Published online Sep 25, 2022. doi: 10.5501/wjv.v11.i5.275

Peer-review started: March 18, 2022

First decision: May 12, 2022

Revised: May 20, 2022

Accepted: July 26, 2022

Article in press: July 26, 2022

Published online: September 25, 2022

Processing time: 189 Days and 20.7 Hours

With a 5.3% of the global population involved, hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a major public health challenge requiring an urgent response. After a possible acute phase, the natural history of HBV infection can progress in chronicity. Patients with overt or occult HBV infection can undergo HBV reactivation (HBVr) in course of immunosuppressive treatments that, apart from oncological and hem-atological diseases, are also used in rheumatologic, gastrointestinal, neurological and dermatological settings, as well as to treat severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. The risk of HBV reactivation is related to the immune status of the patient and the baseline HBV infection condition. The aim of the present paper is to investigate the risk of HBVr in those not oncological settings in order to suggest strategies for preventing and treating this occurrence. The main studies about HBVr for patients with occult hepatitis B infection and chronic HBV infection affected by non-oncologic diseases eligible for immunosuppressive treatment have been analyzed. The occurrence of this challenging event can be reduced screening the population eligible for immunosuppressant to assess the best strategies according to any virological status. Further prospective studies are needed to increase data on the risk of HBVr related to newer immunomodulant agents employed in non-oncological setting.

Core Tip: Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) is a major public health challenge requiring an urgent response. Patients with overt or occult HBV infection can undergo HBV reactivation (HBVr) in course of immu-nosuppressive treatments, also used in rheumatologic, gastrointestinal, neurological and dermatological settings and to treat Sars severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. The aim of the present paper is to investigate the risk of HBVr in those not oncological settings in order to suggest strategies for preventing and treating this occurrence. The occurrence of this challenging event can be reduced screening the population eligible for immunosuppressant to assess the best strategies according to any virological status.

- Citation: Spera AM. Hepatitis B virus infection reactivation in patients under immunosuppressive therapies: Pathogenesis, screening, prevention and treatment. World J Virol 2022; 11(5): 275-282

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3249/full/v11/i5/275.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5501/wjv.v11.i5.275

Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) is a major public health challenge requiring an urgent response. According to the Global Hepatitis Report endorsed by World Health Organization (WHO) in 2017, the proportion of children 5 years old become chronically infected felt to 1.3% in 2015, compared with 4.7% of the pre-vaccine era, ranging 1980s to 2000s worldwide[1]. The spread of HBV vaccination during the childhood reduced the incidence of new HBV infections and the related possible chronicity[1]. However, it is estimated that about 3.5% of the global population (257 million people) in 2015 are affected by chronic HBV infection, most of them born before the availability of HBV vaccination: 68% of them are localized in Africa and in Western Pacific Region[1]. About 2.7 million of persons are co-infected with HBV, HDV and HIV and, among those with hepatitis, the estimated cumulative 5 years incidence of progression is estimated around 8%-20%[2] and 5%-15% of cirrhotic patients develop hepatocellular cancer (HCC) during the lifetime[2].

