Published online Dec 25, 2025. doi: 10.5527/wjn.v14.i4.111613

Revised: August 3, 2025

Accepted: November 7, 2025

Published online: December 25, 2025

Processing time: 172 Days and 13.1 Hours

Diabetic patients with atypical presentation are often challenging in terms of diagnosis and management. Kidney biopsy is not routinely done in diabetics, and clinicians are always in a dilemma in such a scenario to decide whether to do a biopsy or not. Since non-diabetic kidney diseases (NDKD) are common, and some patients may have NDKD superimposed on diabetic kidney diseases (DKD), therefore, kidney biopsy may be warranted to rule out NDKD.

To determine the prevalence of NDKD, DKD, or mixed lesions, identify predictors of NDKD, and investigate renal and patient survival, as well as factors associated with these outcomes.

This retrospective observational study was conducted on patients with biopsy-proven NDKD, DKD, and mixed lesions (having both NDKD and DKD). Binary logistic regression models were constructed to identify predictors of NDKD. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was performed to compare time to kidney failure and patient survival across the three histological groups. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression was used to identify clinical and pathological factors associated with kidney failure and all-cause mortality.

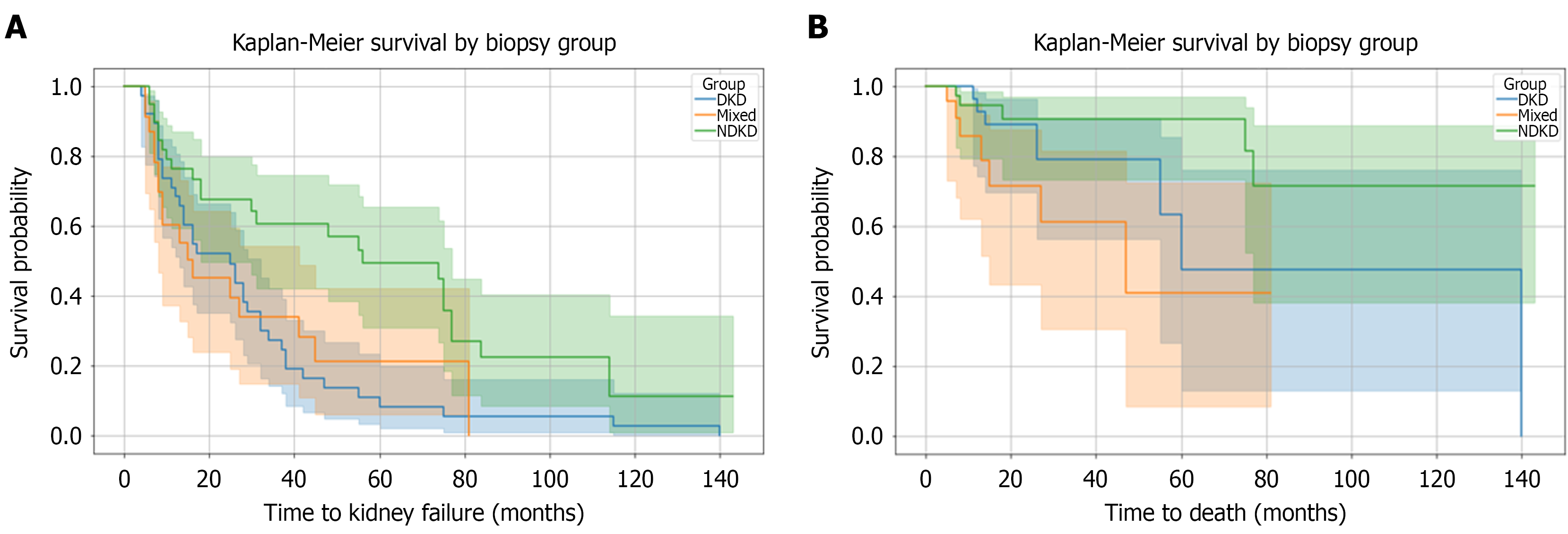

A total of 103 biopsies were analyzed. Sixty-four (62.1%) had NDKD alone or mixed lesions. The most common NDKD pathologies were interstitial nephritis in 12 (29.2%), focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in 10 (24.4%), and immune complex–mediated glomerulonephritis in five (12.2%) patients. Compared to DKD, NDKD was associated with significantly lower odds of proteinuria > 3.5 g/day [odds ratio (OR), 0.02; P = 0.0015], retinopathy (OR = 0.04; P = 0.0067), and diabetes duration ≥ 10 years (OR = 0.01; P = 0.0002). However, NDKD had higher odds of anemia (Hemoglobin < 12 g/dL; OR = 9.56; P = 0.0107) and creatinine levels > 180 μmol/L (OR = 18.68; P = 0.0063). Kaplan-Meier analysis showed significant differences in renal survival (log-rank P = 0.0033). Patients with NDKD have the best outcomes, while those with DKD have the worst. In a multivariable Cox regression analysis, increasing age, creatinine, arteriosclerosis, and severe interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy were independently associated with kidney failure. At the same time, the use of renin angiotensin system blockers was protective (hazard ratio = 0.43, P = 0.02). Kaplan-Meier curves for patient survival also differed significantly (log-rank P = 0.018); patients in the mixed group showed the highest mortality, while those with NDKD showed the lowest. Mortality was independently associated with older age, hypoalbuminemia, diabetic retinopathy, arteriosclerosis, and higher creatinine.

NDKD and mixed lesions are frequent in diabetic patients. These histological lesions carry distinct prognostic implications. Clinical features such as a shorter diabetes duration, absence of retinopathy, anemia, and elevated creatinine levels suggest NDKD and warrant biopsy. NDKD had better renal and patient survival rates, while mixed lesions had the worst outcomes. Older age, hypoalbuminemia, retinopathy, arteriosclerosis, and elevated creatinine were key predictors of mortality.

Core Tip: Diabetic patients have non-diabetic kidney diseases (NDKD) alone or with diabetic kidney diseases (DKD) in 62.1%. Compared to DKD, NDKD was associated with significantly lower odds of heavy proteinuria, retinopathy, and long-standing diabetes. However, NDKD had higher odds of anemia. NDKD patients experienced better renal and patient survival outcomes. Increasing age, creatinine, arteriosclerosis, interstitial fibrosis, and tubular atrophy were independently associated with kidney failure. Renin angiotensin system blockers were found to be protective in preventing kidney failure. Mortality was independently associated with older age, hypoalbuminemia, diabetic retinopathy, arteriosclerosis, and higher creatinine.

- Citation: Al-Qurashi SH, Khalil MAM, Mahmood HHK, A Al-Ghamdi R, Alsharif MM, Said Ahmed MA, Alghamdi RMH, Sadagah NM. Predictors of non-diabetic kidney disease in diabetics: A Saudi Arabian perspective. World J Nephrol 2025; 14(4): 111613

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-6124/full/v14/i4/111613.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5527/wjn.v14.i4.111613

Diabetes mellitus is a global health challenge across the world. It is estimated that the number of adults with diabetes will increase from 630 million in 1990 to 828 million in 2028. This represents a rise in prevalence from 7% to 14% between 1990 and 2022[1]. Around 40% of type 2 diabetes mellitus patients will develop chronic kidney disease (CKD)[2]. The prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus is alarmingly high in Saudi Arabia, rising from 8.5% in 1992 to 39.5% in 2022[3], and it’s the leading cause of CKD in Saudi Arabia[4]. Given this growing burden of diabetes and its renal complications, an important question arises about how best to evaluate kidney dysfunction in these patients. The decision to do a kidney biopsy in patients with diabetes is often tricky. Generally, nephrologists may be inclined to attribute kidney dysfunction to diabetic kidney disease without doing a biopsy. However, it is essential to mention that having non-diabetic kidney disease (NDKD) is not uncommon in diabetics[5,6]. Clinicians may opt for a kidney biopsy in diabetic patients without retinopathy, a rapid decline in kidney function, a rapid increase in proteinuria, the sudden appearance of nephrotic syndrome, active sediment, or the emergence of signs and symptoms of systemic diseases[7]. Considering the dilemma between diabetic and NDKD, obtaining a histological diagnosis is crucial. A kidney biopsy can accurately identify a variety of lesions, ranging from classic diabetic nephropathy to mixed lesions and entirely NDKD. Our study aimed to explore the histological spectrum in diabetic patients undergoing biopsy and to determine predictors of NDKD. We also investigated renal and patient survival, as well as factors associated with these outcomes.

This retrospective study was conducted at the Center of Renal Diseases and Transplantation at King Fahad Armed Forces Hospital, Jeddah. Following approval by the ethics review committee, data were collected between 2000 and 2024 for all diabetic patients who underwent a kidney biopsy. The study included patients with both type 1 diabetes mellitus and type 2 diabetes mellitus who were 14 years of age or older and underwent a native kidney biopsy at our center between 2000 and 2024.

The prevalence of NDKD, mixed lesions, and isolated diabetic kidney diseases (DKD) was calculated using the total number of diabetic patients who underwent native kidney biopsy at our center between 2000 and 2024 (n = 103) as the population at risk. In addition, we also evaluated long-term outcomes, including kidney failure and all-cause mortality. We also studied the predictors of kidney failure and all-cause mortality using survival analysis. The predictors of kidney failure studied included clinical factors such as proteinuria > 3.5 g/day, hemoglobin < 12 g/dL, presence of retinopathy, duration of diabetes ≥ 10 years, age, and serum creatinine > 180 μmol/L, as well as histopathological features such as moderate to severe interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy (IFTA), global glomerulosclerosis ratio, and podocyte effacement. A multivariate Cox proportional hazards model was used to identify independent predictors of all-cause mortality, including age, serum creatinine, hemoglobin < 12 g/dL, serum albumin < 30 g/L, retinopathy, and arteriosclerosis.

Kidney failure was defined as a composite endpoint comprising an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of < 20 mL/minute/1.73 m2, initiation of dialysis, or kidney transplantation. The eGFR threshold of < 20 mL/minute/1.73 m2 was chosen due to its clinical relevance, as this is the level at which, under current practice guidelines and recommendations, patients are typically referred for preemptive kidney transplant evaluation and vascular access planning[8].

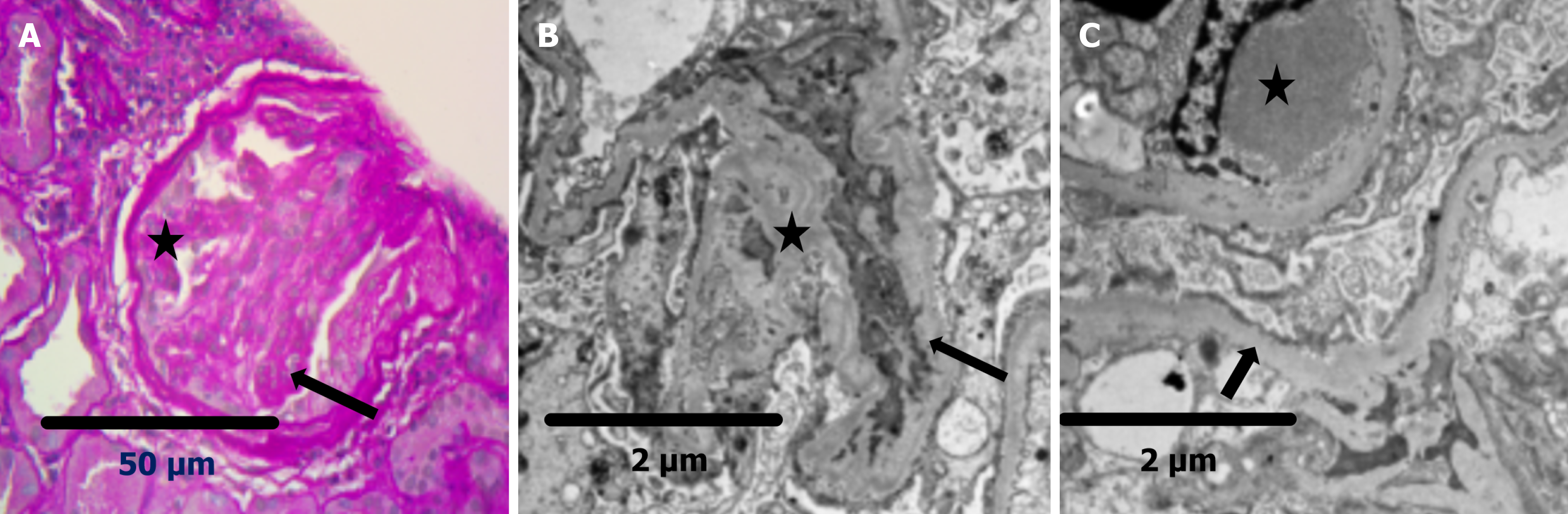

Biopsy was performed in patients with atypical presentation, such as unexplained kidney dysfunction, sudden onset of proteinuria, hematuria, rapidly declining renal function, shorter duration of diabetes, or absence of diabetic retinopathy. Patients with adequate biopsy tissue were included in the analysis. We excluded patients with previously known NDKD before the diagnosis of diabetes. Patients with a kidney transplant, or biopsy done for mass lesions, or those under 14 years of age were also excluded. One core each for light microscopy and immunofluorescence studies was analyzed. The biopsy tissues were examined under light microscopy using hematoxylin and eosin, Masson’s trichrome, and periodic acid methenamine silver stains to assess glomerular, tubular, interstitial, and vascular pathological changes. Immunofluorescence studies were performed using antisera against human immunoglobulin G, immunoglobulin A (IgA), immunoglobulin M, C3, C1q, kappa, and lambda light chains, as well as fibrinogen, to assess immune complex deposition. Electron microscopy was performed in selected cases to analyze details of basement membrane changes and other ultrastructural alterations. Two experienced renal pathologists interpreted all findings. The presence of nodular or diffuse mesangial expansion, hyalinosis of afferent and efferent arterioles, thickening of the glomerular basement membrane, and the presence of exudative lesions such as fibrin cap and capsular drop were labeled as diabetic nephropathy[7].

The pathological diagnosis and classification of DKD were based on the 2010 classifications of the Renal Pathology Society, which included four groups[9]. Class I included glomeruli that appeared normal on light microscopy but exhibited thickening of the glomerular basement membrane. Class II was defined by mesangial expansion without nodular sclerosis. Class III was characterized by the presence of at least one Kimmelstiel-Wilson nodular lesion, with less than 50% of glomeruli showing global sclerosis. Class IV represented advanced diabetic glomerulosclerosis, with more than 50% of glomeruli globally sclerosed. IFTA was classified as absent (< 10%), mild (10%-24%), moderate (25%-50%), and severe (> 50%) of the tissues[10]. Arteriosclerosis was reported as none (0% luminal narrowing), mild (≤ 25% luminal narrowing), moderate (26%-50% luminal narrowing), and severe (> 50% luminal narrowing or reported as severe)[11].

The following clinical and laboratory parameters were collected at the time of kidney biopsy, where available: Age, gender, type and duration of diabetes, history of hypertension, smoking, dyslipidemia, diabetic retinopathy, neuropathy, and family history of diabetes or CKD. Cardiovascular comorbidities such as coronary artery disease, peripheral arterial disease, and stroke were noted. Past history and duration of proteinuria, as well as deranged renal function, were also reported. The presence of hematuria and proteinuria was also noted. Laboratory investigations, including serum albumin, total protein, serum creatinine, eGFR, hemoglobin, calcium, phosphate, intact parathyroid hormone (PTH), and glycated hemoglobin, were also collected. Data for medications such as insulin, oral hypoglycemic agents, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (empagliflozin or dapagliflozin), antihypertensive therapy, use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and statins were also collected. Immunological investigations, including complement levels (C3, C4), antinuclear antibody, anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA), C-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), and P-ANCA, as well as serology for hepatitis B surface antigen, anti-hepatitis C antibodies, and human immunodeficiency virus, were also recorded. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, some data were not available for all patients. Therefore, only the available information was analyzed for each variable using a complete-case approach. To minimize bias, we ensured careful selection of variables with sufficient data and conducted sensitivity analyses where possible to assess the robustness of our findings. As a result, the reduced sample size for some analyses related to NDKD or DKD may have limited the statistical power and generalizability of these results. This has been recognized as a limitation of the study.

Based on kidney biopsy findings, lesions were classified as pure DKD, NDKD, and mixed lesions (NDKD + DKD). For analysis to identify predictors of NDKD, patients were grouped into two groups. Group I included those with pure DKD, while Group II included those with NDKD. This grouping was used to compare clinical and laboratory features between patients with isolated diabetic nephropathy and those with additional or alternative renal pathologies. Kaplan-Meier curves for DKD, mixed lesions, and NDKD were used to assess time to kidney failure using eGFR at the time of biopsy as the starting point and kidney failure as the endpoint. The Kaplan-Meier survival plot was also used to compare time to death among three histologically defined groups: DKD, mixed, and NDKD, using eGFR at the time of biopsy, the time-to-event variable, and mortality as the event. Risk factors for kidney failure and mortality for the whole cohort using Cox regression analysis.

Continuous variables were summarized using median and interquartile range. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables included age, duration of diabetes, hemoglobin A1c, creatinine levels (at biopsy, 1 year, and 2 years), eGFR (at 1 and 2 years), hemoglobin, PTH, calcium, phosphate, total protein, albumin, proteinuria (g/day), total glomeruli count, global and segmental sclerosis counts and ratios, IFTA severity, arteriosclerosis severity, and hyalinosis severity. Categorical variables included gender, diabetes type, presence of retinopathy, hypertension, dyslipidemia, neuropathy, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular comorbidities, medication use (including angiotensin enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, statins, insulin, oral hypoglycemics, and sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors, indication for biopsy, presence of hematuria, crescent formation, IFTA (≥ 25%), podocyte effacement, antinuclear antibody, anti-dsDNA, complement levels (C3, C4), ANCA (C-ANCA, P-ANCA), kidney failure, and mortality.

