Published online Sep 25, 2024. doi: 10.5501/wjv.v13.i3.92525

Revised: May 20, 2024

Accepted: July 4, 2024

Published online: September 25, 2024

Processing time: 213 Days and 2.6 Hours

Varicella (chickenpox) and herpes zoster (shingles) are outcomes of varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infection, and understanding their incidence trends is vital for public health planning.

To conduct an ambispective epidemiological study by analyzing the main epidemiological characteristics of VZV infection during an 18 year-period (2000-2018).

We used descriptive and epidemiological methods to characterize chickenpox in Bulgaria, the city of Plovdiv and the region for a period of 18 years (2000-2018).

The average incidence of varicella-zoster infection for the period 2000–2018 in the Plovdiv region was estimated at 449.58‰. The highest relative share of the infection was assessed in the month of January at 13.6%, and the lowest in the months of August and September at 2.9% (both months). The age group most affected by the infection was 1-4 years, followed by 5-9 years. This corresponds to the so-called "pro-epidemic population" - a phenomenon typical for airborne infections, confirming their mass impact on the perpetuation of VZV infection.

Our findings reveal significant insights into VZV epidemiology, including age-specific incidence rates, clinical manifestations, and vaccination impact. This comprehensive analysis contributes to the broader understanding of VZV infec

Core Tip: This ambispective epidemiological study shows an 18-year exploration of Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infection dynamics in Bulgaria's Plovdiv region. With varicella (chickenpox) and herpes zoster (shingles) as VZV outcomes, our findings expose a noteworthy average incidence of 449.58 per 100000 from 2000 to 2018. Notably, January peaked at 13.6%, while August and September hospitalizations were the lowest at 2.9%. The age groups most impacted, 1-4 and 5-9 years, align with the 'population pro-epidemic' concept. These outcomes demonstrated crucial insights into VZV epidemiology, guiding evidence-based preventive measures and contributing significantly to public health planning.

- Citation: Batselova HM, Velikova TV. Ambispective epidemiological observational study of varicella-zoster virus infection: An 18 year-single-center Bulgarian experience. World J Virol 2024; 13(3): 92525

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3249/full/v13/i3/92525.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5501/wjv.v13.i3.92525

Varicella is an acute, highly contagious infectious disease caused by the varicella-zoster virus (VZV), with an acute onset, usually elevated temperature, a moderately impaired general condition and a cyclically developing pseudopolymorphic rash accompanied by itching (i.e., macules, papules, vesicles, crusts)[1-3].

Years later, VZV may reactivate and cause various neurologic conditions, such as herpes zoster, postherpetic neuralgia, vasculopathy, myelopathy, retinal necrosis, cerebellitis, and zoster sine herpete. This reactivation is linked to a decline in cell-mediated immunity, typically seen in elderly and immunocompromised people. Usually, herpes zoster is a late reactivated infection characterized by a painful, dermatome-unilaterally located herpetiform rash[4,5]. It is generally associated with a reactivation of VZV after experiencing chickenpox in childhood.

In the absence of a vaccine against varicella, the number of patients each year is equal to the cohort of newborns, with 52%-78% of cases being children under 6 years of age and 89%-95% aged less than 12[3]. In different regions of the world, varicella occurs with a clear seasonality: morbidity of VZV is highest in winter and early spring[2,6].

The VZV is widespread in Europe, and in most countries the infection usually occurs between the ages of 2 and 10 years. However, in some countries, antibodies are detected at an earlier age than in other European countries. Most newborns are seropositive for VZV due to naturally acquired passive immunity from the mother during pregnancy[7].

Chickenpox is an anthroponosis. The only source of infection is contact with a person infected with chickenpox or herpes zoster[8]. The varicella virus enters the epithelial cells of the mucous membrane of the upper respiratory tract and the conjunctiva by an airborne mechanism. Therefore, entry is by the mucous membranes of the upper respiratory tract and the conjunctivae[9].

The epidemiological observational study of VZV infection holds significant importance in public health and clinical practice. Understanding the dynamics of VZV infection, including age-specific incidence rates, clinical manifestations, and vaccination impact, provides crucial insights into disease prevention and control strategies. By elucidating the epidemiological trends and risk factors associated with VZV infection, healthcare professionals and policymakers can implement targeted interventions such as vaccination campaigns and public health policies to mitigate the burden of VZV-related diseases. Therefore, conducting comprehensive epidemiological studies on VZV infection is paramount for enhancing our understanding of the disease's impact and improving preventive measures.

We aimed to retrospectively analyze the main epidemiological characteristics of VZV infection from 2000 to 2018. Specifically, we estimated the age-specific incidence rates of VZV infection, examined the clinical manifestations and complications associated with VZV, investigated the impact of VZV vaccination programs on disease prevalence, and identified any temporal trends or shifts in VZV epidemiology over the 18-year study period. By comprehensively analyzing these epidemiological aspects, we aim to contribute valuable insights to inform public health strategies, guide clinical management practices, and reduce the burden of VZV-related diseases within our population.

Characterization of chickenpox in Bulgaria, the city of Plovdiv, and the region for 18 years (2000-2018) was carried out.

We extended our investigation to all-day kindergartens "Detstvo moe" and "Raya" (2018-2019) and the Clinic for Infectious Diseases at "St. George UMBAL" (935 patients were studied during the period 2008-2018). Of these patients, 336 were studied prospectively from 2012 to 2018. Additionally, the Regional dispensary for skin-venereal diseases in Plovdiv (2006-2009) was included in our analysis. We also evaluated the following: patients with established varicella zoster infection – 1104 people; patients with chickenpox in children's institutions - 107 children; hospitalized patients diagnosed with chickenpox - 935 patients; and patients hospitalized for herpes zoster - 165 patients.

We used a descriptive method to assess the real epidemic situation during the specified period and an epidemiological retrospective analysis to search for dependencies and cause-and-effect relationships and characterize chickenpox in Bulgaria, the city of Plovdiv and the region.

The obtained data were entered and processed with the statistical package IBM SPSS Statistics 25.0. MedCalc Version 19.6.3., as well as Office Excel 2021 were also used. P < 0.05 was accepted as a level of significance at which the null hypothesis is rejected.

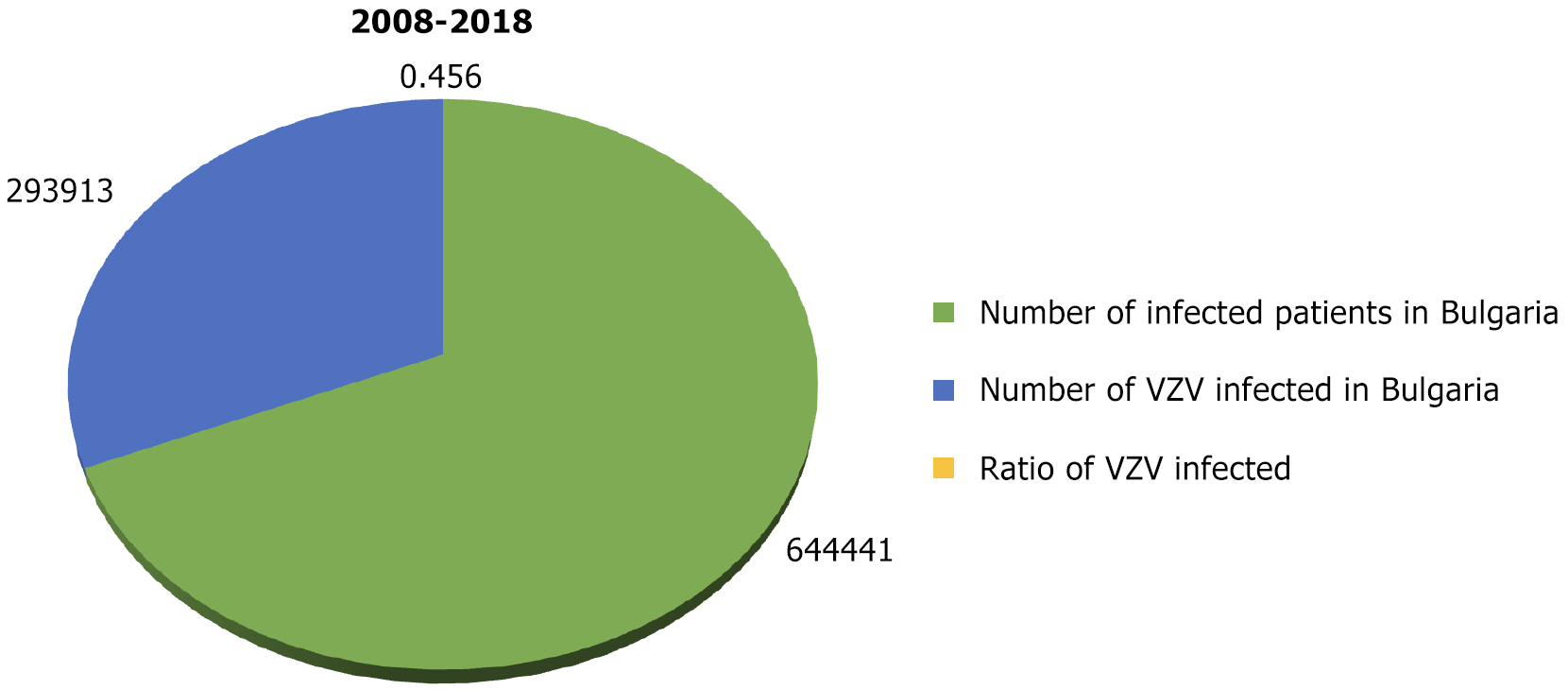

According to data from the National Institute of Health and Welfare (National Center for Infectious and Parasitic Diseases)[10], for the 11 years from 2008 to 2018 in Bulgaria, 293913 people had chickenpox. The average annual morbidity was 365.52‰. During the same period, there were 644441 people in the country with infectious diseases (excluding influenza and acute respiratory infections). The relative share of chickenpox cases was 45.6% (Figure 1).

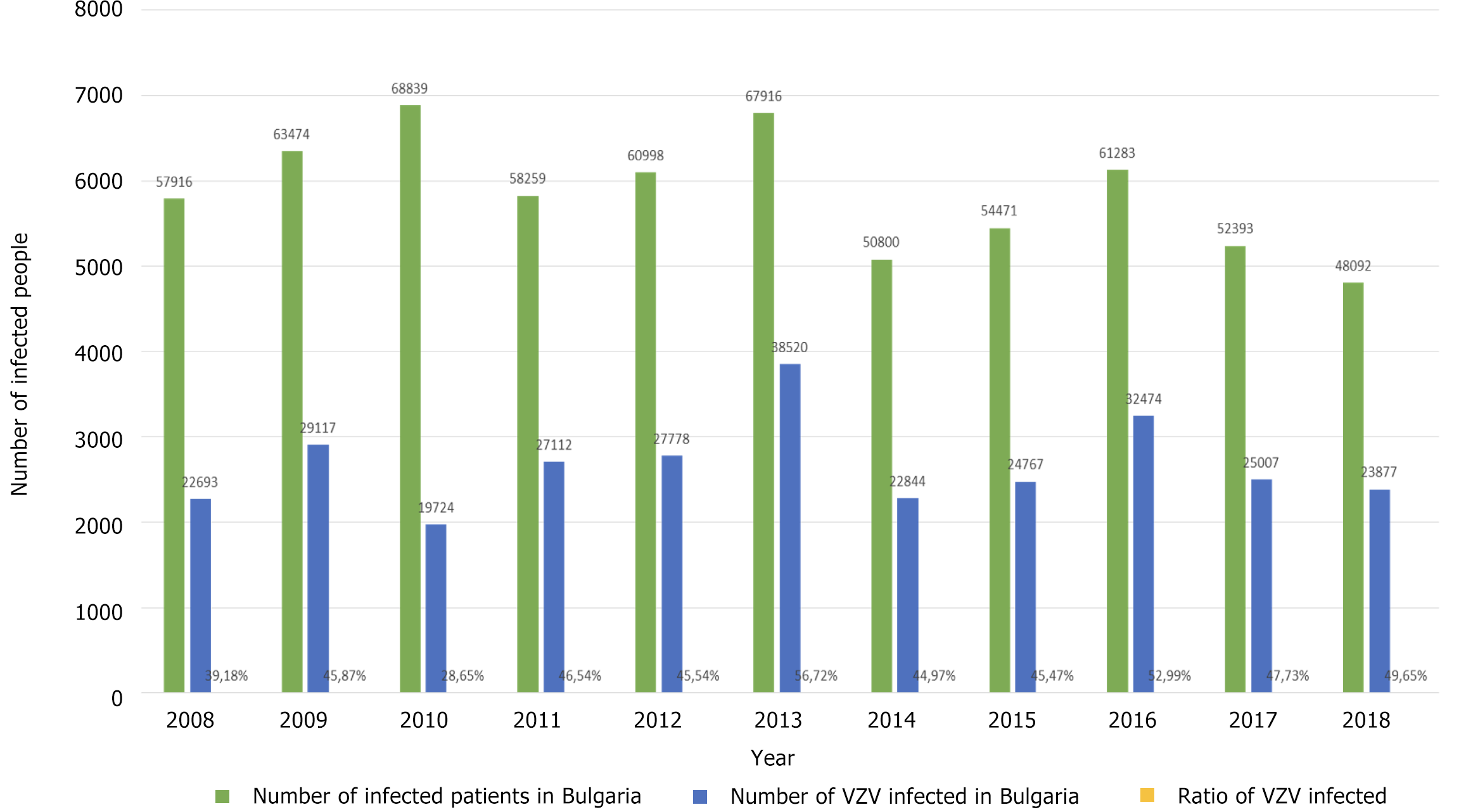

The highest relative share of chickenpox patients was observed in 2013 at 56.72% and the lowest in 2010 at 28.65%, during which period a measles epidemic also occurred. Figure 2 shows the relative share of patients with chickenpox (out of the total number of infectious patients) during 2008-2018. It was estimated below 40% in 2008 and 2010 alone (39.18% and 28.65%, respectively). In the remaining 8 years, the relative share varied from 44.97% to 56.72%.

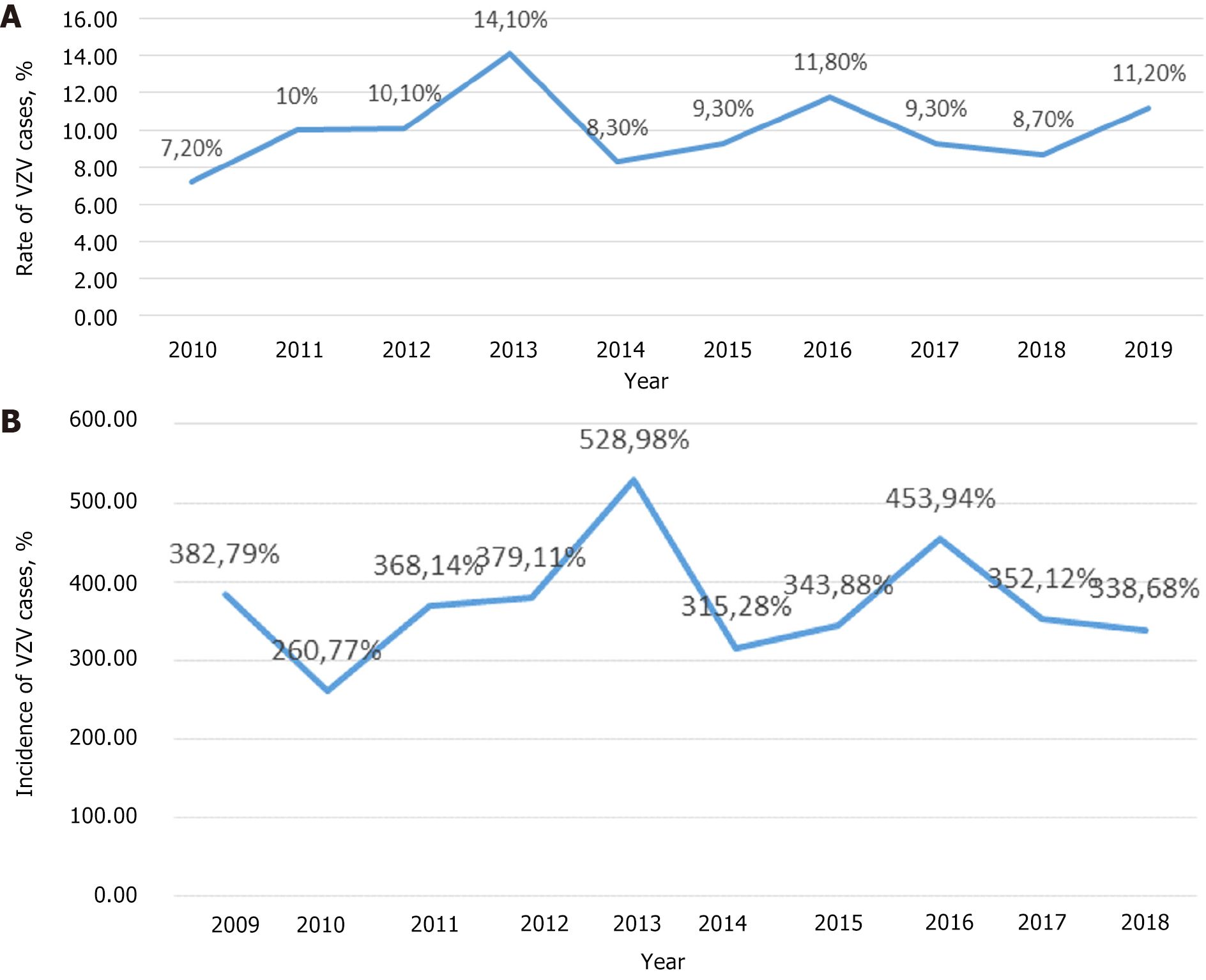

In Figure 3A, the distribution of VZV infection cases by year is shown, and in Figure 3B, the incidence of chickenpox in Bulgaria is shown. The highest rate was in 2013 - 528.98‰ and the lowest in 2010 - 260.77‰.

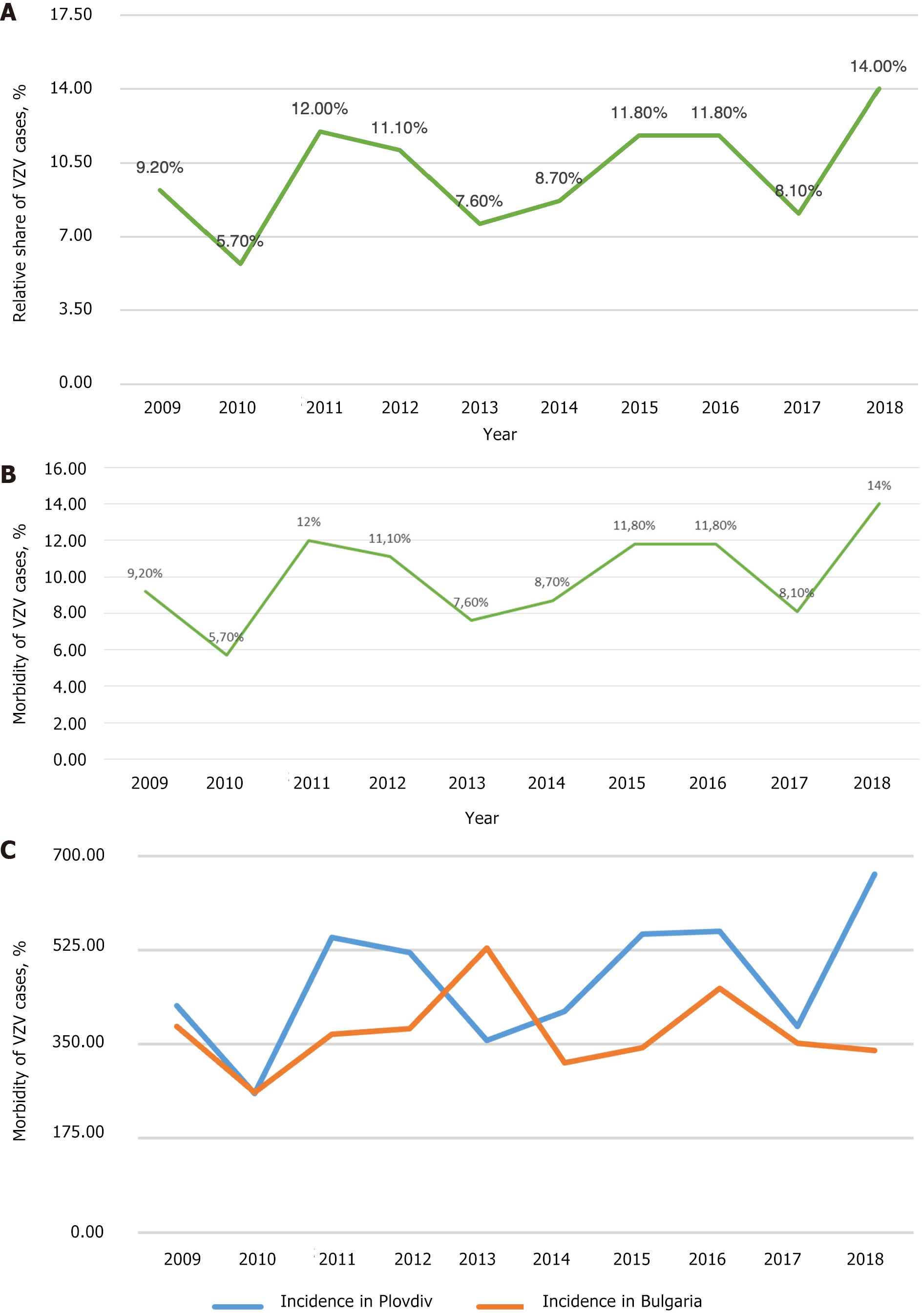

According to the Regional Health Agency of Plovdiv data, 56502 people were registered with chickenpox from 2000 to 2018 in the Plovdiv region (Figure 4A). The average morbidity during the studied period was 449.58‰ (Figure 4B). Notably, in 2010, in the Plovdiv region, the relative share of patients with chickenpox was the lowest compared to the other years (Figure 4C). This corresponds to the lowest relative share for the whole country of Bulgaria in the same year (2010). At that time, the relative share of measles patients in Bulgaria was the highest. During 2000-2018, the incidence of chickenpox in the Plovdiv region was estimated as follows: The lowest in 2002 (220.21‰) and the highest in 2018 (666.20‰). Additionally, in Figure 4C the incidence of chickenpox in the Plovdiv region is compared with that in Bulgaria for 10 years (2009-2018).

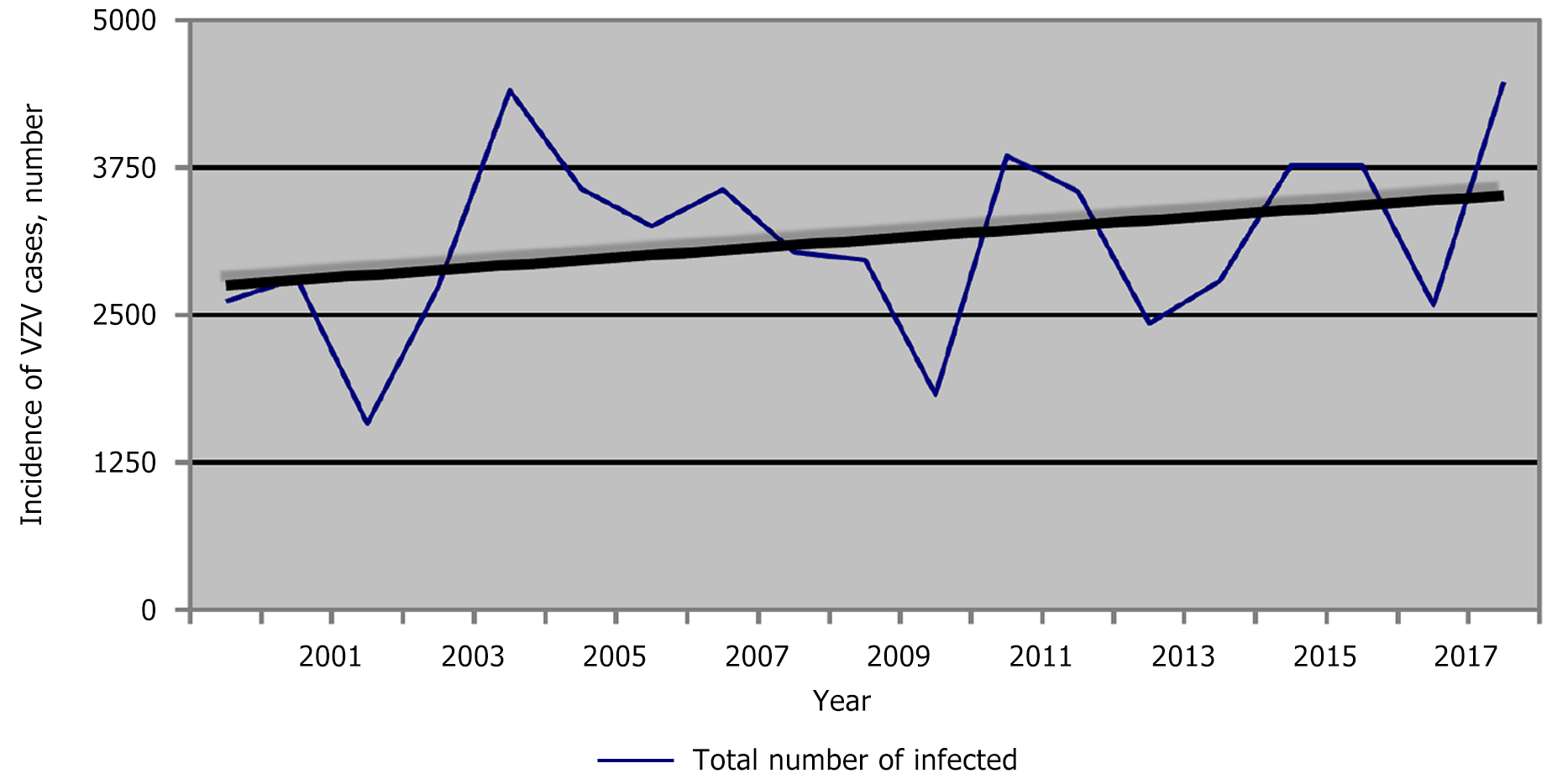

For Bulgaria, the trend profile for chickenpox is stationary, while in Plovdiv, it is slightly progressive (Figure 5). The reasons for this are diverse. According to data from the National Statistical Institute, the largest number of people moving to the country chose the Plovdiv region as their new place of residence, and only for 2021, immigrants totaled 21320 people (https://www.nsi.bg/bg).

On the other hand, the regions of Sofia, Varna and Plovdiv have the lowest coefficient of negative natural growth (from -3.5‰ to -6‰) in contrast to the areas of Vidin and Montana (from -18‰ to -22‰). In this way, the graph for Bulgaria, which is averaged for all regions, remains stationary. In contrast, due to the resettlement factor and the coefficient of natural growth, the graph for the Plovdiv region is slightly progressive.

It is noteworthy that in 2010, the morbidity rate was almost the same. In 2017, similar morbidity was observed again, while in 2018, the difference was considerable. Analysis of the morbidity trend in the Plovdiv region during the studied years (2000-2018) showed an upward trend (the average coefficient of increase in the number of patients was approximately 1.56) (Figure 5).

A statistically significant difference was demonstrated between peaks in incidence across years (P = 0.004) (data not shown visually). The peak average was 4242.00, and for the other years - 2925.19. The study period is relatively short, but the obtained results show that the decline in the incidence always precedes the year with the peak incidence.

We observed three peaks - in 2004, 2011, and 2018, with respective incidences of 618.21‰, 548.11‰ and 666.20‰. As expected, a substantial decline preceded each peak. We also found a cyclicity of the peaks every 7 years.

Our retrospective study showed that the average incidence of varicella-zoster infection from 2000 to 2018 in the Plovdiv region was 449.58‰. For this period, Bulgaria reported a high incidence of chickenpox, and we can speculate that this is due to the absence of mass immunoprophylaxis with the live, attenuated vaccine.

Data from the years studied showed that 2010 had the lowest relative share of chickenpox patients in the Plovdiv region. This corresponds to the data for the country at the time of the measles epidemic. From 2009 to 2018 (i.e., a decade), the curve reflecting the trend of the incidence of varicella-zoster infection in the country was stationary. In the Plovdiv region, it was slightly progressive (average coefficient of increase in the number of patients was 1.56). We can explain these results with the data on internal migration. According to data from the National Statistical Institute in Bulgaria[11], most Bulgarian citizens who move to the country choose the Plovdiv region as their new place of residence. This observation mainly concerns young people with children who are potentially susceptible to the infection. These results are supported by the coefficient of negative natural growth, which for the districts of Sofia, Varna and Plovdiv is the lowest in contrast to the districts of Vidin and Montana. Besides, averaging these values explains the stationary curve of morbidity for the country and the slightly progressive trend of the curve for the Plovdiv region due to the recent population migration and the coefficient of negative natural growth.

Our observations proved peaks of high morbidity of varicella infection – higher and lower, which alternated. This is in accordance with other studies which demonstrated that demographic endemicity is determined by the continuous accumulation of a susceptible population (i.e., newborns) and continuous maintenance of the infection with sporadic cases. Additionally, the cyclicity of the demographic endemicity of varicella shows how sporadic incidence turns into epidemic waves when sufficient susceptible individuals are accumulated in the population, usually every 5 years on average. However, the cycles could be small (every 2-7 years) and large (every 20-22 years)[3].

A statistically significant difference was demonstrated between peaks in incidence across years (P = 0.004) with average peaks of 4242.00‰, and in the remaining years, 2925.19‰. The summarized results of the study demonstrated further that the decline always precedes the year with the peak incidence. The observed three peaks (in 2004, 2011, and 2018, with an incidence of 618.21‰, 548.11‰ and 666.20‰, respectively) and cyclicity of 7-year intervals correspond to the studies of the investigators across different countries mentioned above.

In Bulgaria, chickenpox had a high incidence from 2000 to 2018 due to the absence of mass immunoprophylaxis with the live, attenuated vaccine. The curve reflecting the trend of morbidity in Bulgaria is of a stationary type. The epidemic process in the country and the region shows activation and decline in 7 years (known as "multi-year cyclicity").

| 1. | Mueller NH, Gilden DH, Cohrs RJ, Mahalingam R, Nagel MA. Varicella zoster virus infection: clinical features, molecular pathogenesis of disease, and latency. Neurol Clin. 2008;26:675-697, viii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Order No. 21 of July 18, 2005. On the regulation for registration, communication and reporting of communicable diseases. Available from: https://www.mh.government.bg/media/filer_public/2015/04/17/naredba-21-ot-2005g-spisak-zarazni-bolesti-red-registratsia.pdf. |

| 3. | Varicella vaccination in the European Union. ECDC guidance. Available from: http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/Varicella-Guidance-2015.pdf. |

| 4. | Jones JO, Arvin AM. Inhibition of the NF-kappaB pathway by varicella-zoster virus in vitro and in human epidermal cells in vivo. J Virol. 2006;80:5113-5124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Wutzler P, Casabona G, Cnops J, Akpo EIH, Safadi MAP. Herpes zoster in the context of varicella vaccination - An equation with several variables. Vaccine. 2018;36:7072-7082. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Varela FH, Pinto LA, Scotta MC. Global impact of varicella vaccination programs. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15:645-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Zhang X, Wei M, Sun G, Wang X, Li M, Lin Z, Li Z, Li Y, Fang M, Zhang J, Li S, Xia N, Zhao Q. Real-time stability of a hepatitis E vaccine (Hecolin®) demonstrated with potency assays and multifaceted physicochemical methods. Vaccine. 2016;34:5871-5877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chapter 22: Varicella; Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine. Preventable Dis-eases. CDC. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/downloads/varicella.pdf. |

| 9. | Regulation No. 21 of July 18, 2005 on registration, communication and reporting of communicable diseases effective from January 1, 2006. Issued by the Minister of Health. Available from: https://lex.bg/laws/ldoc/2135508238. |

| 10. | Informing bulletin for VZV infections. National Center for Infectious and Parasitic Diseases. Available from: https://www.ncipd.org/index.php?option=com_biuletin&view=view&month=25&year=2024&lang=bg. |

| 11. | Internal migration of the Bulgarian citizens. National Statistical Institute. Last access on June 25, 2024. Available from: https://www.nsi.bg/bg/content/3067/54-%D0%B2%D1%8A%D1%82%D1%80%D0%B5%D1%88%D0%BD%D0%B0-%D0%BC%D0%B8%D0%B3%D1%80%D0%B0%D1%86%D0%B8%D1%8F-%D0%BD%D0%B0-%D0%BD%D0%B0%D1%81%D0%B5%D0%BB%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%B5%D1%82%D0%BE-%D0%BC%D0%B5%D0%B6%D0%B4%D1%83-%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B0%D1%82%D0%B8%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B8%D1%87%D0%B5%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%B8%D1%82%D0%B5-%D1%80%D0%B0%D0%B9%D0%BE%D0%BD%D0%B8-%D0%BF%D0%BE-%D0%BF%D0%BE%D0%BB. |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/