Published online May 25, 2022. doi: 10.5501/wjv.v11.i3.150

Peer-review started: December 17, 2021

First decision: February 21, 2022

Revised: March 10, 2022

Accepted: April 22, 2022

Article in press: April 22, 2022

Published online: May 25, 2022

Processing time: 153 Days and 10.1 Hours

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic altered education, exams, and residency applications for United States medical students.

To determine the specific impact of the pandemic on US medical students and its correlation to their anxiety levels.

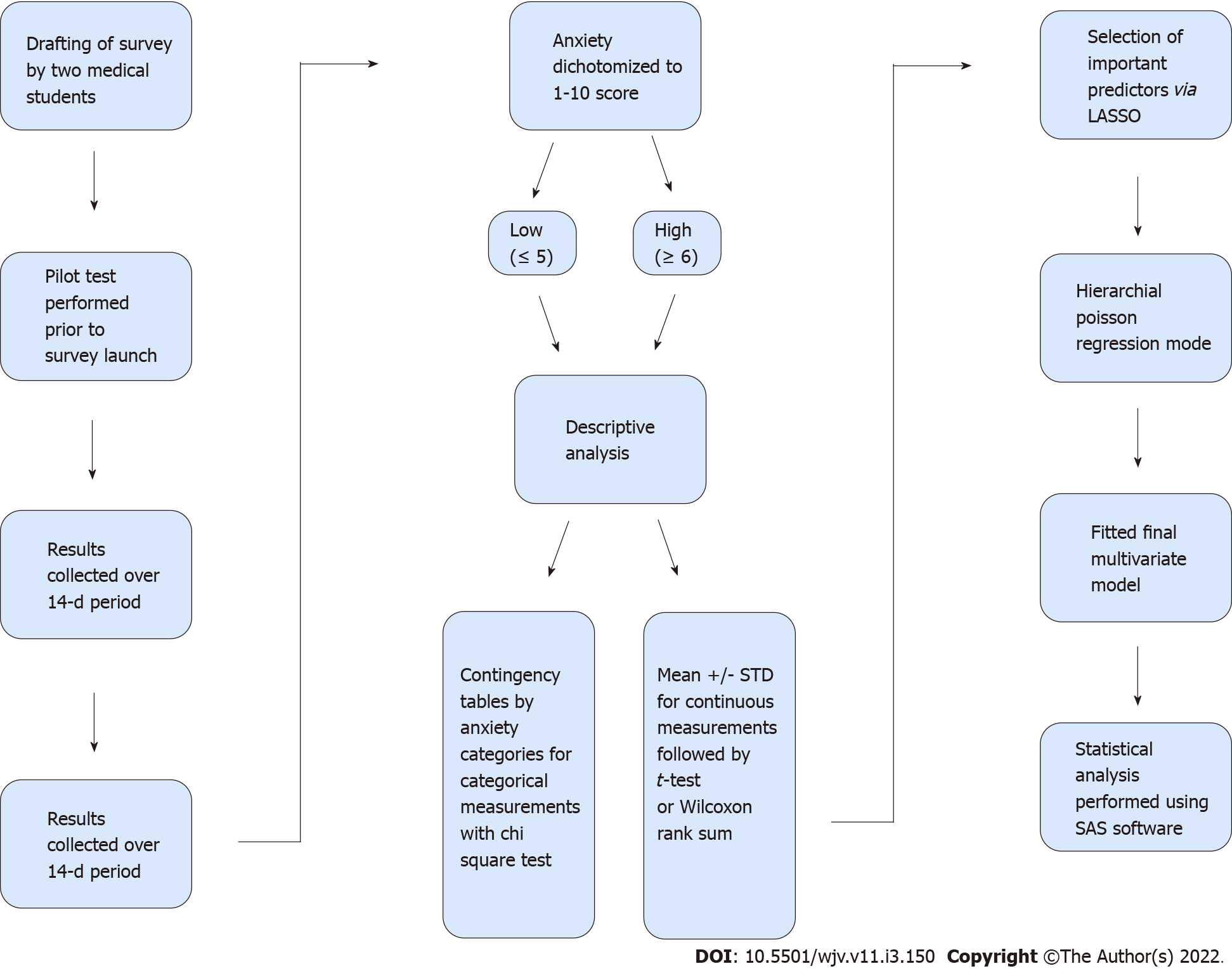

An 81-question survey was distributed via email, Facebook and social media groups using REDCapTM. To investigate risk factors associated with elevated anxiety level, we dichotomized the 1-10 anxiety score into low (≤ 5) and high (≥ 6). This cut point represents the 25th percentile. There were 90 (29%) shown as low anxiety and 219 (71%) as high anxiety. For descriptive analyses, we used contingency tables by anxiety categories for categorical measurements with chi square test, or mean ± STD for continuous measurements followed by t-test or Wilcoxson rank sum test depending on data normality. Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator was used to select important predictors for the final multivariate model. Hierarchical Poisson regression model was used to fit the final multivariate model by considering the nested data structure of students clustered within State.

397 medical students from 29 states were analyzed. Approximately half of respondents reported feeling depressed since the pandemic onset. 62% of participants rated 7 or higher out of 10 when asked about anxiety levels. Stressors correlated with higher anxiety scores included “concern about being unable to complete exams or rotations if contracting COVID-19” (RR 1.34; 95%CI: 1.05-1.72, P = 0.02) and the use of mental health services such as a “psychiatrist” (RR 1.18; 95%CI: 1.01-1.3, P = 0.04). However, those students living in cities that limited restaurant operations to exclusively takeout or delivery as the only measure of implementing social distancing (RR 0.64; 95%CI: 0.49-0.82, P < 0.01) and those who selected “does not apply” for financial assistance available if needed (RR 0.83; 95%CI: 0.66-0.98, P = 0.03) were less likely to have a high anxiety.

COVID-19 significantly impacted medical students in numerous ways. Medical student education and clinical readiness were reduced, and anxiety levels increased. It is vital that medical students receive support as they become physicians. Further research should be conducted on training medical students in telemedicine to better prepare students in the future for pandemic planning and virtual healthcare.

Core Tip: The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (coronavirus disease 2019) pandemic resulted in a significant impact on medical student education. Education was switched to on-line, examinations were changed, and students’ faced dismissal from hospital wards. In this study we analyzed the unique stressors that resulted in higher anxiety levels in medical students. From the results, we can agree that the development of medical school curricula for public health and mass casualty planning as well as providing further mental health support for medical students is necessary and should be further studied.

- Citation: Frank V, Doshi A, Demirjian NL, Fields BKK, Song C, Lei X, Reddy S, Desai B, Harvey DC, Cen S, Gholamrezanezhad A. Educational, psychosocial, and clinical impact of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic on medical students in the United States. World J Virol 2022; 11(3): 150-169

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3249/full/v11/i3/150.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5501/wjv.v11.i3.150

In March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) a worldwide pandemic. Starting in China, SARS-CoV-2 [coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)] went on to globally infect more than 426 million people and affect their community healthcare systems, calling on healthcare workers to work overtime to cover the exceeding demand for care[1]. American hospitals faced tremendous difficulty in not only providing enough hospital beds and ventilators for critically ill COVID-19 patients, but also in maintaining the care of existing critically ill patients recovering from a prolonged hospital course. Moreover, hospitals nationwide have faced a severe shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE) for front-line workers and healthcare workers in general[2]. These shortages with the necessity for slowing the rate of infection resulted in several isolation measures, including the temporary dismissal of many medical students from the hospital wards. Medical students amid their clinical training were placed in a particularly difficult spot; neither physicians, nurses, nor local public health departments were able to come to a consensus on whether or not medical students were to be considered “essential workers” amid the pandemic[3]. As a result, medical schools across the US varied in their placement of medical students during this time, either pulling medical students off the wards and away from progressing through their clinical training or fast-tracking their graduations to allow for additional assistance in hospitals and emergency departments with an overabundance of ill patients[4].