Group comparisons were made using Student’s t-test, Mann-Whitney U test, χ2, or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to identify independent predictors of DKD vs NDKD and mixed lesions. Survival analysis was carried out using Cox proportional hazards regression to identify predictors of kidney failure and all-cause mortality. Kaplan-Meier curves with log-rank tests were used to compare time to kidney failure and mortality across biopsy groups. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

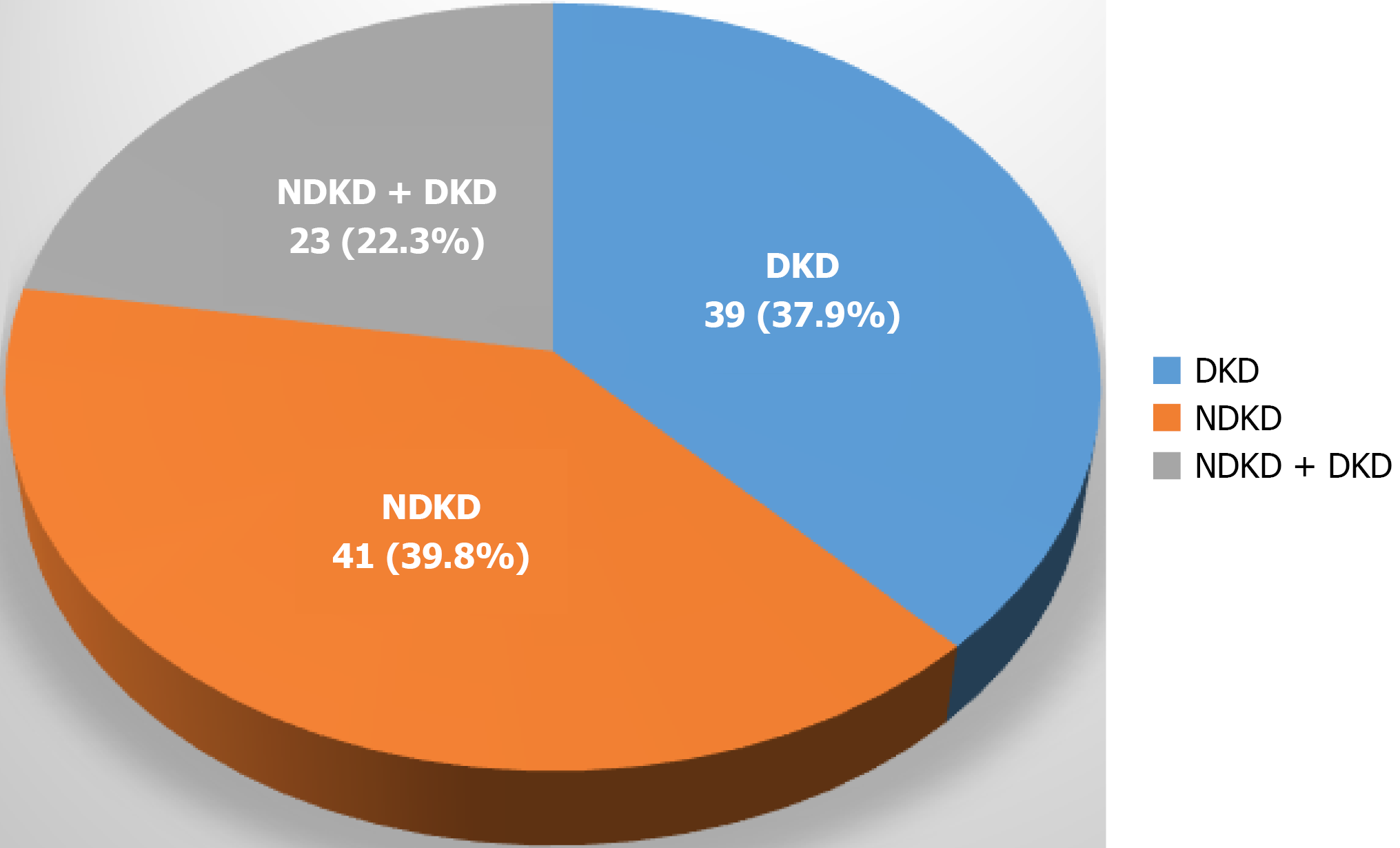

Three hundred and fifty-nine biopsies were performed in the study period. Out of 359 biopsies, 106 were performed on individuals with diabetes. After excluding three kidney biopsies for mass lesions, a total of 103 out of 359, representing 28.69% of the total, were analyzed. Sixty-four (62.1%) patients had NDKD alone or mixed lesions (NDKD with DKD). Of these, 41 (39.8%) were diagnosed with NDKD, 23 (22.3%) with mixed lesions, and 39 (39.8%) with pure DKD. The most frequent pathology in the NDKD group was interstitial nephritis in 12 (29.2%), followed by focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) in 10 (24.4%) and immune complex-mediated glomerulonephritis in five (12.2%) patients. Among mixed lesions, immune complex-mediated glomerulonephritis was present in six (26.1%) and IgA nephropathy in four (17.4%). Other less frequent findings included membranous nephropathy, lupus nephritis, chronic pyelonephritis, and rare entities such as C1q nephropathy, C3 glomerulopathy, fibrillary GN, and pauci-immune vasculitis. The detailed distribution of biopsy findings is presented in Table 1. Figure 1 shows the prevalence of NDKD, DKD, and mixed lesions. Figure 2 shows light microscopy and electron microscopy showing a mixed lesion of FSGS and diabetic nephropathy. Among patients with DKD, the most common histological classification was Class 4, seen in 16 patients (41.0%). This was followed by Class 3 in 15 patients (38.5%) and Class 2 in seven patients (17.9%). Only one patient (2.6%) had early-stage disease classified as Class 1. Overall, the majority of patients had moderate to advanced DKD lesions. Table 2 shows the stages of histologically proven DKD.

| Biopsy category | NDKD | NDKD + DKD | Total |

| Interstitial nephritis | 12 (29.2) | - | 12 (18.2) |

| FSGS | 10 (24.4) | 3 (13.0) | 13 (20.3) |

| Immune complex glomerulonephritis | 5 (12.2) | 6 (26.1) | 11 (17.2) |

| IgA | 2 (4.9) | 4 (17.4) | 6 (9.4) |

| Membranous | 4 (9.8) | 2 (8.7) | 6 (9.4) |

| Lupus nephritis | 4 (9.8) | - | 4 (6.2) |

| Chronic pyelonephritis | - | 2 (8.7) | 2 (3.1) |

| Minimal change disease | 3 (7.3) | - | 3 (4.7) |

| Multiple myeloma | 1 (2.4) | 1 (4.3) | 2 (3.1) |

| C1Q nephropathy | - | 1 (4.3) | 1 (1.6) |

| C3 glomerulopathy | - | 1 (4.3) | 1 (1.6) |

| Fibrillary glomerulonephritis | - | 1 (4.3) | 1 (1.6) |

| Pauci-immune vasculitis | - | 1 (4.3) | 1 (1.6) |

| Post-infectious glomerulonephritis | - | 1 (4.3) | 1 (1.6) |

| Total | 41 (100.0) | 23 (100.0) | 64 (100.0) |

| DKD classification | n (%) |

| Class 4 | 16 (41.0) |

| Class 3 | 15 (38.5) |

| Class 2 | 7 (17.9) |

| Class 1 | 1 (2.6) |

The median age in our cohort was significantly higher in the DKD + NDKD group (69.0 years) compared to the DKD (53.0 years) and NDKD (50.0 years) groups (P = 0.0003). There were no significant differences in gender distribution across groups (P = 0.3518). We observed that type 1 diabetes mellitus was more common in the DKD group, present in 10 patients (n = 10, 26.3%) as compared to DKD + NDKD (n = 1, 4.3%) and NDKD (n = 1, 2.4%) groups (P = 0.0020). The duration of diabetes varied significantly among the groups. We observed the longest duration in DKD (median 168 months), followed by DKD + NDKD (108 months), and the shortest in NDKD (60 months) (P < 0.0001). Hemoglobin A1c levels were similar between the groups (P = 0.2877). Diabetic retinopathy was significantly more common in the DKD group (n = 23, 59.0%) than in the DKD + NDKD (n = 9, 39.1%) and NDKD (n = 10, 24.4%%) groups (P = 0.0070).

While examining comorbidities, we found no significant differences in the prevalence of hypertension (P = 0.3005) or dyslipidemia (P = 0.9336) across all groups. However, we found that neuropathy was more frequent in the DKD group (n = 22, 61.1%) compared to the DKD + NDKD group (n = 11, 55%) and the NDKD group (n = 2, 9.1%) (P = 0.0003). Coronary artery disease was more common in the DKD group (n = 23, 65.7%) than in DKD + NDKD (n = 8, 42.1%) and NDKD (n = 1, 14.2%) (P = 0.0000). Similarly, peripheral artery disease and stroke were more prevalent in DKD patients (n = 30, 85.7% and n = 28, 77.8% respectively) and were less frequent in the other two groups (both P < 0.0001).

We analyzed the indication for the biopsy. We found that sudden renal function decline was the most common indication in the NDKD group (58.5%) and DKD + NDKD group (52.2%). However, it was a less common indication in DKD (30.8%). Conversely, a rise in proteinuria was the predominant indication for biopsy in DKD patients (51.3%) but was less common in DKD + NDKD (30.4%) and rare in NDKD (17.1%). Hematuria as an indication for biopsy was not significantly different across all groups (P = 0.2809). Analysis of glomerular sclerosis revealed important features in our study. We found the lowest total glomeruli count in the NDKD group (median 10.0, interquartile range 8.0-17.0) compared to the DKD and mixed groups (P = 0.0154). Global glomerulosclerosis was significantly more common in the DKD group, with a median of 5.0 globally sclerosed glomeruli. This was in contrast to 4.0 in the mixed group and 2.0 in the NDKD group (P = 0.0007). Similarly, the global sclerosis ratio was highest in the DKD group (median 0.3). From this, we can infer that nearly one-third of the glomeruli were globally sclerosed. This was higher when compared to 0.2 in the mixed group and 0.1 in the NDKD group (P = 0.0212). We also found higher segmental sclerosis count and ratio in DKD. However, this achieved statistical significance only for the count (P = 0.0399), and not for the ratio (P = 0.6571). From these findings, we can deduce that DKD is associated with more extensive chronic glomerular damage. On the other side, NDKD may present with relatively preserved glomerular architecture.

We observed more crescents in DKD + NDKD (21.7%) and NDKD (12.2%) compared to DKD (0.0%) (P = 0.0567). This indicates more active inflammatory injury in non-diabetic or mixed lesions. IFTA ≥ 25% were most prevalent in the DKD + NDKD group (77.3%), followed by NDKD (69,7%) and DKD (41.0%) (P = 0.0073). The severity of IFTA differed significantly across the three biopsy-based groups (P = 0.0019). It was interesting to note that severe IFTA (> 50%) was observed exclusively in the DKD group (Group I), affecting 25.6% of patients. At the same time, it was absent in both the mixed (DKD + NDKD) and NDKD groups. Moderate IFTA (25%-50%) was also more common in the DKD group (33.3%), compared to 22.7% in the mixed group and 30.3% in the NDKD group. The absence of IFTA (< 10%) was infrequent across all groups. We observed no significant differences in the presence or severity of arteriosclerosis, nor hyalinosis scores, across the groups. The severity of podocyte effacement, as assessed by electron microscopy, differed significantly among the three groups (P = 0.0042) on univariate analysis. Diffuse effacement (> 50%) was most frequent in the NDKD group (52.0%), compared to 30.0% in the mixed group and 26.3% in the DKD group. Focal effacement (≤ 50%) was also more commonly reported in the NDKD and mixed groups (36.0% and 20.0%, respectively) than in the DKD group (7.9%). We also looked into renal and patient outcomes. Kidney failure, defined as a composite of sustained eGFR < 20 mL/minute/1.73 m2, initiation of dialysis, or kidney transplantation, was significantly more common in the DKD group (97.4%) compared to the DKD + NDKD (65.2%) and NDKD (61.0%) groups (P = 0.0002). This reflects poorer renal survival in patients with pure diabetic nephropathy.

We found comparable creatinine levels at the time of the biopsy; however, we observed significant divergence at 1 year, where the median creatinine was highest in the DKD group (483.5 μmol/L), compared to the DKD + NDKD group (352.0 μmol/L) and the NDKD group (124.0 μmol/L) (P = 0.0000). A similar trend was observed at 2 years (P = 0.0002). We found significantly lower eGFR at 1 year (P = 0.056) and 2 years (P = 0.0372). This indicates a more rapid decline in kidney function in patients with DKD. It was interesting to note that anemia was also more prevalent in DKD patients. DKD patients had the lowest median hemoglobin levels (10.0 g/dL), followed by DKD + NDKD (11.1 g/dL) and NDKD (12.1 g/dL) (P = 0.0013). We observed significantly higher protein-to-creatinine ratios in the DKD group. The DKD group had a protein-to-creatinine ratio (7.04 g/mmol) compared to the DKD + NDKD (1.80) and NDKD (2.90) groups (P = 0.0187). We found no significant differences in albumin, calcium, phosphate, and PTH levels.

Kidney failure (defined as a composite of sustained eGFR < 20 mL/minute/1.73 m2, dialysis initiation, or kidney transplantation) was noted most frequently in the DKD group (97.4%), followed by the mixed group (65.2%) and NDKD group (61.0%). The difference across groups was statistically significant (P = 0.0002). This suggests a markedly higher risk of progression to kidney failure among patients with pure diabetic kidney disease. We observed the highest mortality in the mixed group (30.4%), followed by the DKD group (20.5%) and the NDKD group (12.2%). However, these differences between the three groups were not statistically significant (P = 0.2038). Cardiac causes and malignancy were less common. Table 3 describes baseline demographic and clinical characteristics.

| Variable | DKD (n = 39) | DKD + NDKD (n = 23) | NDKD (n = 41) | P value |

| Gender | 0.3518 | |||

| Male | 20 (51.3) | 16 (69.6) | 25 (61.0) | |

| Female | 19 (48.7) | 7 (30.4) | 16 (39.0) | |

| Age, median (IQR) | 53.0 (42.0-66.0) | 69.0 (61.5-74.0) | 50.0 (46.0-61.0) | 0.0003 |

| Diabetes diagnosis | 1.0000 | |||

| Yes | 39 (100.0) | 23 (100.0) | 41 (100.0) | |

| Diabetes type | 0.0020 | |||

| Type 1 | 10 (26.3) | 1 (4.3) | 1 (2.4) | |

| Type 2 | 28 (73.7) | 22 (95.7) | 40 (97.6) | |

| Duration of diabetes (months) | 168.0 (120.0-240.0) | 180.0 (36.0-216.0) | 60.0 (12.0-108.0) | < 0.0001 |

| Haemoglobin A1c level | 7.1 (5.9-8.3) | 7.2 (6.3-9.2) | 6.8 (6.3-9.2) | 0.5502 |

| Retinopathy | 0.0070 | |||

| Yes | 23 (59.0) | 9 (39.1) | 10 (24.4) | |

| No | 16 (41.0) | 14 (60.9) | 31 (75.6) | |

| Hypertension | 0.3005 | |||

| Yes | 34 (91.9) | 20 (100.0) | 35 (97.2) | |

| No | 3 (8.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.8) | |

| Dyslipidaemia | 0.9336 | |||

| Yes | 23 (60.5) | 13 (59.1) | 22 (56.4) | |

| No | 15 (39.5) | 9 (40.9) | 17 (43.6) | |

| Neuropathy | 0.0003 | |||

| Yes | 22 (61.1) | 11 (55.0) | 2 (9.1) | |

| No | 14 (38.9) | 9 (45.0) | 20 (90.9) | |

| Coronary artery disease | 0.0000 | |||

| Yes | 23 (65.7) | 8 (42.1) | 1 (4.2) | |

| No | 12 (34.3) | 11 (57.9) | 23 (95.8) | |

| Peripheral artery disease | < 0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 30 (85.7) | 12 (63.2) | 1 (4.0) | |

| No | 5 (14.3) | 7 (36.8) | 24 (96.0) | |

| Stroke | 0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 28 (77.8) | 12 (63.2) | 5 (20.8) | |

| No | 8 (22.2) | 7 (36.8) | 19 (79.2) | |

| Blood pressure-lowering medications | 0.5112 | |||

| ≥ 1 medication | 36 (92.3) | 19 (82.6) | 36 (87.8) | |

| 0 medication | 3 (7.7) | 4 (17.4) | 5 (12.2) | |

| ACE inhibitor use | 0.1394 | |||

| Yes | 11 (30.6) | 3 (13.0) | 6 (14.6) | |

| No | 25 (69.4) | 20 (87.0) | 35 (85.4) | |

| ARBs use | 0.6285 | |||

| Yes | 21 (56.8) | 11 (47.8) | 19 (46.3) | |

| No | 16 (43.2) | 12 (52.2) | 22 (53.7) | |

| Statin use | 0.6736 | |||

| Yes | 29 (78.4) | 19 (82.6) | 30 (73.2) | |

| No | 8 (21.6) | 4 (17.4) | 11 (26.8) | |

| Insulin use | 0.000 | |||

| Yes | 29 (76.3) | 15 (65.2) | 11 (26.8) | |

| No | 9 (23.7) | 8 (34.8) | 30 (73.2) | |

| Oral hypoglycemics | 0.2538 | |||

| Yes | 17 (45.9) | 8 (34.8) | 23 (56.1) | |

| No | 20 (54.1) | 15 (65.2) | 18 (43.9) | |

| SGLT2 inhibitor use | 0.8871 | |||

| Yes | 2 (5.7) | 1 (4.3) | 3 (7.3) | |

| No | 33 (94.3) | 22 (95.7) | 38 (92.7) | |

| Creatinine at biopsy (µmol/L) | 295.0 (166.0-596.5) | 323.0 (193.5-547.5) | 210.0 (105.0-580.0) | 0.3004 |

| Creatinine at 1 year | 483.5 (211.0-694.8) | 352.5 (157.0-551.2) | 124.0 (89.5-182.5) | 0.0000 |

| Creatinine at 2 years | 491.0 (243.0-891.0) | 302.0 (134.0-561.0) | 122.0 (92.0-169.0) | 0.0002 |

| eGFR at 1 year | 16.0 (11.0-25.5) | 34.0 (19.5-44.5) | 45.5 (22.8-77.2) | 0.0056 |