HBV belongs to the Hepadnaviridae family. It is a double stranded DNA virus with a lipoprotein envelope and a high hepatic tropism. Its transmission happens through the vertical route or intra-family contacts among infants and by sexual or parenteral contact. The first case is typical in regions with the highest prevalence determining the high endemicity described in these areas and the associated high rate of chronicization. The second case is common in regions with low prevalence among adults; ne-vertheless, high Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) prevalence there, can be encountered among immigrants from high HBV endemic area, People Who Inject Drugs (PWID), Men who have Sex with Men and People Living With HIV[3]. After a possible acute phase, the natural history of HBV infection can progress in chronicity, which consists of 5 phases, based on the HBeAg serostatus, the viral load, the transaminases levels and the grading/staging of the liver disease[4-6]. During the first one, once known as “immunotollerant phase” and currently named “HBeAg positive chronic infection”, the immune response against the virus is limited or absent: Thus, there is a high viral replication with HBeAg positivity, unchanged transaminases and liver parenchyma. The second phase, called “HBeAg positive chronic hepatitis” is characterized by the production of active immune response of the host against viral antigens, with a reduction of viral load and an increase of transaminase levels along with liver inflammation. In case of immune response’s control of the infection, the infection moves to the third phase, known as “HBeAg negative chronic infection” with HBeAg sero-clearance, low viral replication (HBV-DNA < 2000 IU/mL), normalization of transaminase levels and mild liver inflammation. However, severe liver inflammation and rapid progression of disease can still occurs, despite the presence of HBeAb, in case of mutation of the pre-core or basal core promoter regions. The fourth phase is the “HBeAg negative chronic hepatitis” one, with detectable anti HBe, moderate levels of serum HBV-DNA and ALT with hepatic necroinflammation. The last phase is HBsAg negative phase, with serum negative HBsAg and positive anti HBc with or without anti HBs. This phase is also called “occult hepatitis B virus infection” (OBI) defined as the replication of competent HBV DNA in the liver and blood in the absence of detectable HBsAg that contributes to the advancement of liver fibrosis and development of HCC. Patients with overt or occult hepatitis B virus infection can undergo HBV reactivation (HBVr) in course of immunosuppressive treatments. Apart from oncological and hematological diseases, immunosuppressants are also used in rheumatologic, gastrointestinal, neurological and dermatological settings, as well as to treat severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection. The aim of the present paper is to investigate the risk of HBVr in those not oncological settings in order to suggest strategies for preventing and treating this occurrence. HBVr can be defined as the novo detection of HBV DNA or a ≥ 10 fold increase in HBV DNA level compared to its baseline value in HBsAg positive subject and seroreversion to HBsAg positive status in previously negative patients[7]. The viral genome can be detected as cccDNA in hepatocites. The HBVr following immunosuppressive treatments is commensurate to patient’s characteristics and the kind of immunosuppressive agent employed. As regards as host characteristics, apart from the male gender[8], the old age[9] and any underlying lymphoproliferative diseases[10], the serostatus during immunosuppression is crucial. In fact, patients affected by chronic HBV infection have a greater risk of reactivation compared to those with OBI. Moreover, the presence of anti HBs among HBsAg negative subjects, is related to a lower risk of reactivation even in hematologic setting, according to Seto et al[11]. Regarding immunosuppressant, the risk of related HBVr can be classified as high, with frequency of reactivation > 10% without pro-phylaxis[7]; medium, with frequency of reactivation 1%-10%[12] or low, with frequency of reactivation < 1%[13]. A high risk of reactivation is described with the administration of B cell depleting agents[14], anthracycline derivatives[15] and corticosteroids at high dose, for treatments of more than 4 wk[7], along with inhibitors of cytokine, integrin[16], tyrosine kinases[17] and JAK kinases inhibitors[18].

The risk of HBVr is related to the immune status of the patient and the baseline HBV infection condition. The risk of developing HBVr is quite low for HBsAg positive or negative patients under csDMARDs and short low dose cortisone based therapy. The same risk is however higher for patients under anti-TNFs and tyrosine kinase inhibitors: when in combination, the risk is the highest.

Here reported are the main studies about HBVr for patients with OBI and chronic HBV infection affected by non-oncologic diseases eligible for immunosuppressive treatment.

The ongoing SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, responsible for more than 50 million cases from 2020, still represents a challenge for the scientific community, not only regarding its pathogenesis but mostly its treatment. In fact, despite there is no available curative option yet, several immunosuppressive and immunomodulating agents have been proposed for the treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia in those last two years. Corticosteroids are currently recommended by the WHO for severe COVID-19; other employed immunosuppressive agents are interleukin 6 inhibitors (such as tocilizumab), JAK inhibitors (such as baricitinib, tofacitinib and ruxolitinib) associated with risk of HBVr in other settings[19]. Apart from a couple of retrospective studies reporting HBVr among patients receiving methylprednisolone[20] and tocilizumab[21], no data are already available in literature about the risk of HBVr among patients with COVID-19 treated with immunosuppressants. The short duration of immunosuppressive treatment in this specific setting probably limits the risk of HBVr. However, all the patients with COVID-19 pneumonia eligible for corticosteroid or immunosuppressants are routinely screened for HBV infection according to national and international guidelines to evaluate the risk of HBVr prior to prescribe those above mentioned drugs and start antiviral prophylaxis when needed.

The spread of rheumatic diseases in Western Countries resulted in a greater interest of the scientific community engaged in research of efficacious therapeutic options. Giving that recognize an autoimmune pathogenesis, therapeutic committed strategies are based on immunosuppression and include Corticosteroids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), analgesic drugs and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) which can be divided into conventional synthetics (csDMARDs) and biological drugs (bDMARDs). The csDMARDs include leflunomide, azathioprine, sulfasalazine, hydroxychloroquine; gold salts, methotrexate and minocycline[22]. The bDMARDs can be instead divided into IL-1 inhibitors (canakinumab and anakinra), TNF inhibitors (infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept, certolizumab and golimumab), inhibitors of IL-17 (ixekizumab and secu-kinumab), IL-6 and IL-6R inhibitors (respectively, tocilizumab and sarilumab), IL-23 inhibitors (guselkumab and ustekinumab), and JAK kinase inhibitors (peficitinib, tofacitinib, filgotinib, upadacitinib and baricitinib) based on their mechanism of action[23,24].

HBVr is quite common among unvaccinated people with rheumatic diseases (RD); Canzoni et al[25] reports that 2% of this study population (292 patients) affected by RD had a prevalence of HBsAg positivity and any kind of HBV infection markers retrieved in 24% of cases (70 patients): At least, 30% of those tested positive patients were unaware of their condition[25]. Despite European Association for the Study of Liver (EASL)[4] and AASLD[23] indication about HBV routine screening schedule before starting immunosuppressive therapies, the coverage still appears inadequate as in 2015 Lin et al[27] demonstrated in a retrospective cross national comparison of hepatic testing in rheumatic arthritis (RA) patients eligible to DMARD between the US and Taiwan[26]. The authors found that only 20.3% of patients in the US and 24.5% of patients in Taiwan were tested for HBV infection[27]. Similar results were found in Japan[28] where laboratory test for HBsAg, anti HBs and anti HBc were performed only in 28.33%, 12.52% and 14.63% of patients with RA, at baseline[28]. The deleterious role of HBV infection in recovery of patients with RA has been investigated by Chen et al[29]: Their case control study evaluated 32 patients with RA and chronic HBV infection, eligible to glucocorticosteroids, DMARDs and biologics. The study records, in a year, a worsening of hepatopathy of patients with chronic HBV infection under immunosuppressant with no antiviral intervention; moreover patients failed in achieving the therapeutic target in 6 mo. HBVr was reported in 34% of patients at one year follow up. Among those 32 studied patients, 14 were treated with prophylaxis with lamivudine, adefovir or entecavir: 4 of them developed HBVr and 2 of them also a hepatitis flare. The remaining 18 patients enrolled did not received antiviral prophylaxis and 7 of them experienced HBVr.

cDMARDs such as acitretin, methotrexate and cyclosporin A along with bDMARDs including etanercept, infliximab, golimumab, certolizumab, adalimumab and secukinumab are currently used in several different dermatologic diseases, like psoriasis. The safety of those immunosuppressive drugs is not properly investigated, since trials conceived to explore new efficient drugs barely involve HBV patients. However, the reactivation risk of HBV in 14 (11 HBsAg positive, 3 HBsAg negative/HBcAb positive) patients with psoriasis eligible for ustekinumab based therapy has been evaluated by Chiu et al[30]. No reactivation was observed among all the HBsAg negative HBcAb positive patients, while HBVr was registered among two of the HBsAg positive patients under ustekinumab not receiving prophylaxis[30]. The incidence rate of annual HBVr was calculated by Ting et al[31] in a retrospective cohort study including 54 inactive HBV carrier patients without prophylaxis and occult hepatitis B virus infection: only 1.5% of OBI patients developed HBVr, while 17.4% of inactive HBV carriers experienced it, under ustekinumab. According to the available evidence, HBsAg positive patients under immunosuppressive drugs at moderate risk of HBVr should be prevented with antiviral based prophylaxis, while HBsAg negative/HBcAb positive patients eligible for immunosuppressant should be close monitored in order to prescribe pre-emptive therapy, when needed.

The use of immunosuppressants is often required for patients affected by autoimmune, inflammatory gastroenterological disorders like Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis. The drug selected depends on the disease severity and the relapsing or remitting cause of the inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Corticosteroids, immunomodulatory agents (methotrexate, azathioprine, mercaptopurine), anti IL12/23 p40 antibodies, JAK inhibitors, anti-adhesion therapies and biological therapies such as TNF inhibitors are widely used. Studies performed to evaluate the risk of HBVr in HBsAg positive patients with gastroenteric diseases under immunosuppressive agents clearly demonstrated that the use of more than two immunosuppressive agents is an independent predictor of HBVr[32]. A lower rate of reactivation has been registered for patients treated with antiviral prophylaxis[33]. Few cases of HBVr have been reported among HBsAg negative/HBcAb positive patients with IBD under immunosuppressants[34-37]. Thus, a complete serology for HBV is required in IBD patients to determine the active/inactive carrier status of IBD patients eligible for immunosuppressants in order to determine whether to treat, prescribe prophylaxis or monitor them, according to their HBV profile. HBsAg positive patients with IBD should undergo prophylaxis with nucleotide or nucleoside analogues before starting moderate or high doses steroids for more than 4 wk, anti TNF drugs, azathioprine or ustekinumab. This prophylaxis should last for at least one year after discontinuing immunomodulants. No standardized approach exists for HBsAg negative/HBcAb positive patients with IBD. In fact, while the American Gastroenterology Association recommends antiviral prophylaxis for this population under anti TNF or corticosteroids at moderate/high doses[38], the EASL and The European Crohn and Colitis Organization both recommend close monitoring of this population and the use of antiviral agents only after detection of HBV DNA viremia or seroreversion to HBsAg positivity[4,39].

Among neurodegenerative diseases requiring disease modifying drugs to be treated, multiple sclerosis (MS) is one of the most frequent. MS causes chronic inflammation of the central nervous system, demyelination and disability. Apart from glucocorticoids, widely used in the acute phase of MS, DMD such as anti CD52 antibodies (alemtuzumab), anti CD20, a4b1 integrin inhibitor, sphingosine 1 phosphate inhibitors and its modulators (namely, fingolimod and siponimod), anti CD20 monoclonal antibodies[40] are employed to treat MS. Since limited data concerning the risk of HBVr in neurological setting are available from literature, there is no clear, definitive consensus on the best strategies to prevent HBVr in subjects with neurologic diseases requiring immunosuppressive drugs[41]. However, HBVr in a patient with a story of HBV infection and no proper prohylaxis, under ocrelizumab treatment for MS, has been reported by Ciardi et al[42], highlighting the need for antiviral prophylaxis in this setting.

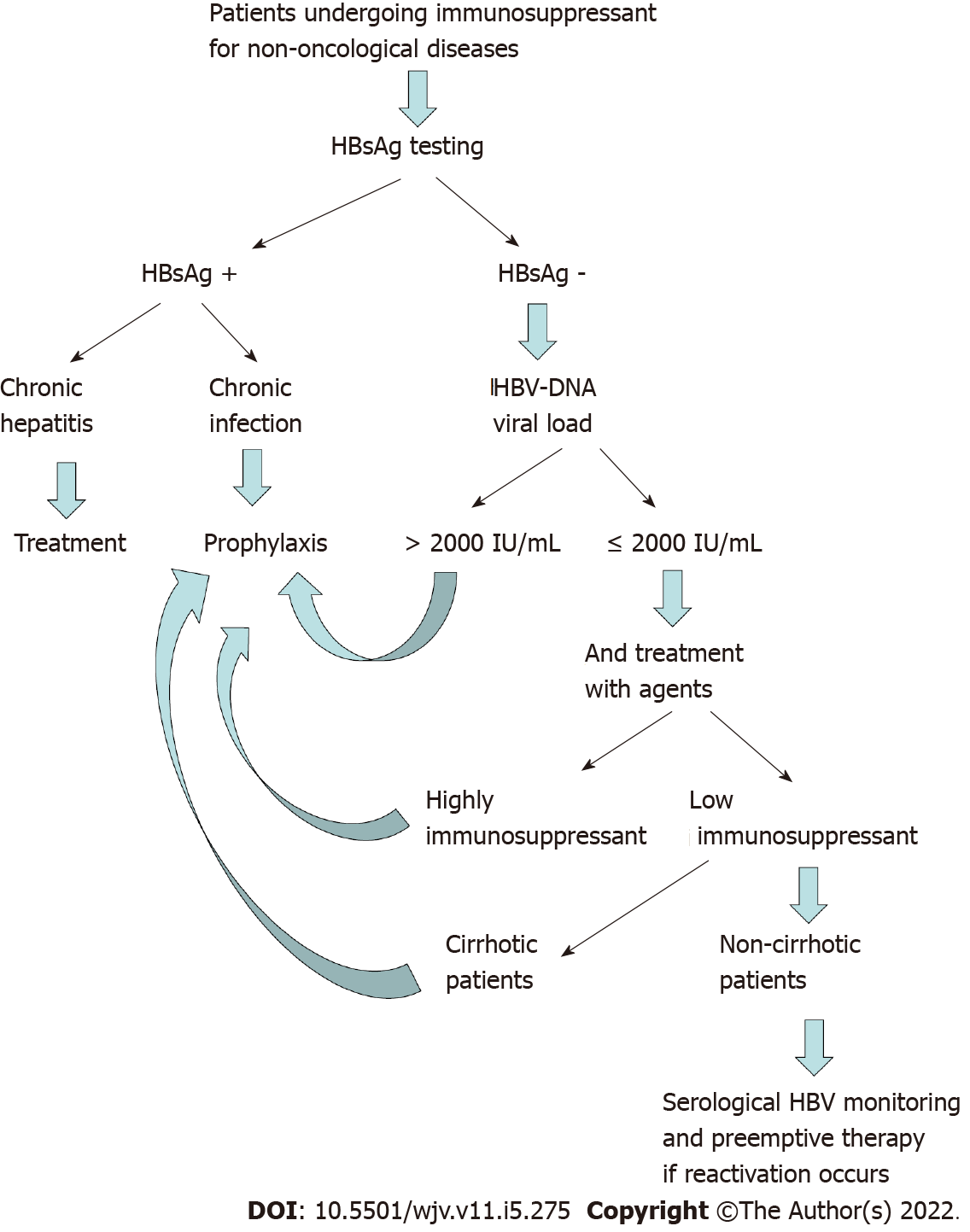

The risk of HBVr following immunosuppressive treatments depends mostly on type, duration and intensity of the iatrogenic immunosuppression. It is necessary to modulate any kind of therapeutic strategies to avoid HBVr, according to the risk profile of reactivation itself. Close monitoring of liver function test and qualitative/quantitative HBV DNA viral load is necessary at baseline, during and after the discontinuation of immunosuppressive therapy, taking into account that HBVr can still occur after the interruption of immunosuppressants. The management of HBVr in patients under immunosuppressant for non-oncological diseases depends, firstly, on HBsAg laboratory tests. In fact, in case of HBsAg positive value, patients with chronic hepatitis must undergo treatments of HBV with high genetic barrier nucleo(t)side analogues (entecavir, tenofovir, tenofovir alafenamide)[4,38,43-45], while those with chronic infection must be considered for prophylaxis with lamivudine in case of undetectable HBV DNA or in case of expected duration of prophylaxis less than 6 mo[38]. Otherwise, because of emergence of resistance to lamivudine in patients requiring therapy for more than 6 mo long duration, the above mentioned newer nucleoside agents can represent an effective option for antiviral prophylaxis in this setting. In case of HBsAg negative and HBcAb positive laboratory test results, the HBV DNA viral load can guide physicians in determining if the patient requires prophylaxis or clinical and laboratory’s close monitoring, followed, where appropriate, by preemptive therapy[4,38]. In fact, in case of HBV DNA positivity or in case of HBV DNA negativity occurred in patients under agents at moderate or high risk of immunosuppression, or affected by liver cirrhosis, a trimestral monitoring of HBsAg/HBsAb and HBV DNA is enough, and a preemptive therapy can be considered in case of reactivation[4,38]. The prophylaxis must be started before the immunosuppressive regimen and continued up to 12-18 mo after the end of the immunosuppressive treatment[38,46-48]. In Figure 1 briefly is summarized the algorithm of HBVr diagnosis and management in patients eligible for immunosuppressant in non-oncological setting.

The widespread use of immunosuppressive and immunomodulant therapies in non-oncological setting highlighted the risk of HBVr in patients with overt or occult hepatitis B virus infection. The occurrence of this challenging event can be reduced screening the population eligible for immunosuppressant to assess the best strategies according to any virological status. Further prospective studies are needed to increase data on the risk of HBVr related to newer immunomodulant agents employed in non-oncological setting, in order to better prevent and treat HBVr recurrence.

Dr Spera sincerely thanks Prof Grazia Tosone, MD for having taught her almost everything she knows about hepatitis B and for having passed on to her the love and passion for the study of infectious diseases.

| 1. | WHO|Guidelines for the Prevention, Care and Treatment of Persons with Chronic Hepatitis B Infection. (accessed on 16 March 2022). Available from: http://www.who.int/hepatitis/publications/hepatitis-b-guidelines/en/. |

| 2. | Raimondo G, Locarnini S, Pollicino T, Levrero M, Zoulim F, Lok AS; Taormina Workshop on Occult HBV Infection Faculty Members. Update of the statements on biology and clinical impact of occult hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2019;71:397-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 375] [Cited by in RCA: 400] [Article Influence: 57.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | van Houdt R, Bruisten SM, Speksnijder AG, Prins M. Unexpectedly high proportion of drug users and men having sex with men who develop chronic hepatitis B infection. J Hepatol. 2012;57:529-533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2017;67:370-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3745] [Cited by in RCA: 4015] [Article Influence: 446.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Ditto MC, Parisi S, Varisco V, Talotta R, Batticciotto A, Antivalle M, Gerardi MC, Agosti M, Borrelli R, Fusaro E, Sarzi-Puttini P. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection and risk of reactivation in rheumatic population undergoing biological therapy. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2021;39:546-554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mok CC. Hepatitis B and C infection in patients undergoing biologic and targeted therapies for rheumatic diseases. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2018;32:767-780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Perrillo RP, Gish R, Falck-Ytter YT. American Gastroenterological Association Institute technical review on prevention and treatment of hepatitis B virus reactivation during immunosuppressive drug therapy. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:221-244.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 352] [Cited by in RCA: 400] [Article Influence: 36.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 8. | Yeo W, Chan PK, Zhong S, Ho WM, Steinberg JL, Tam JS, Hui P, Leung NW, Zee B, Johnson PJ. Frequency of hepatitis B virus reactivation in cancer patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy: a prospective study of 626 patients with identification of risk factors. J Med Virol. 2000;62:299-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yeo W, Zee B, Zhong S, Chan PK, Wong WL, Ho WM, Lam KC, Johnson PJ. Comprehensive analysis of risk factors associating with Hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation in cancer patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:1306-1311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Wang B, Mufti G, Agarwal K. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus infection in patients with hematologic disorders. Haematologica. 2019;104:435-443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Seto WK, Chan TS, Hwang YY, Wong DK, Fung J, Liu KS, Gill H, Lam YF, Lie AK, Lai CL, Kwong YL, Yuen MF. Hepatitis B reactivation in patients with previous hepatitis B virus exposure undergoing rituximab-containing chemotherapy for lymphoma: a prospective study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3736-3743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 260] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pisaturo M, Di Caprio G, Calò F, Portunato F, Martini S, Coppola N. Management of HBV reactivation in non-oncological patients. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2018;16:611-624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Smalls DJ, Kiger RE, Norris LB, Bennett CL, Love BL. Hepatitis B Virus Reactivation: Risk Factors and Current Management Strategies. Pharmacotherapy. 2019;39:1190-1203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 14. | Mozessohn L, Chan KK, Feld JJ, Hicks LK. Hepatitis B reactivation in HBsAg-negative/HBcAb-positive patients receiving rituximab for lymphoma: a meta-analysis. J Viral Hepat. 2015;22:842-849. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Paul S, Saxena A, Terrin N, Viveiros K, Balk EM, Wong JB. Hepatitis B Virus Reactivation and Prophylaxis During Solid Tumor Chemotherapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:30-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Navarro R, Vilarrasa E, Herranz P, Puig L, Bordas X, Carrascosa JM, Taberner R, Ferrán M, García-Bustinduy M, Romero-Maté A, Pedragosa R, García-Diez A, Daudén E. Safety and effectiveness of ustekinumab and antitumour necrosis factor therapy in patients with psoriasis and chronic viral hepatitis B or C: a retrospective, multicentre study in a clinical setting. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:609-616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Orlandi EM, Elena C, Bono E. Risk of hepatitis B reactivation under treatment with tyrosine-kinase inhibitors for chronic myeloid leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2017;58:1764-1766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chen YM, Huang WN, Wu YD, Lin CT, Chen YH, Chen DY, Hsieh TY. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving tofacitinib: a real-world study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:780-782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Harigai M, Winthrop K, Takeuchi T, Hsieh TY, Chen YM, Smolen JS, Burmester G, Walls C, Wu WS, Dickson C, Liao R, Genovese MC. Evaluation of hepatitis B virus in clinical trials of baricitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. RMD Open. 2020;6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Liu J, Wang T, Cai Q, Sun L, Huang D, Zhou G, He Q, Wang FS, Liu L, Chen J. Longitudinal changes of liver function and hepatitis B reactivation in COVID-19 patients with pre-existing chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatol Res. 2020;50:1211-1221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Rodríguez-Tajes S, Miralpeix A, Costa J, López-Suñé E, Laguno M, Pocurull A, Lens S, Mariño Z, Forns X. Low risk of hepatitis B reactivation in patients with severe COVID-19 who receive immunosuppressive therapy. J Viral Hepat. 2021;28:89-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL Jr, Akl EA, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, Vaysbrot E, McNaughton C, Osani M, Shmerling RH, Curtis JR, Furst DE, Parks D, Kavanaugh A, O'Dell J, King C, Leong A, Matteson EL, Schousboe JT, Drevlow B, Ginsberg S, Grober J, St Clair EW, Tindall E, Miller AS, McAlindon T; American College of Rheumatology. 2015 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68:1-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 738] [Cited by in RCA: 794] [Article Influence: 72.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ramiro S, Smolen JS, Landewé R, van der Heijde D, Dougados M, Emery P, de Wit M, Cutolo M, Oliver S, Gossec L. Pharmacological treatment of psoriatic arthritis: a systematic literature review for the 2015 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:490-498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ho Lee Y, Gyu Song G. Comparative efficacy and safety of tofacitinib, baricitinib, upadacitinib, filgotinib and peficitinib as monotherapy for active rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2020;45:674-681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Canzoni M, Marignani M, Sorgi ML, Begini P, Biondo MI, Caporuscio S, Colonna V, Casa FD, Conigliaro P, Marrese C, Celletti E, Modesto I, Peragallo MS, Laganà B, Picchianti-Diamanti A, Rosa RD, Ferlito C, Salemi S, D'Amelio R, Stroffolini T. Prevalence of Hepatitis B Virus Markers in Patients with Autoimmune Inflammatory Rheumatic Diseases in Italy. Microorganisms. 2020;8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Terrault NA, Lok ASF, McMahon BJ, Chang KM, Hwang JP, Jonas MM, Brown RS Jr, Bzowej NH, Wong JB. Update on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidance. Hepatology. 2018;67:1560-1599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2290] [Cited by in RCA: 3102] [Article Influence: 387.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 27. | Lin TC, Hashemi N, Kim SC, Yang YK, Yoshida K, Tedeschi S, Desai R, Solomon DH. Practice Pattern of Hepatitis B Testing in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients: A Cross-National Comparison Between the US and Taiwan. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2018;70:30-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Fujita M, Sugiyama M, Sato Y, Nagashima K, Takahashi S, Mizokami M, Hata A. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: Analysis of the National Database of Japan. J Viral Hepat. 2018;25:1312-1320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Chen YL, Lin JZ, Mo YQ, Ma JD, Li QH, Wang XY, Yang ZH, Yan T, Zheng DH, Dai L. Deleterious role of hepatitis B virus infection in therapeutic response among patients with rheumatoid arthritis in a clinical practice setting: a case-control study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2018;20:81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Chiu HY, Chen CH, Wu MS, Cheng YP, Tsai TF. The safety profile of ustekinumab in the treatment of patients with psoriasis and concurrent hepatitis B or C. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1295-1303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ting SW, Chen YC, Huang YH. Risk of Hepatitis B Reactivation in Patients with Psoriasis on Ustekinumab. Clin Drug Investig. 2018;38:873-880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Loras C, Gisbert JP, Mínguez M, Merino O, Bujanda L, Saro C, Domenech E, Barrio J, Andreu M, Ordás I, Vida L, Bastida G, González-Huix F, Piqueras M, Ginard D, Calvet X, Gutiérrez A, Abad A, Torres M, Panés J, Chaparro M, Pascual I, Rodriguez-Carballeira M, Fernández-Bañares F, Viver JM, Esteve M; REPENTINA study; GETECCU (Grupo Español de Enfermedades de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa) Group. Liver dysfunction related to hepatitis B and C in patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with immunosuppressive therapy. Gut. 2010;59:1340-1346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 33. | Pérez-Alvarez R, Díaz-Lagares C, García-Hernández F, Lopez-Roses L, Brito-Zerón P, Pérez-de-Lis M, Retamozo S, Bové A, Bosch X, Sanchez-Tapias JM, Forns X, Ramos-Casals M; BIOGEAS Study Group. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation in patients receiving tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-targeted therapy: analysis of 257 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2011;90:359-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Clarke WT, Amin SS, Papamichael K, Feuerstein JD, Cheifetz AS. Patients with core antibody positive and surface antigen negative Hepatitis B (anti-HBc+, HBsAg-) on anti-TNF therapy have a low rate of reactivation. Clin Immunol. 2018;191:59-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Solay AH, Acar A, Eser F, Kuşcu F, Tütüncü EE, Kul G, Şentürk GÇ, Gürbüz Y. Reactivation rates in patients using biological agents, with resolved HBV infection or isolated anti-HBc IgG positivity. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2018;29:561-565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Pauly MP, Tucker LY, Szpakowski JL, Ready JB, Baer D, Hwang J, Lok AS. Incidence of Hepatitis B Virus Reactivation and Hepatotoxicity in Patients Receiving Long-term Treatment With Tumor Necrosis Factor Antagonists. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:1964-1973.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Papa A, Felice C, Marzo M, Andrisani G, Armuzzi A, Covino M, Mocci G, Pugliese D, De Vitis I, Gasbarrini A, Rapaccini GL, Guidi L. Prevalence and natural history of hepatitis B and C infections in a large population of IBD patients treated with anti-tumor necrosis factor-α agents. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:113-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Reddy KR, Beavers KL, Hammond SP, Lim JK, Falck-Ytter YT; American Gastroenterological Association Institute. American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on the prevention and treatment of hepatitis B virus reactivation during immunosuppressive drug therapy. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:215-9; quiz e16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 508] [Cited by in RCA: 466] [Article Influence: 42.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Rahier JF, Magro F, Abreu C, Armuzzi A, Ben-Horin S, Chowers Y, Cottone M, de Ridder L, Doherty G, Ehehalt R, Esteve M, Katsanos K, Lees CW, Macmahon E, Moreels T, Reinisch W, Tilg H, Tremblay L, Veereman-Wauters G, Viget N, Yazdanpanah Y, Eliakim R, Colombel JF; European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation (ECCO). Second European evidence-based consensus on the prevention, diagnosis and management of opportunistic infections in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:443-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 694] [Cited by in RCA: 762] [Article Influence: 63.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 40. | McGinley MP, Goldschmidt CH, Rae-Grant AD. Diagnosis and Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis: A Review. JAMA. 2021;325:765-779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 772] [Article Influence: 154.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Epstein DJ, Dunn J, Deresinski S. Infectious Complications of Multiple Sclerosis Therapies: Implications for Screening, Prophylaxis, and Management. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018;5:ofy174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Ciardi MR, Iannetta M, Zingaropoli MA, Salpini R, Aragri M, Annecca R, Pontecorvo S, Altieri M, Russo G, Svicher V, Mastroianni CM, Vullo V. Reactivation of Hepatitis B Virus With Immune-Escape Mutations After Ocrelizumab Treatment for Multiple Sclerosis. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6:ofy356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Brost S, Schnitzler P, Stremmel W, Eisenbach C. Entecavir as treatment for reactivation of hepatitis B in immunosuppressed patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:5447-5451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Chen FW, Coyle L, Jones BE, Pattullo V. Entecavir versus lamivudine for hepatitis B prophylaxis in patients with haematological disease. Liver Int. 2013;33:1203-1210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Koskinas JS, Deutsch M, Adamidi S, Skondra M, Tampaki M, Alexopoulou A, Manolakopoulos S, Pectasides D. The role of tenofovir in preventing and treating hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation in immunosuppressed patients. A real life experience from a tertiary center. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;25:768-771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Marrone A, Capoluongo N, D'Amore C, Pisaturo M, Esposito M, Guastafierro S, Siniscalchi I, Macera M, Boemio A, Onorato L, Rinaldi L, Minichini C, Adinolfi LE, Sagnelli E, Mastrullo L, Coppola N. Eighteen-month lamivudine prophylaxis on preventing occult hepatitis B virus infection reactivation in patients with haematological malignancies receiving immunosuppression therapy. J Viral Hepat. 2018;25:198-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Chew E, Thursky K, Seymour JF. Very late onset hepatitis-B virus reactivation following rituximab despite lamivudine prophylaxis: the need for continued vigilance. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55:938-939. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Dai MS, Chao TY, Kao WY, Shyu RY, Liu TM. Delayed hepatitis B virus reactivation after cessation of preemptive lamivudine in lymphoma patients treated with rituximab plus CHOP. Ann Hematol. 2004;83:769-774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Infectious diseases

Country/Territory of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cheng H, China; Zhu C, China S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH