Published online Dec 25, 2025. doi: 10.5527/wjn.v14.i4.109382

Revised: June 17, 2025

Accepted: September 17, 2025

Published online: December 25, 2025

Processing time: 228 Days and 20.5 Hours

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) contributes significantly to emergency department (ED) presentations in low- and middle-income countries. These patients fre

To identify baseline predictors of in-hospital mortality in adult Indian patients with CKD admitted to the ED.

This retrospective study was conducted from January 2021 to December 2022 at the Acute Care and Emergency Medicine Unit of the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India. CKD was diagnosed and staged following the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes guidelines. Data were extracted from medical records using a structured form. All consecu

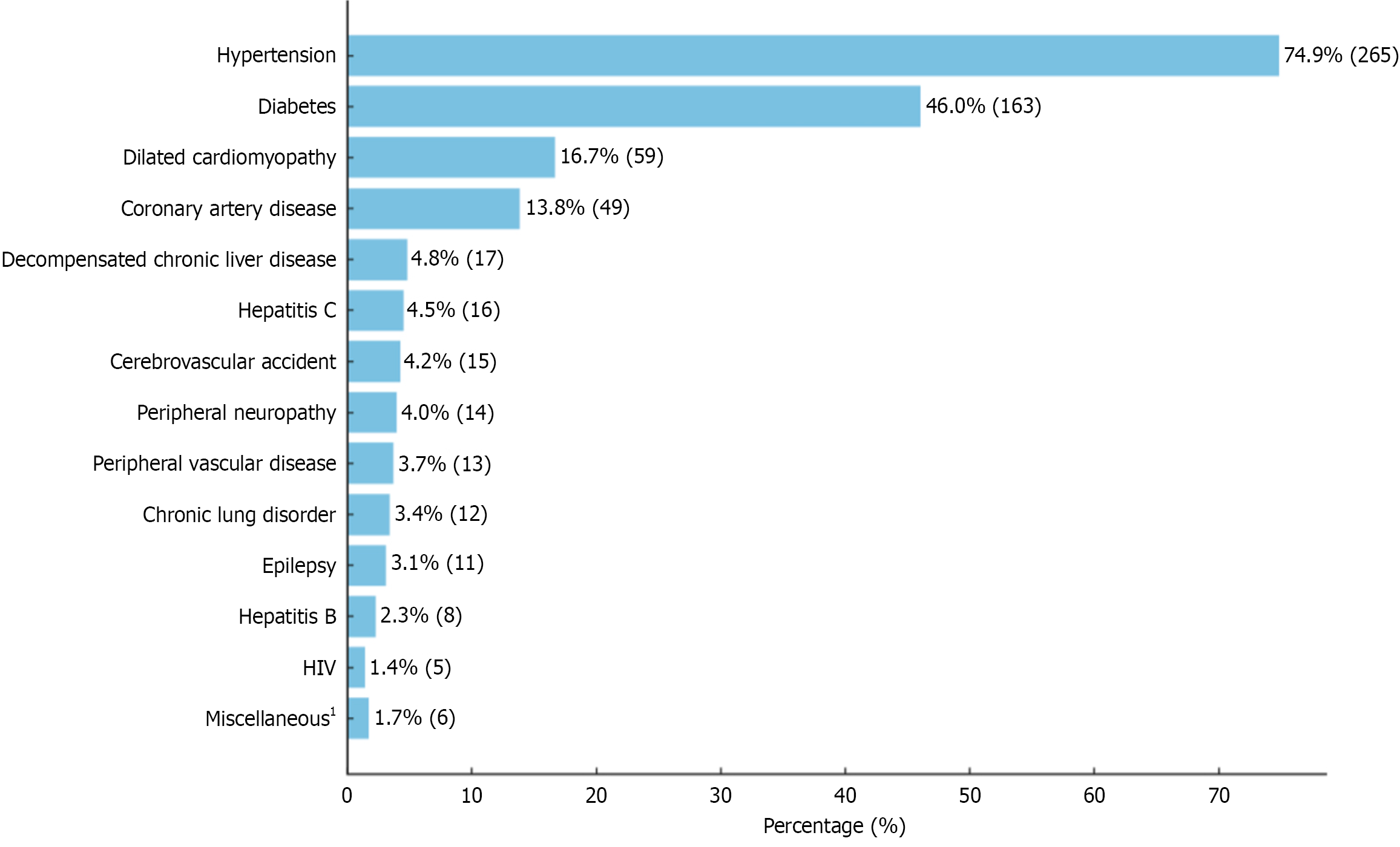

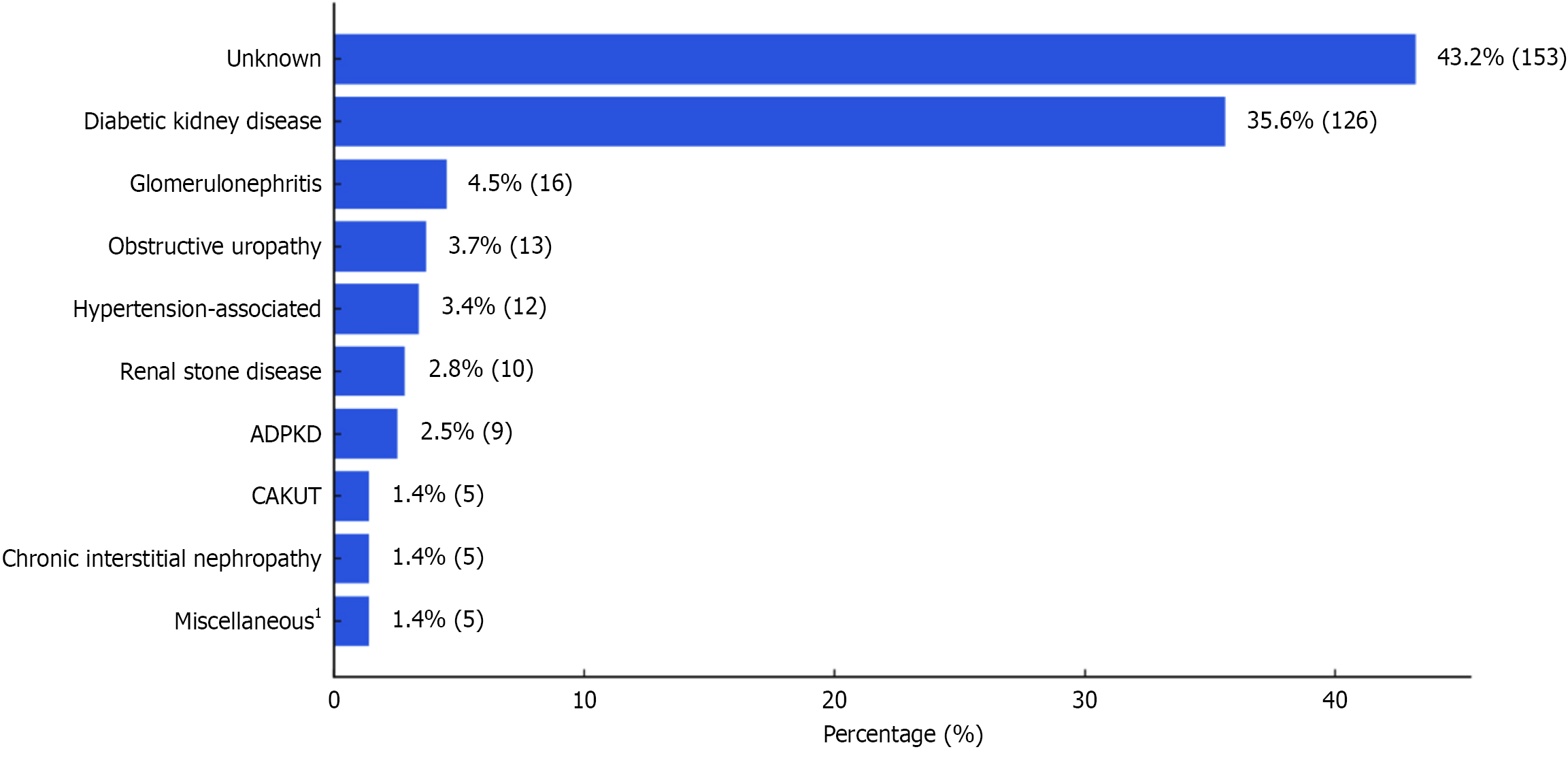

Among 354 patients (mean age 49 years; 58% males), 60.5% had CKD stage 5, and 41.2% were on maintenance dialysis. Hypertension (74.9%) and diabetes (46.0%) were common comorbidities. Diabetic kidney disease was the primary etiology in 35.6%, while 43.2% had unknown causes. Infection (63.0%) was the most frequent cause for ED admission. In-hospital mortality was 29.1% (n = 103). Independent mortality predictors were Glasgow coma scale (GCS) < 15 [hazard ratio (HR): 1.822, P = 0.017], hyperglycemia (HR: 1.641, P = 0.020), and low albumin (HR: 1.270, P = 0.028). Advanced age, Charlson comorbidity Index, quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, and neutrophilia were significant in univariate but not multivariate analysis. CKD stage, dialysis dependency, cardiovascular disease, and neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio were not predictive.

A low GCS, hyperglycemia, and low albumin levels at admission independently predict in-hospital mortality in CKD patients presenting to the ED, warranting early recognition and targeted interventions.

Core Tip: Despite the high burden of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in Indian emergency departments, baseline prognostic markers remain underexplored. This study found a high in-hospital mortality rate among adult patients with CKD. Independent predictors of mortality included a low Glasgow coma scale, hyperglycemia, and low serum albumin at admission. These findings highlight the importance of early risk stratification and targeted interventions to improve short-term survival in acutely ill patients with CKD.

- Citation: Prabhahar A, Vijaykumar NA, Kaur H, Sharma N, Pannu AK. Baseline predictors of in-hospital mortality among patients with chronic kidney disease admitted to the emergency department. World J Nephrol 2025; 14(4): 109382

