Published online Dec 25, 2025. doi: 10.5527/wjn.v14.i4.109168

Revised: June 17, 2025

Accepted: September 17, 2025

Published online: December 25, 2025

Processing time: 229 Days and 22.8 Hours

Intradialytic hypotension (IDH) is a prevalent and critical complication of haemo

Core Tip: Intradialytic hypotension remains a critical complication in haemodialysis, lacking a universal definition and significantly impacting patient morbidity and mortality. This comprehensive review elucidates the complex interplay of its pathophysiology, diverse risk factors, and severe consequences. It critically evaluates current management strategies, highlighting the limitations of existing definitions and the need for individualised approaches. The review underscores the promise of emerging technologies like artificial intelligence for prediction and the importance of multidisciplinary care and patient education. Ultimately, it advocates for a unified definition and strategically directs future research to optimize prevention and treatment, thereby improving outcomes for this vulnerable population.

- Citation: Haddiya I, Simanjuntak GDFI, Ramdani S. Updates in the management of intradialytic hypotension: Emerging strategies and innovations. World J Nephrol 2025; 14(4): 109168

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-6124/full/v14/i4/109168.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5527/wjn.v14.i4.109168

Despite advancements in dialysis technologies, the substantial mortality linked to end-stage renal disease continues to pose a major challenge, as the majority of patients depend on haemodialysis (HD) for renal function replacement[1]. Intradialytic hypotension (IDH) is among the most frequent complications observed during HD, primarily driven by the aging dialysis population and the growing prevalence of coexisting conditions such as diabetes mellitus and heart failure (HF). The reported occurrence of IDH varies significantly, ranging between 8% and 40%, which can be attributed to variations in its definitions, research methodologies, and patient demographics, including age, rates of diabetes or cardiovascular disease (CVD), interdialytic weight changes (IDWG), body mass, and gender distribution[2,3]. Beyond causing considerable discomfort during dialysis, IDH is strongly associated with severe outcomes such as vascular access complications, cardiac events, organ damage, and heightened mortality rates[4]. A universal definition for IDH remains elusive, complicating its identification and treatment. Existing definitions often include criteria such as a blood pressure (BP) drop below a specific threshold, a significant intradialytic BP decline, patient-reported symptoms, or clinical interventions to restore blood volume[5]. Our review seeks to deliver a thorough analysis of IDH, focusing on its clinical importance, underlying mechanisms, risk factors, and management strategies while advocating for a unified definition and outlining a strategic path for future investigations.

IDH is a frequent complication of HD, associated with disabling symptoms, underdialysis, vascular access thrombosis, accelerated loss of renal function, cardiovascular events, and increased mortality[3]. However, establishing a precise and universally accepted definition of low BP during dialysis remains challenging. According to the 2005 guidelines of the National Kidney Foundation’s Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative, IDH is defined as a decrease in systolic BP (SBP) of at least 20 mmHg or in mean arterial pressure (MAP) of at least 10 mmHg, accompanied by symptoms[6]. The Japanese Society of Dialysis Therapy Guidelines, however, define IDH as a reduction in SBP of 30 mmHg and MAP of 10 mmHg in conjunction with clinical events and therapeutic interventions[7]. A major limitation of these definitions is the inconsistent collection of symptomatic and nursing intervention data, which often rely on subjective assessments. Consequently, many studies adopt operational criteria based on absolute drops in SBP (e.g., 20 mmHg, 30 mmHg, or 40 mmHg) or specific nadir thresholds (e.g., SBP < 90 mmHg, < 95 mmHg, or < 100 mmHg) to enhance objectivity[8].

The reported prevalence of IDH varies significantly depending on the definition used, study design, and population characteristics. A meta-analysis reported a global IDH prevalence of 31% among hospitalised patients, while lower rates ranging from 10.1% to 11.6% were observed in outpatient settings[3,9]. Similarly, intradialytic hypertension prevalence ranged from 11% to 57%, depending on the definition employed[10]. Several patient-related factors contribute to the risk of IDH, including diabetes, IDWG, female gender, and low body weight[11]. Intradialytic hypertension shares certain predictive factors such as diabetes, undernutrition, elevated IDWG, and prolonged dialysis vintage[10]. The global distribution of home HD practices further underscores these disparities, with prevalence ranging from 0 to 58.4 per million population, inversely correlated with the median age of patients undergoing renal replacement therapy[12].

IDH may occur in up to 93% of HD patients, and its frequency is influenced by age, comorbidities, and dialysis-related variables[13]. Older age and extended dialysis vintage have been independently linked to higher IDH risk, as have underlying conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and active malignancy[13-15]. Dialysis-specific factors-including low target dry weight, high ultrafiltration rates (UFR), and dialysate composition-also contribute to hypotensive episodes[13,16]. The clinical consequences of IDH extend beyond symptoms, with associations found between recurrent episodes and increased rates of mortality and intensive care unit transfers among patients with both chronic kidney disease (CKD) and acute kidney injury[14]. Addressing modifiable risk factors and adopting advanced dialysis technologies are essential strategies for reducing the frequency and severity of IDH[16].

The temporal dimension of IDH incidence has also been investigated. Studies reveal that the risk of IDH increases across the dialysis week, with the first session presenting the lowest risk and the third the highest[17,18]. Within sessions, the median onset of hypotension typically occurs between 120 minutes and 149 minutes[19]. Variables such as age, predialysis BP, and serum phosphorus levels have been identified as contributing factors[17]. Furthermore, early-onset IDH has been linked to poorer survival outcomes, underscoring the prognostic significance of the timing of IDH onset[19,20]. These observations suggest that clinical management should consider both the day of the week and intradialytic timing to optimize preventive strategies.

Environmental and seasonal factors have been examined in relation to other medical conditions, offering potential insights for IDH. While some studies noted seasonal trends in diseases such as insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and Guillain-Barré syndrome, findings have been inconsistent and often vary by region[21,22]. In oncology, studies of IDH-mutant gliomas and Hodgkin lymphoma have shown tumour progression and diagnosis patterns influenced by environmental exposures and seasonal clustering, reflecting a complex interplay between genetic predispositions and environmental triggers[23,24]. Although such seasonal effects have not been clearly established for IDH in dialysis, these comparative insights highlight the potential influence of broader ecological factors in disease expression and progression.

Comparative studies between single-centre and multi-centre settings yield mixed results in IDH prevalence analysis. For instance, a single-centre study in Oman reported IDH1 and IDH2 mutation rates of 6.6% and 4.9%, respectively, in acute myeloid leukaemia patients, while a larger multi-centre study showed mutation rates between 0.8% and 4.2% in chronic phases and 21.6% in blast phases of myeloproliferative neoplasms[25,26]. Moreover, meta-epidemiologic analyses have demonstrated that effect sizes tend to be slightly larger in single-centre trials for continuous outcomes, though no significant differences were found for binary outcomes[27]. A single-centre Italian study also found a higher frequency of the IDH1 rs11554137 polymorphism in brain tumor patients compared to controls, with prevalence varying according to tumor grade[28]. These findings reflect the need for careful interpretation of IDH prevalence across study designs and settings.

Longitudinal studies further demonstrate evolving trends in disease incidence and highlight the impact of diagnostic criteria on reported prevalence. For example, the incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in the Netherlands increased from 17.90 to 40.36 per 100000 between 1991 and 2010, likely reflecting improved diagnostic capabilities[29]. A similar trend is observed in idiopathic intracranial hypertension, which has shown rising incidence in parallel with increasing obesity rates[30]. However, in contrast to these conditions, IDH prevalence appears to be lower than previously assumed, with recent meta-analyses reporting rates < 12% when standardised definitions are applied[3]. This emphasizes the critical need for consistent diagnostic criteria in epidemiological research.

IDH prevalence also displays significant regional variation. Meta-analyses using standardised definitions report session-based prevalence rates of 10.1%-11.6%, yet individual studies reveal a wide range-from as low as 2.11% in Senegal to 17.2% in the United States[3,31,32]. Such disparities reflect not only differences in definitions and clinical practices but also facility-specific factors influencing IDH frequency[32]. Notably, the European Best Practice Guideline-which incorporates clinical symptoms and nursing interventions-tends to yield lower prevalence estimates compared to BP-only definitions[33]. Nevertheless, even lower prevalence does not negate IDH's clinical impact, as it remains associated with increased hospitalisation and mortality, reaffirming the need for rigorous prevention and management protocols[32].

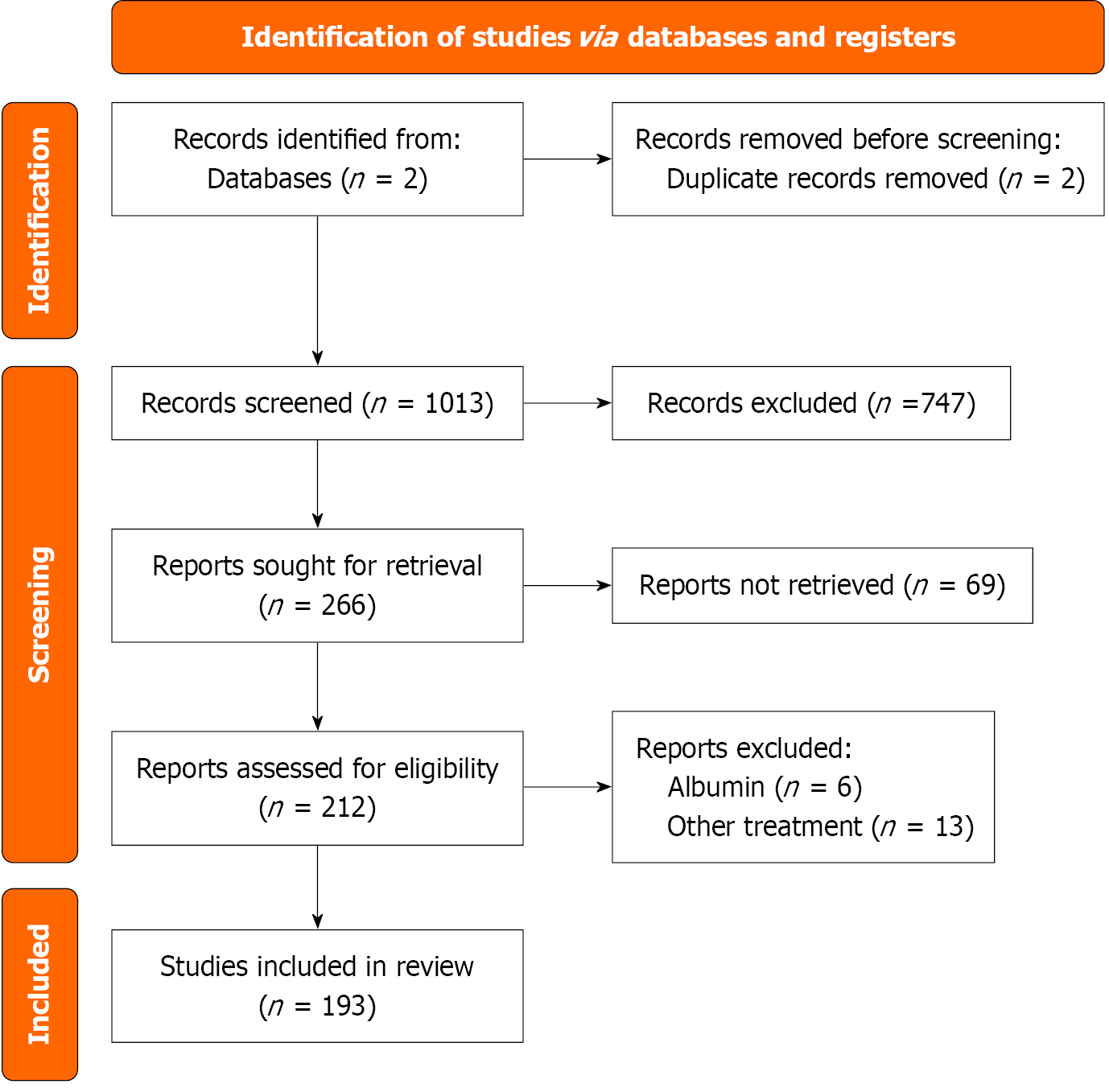

We conducted a comprehensive literature search in PubMed and Web of Science databases without any restrictions on time or geographical scope.

To ensure comprehensive coverage of the clinical and technological aspects of IDH, we used an expanded search strategy that included key terms related to HD, management, prevention, ultrafiltration, midodrine, biofeedback, and artificial intelligence (AI). This refinement allowed us to capture relevant studies addressing both conventional and emerging approaches to IDH assessment and treatment.

Our review adhered to the 2020 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. We excluded articles related to paediatric or pregnancy-associated cases, as well as studies focused exclu

Titles and abstracts were independently screened by two reviewers. Full-text retrieval was attempted for all potentially eligible articles. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. Data extraction focused on population characteristics, study design, outcomes related to IDH (including interventions, monitoring, and prediction), and methodological quality.

A PRISMA-style flow diagram summarizing the study selection process is presented in Figure 1.

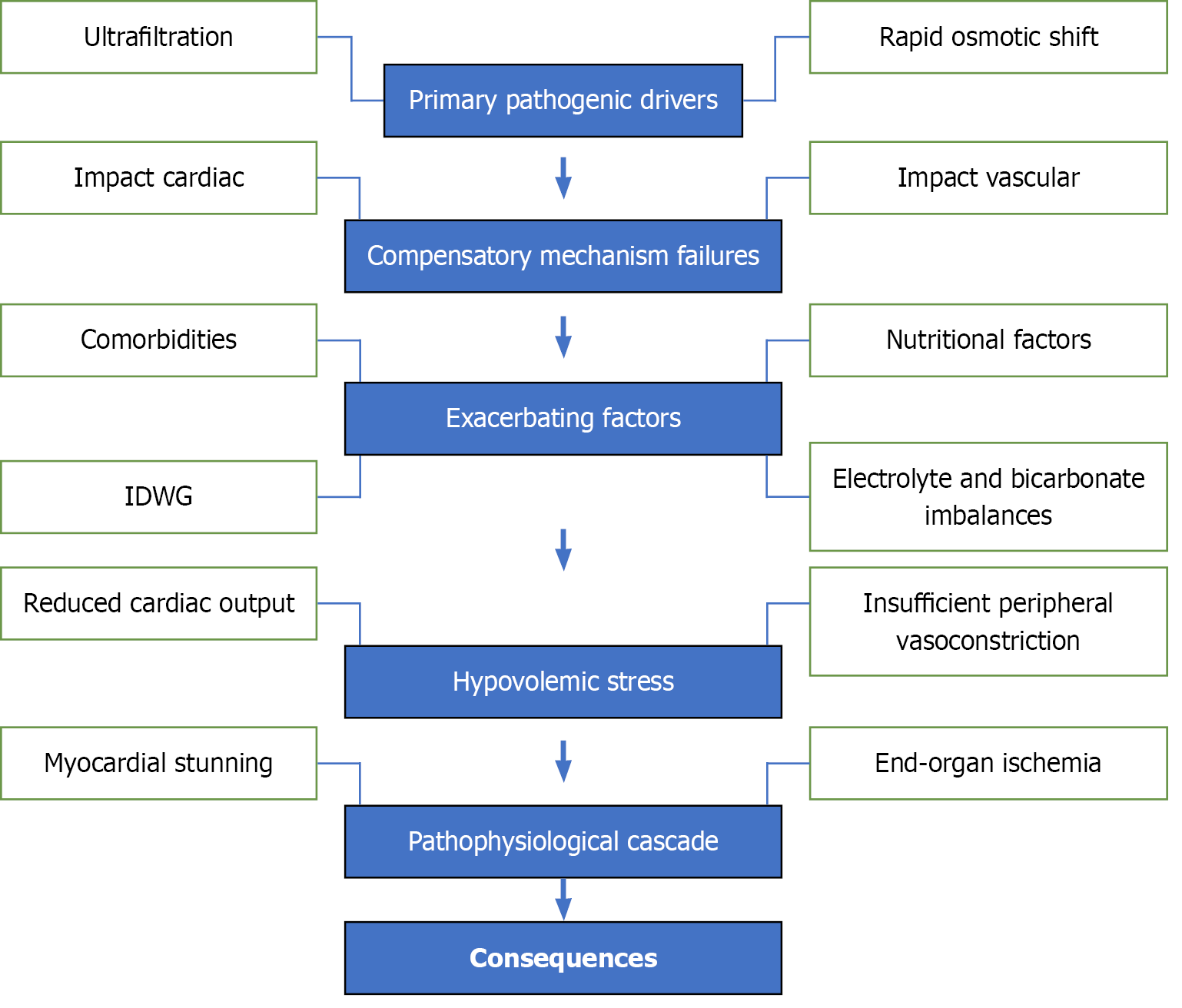

The development of IDH follows a multi-stage process (Figure 2), characterised by primary drivers, compensatory failures, exacerbating factors, hypovolemic stress, and a final pathophysiological cascade.

Ultrafiltration: During HD, fluid removal is achieved through ultrafiltration[10]. Excessively high UF rates (> 10-13 mL/kg/hour) overwhelm the body’s capacity for plasma volume refill, leading to a reduction in effective circulating blood volume. This hypovolemic state is a primary contributor to IDH[34].

Rapid osmotic shifts: HD facilitates the clearance of urea and other solutes, causing rapid changes in plasma osmolality. These shifts create transient osmotic gradients, driving fluid from the intravascular compartment into the intracellular and interstitial spaces. This further reduces the circulating blood volume and contributes to IDH[35].

Impaired cardiac output: Cardiac output (CO) depends on preload, afterload, heart rate, and myocardial contractility. In patients with comorbid conditions such as HF, these compensatory mechanisms may fail to adequately respond to the reduced blood volume, resulting in further reductions in CO[35].

Impaired vascular resistance: Autonomic dysfunction, prevalent in patients with CKD, impairs the ability to maintain vascular tone. This dysfunction reduces the compensatory vasoconstriction needed to counteract hypovolemia and maintain BP[36,37].

Comorbidities: Conditions such as diabetes mellitus, CVD, and autonomic neuropathy heighten the risk of IDH. These comorbidities impair the body’s ability to regulate vascular resistance and CO[38].

High IDWG: Excessive fluid retention between dialysis sessions necessitates aggressive UF rates, which further amplify the risk of IDH[39].

Nutritional factors: Food ingestion during dialysis redirects blood flow to the splanchnic region, reducing central circulatory volume. This effect is particularly significant in patients with autonomic dysfunction[36].

Electrolyte and bicarbonate imbalances: Overcorrection of metabolic acidosis or low dialysate calcium levels can compromise myocardial contractility, exacerbating hypotension[36].

The combined effects of reduced circulating blood volume and impaired compensatory mechanisms result in hypovo

Reduced CO: The heart cannot pump sufficient blood to maintain organ perfusion[35].

Insufficient peripheral vasoconstriction: Failing vascular tone prevents adequate redistribution of blood to vital organs[36,37].

Myocardial stunning: Hypoperfusion during IDH episodes induces transient myocardial ischemia, leading to reversible contractile dysfunction. Repeated episodes may progress to permanent cardiac damage[35].

End-organ ischemia: Reduced perfusion affects critical organs, including the brain, kidneys, and gastrointestinal tract. This can result in cerebral ischemia, accelerated loss of residual renal function, and mesenteric ischemia[35].

IDH risk factors can be categorised into patient-related, dialysis-related, pathophysiological, and modifiable factors (Table 1)[39,40]. These include comorbidities like diabetes, high UFR, electrolyte imbalances, autonomic dysfunction, and dietary habits.

| Risk factors | IDH risk profile |

| Patient-related risk factors | Comorbidities: Diabetes mellitus; cardiovascular diseases (heart failure, ischemic heart disease, diastolic dysfunction, arrhythmias); autonomic dysfunction, often linked to diabetes or advanced kidney disease; vascular calcification leading to arterial stiffness |

| Demographics: Age > 65 years; female sex; high body mass index or sarcopenia | |

| Nutritional and metabolic factors: Poor nutritional status (e.g., hypoalbuminemia); severe anemia; high IDWG, requiring higher UFR; electrolyte disturbances, particularly rapid bicarbonate influx and calcium shifts | |

| Dialysis-related risk factors | Dialysis prescription: High UFR (> 10-13 mL/kg/hour); short treatment time with rapid fluid removal; use of dialysate with high temperature or inappropriate sodium concentrations |

| Hemodynamic challenges: Failure of compensatory mechanisms, including impaired vascular tone and cardiac output; inadequate plasma refill rate during ultrafiltration | |

| Procedural issues: Food intake during dialysis sessions leading to splanchnic blood flow shifts | |

| Pathophysiological factors | Cardiac dysfunction: Reduced cardiac contractility or preload dependency during dialysis; recurrent myocardial stunning from repeated IDH episodes |

| Neurohumoral dysregulation: Blunted sympathetic nervous system response; loss of autonomic regulation, especially in diabetes | |

| Osmotic and fluid dynamics: Rapid shifts in serum osmolality due to urea clearance; poor vascular refill rates from interstitial to intravascular compartments | |

| Modifiable risk factors | IDWG: Control fluid and sodium intake to limit IDWG |

| Dialysis adjustments: Adjusting UFR, temperature, and sodium concentrations |

IDH has wide-ranging and significant consequences that affect patients both acutely and over the long term. Immedia

Cardiovascular complications are the most severe consequences of IDH. Recurrent episodes lead to myocardial stunning a condition caused by repetitive ischemic events that progressively weakens cardiac function and predisposes patients to HF[43]. This is further compounded by an increased risk of myocardial infarction and arrhythmias. Over time, the repeated cardiovascular strain contributes significantly to heightened mortality rates, especially from heart-related events[44].

Neurologically, IDH is associated with cerebral hypoperfusion, which can result in both transient and permanent brain injury[45]. This contributes to cognitive decline, increased risks of dementia, and visible structural brain changes, such as white matter injury and frontal atrophy. Cognitive impairment, including memory issues and slower processing speeds, becomes more prevalent among patients who frequently experience IDH episodes[46,47].

Renal health also deteriorates as IDH accelerates the loss of residual renal function[41]. Since residual renal function plays a critical role in fluid regulation and toxin clearance, its decline further exacerbates patient outcomes, increasing the risk of complications and mortality[11].

Other organ systems are similarly affected. IDH can lead to mesenteric ischemia, a serious condition resulting from compromised blood flow to the intestines[48]. While less common, liver ischemia has also been reported. Vascular health is another area of concern, as repeated hypotensive episodes can increase the risk of vascular access thrombosis and exacerbate arterial stiffness through calcification, reducing overall circulatory resilience[49,50].

Over the long term, IDH is a predictor of heightened mortality and poor overall survival, largely due to the cumulative effects of repeated organ ischemia[43]. By contributing to both acute discomfort and chronic health decline, IDH represents a critical challenge in the management of HD patients.

IDH remains a prevalent and clinically significant complication of HD, affecting 20%-30% of sessions and associated with increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality[51,52]. Among the primary contributing factors is an elevated ultrafiltration rate. Recommendations advise maintaining UFR < 12 mL/kg/hour, as exceeding 16 mL/kg/hour significantly raises the risk of IDH[53]. Extending dialysis duration to allow safer fluid removal has also been suggested to enhance haemodynamic stability[54]. However, the use of biofeedback mechanisms based on blood volume moni

Efforts to optimise haemodynamic tolerance have also included modifying dialysate temperature. Cooling dialysate to 35 °C has been shown to improve post-dialysis SBP, symptom burden, and solute clearance compared to standard 37 °C dialysate[57]. Additionally, dialysate at 34.5 °C can achieve vascular stability comparable to isolated ultrafiltration[58]. Combining mild hypothermia with progressive sodium reduction (from 150 mmol/L to 138 mmol/L) can further limit BP variability and IDH risk[59]. These effects may be enhanced through real-time blood temperature monitoring and automated dialysate temperature adjustment, or simply by routinely employing dialysate temperatures < 37 °C[60].

Beyond temperature control, sodium and ultrafiltration profiling have been explored as preventive strategies. While some evidence supports their efficacy in reducing IDH without increasing interdialytic weight gain, other studies have yielded inconsistent results[61,62]. Additional non-pharmacological interventions-such as dialysate cooling, extended dialysis sessions, and biofeedback technologies-also show potential. The association between elevated interdialytic weight gain (IDWG ≥ 3 kg) and IDH risk further underscores the importance of fluid management[63]. Given the heterogeneity of findings and the lack of consensus on a standardised definition of IDH, further investigation is essential to refine its prevention and treatment[64].

Pharmacologic interventions such as midodrine, an oral alpha-1 agonist, have been shown to elevate intra-dialysis and post-dialysis BP, reduce intravenous fluid requirements, and improve clinical symptoms when administered before dialysis[65-67]. These benefits have been maintained over time without significant adverse effects[65]. Nonetheless, more recent evaluations question the robustness of evidence supporting pharmacological therapies for IDH, including mido

The complexity of IDH extends to the management of antihypertensive medications, particularly around dialysis sessions. Though withholding antihypertensive agents before treatment is frequently recommended, the evidence supporting this practice is limited[68]. Recent findings reveal that the use of beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting-enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, and diuretics is associated with a higher risk of IDH compared to calcium channel blockers[69]. Adjustments in dialysis prescription-including modifying ultrafiltration targets, dialysate composition, and temperature-are complementary strategies, though no single pharmacologic measure has demonstrated consistent benefit in mitigating IDH[51,70].

In parallel, patient education plays a pivotal role in minimising IDWG and reducing IDH risk. Educational inter

Bioimpedance spectroscopy (BIS) has emerged as a promising tool for fluid management in high-risk patients. Its application has been linked to improved cardiovascular parameters, reduced fluid overload, and better BP control[75-77]. However, some studies have found no significant impact on mortality or cardiovascular events, suggesting that while BIS offers valuable data, its role in clinical decision-making requires further clarification[78].

Postural interventions such as the Trendelenburg position have traditionally been employed to counteract IDH, though their efficacy remains debated. While some evidence suggests transient improvements in stroke volume and MAP, other studies highlight potential risks and a lack of sustained benefits[79,80]. Despite limited evidence, widespread clinical use persists, often driven by tradition rather than empirical validation[81]. More robust data are needed to guide its appro

Emerging techniques for IDH prevention include bilateral lower limb sequential compression devices, which have shown promise in enhancing ultrafiltration goals[82]. Other interventions, such as cool dialysate to induce vasoconstriction, ultrafiltration profiling to optimize fluid removal timing, and biofeedback systems to regulate conductivity and ultrafiltration, may help preserve cardiovascular function and reduce hypotensive episodes. Increasing treatment frequency and duration, combined with sodium restriction in both dialysate and diet, further supports hemodynamic stability[83].

The development of advanced monitoring technologies offers new avenues for preventing IDH, especially in vulnerable populations. Continuous blood volume and temperature monitoring has been proposed to anticipate and mitigate hypotensive events, and wearable devices have shown early detection capabilities in at-risk individuals[84,85]. Digital advancements in hypertension management may offer further insights into remote monitoring and personalised interventions for BP regulation during dialysis. This is because the principles and technologies used to manage chronic hypertension outside of dialysis could potentially be adapted to monitor and predict acute drops in BP that characterise IDH[86]. Ongoing clinical trials are investigating the impact of healthcare provider education and patient activation strategies on IDH prevention and related outcomes[87].

BP variability has also emerged as a reliable predictor of IDH and mortality. Greater fluctuations in systolic pressure during and between dialysis sessions are independently associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes[88]. Lower pre-dialysis SBP and larger delta SBP have been identified as risk markers, while predictive models based on time-dependent logistic regression show high accuracy in forecasting IDH at upcoming BP checks[89,90]. These models may support timely and personalised interventions.

Finally, multidisciplinary care models contribute significantly to improving outcomes in both CKD and dialysis populations. Compared to standard care, these models have been shown to delay CKD progression, reduce mortality, and lower hospitalisation rates[91,92]. Integrated team-based approaches-featuring patient education, shared decision-making, and the use of telemedicine-enhance access to nephrology expertise, especially in underserved settings[92]. Nurse-led follow-ups further strengthen treatment adherence and contribute to reductions in IDH incidence, especially when multiple strategies are employed simultaneously. As demographic factors alone do not reliably predict non-compliance, personalised care remains essential[93-95]. Ongoing research seeks to compare the efficacy of provider-directed and patient-directed interventions to optimize symptom management, quality of life, and survival in this high-risk population[87].

IDH affects over 20% of HD sessions and is associated with heightened cardiovascular morbidity and mortality[52,64,95]. Despite this prevalence, its management is impeded by the absence of a universally accepted definition, as current diagnostic criteria vary considerably and frequently depend on inconsistently reported symptoms[4,64,96-98]. Among these, nadir-based thresholds-particularly SBP < 90 mmHg-demonstrate the strongest association with adverse outcomes such as mortality[8]. To enhance diagnostic accuracy, combining objective measures with clinical tools like the Patient-Reported IntraDialytic Symptom Score (PRISS) may provide a more robust framework[11].

To address this, we propose a practical, tiered clinical risk stratification framework that complements existing diagnostic tools and enables early identification of patients at elevated risk for IDH. This model classifies patients into low, moderate, or high-risk tiers based on key clinical factors, including diabetes mellitus, autonomic dysfunction (e.g., impaired heart rate variability), high interdialytic weight gain (IDWG > 3 kg), and hypoalbuminemia (< 3.5 g/dL)-all of which are independently associated with impaired vascular tone, reduced plasma refill, and increased hemodynamic instability[11,35,40]. High-risk individuals may benefit from targeted interventions such as dialysate cooling, ultrafil

While IDH is more commonly studied in adults, it also presents significant challenges in paediatric HD patients. Children often have lower blood volume reserves and greater cardiovascular variability, increasing their susceptibility to IDH[97]. Furthermore, the absence of paediatric-specific diagnostic thresholds and limited validation of adult-based interventions complicate management[98]. Factors such as growth requirements, nutritional status, and dialysis tolerance must be carefully balanced. Tailored strategies-including slower UFR, closer BP monitoring, and the use of paediatric-adapted dialysate prescriptions-are essential but underexplored[100]. More research is needed to define appropriate diagnostic criteria and preventive strategies for this vulnerable population.

To further enhance precision, this stratification model can be expanded through integration of AI and biomarker-based tools. Machine learning (ML) algorithms trained on dialysis session data-such as prior BP trends, ultrafiltration volumes, and nadir SBP-have demonstrated strong predictive performance, with most models achieving areas under the receiver-operating-characteristics curve (AUROC) values between 0.80 and 0.90, indicating good to excellent discrimination. While some studies report outlier values as high as 0.969, such findings may reflect overfitting or limited external validation and should be interpreted cautiously in the absence of real-world deployment evidence[90,101]. In these tools can be em

Technological innovations have emerged to mitigate IDH. BVM and individualised dialysate strategies aim to decrease the frequency of episodes[5,55,56], although current evidence remains inconclusive[63,84,102]. Simultaneously, biomar

Notably, progress in other fields, such as neuro-oncology, illustrates the broader potential of this approach. For example, AI-driven classification models[117] based on IDH mutations in gliomas have achieved diagnostic accuracies exceeding 90%, demonstrating the translational relevance of combining molecular diagnostics with ML[118-122]. Together, these advances underscore the importance of harmonising diagnostic definitions, integrating AI and biomarker tools, and embedding individualised risk models into clinical workflows to improve IDH outcomes.

Preventing IDH is essential for improving outcomes in HD patients and demands a multifaceted strategy, including optimisation of dialysis prescriptions, individualisation of treatment, and identification of patient-specific risk factors[95]. Core interventions involve the use of cool dialysate (35-36 °C), which induces vasoconstriction and stabilizes BP, alongside regulation of UFR, as excessive UFRs (> 10-13 mL/kg/hour) increase IDH risk[96-98]. Complementary mea

Further strategies include maintaining hydration and nutritional status, avoiding intradialytic food intake, and employing pharmacologic agents such as midodrine to enhance vascular tone[92,123,124]. Agents like L-carnitine and mannitol are under investigation for their potential benefit[51]. Adjusting antihypertensive therapies is also critical, as some classes may blunt compensatory cardiovascular responses[99]. Accurate fluid and electrolyte balance is vital, with tools like BIS and lung ultrasound (LUS) improving dry weight assessment[103-105]. Dialysate composition-particularly sodium and calcium concentrations-must be personalised, although the utility of sodium profiling remains debated due to associated side effects[106-108].

Emerging AI technologies offer real-time IDH risk prediction based on dialysis machine data, enabling proactive adjustments[109]. Adhering to best practices in the application of AI in healthcare is essential to ensure the reliable and ethical use of these predictive tools for IDH prevention[102]. In parallel, comprehensive patient education and interdisciplinary collaboration strengthen adherence and support tailored care[110]. These integrated efforts-spanning clinical practices, lifestyle changes, technological tools, and team-based approaches-can substantially mitigate the burden of IDH and enhance both survival and quality of life.

Midodrine, an oral α-1 adrenergic agonist, improves venous and arterial tone by increasing vascular resistance and venous return, thus supporting intradialytic BP[111-113]. Its favorable hemodynamic effects, particularly in patients with severe hypotension or HF, have established it as a cornerstone pharmacologic agent for IDH[111-114]. Studies have shown that midodrine enhances post-dialysis BP and tolerance to fluid removal with minimal adverse effects[65,99,123,124]. Doses typically range from 2.5 mg to 10 mg pre-dialysis, though administration up to 90 mg has been safely reported, notwithstanding rare complications like vascular ischemia[103,104].

Despite promising short-term outcomes, concerns persist regarding midodrine’s long-term efficacy and safety due to limited high-quality evidence[51]. Alternative agents-such as fludrocortisone, droxidopa, vasopressin, carnitine, and sertraline-are under investigation but currently lack robust comparative data and demonstrate modest effectiveness[51,105,106]. Pharmacological strategies must be contextualised within broader clinical parameters, including UFR, dialysate composition, and antihypertensive selection, as beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors may exacerbate IDH risk compared to calcium channel blockers[70,107,108].

Adjunctive therapies such as L-carnitine and mannitol offer potential benefits via metabolic and osmotic mechanisms, although findings remain mixed[109]. Mechanical techniques like intermittent pneumatic compression may augment venous return, yet results are inconclusive[110,111].

Intradialytic exercise-whether aerobic or resistance-based-has demonstrated positive effects on BP regulation, muscle strength, and mental well-being. Innovations like virtual reality further enhance patient engagement[112,113]. Among non-pharmacologic measures, cool dialysate remains the most effective, with one meta-analysis indicating a sevenfold reduction in IDH events. When combined with sodium ramping or ultrafiltration profiling, its efficacy is further ampli

Multidisciplinary approaches integrating dry weight reassessment, nutritional counseling, and individualised dialysis prescriptions are proven to significantly reduce IDH episodes[114]. Additionally, psychological interventions, including cognitive behavioral therapy and acupressure, help manage symptoms like insomnia and improve treatment adherence[115,116].

Technological advances are revolutionising IDH prevention. Biofeedback systems, such as Hemocontrol, automatically adjust ultrafiltration and dialysate conductivity, thereby enhancing cardiovascular stability, although outcomes remain heterogeneous[117]. Despite clinical rationale and favorable hemodynamic mechanisms, the evidence for both midodrine and biofeedback systems such as Hemocontrol remains inconclusive. Many trials suffer from small sample sizes, short durations, or single-center designs, limiting their statistical power and generalisability. Moreover, population heterogeneity-especially differences in baseline cardiovascular risk or autonomic function-may influence intervention effectiveness across cohorts. Studies also vary in their definitions of IDH and clinical endpoints, with some focusing on symptomatic relief while others assess surrogate markers like BP change or fluid removal tolerance. In midodrine studies, lack of placebo control and potential bias from unblinded designs further complicate interpretation. These methodological issues underscore the need for larger, rigorously designed trials with standardised endpoints to accurately assess the long-term efficacy and safety of these interventions.

Monitoring tools like BIS and LUS provide precise fluid status evaluation, aiding in the detection of subclinical fluid overload and refinement of dry weight targets[118,119].

AI-driven models utilising pre-dialysis data have demonstrated high accuracy (AUROC: 0.74-0.89) in predicting IDH, enabling timely and personalised interventions[90,120]. The integration of wearable hemodynamic monitors and digital platforms will likely transform IDH management, ensuring safer, patient-centered dialysis care[85,121]. While midodrine remains a pivotal agent, its role will increasingly be part of a broader, multidisciplinary, and technologically enhanced therapeutic paradigm.

Emerging technologies such as BIS and LUS are transforming fluid status assessment and target weight estimation in dialysis patients. BIS offers objective quantification of body fluid compartments, helping clinicians detect fluid overload and refine dry weight determinations[122]. Studies have shown that BIS-guided management improves BP control and reduces adverse events, although evidence on long-term outcomes such as mortality and hospitalisation remains mixed[125,126]. LUS complements BIS by offering real-time, non-invasive evaluation of extravascular lung water and venous congestion[127]. LUS demonstrates strong correlation with high-resolution computed tomography findings and ultrafil

Integration of BIS and LUS into routine clinical practice can improve patient outcomes by enhancing interdialytic BP control and reducing dialysis-related complications[131,132]. Despite these benefits, barriers remain, particularly for LUS, including lack of formal training, limited device availability, and time constraints[133-135]. However, standardised protocols and training programs have demonstrated success in increasing adoption and improving diagnostic accuracy across diverse settings[136]. The successful integration of BIS and LUS may depend on improving access, clinician education, and ongoing research to validate their long-term effectiveness in dialysis care.

In parallel with advances in fluid status monitoring, biofeedback-based technologies have evolved significantly to improve hemodynamic stability during dialysis. Closed-loop ultrafiltration systems that adjust treatment parameters in real time have been effective in reducing IDH[137]. BP-guided ultrafiltration and saline infusion using fuzzy logic show additional promise in stabilizing hemodynamics, while adaptive systems targeting dialysate conductivity and tempera

Although Hemocontrol and similar systems have shown encouraging results-particularly in patients prone to hypotension-clinical outcomes vary across studies, and limitations such as small sample sizes and inconsistent methodologies affect generalisability[83,137]. Additionally, individual response may differ: While some studies highlight im

Biofeedback technologies rely on precise and adaptive control of non-linear physiological processes. Advanced systems monitor blood volume, temperature, and pressure, adjusting dialysis parameters accordingly to prevent complications like IDH and myocardial stunning[83,146]. Yet, widespread adoption remains limited due to technical complexity and insufficient clinical validation. Of 28 studies identified by Dong et al[137], only 23 showed a significant benefit, empha

AI and ML are increasingly being incorporated into dialysis care, offering a new frontier in treatment personalisation. These technologies can analyze vast datasets-including patient history, biometric monitoring, and sensor data-to improve decision-making and refine biofeedback algorithms[147,148]. AI/ML applications have demonstrated high accuracy in predicting dialysis-related complications, including anaemia, IDH, and fluid shifts[149]. For example, ML models using features like SBP, previous IDH episodes, and nadir BP values have achieved AUROC values up to 0.969 for IDH prediction[101,150].

Beyond IDH, AI has also shown utility in predicting acute kidney injury, optimising anaemia management, and enhancing patient engagement through digital twins and large language models[151-153]. Integration of real-time monitoring systems with AI could enable dynamic adjustment of dialysis prescriptions based on individual responses[149]. Wearable technologies and non-contact sensors further enhance AI capabilities by providing continuous data streams, allowing for early detection of cardiovascular deterioration and hemodynamic instability[154,155].

Despite these advancements, significant challenges remain in AI/ML implementation, including the need for trans

AI-based decision support systems (AI-DSS) show particular promise in anaemia management and insulin dosing, with some models demonstrating outcomes comparable to expert clinicians[152,160]. In HD, AI-DSS can reduce hemoglo

Combining predictive analytics, real-time monitoring, and biofeedback technologies may lead to a more adaptive and responsive form of dialysis-one that shifts from reactive to proactive care. As ML models improve, they will enable earlier identification of high-risk patients and facilitate timely interventions to reduce IDH and other complications[90,120]. Continued research into AI explainability, real-world validation, and clinical integration will be critical to realize the full potential of these tools and to establish more physiologic, intelligent dialysis systems[148,162].

Despite the emergence of promising strategies and technological tools for the prevention and management of IDH, several practical barriers limit their widespread implementation across dialysis centres. One key challenge is staff training and expertise. Interventions such as LUS and BIS require specific technical skills and interpretative knowledge, which may be lacking in facilities with limited access to nephrology specialists or ongoing professional development programs[69]. Training constraints can lead to inconsistent use or misinterpretation of results, thereby undermining their effectiveness.

Cost and resource limitations also pose significant obstacles. Advanced tools like AI-driven predictive platforms, wearable hemodynamic monitors, and integrated biofeedback systems may involve substantial initial investment, ongoing maintenance, and information technology infrastructure. These financial constraints are particularly relevant in low-resource settings, where dialysis centres often operate with limited budgets and prioritize essential over innovative care[163]. Addressing the social responsibility of kidney healthcare facilities in Africa highlights practical pathways to improve equity, accountability, and sustainability in dialysis delivery in such settings[164].

Equipment availability and accessibility vary significantly across regions and institutions. While some centres may have immediate access to devices like BIS or real-time blood volume monitors, others struggle with procurement, calibration, or maintenance issues. This disparity contributes to inter-facility variation in practice standards and may widen healthcare inequities.

Finally, workflow integration and clinical inertia can hinder adoption. Introducing new tools or protocols requires restructuring care delivery, retraining staff, and integrating systems with electronic health records-all of which demand time and institutional commitment. Without clear incentives or demonstrated cost-effectiveness, implementation may lag despite supportive evidence.

Collectively, these barriers highlight the importance of health system-level planning, targeted funding, and workforce development to ensure equitable and effective uptake of IDH innovations.

Existing gaps in the management of IDH are profound and span both nephrology and neuro-oncology, stemming from a lack of consensus definitions and limited longitudinal data on interventions. In HD, IDH is prevalent and linked to significant cardiovascular and systemic complications, yet preventive strategies and pharmacologic treatments lack robust, long-term evaluation[5,51,107]. Similarly, in IDH-mutant gliomas, although targeted inhibitors like vorasidenib show potential, optimal treatment strategies remain unclear, partly due to variability in mutation detection methods and evolving classification systems[165-167]. In both fields, the absence of standardised criteria hinders outcome assessment and comparability[4,168]. Efforts to harmonize guidelines through initiatives like GRADE in nephrology and molecu

IDH remains a persistent and clinically significant complication in the management of HD, with profound implications for cardiovascular stability, cerebral integrity, and patient survival. This comprehensive review has elucidated the multifactorial pathophysiology of IDH-driven by hypovolaemia, autonomic dysfunction, and inadequate compensatory mechanisms-while also detailing its acute and chronic consequences, including myocardial stunning, cognitive decline, and protein-energy wasting.

A key barrier to progress is the heterogeneity in IDH definitions, which hinders study comparability, obscures accurate prevalence estimates, and delays the implementation of evidence-based practices. To address this, the synthesis of current evidence underscores the need for tailored management strategies that integrate pharmacological, non-pharmacological, and technological approaches.

Preventive interventions such as individualised fluid removal, dialysate cooling, sodium and ultrafiltration profiling, and nutritional optimisation, combined with therapeutic options including midodrine and intradialytic exercise, offer promising avenues to mitigate IDH. Additionally, multidisciplinary care models have demonstrated efficacy in managing the complex interplay of risk factors.

Advances in AI and ML are transforming IDH prediction and prevention through real-time analytics, dynamic risk stratification, and personalised treatment algorithms. Technologies such as BIS and LUS further enhance volume status assessment and support precision-targeted care.

Despite these innovations, notable challenges remain. There is an urgent need for consensus-based definitions, standardised diagnostic thresholds, and longitudinal clinical trials to evaluate the long-term efficacy and safety of current interventions. Future research should prioritise validation of predictive biomarkers, integration of omics data, and utilisation of real-world evidence to inform precision medicine approaches.

Ultimately, addressing the multidimensional nature of IDH requires a paradigm shift towards integrated, patient-centred, and data-driven care. Through interdisciplinary collaboration, technological advancement, and sustained innovation, we can reduce the burden of IDH and improve the quality of life for patients reliant on HD.

| 1. | Saran R, Robinson B, Abbott KC, Agodoa LYC, Bragg-Gresham J, Balkrishnan R, Bhave N, Dietrich X, Ding Z, Eggers PW, Gaipov A, Gillen D, Gipson D, Gu H, Guro P, Haggerty D, Han Y, He K, Herman W, Heung M, Hirth RA, Hsiung JT, Hutton D, Inoue A, Jacobsen SJ, Jin Y, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kapke A, Kleine CE, Kovesdy CP, Krueter W, Kurtz V, Li Y, Liu S, Marroquin MV, McCullough K, Molnar MZ, Modi Z, Montez-Rath M, Moradi H, Morgenstern H, Mukhopadhyay P, Nallamothu B, Nguyen DV, Norris KC, O'Hare AM, Obi Y, Park C, Pearson J, Pisoni R, Potukuchi PK, Repeck K, Rhee CM, Schaubel DE, Schrager J, Selewski DT, Shamraj R, Shaw SF, Shi JM, Shieu M, Sim JJ, Soohoo M, Steffick D, Streja E, Sumida K, Kurella Tamura M, Tilea A, Turf M, Wang D, Weng W, Woodside KJ, Wyncott A, Xiang J, Xin X, Yin M, You AS, Zhang X, Zhou H, Shahinian V. US Renal Data System 2018 Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;73:A7-A8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 486] [Cited by in RCA: 716] [Article Influence: 102.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Shoji T, Tsubakihara Y, Fujii M, Imai E. Hemodialysis-associated hypotension as an independent risk factor for two-year mortality in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2004;66:1212-1220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 409] [Cited by in RCA: 453] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kuipers J, Verboom LM, Ipema KJR, Paans W, Krijnen WP, Gaillard CAJM, Westerhuis R, Franssen CFM. The Prevalence of Intradialytic Hypotension in Patients on Conventional Hemodialysis: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Am J Nephrol. 2019;49:497-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Assimon MM, Flythe JE. Definitions of intradialytic hypotension. Semin Dial. 2017;30:464-472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gullapudi VRL, Kazmi I, Selby NM. Techniques to improve intradialytic haemodynamic stability. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2018;27:413-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | K/DOQI Workgroup. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for cardiovascular disease in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45:S1-153. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Hirakata H, Nitta K, Inaba M, Shoji T, Fujii H, Kobayashi S, Tabei K, Joki N, Hase H, Nishimura M, Ozaki S, Ikari Y, Kumada Y, Tsuruya K, Fujimoto S, Inoue T, Yokoi H, Hirata S, Shimamoto K, Kugiyama K, Akiba T, Iseki K, Tsubakihara Y, Tomo T, Akizawa T; Japanese Society for Dialysis Therapy. Japanese Society for Dialysis Therapy guidelines for management of cardiovascular diseases in patients on chronic hemodialysis. Ther Apher Dial. 2012;16:387-435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Flythe JE, Xue H, Lynch KE, Curhan GC, Brunelli SM. Association of mortality risk with various definitions of intradialytic hypotension. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:724-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 226] [Cited by in RCA: 347] [Article Influence: 28.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Arcentales-Vera K, Vera-Mendoza MF, Cevallos-Salas C, García-Aguilera MF, Fuenmayor-González L. Prevalence of cardiovascular instability during hemodialysis therapy in hospitalized patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Prog. 2024;107:368504241308982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Prabhu RA, Naik B, Bhojaraja MV, Rao IR, Shenoy SV, Nagaraju SP, Rangaswamy D. Intradialytic hypertension prevalence and predictive factors: A single centre study. J Nephropathol. 2021;11:e17206-e17206. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kuipers J, Oosterhuis JK, Paans W, Krijnen WP, Gaillard CAJM, Westerhuis R, Franssen CFM. Association between quality of life and various aspects of intradialytic hypotension including patient-reported intradialytic symptom score. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20:164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | MacGregor MS, Agar JW, Blagg CR. Home haemodialysis-international trends and variation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:1934-1945. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rocha A, Sousa C, Teles P, Coelho A, Xavier E. Frequency of intradialytic hypotensive episodes: old problem, new insights. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2015;9:763-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Park YW, Yun D, Yu Y, Kim SH, Park S, Kim YC, Kim DK, Oh KH, Joo KW, Kim YS, Kim SG, Han SS. Intradialytic hypotension and worse outcomes in patients with acute kidney injury requiring intermittent hemodialysis. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2024;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bossola M, Laudisio A, Antocicco M, Panocchia N, Tazza L, Colloca G, Tosato M, Zuccalà G. Intradialytic hypotension is associated with dialytic age in patients on chronic hemodialysis. Ren Fail. 2013;35:1260-1263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Davenport A. Why is Intradialytic Hypotension the Commonest Complication of Outpatient Dialysis Treatments? Kidney Int Rep. 2023;8:405-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Rocha A, Sousa C, Teles P, Coelho A, Xavier E. Effect of Dialysis Day on Intradialytic Hypotension Risk. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2016;41:168-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Correa S, Guerra-torres XE, Waikar SS, Mc Causland FR. Risk of intradialytic hypotension by day of the week in maintenance hemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35:gfaa139.SO087. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Keane DF, Raimann JG, Zhang H, Willetts J, Thijssen S, Kotanko P. The time of onset of intradialytic hypotension during a hemodialysis session associates with clinical parameters and mortality. Kidney Int. 2021;99:1408-1417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sohn P, Narasaki Y, Rhee CM. Intradialytic hypotension: is timing everything? Kidney Int. 2021;99:1269-1272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hours M, Siemiatycki J, Fabry J, Francois R. [Time clustering and temporospatial regrouping study of cases of juvenile diabetes in the district of Rhône (1960-1980)]. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 1990;38:287-295. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Kalita J, Misra UK. Disease Specific Seasonal Influence- Geography and Economy Maters. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2020;23:3-4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Venteicher AS, Tirosh I, Hebert C, Yizhak K, Neftel C, Filbin MG, Hovestadt V, Escalante LE, Shaw ML, Rodman C, Gillespie SM, Dionne D, Luo CC, Ravichandran H, Mylvaganam R, Mount C, Onozato ML, Nahed BV, Wakimoto H, Curry WT, Iafrate AJ, Rivera MN, Frosch MP, Golub TR, Brastianos PK, Getz G, Patel AP, Monje M, Cahill DP, Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Louis DN, Bernstein BE, Regev A, Suvà ML. Decoupling genetics, lineages, and microenvironment in IDH-mutant gliomas by single-cell RNA-seq. Science. 2017;355:eaai8478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 523] [Cited by in RCA: 725] [Article Influence: 80.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Paltiel O. Family matters in Hodgkin lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49:1234-1235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Al Abri Y, Al Huneini M, Al Zadjali S, Al Rawahi M. IDH1 and IDH2 Gene Mutations in Omani Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Prognostic Significance and Clinic-pathologic Features. Oman Med J. 2024;39:e592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Tefferi A, Lasho TL, Abdel-Wahab O, Guglielmelli P, Patel J, Caramazza D, Pieri L, Finke CM, Kilpivaara O, Wadleigh M, Mai M, McClure RF, Gilliland DG, Levine RL, Pardanani A, Vannucchi AM. IDH1 and IDH2 mutation studies in 1473 patients with chronic-, fibrotic- or blast-phase essential thrombocythemia, polycythemia vera or myelofibrosis. Leukemia. 2010;24:1302-1309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 272] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Alexander PE, Bonner AJ, Agarwal A, Li SA, Hariharan A 4th, Izhar Z, Bhatnagar N, Alba C, Akl EA, Fei Y, Guyatt GH, Beyene J. Sensitivity subgroup analysis based on single-center vs. multi-center trial status when interpreting meta-analyses pooled estimates: the logical way forward. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;74:80-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Acquaviva G, Visani M, de Biase D, Marucci G, Franceschi E, Tosoni A, Brandes AA, Rhoden KJ, Pession A, Tallini G. Prevalence of the single-nucleotide polymorphism rs11554137 (IDH1(105GGT)) in brain tumors of a cohort of Italian patients. Sci Rep. 2018;8:4459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | van den Heuvel TRA, Jeuring SFG, Zeegers MP, van Dongen DHE, Wolters A, Masclee AAM, Hameeteman WH, Romberg-Camps MJL, Oostenbrug LE, Pierik MJ, Jonkers DM. A 20-Year Temporal Change Analysis in Incidence, Presenting Phenotype and Mortality, in the Dutch IBDSL Cohort-Can Diagnostic Factors Explain the Increase in IBD Incidence? J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:1169-1179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | McCluskey G, Doherty-Allan R, McCarron P, Loftus AM, McCarron LV, Mulholland D, McVerry F, McCarron MO. Meta-analysis and systematic review of population-based epidemiological studies in idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Eur J Neurol. 2018;25:1218-1227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Mamadou BA, Kane Y, Faye M, Dieng A, Bacary B, Keita N, Ndiaye B, Ndongo M, Abou S, Faye M, Lemrabott AT, Fary KE. Intra-Dialytique Hypotension: Prevalence and Associated Factors in 2 Haemodialysis Centres in Senegal. Open J Nephrol. 2022;12:361-368. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 32. | Sands JJ, Usvyat LA, Sullivan T, Segal JH, Zabetakis P, Kotanko P, Maddux FW, Diaz-Buxo JA. Intradialytic hypotension: frequency, sources of variation and correlation with clinical outcome. Hemodial Int. 2014;18:415-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kuipers J, Oosterhuis JK, Krijnen WP, Dasselaar JJ, Gaillard CA, Westerhuis R, Franssen CF. Prevalence of intradialytic hypotension, clinical symptoms and nursing interventions--a three-months, prospective study of 3818 haemodialysis sessions. BMC Nephrol. 2016;17:21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Saran R, Bragg-Gresham JL, Levin NW, Twardowski ZJ, Wizemann V, Saito A, Kimata N, Gillespie BW, Combe C, Bommer J, Akiba T, Mapes DL, Young EW, Port FK. Longer treatment time and slower ultrafiltration in hemodialysis: associations with reduced mortality in the DOPPS. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1222-1228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 381] [Cited by in RCA: 384] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Daugirdas JT. Pathophysiology of dialysis hypotension: an update. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;38:S11-S17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 201] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Daul AE, Wang XL, Michel MC, Brodde OE. Arterial hypotension in chronic hemodialyzed patients. Kidney Int. 1987;32:728-735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | de los Reyes V AA, Fuertinger DH, Kappel F, Meyring-Wösten A, Thijssen S, Kotanko P. A physiologically based model of vascular refilling during ultrafiltration in hemodialysis. J Theor Biol. 2016;390:146-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Feng Y, Zou Y, Zheng Y, Levin NW, Wang L. The value of non-invasive measurement of cardiac output and total peripheral resistance to categorize significant changes of intradialytic blood pressure: a prospective study. BMC Nephrol. 2018;19:310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Singh AT, Mc Causland FR. Osmolality and blood pressure stability during hemodialysis. Semin Dial. 2017;30:509-517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Hamrahian SM, Vilayet S, Herberth J, Fülöp T. Prevention of Intradialytic Hypotension in Hemodialysis Patients: Current Challenges and Future Prospects. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2023;16:173-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Caplin B, Kumar S, Davenport A. Patients' perspective of haemodialysis-associated symptoms. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:2656-2663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Canty JM Jr, Fallavollita JA. Chronic hibernation and chronic stunning: a continuum. J Nucl Cardiol. 2000;7:509-527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Burton JO, Jefferies HJ, Selby NM, McIntyre CW. Hemodialysis-induced cardiac injury: determinants and associated outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:914-920. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 446] [Cited by in RCA: 540] [Article Influence: 31.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Owen PJ, Priestman WS, Sigrist MK, Lambie SH, John SG, Chesterton LJ, McIntyre CW. Myocardial contractile function and intradialytic hypotension. Hemodial Int. 2009;13:293-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | MacEwen C, Sutherland S, Daly J, Pugh C, Tarassenko L. Relationship between Hypotension and Cerebral Ischemia during Hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:2511-2520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Eldehni MT, Odudu A, McIntyre CW. Randomized clinical trial of dialysate cooling and effects on brain white matter. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:957-965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Assimon MM, Wang L, Flythe JE. Cumulative Exposure to Frequent Intradialytic Hypotension Associates With New-Onset Dementia Among Elderly Hemodialysis Patients. Kidney Int Rep. 2019;4:603-606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Ortiz A, Garron MP, Navarro A, Rodriguez-Barbero JM, Aguilera B, Caramelo C. Ischaemic hepatic necrosis and intestinal infarction in a haemodialysis patient. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1991;6:521-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Seong EY, Zheng Y, Winkelmayer WC, Montez-Rath ME, Chang TI. The Relationship between Intradialytic Hypotension and Hospitalized Mesenteric Ischemia: A Case-Control Study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13:1517-1525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Ori Y, Chagnac A, Schwartz A, Herman M, Weinstein T, Zevin D, Gafter U, Korzets A. Non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia in chronically dialyzed patients: a disease with multiple risk factors. Nephron Clin Pract. 2005;101:c87-c93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Chang TI. Impact of drugs on intradialytic hypotension: Antihypertensives and vasoconstrictors. Semin Dial. 2017;30:532-536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Stefánsson BV, Brunelli SM, Cabrera C, Rosenbaum D, Anum E, Ramakrishnan K, Jensen DE, Stålhammar NO. Intradialytic hypotension and risk of cardiovascular disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9:2124-2132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 240] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Thongdee C, Phinyo P, Patumanond J, Satirapoj B, Spilles N, Laonapaporn B, Tantiyavarong P, Tasanarong A. Ultrafiltration rates and intradialytic hypotension: A case-control sampling of pooled haemodialysis data. J Ren Care. 2021;47:34-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Aronoff GR. The effect of treatment time, dialysis frequency, and ultrafiltration rate on intradialytic hypotension. Semin Dial. 2017;30:489-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Leung KCW, Quinn RR, Ravani P, Duff H, MacRae JM. Randomized Crossover Trial of Blood Volume Monitoring-Guided Ultrafiltration Biofeedback to Reduce Intradialytic Hypotensive Episodes with Hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12:1831-1840. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Leung KC, Quinn RR, Ravani P, MacRae JM. Ultrafiltration biofeedback guided by blood volume monitoring to reduce intradialytic hypotensive episodes in hemodialysis: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15:483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Azar AT. Effect of dialysate temperature on hemodynamic stability among hemodialysis patients. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2009;20:596-603. [PubMed] |

| 58. | Maggiore O, Pizzarelli F, Zoccali C, Sisca S. hemodialysis and isolated. Int J Artif Organs. 1985;8:175-178. |

| 59. | Ebrahimi H, Safavi M, Saeidi MH, Emamian MH. Effects of Sodium Concentration and Dialysate Temperature Changes on Blood Pressure in Hemodialysis Patients: A Randomized, Triple-Blind Crossover Clinical Trial. Ther Apher Dial. 2017;21:117-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Pérgola PE, Habiba NM, Johnson JM. Body temperature regulation during hemodialysis in long-term patients: is it time to change dialysate temperature prescription? Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44:155-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 61. | Ghafourifard M, Rafieian M, Shahgholian N, Mortazavi M. Effect of sodium dialysate variation in combining with ultra filtration on intradialytic hypotension and intradialytic weight gain for patients on hemodialysis. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2009;19:19-26. |

| 62. | Hamzi AM, Asseraji M, Hassani K, Alayoud A, Abdellali B, Zajjari Y, Montacer DB, Akhmouch I, Benyahia M, Oualim Z. Applying sodium profile with or without ultrafiltration profile failed to show beneficial effects on the incidence of intradialytic hypotension in susceptible hemodilaysis patients. Arab J Nephrol Transplant. 2012;5:129-134. [PubMed] |

| 63. | Gul A, Miskulin D, Harford A, Zager P. Intradialytic hypotension. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2016;25:545-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Kanbay M, Ertuglu LA, Afsar B, Ozdogan E, Siriopol D, Covic A, Basile C, Ortiz A. An update review of intradialytic hypotension: concept, risk factors, clinical implications and management. Clin Kidney J. 2020;13:981-993. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 22.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Cruz DN, Mahnensmith RL, Brickel HM, Perazella MA. Midodrine is effective and safe therapy for intradialytic hypotension over 8 months of follow-up. Clin Nephrol. 1998;50:101-107. [PubMed] |

| 66. | Lim PS, Yang CC, Li HP, Lim YT, Yeh CH. Midodrine for the treatment of intradialytic hypotension. Nephron. 1997;77:279-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Flynn JJ 3rd, Mitchell MC, Caruso FS, McElligott MA. Midodrine treatment for patients with hemodialysis hypotension. Clin Nephrol. 1996;45:261-267. [PubMed] |

| 68. | Wang KM, Sirich TL, Chang TI. Timing of blood pressure medications and intradialytic hypotension. Semin Dial. 2019;32:201-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Zoccali C. Lung Ultrasound in the Management of Fluid Volume in Dialysis Patients: Potential Usefulness. Semin Dial. 2017;30:6-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Sherman RA. Modifying the dialysis prescription to reduce intradialytic hypotension. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;38:S18-S25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Sharaf AY. The impact of educational interventions on hemodialysis patients’ adherence to fluid and sodium restrictions. IOSR J Nurs Health Sci. 2016;5:50-60. |

| 72. | Nadri A, Khanoussi A, Hssaine Y, Chettati M, Fadili W, Laouad I. [Effect of a hemodialysis patient education on fluid control and dietary]. Nephrol Ther. 2020;16:353-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Bossola M, Pepe G, Antocicco M, Severino A, Di Stasio E. Interdialytic weight gain and educational/cognitive, counseling/behavioral and psychological/affective interventions in patients on chronic hemodialysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Nephrol. 2022;35:1973-1983. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Barnett T, Li Yoong T, Pinikahana J, Si-Yen T. Fluid compliance among patients having haemodialysis: can an educational programme make a difference? J Adv Nurs. 2008;61:300-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Onofriescu M, Hogas S, Voroneanu L, Apetrii M, Nistor I, Kanbay M, Covic AC. Bioimpedance-guided fluid management in maintenance hemodialysis: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64:111-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Moissl U, Arias-Guillén M, Wabel P, Fontseré N, Carrera M, Campistol JM, Maduell F. Bioimpedance-guided fluid management in hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8:1575-1582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Ebrahim MB, Elsharkawy MM, Elsaid HW, Hassan MS. Effect of Fluid Management Guided by Bioimpedance Spectroscopy on Cardiovascular Parameters inHigh Risk Hemodialysis Patients. QJM Int J Med. 2020;113. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 78. | Tabinor M, Davies SJ. The use of bioimpedance spectroscopy to guide fluid management in patients receiving dialysis. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2018;27:406-412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Likhvantsev VV, Landoni G, Berikashvili LB, Polyakov PA, Ya Yadgarov M, Ryzhkov PV, Plotnikov GP, Kornelyuk RA, Komkova VV, Zaraca L, Kuznetsov IV, Smirnova AV, Kadantseva KK, Shemetova MM. Hemodynamic Impact of the Trendelenburg Position: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2025;39:256-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Geer KD. Reconsidering the Trendelenburg position during intradialytic hypotension. Nursing. 2022;52:41-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Ostrow CL. Use of the Trendelenburg position by critical care nurses: Trendelenburg survey. Am J Crit Care. 1997;6:172-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Onuigbo MA. Bilateral lower extremity sequential compression devices (SCDs): a novel approach to the management of intra-dialytic hypotension in the outpatient setting--report of a case series. Ren Fail. 2010;32:32-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Agarwal R. How can we prevent intradialytic hypotension? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2012;21:593-599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Damasiewicz MJ, Polkinghorne KR. Intra-dialytic hypotension and blood volume and blood temperature monitoring. Nephrology (Carlton). 2011;16:13-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Kolben Y, Gork I, Peled D, Amitay S, Moshel P, Goldstein N, Ben Ishay A, Fons M, Tabi M, Eisenkraft A, Gepner Y, Nachman D. Continuous Monitoring of Advanced Hemodynamic Parameters during Hemodialysis Demonstrated Early Variations in Patients Experiencing Intradialytic Hypotension. Biomedicines. 2024;12:1177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Ramdani S, Benkaddour NEH, Haddiya I. Digital advancements in hypertension management. 2024 3rd International Conference on Embedded Systems and Artificial Intelligence (ESAI). Morocco: IEEE. 2024: 1-13. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 87. | Veinot TC, Gillespie B, Argentina M, Bragg-Gresham J, Chatoth D, Collins Damron K, Heung M, Krein S, Wingard R, Zheng K, Saran R. Enhancing the Cardiovascular Safety of Hemodialysis Care Using Multimodal Provider Education and Patient Activation Interventions: Protocol for a Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2023;12:e46187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Flythe JE, Inrig JK, Shafi T, Chang TI, Cape K, Dinesh K, Kunaparaju S, Brunelli SM. Association of intradialytic blood pressure variability with increased all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients treated with long-term hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61:966-974. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Sangala N, Gangaram V, Atkins K, Elliot G, Lewis R. Intra-dialytic hypotension: Identifying patients most at risk. J Ren Care. 2017;43:92-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Lin CJ, Chen CY, Wu PC, Pan CF, Shih HM, Huang MY, Chou LH, Tang JS, Wu CJ. Intelligent system to predict intradialytic hypotension in chronic hemodialysis. J Formos Med Assoc. 2018;117:888-893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Strand H, Parker D. Effectiveness of medical compared to multidisciplinary models of care for adult persons with pre-dialysis chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. JBI Libr Syst Rev. 2010;8:1058-1087. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Ramar P, Ahmed AT, Wang Z, Chawla SS, Suarez MLG, Hickson LJ, Farrell A, Williams AW, Shah ND, Murad MH, Thorsteinsdottir B. Effects of Different Models of Dialysis Care on Patient-Important Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Popul Health Manag. 2017;20:495-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Arad M, Goli R, Parizad N, Vahabzadeh D, Baghaei R. Do the patient education program and nurse-led telephone follow-up improve treatment adherence in hemodialysis patients? A randomized controlled trial. BMC Nephrol. 2021;22:119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Tai DJ, Conley J, Ravani P, Hemmelgarn BR, MacRae JM. Hemodialysis prescription education decreases intradialytic hypotension. J Nephrol. 2013;26:315-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Morgan L. A decade review: methods to improve adherence to the treatment among haemodialysis patients. EDTNA ERCA J. 2001;27:7-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Selby NM, McIntyre CW. A systematic review of the clinical effects of reducing dialysate fluid temperature. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:1883-1898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Raina R, Lam S, Raheja H, Krishnappa V, Hothi D, Davenport A, Chand D, Kapur G, Schaefer F, Sethi SK, McCulloch M, Bagga A, Bunchman T, Warady BA. Pediatric intradialytic hypotension: recommendations from the Pediatric Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy (PCRRT) Workgroup. Pediatr Nephrol. 2019;34:925-941. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Hayes W, Hothi DK. Intradialytic hypotension. Pediatr Nephrol. 2011;26:867-879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |