Published online Dec 25, 2025. doi: 10.5527/wjn.v14.i4.111343

Revised: July 18, 2025

Accepted: October 30, 2025

Published online: December 25, 2025

Processing time: 178 Days and 21.5 Hours

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a severe complication of acute pancreatitis (AP) associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Early prediction of AKI remains a clinical challenge owing to the limitations of traditional biomarkers, such as serum creatinine.

To evaluate the concentration and predictive value of plasma neutrophil gelati

This cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted from October 2021 to June 2023 at Bach Mai Hospital. In total, 219 patients were enrolled, including 51 patients with AP and AKI, 168 patients with AP but without AKI, and 35 healthy controls. Plasma NGAL levels were measured and compared between groups. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis was performed to determine the predictive value of NGAL levels for the severity of AKI and AP.

Among AP and AKI cases, 47.1% were classified as Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes stage 1, 33.3% as stage 2, and 19.6% as stage 3. The AP with AKI group (570.9 ng/mL) had significantly higher median plasma NGAL concentrations than the AP without AKI group (400.6 ng/mL) and the healthy control group (234.3 ng/mL) (P < 0.01). The NGAL levels increased proportionally with AKI severity. A plasma NGAL cutoff value of 504.29 ng/mL predicted AKI with 60.8% sensitivity and 68.4% specificity (area under the curve = 0.684; P < 0.001). A cutoff of 486.03 ng/mL predicted AP severity with 66.1% sensitivity and 66.4% specificity (area under the curve = 0.651; P < 0.005). NGAL positively correlated with international normalized ratio, urea, creatinine, lactate dehydrogenase, and lactate levels.

Plasma NGAL levels predicted both AKI development and disease severity. Therefore, NGAL should be consi

Core Tip: Severe acute pancreatitis (AP) is frequently associated with multiple complications, including acute kidney injury (AKI). In clinical practice, the early diagnosis of AKI remains challenging. This study provides evidence of the value of plasma neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in predicting the occurrence of AKI, assessing the severity of AP, and forecasting the need for continuous renal replacement therapy in patients with AP complicated by AKI. Additionally, we analyzed the correlation between plasma neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin levels and clinical and paraclinical characteristics.

- Citation: Nguyen KT, Le NH, Le TV, Pham DT, Nguyen TA, Nguyen LC, Do SN. Concentration and predictive value of plasma neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in patients with acute pancreatitis and acute kidney injury. World J Nephrol 2025; 14(4): 111343

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-6124/full/v14/i4/111343.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5527/wjn.v14.i4.111343

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a common gastrointestinal emergency with an increasing global incidence of approximately 30-40 cases per 100000 individuals annually. The overall mortality rate ranges from 1% to 5%. Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a severe early complication of AP, occurring in approximately 15% of patients, and 69% of those with severe forms. AKI is associated with a high mortality rate ranging from 25% to 75%[1-5]. Early prediction of AKI remains challenging because serum creatinine, a conventional marker, typically increases only after a significant decline in glomerular filtration rate, potentially delaying therapeutic interventions[2,6].

Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) has emerged as a promising early biomarker of AKI. Preclinical studies demonstrate that NGAL levels increase in plasma and urine within hours following ischemic or toxic kidney injury[7-9]. NGAL has good-to-excellent predictive value for AKI based on area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) analyses[10,11]. However, data regarding the diagnostic and prognostic utility of plasma NGAL levels in AP-associated AKI remain limited. This study aimed to determine the plasma concentration of NGAL and assess its predictive value in patients with AP complicated by AKI.

This prospective longitudinal study with comparative analyses was conducted at Bach Mai Hospital, 103 Military Hospital, and 354 Military Hospital from October 2021 to June 2023. A total of 254 participants were enrolled and divided into three groups as follows: AP with AKI (AP-AKI) (study group), with 51 patients diagnosed with AP and AKI; AP without AKI (AP-non-AKI) group (control group) comprising 168 patients with AP but no evidence of AKI; and a healthy control group including 35 healthy individuals.

Inclusion criteria: The criteria for inclusion in the AP-AKI group were AP diagnosed according to the 2012 revised Atlanta criteria[1]; AKI diagnosed according to the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) 2012 criteria[2]; age ≥ 18 years; and provided informed consent for participation. For the AP-non-AKI group, the inclusion criteria were as follows: AP was diagnosed according to the 2012 revised Atlanta criteria[1]; no evidence of AKI; age ≥ 18 years; and provided informed consent for participation. For the healthy control group, the inclusion criteria were as follows: Age ≥ 18 years with normal health checkup results; age-and sex-matched AP patient groups; no history of kidney or urinary tract diseases; and provided informed consent for participation.

Diagnosis of AP: AP was diagnosed based on the 2012 revised Atlanta criteria[3], requiring the presence of at least two of the following three features: The acute onset of persistent severe epigastric pain often radiates to the back and is accom

Diagnosis of AKI: AKI was diagnosed and staged according to the KDIGO 2012 criteria[2].

Exclusion criteria: The criteria for exclusion from the AP-AKI and AP-non-AKI groups were a history of chronic kidney disease and patient or relative refusal to participate. For the healthy control group, the exclusion criterion was the presence of acute infectious diseases (e.g., viral and respiratory infections). Any patient or family withdrawing from the study and insufficient blood samples for plasma and urine NGAL testing as per the study design, or loss of samples during storage, were the general exclusion criteria.

Research design: A cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted to compare the AP-AKI, AP-non-AKI, and healthy control groups.

Sample size and sampling method: A convenience sampling method was utilized for patient recruitment.

Implementation protocol: Patients admitted to the participating hospitals were examined, diagnosed, treated, and monitored according to the established AP protocols, including fluid and electrolyte management, pain control, suppression of pancreatic secretion, nutritional support, complication monitoring, and hemodiafiltration or plasma exchange, if necessary. Blood samples were collected for hematological and biochemical analyses, including the quantification of plasma NGAL. Abdominal CT tomography was performed to assess AP severity using the Balthazar scale.

NGAL testing: Plasma NGAL levels were determined using the NGAL sandwich-direct enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay test kit (United States) at the Department of Pathophysiology, Military Medical Academy. Venous blood samples for plasma NGAL were collected within the first 24 hours of hospital admission, prior to the initiation of renal replacement therapy.

Research objectives: The study aimed to investigate: Demographic characteristics (age and sex) and AKI incidence by AP stage; CT imaging characteristics in patients with AP; changes in plasma NGAL concentration across the study groups; correlations between plasma NGAL concentration and various characteristics of AP; and predictive value of plasma NGAL levels for AKI development and severity in patients with AP. ROC curves were constructed, and the AUC was calculated to determine the optimal cut-off points, sensitivity, and specificity for AKI prediction.

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Bach Mai Hospital (No. 3094/BVBM-HDDD/2021).

Categorical data are presented as frequencies and percentages and were compared using the χ2 test. Continuous variables are reported as medians (interquartile ranges) or means ± SD, as appropriate. The normality of the variable distributions was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Differences between groups for continuous variables were analyzed using the t-test or Whitney’s test. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used to assess the correlations between plasma NGAL levels (due to its non-normal distribution) and the selected variables. The diagnostic utility of NGAL as a predictor of AKI was evaluated using ROC analysis and AUC. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were determined. Optimal cutoff points were identified using Youden’s index (J) to maximize the differentiation capability by assigning equal weights to sensitivity and specificity. All statistical analyses were performed using the IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software (version 22.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, United States). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Between October 2021 and June 2023, 219 patients with AP were recruited from the Bach Mai Hospital, 103 Military Hospital, and 354 Military Hospital. The patients were categorized into group 1 (AP with AKI), comprising 51 patients (23.3% of the total AP cohort). The majority were men (n = 45, 88.2%), with women accounting for six cases (11.8%). Meanwhile, group 2 (AP without AKI) included 168 patients (76.7% of the total AP cohort), including 135 men (80.4%) and 33 women (19.6%).

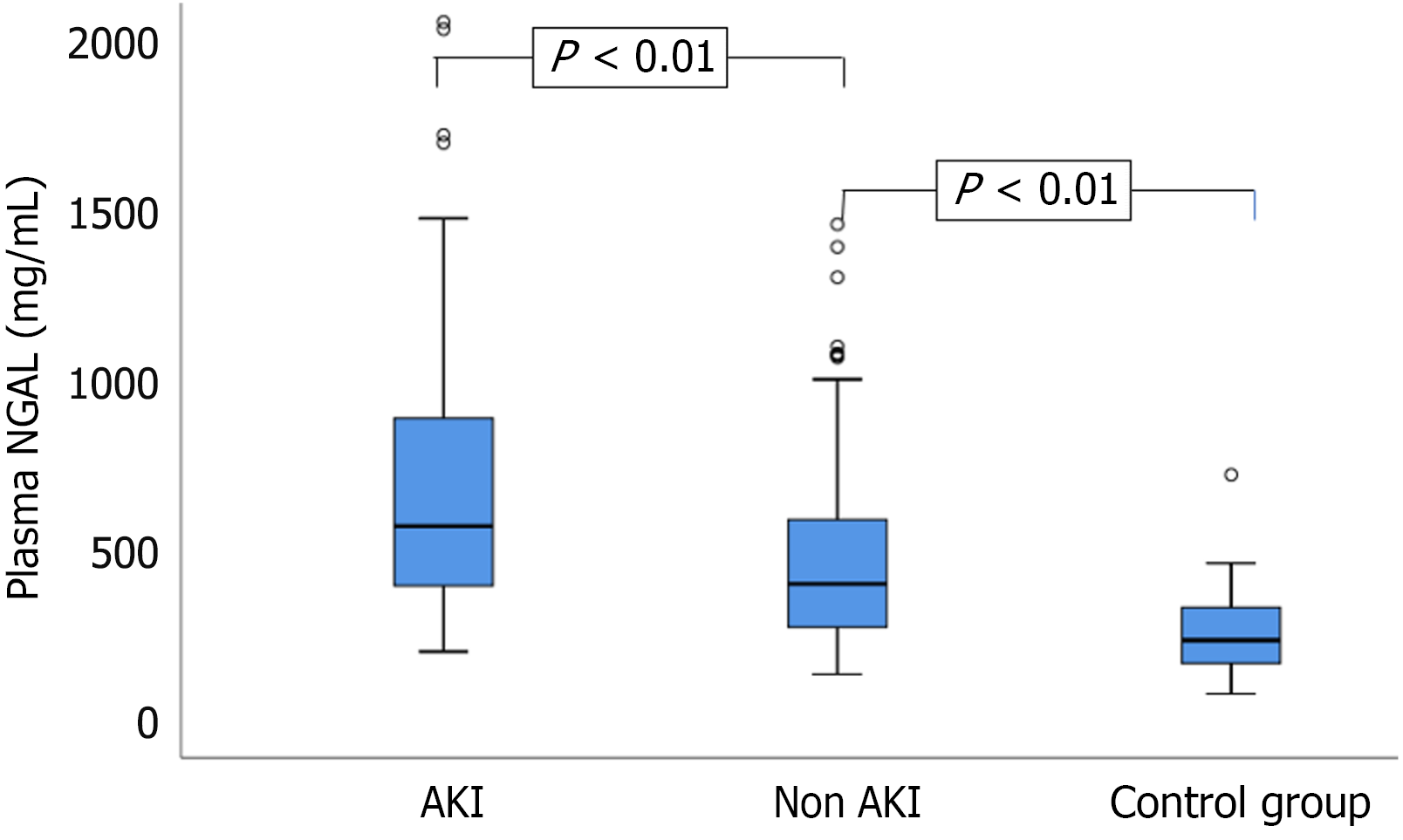

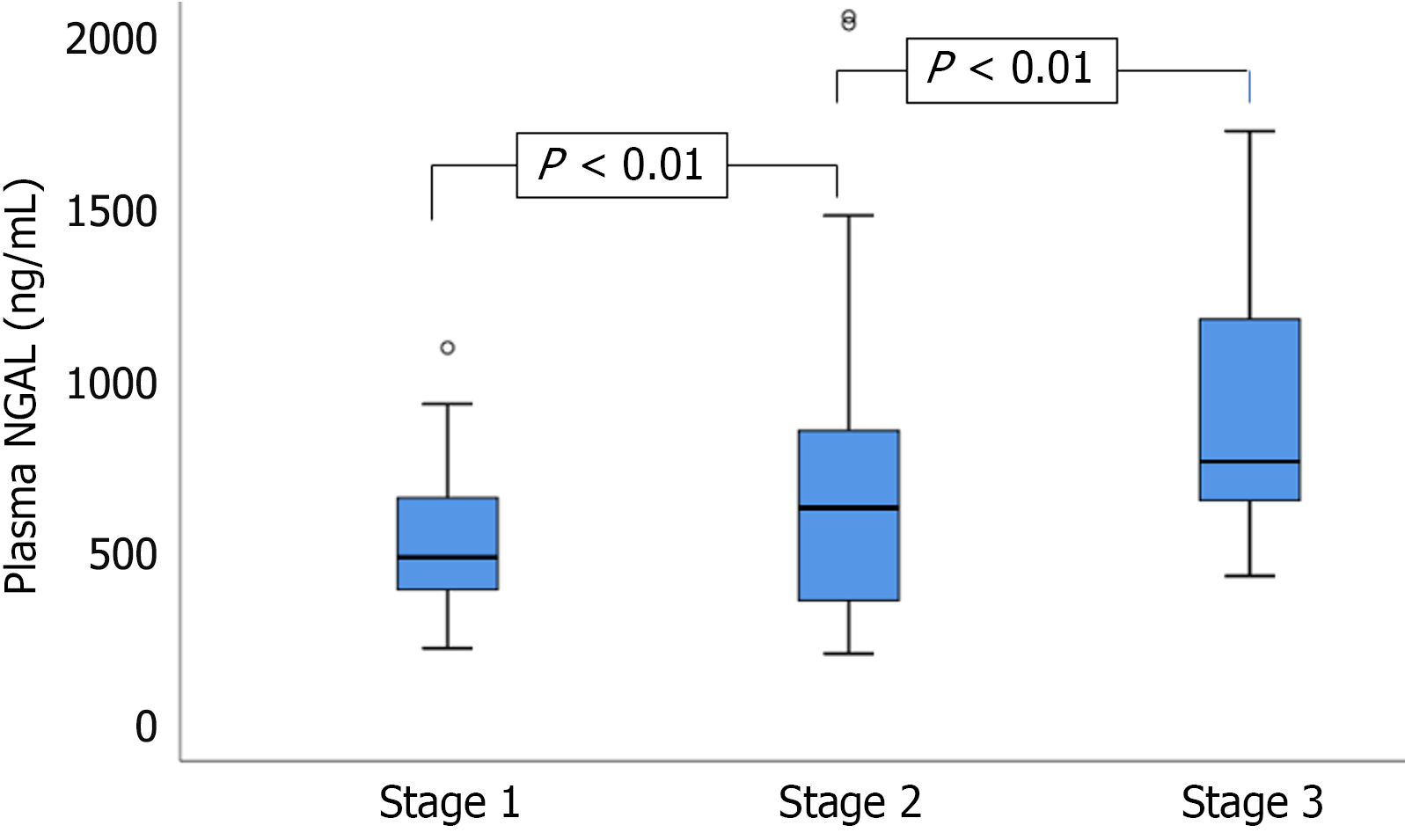

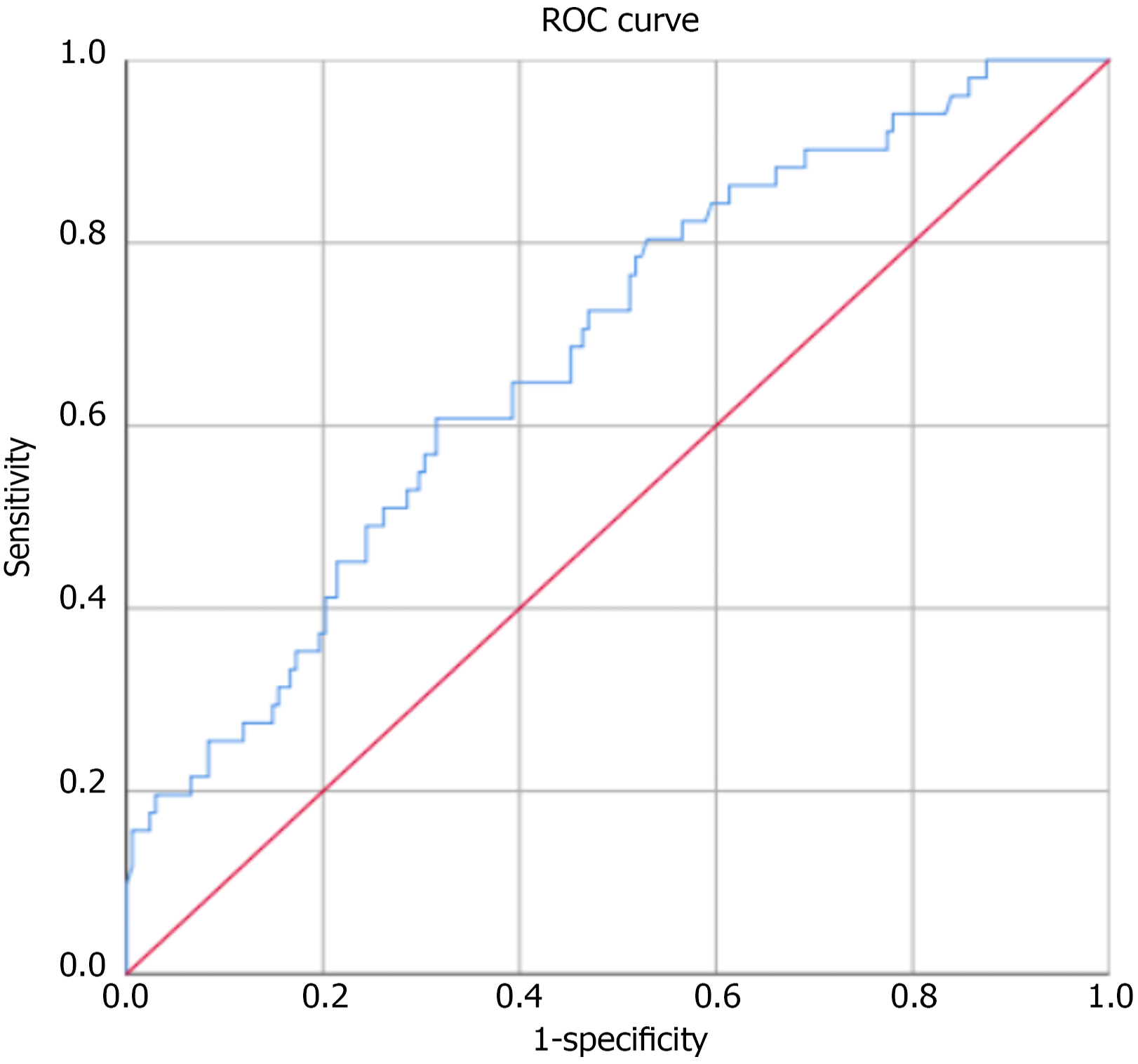

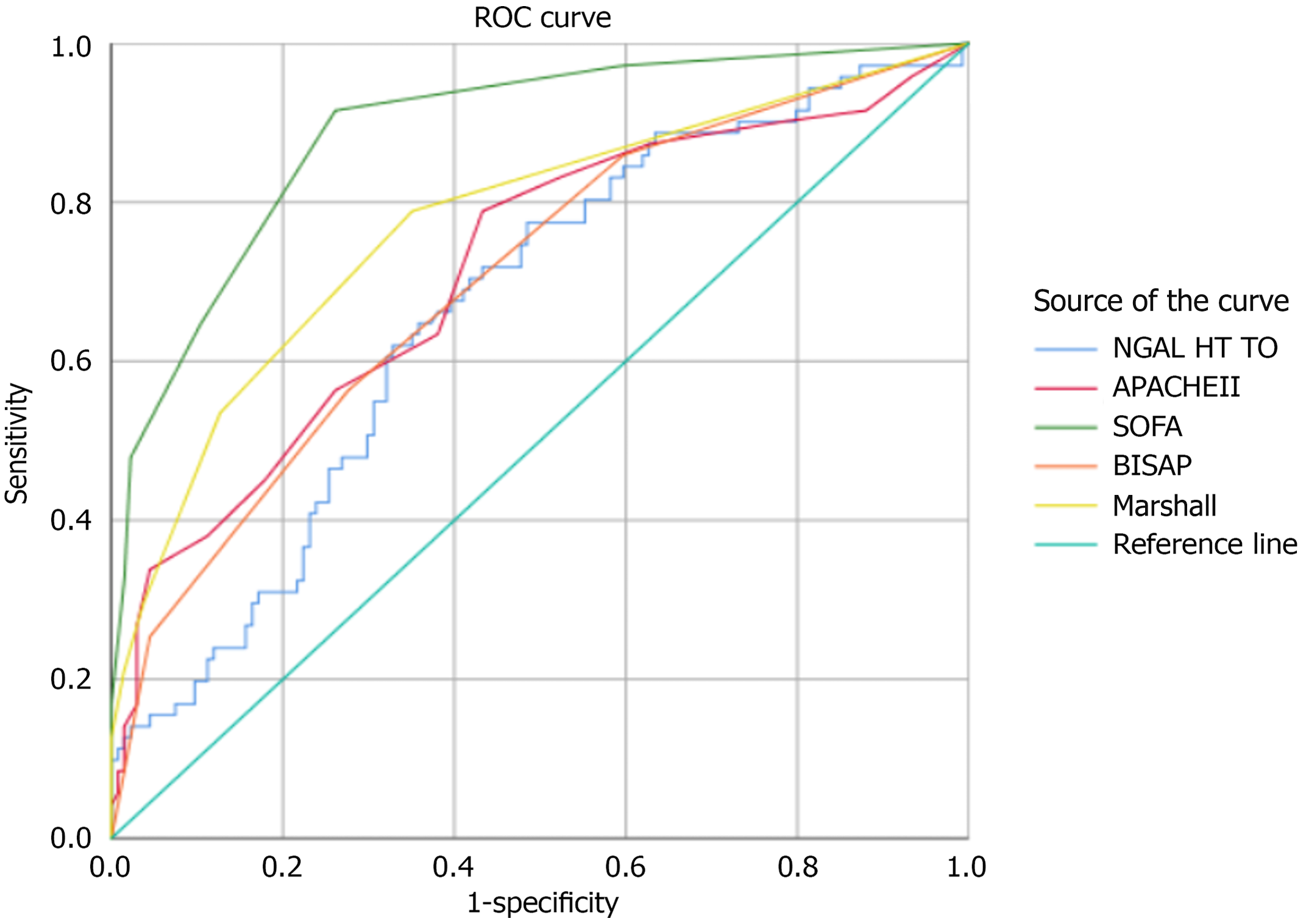

Additionally, 35 healthy individuals served as controls. The mean age in the AP-AKI group was 47.78 ± 14.5 years, whereas that in the AP-non-AKI group was 45.25 ± 12.7 years. Among the 51 patients with AP who developed AKI, the distribution across KDIGO stages was as follows: 24 patients (47.1%) had stage 1 AKI, 17 patients (33.3%) had stage 2 AKI, and 10 patients (19.6%) had stage 3 AKI. Comparison of plasma NGAL concentrations between study groups (n = 257) (Figure 1). Comparison of plasma NGAL levels between stages (Figure 2). The AUC shows the diagnostic performance of plasma NGAL (Figure 3). Comparison of the value of plasma NGAL with the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II, the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, the Bedside Index of Severity in Acute Pancreatiti, and Marshall scores in predicting the severity of AP (n = 219) (Figure 4).

The mean age of patients with AP and AKI was 47.78 ± 14.5 years, which was not significantly higher than that of patients without AKI (45.25 ± 12.7 years). No significant differences in the distribution of patients by age group. This distribution is consistent with the demographic structure of the Vietnamese population, in which individuals aged 20-60 years constitute the primary working age group. Dietary patterns of high meat and alcohol consumption, which are prevalent in this age group, are contributing factors to the development of AP. In addition, parasitic infections and gallstone disease remain common in tropical countries, such as Vietnam. The increasing prevalence of metabolic disorders, especially hypertriglyceridemia, also contributes significantly to the etiology of AP[4,5].

These findings are consistent with those of previous studies. For example, Yuan and Jin[6] reported in 2023 a similar mean age of 48.09 ± 7.86 years among patients with AP. By contrast, Uğurlu and Tercan[7] observed a significantly higher mean age in the AKI group (66.74 ± 19.39 years) than in the non-AKI group (55.54 ± 19.05 years, P < 0.0001). Similarly, Wu et al[8] have reported that patients with AP and AKI were significantly older than those without AKI, with mean ages of 61.68 and 55.12 years, respectively (P < 0.001). According to Ranson’s criteria, age > 55 years is a known risk factor for increased AP severity and mortality. In our study, 35.2% of patients were aged > 55 years[9].

The male-to-female ratio was markedly higher in both study groups: 7.5:1 in the AP-with-AKI group and 4.1:1 in the AP-without-AKI group. This trend aligns with that demonstrated in the existing literature, which suggests that alcohol-induced AP is more prevalent in men, whereas gallstone-related AP is more common in women. Our results are consistent with those of both national and international studies. For instance, the proportions of men were 82.3%, 65.6%, and 61.5% in previous studies[10-12]. Qu et al[11] also identified a statistically significant difference in sex distribution between AKI and non-AKI groups (P = 0.005).

Of 219 patients enrolled in this study, 51 (23.3%) developed AKI. The distribution according to AKI stage (KDIGO 2012 criteria) was as follows: Stage 1, 47.1%; stage 2, 33.3%; and stage 3, 19.6%. These findings are consistent with those of Lin et al[12], who have reported an AKI rate of 23.8%. However, our results were lower than those of Li et al[13] in China, who observed an overall AKI rate of 44.9%, with a peak incidence at 24 hours post-admission. In a 2023 study by Wu et al[8], the incidence of AKI was high at 62.5% in 799 patients with AP in the intensive care unit. Yuan and Jin[6] have reported an AKI incidence of 31.25% in 80 patients.

The severity of AP is closely correlated with the extent of multi-organ dysfunction[14]. The pathophysiology of AKI in patients with AP is primarily driven by inflammatory responses that lead to systemic vasodilation, renal hypoperfusion, and ischemic injury. This cascade increases plasma NGAL concentrations, which reflect early renal tubular injury[15-19]. In our cohort, median plasma NGAL levels were significantly higher in the AP with AKI group (570.9 ng/mL) than in the AP without AKI group (400.6 ng/mL) and healthy controls (234.3 ng/mL), with P < 0.01 for both comparisons. Plasma NGAL levels also increased progressively with AKI stage: 481.6 ng/mL (stage 1), 625.5 ng/mL (stage 2),

NGAL, a lipocalin protein secreted by injured renal tubular cells, has emerged as a promising biomarker for early detection of AKI. Its expression is upregulated within hours of injury and remains elevated for days[6,18,21,22]. NGAL has shown predictive utility in cardiac surgery, sepsis, and critical illnesses[23-25]. In our study, a plasma NGAL cutoff of 504.29 ng/mL yielded a sensitivity of 60.8% and a specificity of 68.4% for predicting AKI (AUC = 0.684, P < 0.001). This is in line with findings by Yuan and Jin[6] (cutoff 95.71 ng/mL, AUC = 0.71, sensitivity 68%, specificity 67.3%), and Siddappa et al[20] (cutoff 790.9 ng/mL, sensitivity 64%, specificity 96%, AUC = 0.8, P = 0.012). Albert et al[24] have reported an even higher performance at a cutoff > 546 ng/mL (AUC = 0.86) in predicting renal replacement therapy. While the AUC of 0.684 suggests only modest predictive performance, NGAL still holds promise in clinical contexts where early identification of high-risk patients is valuable. Rather than serving as a definitive diagnostic marker, plasma NGAL may be better positioned as an early screening biomarker that prompts intensified monitoring or additional testing in patients with AP.

Moreover, emerging evidence supports the combined use of NGAL with other biomarkers, such as kidney injury molecule-1, cystatin C, or liver-type fatty acid-binding protein, to enhance diagnostic accuracy and risk stratification. Future studies may explore multi-biomarker panels or scoring systems that integrate NGAL levels with clinical variables, which could offer improved sensitivity and specificity for the early detection of AP-AKI. For predicting AP severity, our NGAL cutoff of 486.03 ng/mL yielded an AUC of 0.651, with 66.1% sensitivity and 66.4% specificity (P < 0.005). In patients requiring continuous renal replacement therapy, NGAL (481.8 ng/mL achieved an AUC of 0.727 (sensitivity, 92.3%; specificity, 57.7%; P < 0.06). However, NGAL’s prognostic performance was lower than that of composite scoring systems such as APACHE II, the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, the Bedside Index of Severity in Acute Pancreatiti, and Marshall, which incorporate multiple clinical parameters[9,26-29]. Our results are consistent with those of Chauhan, who found AUCs of 0.864 and 0.863 for the Imrie and APACHE II scores, respectively[26].

Several factors may explain the variability in NGAL’s predictive performance for AKI across different studies. First, methodological differences such as study design (prospective vs retrospective), sample size, and single-center vs multicenter settings can significantly influence biomarker accuracy. Second, the type of NGAL assay used (e.g., enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay vs point-of-care platforms), along with variations in defined cutoff thresholds, can result in divergent sensitivity and specificity estimates. Third, the timing of NGAL measurement differs among studies-some assess levels within 2-6 hours of admission, while others use later time points-thus affecting its early predictive value.

Additionally, heterogeneity in patient populations, including differences in baseline renal function, disease severity, and comorbidities such as diabetes or sepsis, may impact NGAL expression and its association with AKI outcomes. Importantly, studies also vary in their criteria for defining AKI (e.g., KDIGO vs the risk, injury, failure, loss, end-stage kidney disease vs acute kidney injury network), further complicating cross-study comparisons. Lastly, the presence or absence of multivariate models that integrate NGAL with other biomarkers or clinical indicators can markedly influence reported performance metrics, including the AUC. In light of these factors, the AUC of 0.684 observed in our study, although modest, is consistent with findings from other clinical settings and supports the notion that NGAL may serve best as part of a multi-marker panel or early screening tool, rather than as a standalone diagnostic test.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, it was conducted at a single center, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings to broader patient populations. Second, the sample size was relatively small, potentially limiting the statistical power to detect subtle associations or conduct robust subgroup analyses. Third, we only evaluated plasma NGAL levels without assessing other potentially complementary biomarkers such as urinary NGAL, kidney injury molecule-1, or cystatin C. Fourth, NGAL concentrations were measured at a single time point within 24 hours of admission, which does not account for the potential diagnostic value of temporal trends or serial measurements. Lastly, despite adjustments for common confounders, unmeasured variables may still have influenced both NGAL levels and the risk of AKI, introducing the possibility of residual confounding.

This study evaluated the plasma NGAL concentrations in three groups: Patients with AP with AKI, patients with AP without AKI, and healthy controls. Among the patients with AP and AKI, 47.1% had stage 1 AKI, 33.3% had stage 2 AKI, and 19.6% had stage 3 AKI. Plasma NGAL levels were significantly higher in the AP with AKI group (570.9 ng/mL) than in the AP without AKI group (400.6 ng/mL) and healthy controls (234.3 ng/mL). Plasma NGAL levels increased pro

The authors sincerely thank the Board of Directors of the Military Medical Academy, the A9 Emergency Center, the Intensive Care Center, the Gastroenterology and Hepatology Center of Bach Mai Hospital, the Board of Directors of 354 Military Hospital, the Department of Gastroenterology and Hematology, 354 Military Hospital, the Department of Pathophysiology, Military Medical Academy, and all the patients, their families, friends, and colleagues who generously supported the completion of this study.

| 1. | Colvin SD, Smith EN, Morgan DE, Porter KK. Acute pancreatitis: an update on the revised Atlanta classification. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2020;45:1222-1231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Khwaja A. KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for acute kidney injury. Nephron Clin Pract. 2012;120:c179-c184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1436] [Cited by in RCA: 3708] [Article Influence: 264.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4932] [Cited by in RCA: 4719] [Article Influence: 363.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (48)] |

| 4. | Yang AL, McNabb-Baltar J. Hypertriglyceridemia and acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2020;20:795-800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 37.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Munoz MA, Sathyakumar K, Babu BA. Acute pancreatitis secondary to hypertriglyceridemia. Cleve Clin J Med. 2020;87:742-750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yuan L, Jin X. Predictive Value of Serum NGAL and β2 Microglobulin in Blood and Urine amongst Patients with Acute Pancreatitis and Acute Kidney Injury. Arch Esp Urol. 2023;76:335-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Uğurlu ET, Tercan M. The role of biomarkers in the early diagnosis of acute kidney injury associated with acute pancreatitis: Evidence from 582 cases. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2022;29:81-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wu S, Zhou Q, Cai Y, Duan X. Development and validation of a prediction model for the early occurrence of acute kidney injury in patients with acute pancreatitis. Ren Fail. 2023;45:2194436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ong Y, Shelat VG. Ranson score to stratify severity in Acute Pancreatitis remains valid - Old is gold. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;15:865-877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Garret C, Péron M, Reignier J, Le Thuaut A, Lascarrou JB, Douane F, Lerhun M, Archambeaud I, Brulé N, Bretonnière C, Zambon O, Nicolet L, Regenet N, Guitton C, Coron E. Risk factors and outcomes of infected pancreatic necrosis: Retrospective cohort of 148 patients admitted to the ICU for acute pancreatitis. United European Gastroenterol J. 2018;6:910-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Qu C, Gao L, Yu XQ, Wei M, Fang GQ, He J, Cao LX, Ke L, Tong ZH, Li WQ. Machine Learning Models of Acute Kidney Injury Prediction in Acute Pancreatitis Patients. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2020;2020:3431290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lin HY, Lai JI, Lai YC, Lin PC, Chang SC, Tang GJ. Acute renal failure in severe pancreatitis: A population-based study. Ups J Med Sci. 2011;116:155-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Li H, Qian Z, Liu Z, Liu X, Han X, Kang H. Risk factors and outcome of acute renal failure in patients with severe acute pancreatitis. J Crit Care. 2010;25:225-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zerem E, Kurtcehajic A, Kunosić S, Zerem Malkočević D, Zerem O. Current trends in acute pancreatitis: Diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29:2747-2763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 28.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (15)] |

| 15. | Boxhoorn L, Voermans RP, Bouwense SA, Bruno MJ, Verdonk RC, Boermeester MA, van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG. Acute pancreatitis. Lancet. 2020;396:726-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 276] [Cited by in RCA: 689] [Article Influence: 114.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zhang M, Pang M. Early prediction of acute respiratory distress syndrome complicated by acute pancreatitis based on four machine learning models. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2023;78:100215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lee DW, Cho CM. Predicting Severity of Acute Pancreatitis. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022;58:787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Romejko K, Markowska M, Niemczyk S. The Review of Current Knowledge on Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin (NGAL). Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:10470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bhatia R, Muniyan S, Thompson CM, Kaur S, Jain M, Singh RK, Dhaliwal A, Cox JL, Akira S, Singh S, Batra SK, Kumar S. Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin Protects Acinar Cells From Cerulein-Induced Damage During Acute Pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2020;49:1297-1306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Siddappa PK, Kochhar R, Sarotra P, Medhi B, Jha V, Gupta V. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin: An early biomarker for predicting acute kidney injury and severity in patients with acute pancreatitis. JGH Open. 2019;3:105-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Matsa R, Ashley E, Sharma V, Walden AP, Keating L. Plasma and urine neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in the diagnosis of new onset acute kidney injury in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2014;18:R137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Son E, Cho WH, Jang JH, Kim T, Jeon D, Kim YS, Yeo HJ. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin as a prognostic biomarker of severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. Sci Rep. 2022;12:7909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Passov A, Petäjä L, Pihlajoki M, Salminen US, Suojaranta R, Vento A, Andersson S, Pettilä V, Schramko A, Pesonen E. The origin of plasma neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in cardiac surgery. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20:182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Albert C, Zapf A, Haase M, Röver C, Pickering JW, Albert A, Bellomo R, Breidthardt T, Camou F, Chen Z, Chocron S, Cruz D, de Geus HRH, Devarajan P, Di Somma S, Doi K, Endre ZH, Garcia-Alvarez M, Hjortrup PB, Hur M, Karaolanis G, Kavalci C, Kim H, Lentini P, Liebetrau C, Lipcsey M, Mårtensson J, Müller C, Nanas S, Nickolas TL, Pipili C, Ronco C, Rosa-Diez GJ, Ralib A, Soto K, Braun-Dullaeus RC, Heinz J, Haase-Fielitz A. Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin Measured on Clinical Laboratory Platforms for the Prediction of Acute Kidney Injury and the Associated Need for Dialysis Therapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;76:826-841.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Min JH, Lee H, Chung SJ, Yeo Y, Park TS, Park DW, Moon JY, Kim SH, Kim TH, Sohn JW, Yoon HJ. Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin for Predicting Intensive Care Unit Admission and Mortality in Patients with Pneumonia. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2020;250:243-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Chauhan R, Saxena N, Kapur N, Kardam D. Comparison of modified Glasgow-Imrie, Ranson, and Apache II scoring systems in predicting the severity of acute pancreatitis. Pol Przegl Chir. 2022;95:6-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Biyik M, Biyik Z, Asil M, Keskin M. Systemic Inflammation Response Index and Systemic Immune Inflammation Index Are Associated with Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Acute Pancreatitis? J Invest Surg. 2022;35:1613-1620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Chatterjee R, Parab N, Sajjan B, Nagar VS. Comparison of Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II, Modified Computed Tomography Severity Index, and Bedside Index for Severity in Acute Pancreatitis Score in Predicting the Severity of Acute Pancreatitis. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2020;24:99-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lambden S, Laterre PF, Levy MM, Francois B. The SOFA score-development, utility and challenges of accurate assessment in clinical trials. Crit Care. 2019;23:374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 377] [Cited by in RCA: 609] [Article Influence: 87.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/