Classes were switched to online education to abide by local public health laws mandating stay-at-home orders. Students faced closures of their medical schools as well as postponements, cancellations, or changes to their National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) board and shelf exam[1] dates. In addition clinical rotation NBME shelf exams were switched from in-person proctored exams to online[5]. The United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step series of board exams continued to be administered at Prometric and other official testing centers, but with far fewer available spots, causing many students to go without any test date. To address this problem, the USMLE had designated specific medical schools as eligible testing centers for board exam administration in late May[5]. Additionally, there had been modifications to the residency application cycle, calling for the suspension of all in-person interviews in favor of virtual interviews. This presents significant challenges in allowing institutions and students to get to know each other on the only personal, in person, level that was possible for a typical residency application cycle[6].

Clearly, COVID-19 has had a significant impact on medical students, perhaps with lasting consequences that may affect their future careers. We aim to understand the extent to which COVID-19 has affected medical students by focusing on educational impact and clinical outcome with corresponding levels of anxiety. More specifically, our goal is to qualitatively evaluate the cancellation of academic activities, USMLE exam planning and preparation, or change of school year end date due to COVID-19 as well as psychological and financial impacts of the pandemic on the medical students. By knowing how global health crises affect future physicians, healthcare systems, national organizations and medical institutions can take steps to best prepare medical students while ensuring a stable trajectory towards training as well as healthy personal well-being and morale.

The online survey was designed to be anonymous to more accurately understand the impact of COVID-19 on medical students. A subset of questions were adapted from a survey studying the impact of COVID-19 on spine surgeons[7]. Only less than 30% of the questions were adopted from the survey on spine surgeons and the majority of questions were specifically designed for medical students. The questions went through several rounds of review and revision by the attendings of the medical school to verify they reliably assess the impact of COVID-19 on students. The Institutional Review Board of USC determined this study to be exempt from review (application number UP-20-00314).

A list of medical school contacts, including medical students and presidents from medical student associations, were compiled from 51 medical schools within the US through the students contributing to this survey. The survey was distributed using a secure web-based platform, REDCapTM (Research Electronic Data Capture), provided by our institution[8,9]. All invitations were sent via email or an online social networking platform with a short explanation of the study. Participants included medical students located in the United States in their pre-clinical, clinical, and research years. Participants were also encouraged to share the survey with their fellow medical students to expand the response rate. Due to the urgency of pandemic, we did not use any sampling strategy such as clustered sample or stratified sample. Instead, a broadcasting email went out to reach as many students as possible in a short period of time.

Two medical students drafted the survey questions, which were reviewed by a team that included medical students, research personnel, and physicians, and a pilot test was run prior to launch of the survey (Figure 1). A total of 81 questions were included in the survey with a 10-min estimated duration time. The survey analyzed the general demographics of participants including age, sex, medical school year, and the state in which medical school is located. The survey data included the following groupings on the impact of COVID-19: General impact, educational duties, medical school preparedness, exams and residency application impact, volunteering, working during the pandemic, financial, and psychological impact. For example, participants were asked about their local government restrictions, educational impact with closure of in-person medical schools, and how well their medical schools adapted. Further questions included changes made to exams, process of applying to residency changes, and levels of anxiety elicited by these changes and the uncertainty of the pandemic. The response options included: binary (yes/no), “non-applicable” and “I don’t know”; use of Likert scales on rating participants agreement on provided statements, and selection of items from a list also including text boxes for further elaboration.

The survey was distributed on May 6, 2020 via email and online social networking platforms using a secure web-based platform, REDCapTM. To protect the identity of the participants, no personal identifiers were saved such as IP address tracking, browser activities, read receipts, email activity, or similar data. Participants were encouraged to complete the survey on their own time and in a private environment. Results were collected over a 14-d period and the survey was closed on May 20, 2020. After the survey closure, the collected results were downloaded from REDCapTM and data analysis was initiated.

Mean age, response distribution percentage, Chi-squared test for categorical data, and independent t-tests for continuous measurements were used for descriptive analysis. To investigate risk factors associated with elevated anxiety level, we dichotomized the 1-10 anxiety score into low (≤ 5) and high (≥ 6). This cut point represents the 25th percentile of the original scale. We dichotomized items in order to maximize the number of cases and improve statistical power based on a recent study[10].

For descriptive analyses, we used contingency tables by anxiety categories for categorical measurements with chi square test, or mean ± STD for continuous measurements followed by t-test or Wilcoxon rank sum test depending on data normality. Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) was used to select important predictors for the final multivariate model[11]. Hierarchical Poisson regression model was used to fit the final multivariate model by considering the nested data structure of students clustered within State. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States).

397 medical students (61.17% women, overall participant mean age = 26 ± 2.43 years) who responded to the survey from 29 states were included in the analysis. The distribution across the United States is shown in Table 1, and the demographics of the respondents is demonstrated in Table 2. Of the respondents, 33% were in their first year, 22% second years, 25% third years, and 18% in their fourth year. The remaining 2% were either MD/PhD track students or in their research year. The results of the survey are presented below.

| State | N = 397 (%) |

| Missouri | 139 (35.0) |

| California | 68 (17.13) |

| Pennsylvania | 39 (9.82) |

| Massachusetts | 33 (8.31) |

| Washington | 28 (7.05) |

| Florida | 25 (6.3) |

| Texas | 17 (4.28) |

| Nebraska | 8 (2.02) |

| Illinois | 5 (1.26) |

| New York | 4 (1.01) |

| Wisconsin | 4 (1.01) |

| New Jersey | 3 (0.76) |

| Colorado | 3 (0.76) |

| Ohio | 3 (0.76) |

| Minnesota | 2 (0.50) |

| Alabama | 2 (0.50) |

| Nevada | 2 (0.50) |

| Michigan | 1 (0.25) |

| Arizona | 1 (0.25) |

| North Carolina | 1 (0.25) |

| Virginia | 1 (0.25) |

| Maine | 1 (0.25) |

| Georgia | 1 (0.25) |

| Washington DC | 1 (0.25) |

| Louisiana | 1 (0.25) |

| South Carolina | 1 (0.25) |

| North Dakota | 1 (0.25) |

| Kansas | 1 (0.25) |

| Idaho | 1 (0.25) |

The anxiety scale (1-10) had a distribution of 6.8 ± 2.4, with median of 7, Q1-Q3 of 5-9. When dichotomized by Q1, there were 90 (29%) shown as low anxiety and 219 (71%) as high anxiety.

When asked in the survey about medical students’ usual living situation during the school year, prior to the pandemic, 87% of participants selected “off-campus housing apartment-home” (Table 3). Approximately 39% of respondents noted a change in living situation due to the pandemic. Almost all participants (99%) selected “no” when asked if they currently feel sick with symptoms of COVID-19. The vast majority (95%) had not been tested for COVID-19. Notably, only 27% of respondents had a close relative or friend test positive for COVID-19. When asked to select all resources used to educate oneself about COVID-19 the top two were the World Health Organization (WHO)/the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (86%) and reading publications (76%). It was important to understand which resources medical students utilized to receive information and how these sources affected their anxiety level. Medical students who educated themselves with reliable resources, such as WHO/CDC and medical publications, exhibited a lower anxiety level compared to those who relied on information seen on social media. Furthermore, more than half of respondents (75%) did not know what personal protective equipment their medical school or center provided, while 15% noted “none.”

| General impact | Low anxiety, N = 90 (%) | High anxiety, N = 219 (%) | Total, N = 309 (%) | Sig. |

| Usual living situation during the school year (i.e. before the pandemic) | 0.97 | |||

| Home with family | 8 (30.77) | 18 (69.23) | 26 (8.41) | |

| Off-campus housing Apartment- House | 78 (28.89) | 192 (71.11) | 270 (87.38) | |

| Campus housing – School dormitory or apartment | 4 (30.77) | 9 (69.23) | 13 (4.21) | |

| Change in living situation during the pandemic | 0.04 | |||

| No | 63 (33.33) | 126 (66.67) | 189 (61.17) | |

| Yes | 27 (22.5) | 93 (77.5) | 120 (38.83) | |

| Currently living with | 0.54 | |||

| Alone | 13 (28.89) | 32 (71.11) | 45 (14.56) | |

| With spouse partner | 36 (34.29) | 69 (65.71) | 105 (33.98) | |

| With family | 27 (25.47) | 79 (74.53) | 106 (34.3) | |

| With roommates | 14 (29.17) | 34 (70.83) | 48 (15.53) | |

| Temporarily staying with friends or couch surfing | 0 (0) | 3 (100) | 3 (0.97) | |

| Other | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 2(0.65) | |

| I have easy access to testing for COVID-19 through my medical school/center if needed | 0.23 | |||