| eGFR at 2 years | 19.0 (15.0-22.0) | 30.5 (13.0-47.8) | 55.0 (32.0-77.0) | 0.0372 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.0 (9.1-11.1) | 11.1 (9.8-14.5) | 12.1 (10.4-78.3) | 0.0013 |

| Yes (Hb < 12) | 30 (76.9) | 14 (60.9) | 18 (43.9) | |

| No (Hb ≥ 12) | 9 (23.1) | 9 (39.1) | 23 (56.1) | |

| PTH (pmol/L) | 20.4 (15.0-33.0) | 11.1 (7.5-25.9) | 20.4 (11.3-28.2) | 0.0634 |

| Calcium (mmol/L) | 2.06 (1.90-2.15) | 2.03 (1.90-2.31) | 2.11 (1.96-2.22) | 0.3066 |

| Phosphate (mmol/L) | 1.41 (1.28-1.64) | 1.50 (1.23-1.96) | 1.47 (1.26-1.73) | 0.9176 |

| Total protein (g/L) | 58.0 (51.0-67.0) | 58.0 (51.2-66.0) | 64.0 (56.0-75.0) | 0.1400 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 30.0 (26.0-33.0) | 27.5 (23.8-32.0) | 31.0 (27.0-37.0) | 0.1404 |

| Proteinuria = yes > 3.5 g/day | 21.0 (47.7) | 10.0 (22.7) | 13.0 (29.5) | |

| Proteinuria = no < 3.5 g/day | 16.0 (30.2) | 12.0 (22.6) | 25.0 (47.2) | |

| Proteinuria, median (IQR) | 4.6 (2.2-7.8) | 3.3 (0.8-7.0) | 2.1 (0.9-5.0) | 0.1859 |

| Indication for biopsy | 0.0243 | |||

| Sudden renal decline | 12 (30.8) | 12 (52.2) | 24 (58.5) | |

| Proteinuria rise | 20 (51.3) | 7 (30.4) | 7 (17.1) | |

| Systemic markers | 2 (5.1) | 1 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Hematuria (Indication) | 5 (12.8) | 3 (13.0) | 10 (24.4) | |

| Hematuria presence | 0.2809 | |||

| Present | 27 (69.2) | 17 (73.9) | 23 (56.1) | |

| Absent | 12 (30.8) | 6 (26.1) | 18 (43.9) | |

| Total glomeruli count | 19.0 (12.0-28.0) | 18.0 (10.5-32.5) | 10.0 (8.0-17.0) | 0.0154 |

| Global sclerosis (count) | 5.0 (2.0-11.0) | 4.0 (2.2-5.8) | 2.0 (1.0-3.2) | 0.0007 |

| Global sclerosis ratio | 0.3 (0.1-0.6) | 0.2 (0.1-0.4) | 0.1 (0.1-0.4) | 0.0212 |

| Segmental sclerosis (count) | 3.0 (0.5-6.0) | 1.0 (0.0-5.0) | 1.0 (0.0-2.5) | 0.0399 |

| Segmental sclerosis ratio | 0.1 (0.0-0.2) | 0.0 (0.0-0.2) | 0.0 (0.0-0.2) | 0.6571 |

| Crescent presence | 0.0567 | |||

| Present | 0 (0,0) | 5 (21.7) | 5 (12.2) | |

| Absent | 39 (100) | 18 (78.3) | 36 (87.8) | |

| IFTA presence (≥ 25) | 0.0073 | |||

| Present | 16 (41.0) | 17 (77.3) | 23 (69.7) | |

| Not present | 23 (59.0) | 5 (22.7) | 10 (30.3) | |

| IFTA severity score | 0.0019 | |||

| Absent < 10 | 5 (12.8) | 2 (9.1) | 3 (9.1) | |

| Mild 10-24 | 11 (28.2) | 15 (68.2) | 20 (60.6) | |

| Moderate 25-50 | 13 (33.3) | 5 (22.7) | 10 (30.3) | |

| Severe > 50 | 10 (25.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.0-2.5) | 1.0 (1.0-1.0) | 1.0 (1.0-2.0) | |

| Arteriosclerosis presence | 0.2367 | |||

| Present | 19 (50.0) | 9 (42.9) | 10 (71.4) | |

| Absent | 19 (50.0) | 12 (57.1) | 4 (28.6) | |

| Arteriosclerosis severity (0-3) | 0.2508 | |||

| None | 19 (50.0) | 12 (57.1) | 4 (28.6) | |

| Mild 25 | 6 (15.8) | 4 (19.0) | 7 (50.0) | |

| Moderate 26-50 | 9 (23.7) | 3 (14.3) | 2 (14.3) | |

| Severe > 50 | 4 (10.5) | 2 (9.5) | 1 (7.1) | |

| Arteriosclerosis median (IQR) | 0.5 (0.0-2.0) | 0.0 (0.0-1.0) | 1.0 (0.2-1.0) | |

| Hyalinosis severity (0-3) | 0.3221 | |||

| None | 8 (20.5) | 6 (28.6) | 4 (22.2) | |

| Mild | 15 (38.5) | 10 (47.6) | 10 (55.6) | |

| Moderate | 15 (38.5) | 3 (14.3) | 4 (22.2) | |

| Severe | 1 (2.6) | 2 (9.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Hyalinosis median (IQR) | 1.0 (1.0-2.0) | 1.0 (0.0-1.0) | 1.0 (1.0-1.0) | |

| Podocyte effacement | 0.0042 | |||

| Diffuse > 50 | 10 (26.3) | 6 (30.0) | 13 (52.0) | |

| Focal ≤ 50 | 3 (7.9) | 4 (20.0) | 9 (36.0) | |

| None | 2 (5.3) | 1 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Not reported | 23 (60.5) | 9 (45.0) | 3 (12.0) | |

| Podocyte effacement median (IQR) | 4.0 (1.2-4.0) | 2.5 (1.0-4.0) | 1.0 (1.0-2.0) | |

| ANA (antinuclear antibodies) | 0.5140 | |||

| Positive | 5 (13.5) | 4 (20.0) | 8 (24.2) | |

| Negative | 32 (86.5) | 16 (80.0) | 25 (75.8) | |

| Anti-dsDNA Antibodies | 0.3852 | |||

| Positive | 0 (0.0) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (4.2) | |

| Negative | 18 (94.7) | 7 (87.5) | 23 (95.8) | |

| C3 complement (low vs normal) | 0.1198 | |||

| Low | 0 (0.0) | 4 (33.3) | 7 (19.4) | |

| Normal | 11 (100.0) | 8 (66.7) | 29 (80.6) | |

| C4 complement (low vs normal) | 0.6700 | |||

| Low | 1 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (5.6) | |

| Normal | 23 (95.8) | 14 (100.0) | 34 (94.4) | |

| C-ANCA (cytoplasmic ANCA) | 0.6378 | |||

| Positive | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Negative | 35 (100) | 16 (100.0) | 15 (100.0) | |

| P-ANCA (perinuclear ANCA) | 1.0000 | |||

| Positive | 0 (0.0) | 1(6.25) | (0.0) | |

| Negative | 35 (100.0) | 15 (93.75) | 14 (100.0) | |

| Kidney failure (as per study definition) | 38 (97.4) | 15(65.2) | 25 (61.0) | 0.0002 |

| Mortality | 0.2038 | |||

| Yes | 8 (20.5) | 7 (30.4) | 5 (12.2) | |

| No | 31 (79.5) | 16 (69.6) | 36 (87.8) |

A clinical and laboratory-based logistic regression model was used to differentiate NDKD from DKD. We identified several clinical predictors that were independently associated with NDKD vs DKD. Nephrotic-range proteinuria (> 3.5 g/day) was significantly less common in NDKD [OR = 0.02, 95 % confidence interval (CI): 0.00-0.22, P = 0.0015]. Anemia (hemoglobin < 12 g/dL) was markedly more common in NDKD (OR = 9.56, 95%CI: 1.68-54.30, P = 0.0107). The presence of diabetic retinopathy was strongly associated with DKD and was significantly less common in NDKD (OR = 0.04, 95%CI: 0.00-0.38, P = 0.0067). Similarly, a diabetes duration of ≥ 10 years was rare among NDKD cases (OR = 0.01, 95%CI: 0.00-0.12, P = 0.0002). Furthermore, serum creatinine levels greater than 180 μmol/L were more frequently observed in NDKD (OR = 18.68, 95%CI: 2.26-154.80, P = 0.0063). Although podocyte effacement was more common with NDKD in univariate analysis, logistic regression comparing NDKD to DKD revealed that podocyte effacement was significantly less likely in NDKD (OR = 0.06, 95%CI: 0.01-0.39, P = 0.0033). This suggests that, after adjustment for other factors, podocyte injury remains more characteristic of DKD. The global sclerosis ratio did not differ significantly between groups (OR = 0.13, 95%CI: 0.01-3.21, P = 0.2108). Moderate and severe IFTA showed a borderline association with NDKD (OR = 0.22, 95%CI: 0.04-1.26, P = 0.0893).

