Published online Dec 20, 2025. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v15.i4.102894

Revised: March 13, 2025

Accepted: April 3, 2025

Published online: December 20, 2025

Processing time: 276 Days and 18.6 Hours

Outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT) offers a crucial method for administering intravenous/intramuscular antimicrobials outside of hospital settings, allowing patients to complete treatment safely while avoiding many hospital-acquired complications. This is a major boost or low-hanging fruit in

To evaluate the effectiveness, safety, and feasibility along with barriers and facilitators of OPAT practices in resource-poor settings, with a focus on its role in antimicrobial stewardship.

This pilot longitudinal observational study included patients who met OPAT checklist criteria and were committed to post-discharge follow-up. Pre-discharge education and counselling were provided, and demographic data were recorded. Various outcome measures, including barriers and facilitators, were identified through an extensive literature review, fishbone diagram preparation, data collection and analysis, and patient feedback. All healthcare workers who were taking care of the patients discharged with OPAT were contacted with open-ended questions to get data on feasibility. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh. We used descriptive analysis and the χ2 test to analyze data. P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Out of 20 patients, the mean age was 37 years. The cohort comprised 13 males. OPAT was administered at home in 15 cases and at nursing homes in 5 cases, with nine patients receiving treatment from family members and 11 patients receiving care from a local nurse. The infections requiring OPAT included: Kidney-urinary tract (6 cases), gastrointestinal tract (4 cases), respiratory tract (4 cases), meningitis (3 cases), endocarditis (2 cases), and multiple visceral abscesses (1 case). Nineteen out of 20 patients achieved afebrile status. Half of the patients did not receive education, counselling, or demonstrations prior to discharge, but all patients rated the service as good/excellent. According to doctors’ feedback, OPAT is highly beneficial and effective for patients when systematically implemented with daily telephonic monitoring, but faces challenges due to the lack of standardized protocols, dedicated teams, and adequate resources. The implementation of OPAT resulted in a reduction of hospitalization duration by an average of two weeks.

This pilot study proves that OPAT is safe, feasible, and efficacious by reducing two weeks of hospitalization in resource-poor settings. OPAT contributes directly to antimicrobial stewardship by reducing hospital stays and hospital-acquired complications, which is vital in combating antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and aligns with the global action plan for AMR in infection prevention and optimal antimicrobial utilization.

Core Tip: There is a lack of knowledge about the outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT) practice among healthcare workers (HCWs), including those working in tertiary care settings. To improve the quality of OPAT practice, systematic implementation of standardized protocols, dedicated teams, and comprehensive pre-discharge education for patients and caregivers is essential. Enhancing these elements can further bolster antimicrobial stewardship and contribute to global efforts against antimicrobial resistance. This can be done by organizing training sessions for all HCWs involved in patient care.

- Citation: Kumar A, Panda PK. Effectiveness, safety, and feasibility of outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy in a resource-limited setting: A pilot longitudinal study. World J Methodol 2025; 15(4): 102894

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v15/i4/102894.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v15.i4.102894

Outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT) has become essential in the continuum of care for patients requiring long-term antimicrobial therapy outside hospital settings. Its implementation is critical in reducing hospital admissions, lowering healthcare costs, and minimising the risks associated with prolonged hospital stays, such as nosocomial infections[1]. However, more extensive research is needed to fully understand the economic analysis of OPAT in re

Financial constraints also present significant challenges. The cost of antimicrobial agents, infusion equipment, and the need for frequent monitoring can be prohibitive, especially in low-resource settings[9]. Moreover, the reimbursement policies for OPAT services vary widely across regions, often discouraging healthcare providers from offering these services[10]. Patient-related factors, such as adherence challenges due to lacking transportation, forgetting appointments and storing medications out of the recommended range temperature, safety concerns, logistical issues related to home-based care, and the psychological burden of managing complex treatments at home, also contribute to the barriers[11].

On the other hand, facilitators that can enhance the practice of OPAT include the development of multidisciplinary teams and robust communication channels among healthcare providers[12]. Advances in telemedicine and remote monitoring technologies have also emerged as crucial facilitators, allowing for real-time patient monitoring and timely interventions, thus improving patient outcomes and satisfaction[13]. Furthermore, educational initiatives aimed at both healthcare providers and patients have been shown to enhance adherence to OPAT protocols and optimize antimicrobial use[14]. Addressing these barriers and leveraging the facilitators are crucial steps in integrating OPAT into broader antimicrobial stewardship strategies, ultimately helping to curb the rise of AMR.

In a resource-restrained environment, there is no standard guideline to practice OPAT, hence it is not routinely practised due to the absence of health insurance coverage, lack of trained personnel and limited outpatient infrastructure. In India, the burden of infections and AMR is significant, with 297000 deaths attributable to AMR and 1042500 deaths associated with AMR in 2019. Previous studies on OPAT in resource-limited settings have not assessed long-term outcomes or patient safety in a longitudinal format. Additionally, OPAT has not been extensively tested in this particular context due to concerns regarding safety and feasibility. A pilot longitudinal observational study was conducted to gather preliminary data on the operational challenges and to assess the effectiveness, safety, and feasibility of OPAT, as well as to identify the barriers and facilitators in a resource-limited tertiary care hospital setting. Conducting a larger-scale study could overlook critical factors impacting the program’s success, without such data.

We conducted a pilot longitudinal observational study with above objectives at All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Rishikesh, India (a resource poor setting) between December 2023 and May 2024.

We recruited 20 patients who were administered OPAT from the Department of General Medicine, AIIMS Rishikesh. A predefined OPAT checklist was utilized to evaluate each patient’s eligibility for OPAT. Only those patients who met the criteria outlined in the OPAT checklist and demonstrated a willingness to adhere to a structured follow-up regimen post-discharge were discharged with OPAT recommendations. A total of 20 patients met these criteria and were included in the study. This method ensured that the study cohort consisted solely of patients deemed capable of effectively participating in the OPAT regimen.

The OPAT checklist used for patient selection was: (1) Patient does not require hospitalization for any intervention; (2) Patient is vitally stable or clinically improved to a state of discharge; (3) Patient is capable of safe and effective IV/IM drug administration at home; (4) Therapeutic monitoring is feasible over a phone/outpatient department (OPD) basis; (5) Drug storage is feasible in patient’s home; and (6) Patient is willing to start and participate in a sharing decision resulting in a signed (patient and doctor) page of this.

The study utilized various antimicrobial agents, with the selection of specific agents being determined by the type of infection and individual patient factors. Pre-discharge education and counselling were provided, and demographic details, including patient contact information, were recorded before discharge. Patients were advised to attend follow-up appointments at the OPD as directed by the treating physician and to maintain telephonic communication.

Daily monitoring of patients discharged with OPAT was conducted telephonically by the treating physician to assess effectiveness, safety, and feasibility. This monitoring included the following: (1) The primary setting where OPAT was administered (e.g., home, outpatient clinic, infusion centre, skilled nursing facility, or physician's office); (2) The individual responsible for administering OPAT (e.g., family members, local nurse, or physician); (3) Assessment of clinical improvements, specifically the resolution of primary symptoms; (4) Identification of any new symptoms; (5) Monitoring for adverse events related to the medication or vascular access, including adherence to the prescribed regimen, cannula changes every third day, or immediate replacement if complications such as swelling, redness at the cannula site, or fever with chills and rigor occurred; (6) Documentation of any premature cessation of OPAT administration and the reasons for such discontinuation; and (7) Close daily follow-up ensured that any complications or deviations from the treatment protocol were promptly addressed. Additionally, feedbacks from patients and HCWs were collected following the completion of the treatment course.

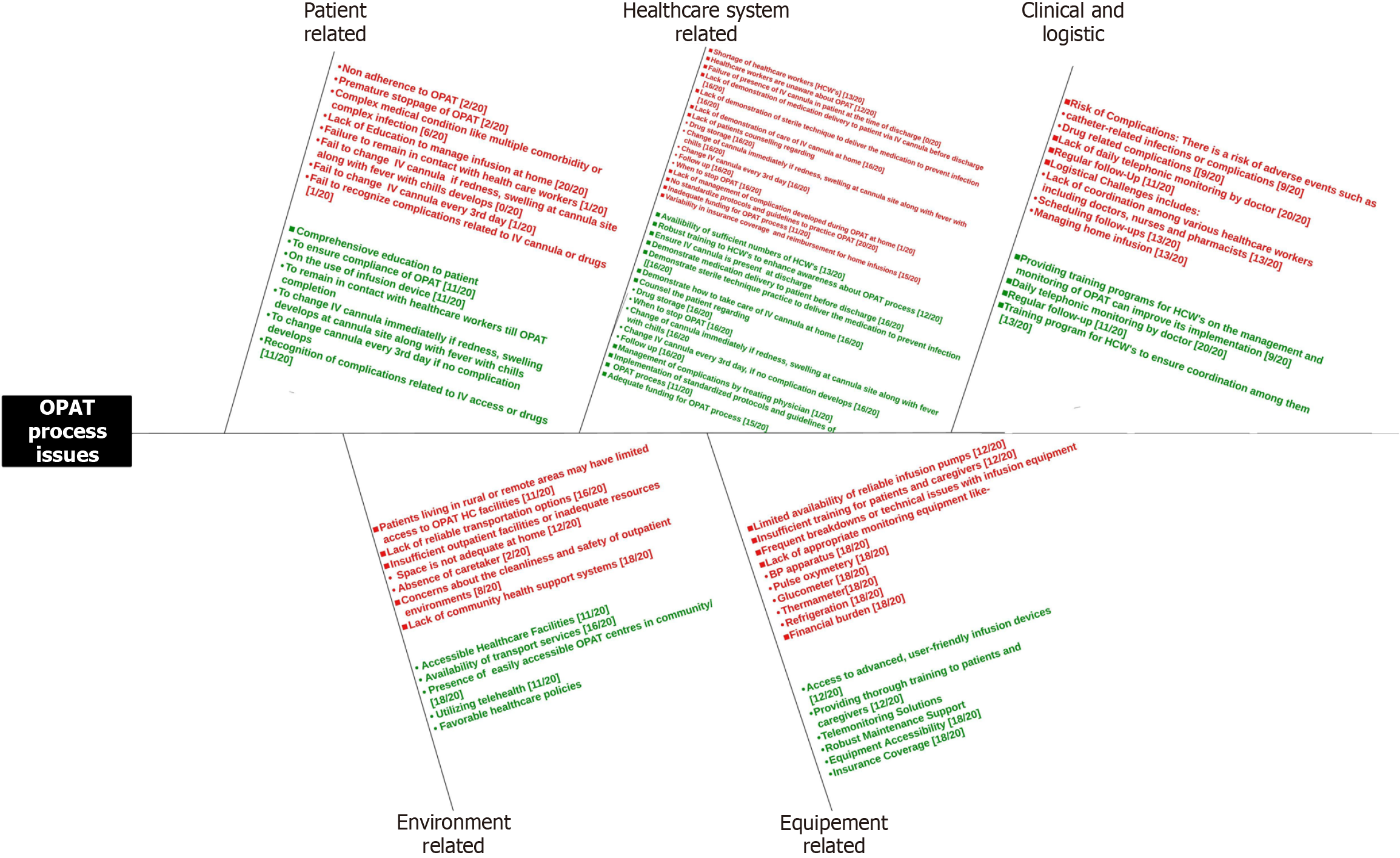

While practising the OPAT, many barriers and facilitators were observed and identified in the fishbone diagram, prepared after an extensive literature review and feedback from patients and HCWs (they were contacted with open-ended questions to get data on feasibility). Additional details, including the type of infection, the antimicrobial agent prescribed, and the corresponding dosage and duration, were obtained from patient records by accessing the Medical Records Department of the hospital.

We used descriptive analysis and the χ2 to analyze data. P value < 0.05 was considered significant. Descriptive statistics were employed to summarize patient demographics, clinical outcomes and gender distribution. Frequencies and percentages were used to categorize infections and antimicrobial agents administered. Patient outcomes were quantified and clinical improvement was tracked through follow-up data. Statistical comparisons were made regarding treatment duration. Barriers and facilitators identified through patient feedback were analyzed.

The approval to conduct this research was taken from the Institutional Ethics Committee of AIIMS, Rishikesh, India. To maintain privacy, any data that may have identified the individual participants of the study was not disclosed.

The majority of patients were middle-aged, with males constituting over 50% of the cohort (Table 1). OPAT was primarily administered in the home setting, and in more than half of the cases, local health nurses facilitated the treatment.

| Parameters | Value |

| Mean age | 37 years (age range = 21-63 year) |

| Gender distribution | |

| Male | 13 |

| Female | 7 |

| Site of OPAT administration | |

| Home | 15 |

| Nursing home | 5 |

| Administration method | |

| Administered by family members | 9 |

| Administered by local nurse | 11 |

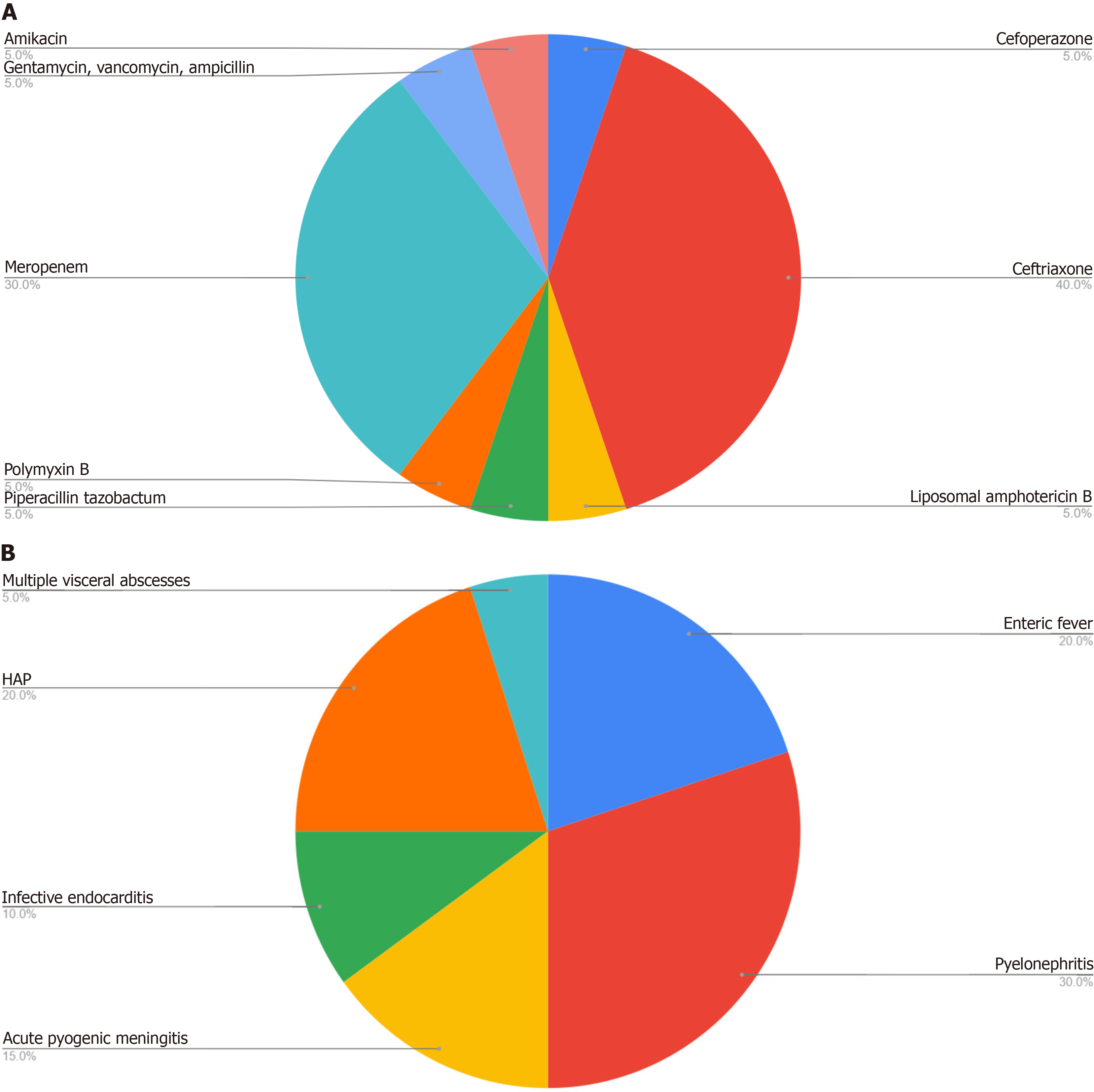

The majority of infections requiring OPAT were from kidney-urinary, gastrointestinal tract, or respiratory tracts (Figure 1A). All the patients achieved afebrile status. Two patients, with diagnosis of enteric fever, discontinued their OPAT regimens prematurely one after 6 days and the other after 8 days. Both patients demonstrated clinical improvement, with no fever spikes, and reported complete resolution of symptoms, including improved appetite and sleep. They remained afebrile throughout a 3-month follow-up period. One patient was readmitted due to the inability to administer OPAT at home because of the unavailability of the medication and a caregiver. This patient experienced fever for 4-5 days before receiving assistance from a local nurse. The patient subsequently became afebrile after 5-days. After 3-months of follow-up, he showed complete resolution of infection as confirmed by radiological and microbiological evaluations. Additionally, one patient developed thrombophlebitis. It was noted that approximately half of the patients did not receive education, counselling, or demonstrations before discharge. However, all patients rated the service as good/excellent and stated that they would choose the OPAT service again. The implementation of OPAT resulted in a reduction of hospitalization duration by an average of two weeks, thereby lowering hospitalization costs without compromising clinical efficacy.

Ceftriaxone was the most frequently prescribed antimicrobial, used in 8 of the 20 cases (Figure 1B). The average duration of OPAT was 14 days, with a range extending from 5 days to 6 weeks, the latter being for cases of fungal pyelonephritis.

Various barriers and facilitators were identified and represented in a fishbone diagram (Figure 2). Barriers to OPAT implementation included inadequate training of HCWs and communication gaps among them. The lack of standardized procedures also hampered effective OPAT processes. Equipment-related challenges involved non availability of equipment, lack of knowledge of their functioning and maintenance and insufficient storage for antimicrobials, while the home environment often lacked suitability for proper administration and care, including absence of caregiver, remote location and no accessibility to nearby OPAT centers. Facilitators included training programs for HCWs emphasizing on daily telephonic monitoring ensuring OPAT compliance and early identification of any complication and its ma

OPAT represents a significant advancement in healthcare delivery, particularly in resource-poor settings where hospital resources are limited and the burden of infectious diseases is high. Despite its potential to enhance patient care and reduce healthcare costs, the implementation of OPAT faces several challenges that need to be addressed to maximize its effectiveness. This discussion explores the key issues and considerations surrounding OPAT practice in such settings, focusing on patient adherence, healthcare infrastructure, financial implications, and its role in antimicrobial stewardship.

The findings of this pilot study offer significant insights into the role of OPAT as a 100% effective alternative for managing a variety of infections and its potential impact on healthcare resource utilisation. The study demonstrates that OPAT is a viable approach for treating a broad spectrum of infections, including complicated urinary tract infections, enteric fever, hospital-acquired pneumonia, acute pyogenic meningitis, infective endocarditis, and multiple visceral abscesses. In this study, a majority of patients (95%) exhibited clinical improvement and resolution of infections within two weeks, with a single case requiring one and a half months of follow-up for resolution. These results underscore the efficacy of OPAT in administering IV antimicrobials outside of acute care hospital settings. Hitchcock et al[15] report on a case series of 303 episodes of OPAT care, in a resource-rich setting. found readmission in 23 episodes (7.6%), and two patients lost vascular access, resulting in the early termination of OPAT. Of the remaining 273 episodes of care, over 95% of cases were resolved with a single course of antibiotics and few adverse events were reported. A series of 334 episodes of OPAT care was reported by Chapman et al[16]. A total of 87% of patients across all diagnoses were classified as improved or cured (92% when including skin and soft tissue infections only). Twenty-one patients (6.3%) were readmitted, although 12 of these were for reasons unrelated to OPAT. The group also looked to address the issue of patient satisfaction. Of 449 patients surveyed, 276 responded (61%). 272 (98.6%) rated the service as very good or excellent, and 275 (99.6%) stated that they would choose the OPAT service again[16]. In our study, there was 1 readmission (5%), 1 patient developed thrombophlebitis (5%) and 100% cases resolved after OPAT therapy. In resource-poor settings, a study in Japan similar to our study highlights a high cure rate and low readmission rate, which reflect careful patient selection, reduced hospitalization duration and saved bed days[2].

The safety profile of OPAT in this case series was favorable. A comprehensive monitoring and adverse event reporting system facilitated the prompt detection and management of complications, such as thrombophlebitis, which was effectively managed with topical Thrombophob ointment. Some of the unexpected findings emerging from this study include 100% safety and effective treatment, low readmission rate (one patient) and relatively low adverse event (one case of thrombophlebitis). The likely reason for this favorable outcome is robust daily monitoring by the treating physician, and almost all patients came for follow-up. This outcome aligns with the growing body of evidence supporting OPAT's safety, thereby providing reassurance to both healthcare providers and patients in resource-poor settings.

Adherence is critical for the success of OPAT, as incomplete or incorrect administration of antimicrobials can lead to treatment failure, relapse, or the development of AMR[17]. Factors influencing adherence include the complexity of the treatment regimen, the patient’s understanding of the therapy, and the support available from healthcare providers. In resource-poor settings, where access to healthcare professionals may be limited, ensuring adherence can be particularly challenging. Studies have shown that providing comprehensive education and counselling before discharge significantly improves adherence rates[18,19]. However, the pilot study indicates that nearly half of the patients did not receive adequate pre-discharge education, highlighting a critical gap in OPAT implementation that must be addressed to improve outcomes[20]. Beyond the lack of education, other patient related barriers affecting the OPAT adherence includes transportation difficulties, affordability of antibiotics and home hygiene challenges.

Healthcare infrastructure also plays a vital role in the successful implementation of OPAT. The availability of trained healthcare providers, such as nurses and pharmacists, who can administer and monitor therapy is essential. In many resource-poor settings, there is a shortage of such professionals, which limits the ability to deliver OPAT effectively[21]. Additionally, the lack of essential equipment, such as infusion pumps and telemedicine tools for remote monitoring, further complicates the delivery of OPAT. Innovative solutions, such as task-shifting and training community health workers to assist in OPAT, have shown promise in overcoming these barriers[22]. However, such interventions require careful planning and support from healthcare systems to be sustainable.

Financial considerations are another critical factor in OPAT practice. The cost of antimicrobials, particularly newer agents that are often required for resistant infections, can be prohibitive in resource-poor settings[23]. Furthermore, the costs associated with administering OPAT, including the need for frequent follow-up and monitoring, add to the financial burden on both healthcare systems and patients. In resource-poor setting, where healthcare resources are already limited, this financial burden may limit the patient’s access to the necessary treatment and can result in OPAT failure. The variability in reimbursement policies exacerbates these challenges. Ensuring that OPAT is financially accessible requires policy interventions that address these cost barriers, potentially through subsidies, insurance coverage, or other forms of financial assistance[24]. Furthermore, the involvement of public-private partnerships in enhancing the affordability of OPAT services could also play a crucial role in addressing these financial challenges associated with OPAT. Despite challenges in resource-poor settings, the long-term feasibility of OPAT can be enhanced through comprehensive pre-discharge education, daily monitoring, telemedicine, effective management of complications, and adequate financial and infrastructure support.

OPAT’s role in antimicrobial stewardship cannot be overstated. Since it was a pilot study, AMR monitoring was not done and it must be incorporated in future OPAT programs. In most cases, microbiological confirmation was not done, which is also crucial for antibiotic use optimization. By enabling the use of appropriate antimicrobials outside of hospital settings, OPAT reduces the risk of hospital-acquired infections and the subsequent need for broad-spectrum antibiotics, which are often overused in inpatient settings[25]. Furthermore, OPAT allows for the continuation of therapy with narrow-spectrum agents, aligning with the principles of antimicrobial stewardship by minimizing the selection pressure for resistant organisms[26]. The integration of OPAT into broader antimicrobial stewardship programs can help in optimizing antimicrobial use, reducing AMR rates, and ultimately improving patient outcomes. However, to achieve these benefits, OPAT programs must be carefully managed and supported by robust stewardship frameworks that include monitoring and feedback mechanisms[27]. At present, in India, OPAT is no where, but similar to any low-hanging fruits of stewardship practices such as ‘color-coded charts for antimicrobial prescriptions’ in a private hospital, this pilot project will go a long way[28].

OPAT can scale with the introduction of a reimbursement policy for all patients, provision of standard guidelines, training of HCWs, availability of ID physician improvements in infrastructure and patient access to medications. Governments should invest in training of HCWs, infrastructure building, medication access, and telemedicine for OPAT implementation. Furthermore, developing national guidelines will standardize OPAT care and address resource-limited setting challenges.

It's important to acknowledge the limitations of this study, including the relatively small sample size, selection bias, and the single-center nature of the study. Further research with a larger sample size and multi-centre studies is needed to validate these findings and explore the broader applicability of OPAT in different healthcare settings. As this is a pilot study, the potential for selection bias was minimised by systematically screening all patients receiving intravenous antimicrobials for OPAT eligibility using a prespecified checklist. Additionally, to make the OPAT more successful and adverse event-free, a dedicated and well-trained team of HCWs is needed as well proper funding should be provided.

The results of this pilot study substantiate the 100% efficacy of OPAT in the management of diverse infections, while concurrently reducing hospitalization duration and associated costs. With a 95% rate of clinical improvement and a 100% safety profile, OPAT presents a robust alternative to traditional inpatient care, particularly in resource-constrained environments like India. Nonetheless, the study highlights significant challenges, including patient adherence, deficiencies in healthcare infrastructure, and financial constraints. Notably, nearly 50% of patients received inadequate pre-discharge education, which may hinder treatment success and contribute to the development of AMR. Structured OPAT programs with dedicated teams, task-shifting models, long-term research on cost-effectiveness, AMR reduction, and patient outcomes are essential to make this model more successful and accessible in future.

We acknowledge the contributions of our mentors and colleagues whose insights and guidance significantly enriched this research. Our heartfelt thanks go to the study participants for their cooperation and contribution. Finally, we recognize the role of anonymous reviewers and prior researchers whose work laid the foundation for this study. Their collective efforts were instrumental in the successful completion of this work.

| 1. | Panda PK, Mathur A. Outpatient Antimicrobial Parenteral Therapy (OPAT) in Indian Setting-An Update. JASPI. 2024;2:1-4. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | Hase R, Yokoyama Y, Suzuki H, Uno S, Mikawa T, Suzuki D, Muranaka K, Hosokawa N. Review of the first comprehensive outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy program in a tertiary care hospital in Japan. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;95:210-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yadav K, Suh KN, Eagles D, Thiruganasambandamoorthy V, Wells GA, Stiell IG. Evaluation of an emergency department to outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy program for cellulitis. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37:2008-2014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rentala M, Andrews S, Tiberio A, Alagappan K, Tavdy T, Sheppard P, Silverman R. Intravenous Home Infusion Therapy Instituted From a 24-Hour Clinical Decision Unit For Patients With Cellulitis. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34:1273-1275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | White BP, Alkozah M, Siegrist EA. Time for OPAT coordination: difficult to quantify due to heterogeneity in OPAT care models. Clin Infect Dis. 2024;ciae415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Grabar S, Potard V, Piroth L, Abgrall S, Bernard L, Allavena C, Caby F, de Truchis P, Duvivier C, Enel P, Katlama C, Khuong MA, Launay O, Matheron S, Melica G, Melliez H, Meynard JL, Pavie J, Slama L, Bregigeon S, Tattevin P, Capeau J, Costagliola D. Striking differences in weight gain after cART initiation depending on early or advanced presentation: results from the ANRS CO4 FHDH cohort. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2023;78:757-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chukwu EE, Abuh D, Idigbe IE, Osuolale KA, Chuka-Ebene V, Awoderu O, Audu RA, Ogunsola FT. Implementation of antimicrobial stewardship programs: A study of prescribers' perspective of facilitators and barriers. PLoS One. 2024;19:e0297472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Canterino J, Malinis M, Liu J, Kashyap N, Brandt C, Justice A. Creation and Validation of an Automated Registry for Outpatient Parenteral Antibiotics. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2024;11:ofae004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Schranz AJ, Swartwood M, Ponder M, Boerneke R, Oosterwyk T, Perhac A, Farel CE, Kinlaw AC. Quantifying the Time to Administer Outpatient Parenteral Antimicrobial Therapy: A Missed Opportunity to Compensate for the Value of Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2024;79:348-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bianchini ML, Kenney RM, Lentz R, Zervos M, Malhotra M, Davis SL. Discharge Delays and Costs Associated With Outpatient Parenteral Antimicrobial Therapy for High-Priced Antibiotics. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:e88-e93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Harun MGD, Sumon SA, Hasan I, Akther FM, Islam MS, Anwar MMU. Barriers, facilitators, perceptions and impact of interventions in implementing antimicrobial stewardship programs in hospitals of low-middle and middle countries: a scoping review. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2024;13:8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Huai Luo C, Paul Morris C, Sachithanandham J, Amadi A, Gaston DC, Li M, Swanson NJ, Schwartz M, Klein EY, Pekosz A, Mostafa HH. Infection With the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Delta Variant Is Associated With Higher Recovery of Infectious Virus Compared to the Alpha Variant in Both Unvaccinated and Vaccinated Individuals. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;75:e715-e725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Snoswell CL, De Guzman K, Neil LJ, Isaacs T, Mendis R, Taylor ML, Ryan M. Synchronous telepharmacy models of care for adult outpatients: A systematic review. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2025;21:1-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Norris AH, Shrestha NK, Allison GM, Keller SC, Bhavan KP, Zurlo JJ, Hersh AL, Gorski LA, Bosso JA, Rathore MH, Arrieta A, Petrak RM, Shah A, Brown RB, Knight SL, Umscheid CA. 2018 Infectious Diseases Society of America Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Outpatient Parenteral Antimicrobial Therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68:1-4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hitchcock J, Jepson AP, Main J, Wickens HJ. Establishment of an outpatient and home parenteral antimicrobial therapy service at a London teaching hospital: a case series. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;64:630-634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chapman AL, Dixon S, Andrews D, Lillie PJ, Bazaz R, Patchett JD. Clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness of outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy (OPAT): a UK perspective. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;64:1316-1324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hamad Y, Dodda S, Frank A, Beggs J, Sleckman C, Kleinschmidt G, Lane MA, Burnett Y. Perspectives of Patients on Outpatient Parenteral Antimicrobial Therapy: Experiences and Adherence. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7:ofaa205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tice AD, Rehm SJ, Dalovisio JR, Bradley JS, Martinelli LP, Graham DR, Gainer RB, Kunkel MJ, Yancey RW, Williams DN; IDSA. Practice guidelines for outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy. IDSA guidelines. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:1651-1672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 393] [Cited by in RCA: 431] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Narayanan S, Ching PR, Traver EC, George N, Amoroso A, Kottilil S. Predictors of Nonadherence Among Patients With Infectious Complications of Substance Use Who Are Discharged on Parenteral Antimicrobial Therapy. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023;10:ofac633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Mehta M, Benning M, Johnson JE, Ryan KL. Facilitating OPAT in rural areas. Ther Adv Infect Dis. 2023;10:20499361231210353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Gilchrist M, Seaton RA. Outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy and antimicrobial stewardship: challenges and checklists. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:965-970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Seaton RA, Gilchrist M. Making a case for outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT). J Antimicrob Chemother. 2024;79:1723-1724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Krah NM, Bardsley T, Nelson R, Esquibel L, Crosby M, Byington CL, Pavia AT, Hersh AL. Economic Burden of Home Antimicrobial Therapy: OPAT Versus Oral Therapy. Hosp Pediatr. 2019;9:234-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Mansour O, Keller S, Katz M, Townsend JL. Outpatient Parenteral Antimicrobial Therapy in the Time of COVID-19: The Urgent Need for Better Insurance Coverage. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7:ofaa287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wolie ZT, Roberts JA, Gilchrist M, McCarthy K, Sime FB. Current practices and challenges of outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy: a narrative review. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2024;79:2083-2102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hassanzai M, Adanç F, Koch BCP, Verkaik NJ, van Oldenrijk J, de Bruin JL, de Winter BCM, van Onzenoort HAW. Best practices, implementation and challenges of outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy: results of a worldwide survey among healthcare providers. Ther Adv Infect Dis. 2023;10:20499361231214901. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Seaton RA, Barr DA. Outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy: principles and practice. Eur J Intern Med. 2013;24:617-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/