| 1 = Strongly disagree | 9 (21.95) | 32 (78.05) | 41 (13.27) | |

| 2 = Disagree | 18 (22.5) | 62 (77.5) | 80 (25.89) | |

| 3 = Neutral | 26 (31.71) | 56 (68.29) | 82 (26.54) | |

| 4 = Agree | 22 (31.88) | 47 (68.12) | 69 (22.33) | |

| 5 = Strongly agree | 15 (40.54) | 22 (59.46) | 37 (11.97) | |

| Do you currently feel sick with symptoms of COVID-19? | 0.36 | |||

| No | 90 (29.32) | 217 (70.68) | 307 (99.35) | |

| Yes | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 2 (0.65) | |

| Have you been tested for COVID-19 | 0.82 | |||

| No | 86 (29.35) | 207 (70.65) | 293 (95.13) | |

| Yes, awaiting test result | 1 (25) | 3 (75) | 4 (1.3) | |

| Yes, result was negative | 3 (33.33) | 6 (66.67) | 9 (2.92) | |

| Yes, result was positive | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 2 (0.65) | |

| Has a close relative or friend tested positive for COVID-19? | 0.2 | |||

| No | 70 (31.25) | 154 (68.75) | 224 (72.73) | |

| Yes | 20 (23.81) | 64 (76.19) | 84 (27.27) | |

| Resources used to educate about COVID-19-WHO CDC? | 0.67 | |||

| No | 14 (31.82) | 30 (68.18) | 44 (14.24) | |

| Yes | 76 (28.68) | 189 (71.32) | 265 (85.76) | |

| Resources used to educate about COVID-19-Reading publications? | 0.9 | |||

| No | 22 (29.73) | 52 (70.27) | 74 (23.95) | |

| Yes | 68 (28.94) | 167 (71.06) | 235 (76.05) | |

| Resources used to educate about COVID-19-Lectures educational resources from school? | 0.52 | |||

| No | 27 (76.73) | 74 (73.27) | 101 (32.69) | |

| Yes | 63 (30.29) | 145 (69.71) | 208 (67.31) | |

| Resources used to educate about COVID-19-Social media? | 0.17 | |||

| No | 40 (33.61) | 79 (66.39) | 119 (38.51) | |

| Yes | 50 (26.32) | 140 (73.68) | 190 (61.49) | |

| Medical school or center providing adequate access to PPE: Gowns | 0.27 | |||

| No | 81 (28.32) | 205 (71.68) | 286 (92.56) | |

| Yes | 9 (39.13) | 14 (60.87) | 23 (7.44) | |

| Medical school or center providing adequate access to PPE: Gloves | 0.35 | |||

| No | 81 (28.42) | 204 (71.58) | 285 (92.23) | |

| Yes | 9 (37.5) | 15 (62.5) | 24 (7.77) | |

| Medical school or center providing adequate access to PPE: Face shield or eye protection | 0.21 | |||

| No | 81 (28.22) | 206 (71.78) | 287 (92.88) | |

| Yes | 9 (40.91) | 13 (59.09) | 22 (7.12) | |

| Medical school or center providing adequate access to PPE: Surgical mask | 0.35 | |||

| No | 81 (28.42) | 204 (71.58) | 285 (92.23) | |

| Yes | 9 (37.5) | 15 (62.5) | 24 (7.77) | |

| Medical school or center providing adequate access to PPE: N95 or FF3 masks | 0.14 | |||

| No | 82 (28.18) | 209 (71.82) | 291 (94.17) | |

| Yes | 8 (44.44) | 10 (55.56) | 18 (5.83) | |

| Medical school or center providing adequate access to PPE: None | < 0.01 | |||

| No | 85 (32.2) | 179 (67.8) | 264 (85.44) | |

| Yes | 5 (11.11) | 40 (88.89) | 45 (14.56) | |

| Medical school or center providing adequate access to PPE: I do not know | 0.02 | |||

| No | 14 (18.42) | 62 (81.58) | 76 (24.6) | |

| Yes | 76 (32.62) | 157 (67.38) | 233 (75.4) |

When asked if their current academic activity (clinical rotations, in-person class, etc.) was cancelled and had not moved online, 73% of participants responded with “no” (Table 4). This implies that students who were removed from campuses and hospitals continued their medical education and training through online supplementation. 44% of participants also reported cancellation of their future academic activities. For those who answered “yes” to cancellation of academic activities, 33% noted a 2-6-mo cancellation, while 30% answered with “I am not sure.” Almost all participants (94%) had information being supplemented through distance or online learning. When asked how their overall workload was affected by the pandemic, more than half of the participants (54%) noted a decrease, while 14% had an increase in overall workload. 29% of participants also noted a decrease in research productivity. It is important to note that 45% of participants selected “does not apply,” meaning they were not involved in research.

| Educational impact | Low anxiety, N = 90 (%) | High anxiety, N = 219 (%) | Total, N = 309 (%) | Sig. |

| Was your current academic activity (for example clinical rotations, in-personal class, etc.) cancelled, and not moved online? | 0.29 | |||

| Yes | 20 (24.39) | 62 (75.61) | 82 (26.62) | |

| No | 69 (30.53) | 157 (69.47) | 226 (73.38) | |

| Were your future academic activities cancelled? | 0.02 | |||

| Yes | 31 (22.63) | 106 (77.37) | 137 (44.34) | |

| No | 59 (34.3) | 113 (65.7) | 172 (55.66) | |

| Is information being supplemented through distance/online learning? | < 0.01 | |||

| No | 0 (0) | 17 (100) | 17 (5.52) | |

| Yes | 89 (30.58) | 202 (69.42) | 291 (94.48) | |

| How has your overall workload been affected? | < 0.01 | |||

| Increased | 5 (11.36) | 39 (88.64) | 44 (14.24) | |

| Decreased | 60 (36.14) | 106 (63.86) | 166 (53.72) | |

| Unchanged | 25 (26.6) | 69 (73.4) | 94 (30.42) | |

| Does not apply | 0 (0) | 5 (100) | 5 (1.62) | |

| How has your research productivity been affected? | < 0.01 | |||

| Increased | 15 (38.46) | 24 (61.54) | 39 (12.62) | |

| Decreased | 23 (25.56) | 67 (74.44) | 90 (29.13) | |

| Unchanged | 20 (50) | 20 (50) | 40 (12.94) | |

| Does not apply | 32 (22.86) | 108 (77.14) | 140 (45.31) | |

| Has the school year end date been: | 0.04 | |||

| Cancelled | 1 (14.29) | 6 (85.71) | 7 (2.27) | |

| Postponed | 0 (0) | 8 (100) | 8 (2.59) | |

| Unchanged | 76 (30.89) | 170 (69.11) | 246 (79.61) | |

| Moved forward | 2 (16.67) | 10 (83.33) | 12 (3.88) | |

| Does not apply | 8 (53.33) | 7 (46.67) | 15 (4.85) | |

| I don’t know | 3 (14.29) | 18 (85.71) | 21 (6.8) | |

| Has graduation been: | 0.24 | |||

| Cancelled | 15 (23.08) | 50 (76.92) | 65 (21.1) | |

| Postponed | 3 (60) | 2 (40) | 5 (1.62) | |

| Unchanged | 44 (32.59) | 91 (67.41) | 135 (43.83) | |

| Moved forward | 0 (0) | 5 (100) | 5 (1.62) | |

| Does not apply | 21 (30.43) | 48 (69.57) | 69 (22.4) | |

| I don’t know | 7 (24.14) | 22 (75.86) | 29 (9.42) | |

| If applicable have your USMLE exams or equivalent state exams been postponed? | < 0.01 | |||

| Yes | 25 (19.84) | 101 (80.16) | 126 (40.78) | |

| No | 11 (36.67) | 19 (63.33) | 30 (9.71) | |

| Does not apply | 53 (38.41) | 85 (61.59) | 138 (44.66) | |

| Not sure | 1 (6.67) | 14 (93.33) | 15 (4.85) | |

| If the COVID-19 pandemic extends until or past August, I am concerned it will have a major effect on my continuing semesters or residency position | < 0.01 | |||

| 1 = Strongly disagree | 3 (100) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.97) | |

| 2 = Disagree | 12 (70.59) | 5 (29.41) | 17 (5.5) | |

| 3 = Neutral | 6 (26.09) | 17 (73.91) | 23 (7.44) | |

| 4 = Agree | 34 (41.98) | 47 (58.02) | 81 (26.21) | |

| 5 = Strongly agree | 27 (17.2) | 130 (82.8) | 157 (50.81) | |

| Does not apply | 8 (28.57) | 20 (71.43) | 28 (9.06) | |

| How effectively have your medical school leadership been managing this outbreak? | < 0.01 | |||

| Inadequate | 11 (13.58) | 70 (86.42) | 81 (26.47) | |

| Appropriate | 79 (36.07) | 140 (63.93) | 219 (71.57) | |

| Excessive | 0 (0) | 6 (100) | 6 (1.96) | |

| Which of the following best describes your medical school communication efforts to students? | < 0.01 | |||

| Overly frequent updates | 8 (33.33) | 16 (66.67) | 24 (7.79) | |

| Adequately frequent updates | 69 (35.38) | 126 (64.62) | 195 (63.31) | |

| Infrequent updates | 11 (14.47) | 65 (85.53) | 76 (24.68) | |

| No regular updates | 2 (15.38) | 11 (84.62) | 13 (4.22) |

Out of the respondents, 80% agreed there was no change in the school year end date and 54% also noted no change in school exam dates. 41% of participants who stated they were taking the USMLE exams noted a postponement in the exam dates. Medical students spend months preparing for the USMLE exams, a requirement for applying to residency, and any uncertainty regarding the exam can cause an increased anxiety level. Half of the participants (51%) strongly agreed to being concerned how the pandemic would affect their continuing semesters or residency positions, if it were to extend past August.

Respondents were asked using a Likert scale to rate their agreement with the statement “I am worried about the COVID-19 pandemic in general” (Table 5). 40% of participants strongly agreed and 43% agreed with the statement. Respondents were asked to rate their level of stress and anxiety using a scale from 1-10, with mean 6.7 ± 2.4 IQR (5, 8). The self-reported use of mental health resources compared to their previous experiences showed 59% remained unchanged, however there was an increase amongst some participants (17%). We asked to rate the accessibility to mental health services (psychologist, psychiatrist, 24-h emergency hotline, other) on a scale of 1 to 10. An average of 6.78 (SD = 2.33) was self-reported by the respondents. Half of the respondents (50%) reported experiencing an episode of depression during this time. The stressors which were most common amongst participants were waiting for campuses and clinical sites to reopen to students (51%), family well-being (46%), and personal well-being (41%). The self-care activities reported which were the most helpful to respondents were talking to friends (84%), television (81%), and exercise (77%).

| Psychosocial impact | Low anxiety, N = 90 (%) | High anxiety, N = 219 (%) | Total, N = 309 (%) | Sig. |

| I am worried about COVID-19 pandemic in general | < 0.01 | |||

| 1 = Strongly disagree | 3 (75) | 1 (25) | 4 (1.29) | |

| 2 = Disagree | 11 (68.75) | 5 (31.25) | 16 (5.18) | |

| 3 = Neutral | 15 (48.39) | 16 (51.61) | 31 (10.03) | |

| 4 = Agree | 46 (34.59) | 87 (65.41) | 133 (43.04) | |

| 5 = Strongly Agree | 15 (12) | 110 (88) | 125 (40.45) | |

| I am worried about contracting COVID-19 | < 0.01 | |||

| 1 = Strongly disagree | 11 (55) | 9 (45) | 20 (6.47) | |

| 2 = Disagree | 25 (39.06) | 39 (60.94) | 64 (20.71) | |

| 3 = Neutral | 31 (34.44) | 59 (65.56) | 90 (29.13) | |

| 4 = Agree | 21 (18.92) | 90 (81.08) | 111 (35.92) | |

| 5 = Strongly agree | 2 (8.33) | 22 (91.67) | 24 (7.77) | |

| If applicable, how has your utilization of mental health resources changed? | < 0.01 | |||

| Increased | 9 (17.31) | 43 (82.69) | 52 (16.83) | |

| Decreased | 2 (7.41) | 25 (92.59) | 27 (8.74) | |

| Unchanged | 59 (32.07) | 125 (67.93) | 184 (59.55) | |

| Does not apply | 20 (43.48) | 26 (56.52) | 46 (14.89) | |

| Mental health services the university provides: Psychologist | 0.29 | |||

| No | 31 (33.33) | 62 (66.67) | 93 (30.1) | |

| Yes | 59 (27.31) | 157 (72.69) | 216 (69.9) | |

| Mental health services the university provides: Psychiatrist | 0.84 | |||

| No | 59 (29.5) | 141 (70.5) | 200 (64.72) | |

| Yes | 31 (28.44) | 78 (71.56) | 109 (35.28) | |

| Mental health services the university provides: 24 hour emergency hotline | 0.7 | |||

| No | 41 (28.08) | 105 (71.92) | 146 (47.25) | |

| Yes | 49 (30.06) | 114 (69.94) | 163 (52.75) | |

| Mental health services the university provides: Does not apply | 0.02 | |||

| No | 73 (26.84) | 199 (73.16) | 272 (88.03) | |

| Yes | 17 (45.95) | 20 (54.05) | 37 (11.97) | |

| On a scale of 1-10, how accessible do you find mental health services? | 0.21 | |||

| 1 | 3 (33.33) | 6 (66.67) | 9 (2.95) | |

| 2 | 0 (0) | 5 (100) | 5 (1.64) | |

| 3 | 4 (21.05) | 15 (78.95) | 19 (6.23) | |

| 4 | 1 (11.11) | 8 (88.89) | 9 (2.95) | |

| 5 | 10 (19.23) | 42 (80.77) | 52 (17.05) | |

| 6 | 8 (25.81) | 23 (74.19) | 31 (10.16) | |

| 7 | 17 (32.08) | 36 (67.92) | 53 (17.38) | |

| 8 | 20 (36.36) | 35 (63.64) | 55 (18.03) | |

| 9 | 4 (19.05) | 17 (80.95) | 21 (6.89) | |

| 10 | 20 (39.22) | 31 (60.78) | 51 (16.72) | |

| Most Stress: Residency applications | 0.03 | |||

| No | 68 (33.01) | 138 (66.99) | 206 (66.67) | |

| Yes | 22 (21.36) | 81 (78.64) | 103 (33.33) | |

| Most Stress: Community well-being | 0.12 | |||

| No | 56 (26.42) | 156 (73.58) | 212 (68.61) | |

| Yes | 34 (35.05) | 63 (64.95) | 97 (31.39) | |

| Most Stress: Personal well-being | 0.31 | |||

| No | 57 (31.32) | 125 (68.68) | 182 (58.9) | |

| Yes | 33 (25.98) | 94 (74.02) | 127 (51.1) | |

| Most Stress: Family well-being | 0.08 | |||

| No | 56 (33.33) | 112 (66.67) | 168 (54.37) | |

| Yes | 34 (24.11) | 107 (75.89) | 141 (45.63) | |

| Most Stress: Clinical education related to COVID-19 | 0.05 | |||

| No | 70 (32.41) | 146 (67.59) | 216 (69.9) | |

| Yes | 20 (21.51) | 73 (78.49) | 93 (30.1) | |

| Most Stress: Limited to only essential activities | 0.04 | |||

| No | 47 (24.87) | 142 (75.13) | 189 (61.17) | |

| Yes | 43 (35.83) | 77 (64.17) | 120 (38.83) |

Hierarchical Poisson regression model showed students who experienced episodes of depression during this time was a strong risk of high anxiety level (RR 1.6; 95%CI: 1.38–1.85, P < 0.01). However, those participants who selected “Participated in volunteer activities for child care for health care workers” (RR 0.68; 95%CI: 0.49–0.93, P = 0.02); “USMLE exams or equivalent state exams NOT postponed” (RR 0.87; 95%CI: 0.76–0.99, P = 0.03); “Experienced support from school administration and faculty regarding COVID-19” (RR 0.75; 95%CI: 0.65–0.87, P < 0.01); and “Less concerned about being unable to complete exams or rotations if I contract COVID-19” (RR 0.77; 95%CI: 0.62–0.96, P = 0.02) were less likely having high anxiety (Table 6). Therefore, these would propose a protective effect on the level of anxiety experienced.

| Survey questions | Rate ratio | Confidence interval | Sig. |

| I feel disenchanted with the healthcare system due to inadequate response, lack of PPE, lack of testing, etc. | |||

| Disagree (2) vs Strongly disagree (1) | 0.93 | 0.5-1.72 | 0.81 |

| Neutral (3) vs Strongly disagree (1) | 1.39 | 0.85-2.27 | 0.19 |

| Agree (4) vs Strongly disagree (1) | 1.48 | 0.95-2.31 | 0.09 |

| Strongly agree (5) vs Strongly disagree(1) | 1.39 | 0.86-2.25 | 0.18 |

| Does not apply vs Strongly disagree (1) | 0.93 | 0.5-1.72 | 0.81 |

| Volunteer Activities - Child care for health care workers: Yes vs No | 0.68 | 0.49-0.93 | 0.02 |

| Is the distance learning beneficial to you? | |||

| Agree vs Strongly agree | 0.87 | 0.6-1.27 | 0.47 |

| Neutral vs Strongly agree | 0.93 | 0.62-1.37 | 0.7 |

| Disagree vs Strongly agree | 0.98 | 0.66-1.46 | 0.93 |

| Strongly disagree vs Strongly agree | 0.84 | 0.57-1.23 | 0.36 |

| If applicable, have your USMLE exams or equivalent state exams been postponed? | |||

| No vs Yes | 0.87 | 0.76-0.99 | 0.03 |

| Does not apply vs Yes | 1.01 | 0.87-1.18 | 0.85 |

| Not sure vs Yes | 1.19 | 0.96-1.48 | 0.12 |

| How concerned are you that COVID-19 will affect the residency application process? | |||

| Slightly concerned (2) vs Not concerned (1) | 1.3 | 0.79-2.13 | 0.3 |

| Moderately concerned (3) vs Not concerned (1) | 1.22 | 0.79-1.88 | 0.36 |

| Very concerned (4) vs Not concerned (1) | 0.86 | 0.58-1.26 | 0.43 |

| Extremely concerned (5) vs Not concerned (1) | 1 | 0.6-1.68 | 1 |

| Does not apply vs Not concerned (1) | 1.3 | 0.79-2.13 | 0.3 |

| On a scale of 1-5 how supportive have school administration and faculty been regarding COVID-19? | |||

| 2 vs Not supportive | 0.81 | 0.63-1.04 | 0.1 |

| Moderately supportive vs Not supportive | 0.75 | 0.65-0.87 | < 0.011 |

| 4 vs Not supportive | 0.79 | 0.6-1.03 | 0.09 |

| Extremely supportive vs Not supportive | 0.89 | 0.78-1.02 | 0.11 |

| Have you experienced episodes of depression during this time? | 1.6 | 1.38-1.85 | < 0.011 |

| I am concerned about being unable to complete exams or rotations if I contract COVID-19 | |||

| Strongly disagree (1) vs Strongly agree (5) | 0.66 | 0.26-1.7 | 0.39 |

| Disagree (2) vs Strongly agree (5) | 0.77 | 0.62-0.96 | 0.02 |

| Neutral (3) vs Strongly agree (5) | 1.11 | 0.95-1.3 | 0.2 |

| Agree (4) vs Strongly agree (5) | 1.05 | 0.84-1.31 | 0.68 |

| Does not apply vs Strongly agree (5) | 0.88 | 0.69-1.14 | 0.34 |

Respondents were asked to rate their level of agreement with the statement “COVID-19 has increased the community perception of physicians and healthcare workers as heroes” (Table 7). 23% strongly agreed with the statement and 19% were neutral regarding it. Most of the respondents (96%) were not assisting in the healthcare system at the time of the survey due to restraints caused by COVID-19. Respondents were asked to rate their level of preparedness working with COVID-19 patients on a scale of 1-5. It was important to know if medical students felt ready to care for patients, especially if they were required to volunteer. A lack of preparedness can further increase the anxiety and stress level medical students may already be experiencing. Approximately 45% felt not prepared at all, while 32% gave a rating of 2. When asked if they have the option to volunteer in the hospital for COVID-19, many students responded with no (78%). Out of the respondents, 49% would like to volunteer, however a portion were unable to volunteer due to external factors. The greatest external factor were respondents living or helping with family and/or friends and they did not want to risk exposure. It should be noted that medical students in their pre-clinical years are more likely to feel less prepared to volunteer in the hospital, compared to those students in their clinical and post-graduate years who have more experience on the hospital wards.

| Clinical, future, and financial impact | Low anxiety, N = 90 (%) | High anxiety, N = 219 (%) | Total, N = 309 (%) | Sig. |

| COVID-19 has increased the community perception of physicians and healthcare workers | 0.1 | |||

| 1 = Strongly disagree | 1 (25) | 3 (75) | 4 (1.29) | |

| 2 = Disagree | 7 (26.92) | 19 (73.08) | 26 (8.41) | |

| 3 = Neutral | 11 (18.64) | 48 (81.36) | 59 (19.09) | |

| 4 = Agree | 44 (30.14) | 102 (69.86) | 146 (47.25) | |

| 5 = Strongly agree | 25 (34.72) | 47 (65.28) | 72 (23.3) | |

| Does not apply | 2 (100) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.65) | |

| Are you required to assist in the healthcare system currently due to COVID-19? | 0.06 | |||

| Yes I am being put to work wherever I a needed | 0 (0) | 3 (100) | 3 (0.97) | |

| Yes I am continuing to work in the same clinical role that I was in pre-pandemic | 0 (0) | 10 (100) | 10 (3.24) | |

| No | 90 (30.41) | 206 (69.59) | 296 (95.79) | |

| Do you have the option to volunteer to work in the hospital for COVID-19? | 0.31 | |||

| No | 66 (27.5) | 174 (72.5) | 240 (77.92) | |

| Yes | 23 (33.82) | 45 (66.18) | 68 (22.08) | |

| Would you like to volunteer? | 0.34 | |||

| Yes | 46 (30.26) | 106 (69.74) | 152 (49.35) | |

| No | 28 (32.94) | 57 (67.06) | 85 (27.6) | |

| Cannot due to external factors | 16 (22.54) | 55 (77.46) | 71 (23.05) | |

| Cannot volunteer due to external factors: I live or help out with family and or friends who I do not want to risk exposure | 0.1 | |||

| No | 81 (30.92) | 181 (69.08) | 262 (84.79) | |

| Yes | 9 (19.15) | 38 (80.85) | 47 (15.21) | |

| Cannot volunteer due to external factors: I am concerned about my own safety | 0.56 | |||

| No | 88 (29.63) | 209 (70.37) | 297 (96.12) | |

| Yes | 2 (16.67) | 10 (83.33) | 12 (3.88) | |

| Cannot volunteer due to external factors: I have to work elsewhere for financial reasons | 0.11 | |||

| No | 90 (29.7) | 213 (70.3) | 303 (98.06) | |

| Yes | 0 (0) | 6 (100) | 6 (1.94) | |

| Volunteer activities: Fundraising or obtaining PPE for hospitals | 0.52 | |||

| No | 81 (29.89) | 190 (70.11) | 271 (87.7) | |

| Yes | 3 (21.43) | 29 (76.32) | 38 (12.3) | |

| Volunteer Activities: Helping answer COVID-19 phone lines | 0.41 | |||

| No | 84 (29.79) | 198 (70.21) | 282 (91.26) | |

| Yes | 6 (22.22) | 21 (77.78) | 27 (8.74) | |

| Volunteer Activities: Child care for healthcare workers | 0.02 | |||

| No | 78 (27.37) | 207 (72.63) | 285 (92.33) | |

| Yes | 12 (50) | 12 (50) | 24 (7.77) | |

| On a scale of 1-5, how prepared to you feel to work with COVID-19 patients? | 0.38 | |||

| 1 = Not at all prepared | 37 (72.79) | 99 (72.79) | 136 (44.16) | |

| 2 | 26 (26.26) | 73 (73.74) | 99 (32.14) | |

| 3 = Adequately prepared | 14 (42.42) | 19 (57.58) | 33 (10.71) | |

| 4 | 5 (27.78) | 13 (72.22) | 18 (5.84) | |

| 5 = Extremely well prepared | 0 (0) | 3 (100) | 3 (0.97) | |

| Does not apply | 7 (36.84) | 12 (63.16) | 19 (6.17) | |

| On a scale of 1-5, how prepared to you feel to work in the general healthcare system (caring for internal medicine patients, surgical patients, etc.)? | 0.5 | |||

| 1 = Not at all prepared | 17 (34) | 33 (66) | 50 (16.18) | |

| 2 | 25 (28.74) | 62 (71.26) | 87 (28.16) | |

| 3 = Adequately prepared | 23 (25.27) | 68 (74.73) | 91 (29.46) | |

| 4 | 17 (33.33) | 34 (66.67) | 51 (16.5) | |

| 5 = Extremely well prepared | 2 (13.33) | 13 (86.67) | 15 (4.85) | |

| Does not apply | 6 (40) | 9 (60) | 15 (4.85) |

When presented with the statement “has the pandemic affected you financially,” participants were asked to respond in a Likert scale format (Table 8) in which 21% agreed with the statement. Financial assistance availability was present for 34% of respondents, and 41% did not know if any was present. When asked which available emergency funds were accessible the highest response rate (19.2%) was through the school financial aid office.

| Financial impact | Low anxiety, N = 90 (%) | High anxiety, N = 219 (%) | Total, N = 309 (%) | Sig. |

| Has the pandemic affected you financially? | < 0.01 | |||

| Strongly Agree | 1 (5.56) | 17 (94.44) | 18 (5.83) | |

| Agree | 13 (20.31) | 51 (79.69) | 64 (20.71) | |

| Neutral | 25 (22.73) | 85 (77.27) | 110 (35.6) | |

| Disagree | 36 (39.56) | 55 (60.44) | 91 (29.45) | |

| Is financial assistance available to you if needed? | 0.3 | |||

| Yes | 37 (35.24) | 68 (64.76) | 105 (33.98) | |

| No | 10 (20.83) | 38 (79.17) | 48 (15.53) | |

| I do not know | 35 (27.34) | 93 (72.66) | 128 (41.42) | |

| Does not apply | 8 (28.57) | 20 (71.43) | 28 (9.06) |

The anticipation of having similar outbreaks in the future was presented with a Likert scale and respondents were asked to rate the statement in which 51% agreed with the statement (Table 9). Respondents were asked to rate on a scale of 1-5 their fear of how future public health crises will be handled. 48% of participants agreed, and 22% strongly agreed, that the lessons learned from this outbreak will help us cope with future crises. The need for medical school curricula in local mass casualty planning was addressed in a Likert scale, in which 50% of respondents agreed and 22% strongly agreed with the statement.

| Future impact | Low anxiety, N = 90 (%) | High anxiety, N = 219 (%) | Total, N = 309 (%) | Sig. |

| I anticipate having similar outbreaks in the future | 0.35 | |||

| 1 = Strongly disagree | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.32) | |

| 2 = Disagree | 6 (46.15) | 7 (53.85) | 13 (4.22) | |

| 3 = Neutral | 11 (31.43) | 24 (68.57) | 35 (11.36) | |

| 4 = Agree | 46 (29.3) | 111 (70.7) | 157 (50.97) | |

| 5 = Strongly agree | 25 (25) | 75 (75) | 100 (32.47) | |

| Does not apply | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 2 (0.65) | |

| I am fearful of how future public health crises will be handled? | < 0.01 | |||

| 1 = Strongly disagree | 2 (100) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.65) | |

| 2 = Disagree | 15 (65.22) | 8 (34.78) | 23 (7.52) | |

| 3 = Neutral | 16 (43.24) | 21 (56.76) | 37 (12.09) | |

| 4 = Agree | 31 (24.8) | 94 (75.2) | 125 (40.85) | |

| 5 = Strongly agree | 25 (21.19) | 93 (78.81) | 118 (38.56) | |

| Does not apply | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.33) | |

| I think the lessons we learn from this outbreak will help us cope with future crises? | 0.04 | |||

| 1 = Strongly disagree | 3 (37.5) | 5 (62.5) | 8 (2.59) | |

| 2 = Disagree | 11 (34.38) | 21 (65.63) | 32 (10.36) | |

| 3 = Neutral | 9 (17.65) | 42 (82.35) | 51 (16.5) | |

| 4 = Agree | 38 (25.68) | 110 (74.32) | 148 (47.9) | |

| 5 = Strongly agree | 28 (40.58) | 41 (59.42) | 69 (22.33) | |

| Does not apply | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.32) | |

| I think we need medical school curricula in national mass casualty planning? | 0.13 | |||

| 1 = Strongly disagree | 0 (0) | 4 (100) | 4 (1.3) | |

| 2 = Disagree | 7 (41.18) | 10 (58.82) | 17 (5.52) | |

| 3 = Neutral | 22 (28.21) | 56 (71.79) | 78 (25.32) | |

| 4 = Agree | 49 (33.56) | 97 (66.44) | 146 (47.4) | |

| 5 = Strongly agree | 11 (17.74) | 51 (82.26) | 62 (20.13) | |

| Does not apply | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 1 (0.32) |

Currently, there is minimal literature on medical students experiencing a pandemic and how a public health crisis may affect medical education. In our study, we have used a 1-10 scale to quality anxiety level, then dichotomized base one Q1 value of 5 into “At least some anxiety (≥ 6) “ or “low to no anxiety (≤ 5)”. By treating the anxiety measurements as a continuous scale, it is more likely to dilute important information. The difference between a scoring of 1 vs 3, 4 vs 6, or 7 vs 9 is the same, however a scoring of 1 and 3 or 7 and 9 will belong to the same level of anxiety. Dichotomizing a continuous anxiety/stress scale has been used in literature. In most cases, studies would like to detect high risk populations who had higher anxiety/stress level and the risk factors associated with the elevated anxiety level. The benefit of dichotomizing includes providing more clinical meaningful result and better statistical power compared to the modeling approach using outcome with multiple categories[12,13].

Our study was designed to rapidly respond to a worldwide pandemic. To maintain data accuracy, we used the QC procedure to examine any missing data. 19.6% of our survey results were returned with some missing data. Among those, only four participants with more than four missing items were found, from a total of 308 survey questions. The sensitivity analysis was conducted with and without the missing data. The findings between the two data sets were consistent. Therefore, we have concluded that this minimal amount of missing data did not influence our findings from the study.

From our study, we have found that COVID-19 has significantly impacted medical students across the United States. 54.87% of respondents were first- and second-year medical students and 43.18% were third-year medical students, most of whom were suddenly disrupted during the peak of their clinical education. Regardless of their progress through medical school, nearly all students have faced abrupt changes in medical education and clinical training, resulting in concern and uncertainty with regard to their paths towards residency programs. Most students noted restrictions in their cities, including medical school closure, shelter or safer-at-home measures, social distancing, limited restaurant operations, and mandates to keep only essential businesses open. The majority of respondents reported that their current academic activities had been cancelled and moved online to a distance learning curriculum, predominantly via Zoom, and approximately half felt it was not beneficial to them. Of these respondents, decreased motivation with online learning and an inadequate quality of virtual curriculum were cited as the biggest issues. Due to the unforeseen nature of the pandemic, schools were not prepared to teach medical students remotely. This consequentially resulted in decreased medical student workloads. Restrictions from going on campus and to corresponding medical centers may have contributed to a decrease in students’ research productivity as well.

Of those facing postponements in their USMLE or equivalent state exams, almost half of respondents felt very or extremely concerned about the impact of COVID-19 on the residency application process. With this year’s residency application deadline looming at the end of October 2020, it is worrisome for students to consider submitting an incomplete application to a system that is already extremely competitive. In an effort to reduce unnecessary exposure and further viral spread, virtual residency interviews will be held for the 2021 Match. It is expected to cause many difficulties in the application process and perhaps negatively impact the applicant even further. It is anticipated that applicants will accept more interviews because of the reduced cost and time needed to travel to each institution, adding to the already growing hyperinflation in the application process. With these changes, programs will ultimately spend less money and time on each applicant. This begs the question if there will be an increase in the number of interview invites. Medical students may anticipate saving money with these adjustments as well, thus being more likely to apply to an increased number of residency programs. While this may seem like a positive result of the pandemic, with more competitive medical students overapplying, less competitive students may consequentially have more difficulty securing a virtual interview. To avoid this issue, a fifteen-interview limit per applicant, per specialty, could allow below-average applicants an equal opportunity, but there is no guarantee that AAMC will implement such a regulation[6].

Less than half of medical student respondents indicated wanting to volunteer during the pandemic, perhaps because none reported previous or current infection. Based on survey respondent comments, many based this on their attempt to preserve their own health and the health of family members and friends. Additionally, this finding may emphasize that medical students feel vastly ill-prepared to work in a pandemic environment. It is difficult for medical students to feel prepared and secure if they do not see this reflected in their own institution. A majority of students did not have adequate or any access to PPE gowns, N-95 or FF3 masks during this time. In light of the lack of preparative measures to protect healthcare workers, and by extension medical students, in a pandemic or public health crisis, it is no surprise that more than half of respondents believe their medical school should offer curricula in national mass casualty planning[14]. In order for medical schools to be prepared for future public health crises, we now know that measures must be in place to allow for the continuation of quality medical school education regardless of outbreak or mass casualty status. In addition to the evident need for better PPE preparation across the US, a preparation that should include all students working in a clinical setting, there is concern over how the COVID-19 pandemic, and possible future public health crises, will affect medical students’ ability to work clinically and prevent early burnout. Based on our results, medical students already feel disenchanted with the US healthcare system with an overarching sense of worry for the current state of affairs and what is to come with future health crises. In a career path previously touted as stable, nothing seems predictable now. Almost half of respondents have been most stressed by their inability to go to campus or clinical sites. These destinations are not only a source of education for students, but also a source of community. As our data shows, this disruption has caused a predictable increase in anxiety. The additional stress of being limited to essential activities and worrying about residency applications also does not bode well for mental health outcomes in these future physicians. This crisis has exacerbated existing medical student mental health issues in addition to instilling fear for the future, which an overwhelming majority of respondents indicated experiencing.

Clearly, medical students and residency program applications care about hands-on education. However, given the current situation, an effort to teach future physicians how to practice non-traditionally is needed, which may include telemedicine and tele-education. Recent research into remote and virtual medical education may prove to be a solution for future needs. Some studies have even shown virtual reality to be a useful tool for both learning motivation and learning competency in medical students[15]. With the AAMC recommendation to remove students from the wards to conserve PPE, new modalities of clinical education have already been put into place, such as remote grand rounds via Zoom, virtual reality cadaver dissections, and case discussions through online curriculum platforms such as Aquifer[16]. We recommend more research into these methods, as well as medical student exposure to participating in clinical care via telemedicine. These changes, understandably, bring feelings of uncertainty and instability to not only educators, but also medical students. In addition to the changes brought about by the pandemic, medical students face uncertainty with what to expect this school year and perhaps beyond graduation. We found that 74.6% feel concerned about the pandemic affecting continuing semesters or their residency position were the pandemic to extend past August 2020. 55.6% indicated concern over being unable to complete rotations and/or exams were they to be infected with COVID-19. Medical students make an immense investment by committing to medical school, both financially and mentally, and many cite the job’s stability and satisfaction as primary factors for choosing to go into medicine in the first place. It is understandable that lacking the clear path towards a career so often cited as a stable and predictable journey has stirred up discomfort for the entire medical community. For medical students in particular, anxiety had already been on the rise, and now further exacerbated by the pandemic[17].

We conducted our multivariate analysis to specifically look at the effect of these educational and clinical changes on the anxiety of medical students. The level of anxiety of the participant, or lack of, may impact the response rate to those survey questions dealing with anxiety. It is not uncommon to have a high percentage of “no response” rate. The missing data is not necessarily problematic in every instance. Participants may not report on one variable because of the anxiety exhibited from it or because of it. For example, a study which examined the tobacco use of adolescent smokers who smoked heavily found that the number of cigarettes smoked per day was not reported. It is assumed that due to the illegality of smoking for these individuals, many participants may have experienced fear of reper-cussions, thus limiting their response rate[18]. This concept seen in adolescent smokers can provide a valuable explanation on the “no response” rate seen on those questions using anxiety as its variable in this study. Thus, we grouped non-respondents and high-level of anxiety respondents vs low-level of anxiety respondents in the multivariate analysis, which looked at educational impact and clinical outcome as the main variables causing an effect on anxiety.

Uncertainty has been one of the main drivers of anxiety among medical students. We found that those who were unsure whether their USMLE or equivalent state exams would be postponed were more likely to have a higher level of anxiety. Those who primarily used the WHO and CDC websites as a source of their education regarding COVID-19 were less likely to have high levels of anxiety. Those who reported experiencing episodes of depression during this time were more likely to have high levels of anxiety. Those who indicated being worried about contracting COVID-19 were more likely to have high levels of anxiety as well. Medical schools have made attempts to better wellness programs for their students and to make mental health resources more available, and perhaps the accessibility of these resources is indeed reaching students in need. We found that those who selected or knew their school offered a psychiatrist were more likely to have high levels of anxiety. We can interpret that because of their anxiety, they have contemplated seeking or have sought the aid of a psychiatrist, and thus were knowledgeable about their school having this resource available.

The need for mental health resource accessibility for medical students remains clear; approximately 33% of medical students worldwide have anxiety, a significantly greater prevalence than the general population[19]. This anxiety does not stop after medical school graduation. The anxiety, stress, and susceptibility to depression continues throughout residency and into attending life if help-seeking behaviors are not encouraged early on in the work environment[20]. Availability of mental health resources for medical students has a lasting effect, helping future physicians develop healthy stress-reducing habits early on in their careers. Adequate mental health should not only be a concern for physicians-in-training and physicians, but also for patients. Studies have found that physicians are less likely to make medical errors when less stressed[20]. Now more than ever, there need to be adequate mental health programs in place. The pandemic has only further exacerbated psychosocial issues that were already problems for student doctors and physicians[21]. Undeniably, the best way to improve health outcomes and patient care is to support our doctors and doctors-in training, and this includes doctors supporting each other. Without this, we risk a devastating mental health crisis that would affect all[21].

There is minimal information regarding the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical students. The study of Harries et al[22] shows that more than two third of medical students believe the pandemic has significantly disrupted their education. More than half of the students expressed desire to return to their normal clinical rotations, accepting the risk of infection with COVID-19. In another study by Alsoufi et al[23] more than 85% of the participating medical students reported suspended educational programs, lectures, and clinical rotations during the pandemic. However, the reported studies suffer from significant limitations, such as limited survey response rate (although the students were directly contacted from their medical school leadership), and therefore, further studies in this field were recommended.

Perhaps this surreal time in our lives has indicated we need to conduct medical education differently. The pandemic has revealed the flaws in medical education when curriculum is devoted entirely or predominantly towards in-person learning. We need to incorporate nontraditional learning into medical education. This may include educating and preparing medical students for practicing in nontraditional ways, such as via telemedicine. We have found that clinic visits can be conducted successfully over a remote interface, posing the question if follow-up in-person visits are actually essential to quality medical care. In fact, the pandemic has highlighted much of what is truly essential in healthcare, and a closer look at what has been emphasized and successfully conducted during this time can guide medical school curriculum committees on where to emphasize their medical education efforts.

There are several limitations to this study. The sample population was largely composed of medical students with access to social media, neglecting those who may limit their social media presence. Furthermore, survey responses were dependent upon the point in time in which respondents filled out the survey, as responses would surely vary at different times during the pandemic. Most of the studied subjects were from California, Florida, Massachusetts, Missouri, Pennsylvania, and Washington. However, we may say that those six states with the highest participants are from West, Central, and East of the USA, which somehow can represent a sample of the entire nation’s students. These states are also very popular to receive students from other states, which again helps in generalizability of the results to the entire country. Additionally, our survey may not ask all pertinent questions assessing the holistic impact of COVID-19 on medical students. The majority of students participating in the survey were in their beginning four years of their studies. This highlights an additional limitation as the final two years are the clinical training years and students faced dismissal from the hospital wards. Lastly, our survey was voluntary, potentially biasing our results to respondents who may have felt strongly about sharing their experiences. Although our study has some limitations, it focuses on some aspects of the medical student education, such as preparation and planning for USMLE exams and school year end date, that have not been assessed in the published reports. More importantly, respondent distribution across the United States in our study is geographically different from the limited available reports, which is another important advantage of our study. Given the fact that the geographic distribution of COVID-19 is not uniform, its psychosocial effects on the population is also not homogeneous. More specifically, different medical schools have implemented different strategies to respond to the pandemic, which certainly result in different effects on their medical students. As research on the impact of pandemics on medical students is limited, adding to the pool of these reports and data could positively improve our understanding about how pandemics affect medical schools, which areas of educational programs are more vulnerable, and which supporting strategies are important to employ to subdue the effects of pandemics effectively and safely on the education.

This study provides insight and important information about how medical students have experienced and been affected by the pandemic. Ultimately, we found that medical students have been significantly impacted in numerous ways. From our results, we now know that amid a public health crisis, medical student education and clinical readiness were reduced, with predictably negative outcomes on medical student anxiety and presumably, residency applications. As no prior research has been done on the effect of a global pandemic on medical students and medical education, we recommend that efforts be placed in healthcare system readiness for public health crises[24], the development of medical school curricula for public health and mass casualty planning, and further mental health support that starts with changing physician culture and stigma and encouraging mental health resource utilization. Furthermore, we encourage research on medical student education that is focused on what has been found to be critically essential. This includes training students in telemedicine and virtual care where applicable. We hope that the results of this study will initiate a restructuring of medical education that will consider medical students’ experiences and the potential consequences of future challenges as well as training in non-traditional ways.

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic prompted abrupt closures of medical schools affecting education, exams, and residency applications for United States medical students.

The survey was drafted by two medical students who faced on-campus closure's of their medical schools and the uncertainty of it's impact on medical education. We wanted to determine potential outcomes caused by the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on medical students and examine what measures should be taken in the future to better prepare students for pandemics.

The aim of the study was to determine what specific factors impacted medical students, their anxiety, and the effect on medical education. It is important to examine these factors and determine what can be done in the future to prevent similar outcomes.

The survey was drafted by two medical students, revised by multiple attending physicians, and a pilot test was performed prior to the survey launch. Anxiety scores were dichotomized to a 1-10 score and for descriptive analysis contingency tables by anxiety categories for categorical measurements and mean ± STD for continuous measurements followed by t-test or Wilcoxson rank were performed. Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator was utilized to select important predictors for the final multivariate model. The final model was fitted by Hierarchical Poisson regression model.

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic greatly impacted medical students' anxiety levels. There was a strong educational and clinical impact and students were faced with many uncertainties, driving up their anxiety levels. It has become evident the need for mental health resource accessibility for medical students is crucial. We still need to better understand the long term effects the pandemic will have on these students as they transition into becoming doctors and how medical schools can better prepare students for future pandemics or global health crises.

This study provides insight on important information about how medical students have experienced and been affected by the pandemic. We recommend that efforts be placed in the healthcare system readiness for public health crisis, the development of medical school curricular for public health and mass casualty planning, along with further mental health support. We encourage research on medical education that is focused on what has been found to be critically essential: training students in tele-medicine and virtual care.

Further research should be focused on the long-term effects of the pandemic on medical students, especially as they transition into residency. Research should also be conducted on training students in virtual care and preparedness for future public health crises.

| 1. | Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). World Health Organization 2020. (accessed February 23, 2022). Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019. |

| 2. | Ranney ML, Griffeth V, Jha AK. Critical Supply Shortages - The Need for Ventilators and Personal Protective Equipment during the Covid-19 Pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:e41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1276] [Cited by in RCA: 1202] [Article Influence: 200.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Whelan A, Prescott J, Young G, Catanese VM, McKinney R. Guidance on Medical Students’ Participation in Direct Patient Contact Activities. AAMC 2020. (accessed May 28, 2020). Available from: www.aamc.org/system/files/2020-04/meded-April-14-Guidance-on-Medical-Students-Participation-in-Direct-Patient-Contact-Activities.pdf. |

| 4. | Thousands of medical students are being fast-tracked into doctors to help fight the coronavirus. CNN 2020. (accessed June 12, 2020). https://edition.cnn.com/2020/03/19/europe/medical-students-coronavirus-intl/index.html. |

| 5. | United States Medical Licensing Examination | Announcements 2020. (accessed June 8, 2020). Available from: https://www.usmle.org/announcements/. |

| 6. | Rajesh A, Asaad M. Alternative Strategies for Evaluating General Surgery Residency Applicants and an Interview Limit for MATCH 2021: An Impending Necessity. Ann Surg. 2021;273:109-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Louie PK, Harada GK, McCarthy MH, Germscheid N, Cheung JPY, Neva MH, El-Sharkawi M, Valacco M, Sciubba DM, Chutkan NB, An HS, Samartzis D. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Spine Surgeons Worldwide. Global Spine J. 2020;10:534-552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O'Neal L, McLeod L, Delacqua G, Delacqua F, Kirby J, Duda SN; REDCap Consortium. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5422] [Cited by in RCA: 17215] [Article Influence: 2459.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38562] [Cited by in RCA: 40343] [Article Influence: 2373.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Drachev SN, Brenn T, Trovik TA. Prevalence of and factors associated with dental anxiety among medical and dental students of the Northern State Medical University, Arkhangelsk, North-West Russia. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2018;77:1454786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Frank E HJ. Regression Modeling Strategies with Applications to Linear Models, Logistic Regression, and Survival Analysis. 2015. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kim SY, Shin YC, Oh KS, Shin DW, Lim WJ, Kim EJ, Cho SJ, Jeon SW. The association of occupational stress and sleep duration with anxiety symptoms among healthy employees: A cohort study. Stress Health. 2020;36:675-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Stockbridge EL, Wilson FA, Pagán JA. Psychological distress and emergency department utilization in the United States: evidence from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21:510-519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Myers L, Balakrishnan S, Reddy S, Gholamrezanezhad A. Coronavirus Outbreak: Is Radiology Ready? J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17:724-729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sattar MU, Palaniappan S, Lokman A, Hassan A, Shah N, Riaz Z. Effects of Virtual Reality training on medical students' learning motivation and competency. Pak J Med Sci. 2019;35:852-857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Weiner S. No classrooms, no clinics: Medical education during a pandemic. AAMC 2020. (accessed May 30, 2020). Available from: https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/no-classrooms-no-clinics-medical-education-during-pandemic. |

| 17. | Gallagher TH, Schleyer AM. "We Signed Up for This! N Engl J Med. 2020;382:e96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 28.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Little TD, Jorgensen TD, Lang KM, Moore EW. On the joys of missing data. J Pediatr Psychol. 2014;39:151-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 337] [Cited by in RCA: 387] [Article Influence: 29.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Quek TT, Tam WW, Tran BX, Zhang M, Zhang Z, Ho CS, Ho RC. The Global Prevalence of Anxiety Among Medical Students: A Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in RCA: 454] [Article Influence: 64.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Nielsen KJ, Pedersen AH, Rasmussen K, Pape L, Mikkelsen KL. Work-related stressors and occurrence of adverse events in an ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31:504-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bowman J, MD, L A, ry, June 11 M| C|, 2020. We need improved mental health care for physicians. KevinMDCom 2020. (accessed June 20, 2020). Available from: https://www.kevinmd.com/blog/2020/06/we-need-improved-mental-health-care-for-physicians.html. |

| 22. | Harries AJ, Lee C, Jones L, Rodriguez RM, Davis JA, Boysen-Osborn M, Kashima KJ, Krane NK, Rae G, Kman N, Langsfeld JM, Juarez M. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical students: a multicenter quantitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21:14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 31.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Alsoufi A, Alsuyihili A, Msherghi A, Elhadi A, Atiyah H, Ashini A, Ashwieb A, Ghula M, Ben Hasan H, Abudabuos S, Alameen H, Abokhdhir T, Anaiba M, Nagib T, Shuwayyah A, Benothman R, Arrefae G, Alkhwayildi A, Alhadi A, Zaid A, Elhadi M. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical education: Medical students' knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding electronic learning. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0242905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 360] [Cited by in RCA: 334] [Article Influence: 55.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Demirjian NL, Fields BKK, Song C, Reddy S, Desai B, Cen SY, Salehi S, Gholamrezanezhad A. Impacts of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on healthcare workers: A nationwide survey of United States radiologists. Clin Imaging. 2020;68:218-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Virology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Khosravi M, Iran; Liu XQ, China; Mohammadi S, Iran S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH