Published online Dec 20, 2025. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v15.i4.102758

Revised: February 26, 2025

Accepted: March 17, 2025

Published online: December 20, 2025

Processing time: 280 Days and 12.9 Hours

The prevalence of depressive symptoms in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty (TKA) ranges from 22% to 26%. The impact of depression on functional status post-TKA remains controversial.

To be the first study in Latin American population to evaluate the association between depression and functional status one year after TKA, hypothesizing that elderly patients with depression will demonstrate lower rates of functional improvement.

We conducted an observational, descriptive and analytic, retrospective cohort study involving patients over 65 years old who were indicated for TKA. Assessments were made via the Program for Determination and Management of Risks for Practices and Procedures of the Division of Geriatric Medicine at the Italian Hospital of Buenos Aires, between June 2015 and July 2019. Depression screening was conducted using Yesavage’s abbreviated score and Patient Health Questionnaire-9, while functional ability was evaluated using the Knee Society Score (KSS).

Of the 100 patients analyzed, 22 (22%) screened positive for depression. The mean age was 80 years ± 6.3 years, with an average of 77.6 years ± 6 years in the depressed group and 80.6 years ± 6.3 years in the non-depressed group (P = 0.05). Depressed patients showed significantly greater cognitive impairment [clock-face drawing test median: 5 (3-6) vs 6 (5-7), P = 0.06] and more risk factors for confusional syndrome (mean: 8 ± 2 vs 6.5 ± 2.2, P = 0.006). Frailty was also more prevalent in depressed patients [Edmonton: 15 (68%) vs 33 (42%), P = 0.05; Fried: 17 (77%) vs 42 (54%), P = 0.05]. Postoperative Functional KSS were similar between groups (depressed: 65 ± 22.1 vs non-depressed: 66.3 ± 20.3, P = 0.8). Linear regression analysis revealed no association between depression and changes in KSS. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were -0.0304 (P = 0.8) for Functional KSS variation and -0.1 (P = 0.3) for KSS variation.

Depression in patients with osteoarthritis should not hinder surgical planning. Identifying and treating depression preoperatively may enhance outcomes such as pain relief and reduce risks of acute confusional syndrome, cognitive impairment, and frailty.

Core Tip: This study evaluates the relationship between depression and functional outcomes one year after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in elderly patients. Results indicate that while depressive symptoms are common, they do not impact functional recovery as measured by the Knee Society Score. However, depression correlates with greater cognitive impairment, increased frailty, and higher risk of confusional syndrome. These findings suggest that depression should not be a barrier to TKA, though preoperative identification and management of depressive symptoms may improve postoperative quality of life and reduce complications.

- Citation: Nicolino TI, Smietniansky M, Boietti B, Garcia-Mansilla I, Carbo L, Martinez CB. Impact of depression on functional status in elderly patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty. World J Methodol 2025; 15(4): 102758

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v15/i4/102758.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v15.i4.102758

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is the standard of care for the relief of severe osteoarthritis-associated knee pain that is refractory to non-surgical treatments. This procedure is widely accepted and consolidated in the field of orthopedics. Although pain is influenced by multiple factors, mental health disorders are often present alongside pain and tend to be linked with poorer outcomes. The prevalence of depressive symptoms in patients undergoing TKA ranges between 22%-26%[1]. Over the past years, several authors have defined depression as an independent variable for the prediction of TKA postoperative outcomes in elderly patients. Nonetheless, other authors have reported that depression does not appear to hurt outcomes[2]. Research addressing the impact of depression on functional status in TKA is scarce.

We must consider that many patients undergoing knee arthroplasty present a condition of frailty in their baseline health status. Fragility, or frailty, is a clinical syndrome characterized by a decline in physiological reserve and increased vulnerability to stressors, often manifesting as weakness, weight loss, exhaustion, and reduced physical activity. In contrast, cognitive impairment refers specifically to a decline in cognitive functions such as memory, reasoning, and problem-solving abilities. While both conditions are associated with aging and can lead to increased health risks, frailty primarily affects physical health and resilience, whereas cognitive impairment impacts mental processes and daily functioning. Understanding these differences is crucial for developing appropriate interventions and support for affected individuals.

A recent study by Gebauer et al[3] found no link between depression and the timing of TKA. However, surgeons should still assess patients for depression and its symptoms, as it is a common comorbidity that could affect postoperative outcomes. An observational study from a Swedish registry involving 8745 patients found that both preoperative and postoperative patient-reported anxiety or depression heighten the risk of dissatisfaction after TKA, even when pain and function improve[4]. Ensuring patients receive appropriate treatment for depression may be crucial for achieving favorable surgical results. Patients with anxiety or depression may struggle to participate fully in rehabilitation and experience poorer outcomes in terms of pain and function. Consequently, it remains uncertain whether the risk of dissatisfaction in these patients is due to their worse pain and functional outcomes or if the anxiety or depression itself plays a significant role[5].

We performed an observational, descriptive, analytic, retrospective cohort study to study the association between depression and functional status one year after TKA in patients over 65 years of age. We hypothesized that elderly patients with depression would have lower rates of functional improvement after one year in comparison to patients without depression. The demographic characteristics and the presence of geriatric syndromes in our patient population were evaluated, as well as the association between depression and major complications or death at three months post-surgery.

We also aimed to explore the association between depression and length of hospital stay, readmission, number of required sessions of physical therapy, and consultations with the surgical team.

We included patients over 65 years of age with an indication for TKA that were assessed by the Program Determination and Management of Risks for Practices and Procedures (DRIPP) of the Division of Geriatric Medicine of the Hospital Italiano of Buenos Aires (HIBA) before surgery between June 2015 and July 2019. Patients were required to receive surgical treatment within three months of initial evaluation. A specific team of orthopedic surgeons from the Division of Arthroscopic Surgery and Knee Prosthetics of the Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology of the HIBA performed all surgeries.

Patients were excluded from the study if they were planning to undergo procedures requiring additional procedure to total knee prosthesis (osteotomy, extensor mechanism realignment, or osteosynthesis), knee revision surgery, simultaneous bilateral arthroplasty, or if the prespecified surgical team did not perform surgery.

The Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology performs a monthly average of 600 surgeries, many of them being complex procedures such as joint reconstruction, spine and oncologic surgery. The DRIPP program was developed within the Department of Geriatric Medicine, and through it, approximately 700 patients are assessed per year. Since its establishment in 2013, over 2500 patients have been evaluated in both outpatient and inpatient settings. Typically, DRIPP assessment consists of a comprehensive clinical and geriatric evaluation of patients undergoing intermediate or high-risk surgical procedures, as well as oncologic treatment regimens (chemotherapy, radiation, or high-cost biologic drugs and targeted therapies). Clinical comorbidities are included in the analysis, but the main scope of assessment is the detection, qualification, quantification, and management of each patient's biological and psychosocial risk. The program works in a transdisciplinary fashion to achieve effective communication, produce an impact on decision-making, enhance the process of informed consent, decrease morbidity and mortality as well as improve each patient's functionality outcomes and global quality of life. Every aspect of patient care is carefully documented and stored within a centralized digital registry that includes a unique medical record and history for everyone.

In this study, patients referred for DRIPP assessment presented at least one of the following criteria for geriatric vulnerability: (1) Polypharmacy (according to Beers’ criteria[6]; (2) Functional impairment (defined if the patient requires assistance to perform any of the following activities, including meal preparation and feeding, handling finances, taking medication, shopping for groceries, or travelling alone by any means of transport); (3) Nutritional risk (loss of more than 5% body weight over the past year); (4) General health status (2 or more hospital admissions over the past year); (5) Risk of cognitive impairment (difficulty in understanding medical indications); (6) More than two clinical comorbidities; and (7) Dementia or Parkinson's Disease.

The program entails the exploration of functional ability through the assessment of the following domains: (1) Basic activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living[7], evaluation of disease burden through Charlson’s comorbidity index, polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medication; (2) Gait alterations and sarcopenia, nutritional status by mini-nutritional assessment[8]; and (3) Frailty according to Edmonton[9] and Fried[10], as well as screening for cognitive impairment[11], risk factors for acute confusional syndrome and depression. Life expectancy is also estimated by use of the PROFUND[12], Lee et al[13] and Schonberg et al[14] scores.

Once the evaluation is complete, geriatric specialists design specific interventions based on the findings. Chronic medication is listed and reviewed, and potentially inappropriate medication is gradually tapered or suspended. Detection of chronic clinical comorbidities allows for patient optimization if necessary. Alcohol consumption is discouraged and smoking cessation counseling is provided as needed. Malnourished or at-risk patients receive nutritional consultation. Both patients and care providers receive recommendations for the prevention of falls. Patients with high fall risk or sarcopenia are referred to physical therapy for optimization prior to the planned intervention (prehabilitation). Another important aspect of DRIPP assessment is screening for social geriatric risk. Vulnerable patients with debilitated or fragmented social support networks are enrolled for long term clinical follow-up by specialists in geriatric medicine.

Concerning the main aim of this study, screening for depression was performed by using two scales: (1) Yesavage’s abbreviated score (used from 2013 through 2016); and (2) Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (used from 2017 to present). The PHQ-2 questionnaire comprises two specific questions that interrogate the presence of anhedonia and dysphoria, which are both diagnostic criteria for major depressive episodes. Positive answers have 96% sensitivity and 57% specificity for the diagnosis of depression. A negative answer to both questions proves depression to be very unlikely, with a probability index of 0.07 and a subsequent probability of 2%. In this study setting, we considered patients with two positive answers to be depressed[15].

Yesavage’s Geriatric Depression Scale is an instrument that is widely used for depression screening in patients over 65 years of age[16]. In 1986, Yesavage and Sheikh[17] proposed an abbreviated version of the original test, which is composed of 15 questions. It maintains the classic “yes or no” format, but has greater application feasibility. A score of 5 or more positive answers suggests the diagnosis of depression. Both the original and the abbreviated questionnaire discriminate between depressed and non-depressed patients with excellent correlation (r = 0.84, P < 0.001)[17].

Functional ability was assessed using the Knee Society Score (KSS)[18] which is divided into two components. The first component assesses the knee clinically through physical examination, and includes the evaluation of pain, stability and range of movement with a resulting score that ranges from 0 to 100, 0 being the lowest score and 100 the highest. The second component assesses the individual's functionality, with the same value range.

Information was extracted through manual revision of the electronic medical records of patients planning to undergo TKA who were referred for DRIPP assessment prior to surgery during the aforementioned period. All of the study data was handled with maximum confidentiality and patient anonymity was preserved in all cases. The obtained data was transferred to a numerically coded database which was later processed and analyzed. Access to the database was restricted to the study investigators.

Exposure variables (depression), result variables (Knee Society functionality scores and combined event of death or major complication at 3 months) and clinical baseline variables were operationalized (Table 1).

| Characteristic | With depression (n = 22) | Without depression (n = 78) | P value |

| Female sex | 14 (64) | 51 (65) | 0.9 |

| Age (years) | 77.6 ± 6 | 80.6 ± 6.3 | 0.05 |

| Body mass index | 31.4 ± 6.3 | 30.8 ± 4.7 | 0.6 |

| Charlson index (IQR) | 1 (0-1) | 1 (0-2) | 0.1 |

| Diabetes | 2 (9) | 14 (18) | 0.5 |

| Hypertension | 16 (73) | 70 (90) | 0.04 |

| Hypothyroidism | 2 (9) | 23 (29) | 0.06 |

| Number of medications used | 6.6 ± 3.5 | 7.6 ± 3.2 | 0.2 |

| Older Americans Resources and Services Social Resource Scale (IQR) | 1.5 (1-2) | 1 (1-2) | 0.3 |

| Use of antidepressant medication | 7 (32) | 20 (26) | 0.6 |

| Use of Potentially Inappropriate Medication (Beers Criteria) | 18 (82) | 50 (64) | 0.1 |

| ADL (IQR) | 4.5 (4-5) | 5 (4-6) | 0.2 |

| Decreased ADL (< 6) | 18 (82) | 49 (63) | 0.09 |

| IADL (IQR) | 6 (3-7) | 6 (4-8) | 0.3 |

| Decreased IADL (< 6) | 10 (45) | 27 (35) | 0.4 |

| Clock-Drawing test (IQR) | 5 (3-6) | 6 (5-7) | 0.06 |

| Cognitive Impairment (Mini Mental score < 24 or Mini-Cog < 3) | 6 (27) | 27 (35) | 0.5 |

| Impaired gait speed test (more than 7 seconds per 4.5 meters) | 15 (71) | 47 (62) | 0.5 |

| Impaired chair stand test (greater than 15 seconds) | 18 (95) | 53 (79) | 0.2 |

| Risk factors for Confusional Syndrome | 8 ± 2 | 6.5 ± 2.2 | 0.006 |

| Edmonton Frail Scale | 8 ± 2.5 | 5.8 ± 2.6 | 0.0006 |

| Frailty according to Edmonton (≥ 7) | 15 (68) | 33 (42) | 0.05 |

| Fried Frailty Index | 3.3 ± 1.2 | 2.5 ± 1.3 | 0.01 |

| Frailty according to Fried (≥ 3) | 17 (77) | 42 (54) | 0.05 |

| Number of falls in the past year | 12 (55) | 28 (36) | 0.1 |

| Hand Grip (kg) (IQR) | 18.5 (12-27) | 19 (14-28) | 0.5 |

| Preoperative Knee KSS | 27.4 ± 20.7 | 33.6 ± 16.5 | 0.2 |

| Preoperative Functional KSS | 31.8 ± 19.6 | 33.2 ± 21.2 | 0.8 |

For the descriptive analysis, continuous variables were expressed in means with the corresponding SD, or as medians and interquartile range, according to distribution. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages in absolute numbers.

The study population was divided into two groups according to whether they screened positive for depression. For categorical variables, χ² or Fisher were applied as needed, and for continuous variables, t test or Mann Whitney were used according to normal distribution. For our secondary endpoint analysis, association with age was estimated as a continuous variable through logistic regression. For our main hypothesis of studying the impact of depression on the variation in postoperative functional status, multivariate linear regression analysis was performed, with adjustment for potential confounders. These were selected based on variables that resulted statistically significant on bivariate analysis or that were considered clinically relevant by the investigators. Significance was defined with a P value less than 0.05. Estimations were reported along with the corresponding 95%CI. Data was processed and statistical measures were performed with STATA v14 software (StataCorp, TX, United States).

This study was conducted respecting considerations related to the care of participants in clinical research, according to national and international guidelines, including those established in the Declaration of Helsinki.

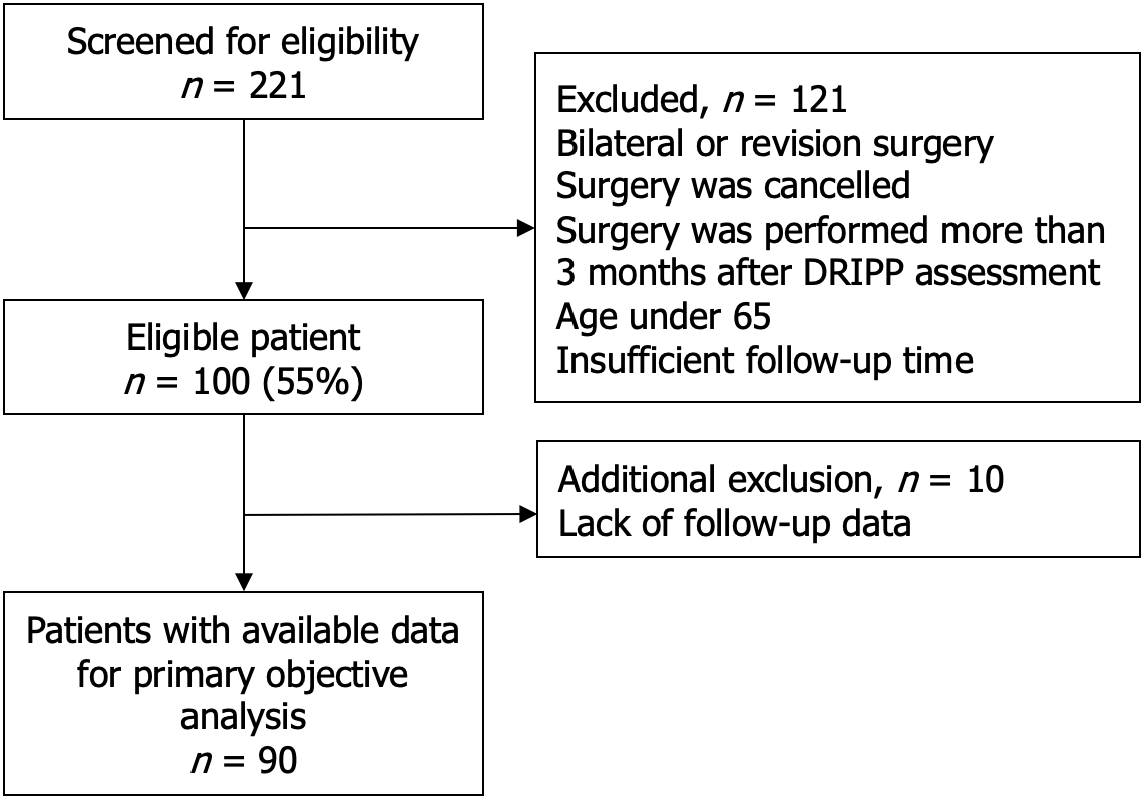

From a total of 221 patients that were screened for eligibility, 90 patients were included for final analysis (Figure 1). The small loss in follow-up in this study involving elderly patients was justified by the inherent challenges of this population, such as mobility issues, health complications, and varying levels of engagement, which affected their ability to participate consistently. Out of 100 patients that were included in the general analysis, 22 (22%) screened positive for depression. Overall, mean patient age was 80 years ± 6.3 years, with an average of 77.6 years ± 6 years in the subgroup with depression and 80.6 years ± 6.3 years in the non-depressed group (P = 0.05). Other statistically significant differences found between both groups at baseline was that 16 (73%) patients in the depressed population had hypertension vs 70

Patients with depression had significantly greater cognitive impairment as assessed by the clock-face drawing test with respective medians of 5 (3-6) vs 6 (5-7), (P = 0.06), as well as more risk factors for confusional syndrome: Mean 8 ± 2 vs 6.5 ± 2.2, (P = 0.006). Depressed patients were found to be significantly more frail when assessed through both Edmonton: 15 (68%) vs 33 (42%), (P = 0.05), and Fried: 17 (77%) vs 42 (54%), (P = 0.05). Only 7 patients with depression (32%) were currently receiving antidepressant treatment. No statistically significant differences were found between the remaining baseline characteristics, including KSS preoperative scores, between both study groups. The results are shown in Table 1.

The mean postoperative Functional KSS in patients with depression was 65 ± 22.1 vs 66.3 ± 20.3 in the non-depressed population (P = 0.8). The mean KSS was 78.9 ± 10.4 and 78.4 ± 13.7, (P = 0,9), in patients with and without depression respectively. Mean variation between pre and postoperative Functional KSS was 33.8 (27.2) and 34.5 (22.7), (P = 0,9); and variation in KSS was 50.2 (19.5) and 44.9 (19.5), (P = 0.28), in depressed vs non-depressed patients. None of these differences showed statistical significance upon analysis (Table 2). No association was found between depression and variation in KSS after performing linear regression analysis. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient resulted in -0.0304 (P = 0.8) for Functional KSS variation and -0.1 (P = 0.3) for KSS variation.

| Variable | Total (n = 90) | With depression (n = 21) | Without depression (n = 69) | P value |

| Postoperative Functional KSS | 66 ± 20.6 | 65 ± 22.1 | 66.3 ± 20.3 | 0.8 |

| Postoperative Knee KSS | 78 ± 13 | 78.9 ± 10.4 | 78.4 ± 13.7 | 0.9 |

| Delta Functional KSS | 34.4 ± 23.7 | 33.8 ± 27.2 | 34.5 ± 22.7 | 0.9 |

| Delta Knee KSS | 46.1 ± 19.6 | 50.2 ± 19.5 | 44.9 ± 19.5 | 0.3 |

Four patients (19%) presented major complications in the depressed group vs 16 (21%) among the non-depressed (P = 0.82). No significant differences were found upon individual analysis of each major complication (Table 3).

| Characteristic | With depression (n = 21) | Without depression (n = 75) | P value |

| Combined final event: Major complication or death. | 4 (19) | 16 (21.3) | 1 |

| Cerebrovascular accident (stroke) | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0) | N/A |

| Arrhythmia | 0 (0) | 1 (1.3) | N/A |

| Acute coronary event | 0 (0) | 1 (1.3) | N/A |

| Heart failure | 0 (0) | 5 (6.7) | N/A |

| Non-prosthetic infection | 1 (4.8) | 2 (2.7) | 0.5 |

| Periprosthetic infection | 0 (0) | 1 (1.3) | N/A |

| Acute renal failure | 1 (4.8) | 4 (5.3) | 1 |

| Major bleeding | 0 (0) | 2 (2.7) | N/A |

| Deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism | 1 (4.8) | 5 (6.7) | 1 |

| Death | 0 (0) | 1 (1.3) | N/A |

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to determine association between the independent variables (age, depression, frailty and high disease burden) and the combined event (death or major complication) at three months post surgery. Although none of these proved to be statistically significant, a statistical trend was described in association with age (Table 4). Finally, no statistically significant association was found between depression and length of hospital stay, readmission, number of physical therapy sessions or postoperative visits to the surgical team (Table 5).

| Independent variable | Odd ratio (95%CI) | P value |

| Depression | 1.2 (0.3–4.8) | 0.8 |

| Age | 1.1 (1–1.2) | 0.06 |

| Frailty (Fried Score ≥ 3) | 1.7 (0.5-6) | 0.4 |

| High Disease Burden (Charlson ≥ 2) | 1.3 (0.4–4.4) | 0.7 |

| Variable | With depression (n = 22) | Without depression (n = 78) | P value |

| Length of hospital stay | 4.5 ± 1.9 | 4.6 ± 2.9 | 0.8 |

| Readmission | 2 (9) | 8 (10) | 1 |

| Number of required sessions of physical therapy (IQR) | 10 (10–10) | 10 (10–10) | 0.8 |

| Number of consultations to the surgical team (IQR) | 4 (3–4) | 4 (3–4) | 0.3 |

The main finding of our study is that the presence of depression in elderly patients undergoing TKR does not seem to harm the postoperative functional status attained one year after surgery. This study allowed us to analyze our series of patients over 80 years old who suffer from depression and were treated with knee arthroplasty. It is the first registry to examine this phenomenon in the Latin American population. In addition to contributing to the understanding of our population, this work provides us with the opportunity to face new challenges in the treatment of these patients, enabling us to design intervention programs to address their depression from a multidisciplinary perspective. This is essential for improving their quality of life and facilitating their functional recovery. We acknowledge as a limitation of our work that the sample size could influence the validity of the findings and the implications this has for the applicability of the results to other populations. In the future, it will be necessary to conduct additional studies with larger and more diverse samples to validate the results and improve the generalizability of the study.

There is significant controversy in the published literature regarding the influence of depression on outcomes after TKA. The reasons for these contradictory findings are unclear. They could be related to methodological issues of the varied study protocols such as the timing and type of test used to screen for depression, the instrument used to evaluate functional status during follow-up, or variations in sample size and baseline patient demographics. These controversies may be represented in the analysis of two articles that evaluated the influence of depression and other factors on postoperative outcomes of TKA. While Lee et al[19] conclude that the presence of night pain, neuropathic pain, or depressive disorders does not adversely affect outcomes after surgery, Vajapey et al[20] suggest that depression may have an adverse impact on joint arthroplasty outcomes.

Findings similar to ours have been published in previous studies. In 2013, Pérez-Prieto et al[21] described that patients with depression experienced significant improvement 12 months after surgery, and that this recovery was greater than that of non-depressed patients in several domains. They also reported that 86.8% of patients were no longer depressed one year after surgery[21]. Lingard and Riddle[22], did not specifically address depression in their study population, but assessed the impact of psychological distress, as measured by the Short Form 36 Health Survey mental health questionnaire, on postoperative outcomes. They found that the changes in the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) pain and function scores for psychologically distressed patients were not significantly different from those for non-distressed patients. Nonetheless, a study published in 2007 that included 83 patients with a mean age of 66 years found that preoperative pain and depression were predictive of lower Functional KSS up to five years after surgery[23].

Cooper et al[4] screened patients for depressive disorder at baseline and a year after TKA and divided them into four groups: (1) Those who had no depressive disorder; (2) Those who had gained depression; (3) Those who had lost or resolved depression; and (4) Those who continued to maintain a depressive state. Depressed patients showed impaired recovery when measured by KSS and WOMAC scores.

The study highlights a concerning disconnect between the prevalence of cognitive impairment in depressed patients and the low treatment rates, suggesting a need for increased awareness and intervention strategies to address both mental health and cognitive functioning.

Other important aspects to take into consideration are the health costs and financial burden derived from associated comorbidities in patients undergoing TKA. Pugely et al[24] described the following factors that contribute to increased hospital costs and length of stay: (1) Inpatient death; (2) Ethnic minorities; (3) Recent weight loss; (4) Pulmonary-circulatory disorders; and (5) Hydroelectrolytic disturbances. Our research has proved that depressed patients do not have significantly increased healthcare resource requirements. In comparison with the non-depressed population, depressed patients did not present prolonged hospital stays, nor a greater number of physical therapy sessions or postoperative visits with the surgical team. One of the study's limitations is the small sample size. This is due in part to the fact that we only included patients who underwent surgery at a single site with a specific team. The other contributing factor was loss during follow-up. Several patients did not comply with the number of prespecified control visits and were thus excluded from the analysis. Nonetheless, our institution receives patient referrals from the whole country, which allows for a balanced population sample from a sanitary, social, and economic standpoint.

The presence of depression in patients with osteoarthritis should not be a limiting factor for surgical planning. The identification and treatment of depression before surgery may be an important strategy for the improvement of symptoms such as pain, reduction of the risk for acute confusional syndrome, cognitive impairment and subsequent development of frailty.

Elderly patients tend to accumulate multiple comorbidities and geriatric syndromes, which underscores the importance of integrated preoperative geriatric assessment. We believe that interdisciplinary work between geriatric specialists and surgical teams is vital in improving patient outcomes.

| 1. | Ellis HB, Howard KJ, Khaleel MA, Bucholz R. Effect of psychopathology on patient-perceived outcomes of total knee arthroplasty within an indigent population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:e84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Visser MA, Howard KJ, Ellis HB. The Influence of Major Depressive Disorder at Both the Preoperative and Postoperative Evaluations for Total Knee Arthroplasty Outcomes. Pain Med. 2019;20:826-833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gebauer SC, Salas J, Tucker JL, Callahan LF, Scherrer JF. Depression and Time to Knee Arthroplasty Among Adults Who Have Knee Osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty. 2024;39:2452-2457.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Heijbel S, W-Dahl A, E-Naili J, Hedström M. Patient-Reported Anxiety or Depression Increased the Risk of Dissatisfaction Despite Improvement in Pain or Function Following Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Swedish Register-Based Observational Study of 8,745 Patients. J Arthroplasty. 2024;39:2708-2713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Jones AR, Al-Naseer S, Bodger O, James ETR, Davies AP. Does pre-operative anxiety and/or depression affect patient outcome after primary knee replacement arthroplasty? Knee. 2018;25:1238-1246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | By the 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria® for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:674-694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1181] [Cited by in RCA: 1979] [Article Influence: 282.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Katz S, Akpom CA. 12. Index of ADL. Med Care. 1976;14:116-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 248] [Cited by in RCA: 266] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Guigoz Y, Vellas B, Garry PJ. Assessing the nutritional status of the elderly: The Mini Nutritional Assessment as part of the geriatric evaluation. Nutr Rev. 1996;54:S59-S65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 744] [Cited by in RCA: 864] [Article Influence: 28.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Rolfson DB, Majumdar SR, Tsuyuki RT, Tahir A, Rockwood K. Validity and reliability of the Edmonton Frail Scale. Age Ageing. 2006;35:526-529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 758] [Cited by in RCA: 1101] [Article Influence: 55.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T, Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, McBurnie MA; Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M146-M156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13384] [Cited by in RCA: 16974] [Article Influence: 679.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 11. | Seitz DP, Chan CC, Newton HT, Gill SS, Herrmann N, Smailagic N, Nikolaou V, Fage BA. Mini-Cog for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease dementia and other dementias within a primary care setting. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;2:CD011415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bernabeu-Wittel M, Ollero-Baturone M, Moreno-Gaviño L, Barón-Franco B, Fuertes A, Murcia-Zaragoza J, Ramos-Cantos C, Alemán A, Fernández-Moyano A. Development of a new predictive model for polypathological patients. The PROFUND index. Eur J Intern Med. 2011;22:311-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lee SJ, Lindquist K, Segal MR, Covinsky KE. Development and validation of a prognostic index for 4-year mortality in older adults. JAMA. 2006;295:801-808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 538] [Cited by in RCA: 572] [Article Influence: 28.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Schonberg MA, Davis RB, McCarthy EP, Marcantonio ER. External validation of an index to predict up to 9-year mortality of community-dwelling adults aged 65 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1444-1451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Whooley MA, Avins AL, Miranda J, Browner WS. Case-finding instruments for depression. Two questions are as good as many. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:439-445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1226] [Cited by in RCA: 1180] [Article Influence: 40.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, Leirer VO. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 17:37-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8972] [Cited by in RCA: 9572] [Article Influence: 217.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yesavage JA, Sheikh JI. 9/Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS). Clin Gerontologist. 1986;5:165-173. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3109] [Cited by in RCA: 3176] [Article Influence: 176.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Insall JN, Dorr LD, Scott RD, Scott WN. Rationale of the Knee Society clinical rating system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;13-14. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Lee NK, Won SJ, Lee JY, Kang SB, Yoo SY, Chang CB. Presence of Night Pain, Neuropathic Pain, or Depressive Disorder Does Not Adversely Affect Outcomes After Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Prospective Cohort Study. J Korean Med Sci. 2022;37:e309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Vajapey SP, McKeon JF, Krueger CA, Spitzer AI. Outcomes of total joint arthroplasty in patients with depression: A systematic review. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2021;18:187-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Pérez-Prieto D, Gil-González S, Pelfort X, Leal-Blanquet J, Puig-Verdié L, Hinarejos P. Influence of depression on total knee arthroplasty outcomes. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29:44-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lingard EA, Riddle DL. Impact of psychological distress on pain and function following knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:1161-1169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Brander V, Gondek S, Martin E, Stulberg SD. Pain and depression influence outcome 5 years after knee replacement surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;464:21-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 255] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Pugely AJ, Martin CT, Gao Y, Belatti DA, Callaghan JJ. Comorbidities in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty: do they influence hospital costs and length of stay? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:3943-3950. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/