When comparing mixed lesions (DKD + NDKD) to pure DKD, most clinical predictors of NDKD were not found to be significantly associated with the presence of mixed pathology. We found that only diabetes duration ≥ 10 years was significantly related to mixed lesions (OR = 0.07, 95%CI: 0.01-0.71, P = 0.0249). This suggests that long-standing diabetes may be prone to developing dual pathology. Moreover, we found that age was a significant predictor (OR = 1.13, 95%CI: 1.04-1.23, P = 0.0055) for the mixed lesions. This implies that older individuals may be more likely to have superimposed non-diabetic changes. Table 4 shows the predictors of NDKD vs DKD, as determined through logistic regression analysis.

| Group | Predictor | OR (95%CI) | P value | Significance |

| A clinical + lab-based model | ||||

| NDKD vs DKD | Proteinuria > 3.5 g/day | 0.02 (0.00-0.22) | 0.0015 | Significant |

| Haemoglobin < 12 g/dL | 9.56 (1.68-54.30) | 0.0107 | Significant | |

| Retinopathy present | 0.04 (0.00-0.38) | 0.0067 | Significant | |

| DM duration ≥ 10 years | 0.01 (0.00-0.12) | 0.0002 | Significant | |

| Age | 1.01 (0.94-1.08) | 0.8127 | Not significant | |

| Creatinine > 180 μmol/L | 18.68 (2.26-154.80) | 0.0063 | Significant | |

| Mixed vs DKD | Proteinuria > 3.5 g/day | 0.66 (0.08-5.70) | 0.7030 | Not significant |

| Haemoglobin < 12 g/dL | 1.90 (0.31-11.51) | 0.4850 | Not significant | |

| Retinopathy present | 0.35 (0.05-2.58) | 0.3049 | Not significant | |

| DM duration ≥ 10 years | 0.07 (0.01-0.71) | 0.0249 | Significant | |

| Age | 1.13 (1.04-1.23) | 0.0055 | Significant | |

| Creatinine > 180 μmol/L | 1.48 (0.13-16.50) | 0.7483 | Not significant | |

| A histopathological model | ||||

| NDKD vs DKD | Global sclerosis ratio | 0.13 (0.01-3.21) | 0.2108 | Not significant |

| Podocyte effacement | 0.06 (0.01-0.39) | 0.0033 | Significant | |

| IFTA moderate to severe | 0.22 (0.04-1.26) | 0.0893 | Borderline | |

| Mixed vs DKD | Global sclerosis ratio | 0.38 (0.04-3.73) | 0.4048 | Not significant |

| Podocyte effacement | 0.30 (0.08-1.19) | 0.0870 | Borderline | |

| IFTA moderate to severe | 0.19 (0.05-0.77) | 0.02 | Significant | |

Kaplan-Meier analysis identified significant differences in renal survival across the three groups (log-rank P = 0.0033). We compared Kaplan-Meier curves for DKD, mixed lesions, and NDKD, assessing time to kidney failure using eGFR at the time of biopsy as the starting point and kidney failure as the endpoint. Patients with NDKD showed the most favorable renal outcomes, with slower progression to kidney failure. The curve for DKD demonstrated the steepest decline in kidney function over time, suggesting that DKD carries the highest risk of progression. The mixed group (DKD + NDKD) exhibited intermediate survival, possibly indicating that treatment of superimposed pathology may slightly modify the natural course of diabetic kidney disease. Figure 3A shows Kaplan-Meier survival curves comparing time to kidney failure across the three groups.

We performed Cox regression analysis to identify predictors of kidney failure. Kidney failure was defined as a composite outcome of sustained eGFR < 20 mL/minute/1.73 m2, initiation of dialysis, or receipt of a kidney transplant. A Cox proportional hazards regression model was developed to identify predictors of progression to kidney failure among 72 patients with complete data. The model performed well (C-index = 0.93) and achieved strong statistical significance (log-rank χ2 = 106.9, P < 0.001). We observed that increasing age [hazard ratio (HR) 1.04, P = 0.01], higher serum creatinine at biopsy (HR = 1.01, P < 0.005), arteriosclerosis (HR = 1.56, P = 0.01), and moderate-to-severe IFTA (HR = 1.85, P < 0.005) were significantly associated with the development of kidney failure. Use of RAAS blockade was significantly protective (HR = 0.43, P = 0.02). Table 5 shows a multivariable Cox proportional hazards model for time to kidney failure and mortality.

| Variable | HR | 95%CI | P value | Significance |

| Multivariable Cox proportional hazards model (Kidney failure) | ||||

| Age | 1.04 | 1.01-1.07 | 0.01 | Significant |

| Creatinine | 1.01 | 1.01-1.01 | < 0.005 | Significant |

| RAS blocker (ACEi/ARBs) | 0.43 | 0.21-0.89 | 0.02 | Protective factor |

| Arteriosclerosis | 1.56 | 1.11-2.19 | 0.01 | Significant |

| IFTA | 1.85 | 1.26-2.72 | < 0.005 | Significant |

| Retinopathy | 1.60 | 0.79-3.25 | 0.19 | Not significant |

| Multivariable Cox proportional hazards model (Mortality) | ||||

| Age | 1.05 | 1.00-1.09 | 0.04 | Significant |

| Creatinine | 1.01 | 1.00-1.01 | < 0.005 | Significant |

| Hemoglobin < 12 g/dL | 2.25 | 0.66-7.72 | 0.20 | Not significant |

| Albumin < 30 g/L | 4.26 | 1.09-16.61 | 0.04 | Significant |

| Retinopathy | 3.66 | 1.05-12.72 | 0.04 | Significant |

| Arteriosclerosis | 2.47 | 1.36-4.50 | < 0.005 | Significant |

The Kaplan-Meier survival plot compared the time to death among three histologically defined groups: DKD, mixed, and NDKD, using eGFR at the time of biopsy as the time-to-event variable and mortality as the event. The log-rank test yielded a P-value of 0.018, indicating a statistically significant difference in mortality across the groups. Patients in the NDKD group exhibited the highest survival probability, indicating a lower risk of mortality over time. On the other side, the mixed group showed the worst survival outcomes, suggesting a higher mortality risk. The DKD group had an intermediate survival pattern, falling between the other two groups. These results highlight the prognostic value of biopsy-based classification. The presence of both diabetic and non-diabetic lesions may exhibit worse outcomes than either condition alone. Figure 3B shows the Kaplan-Meier survival plot comparing the time to death among three histologically defined groups using eGFR at the time of biopsy as the time-to-event variable and mortality as the event.

A multivariable Cox regression model was used to determine predictors of mortality. We found that older age (HR = 1.05, 95%CI: 1.00-1.09, P = 0.04), hypoalbuminemia (albumin < 30 g/L; HR = 4.26, 95%CI: 1.09-16.61, P = 0.04), diabetic retinopathy (HR = 3.66, 95%CI: 1.05-12.72, P = 0.04), and arteriosclerosis (HR = 2.47, 95%CI: 1.36-4.50, P < 0.005) were independently associated with increased mortality risk. Higher serum creatinine also significantly predicted mortality (HR = 1.01, 95%CI: 1.00-1.01, P < 0.005). Table 5 shows predictors of mortality in patients with diabetes who underwent a kidney biopsy.

We report the first detailed study based on kidney biopsy from Saudi Arabia. In this retrospective analysis, we found several pertinent findings. These findings add to the understanding of the different spectrum of kidney disease in diabetic patients. NDKD, either alone or mixed with diabetic lesions, was more common than DKD alone. Distinct clinical features helped to differentiate NDKD from DKD. These features included less proteinuria, shorter diabetes duration, and absence of retinopathy in cases of NDKD. NDKD was also associated with better renal and patient survival. Conversely, DKD and mixed pathologies were linked to worse outcomes, with histological and clinical factors such as arteriosclerosis and elevated creatinine independently predicting kidney failure and mortality.

Prior to our study, limited research had been conducted in Saudi Arabia. These studies were primarily descriptive, focusing solely on histopathologies with a small sample size[12,13]. The first study analyzed 16 biopsies and found NDKD in 50% of diabetic patients, with membranous glomerulonephritis and interstitial nephritis being most common[12]. Another study reported 10 patients with mixed lesions, identifying IgA nephropathy in five (50%), interstitial nephritis in two (20%), membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis in two (20%), and membranous nephropathy in one (10%)[13]. These studies provided important descriptive data but were limited by small sample sizes and purely descriptive designs. None explored predictors, outcomes, or comparative analysis between DKD and NDKD. Our study addresses these gaps by integrating clinical, pathological, and outcome data to provide a more comprehensive understanding. We searched for predictors of DKD that could differentiate it from NDKD and evaluated long-term outcomes using Cox regression and Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, approaches not previously addressed.

We found that NDKD alone or in combination with DKD was more common than isolated DKD. NDKD was seen in 39.8%, NDKD and DKD together in 22.3%, and DKD in 37.9%. FSGS was the predominant pathology (20.3%), followed by interstitial nephritis (18.2%), emphasizing the importance of kidney biopsy for accurate diagnosis. Clinicians should have a low threshold to biopsy diabetic patients with atypical presentations. Identifying the correct etiology of NDKD and providing appropriate therapy, along with optimal diabetes control, may improve outcomes. A narrative review reported that the prevalence of isolated NDKD ranges from 0 to 68.6% (average 40.6%) and diabetic nephropathy plus NDKD ranges from 0 to 45.5% (average 18.1%)[14]. There is also variability in predominant histopathological diagnoses. We found FSGS most common (20.3%), followed by interstitial nephritis (18.2%). Other studies similarly reported FSGS[15-17], while some found membranous[5] or acute tubular interstitial nephritis[18] as predominant. Such variability likely reflects differences in patient selection, biopsy indications, epidemiology, and diagnostic practices.