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-6124/full/v14/i4/109382.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5527/wjn.v14.i4.109382

Despite advances in the management of chronic kidney disease (CKD), it remains a critical global health issue with significant implications for adult mortality[1]. In 2017, CKD was the 12th leading cause of death globally, escalating from the 17th position in 1990, and is projected to become the 5th by 2040[2]. This rising trend persists despite a reduction in cardiovascular-related deaths, which have been historically associated with poor outcomes in advanced CKD[3]. Infections, acute or progressive renal function deterioration, and malignancies are also common causes of CKD-related deaths[4,5]. In low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) such as India, premature deaths in CKD patients also correlate with burgeoning diabetes prevalence, inadequate preventive strategies for high-risk individuals, and suboptimal care for end-stage kidney disease[6-10].

Patients with CKD often have unique challenges in the emergency department (ED) due to associated comorbidities (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, or cardiovascular diseases), diagnostic challenges (e.g., atypical clinical presentations, potential contrast-related complications), and complexity of treatment (e.g., selection or dosing of medications, dialysis-related complications). These patients present to ED with complications that are directly or indirectly related to their underlying renal disease, such as fluid overload, electrolyte imbalances, encephalopathy, life-threatening infections, and cardiovascular disorders[11]. Moreover, in LMIC, a significant portion of CKD patients first encounter specialized nephrology care in the ED during admission with acute illnesses[12]. Such delayed presentations often require intensive care and immediate initiation of dialysis, leading to unfavorable outcomes characterized by a heightened risk of treat

The high mortality rate of CKD patients in the ED setting underscores the urgency of this healthcare challenge. Despite existing research, there remains a significant knowledge gap in understanding the baseline predictors of mortality in this vulnerable population. Identifying these predictors is critical for effective clinical decision-making, prompt diagnosis and treatment, proactive critical care unit transfers, efficient resource allocation, and, ultimately, improved patient outcomes. This study aims to identify readily available clinical and laboratory parameters predictive of all-cause in-hospital mortality in CKD patients at admission to ED.

