highest percentage (61%), and the MBBS group had the lowest percentage (34.50%) (Figure 1).

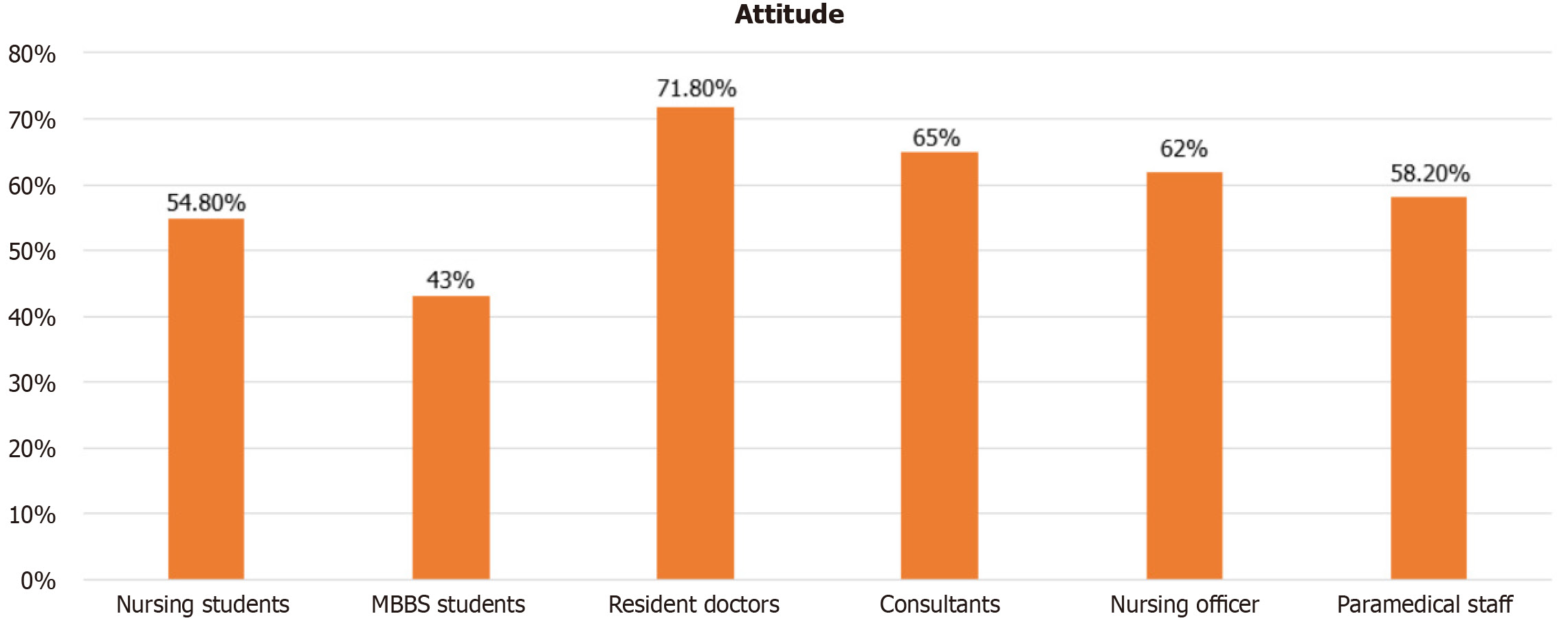

According to the results of the attitude questionnaire, approximately 71.80% of the resident doctors responded well, 65% of the consultant group responded the least, and 43% of the MBBS students responded the least (Figure 2).

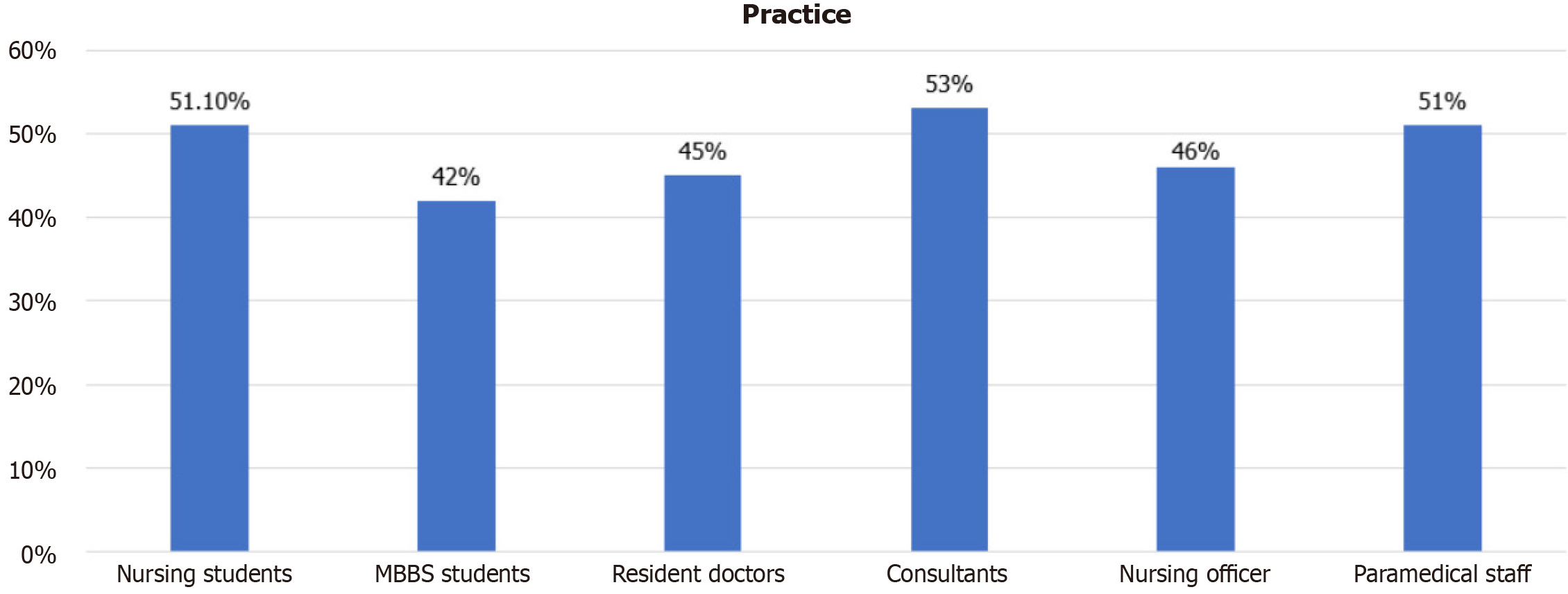

Analysis of the practice-based questionnaires among all the participants showed that the consultant group (53%) responded better than the resident doctors (45%), nursing officers (46%), and MBBS students (42%) (Figure 3).

In our study, there were 423 participants with a male:female ratio of 1:1.3, which correlates with the findings of a previous study by Amedome et al[3] that reported a similar proportion (1:1.04). Nevertheless, a study by Ichhpujani et al[2] reported a proportion of healthcare professionals of 1:2.5. The majority of studies involving healthcare workers reported that more than 90% of participants were aware of glaucoma [our study (95.2%) vs Ichhpujani et al[2] (100%) vs Amedome et al[3] (98.2%) vs Komolafeet et al[4] (100%)]. Nearly 56.2% of the participants in this study mentioned that they gained their glaucoma knowledge during medical training, whereas Ichhpujani et al[2] reported 78.9% (56.2% vs 78.9%).

Although the participants belonged to the medical community, 19 (4.8%) had not heard about glaucoma; however, a previous survey among healthcare professionals reported that more than 98% knew about glaucoma. Among the remaining participants who had heard about glaucoma, 26 (6%) participants did not know whether their family members were affected by it. In this study, 219 (51.7%) participants did not know the familial predisposition of the disease, and 71 (16.7%) had never had an ophthalmological evaluation. However, almost 91.2% of the participants opted for routine eye checkups. Twenty-three (5%) participants did not know that cataracts and glaucoma are separate entities, although a few had heard about glaucoma. Regarding the responses to the treatment-related questionnaires, 246 (58.1%) participants did not know about lifelong medication requirements such as those for systemic diseases. Although early diagnosis and treatment can prevent vision loss in these patients, 94 (22.2%) did not know about the early prevention of vision loss in patients with glaucoma. In addition, some of the participants had misinformation regarding eye donation, and 113 (26.71%) participants considered eye donation as a part of treatment. Half of the participants were unaware of the permanent vision damage associated with glaucoma, and 216 (51%) participants responded that therapy is intended to restore vision. In the advanced disease stage, when surgery is the only option, 17% of participants still preferred to continue with medication rather than surgery, and 4% opted for an alternative such as Ayurveda therapy.

The participants’ responses to the practice pattern questionnaires were quite enthusiastic. Approximately 48.9% of the participants had not heard about World Glaucoma Week celebration, 85.5% had not attended any symposiums or seminars, 94.7% strongly supported glaucoma awareness programs, and 91.2% strongly agreed with routine eye checkups.

In a survey conducted in the rural population of North India, higher educational status, employed participants, and annual eye checkups were significantly positively associated with awareness of glaucoma[10]. Healthcare professionals are responsible for educating the public. A survey of Southeast Nigerian patients with diagnosed glaucoma (n = 95) reported that 68.5% did not know about familial predispositions and that 87% had poor attitudes[11]. Another survey among Southwest Nigerian people (n = 259) revealed that only 41 (15.8%) had heard about glaucoma, 21 (51.2%) of whom were physicians[12]. In our study, the source of information was medical training for almost 56% of the participants, followed by physician visits for 26% of the participants, similar to a previous study by Prabhu et al[13], in which physicians were the significant sources of information. In addition to physicians, nursing healthcare professionals also play a significant role in awareness campaigns. Even though all participants in our study had heard about glaucoma, their overall knowledge (51% and 54%), attitudes (54.8% and 58.2%), and practices (51.1% and 51%) were fair among the nursing students and nursing staff, similar to the findings of a study by Shetty et al[14], which was conducted among nursing students in their final year. A survey by Ogbonnaya et al[15] in a rural Nigerian community revealed that the majority of participants (78.9%) had never heard of glaucoma, and those who heard about it received information from mass media. Hence, healthcare professionals must educate people about this vision-threatening condition via health campaigns. A survey of the North Indian population (n = 5000) by Rewri et al[16] revealed that only 409 (8.3%) patients were aware of glaucoma.

The limitation of this study was that only a few paramedical staff (lab technicians and occupational therapy technicians) were included. This was a cross-sectional study conducted at only one center in Eastern India, and almost one-third (n = 122, 28.8%) of the participants were MBBS students, which might have caused bias in the response.

Several studies have shown poor knowledge, attitudes, and practices toward glaucoma disease among the general population and even in patients with glaucoma. Healthcare professionals must educate the general public regarding the symptoms and signs of glaucoma. Not only ophthalmologists but also general physicians, nursing staff, and other healthcare workers can inform the public about glaucoma. Although less than half (49.6%) of our study population were aware of the World Glaucoma Week celebration, the majority (94.7%) strongly favored glaucoma awareness programs, and 91.2% opted for regular eye checkups. Ophthalmic healthcare workers can spread awareness about vision-threatening conditions among healthcare professionals and the community by utilizing awareness programs and screening campaigns. For example, programs such as the World Glaucoma Week celebration, which is held worldwide in the second week of March every year, should be expanded to increase awareness among the public and healthcare workers.

| 1. | Alemu DS, Gudeta AD, Gebreselassie KL. Awareness and knowledge of glaucoma and associated factors among adults: a cross-sectional study in Gondar Town, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Ophthalmol. 2017;17:154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ichhpujani P, Bhartiya S, Kataria M, Topiwala P. Knowledge, Attitudes and Self-care Practices associated with Glaucoma among Hospital Personnel in a Tertiary Care Center in North India. J Curr Glaucoma Pract. 2012;6:108-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Amedome MK, Mensah YAP, Vonor K, Maneh N, Dzidzinyo K, Saa KBN, Ayena KD, Balo K. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of Health Care Staff about Glaucoma in Lomé. OJOph. 2021;11:163-175. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Komolafe OO, Omolase CO, Bekibele CO, Ogunleye OA, Komolafe OA, Omotayo FO. Awareness and knowledge of glaucoma among workers in a Nigerian tertiary health care institution. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2013;20:163-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sanjana EF, Philip S, Ram V KS. Knowledge, attitudes, practices and quality of life assessment in glaucoma: a cross-sectional survey. Int J Med Res Rev. 2016;4:2199-2204. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Quigley HA, Broman AT. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:262-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4855] [Cited by in RCA: 5077] [Article Influence: 253.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Tham YC, Li X, Wong TY, Quigley HA, Aung T, Cheng CY. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:2081-2090. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5390] [Cited by in RCA: 4859] [Article Influence: 404.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 8. | Nkum G, Lartey S, Frimpong C, Micah F, Nkum B. Awareness and Knowledge of Glaucoma Among Adult Patients at the Eye Clinic of a Teaching Hospital. Ghana Med J. 2015;49:195-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Olawoye O, Fawole OI, Monye HI, Ashaye A. Eye Care Practices, Knowledge, and Attitude of Glaucoma Patients at Community Eye Outreach Screening in Nigeria. J West Afr Coll Surg. 2020;10:16-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Paul S, Verama K, Mehra S, Prajapati P, Sidhu T, Malhotra V. Knowledge and awareness about glaucoma and its determinants: A lesson learned from a community-based survey of a developing nation. J Health Res Rev. 2020;7:10. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Achigbu E, Chuka-okosa C, Achigbu K. The knowledge, perception, and attitude of patients living with glaucoma and attending the eye clinic of a secondary health care facility in Southeast Nigeria. Niger J Ophthalmol. 2015;23:1. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Isawumi MA, Hassan MB, Akinwusi PO, Adebimpe OW, Asekun-Olarinmoye EO, Christopher AC, Adewole TA. Awareness of and Attitude toward glaucoma among an adult rural population of Osun State, Southwest Nigeria. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2014;21:165-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Prabhu M, Patil S, Kangokar PC. Glaucoma awareness and knowledge in a tertiary care hospital in a tier-2 city in South India. J Sci Soc. 2013;40:3. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Shetty NK, Umarani R. Glaucoma awareness among the final year nursing students. IJCEO. 2019;5:71-77. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Ogbonnaya CE, Ogbonnaya LU, Okoye O, Kizor-akaraiwe N. Glaucoma Awareness and Knowledge, and Attitude to Screening, in a Rural Community in Ebonyi State, Nigeria. OJOph. 2016;06:119-127. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rewri P, Kakkar M. Awareness, knowledge, and practice: a survey of glaucoma in north Indian rural residents. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2014;62:482-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/