We identified several independent predictors distinguishing NDKD from DKD. Shorter diabetes duration (< 10 years) and absence of diabetic retinopathy were significantly associated with NDKD. Our findings align with prior literature showing that diabetic retinopathy indicates DKD, while its absence suggests NDKD[19-22]. However, biopsy-proven NDKD can still have diabetic retinopathy; in our cohort, 24.4% of NDKD had it. Conversely, only 59% of DKD and 39.1% of mixed lesions had retinopathy. Thus, 41% of DKD, 60.9% of mixed, and 75.6% of NDKD lacked retinopathy. The prevalence of retinopathy is higher in DKD, though 23.6% of biopsy-proven DKD may not have it[23]. Hence, retinopathy is predictive but not exclusive of DKD. Additionally, diabetes duration ≥ 10 years was uncommon in NDKD, suggesting that shorter duration indicates NDKD. Similar findings were reported in prior studies[18,22,24,25].

Nephrotic-range proteinuria was less common in NDKD compared to DKD, and this association remained robust in logistic regression. Prior studies also found higher proteinuria in DKD[26-28]. Liu et al[26] reported nephrotic-range proteinuria in 63.2% of DKD vs 42.3% in NDKD, while Lee et al[27] found 62.8% in DKD vs 24% in NDKD. In our study, median proteinuria was highest in DKD (4.6 g/day), followed by mixed (3.3 g/day), and lowest in NDKD (2.1 g/day). In practice, clinicians often biopsy diabetic patients with worsening renal function or high proteinuria to rule out NDKD. Although high proteinuria suggests NDKD, our findings indicate that marked proteinuria may still represent DKD. In such cases, additional features such as shorter diabetes duration, absence of retinopathy, or atypical findings (e.g., active urinary sediment or sudden nephrotic syndrome) should prompt consideration of NDKD. A thorough evaluation of these factors can guide diagnostic and management decisions.

Diabetic patients are more prone to anemia due to chronic inflammation, reduced erythropoietin production, and impaired oxygen sensing[29]. In univariate analysis, anemia was more severe in DKD, but multivariable analysis showed hemoglobin < 12 g/dL was independently associated with higher odds of NDKD. This discrepancy may result from confounding factors and differences in analyzing hemoglobin as continuous vs binary. Previous studies reported mixed findings; one found anemia, reduced RBC count, and low hemoglobin associated with NDKD on univariate analysis, but only RBC count remained significant on multivariate analysis[30], while another identified anemia as a DKD predictor[31]. These mixed results highlight the complex relationship between anemia and kidney pathology in diabetes and should be interpreted cautiously.

In multivariable regression, serum creatinine > 180 μmol/L was independently associated with higher odds of NDKD compared to DKD. This contrasts with another study identifying creatinine > 97 μmol/L as predictive of DKD[32]. The difference may reflect variations in patient populations and geography. Higher baseline creatinine in our NDKD group may relate to the diverse pathologies - interstitial nephritis, immune complex glomerulonephritis, FSGS, and lupus nephritis - often causing acute or rapidly progressive injury. Also, biopsies were more often performed in the NDKD group due to sudden renal decline (58.5% vs 30.8%), explaining higher creatinine levels. These findings suggest that, especially in populations with higher NDKD prevalence, elevated creatinine should not preclude biopsy, emphasizing individualized assessment over fixed thresholds.

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis for kidney failure revealed significant differences (log-rank P = 0.0033). DKD patients had the poorest renal survival and fastest progression, NDKD the best, and mixed lesions intermediate. Similar findings were reported in the CKD-Research of Outcomes in Treatment and Epidemiology cohort, where DKD patients had a 50% higher risk of eGFR decline (HR = 2.30) and kidney replacement therapy (HR = 1.64) compared to NDKD, with faster progression[33]. This indicates that diabetic nephropathy follows a more aggressive course than many non-diabetic renal pathologies, highlighting the prognostic significance of biopsy-based classification.

Predictors of kidney failure in our cohort included older age and higher serum creatinine, both independently associated with faster progression. Use of renin-angiotensin system (RAS) blockers was significantly protective. Histologically, arteriosclerosis and moderate-to-severe IFTA were strong predictors. These associations are biologically plausible; aging reduces nephron number and reserve, while comorbidities and altered immune responses increase vulnerability[34]. Higher creatinine may reflect advanced disease or concurrent NDKD. RAS blockers protect by lowering glomerular pressure and limiting fibrosis, with well-established efficacy in reducing proteinuria[35], slowing CKD progression, and reducing mortality[36,37].

Our cohort also showed significant mortality differences on Kaplan-Meier analysis. NDKD patients had the highest survival, mixed lesions the worst, and DKD intermediate. These results suggest histopathological diagnosis impacts both renal and patient survival. A Korean study similarly reported best survival in NDKD, worst in mixed, and intermediate in DKD[38]. Jin Kim Y et al[39] also found better survival in NDKD and intermediate outcomes in mixed pathology. Cox regression showed that increasing age, hypoalbuminemia, diabetic retinopathy, arteriosclerosis, and higher serum creatinine independently predicted mortality. Mortality in our cohort was multifactorial, reflecting poor physiological reserve with aging, malnutrition, inflammation, vascular damage, and impaired kidney function. A Spanish study found older age, peripheral vascular disease, higher creatinine, and DKD as mortality risk factors[40]. These findings underscore the importance of comprehensive clinical and pathological assessments to identify high-risk patients and plan interventions.

Our study has several strengths. It represents the first comprehensive biopsy-based analysis of diabetic patients with kidney disease from Saudi Arabia. Earlier local studies had small sample sizes and lacked clinical correlation. Our study integrated histopathological findings with clinical predictors and long-term outcomes using robust statistical models, including logistic regression and Cox analysis, enabling differentiation between DKD and NDKD and identification of predictors of kidney failure and mortality.

We acknowledge limitations. Being a single-center retrospective analysis, findings cannot be generalized and may be prone to referral bias. Since biopsies were performed based on clinical suspicion, selection bias toward atypical presentations is possible. Despite these limitations, our cohort provides valuable insights into the clinical-pathological presentation of DKD and NDKD in this underrepresented population. We recommend that future studies aim to validate our findings in larger, multicenter cohorts to improve generalizability. Future studies should also explore the utility of non-invasive biomarkers in differentiating DKD from NDKD, potentially reducing the need for biopsy. Finally, studies evaluating the impact of histology-guided treatment strategies on long-term renal and patient survival are needed.

NDKD and mixed lesions are common in patients with diabetes and often coexist with DKD. A shorter diabetes duration, absence of diabetic retinopathy, anemia, and elevated serum creatinine should prompt the clinician to consider NDKD and the need for a kidney biopsy. NDKD is associated with better renal survival and a lower risk of progression to kidney failure compared to DKD. Factors such as older age, higher serum creatinine at biopsy, arteriosclerosis, and moderate-to-severe interstitial fibrotic arteriopathy are independently associated with an increased risk of kidney failure. In contrast, RAS blockade has a protective effect. In terms of mortality, patients with NDKD had the best survival, while those with mixed lesions had the worst outcomes. Independent predictors of mortality included increasing age, hypoalbuminemia, diabetic retinopathy, arteriosclerosis, and elevated serum creatinine.

| 1. | NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in diabetes prevalence and treatment from 1990 to 2022: a pooled analysis of 1108 population-representative studies with 141 million participants. Lancet. 2024;404:2077-2093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 401] [Article Influence: 200.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Fenta ET, Eshetu HB, Kebede N, Bogale EK, Zewdie A, Kassie TD, Anagaw TF, Mazengia EM, Gelaw SS. Prevalence and predictors of chronic kidney disease among type 2 diabetic patients worldwide, systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2023;15:245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Aljulifi MZ. Prevalence and reasons of increased type 2 diabetes in Gulf Cooperation Council Countries. Saudi Med J. 2021;42:481-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Alshehri MA, Alkhlady HY, Awan ZA, Algethami MR, Al Mahdi HB, Daghistani H, Orayj K. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in Saudi Arabia: an epidemiological population-based study. BMC Nephrol. 2025;26:37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Souza DA, Silva GEB, Fernandes IL, de Brito DJA, Muniz MPR, Neto OMV, Costa RS, Dantas M, Neto MM. The Prevalence of Nondiabetic Renal Diseases in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus in the University Hospital of Ribeirão Preto, São Paulo. J Diabetes Res. 2020;2020:2129459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Grujicic M, Salapura A, Basta-Jovanovic G, Figurek A, Micic-Zrnic D, Grbic A. Non-Diabetic Kidney Disease in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus-11-Year Experience from a Single Center. Med Arch. 2019;73:87-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tervaert TW, Mooyaart AL, Amann K, Cohen AH, Cook HT, Drachenberg CB, Ferrario F, Fogo AB, Haas M, de Heer E, Joh K, Noël LH, Radhakrishnan J, Seshan SV, Bajema IM, Bruijn JA; Renal Pathology Society. Pathologic classification of diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:556-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 842] [Cited by in RCA: 1181] [Article Influence: 73.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2024;105:S117-S314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2185] [Article Influence: 1092.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gross JL, de Azevedo MJ, Silveiro SP, Canani LH, Caramori ML, Zelmanovitz T. Diabetic nephropathy: diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:164-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1037] [Cited by in RCA: 1144] [Article Influence: 54.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Sethi S, Haas M, Markowitz GS, D'Agati VD, Rennke HG, Jennette JC, Bajema IM, Alpers CE, Chang A, Cornell LD, Cosio FG, Fogo AB, Glassock RJ, Hariharan S, Kambham N, Lager DJ, Leung N, Mengel M, Nath KA, Roberts IS, Rovin BH, Seshan SV, Smith RJ, Walker PD, Winearls CG, Appel GB, Alexander MP, Cattran DC, Casado CA, Cook HT, De Vriese AS, Radhakrishnan J, Racusen LC, Ronco P, Fervenza FC. Mayo Clinic/Renal Pathology Society Consensus Report on Pathologic Classification, Diagnosis, and Reporting of GN. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:1278-1287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Liapis H, Gaut JP, Klein C, Bagnasco S, Kraus E, Farris AB 3rd, Honsova E, Perkowska-Ptasinska A, David D, Goldberg J, Smith M, Mengel M, Haas M, Seshan S, Pegas KL, Horwedel T, Paliwa Y, Gao X, Landsittel D, Randhawa P; Banff Working Group. Banff Histopathological Consensus Criteria for Preimplantation Kidney Biopsies. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:140-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Jalalah SM. Non-diabetic renal disease in diabetic patients. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2008;19:813-816. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Alrehaili AD, Almuraydhi KM, Al Essa MTA. Diabetic Nephropathy among Adult Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Saudi Arabia. Egypt J Hosp Med. 2018;70:554-558. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Tong X, Yu Q, Ankawi G, Pang B, Yang B, Yang H. Insights into the Role of Renal Biopsy in Patients with T2DM: A Literature Review of Global Renal Biopsy Results. Diabetes Ther. 2020;11:1983-1999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Nzerue CM, Hewan-Lowe K, Harvey P, Mohammed D, Furlong B, Oster R. Prevalence of non-diabetic renal disease among African-American patients with type II diabetes mellitus. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2000;34:331-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Pham TT, Sim JJ, Kujubu DA, Liu IL, Kumar VA. Prevalence of nondiabetic renal disease in diabetic patients. Am J Nephrol. 2007;27:322-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ingwiller M, Delautre A, Tivollier JM, Edet S, Florens N, Couchoud C, Hannedouche T; REIN registry. Kidney Biopsy-Proven Diabetic and Non-Diabetic Kidney Diseases and Outcomes in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Receiving Dialysis: The REIN Registry. Kidney Med. 2025;7:100944. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Prasad N, Veeranki V, Bhadauria D, Kushwaha R, Meyyappan J, Kaul A, Patel M, Behera M, Yachha M, Agrawal V, Jain M. Non-Diabetic Kidney Disease in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Changing Spectrum with Therapeutic Ascendancy. J Clin Med. 2023;12:1705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wang X, Li J, Huo L, Feng Y, Ren L, Yao X, Jiang H, Lv R, Zhu M, Chen J. Clinical characteristics of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetic mellitus manifesting heavy proteinuria: A retrospective analysis of 220 cases. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;157:107874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tone A, Shikata K, Matsuda M, Usui H, Okada S, Ogawa D, Wada J, Makino H. Clinical features of non-diabetic renal diseases in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2005;69:237-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Dong Z, Wang Y, Qiu Q, Zhang X, Zhang L, Wu J, Wei R, Zhu H, Cai G, Sun X, Chen X. Clinical predictors differentiating non-diabetic renal diseases from diabetic nephropathy in a large population of type 2 diabetes patients. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2016;121:112-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Popa O, Stefan G, Capusa C, Mandache E, Stancu S, Petre N, Mircescu G. Non-diabetic glomerular lesions in diabetic kidney disease: clinical predictors and outcome in an Eastern European cohort. Int Urol Nephrol. 2021;53:739-747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Liang S, Zhang XG, Cai GY, Zhu HY, Zhou JH, Wu J, Chen P, Lin SP, Qiu Q, Chen XM. Identifying parameters to distinguish non-diabetic renal diseases from diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Soni SS, Gowrishankar S, Kishan AG, Raman A. Non diabetic renal disease in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nephrology (Carlton). 2006;11:533-537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wilfred DC, Mysorekar VV, Venkataramana RS, Eshwarappa M, Subramanyan R. Nondiabetic Renal Disease in type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients: A Clinicopathological Study. J Lab Physicians. 2013;5:94-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Liu S, Guo Q, Han H, Cui P, Liu X, Miao L, Zou H, Sun G. Clinicopathological characteristics of non-diabetic renal disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in a northeastern Chinese medical center: a retrospective analysis of 273 cases. Int Urol Nephrol. 2016;48:1691-1698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lee YH, Kim KP, Kim YG, Moon JY, Jung SW, Park E, Kim JS, Jeong KH, Lee TW, Ihm CG, Jo YI, Choi HY, Park HC, Lee SY, Yang DH, Yi JH, Han SW, Lee SH. Clinicopathological features of diabetic and nondiabetic renal diseases in type 2 diabetic patients with nephrotic-range proteinuria. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e8047. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ghani AA, Al Waheeb S, Al Sahow A, Hussain N. Renal biopsy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: indications and nature of the lesions. Ann Saudi Med. 2009;29:450-453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Antoniadou C, Gavriilidis E, Ritis K, Tsilingiris D. Anemia in diabetes mellitus: Pathogenetic aspects and the value of early erythropoietin therapy. Metabol Open. 2025;25:100344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Zeng YQ, Yang YX, Guan CJ, Guo ZW, Li B, Yu HY, Chen RX, Tang YQ, Yan R. Clinical predictors for nondiabetic kidney diseases in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a retrospective study from 2017 to 2021. BMC Endocr Disord. 2022;22:168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ito K, Yokota S, Watanabe M, Inoue Y, Takahashi K, Himuro N, Yasuno T, Miyake K, Uesugi N, Masutani K, Nakashima H. Anemia in Diabetic Patients Reflects Severe Tubulointerstitial Injury and Aids in Clinically Predicting a Diagnosis of Diabetic Nephropathy. Intern Med. 2021;60:1349-1357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Sun Y, Ren Y, Lan P, Yu X, Feng J, Hao D, Xie L. Clinico-pathological features of diabetic and non-diabetic renal diseases in type 2 diabetic patients: a retrospective study from a 10-year experience in a single center. Int Urol Nephrol. 2023;55:2303-2312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Chen S, Chen L, Jiang H. Prognosis and risk factors of chronic kidney disease progression in patients with diabetic kidney disease and non-diabetic kidney disease: a prospective cohort CKD-ROUTE study. Ren Fail. 2022;44:1309-1318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 34. | Tang Y, Jiang J, Zhao Y, Du D. Aging and chronic kidney disease: epidemiology, therapy, management and the role of immunity. Clin Kidney J. 2024;17:sfae235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Lozano-Maneiro L, Puente-García A. Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System Blockade in Diabetic Nephropathy. Present Evidences. J Clin Med. 2015;4:1908-1937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Catapano F, Chiodini P, De Nicola L, Minutolo R, Zamboli P, Gallo C, Conte G. Antiproteinuric response to dual blockade of the renin-angiotensin system in primary glomerulonephritis: meta-analysis and metaregression. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52:475-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Hsu TW, Liu JS, Hung SC, Kuo KL, Chang YK, Chen YC, Hsu CC, Tarng DC. Renoprotective effect of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system blockade in patients with predialysis advanced chronic kidney disease, hypertension, and anemia. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:347-354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Tan J, Zwi LJ, Collins JF, Marshall MR, Cundy T. Presentation, pathology and prognosis of renal disease in type 2 diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2017;5:e000412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Jin Kim Y, Hyung Kim Y, Dae Kim K, Ryun Moon K, Ho Park J, Mi Park B, Ryu H, Eun Choi D, Ryang Na K, Sun Suh K, Wook Lee K, Tai Shin Y. Nondiabetic kidney diseases in type 2 diabetic patients. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2013;32:115-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Bermejo S, González E, López-Revuelta K, Ibernon M, López D, Martín-Gómez A, Garcia-Osuna R, Linares T, Díaz M, Martín N, Barros X, Marco H, Navarro MI, Esparza N, Elias S, Coloma A, Robles NR, Agraz I, Poch E, Rodas L, Lozano V, Fernández B, Hernández E, Martínez MI, Stanescu RI, Moirón JP, García N, Goicoechea M, Calero F, Bonet J, Galceran JM, Liaño F, Pascual J, Praga M, Fulladosa X, Soler MJ. Risk factors for non-diabetic renal disease in diabetic patients. Clin Kidney J. 2020;13:380-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/