This retrospective study was conducted at the Acute Care and Emergency Medicine (ACEM) Unit of the Department of Internal Medicine at the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER), Chandigarh (India). We reviewed the case records of all adult patients aged ≥ 18 years diagnosed with CKD admitted from January 2021 to December 2022. A formal sample size calculation was not performed given the retrospective design; however, all eligible patients admitted during the two-year period were included to ensure sufficient statistical power and to capture seasonal variability in illness patterns. PGIMER Chandigarh, a 1948-bedded academic hospital and major tertiary-care referral center, serves a wide catchment across multiple North Indian states, thereby enhancing the generalizability and representativeness of the study population. The ACEM unit manages approximately 120–150 admissions daily, encompassing the emergency rooms (ERs), observation units (OUs), and a high dependency unit (HDU)[15]. After initial stabilization in the ER, patients were either managed in the HDU and OUs, both of which are equipped with 30 high-flow oxygen beds and 15 ventilators, ensuring advanced care for critically ill patients. The study received approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee.

CKD was defined as a sustained estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 of body-surface area for a duration of more than 3 months[16]. The Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes 2024 guidelines classified CKD based on eGFR (mL/minute per 1.73 m2) into five categories: G1: EGFR ≥ 90, G2: EGFR 60-89, G3a: EGFR 45-59, G3b: EGFR 30-44, G4: EGFR 15-29, G5: EGFR < 15 or on dialysis treatment[16].

The clinical details, laboratory parameters, and outcomes of the patients were collected from the case files maintained by the medical record department using a pre-designed data collection form. Patients who left the hospital against medical advice were excluded. To ensure data quality, two authors independently reviewed and extracted information, with dis

The age-adjusted Charlson’s comorbidity index (CCI) was calculated for each patient to assess the severity of comorbid conditions at baseline[16]. We defined shock as systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg or mean arterial pressure < 70 mmHg. Quick sequential organ failure assessment (qSOFA) was calculated in all cases at baseline, comprising the following criteria: Glasgow coma scale (GCS) < 15, systolic blood pressure ≤ 100 mmHg and a respiratory rate ≥ 22 breaths per minute[17]. A qSOFA criteria of ≥ 2 indicates a severe disease.

Various laboratory abnormalities were defined according to the reference values used at PGIMER (Chandigarh) and standard definitions. These included: Hyperglycemia as random plasma glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L at admission, hypoglyce

Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 25.0. Categorical variables were represented as frequency and percentage (n or %), and continuous variables were summarised either as mean ± SD or median with interquartile range (IQR), depending on the normality of data distribution. The normality of data distribution was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, supplemented by visual examination of quantile-quantile plots. The χ² test or Fisher's exact test was conducted for categorical variables, and the Student's unpaired t-test or Mann-Whitney U-test for continuous variables, tailored according to the characteristics of the data. A multivariate Cox-proportion hazard regression analysis was used to detect independent predictors of all-cause in-hospital mortality, calculating the hazard ratio (HR) and a 95%CI. The level of statistical significance was established with a P value threshold of < 0.05 for all tests.

Missing data were minimal and handled using complete case analysis, with no imputation performed.

We screened 393 case records of patients with CKD admitted to ED. Of these, 11 were under 18 years of age and were excluded, along with 28 patients who left against medical advice, resulting in a final sample size of 354. The mean age of the cohort was 48.8 ± 15.5 years (range 18-84), and 28.5% of the patients (n = 101) were 60 years or older. There was a male predominance (57.6%, n = 204). The median CCI of the cohort was 4 (IQR: 3-6). The most common associated medical comorbidities were hypertension (74.9%) and diabetes (46.0%), as detailed in Figure 1.

The median duration of CKD in our cohort was 1 year (IQR: 0.5-3), including > 1 year in approximately three-fourths of the patients (n = 264, 74.6%). The CKD stage distribution was as follows: Stage 1 in 0.6% (n = 2), stage 2 in 11.9% (n = 42), stage 3a in 6.8% (n = 24), stage 3b in 7.3% (n = 26), and stage 4 in 13.0% (n = 46), and stage 5 in 60.5% (n = 214). Regarding dialysis treatment, 41.2% (n = 146) of the study cohort (i.e., 68.2% of the stage 5 patients) were on maintenance dialysis at admission. The most common type of vascular access used was temporary (non-tunneled) hemodialysis catheters (43.8%, n = 64), followed by arteriovenous fistulas (41.8%, n = 61), tunneled hemodialysis catheters (13.0%, n = 19), and peritoneal dialysis catheters (1.4%, n = 2). Figure 2 illustrates the etiological categories of CKD.

The patients usually presented with shortness of breath (41.5%), fever (33.9%), and altered mental status (24.9%). The less common complaints included reduced urine output (9.6%), weakness or fatigue (7.1%), seizures (6.2%), vomiting or anorexia (5.9%), anasarca or generalized body swelling (5.4%), abdominal pain (3.4%), and cough (2.8%). Hypotension was present in 15.0% of the patients at admission. Furthermore, 33.6% had a baseline qSOFA score of ≥ 2.

In this CKD cohort, infection (n = 223, 63.0%) was the most common diagnosis for acute illness requiring ED admissions. Non-infectious disorders (n = 55, 15.5%) were less common. The remaining 21.5% of ED admissions (n = 66) were attributed solely to CKD-related complications. Among infectious causes, respiratory tract infections (n = 81, 22.9%), blood-stream infections or sepsis (n = 51, 14.4%), urinary tract infections (n = 46, 13.0%), and multi-site infections (n = 21, 5.9%) were frequent. Acute non-infectious disorders included cerebrovascular accident (n = 6, 1.7%), acute decompen

The in-hospital mortality rate was 29.1% (n = 103). Baseline clinical parameters associated with mortality on univariate analysis were advanced age, diabetes, a higher CCI score, diabetic kidney disease, altered mental status or low GCS, lower blood pressures, and a qSOFA score ≥ 2, as detailed in Table 1. Table 2 demonstrates laboratory predictors of mortality on univariate analysis. Significant predictors included elevated total leukocyte counts and neutrophils, hyperglycemia, higher aspartate transaminase, and lower serum albumin. In contrast, lower hemoglobin, lower sodium, and higher creatinine were inversely associated with mortality. Of these parameters, GCS < 15 (HR: 1.822, P = 0.017), hyperglycemia (HR: 1.641, P = 0.020), and low albumin (HR: 1.270, P = 0.028) remained independent predictors of mortality on the multivariate Cox regression analysis (Table 3).

| Parameter | Total (n = 354) | Survivor (n = 251) | Died (n = 103) | P value |

| Age (years) | 48.8 ± 15.5 | 47.2 ± 15.9 | 52.7 ± 13.7 | 0.002 |

| Age ≥ 60 years | 101 (28.5) | 69 (27.5) | 32 (31.1) | 0.498 |

| Male gender | 204 (57.6) | 147 (58.6) | 57 (55.3) | 0.577 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 265 (74.9) | 189 (75.3) | 76 (73.8) | 0.786 |

| Diabetes | 163 (46.0) | 103 (41.0) | 60 (58.3) | 0.003 |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 59 (16.7) | 39 (15.5) | 20 (19.4) | 0.374 |

| Coronary artery disease | 49 (13.8) | 30 (12.0) | 19 (18.4) | 0.108 |

| Stroke | 15 (4.2) | 9 (3.6) | 6 (5.8) | 0.342 |

| Decompensated chronic liver disease | 17 (4.8) | 9 (3.6) | 8 (7.8) | 0.105 |

| Hepatitis B or C | 21 (5.9) | 13 (5.2) | 8 (7.8) | 0.349 |

| Charlson’s comorbidity index | 4 (3-6) | 4 (2-6) | 5 (4-6) | 0.003 |

| CKD characteristics | ||||

| CKD etiology unknown | 153 (43.2) | 111 (44.2) | 42 (40.8) | 0.552 |

| Diabetic kidney disease | 126 (35.6) | 79 (31.5) | 47 (45.6) | 0.012 |

| Duration of CKD > 1 year | 264 (74.6) | 190 (75.7) | 74 (71.8) | 0.450 |

| CKD stage 4 or 5 | 260 (73.4) | 183 (72.9) | 77 (74.8) | 0.721 |

| CKD stage 5 | 214 (60.5) | 155 (61.8) | 59 (57.3) | 0.435 |

| Patients on maintenance dialysis | 146 (41.2) | 108 (43.0) | 38 (36.9) | 0.230 |

| Presenting symptoms and signs | ||||

| Shortness of breath | 147 (41.5) | 103 (41.0) | 44 (42.7) | 0.770 |

| Fever | 120 (33.9) | 85 (33.9) | 35 (34.0) | 0.983 |

| Altered mental status | 88 (24.9) | 48 (19.1) | 40 (38.8) | < 0.001 |

| Reduced urine output | 34 (9.6) | 17 (6.8) | 17 (16.5) | 0.005 |

| Generalized weakness or fatigue | 25 (7.1) | 18 (7.2) | 7 (6.8) | 0.900 |

| Vomiting or anorexia | 21 (5.9) | 19 (7.6) | 2 (1.9) | 0.042 |

| Seizures | 22 (6.2) | 15 (6.0) | 7 (6.8) | 0.772 |

| Glasgow coma scale | 13 (15-15) | 15 (15-15) | 13 (8-15) | < 0.001 |

| Glasgow coma scale < 15 | 116 (32.8) | 52 (20.7) | 64 (62.1) | < 0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 132.9 ± 34.4 | 136.9 ± 34.0 | 123.0 ± 33.7 | 0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 79.1 ± 21.9 | 81.5 ± 20.8 | 73.4 ± 23.5 | 0.002 |

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | 70.6 ± 18.1 | 72.8 ± 17.5 | 65.4 ± 18.5 | 0.001 |

| Hypotension | 53 (15.0) | 26 (10.4) | 27 (26.2) | < 0.001 |

| Pulse rate (per minute) | 97.9 ± 18.9 | 96.8 ± 19.2 | 100.5 ± 18.0 | 0.103 |

| Respiratory rate (per minute) | 22.6 ± 4.2 | 22.2 ± 4.1 | 23.9 ± 4.1 | 0.002 |

| qSOFA ≥ 2 | 119 (33.6) | 60 (23.9) | 59 (57.3) | < 0.001 |

| Parameter | Total (n = 354) | Survivor (n = 251) | Died (n = 103) | P value |

| Random plasma glucose (mmol/L) | 6.9 (5.3-10.0) | 6.6 (5.4-9.3) | 7.6 (5.1-12.8) | 0.133 |

| Hyperglycemia | 73 (20.6) | 39 (15.5) | 34 (33.0) | < 0.001 |

| Hypoglycemia | 40 (11.3) | 24 (9.6) | 16 (15.5) | 0.107 |

| Serum sodium (mmol/L) | 134.1 ± 7.8 | 133.4 ± 7.3 | 135.6 ± 8.8 | 0.015 |

| Hyponatremia | 166 (46.9) | 123 (49.0) | 43 (41.7) | 0.214 |

| Serum potassium (mmol/L) | 5.0 ± 1.2 | 5.1 ± 1.1 | 5.0 ± 1.3 | 0.955 |

| Severe hyperkalemia | 42 (11.9) | 31 (12.4) | 11 (10.7) | 0.659 |

| Blood urea (mmol/L) | 57.3 (37.5-79.8) | 56.8 (37.8-81.0) | 58.6 (36.8-79.3) | 0.949 |

