Published online Aug 12, 2015. doi: 10.5501/wjv.v4.i3.277

Peer-review started: January 8, 2015

First decision: March 6, 2015

Revised: July 2, 2015

Accepted: July 21, 2015

Article in press: July 23, 2015

Published online: August 12, 2015

Processing time: 217 Days and 13.2 Hours

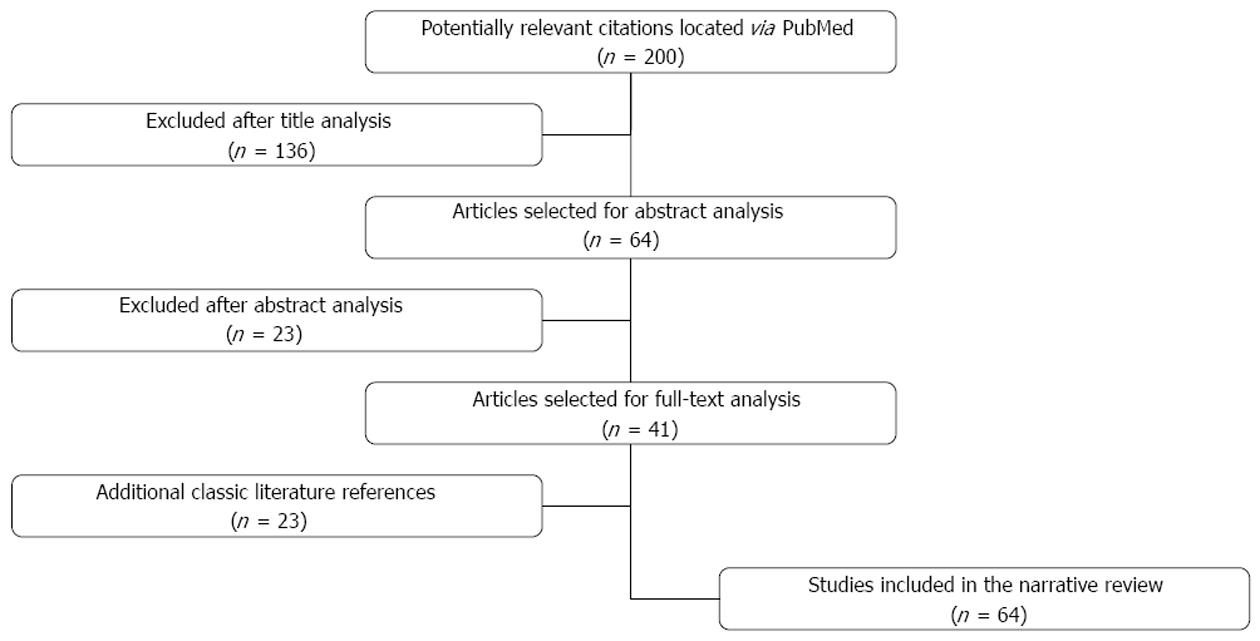

The availability of highly potent antiretroviral treatment during the last decades has transformed human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection into a chronic disease. Children that were diagnosed during the first months or years of life and received treatment, are living longer and better and are presently reaching adolescence and adulthood. Perinatally HIV-infected adolescents (PHIV) and young adults may present specific clinical, behavior and social characteristics and demands. We have performed a literature review about different aspects that have to be considered in the care and follow-up of PHIV. The search included papers in the MEDLINE database via PubMed, located using the keywords “perinatally HIV-infected” AND “adolescents”. Only articles published in English or Portuguese from 2003 to 2014 were selected. The types of articles included original research, systematic reviews, and quantitative or qualitative studies; case reports and case series were excluded. Results are presented in the following topics: “Puberal development and sexual maturation”, “Growth in weight and height”, “Bone metabolism during adolescence”, “Metabolic complications”, “Brain development, cognition and mental health”, “Reproductive health”, “Viral drug resistance” and “Transition to adult outpatient care”. We hope that this review will support the work of pediatricians, clinicians and infectious diseases specialists that are receiving these subjects to continue treatment.

Core tip: We have performed a literature review about different aspects that have to be considered in the care and follow-up of perinatally human immunodeficiency virus-infected adolescents and young adults. Articles reporting original research, systematic reviews, quantitative or qualitative studies and published from 2003 to 2014 were selected. Results are presented in the following topics: “Puberal development and sexual maturation”, “Growth in weight and height”, “Bone metabolism during adolescence”, “Metabolic complications”, “Brain development, cognition and mental health”, “Reproductive health”, “Viral drug resistance” and “Transition to adult outpatient care”.

- Citation: Cruz MLS, Cardoso CA. Perinatally infected adolescents living with human immunodeficiency virus (perinatally human immunodeficiency virus). World J Virology 2015; 4(3): 277-284

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3249/full/v4/i3/277.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5501/wjv.v4.i3.277

The World Health Organization defines adolescence as the period in life from ages 10 to 19, i.e., the second decade of life[1]. Puberty is the main biological component of adolescence and results in physical and mental changes due to the reactivation of the neurohormonal mechanisms of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal/gonadal axis, as well as those determined by the historical context and sociocultural conditions of each individual.

The body image of adolescents is affected by the changes in their body attributes (hair, breasts) and functioning (ability to have sexual intercourse, menarche, voice change); similarity to the adult body; significance of recognizing the other; and interaction with others with bodies that can now awaken desire, which now become desirable and desiring[2]. This process also includes parallel losses that must be properly assimilated: loss of the childhood body, childhood parents, and childhood identity[3].

Normal adolescence syndrome is the name given to the set of characteristics proper to this developmental period, which include the following: search for oneself and one’s identity, group tendency, the need to intellectualize and fantasize, religious crisis, temporal displacement, development of sexuality, assertive social attitude, successive contradictions, progressive detachment from parents, and continuous mood swings[4].

As a result of the aforementioned features, adolescents are liable to increased exposure to alcohol and drug use, vulnerability to traffic accidents, fights, misdemeanors, and difficulty in maintaining appropriate self-care activities, such as the use of condoms, adoption of harm reduction measures, and proper use of medications. These characteristics, together with issues related to the social vulnerability of youth, contribute to the significant number of infections by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) that occur during this stage of life[5].

There is no stereotype universally representative of adolescents perinatally infected by HIV (PHIV). Some HIV-infected children reach adolescence fully aware of their condition, while others do not. In some cases, they are the only family member with an HIV infection, or they belong to families with good adherence to treatment and, thus, go through childhood having benefited from the full effects of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART): viral suppression, adequate growth, and good quality of life. In other cases, treatment is irregularly performed, and the affected youths exhibit advanced forms of the disease in adolescence, eventually requiring new drugs to ensure their survival. Other youths mature in institutions, where antiretroviral therapy (ART) may or may not be properly performed. In short, the living conditions and treatment history should be thoroughly investigated in the case of PHIV adolescents, as non-adherence to treatment is associated with the emergence of viral drug resistance, with the consequent need to change the antiretroviral regimen, and it is also associated with situations and characteristics typical of adolescence[6].

We should bear in mind that, independently of their personal history, we are interacting with individuals who tend to have a defiant attitude and who exhibit some degree of emotional instability. This situation is the context within which we must investigate adolescents’ awareness of their condition and treatment. In many cases, concepts such as HIV, CD4, or viral load are too abstract to be easily understood, and adolescents tend to be more concerned with their transforming bodies, their losses and gains[7].

Thus, the professionals who provide care to PHIV youths should feel an affinity with adolescents. Although pediatricians are trained to handle adolescents, the ideal situation is that of a multidisciplinary staff that is available to meet the peculiar demands posed by adolescent care in an integrated manner[8].

Adolescents’ caregivers should participate in all aspects of treatment, including the moment when diagnosis is communicated, therapeutic decision-making, and adherence to treatment. Healthcare professionals should be receptive to the caregivers’ insecurities, doubts, fears, and anguish, which might appear at different times during follow-up.

The staff should assume that the adolescents’ families have the skills and conditions to help them cope with their problems and, thus, should help the relatives to become aware of their resources and possibilities and emphasize their positive aspects, helping them to feel increasingly more self-assured and competent. To establish a partnership with the patients’ relatives is the best strategy in the terms of health or education actions or prevention; it is an efficient, positive, productive, and inclusive approach that increases the opportunities to promote changes.

This study consisted of a literature review of articles included in the MEDLINE database via PubMed, located using the keywords “perinatally HIV-infected” AND “adolescents”. Only articles published in English or Portuguese from 2003 to 2014 were selected. The types of articles included original research, systematic reviews, and quantitative or qualitative studies; case reports and case series were excluded.

The application of the aforementioned criteria located 200 articles based on their titles. The abstracts of 64 of such articles were analyzed, which resulted in 41 articles selected for full-text analysis and data extraction. In addition, classic literature references considered relevant for the subject of interest were included. As a result, a total of 64 articles were included in this review. Figure 1 shows the flow chart of article selection.

The body changes that are characteristic of puberty include remarkable physical growth and sexual maturation. According to Marshall and Tanner, puberty is characterized by acceleration followed by cessation of growth, changes in the amount and distribution of fat, and development of the gonads and secondary sex characteristics[9,10].

The sequence of body changes that constitute sexual maturation comprises the development of the gonads, reproductive organs, and sex characteristics. Thelarche is the beginning of breast development in girls; gynecomastia is the enlargement of the breast tissue in boys; pubarche refers to the first appearance of pubic hair, menarche to the first menstrual cycle, semenarche to the first ejaculation, and sexarche to the first sexual intercourse.

Just as in other chronic diseases, HIV infection acquired in the perinatal period also affects sexual maturation. This interference might result from direct virus action, secondary infections, nutritional disorders, and the action of cytokines. The delay in sexual maturation seems to be greater in the later pubertal stages[11,12].

One observational study conducted in the United States found a significant delay of pubertal onset in a group of 2086 adolescents with vertically transmitted HIV infection compared to uninfected youths born from HIV-infected mothers[13].

Slow weight gain and growth deficits are common among children with vertically transmitted HIV infection. These children exhibit early and progressive reductions of linear growth and body mass index, in addition to sustained deficit in anthropometric indexes compared to non-infected individuals[14,15]. These disorders, starting in childhood, might continue into adolescence. Weight loss is common among HIV-infected individuals, independent of the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), and it seems to have a multifactorial etiology.

Weight loss occurs early in the course of infection, preceding the manifestation of significant compromise of the immune system[16]. Growth failure is a well-known indicator of disease progression among HIV-infected children and adolescents and usually precedes the decrease of CD4+ cells. Improvement of growth parameters might be used as a measure of HAART efficacy; control of viral replication exerts a positive effect on the weight and height[17].

Deficits in growth precede and may contribute to the onset of immunodeficiency and opportunistic infections in HIV-infected individuals[18].

The differences in growth patterns are probably due to differences in the manifestations of the disease in HIV-infected children and adolescents; growth delay is greater in patients with viral loads above 100000 copies/mL[19].

The final height of individuals with vertically transmitted HIV infection is usually shorter than the target height. This fact suggests that the height loss accumulated throughout childhood and adolescence might influence the final height in that population[20].

Puberty is a significant period vis-à-vis the acquisition of adequate bone mass. Some of the factors that influence normal bone mineralization are as follows: calcium intake, vitamin D levels, physical activity, hormones, genetic factors, and nutritional status[21]. The adolescent growth spurt is characterized by large bone mass accumulation; the incidence of fractures due to relative bone fragility is high as a result of the dissociation between bone expansion and mineralization[22]. The peak of bone mineralization corresponds to the accumulation of calcium in this tissue. The bone mineral density (BMD) decreases before the adolescent growth spurt, and it increases over the subsequent four years. The peak calcium accretion rate was found to occur at a median age of 12.5 years old in girls and 14 years old in boys[23].

In the current scenario of HIV-infection in growing and developing children, characterized by increased survival and prolonged ART use, the long-term impact on the children’s bone metabolism is not well known[24]. The BMD is lower in HIV-infected children and adolescents compared to the non-infected population[25]. Children using HAART exhibit complications resulting from low BMD[26,27]. These complications are potentially more severe in adolescents than adults due to the adolescent growth spurt and puberty[27].

The etiology of low BMD is multifactorial and might be directly related to the virus, ART, comorbidities, or factors unrelated to HIV infection. Periodic BMD testing is indicated during adolescence, and youths found to have low BMD should be instructed to perform high-impact exercises and use calcium and vitamin D supplements[28].

The long-term benefits of HAART are widely known. Increasing numbers of children with vertically transmitted HIV infection are reaching adulthood and, thus, becoming chronically ill adults[27]. In addition to its impact on the survival of this population, prolonged HAART also seems to have cardioprotective effects in HIV-infected children and adolescents[29]. However, as part of this scenario of improved survival, many youths develop severe metabolic complications, including lipodystrophy, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, lactic acidosis, and bone mass loss. Dyslipidemia, which is mainly associated with the use of protease inhibitors, may increase the risk of cardiovascular disease in adulthood[27].

Chokephaibulkit et al[30] found that the levels of parathyroid hormone were significantly higher among adolescents with vitamin D deficiency. Insulin resistance has also been reported in children and adolescents with vertically transmitted HIV infection in association with higher body mass index values[31,32].

HIV-associated lipodystrophy is a particular cause of concern in adolescence, as the disordered distribution of the body fat - loss of fat in the face and lower limbs and enlarged dorsocervical fat pad and chest fat - might have significant repercussions in this stage of life, when the individual develops the adult body that serves to present oneself to the world. Multidisciplinary healthcare staff should be aware of the possibility that lipodystrophy may act as a hindrance to ART adherence[8].

In addition to the aforementioned body changes, ART is also associated with increased cholesterol and triglyceride levels[33], which make dietary and exercise advice indispensable in the clinical management of these patients[8]. Adolescents at high risk for atherosclerotic disease might benefit from early changes in their lifestyle, as well as from clinical interventions that aim to improve their long-term prognosis[34].

Routine and systematic cardiac evaluation has paramount importance in the follow-up of HIV-infected children and adolescents, as cardiovascular disease has become a part of care for long-term survivors. Accelerated atherosclerosis has also been found in young adults without traditional coronary risk factors[35].

Neuroimaging data collected from healthy children and adolescents show that the brain volume attains its peak by 10.5 years of age among girls and 14.5 years among boys; the grey matter decreases and the white matter increases during adolescence[36]. This developmental stage is known as “synaptic pruning”. The increase in white matter reflects greater axon myelination, with increased neural transmission speed and better quality of brain connectivity.

Some evidence indicates that structural and functional changes in different brain areas are associated with greater rational and emotional planning skills (prefrontal cortex), higher memory capacity (temporal lobe), language skills (frontal lobe), higher intelligence quotient (frontal and occipital lobes), and better reading skills (temporal and parietal lobes). The central executive function processes in this developmental stage include working memory, processing speed, and cognitive flexibility.

One study assessed 16 PHIV adolescents undergoing ART using neuroimaging methods and found increased grey matter and decreased white matter relative to healthy controls[37]. Those findings agree with well-documented alterations in subcortical structures among HIV-infected adults, such as neural loss across the entire prefrontal cortex, cerebral atrophy, and white matter demyelination affecting periventricular areas, the corpus callosum, internal capsule, anterior commissure, and optical tract in particular. The cognitive domains most affected among HIV-infected adults are motor skills, expressive language, episodic memory (encoding and retrieval), and executive function (processing speed, attention, and working memory), the latter of which seems to contribute substantially to learning, particularly during childhood[38-40]. Prospective memory, which is related to “remembering to remember”, is also impaired; this impairment has a close relationship with the action of taking medicine at the right time and, thus, with adherence to treatment. Therefore, the brain and cognitive development of adolescents living with HIV may be impaired in different ways, resulting in lower intelligence and poorer academic performance, executive deficits (abstraction, problem-solving, cognitive flexibility, and cognitive deficits in social skills and planning), limited memory skills, language deficits (in cases with encephalopathy), reduced information processing speed, attention deficit, and impaired motor coordination[41,42].

The results of a literature review on the neurodevelopment of PHIV children and adolescents suggest that such youths do not perform as well as controls in evaluations of cognition, processing speed and visual-spatial tasks and are at higher risk of mental health problems[43]. One study used a neuropsychological battery to assess the cognitive domains of attention/processing speed, psychomotor ability, and problem-solving skills in 16 PHIV adolescents. The results showed that the performance of the PHIV youths was poorer compared to the control group, which consisted of age-matched HIV-uninfected volunteers[44].

In regard to mental health, the incidence of psychiatric disorders is higher among PHIV adolescents and uninfected youths belonging to HIV-infected families compared to the general population[45-47]. Several studies found that up to 70% of such adolescents meet psychiatric diagnostic criteria. Some authors found correlations between diagnosis in adolescents and psychiatric disorders among their caretakers[45-47].

PHIV adolescents start their sexual life at approximately the same age as the HIV-uninfected population[48,49]. Studies on pregnancy showed that its progression and outcomes are similar among PHIV women and women with sexually transmitted HIV, except for the proportion of women with undetectable viral load close to labor and delivery, which is lower among PHIV women[50-52]. The difficulty of attaining viral suppression in that population of pregnant women is probably due to their long previous exposure to various ART regimens, with the consequent emergence of resistance-related mutations in HIV; that fact also accounts for the high rate of cesarean deliveries in that group.

Currently, few ART-naive PHIV adolescents are admitted for treatment. The ongoing strategy of diagnosing women living with HIV during pregnancy allows the early diagnosis of perinatal infection among the exposed infants, while global guidelines emphasize the relevance of starting treatment within the first months of life[53,54]. However, difficulties in adherence to treatment throughout childhood account for the emergence of resistance-associated mutations in the virus, as well as successive drug changes.

When the hindrances to adequate adherence to treatment during childhood are not removed, PHIV adolescents might not achieve appropriate viral suppression and often exhibit multidrug resistance-associated mutations[55]. Several studies have shown that the proportion of PHIV adolescents with viral suppression is approximately 50%[56-59].

The possible transmission of virus strains with resistance-associated mutations by this population to their sexual partners is a significant cause of concern. A longitudinal study that followed up 330 PHIV adolescents who responded to audio computer-assisted self-interviews (ACASI) in the United States found that 62% of the sexually active youths reported engaging in unprotected sexual intercourse. The viral load was over 5000 copies/mL in 42% of the sexually active PHIV adolescents, and in almost all, the virus exhibited resistance-associated mutations[49].

The advances made in AIDS treatment have significantly improved the survival of children and adolescents with vertically transmitted HIV infections[60]. The demand for transfer to adult outpatient care increased concordantly with the extent to which such youths now reach adulthood. More than 25000 HIV-infected individuals aged 13-24 years old are currently undergoing the transition to adult outpatient care in the United States[61].

For this transition to be successful, the focus must fall on comprehensive care, including the patients’ mental and reproductive health, gender identity, sexuality, stigmas, social issues, cognitive development, adherence to ART, detachment from pediatric outpatient care, and communication with the staff in charge of patient care[61-63]. Integral care poses a major challenge; however, it is crucial for the management of this population of patients to reduce the impact of the transition and improve their long-term follow-up. Integral care is necessary to ensure that the therapeutic success achieved in childhood will continue during adulthood[60,62,64].

The aim of this review is to provide information to the pediatricians and infectious disease specialists in charge of continuing the treatment given to PHIV adolescents since childhood. The clinical and laboratory monitoring of these youths should be able to detect problems such as delayed growth and physical and neuropsychological development, metabolic and bone disorders, and issues related to their reproductive health. Possible therapeutic failures should be addressed, considering the individual and family history relative to ART. The follow up of adults perinatally infected with HIV will pose new challenges vis-à-vis the benefits and complications of ART.

Authors thank Dr. Mariza Curto Saavedra Gaspar and Ivete Martins Gomes for text review and suggestions.

| 1. | World Health Organization. Maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health. Adolescent development. [cited 2014 Nov]. Available from: http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/adolescence/dev/en/. |

| 2. | Rassial JJ. O adolescente e o psicanalista. Jorge Nazar editor. : Rio de Janeiro - Companhia de Freud 1999; . |

| 3. | Aberastury A. Adolescência Normal. : Porto Alegre, Artes Médicas 1991; . |

| 4. | Assumpção Jr FB. Adolescência normal e patológica. São Paulo: Lemos Editorial 1998; . |

| 5. | Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2013. [cited 2014 Nov]. Available from: www.unaids.org/Global report 2013. |

| 6. | Agwu AL, Fairlie L. Antiretroviral treatment, management challenges and outcomes in perinatally HIV-infected adolescents. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Manual de Boas Práticas de Adesão. HIV/AIDS, Sociedade Brasileira de Infectologia. . |

| 8. | Brasil , Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de DST, Aids e Hepatites Virais. Recomendações para a Atenção Integral a Adolescentes e Jovens Vivendo com HIV/Aids/Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde, Departamento de DST, Aids e Hepatites Virais. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde 2013; 116. |

| 9. | Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch Dis Child. 1969;44:291-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3911] [Cited by in RCA: 4092] [Article Influence: 71.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in the pattern of pubertal changes in boys. Arch Dis Child. 1970;45:13-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3314] [Cited by in RCA: 3458] [Article Influence: 61.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mahoney EM, Donfield SM, Howard C, Kaufman F, Gertner JM. HIV-associated immune dysfunction and delayed pubertal development in a cohort of young hemophiliacs. Hemophilia Growth and Development Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;21:333-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | de Martino M, Tovo PA, Galli L, Gabiano C, Chiarelli F, Zappa M, Gattinara GC, Bassetti D, Giacomet V, Chiappini E. Puberty in perinatal HIV-1 infection: a multicentre longitudinal study of 212 children. AIDS. 2001;15:1527-1534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Williams PL, Abzug MJ, Jacobson DL, Wang J, Van Dyke RB, Hazra R, Patel K, Dimeglio LA, McFarland EJ, Silio M. Pubertal onset in children with perinatal HIV infection in the era of combination antiretroviral treatment. AIDS. 2013;27:1959-1970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Arpadi SM. Growth failure in children with HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;25 Suppl 1:S37-S42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chantry CJ, Byrd RS, Englund JA, Baker CJ, McKinney RE. Growth, survival and viral load in symptomatic childhood human immunodeficiency virus infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:1033-1039. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Mangili A, Murman DH, Zampini AM, Wanke CA. Nutrition and HIV infection: review of weight loss and wasting in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy from the nutrition for healthy living cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:836-842. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Verweel G, van Rossum AM, Hartwig NG, Wolfs TF, Scherpbier HJ, de Groot R. Treatment with highly active antiretroviral therapy in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected children is associated with a sustained effect on growth. Pediatrics. 2002;109:E25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Brettler DB, Forsberg A, Bolivar E, Brewster F, Sullivan J. Growth failure as a prognostic indicator for progression to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in children with hemophilia. J Pediatr. 1990;117:584-588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Miller TL, Easley KA, Zhang W, Orav EJ, Bier DM, Luder E, Ting A, Shearer WT, Vargas JH, Lipshultz SE. Maternal and infant factors associated with failure to thrive in children with vertically transmitted human immunodeficiency virus-1 infection: the prospective, P2C2 human immunodeficiency virus multicenter study. Pediatrics. 2001;108:1287-1296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Stagi S, Galli L, Cecchi C, Chiappini E, Losi S, Gattinara CG, Gabiano C, Tovo PA, Bernardi S, Chiarelli F. Final height in patients perinatally infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Horm Res Paediatr. 2010;74:165-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Loud KJ, Gordon CM. Adolescent bone health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:1026-1032. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Faulkner RA, Davison KS, Bailey DA, Mirwald RL, Baxter-Jones AD. Size-corrected BMD decreases during peak linear growth: implications for fracture incidence during adolescence. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:1864-1870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bailey DA, Martin AD, McKay HA, Whiting S, Mirwald R. Calcium accretion in girls and boys during puberty: a longitudinal analysis. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:2245-2250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 285] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Puthanakit T, Siberry GK. Bone health in children and adolescents with perinatal HIV infection. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | DiMeglio LA, Wang J, Siberry GK, Miller TL, Geffner ME, Hazra R, Borkowsky W, Chen JS, Dooley L, Patel K. Bone mineral density in children and adolescents with perinatal HIV infection. AIDS. 2013;27:211-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Puthanakit T, Saksawad R, Bunupuradah T, Wittawatmongkol O, Chuanjaroen T, Ubolyam S, Chaiwatanarat T, Nakavachara P, Maleesatharn A, Chokephaibulkit K. Prevalence and risk factors of low bone mineral density among perinatally HIV-infected Thai adolescents receiving antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61:477-483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Barlow-Mosha L, Eckard AR, McComsey GA, Musoke PM. Metabolic complications and treatment of perinatally HIV-infected children and adolescents. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | da Saúde M. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Programa Nacional de DST e AIDS. Recomendações para terapia antirretroviral em crianças e adolescentes infectados pelo HIV. Suplemento I. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2011; 77. [cited 2014 Nov] Available from: www.aids.gov.br. |

| 29. | Lipshultz SE, Williams PL, Wilkinson JD, Leister EC, Van Dyke RB, Shearer WT, Rich KC, Hazra R, Kaltman JR, Jacobson DL. Cardiac status of children infected with human immunodeficiency virus who are receiving long-term combination antiretroviral therapy: results from the Adolescent Master Protocol of the Multicenter Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:520-527. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Chokephaibulkit K, Saksawad R, Bunupuradah T, Rungmaitree S, Phongsamart W, Lapphra K, Maleesatharn A, Puthanakit T. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among perinatally HIV-infected Thai adolescents receiving antiretroviral therapy. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32:1237-1239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Geffner ME, Patel K, Miller TL, Hazra R, Silio M, Van Dyke RB, Borkowsky W, Worrell C, DiMeglio LA, Jacobson DL. Factors associated with insulin resistance among children and adolescents perinatally infected with HIV-1 in the pediatric HIV/AIDS cohort study. Horm Res Paediatr. 2011;76:386-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Dimock D, Thomas V, Cushing A, Purdy JB, Worrell C, Kopp JB, Hazra R, Hadigan C. Longitudinal assessment of metabolic abnormalities in adolescents and young adults with HIV-infection acquired perinatally or in early childhood. Metabolism. 2011;60:874-880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Farley J, Gona P, Crain M, Cervia J, Oleske J, Seage G, Lindsey J. Prevalence of elevated cholesterol and associated risk factors among perinatally HIV-infected children (4-19 years old) in Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group 219C. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;38:480-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Patel K, Wang J, Jacobson DL, Lipshultz SE, Landy DC, Geffner ME, Dimeglio LA, Seage GR, Williams PL, Van Dyke RB. Aggregate risk of cardiovascular disease among adolescents perinatally infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Circulation. 2014;129:1204-1212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Lipshultz SE, Miller TL, Wilkinson JD, Scott GB, Somarriba G, Cochran TR, Fisher SD. Cardiac effects in perinatally HIV-infected and HIV-exposed but uninfected children and adolescents: a view from the United States of America. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Giedd JN. The teen brain: insights from neuroimaging. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42:335-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 520] [Cited by in RCA: 441] [Article Influence: 24.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Sarma MK, Nagarajan R, Keller MA, Kumar R, Nielsen-Saines K, Michalik DE, Deville J, Church JA, Thomas MA. Regional brain gray and white matter changes in perinatally HIV-infected adolescents. Neuroimage Clin. 2014;4:29-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Blanchette N, Smith ML, King S, Fernandes-Penney A, Read S. Cognitive development in school-age children with vertically transmitted HIV infection. Dev Neuropsychol. 2002;21:223-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Nicolau CN. Tese de dissertação Avaliação Neuropsicológica em Crianças e Adolescentes com infecção por HIV e AIDS. : Belo Horizonte 2009; . |

| 41. | Burgess PW, Quayle A, Frith CD. Brain regions involved in prospective memory as determined by positron emission tomography. Neuropsychologia. 2001;39:545-555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 360] [Cited by in RCA: 371] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Okuda J, Fujii T, Yamadori A, Kawashima R, Tsukiura T, Fukatsu R, Suzuki K, Ito M, Fukuda H. Participation of the prefrontal cortices in prospective memory: evidence from a PET study in humans. Neurosci Lett. 1998;253:127-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Laughton B, Cornell M, Boivin M, Van Rie A. Neurodevelopment in perinatally HIV-infected children: a concern for adolescence. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Nagarajan R, Sarma MK, Thomas MA, Chang L, Natha U, Wright M, Hayes J, Nielsen-Saines K, Michalik DE, Deville J. Neuropsychological function and cerebral metabolites in HIV-infected youth. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2012;7:981-990. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Malee KM, Tassiopoulos K, Huo Y, Siberry G, Williams PL, Hazra R, Smith RA, Allison SM, Garvie PA, Kammerer B. Mental health functioning among children and adolescents with perinatal HIV infection and perinatal HIV exposure. AIDS Care. 2011;23:1533-1544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Mellins CA, Elkington KS, Leu CS, Santamaria EK, Dolezal C, Wiznia A, Bamji M, Mckay MM, Abrams EJ. Prevalence and change in psychiatric disorders among perinatally HIV-infected and HIV-exposed youth. AIDS Care. 2012;24:953-962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Gadow KD, Angelidou K, Chernoff M, Williams PL, Heston J, Hodge J, Nachman S. Longitudinal study of emerging mental health concerns in youth perinatally infected with HIV and peer comparisons. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2012;33:456-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Cruz ML, Cardoso CA, João EC, Gomes IM, Abreu TF, Oliveira RH, Machado ES, Dias IR, Rubini NM, Succi RM. Pregnancy in HIV vertically infected adolescents and young women: a new generation of HIV-exposed infants. AIDS. 2010;24:2727-2731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Tassiopoulos K, Moscicki AB, Mellins C, Kacanek D, Malee K, Allison S, Hazra R, Siberry GK, Smith R, Paul M. Sexual risk behavior among youth with perinatal HIV infection in the United States: predictors and implications for intervention development. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:283-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Thorne C, Townsend CL, Peckham CS, Newell ML, Tookey PA. Pregnancies in young women with vertically acquired HIV infection in Europe. AIDS. 2007;21:2552-2556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Badell ML, Kachikis A, Haddad LB, Nguyen ML, Lindsay M. Comparison of pregnancies between perinatally and sexually HIV-infected women: an observational study at an urban hospital. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2013:301763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Calitri C, Gabiano C, Galli L, Chiappini E, Giaquinto C, Buffolano W, Genovese O, Esposito S, Bernardi S, De Martino M. The second generation of HIV-1 vertically exposed infants: a case series from the Italian Register for paediatric HIV infection. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Brasil , Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Programa Nacional de DST e AIDS. Protocolo clínico e diretrizes terapêuticas para manejo da infecção pelo HIV em crianças e adolescentes. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2014; 240. [cited 2014 Nov] Available from: www.aids.gov.br. |

| 54. | AIDSinfo. A Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Pediatric HIV Infection. 316p. [cited 2014 Nov]. Available from: http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/pediatricguidelines.pdf. |

| 55. | Foster C, Judd A, Tookey P, Tudor-Williams G, Dunn D, Shingadia D, Butler K, Sharland M, Gibb D, Lyall H. Young people in the United Kingdom and Ireland with perinatally acquired HIV: the pediatric legacy for adult services. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23:159-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Nachega JB, Hislop M, Nguyen H, Dowdy DW, Chaisson RE, Regensberg L, Cotton M, Maartens G. Antiretroviral therapy adherence, virologic and immunologic outcomes in adolescents compared with adults in southern Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51:65-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 347] [Cited by in RCA: 349] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Dollfus C, Le Chenadec J, Faye A, Blanche S, Briand N, Rouzioux C, Warszawski J. Long-term outcomes in adolescents perinatally infected with HIV-1 and followed up since birth in the French perinatal cohort (EPF/ANRS CO10). Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:214-224. [PubMed] |

| 58. | Santos Cruz ML, Freimanis Hance L, Korelitz J, Aguilar A, Byrne J, Serchuck LK, Hazra R, Worrell C. Characteristics of HIV infected adolescents in Latin America: results from the NISDI pediatric study. J Trop Pediatr. 2011;57:165-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Cruz ML, Cardoso CA, Darmont MQ, Souza E, Andrade SD, D’Al Fabbro MM, Fonseca R, Bellido JG, Monteiro SS, Bastos FI. Viral suppression and adherence among HIV-infected children and adolescents on antiretroviral therapy: results of a multicenter study. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2009;90:563-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Fair CD, Sullivan K, Dizney R, Stackpole A. “It’s like losing a part of my family”: transition expectations of adolescents living with perinatally acquired HIV and their guardians. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012;26:423-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 61. | Cervia JS. Easing the transition of HIV-infected adolescents to adult care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2013;27:692-696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Ross AC, Camacho-Gonzalez A, Henderson S, Abanyie F, Chakraborty R. The HIV-Infected Adolescent. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2010;12:63-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Hazra R, Siberry GK, Mofenson LM. Growing up with HIV: children, adolescents, and young adults with perinatally acquired HIV infection. Annu Rev Med. 2010;61:169-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Mofenson LM, Cotton MF. The challenges of success: adolescents with perinatal HIV infection. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewer: Berardinis PD, Kamal SA, Margulies BJ S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Yan JL

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/