| Serum creatinine (μmol/L) | 690 (468-963) | 725 (530-1016) | 530 (416-805) | < 0.001 |

| Serum bilirubin (μmol/L) | 8.6 (6.8-13.7) | 8.6 (6.8-12.0) | 10.3 (5.1-15.4) | 0.149 |

| Aspartate transaminase (U/L) | 27 (18-54) | 25 (17-49) | 35 (21-72) | 0.003 |

| Alanine transaminase (U/L) | 22 (11-39) | 22 (11-39) | 21 (13.5-43) | 0.454 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 133 (97.5-211.25) | 130 (94-187) | 165 (113.5-272) | 0.093 |

| Total serum protein (g/L) | 62.9 ± 9.2 | 63.9 ± 9.0 | 60.6 ± 9.4 | 0.004 |

| Serum albumin (g/L) | 29.1 ± 7.0 | 29.9 ± 6.6 | 27.1 ± 7.5 | 0.001 |

| Serum calcium (mmol/L) | 2.06 ± 0.31 | 2.05 ± 0.31 | 2.08 ± 0.30 | 0.540 |

| Serum phosphorus (mmol/L) | 1.81 ± 0.68 | 1.80 ± 0.69 | 1.80 ± 0.64 | 0.724 |

| Serum magnesium (mmol/L) | 1.06 ± 0.21 | 1.06 ± 0.22 | 1.04 ± 0.18 | 0.582 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 75.6 ± 22.2 | 73.4 ± 21.8 | 81.1 ± 22.4 | 0.003 |

| Platelets (per μL) | 166000 (103000-244000) | 166000 (108000-248000) | 147000 (78000-227000) | 0.864 |

| Total leukocyte count (per μL) | 11400 (7600-17525) | 10900 (7400-16300) | 13200 (8800-20000) | 0.023 |

| Leukocytosis | 184 (52.0) | 123 (49.0) | 61 (59.2) | 0.080 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 84 (76-88) | 82 (74-88) | 86 (78.5-89.5) | 0.046 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 8 (5-13) | 8 (5-13) | 7 (4-12.75) | 0.977 |

| Neutrophil lymphocyte ratio | 10.9 (5.75-18.0) | 10.25 (5.5-17.75) | 12.4 (5.9-22.1) | 0.220 |

| Parameter | Hazard ratio (95%CI) | P value |

| Age (years) | 1.001 (0.991-1.014) | 0.636 |

| Diabetes | 0.989 (0.671-1.458) | 0.956 |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 0.970 (0.889-1.059) | 0.498 |

| Glasgow coma scale < 15 | 1.822 (1.112-2.984) | 0.017 |

| Hypotension | 0.682 (0.417-1.117) | 0.129 |

| qSOFA ≥ 2 | 0.953 (0.576-1.574) | 0.850 |

| Hyperglycemia | 1.641 (1.080-2.494) | 0.020 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 0.989 (0.975-1.003) | 0.130 |

| Serum albumin (g/L) | 1.270 (1.026-1.572) | 0.028 |

The median duration of hospital stay for the cohort was 4 days (IQR: 2-7, range: 0-94) and was similar in survivor and non-survivor groups, i.e., 4 (IQR: 3-7) vs 4 (IQR: 2-7), P = 0.121.

This extensive retrospective study underscores the significant mortality risk among adult Indian patients with CKD requiring ED admission. Most patients presented with advanced CKD, with hypertension and diabetes as common comorbidities. Strong predictors of all-cause in-hospital mortality identified at admission included low GCS, hyper

We observed a high mortality rate among CKD patients admitted to the ED, consistent with previous reports from LMIC[18,19]. These patients are typically older and have multiple comorbidities compared to the general ED population, which poses unique challenges in diagnosis, treatment, and medication management, often necessitating a multidisciplinary team management[15]. In our cohort, several chronic risk markers showed association with mortality, but did not retain significance as independent predictors. This likely reflects the greater prognostic relevance of acute physiological parameters, such as altered mental status, hyperglycemia, and hypoalbuminemia, which capture the severity of illness more directly than baseline characteristics like age, diabetes, or comorbidity indices. Similar findings have been reported in other CKD cohorts, where dynamic clinical variables outperform static risk scores in predicting short-term outcomes[20].

The prevalence of comorbidities in our study was comparable to recent CKD data from India[10,21]. Among these, diabetes emerged as a major contributor to mortality. While previous studies have linked diabetes to long-term cardio

Our ED cohort predominantly included patients with advanced CKD, with nearly three-quarters in stages 4 or 5 and more than two-thirds of those with stage 5 receiving maintenance dialysis. This narrow distribution of disease severity may have diminished the prognostic significance of baseline serum creatinine or CKD stage, unlike population-based studies where a broader CKD spectrum allows clearer stratification[27]. Similarly, mortality rates were comparable between patients with and without prior dialysis or prolonged disease duration. These findings suggest that once patients with CKD reach the threshold of acute decompensation requiring emergency care, baseline renal parameters may be less informative than acute clinical indicators. This reinforces the limited prognostic utility of static CKD-related variables in the ED setting.

The most common presenting features in our cohort were shortness of breath, fever, and altered mental status, consistent with previous ED-based studies of CKD patients[18]. Among these symptoms, altered sensorium—particularly reflected by a GCS score < 15—was the strongest predictor of mortality. This likely reflects the burden of acute metabolic encephalopathy, septic encephalopathy, hypertensive crises, and cerebrovascular events frequently encountered in decompensated CKD[7,18]. Underlying cognitive dysfunction, common in advanced CKD, may further increase susceptibility to acute mental status changes[7,28]. Although other markers of systemic illness, such as hypotension, tachypnea, and qSOFA ≥ 2, were associated with increased mortality in univariate analysis, they did not retain independent significance. This may be due to acute brain dysfunction being a stronger predictor than cardio-respiratory dysfunction in the multivariate model.

Low serum albumin is a common and clinically important finding in advanced CKD. Its etiology is multifactorial, often reflecting malnutrition, anorexia, chronic inflammation, urinary protein loss—particularly in diabetic kidney disease or glomerulonephritis[29,30]. Chronic inflammation, a hallmark of CKD, not only suppresses albumin synthesis but also enhances its catabolism. Dialysis-related losses further contribute to hypoalbuminemia. Correlating with previous studies, low serum albumin was a strong independent predictor of mortality in our cohort, likely serving as a surrogate of malnutrition-inflammation-atherosclerosis syndrome frequently observed in CKD[29,30]. This syndrome exemplifies the complex interplay between nutritional depletion, systemic inflammation, and cardiovascular risk. In addition, hypoalbuminemia may impair host immune response, increasing susceptibility to severe infections. These findings highlight that serum albumin is not merely a nutritional marker but also a proxy for overall illness severity. Thus, improving outcomes requires addressing the underlying causes rather than attempting to normalize albumin levels alone.

Given that CKD is a chronic inflammatory state, previous studies have linked inflammatory markers such as leucocytosis, neutrophilia, and elevated NLR with adverse outcomes[31,32]. However, in our cohort, these markers did not emerge as significant prognostic factors. Notably, while NLR has been associated with disease progression and mortality in outpatients with early-stage CKD, and a recent meta-analysis reported its association with all-cause mortality in hemodialysis patients without infection, its prognostic relevance appears limited in ED setting[31,32]. This discrepancy suggests that in acutely ill patients, the utility of inflammatory markers such as NLR may be diminished due to the confounding effects of multiple concurrent physiological stressors.

Anemia is a well-recognized complication of CKD and contributes to adverse outcomes by reducing oxygen delivery, impairing immune function, and increasing cardiovascular strain[33,34]. In our cohort, lower hemoglobin levels were associated with increased in-hospital mortality, likely reflecting physiological compromise and the burden of underlying illness. Conversely, patients with relatively preserved hemoglobin levels may represent a subgroup with better nutritional status, lower systemic inflammation, and less advanced disease, which may partly explain their improved survival[33,34]. Similarly, lower serum sodium was associated with higher mortality in our study. Hyponatremia in CKD may reflect fluid overload, systemic inflammation, or impaired homeostatic response during acute illness. This finding is consistent with previous studies showing that dysnatremia, particularly hyponatremia, is associated with poor outcomes in both critically ill and dialysis patients[35].

In our ED cohort, infection-related emergencies were more prevalent than non-infectious illnesses, a finding consistent with patterns reported from other LMIC, where patients with advanced CKD are particularly vulnerable to infections[18,36]. In line with previous reports, respiratory and urinary tract infections were common. Notably, we observed a higher incidence of bloodstream infections, which may be attributable to the widespread use of non-tunneled catheters for vascular access among patients on maintenance dialysis[37]. In addition, a substantial number of ED admissions were driven by preventable or poorly managed CKD-related complications, underscoring missed opportunities for earlier intervention. These findings highlight the urgent need for robust public health strategies focused on CKD screening, early management, and infection prevention, particularly in resource-limited settings.

The study has several limitations. First, its single-center design, retrospective nature, and the referral bias inherent to a tertiary-care hospital may limit the generalizability of our findings. Validation through multicenter prospective studies is warranted. Second, several potentially important prognostic variables, such as body mass index, albuminuria, serum C-reactive protein levels, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide, and echocardiographic findings, were not consistently available and were therefore excluded from the mortality prediction analysis. Lastly, the relatively low frequency of cardiac emergencies such as myocardial infarction likely reflects institutional protocol that mandate immediate transfer of these patients to specialized coronary care units, thus affecting the overall ED spectrum captured in this cohort.

The study highlights the high in-hospital mortality among adult Indian patients with CKD requiring ED admissions. At admission, a low GCS, hyperglycemia, and low serum albumin were strong predictors of mortality, underscoring the need for early identification and prompt intervention targeting these high-risk features. The findings also reinforce the importance of integrated, multi-faceted strategies to reduce preventable CKD-related complications and ED presentations. Future multicenter studies and prospective validation cohorts are warranted to confirm these predictors across diverse populations and healthcare settings, and to inform standardized risk stratification models for use in acute care.

The authors thank Mrs. Sunaina Verma for statistical assistance.

| 1. | Kobo O, Abramov D, Davies S, Ahmed SB, Sun LY, Mieres JH, Parwani P, Siudak Z, Van Spall HGC, Mamas MA. CKD-Associated Cardiovascular Mortality in the United States: Temporal Trends From 1999 to 2020. Kidney Med. 2023;5:100597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Luyckx VA, Al-Aly Z, Bello AK, Bellorin-Font E, Carlini RG, Fabian J, Garcia-Garcia G, Iyengar A, Sekkarie M, van Biesen W, Ulasi I, Yeates K, Stanifer J. Sustainable Development Goals relevant to kidney health: an update on progress. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2021;17:15-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Grams ME, Coresh J, Matsushita K, Ballew SH, Sang Y, Surapaneni A, Alencar de Pinho N, Anderson A, Appel LJ, Ärnlöv J, Azizi F, Bansal N, Bell S, Bilo HJG, Brunskill NJ, Carrero JJ, Chadban S, Chalmers J, Chen J, Ciemins E, Cirillo M, Ebert N, Evans M, Ferreiro A, Fu EL, Fukagawa M, Green JA, Gutierrez OM, Herrington WG, Hwang SJ, Inker LA, Iseki K, Jafar T, Jassal SK, Jha V, Kadota A, Katz R, Köttgen A, Konta T, Kronenberg F, Lee BJ, Lees J, Levin A, Looker HC, Major R, Melzer Cohen C, Mieno M, Miyazaki M, Moranne O, Muraki I, Naimark D, Nitsch D, Oh W, Pena M, Purnell TS, Sabanayagam C, Satoh M, Sawhney S, Schaeffner E, Schöttker B, Shen JI, Shlipak MG, Sinha S, Stengel B, Sumida K, Tonelli M, Valdivielso JM, van Zuilen AD, Visseren FLJ, Wang AY, Wen CP, Wheeler DC, Yatsuya H, Yamagata K, Yang JW, Young A, Zhang H, Zhang L, Levey AS, Gansevoort RT; Writing Group for the CKD Prognosis Consortium. Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate, Albuminuria, and Adverse Outcomes: An Individual-Participant Data Meta-Analysis. JAMA. 2023;330:1266-1277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 65.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rai NK, Wang Z, Drawz PE, Connett J, Murphy DP. CKD Progression Risk and Subsequent Cause of Death: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Kidney Med. 2023;5:100604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Singh AK, Acharya A, Carroll K, Lopes RD, Mccausland FR, Mulloy L, Perkovic V, Solomon S, Waikar SS, Wanner C, Wong MG, Cobitz AR, Mallett SA, Shaddinger BC, Mcmurray JJV. Causes of death in patients with chronic kidney disease: insights from the ASCEND-D and ASCEND-ND cardiovascular outcomes trials. European Heart J. 2022;43. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Anjana RM, Unnikrishnan R, Deepa M, Pradeepa R, Tandon N, Das AK, Joshi S, Bajaj S, Jabbar PK, Das HK, Kumar A, Dhandhania VK, Bhansali A, Rao PV, Desai A, Kalra S, Gupta A, Lakshmy R, Madhu SV, Elangovan N, Chowdhury S, Venkatesan U, Subashini R, Kaur T, Dhaliwal RS, Mohan V; ICMR-INDIAB Collaborative Study Group. Metabolic non-communicable disease health report of India: the ICMR-INDIAB national cross-sectional study (ICMR-INDIAB-17). Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2023;11:474-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 292] [Article Influence: 97.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bello AK, Okpechi IG, Osman MA, Cho Y, Htay H, Jha V, Wainstein M, Johnson DW. Epidemiology of haemodialysis outcomes. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2022;18:378-395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 336] [Article Influence: 84.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ke C, Liang J, Liu M, Liu S, Wang C. Burden of chronic kidney disease and its risk-attributable burden in 137 low-and middle-income countries, 1990-2019: results from the global burden of disease study 2019. BMC Nephrol. 2022;23:17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Feng X, Hou N, Chen Z, Liu J, Li X, Sun X, Liu Y. Secular trends of epidemiologic patterns of chronic kidney disease over three decades: an updated analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. BMJ Open. 2023;13:e064540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Dare AJ, Fu SH, Patra J, Rodriguez PS, Thakur JS, Jha P; Million Death Study Collaborators. Renal failure deaths and their risk factors in India 2001-13: nationally representative estimates from the Million Death Study. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5:e89-e95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ronksley PE, Scory TD, McRae AD, MacRae JM, Manns BJ, Lang E, Donald M, Hemmelgarn BR, Elliott MJ. Emergency Department Use Among Adults Receiving Dialysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7:e2413754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Dhanorkar M, Prasad N, Kushwaha R, Behera M, Bhaduaria D, Yaccha M, Patel M, Kaul A. Impact of Early versus Late Referral to Nephrologists on Outcomes of Chronic Kidney Disease Patients in Northern India. Int J Nephrol. 2022;2022:4768540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cho A, Jeong SA, Park HC, Yoon HE, Kim J, Lee YK, Yoo KD; Korean Society of Nephrology Disaster Preparedness and Response Committee. Emergency department visits for patients with end-stage kidney disease in Korea: registry data from the National Emergency Department Information System 2019-2021. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2025;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chang CH, Fan PC, Kuo G, Lin YS, Tsai TY, Chang SW, Tian YC, Lee CC. Infection in Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease and Subsequent Adverse Outcomes after Dialysis Initiation: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Sci Rep. 2020;10:2938. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Pannu AK, Saroch A, Kumar M, Behera A, Nayyar GS, Sharma N. Quantification of chronic diseases presenting in the Emergency Department and their disposition outcomes: A hospital-based cross-sectional study in north India. Trop Doct. 2022;52:276-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2024;105:S117-S314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2198] [Article Influence: 1099.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, Antonelli M, Coopersmith CM, French C, Machado FR, Mcintyre L, Ostermann M, Prescott HC, Schorr C, Simpson S, Wiersinga WJ, Alshamsi F, Angus DC, Arabi Y, Azevedo L, Beale R, Beilman G, Belley-Cote E, Burry L, Cecconi M, Centofanti J, Coz Yataco A, De Waele J, Dellinger RP, Doi K, Du B, Estenssoro E, Ferrer R, Gomersall C, Hodgson C, Møller MH, Iwashyna T, Jacob S, Kleinpell R, Klompas M, Koh Y, Kumar A, Kwizera A, Lobo S, Masur H, McGloughlin S, Mehta S, Mehta Y, Mer M, Nunnally M, Oczkowski S, Osborn T, Papathanassoglou E, Perner A, Puskarich M, Roberts J, Schweickert W, Seckel M, Sevransky J, Sprung CL, Welte T, Zimmerman J, Levy M. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47:1181-1247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 295] [Cited by in RCA: 2855] [Article Influence: 571.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sylvanus E, Sawe HR, Muhanuzi B, Mulesi E, Mfinanga JA, Weber EJ, Kilindimo S. Profile and outcome of patients with emergency complications of renal failure presenting to an urban emergency department of a tertiary hospital in Tanzania. BMC Emerg Med. 2019;19:11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Gómez de la Torre-Del Carpio A, Bocanegra-Jesús A, Guinetti-Ortiz K, Mayta-Tristán P, Valdivia-Vega R. Early mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease who started emergency haemodialysis in a Peruvian population: Incidence and risk factors. Nefrologia (Engl Ed). 2018;38:425-432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | McArthur E, Bota SE, Sood MM, Nesrallah GE, Kim SJ, Garg AX, Dixon SN. Comparing Five Comorbidity Indices to Predict Mortality in Chronic Kidney Disease: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2018;5:2054358118805418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kumar V, Yadav AK, Sethi J, Ghosh A, Sahay M, Prasad N, Varughese S, Parameswaran S, Gopalakrishnan N, Kaur P, Modi GK, Kamboj K, Kundu M, Sood V, Inamdar N, Jaryal A, Vikrant S, Nayak S, Singh S, Gang S, Baid-Agrawal S, Jha V. The Indian Chronic Kidney Disease (ICKD) study: baseline characteristics. Clin Kidney J. 2022;15:60-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Anjana RM, Unnikrishnan R, Mugilan P, Jagdish PS, Parthasarathy B, Deepa M, Loganathan G, Kumar RA, Rahulashankiruthiyayan T, Uma Sankari G, Venkatesan U, Mohan V, Shanthi Rani CS. Causes and predictors of mortality in Asian Indians with and without diabetes-10 year follow-up of the Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study (CURES - 150). PLoS One. 2018;13:e0197376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Samarasinghe A, Wong G, Teixeira-Pinto A, Johnson DW, Hawley C, Pilmore H, Mulley WR, Roberts MA, Polkinghorne KR, Boudville N, Davies CE, Viecelli AK, Ooi E, Larkins NG, Lok C, Lim WH. Association between diabetic status and risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality on dialysis following first kidney allograft loss. Clin Kidney J. 2024;17:sfad245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Pannu AK, Saroch A, Singla V, Sharma N, Dutta P, Jain A, Angrup A. Clinical spectrum, etiology and outcome of infectious disease emergencies in adult diabetic patients in northern India. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14:921-925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Heo GY, Koh HB, Kim HW, Park JT, Yoo TH, Kang SW, Kim J, Kim SW, Kim YH, Sung SA, Oh KH, Han SH. Glycemic Control and Adverse Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Results from KNOW-CKD. Diabetes Metab J. 2023;47:535-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Corrao S, Nobili A, Natoli G, Mannucci PM, Perticone F, Pietrangelo A, Argano C; REPOSI Investigators. Hyperglycemia at admission, comorbidities, and in-hospital mortality in elderly patients hospitalized in internal medicine wards: data from the RePoSI Registry. Acta Diabetol. 2021;58:1225-1236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Matsushita K, van der Velde M, Astor BC, Woodward M, Levey AS, de Jong PE, Coresh J, Gansevoort RT; Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium. Association of estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in general population cohorts: a collaborative meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:2073-2081. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3261] [Cited by in RCA: 3195] [Article Influence: 199.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Pal S, Sharma N, Singh SM, Kumar S, Pannu AK. A prospective cohort study on predictors of mortality of delirium in an emergency observational unit. QJM. 2021;114:246-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Alves FC, Sun J, Qureshi AR, Dai L, Snaedal S, Bárány P, Heimbürger O, Lindholm B, Stenvinkel P. The higher mortality associated with low serum albumin is dependent on systemic inflammation in end-stage kidney disease. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0190410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Sanz-García C, Rodríguez-García M, Górriz-Teruel JL, Martín-Carro B, Floege J, Díaz-López B, Palomo-Antequera C, Sánchez-Alvarez E, Gómez-Alonso C, Fernández-Gómez J, Hevia-Suárez MÁ, Navarro-González JF, Arenas MD, Locatelli F, Zoccali C, Ferreira A, Alonso-Montes C, Cannata-Andía JB, Carrero JJ, Fernández-Martín JL; COSMOS. Differences in association between hypoalbuminaemia and mortality among younger versus older patients on haemodialysis. Clin Kidney J. 2025;18:sfae339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Yoshitomi R, Nakayama M, Sakoh T, Fukui A, Katafuchi E, Seki M, Tsuda S, Nakano T, Tsuruya K, Kitazono T. High neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio is associated with poor renal outcomes in Japanese patients with chronic kidney disease. Ren Fail. 2019;41:238-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Tanic AS, Rinaldi FX, Polanit VL, Kalaij AGI. High Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio as a Predictor of All-Cause and Cardiovascular-Related Mortality in Hemodialysis Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Indian J Nephrol. 2025;0:1-9. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 33. | Young EW, Wang D, Kapke A, Pearson J, Turenne M, Robinson BM, Huff ED. Hemoglobin and Clinical Outcomes in Hemodialysis: An Analysis of US Medicare Data From 2018 to 2020. Kidney Med. 2023;5:100578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Kosugi T, Hasegawa T, Imaizumi T, Nishiwaki H, Honda H, Ito Y, Tsuruya K, Abe M, Hanafusa N, Kuragano T. Association between hemoglobin level and mortality in patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis: a nationwide dialysis registry in Japan. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2025;29:831-842. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Sun L, Hou Y, Xiao Q, Du Y. Association of serum sodium and risk of all-cause mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease: A meta-analysis and sysematic review. Sci Rep. 2017;7:15949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 36. | Mujtaba F, Ahmad A, Dhrolia M, Qureshi R, Nasir K. Causes of Emergency Department Visits Among End-Stage Kidney Disease Patients on Maintenance Hemodialysis in Pakistan: A Single-Center Study. Cureus. 2022;14:e33004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Zhang HH, Cortés-Penfield NW, Mandayam S, Niu J, Atmar RL, Wu E, Chen D, Zamani R, Shah MK. Dialysis Catheter-related Bloodstream Infections in Patients Receiving Hemodialysis on an Emergency-only Basis: A Retrospective Cohort Analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68:1011-1016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/